- Review Article

- Abstract

- The Concept of Ideology in Economics

- Sustainability as an Ideological Challenge

- Reconsidering Economics

- A Conceptual Framework for Sustainability

- Positional Analysis – A Democracy-Oriented Approach

- Decision Making in Multiple Steps

- Accounting for Sustainability

- Complexity and the Roles of Analyst and Decision Maker

- Concluding Comments

- References

Economics for Democracy and Sustainability

Peter Söderbaum*

School of Economics, Society and Technology, Mälardalen University, Västerås, Sweden

Submission: December 09, 2023; Published: December 13, 2023

*Corresponding author: Peter Söderbaum, School of Economics, Society and Technology, Mälardalen University, Västerås, Sweden

How to cite this article: Peter Söderbaum*. Economics for Democracy and Sustainability. Acad J Politics and Public Admin. 2024; 1(1): 555551. DOI:10.19080/ACJPP.2024.01.555551.

- Review Article

- Abstract

- The Concept of Ideology in Economics

- Sustainability as an Ideological Challenge

- Reconsidering Economics

- A Conceptual Framework for Sustainability

- Positional Analysis – A Democracy-Oriented Approach

- Decision Making in Multiple Steps

- Accounting for Sustainability

- Complexity and the Roles of Analyst and Decision Maker

- Concluding Comments

- References

Abstract

Present political economic systems nationally and globally are largely made legitimate by mainstream neoclassical economics with its emphasis on GDP-growth and monetary profits in business. But development has been, and still is, unsustainable in important respects, environmental degradation being among examples. Governance for sustainability can certainly be discussed within the scope of mainstream economics. The failure or limitations of neoclassical theory and method suggests however that also heterodox approaches to economics deserve attention. In this paper a version of ecological economics, i.e., economics for sustainability, is presented. Economics is defined in a new way with emphasis on multidimensional management of resources and democracy. Individuals and organizations are regarded as political economic actors guided by their ideological orientation or mission. As an alternative to neoclassical Cost-Benefit Analysis (CBA), Positional Analysis is advocated. The latter approach seriously considers irreversibility of negative impacts on future living conditions and takes democracy seriously.

Keywords: Political Economics; Democracy; Ideological Orientation; Sustainability; Neoclassical CBA; Positional Analysis; Accounting; Inertia; Irreversibility; Resilience; Complexity

Abbreviations: CBA: Cost-Benefit Analysis; GDP: Gross Domestic Product; CSR: Corporate Social Responsibility; PEO: Political-Economic Organization; PEP: Political-Economic Person; SDGs: Sustainable Development Goals

- Review Article

- Abstract

- The Concept of Ideology in Economics

- Sustainability as an Ideological Challenge

- Reconsidering Economics

- A Conceptual Framework for Sustainability

- Positional Analysis – A Democracy-Oriented Approach

- Decision Making in Multiple Steps

- Accounting for Sustainability

- Complexity and the Roles of Analyst and Decision Maker

- Concluding Comments

- References

The Concept of Ideology in Economics

In a democracy there are mansy voices to be listened to and considered. In other words, there are actors with different “ideological orientations” who deserve attention before making decisions. Economists do not often use words such as “ideology” or “ideological orientation”. In a mainstream neoclassical textbook, “ideology” as well as “democracy” are absent from Glossary and Index Mankiw and Taylor [1]. Ideology is perhaps considered as being part of some other discipline, such as political science. Economists also often claim expertise in the sense of value-neutrality, implying that ideology and similar concepts are not relevant for economic theory and method. But there are exceptions to this main trend of avoiding “ideology” as a term and concept in economics.

i. In her early book “Economic Philosophy”, Joan Robinson argues that economics “has always been a vehicle for the ruling ideology of each period”. She explains the word ideology as follows: We must go round to find the roots of our own beliefs. In the general mass of notions and sentiments that make up an ideology those concerned with economic life play a large part, and economics itself (that is the subject as it is taught in universities and evening classes and pronounced upon in leading articles) has always been partly a vehicle for the ruling ideology of each period as well as partly a method of scientific investigation Robinson [2].

ii. In the early 1990s Douglass North defined ideology as follows: By ideology I mean the subjective perceptions (models, theories) all people possess to explain the world around them. Whether at the microlevel of individual relationships or at the macrolevel of organized ideologies providing integrated explanations of the past and present, such as communism or religions, the theories individuals construct is colored by normative views of how the world should be organized North [3].

iii. Tomas Piketty is an economist who departs from the mainstream by making “ideology” an important part of his writings. In the book “Capital and Ideology” (2020), he describes his use of ideology as follows: I use ideology in a positive and constructive sense to refer to a set of a priori plausible ideas and discourses describing how society should be structured. An ideology has social, economic, and political dimensions. It is an attempt to respond to a broad set of questions concerning the desirable or ideal organization of society. Given the complexity of the issues, it should be obvious that no ideology can ever commend full and total assent: ideological conflict and disagreement are inherent in the very notion of ideology. Nevertheless, every society must attempt to answer questions about how it should be organized, usually based on its own historical experience but sometimes also on the experiences of other societies. Individuals will also usually feel called on to form opinions of their own on these fundamental existential issues, however vague or unsatisfactory they may be.

iv. I agree with this view that “ideology” is necessarily present in economics research and education and “ideological orientation” is added as clarification. Ideology and ideological orientation can seldom be expressed in simplistic mathematical terms but are still useful in guiding behavior. Gunnar Myrdal instead refers to “values” and “valuation” in his writings arguing that “values are always with us” as economists: Valuations are always with us. Disinterested research there has ever been and can never be. Prior to answers there must be questions. There can be no view except from a viewpoint. In the questions raised and the viewpoint chosen, valuations are implied Myrdal [4].

According to this view, economics is always “political economics” and ideas about value neutrality must be downplayed or abandoned. If economics is political economics, then democracy needs to be part of the discipline. At issue is how economists and economics can contribute to a strengthened democracy. To deal with this question a new conceptual framework appears to be needed. The idea is however not to replace neoclassical economics in “paradigm-shift” terms as suggested by Thomas Kuhn [5]. Instead, an “Institutional Ecological Economics” is proposed as part of a pluralist “paradigm-coexistence” perspective. Neoclassical theory and methods are still useful since this perspective is today dominant among many actor categories in business and public administration. Mainstream economics is also relevant for purposes of comparison when a theoretical perspective that claims some newness is presented.

- Review Article

- Abstract

- The Concept of Ideology in Economics

- Sustainability as an Ideological Challenge

- Reconsidering Economics

- A Conceptual Framework for Sustainability

- Positional Analysis – A Democracy-Oriented Approach

- Decision Making in Multiple Steps

- Accounting for Sustainability

- Complexity and the Roles of Analyst and Decision Maker

- Concluding Comments

- References

Sustainability as an Ideological Challenge

Mainstream neoclassical theory and method offers certain ways of understanding business corporations, consumers, markets, and the whole economy. A conceptual framework is presented where a firm is assumed to maximize monetary profits, a consumer maximizes utility (subject to a budget constraint). At the level of society, Cost-Benefit Analysis (CBA) tells us how to maximize “present value” in monetary terms, and how market transactions in the national economy can be aggregated to a Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Economic growth in GDP-terms has become the main indicator of welfare for politicians and other actors.

The examples suggest that there is a preference for quantitative analysis, if possible, in one-dimensional monetary terms. The analysis aims at “optimal” solutions for the firm, the consumer and for society through CBA. Optimal solutions imply one-dimensional analysis according to a specific ideological orientation, excluding other possibilities. Something is achieved in this way, but something is also lost through far-reaching simplification. The focus on the monetary dimension can be described as “monetary reductionism”. Instead, a more holistic approach considering some elements of complexity is needed. Mainstream neoclassical economics has been in a monopoly position at university departments of economics in a period when development has become increasingly unsustainable. Climate change, loss of biodiversity, pollution of land, air and water are signs of degradation which is irreversible or not easily reversed. The recent COVID-pandemic adds to the picture and strengthens the arguments for new and broader perspectives. In 2015 the United Nations sanctioned no less than 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) with sub-targets and “The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development” [6]. This agenda can be regarded as a move away from focus on one-dimensional economic growth in GDP-terms to a multidimensional analysis, economic growth being just one of the 17 SDGs (Number 8).

- Review Article

- Abstract

- The Concept of Ideology in Economics

- Sustainability as an Ideological Challenge

- Reconsidering Economics

- A Conceptual Framework for Sustainability

- Positional Analysis – A Democracy-Oriented Approach

- Decision Making in Multiple Steps

- Accounting for Sustainability

- Complexity and the Roles of Analyst and Decision Maker

- Concluding Comments

- References

Reconsidering Economics

In neoclassical textbooks, “economics” relates to decisionmaking and defined as “allocation of scarce resources”. This definition will here be modified or changed in two respects. A first elaboration is that reference is made to “multidimensional” management of limited resources. A second clarification is that analysis is carried out in a “democratic society”. This is a way of bringing the political dimension into analysis with “ideological orientation” as a key concept. Economics or rather “political economics” is then defined as: “Economics is multidimensional management of limited resources in a democratic society” Söderbaum [7,8]. Why “multidimensional” management and why reference to a democratic society? Neoclassical theory and method are essentially one-dimensional in monetary terms. The focus is on markets and actual or hypothetical prices. In CBA applied to investment projects, this is a way to identify the best or “optimal” alternative. At the level of the firm monetary profits are similarly what counts. This neoclassical monetary analysis is specific not only in scientific terms but also with respect to ideological orientation. In a democratic society many different ideological orientations are represented, and economists have no right to dictate one ideological orientation as correct. Additional and competing ideological orientations are often relevant. While neoclassical economics focuses on economic growth in GDP-terms and profits in business, the mentioned 17 SDGs with Agenda 2030, sanctioned by the United Nations, represent a different ideological orientation. And additional ideological orientations can certainly be relevant in areas such as transportation, energy systems etcetera. This suggests that an issue should be illuminated in relation to different ideological orientations judged relevant. Conclusions about the order of preference of alternatives will then be conditional in relation to each ideological orientation considered. This is a way of bringing conflicts between ideological orientations seriously into the decision process. Ideology becomes part of analysis rather than being something left to politicians or other decision makers. As previously argued neoclassical economics with its CBA is an attempt to dictate a specific ideological orientation while downplaying other ideological orientations and democracy. This economics is accepted not only in democracies but also in nations such as Russia and China with their close to dictatorships. A democracy-oriented economics then becomes a contribution, albeit limited to the global power game between political regimes.

Decision-making is regarded as a “matching” process between each actor’s ideological orientation and the expected multidimensional impact profile of each alternative considered. Rather than “matching”, reference can be made to “appropriateness”, “compatibility” and even “pattern recognition”. In the latter case, the ideological orientation is thought of as a desirable pattern to be related to the expected impact profile in multidimensional terms of each alternative as another pattern. Ideological orientation as well as impact profile are normally fragmentary and uncertain but may still be useful in guiding behavior. The strategy in neoclassical CBA is to deal with all kinds of impacts by transforming them into a common denominator, money. Existing market prices are then the starting point. But why these prices and why exclude other ethical and ideological concerns? Some actors may point to “intrinsic values” for example of specific species being threatened. Other non-monetary impacts, such as CO2 emissions, are similarly irreversible. A “correct price” may then by some actors be regarded as infinite. It is therefore recommended that non-monetary impacts are understood and described in their own terms as part of a profile of impacts. Each actor as decision maker will then refer to her ideological orientation and values about the relative importance of different impacts.

- Review Article

- Abstract

- The Concept of Ideology in Economics

- Sustainability as an Ideological Challenge

- Reconsidering Economics

- A Conceptual Framework for Sustainability

- Positional Analysis – A Democracy-Oriented Approach

- Decision Making in Multiple Steps

- Accounting for Sustainability

- Complexity and the Roles of Analyst and Decision Maker

- Concluding Comments

- References

A Conceptual Framework for Sustainability

In their ideas of successful science, neoclassical economists tend to point to physics and other natural sciences. Individuals and firms are looked upon as mechanistic entities connected by markets. The roles of an individual are limited to consumer and worker while firms are producers of commodities and purchasers of labor. Individuals as well as firms can be influenced by government measures, for example taxes and prohibitions. As part of the present political-economics perspective, individuals and organizations are certainly interrelated through markets but they are actors in a broader sense. It is assumed that an individual is a political-economic person (PEP) and actor, guided by her ideological orientation, and potentially responsible for her behavior in the economy. This responsibility refers both to a role as citizen and to market behavior. A political-economic organization (PEO) is similarly an actor, guided by its ideological orientation or “mission”. This mission can be limited to market performance in terms of monetary profits but can alternatively be broader in scope. For business companies, Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and “Fair Trade” become relevant issues. The actor’s perspective is relevant also for markets. “No Business is an Island” Håkansson & Snehota [9]. An actor within a company is part of networks that often extend beyond the company and the actor may bother about other actors in a supply-chain, or other actors more generally.

Organizations are not limited to firms in the neoclassical sense but include public organizations, for example universities and Civil Society Organizations of a not-for-profit kind, such as Greenpeace Bode [10]. Those in charge of governmental policy may regard individuals and organizations as physical entities and may design measures accordingly with taxes or shut-down policies, or they may focus more upon attitudes and engagement of individuals as actors. Governments play a central role in policymaking but all actors in the economy can be understood as “policymakers” with ideas about common and separate interests. Looking upon individuals and organizations as actors suggests that actors within the national government can encourage other actors to cooperate in the implementation of governmental policy. Policy in relation to COVID-19 then becomes a choice between combinations of shut-down measures and attempts to involve and encourage individuals and organizations to participate. In the case of Sweden, COVID policies have included significant activities of involvement (with public press conferences sent regularly in television) in addition to shut-down measures. Whether this policy has been successful or not is an open issue. Personally, I believe that policies should be based on an ideological orientation where “involvement” (rather than shut-down measures) plays the primary role.

- Review Article

- Abstract

- The Concept of Ideology in Economics

- Sustainability as an Ideological Challenge

- Reconsidering Economics

- A Conceptual Framework for Sustainability

- Positional Analysis – A Democracy-Oriented Approach

- Decision Making in Multiple Steps

- Accounting for Sustainability

- Complexity and the Roles of Analyst and Decision Maker

- Concluding Comments

- References

Positional Analysis – A Democracy-Oriented Approach

How should decisions concerning infrastructure projects be prepared in a democratic society? The answer by a neoclassical economist is Cost-Benefit Analysis (CBA). But CBA represents a specific ideology, which is close to economic growth ideology. Limiting attention to the ideology built into CBA – while disregarding all other ethical and ideological orientations – can hardly be seen as compatible with democracy. Emphasis on the CBA ideological orientation is rather a case of manipulation. When compared with CBA, Positional Analysis (PA) is an approach that claims to be more compatible with a strengthened democracy Söderbaum, Brown et al., Söderbaum [11-13]. Rather than looking for an optimal solution as in CBA, the aim is to “illuminate” an issue in a many-sided way with respect to:

i. Ideological orientations supported by stakeholders or otherwise judged relevant.

ii. Kindls of alternatives of choice.

iii. Expected multidimensional impact profiles of each alternative.

Many-sidedness is a way of avoiding or at least reducing manipulation. More than one ideological orientation should be considered, and the ideological orientations should be relevant in relation to decision makers and those concerned. They should also differ from each other and can reflect conflict of interest. Alternatives of choice may similarly differ in kind and scales and impact profiles are of a multidimensional kind. The impacts of alternatives are of four kinds:

i. Monetary flows

ii. Monetary positions

iii. Non-monetary flows

iv. Non-monetary positions

CBA is an analysis in terms of monetary flows. Positional Analysis considers and does not exclude monetary flows and positions but emphasizes non-monetary impacts, particularly non-monetary positions. While flows refer to periods of time, positions (or stocks or states) refer to points in time. Our interest in sustainability suggests that we should focus on avoiding degradation of ecosystems, natural resources, and health in positional terms. CBA is a monetary trade-off philosophy where all kinds of impacts can be traded against each other. Positional Analysis on the other hand points to the possibility of inertia and irreversibility in many non-monetary dimensions, suggesting that the CBA trade-off philosophy is seriously misleading.

- Review Article

- Abstract

- The Concept of Ideology in Economics

- Sustainability as an Ideological Challenge

- Reconsidering Economics

- A Conceptual Framework for Sustainability

- Positional Analysis – A Democracy-Oriented Approach

- Decision Making in Multiple Steps

- Accounting for Sustainability

- Complexity and the Roles of Analyst and Decision Maker

- Concluding Comments

- References

Decision Making in Multiple Steps

If inertia and irreversibility are present, then it is often wise to think of decisions as changes of positions in multiple stages Söderbaum [7]. In a game of chess, each player normally thinks in stages beyond the first move. Each move opens the door for specific future moves and at the same time forecloses other moves and possibilities. Uncertainty is present concerning the moves of the opponent and success is a matter of foresight, of strategies considering future possibilities. In a democracy we expect politicians or other decision makers to know what they are doing when advocating one alternative of choice before another and when making their decisions by voting, for example. The role of the analyst is to inform decision makers and other actors as well as possible about the impacts of each alternative and how alternatives relate to identified ideological orientations. Irreversibility or difficulties to reverse a change in position is an issue in relation to many dimensions of sustainability, for example CO2 pollution from transportation, exploitation of natural resources through mining activities, pollution of water systems and land-use changes. In the latter case construction of houses or roads on agricultural land can for practical purposes be regarded as irreversible. Returning to agricultural land is not easily done. When ecosystems are concerned, reference can be made to resilience. An ecosystem that is disturbed may later return to something similar (or equal) to the position before disturbance. An injured human being (or set of humans) may similarly heal. This idea of resilience as a concept of inertia is certainly worth considering but changes of position over time are often irreversible in a negative or positive sense. The ability of ecosystems or human beings to recover is often limited.

Decision-trees of a special kind can be used to illuminate or illustrate such impacts and options. At time t0 one alternative is to carry out a road construction project on a piece of agricultural land, implying that the road is completed at time t1 with some possibilities to modify things through new decisions at t1 or later. A second alternative at t0 is to safeguard agricultural production for future purposes. A new decision about land-use can be taken at t1 to continue agricultural production or choose some other land-use alternative. There is a value in these remaining options at t1 to be considered already at t0. Analysis in positional terms can be compared to conventional decision trees where the result when following a branch through the tree is expressed as “payoffs”, thought of as single numbers in monetary terms. As part of the present political economics perspective, the impacts or results are rather described as positions in multidimensional (nonmonetary and monetary) terms at various future points in time with the expected options connected with those positions. “Value” or “valuation”, to the extent that these words are used, becomes a matter of compatibility with each actor’s ideological orientation.

- Review Article

- Abstract

- The Concept of Ideology in Economics

- Sustainability as an Ideological Challenge

- Reconsidering Economics

- A Conceptual Framework for Sustainability

- Positional Analysis – A Democracy-Oriented Approach

- Decision Making in Multiple Steps

- Accounting for Sustainability

- Complexity and the Roles of Analyst and Decision Maker

- Concluding Comments

- References

Accounting for Sustainability

Present accounting practices are well established and attempts to change these practices will probably encounter some cognitive and emotional inertia. At the business level we are used to profit and loss statements and balance sheets in monetary terms and to GDP accounts at the national level. In relation to sustainability, non-monetary accounts are needed. Conventional accounting practices are described by Judy Brown as monologic as opposed to dialogic approaches very much needed Brown [14,15]. The latter kind of approach is democracy-oriented and starts with a recognition of the existence of multiple ideological orientations in relation to the practices of an organization or a nation. In a book chapter “On the need for broadening out and opening up accounting” Brown lists additional recommendations as follows:

i. Avoid monetary reductionism.

ii. Be open about the subjective and contestable nature of calculations.

iii. Enable accessibility for non-experts.

iv. Ensure effective participatory process.

v. Be attentive to power relations.

vi. Recognize the transformative potential of dialogic accounting.

vii. Resist new forms of Monologist Brown [14].

From a sustainability point of view, environmental degradation (or improvement) according to indicators in nonmonetary positional terms is of special importance. Health degradation (improvement) of a population or of those connected with an organization can similarly be made visible as time series regarding specific indicators. Standardization of accounting practices in the broader sense is perhaps not easily achieved. But each organization with its specific features can try to develop and improve its own standards over time. It should finally be made clear that approaches to decision making and accounting are not completely different things. They can interact in a destructive or supportive way from a sustainability point of view. Elements of Positional Analysis can be useful in attempts to develop accounting practices and vice versa.

- Review Article

- Abstract

- The Concept of Ideology in Economics

- Sustainability as an Ideological Challenge

- Reconsidering Economics

- A Conceptual Framework for Sustainability

- Positional Analysis – A Democracy-Oriented Approach

- Decision Making in Multiple Steps

- Accounting for Sustainability

- Complexity and the Roles of Analyst and Decision Maker

- Concluding Comments

- References

Complexity and the Roles of Analyst and Decision Maker

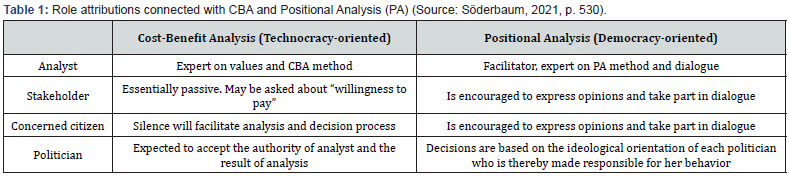

CBA is built on a traditional idea of expertness that is simplistic and technocratic at the same time (left-hand side of (Table 1). The analyst is an expert on the method to be applied (CBA) and on the ideological orientation or the values to be applied, guiding all actors to a conclusion considered optimal. Actors other than the analyst, such as stakeholders, those concerned, and politicians (or other decision-makers) need only listen and respect the authority of the analyst. Positional Analysis (PA) claims to be a democracyoriented approach (right-hand side of (Table 1). The economist as analyst is rather a “facilitator”. She is an expert on the PAmethod and on dialogue with all actors affected or concerned. Stakeholders, citizens and politicians are all encouraged to express their opinions and participate in problem-solving and dialogue, a dialogue that exposes conflicts of interest and differences in ideological orientation. The analyst (and all others) may learn from this interaction, and ideological orientations not previously considered may be articulated. The set of alternatives considered may similarly change as well as expectations about impacts in profile terms. As previously argued, open-mindedness and many-sidedness (rather than manipulation) are desired attitudes. Power relationships are certainly involved but they are made more visible rather than remain hidden. And all actors are regarded as Political Economic Persons and responsible for their behavior or action. The ideological orientations considered in a decision situation need not be limited by the preferences of those immediately concerned, for example in a local context. If a nation has signed the Paris Agreement of 2015 concerning climate issues or accepted the 17 United Nations SDGs, then the analyst should bring in such goals into analysis even when local politicians are inclined to forget about or downplay them. The purpose of PA is to bring competing ideological orientations into analysis. In this way traditional ideological orientations will be challenged.

- Review Article

- Abstract

- The Concept of Ideology in Economics

- Sustainability as an Ideological Challenge

- Reconsidering Economics

- A Conceptual Framework for Sustainability

- Positional Analysis – A Democracy-Oriented Approach

- Decision Making in Multiple Steps

- Accounting for Sustainability

- Complexity and the Roles of Analyst and Decision Maker

- Concluding Comments

- References

Concluding Comments

Sustainability problems can be understood in more ways than one. Neoclassical economists tend to see problems in terms of the functioning of markets. Markets may fail but when this is the case new markets can be arranged. In the kind of “institutional ecological economics” presented here, the market is not the only institution that can function well or fail. Also, business corporations and public organizations, for example universities can fail. Even individuals as politicians or in other roles need to be scrutinized. Our reference to democracy suggests that theoretical perspectives in economics need to be discussed as part of a pluralist attitude. There are different kinds of heterodox economics to be considered Jakobsen, Fullbrook & Morgan, Beker [16-18,19] and these perspectives differ not only in scientific but also in ideological terms. Ideologies and ideological orientations need to be clarified as well as possible and not hidden. It has been argued that neoclassical economic theory and method is specific in ideological terms. It should similarly be made clear that also each heterodox perspective, such as the one presented in this article is specific in ideological terms. When it becomes clear among all categories of economists that there is no value-free or neutral economics, then the prospects for a constructive dialogue will improve. Economics must be compatible with democracy.

- Review Article

- Abstract

- The Concept of Ideology in Economics

- Sustainability as an Ideological Challenge

- Reconsidering Economics

- A Conceptual Framework for Sustainability

- Positional Analysis – A Democracy-Oriented Approach

- Decision Making in Multiple Steps

- Accounting for Sustainability

- Complexity and the Roles of Analyst and Decision Maker

- Concluding Comments

- References

References

- Mankiw N, Gregory, Mark P Taylor (2011) Economics (Second edition). Cengage Learning EMEA, Andover, UK.

- Robinson, Joan (1962) Economic Philosophy. CA. Watts & Company, London.

- North Douglass C (1992) Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge p. 23.

- Myrdal, Gunnar (1978) Institutional Economics. J Econom Issue 12(4): 771-783.

- Kuhn Thomas S (1970) The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (Second edition). University of Chicago Press, Chicago, Ill.

- United Nations (2015) Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

- Söderbaum Peter (2017) Mainstream economics and alternative perspectives in a political power game, in Brown Judy, Peter Söderbaum and Malgorzata Dereniowska “Positional Analysis for Sustainable Development. Reconsidering Policy, Economics and Accounting”. Routledge, London p. 22-28.

- Söderbaum Peter (2019) Reconsidering economics in relation to sustainable development and democracy, Journal of Philosophical Econom 3(1): 19-38.

- Håkansson, Håkan, Ivan Snehota (2017) No Business is an Island. Making Sense of the Business World. Emerald Publishing, Bingley, UK.

- Bode Thilo (2018) Die Diktatur der Konzerne. Wie globale Unternehmen uns schaden und die Demokratie zerstö S. Fischer Verlag, Frankfuurt am Main.

- Söderbaum Peter (2000) Ecological economics. A political economics approach to environment and development. Earthscan, London.

- Brown, Judy, Peter Söderbaum, Malgorzata Dereniowska (2017) Positional Analysis for Sustainable Development. Reconsidering Policy, Economics and Accounting. Routledge, London.

- Söderbaum Peter (2021) Democracy, ideological orientation and sustainable development, Chapter 28, in Crawford, Gordon and Abdul-Gafaru Abdulai eds, Democracy and Development. Elgar Handbooks in Development. Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham pp. 522-535.

- Brown Judy (2017) On the need for broadening out and opening accounting, Chapter 5 pp. 45-60.

- Brown, Judy, Jesse Dillard, Trevor Hopper (2015) Accounting, accountants and accountability regimes in pluralistic societies: taking multiple perspectives seriously, Account Auditing Accountabil J 28(5): 626-650.

- Jakobsen, Ove (2017) Transformative Ecological Economics. Process Philosophy, Ideology and Utopia (Routledge Studies in Ecological Economics). Routledge, London.

- Fullbrook Edward, Jamie Morgan (2019) Economics and the Ecosystem. World Economics Association Books, Bristol.

- Beker Victor A (2020) Alternative Approaches to Economic Theory. Complexity, Post-Keynesian and Ecological Economics. Routledge, London.

- Piketty Thomas (2020) Capital and Ideology. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass.