- Review Article

- Abstract

- Introduction

- What are the Sustainable Development Goals?

- What is the importance of sustainable development?

- What is development?

- What is a Developed Nation?

- What Is a Developing Country?

- Which Countries Have the Highest GDP per Capita?

- What Does HDI Mean?

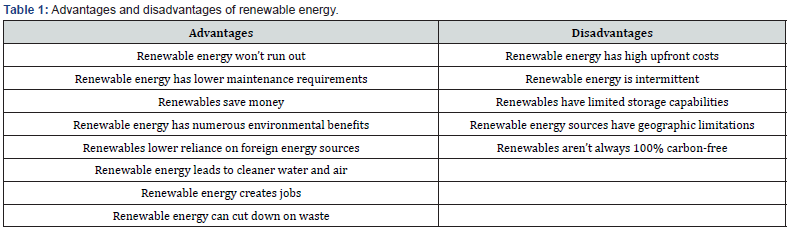

- Advantages and Disadvantages of Renewable Energy

- Disadvantages of Renewable Energy

- References

A Unique Modality for Green Management

Mohammad Maghferati1 and Pourya Zarshenas2*

1M.B.A Student of University of Northampton, Niloofar Abi Health and Sports Complex Management, England

2Master of Technology Management (R&D Branch), South Tehran Branch, Islamic Azad University (IAU), Tehran, Iran, Universal Scientific Education and Research Network (USERN), Tehran, Iran

Submission: July 24, 2023; Published: August 17, 2023

*Corresponding author: Pourya Zarshenas, Master of Technology Management (R&D Branch), South Tehran Branch, Islamic Azad University (IAU), Tehran, Iran, Universal Scientific Education and Research Network (USERN), Tehran, Iran

Mohammad M, Pourya Z. A Unique Modality for Green Management. Recent Adv Petrochem Sci. 2023; 8(1): 555727.DOI: 10.19080/RAPSCI.2023.08.555727

- Review Article

- Abstract

- Introduction

- What are the Sustainable Development Goals?

- What is the importance of sustainable development?

- What is development?

- What is a Developed Nation?

- What Is a Developing Country?

- Which Countries Have the Highest GDP per Capita?

- What Does HDI Mean?

- Advantages and Disadvantages of Renewable Energy

- Disadvantages of Renewable Energy

- References

Abstract

Energy economics is the field that studies human utilization of energy resources and energy commodities and the consequences of that utilization. In physical science terminology, “energy” is the capacity for doing work, e.g., lifting, accelerating, or heating material. In economic terminology, “energy” includes all energy commodities and energy resources, commodities or resources that embody significant amounts of physical energy and thus offer the ability to perform work. Energy commodities - e.g., gasoline, diesel fuel, natural gas, propane, coal, or electricity - can be used to provide energy services for human activities, such as lighting, space heating, water heating, cooking, motive power, electronic activity. Energy resources - e.g., crude oil, natural gas, coal, biomass, hydro, uranium, wind, sunlight, or geothermal deposits - can be harvested to produce energy commodities. Energy economics studies forces that lead economic agents - firms, individuals, governments - to supply energy resources, to convert those resources into other useful energy forms, to transport them to the users, to use them, and to dispose of the residuals. It studies roles of alternative market and regulatory structures on these activities, economic distributional impacts, and environmental consequences. It studies economically efficient provision and use of energy commodities and resources and factors that lead away from economic efficiency.

Keywords: Management; R&D Management; Research and Development; Development; Sustainable Development

- Review Article

- Abstract

- Introduction

- What are the Sustainable Development Goals?

- What is the importance of sustainable development?

- What is development?

- What is a Developed Nation?

- What Is a Developing Country?

- Which Countries Have the Highest GDP per Capita?

- What Does HDI Mean?

- Advantages and Disadvantages of Renewable Energy

- Disadvantages of Renewable Energy

- References

Introduction

Economic Energy

Energy economics studies energy resources and energy commodities and includes forces motivating firms and consumers to supply, convert, transport, use energy resources, and to dispose of residuals; market structures and regulatory structures; distributional and environmental consequences; economically efficient use. It recognizes:

1. Energy is neither created nor destroyed but can be converted among forms;

2. Energy comes from the physical environment and ultimately returns to it.

Humans harness energy conversion processes to provide energy services. Energy demand is derived from preferences for energy services and depends on properties of conversion technologies and costs. Energy commodities are economic substitutes. Energy resources are de-pletable or renewable and storable or non-storable. Human energy use is dominantly de-pletable resources, particularly fossil fuels. Market forces may guide a transition back to renewable resources. Inter-temporal optimal de-pletable resource extraction paths include an opportunity cost or rent. World oil prices remain above pre-1973 levels and remain volatile as a result of OPEC market power. Oil supply disruptions of the 1970s led to economic harm. Environmental damages from energy use include climate change from greenhouse gases, primarily carbon dioxide. Environmental costs not incorporated into energy prices (externalities) lead to overuse of energy and motivate policy interventions.

Energy economics is the field that studies human utilization of energy resources and energy commodities and the consequences of that utilization. In physical science terminology, “energy” is the capacity for doing work, e.g., lifting, accelerating, or heating material. In economic terminology, “energy” includes all energy commodities and energy resources, commodities or resources that embody significant amounts of physical energy and thus offer the ability to perform work. Energy commodities- e.g., gasoline, diesel fuel, natural gas, propane, coal, or electricity- can be used to provide energy services for human activities, such as lighting, space heating, water heating, cooking, motive power, electronic activity. Energy resources- e.g., crude oil, natural gas, coal, biomass, hydro, uranium, wind, sunlight, or geothermal deposits- can be harvested to produce energy commodities. Energy economics studies forces that lead economic agents- firms, individuals, governments - to supply energy resources, to convert those resources into other useful energy forms, to transport them to the users, to use them, and to dispose of the residuals. It studies roles of alternative market and regulatory structures on these activities, economic distributional impacts, and environmental consequences. It studies economically efficient provision and use of energy commodities and resources and factors that lead away from economic efficiency. The first task to understand any concept in general is to provide a basic definition of it. Here we want to first provide a basic definition of this branch of science and then proceed to examine its characteristics. According to the definition, energy economy is one of the scientific branches that deals with energy supply and demand. Academically, energy economics is considered a subset of economics. The topics of interest in this branch of economics, in addition to using the topics of economics itself such as econometrics, environmental economics, micro and macroeconomics and of course resource economics, but also with other branches of science and engineering such as geology, energy engineering, bio Science and politics are also involved; So, in general, in answer to the question of what is energy economy, we can answer that it is an interdisciplinary field that deals with how energy is supplied and issues related to its demand. In the following, we will introduce each of the examined axes of energy economy separately and examine the applications and goals of this branch of knowledge in detail. The problems and applications of energy supply checking energy supply is one of the most important issues of energy economy, which has its own challenges and applications. The issue of energy supply is most closely related to econometrics and energy engineering. Investigating the potential of energy extraction by solar, wind, geothermal energy methods is one of the main topics of this part of energy economy. Because energy is inherently finite; so, its value in the cycle of supply and storage is checked in a different way from other goods [1-10].

Today’s challenge of this branch of energy economy is to determine how energy is valued and to find a way to prevent its waste. Its applications are also seen in the discussion of finding the potential and economic justification of using different forms of energy. So, in answer to what is energy economy, it should be said that one of its topics is to examine how energy is supplied.

Energy demand and its challenges. We should focus on another part of economics study which is called energy demand. Although energy supply is an environmental issue, energy demand is a social issue because all countries in the world need energy. To the extent that all the economic models of today’s world are written based on the energy factor. The issues facing this part of energy economy include finding the relationship between energy demand and development, energy demand management systems, and the relationship between economic growth and energy demand. Its applications are also seen when writing the model of economic progress or closing the budget of countries; because one of the key elements in the economic management of countries is energy. Energy markets among the other areas studied in this type of economy are energy markets. The energy market is the scene where energy supply and demand occur. The issues facing the market strongly depend on the type of energy in question. For example, the nuclear energy market completely depends on the political conditions of the supply and demand countries, the regional situation of the countries, and how energy is supplied. This section is used in the discussion of creating a global village and free electricity for all countries, but it faces challenges such as technology transfer, the controlling variables of the global energy market, how to distribute different energies and the contribution of each country in its supply and demand. Energy efficiency is another very important topic in energy economy is the issue of energy efficiency. Energy efficiency generally examines whether the cost of supplying energy is economical or not. For example, with conventional power plants to produce electricity, is it profitable to supply the entire electrical system of a city with solar cells?

One of the most general challenges is the examination of the costs incurred to replace non-renewable energies such as solar and wind energy with renewable energies; If, on the assumption of a country, it is estimated that in the future, due to the reduction of oil, the cost of importing it into the country will be higher than the cost of setting up solar power plants; Therefore, he should be able to plan for energy efficiency and perform this replacement process in the most optimal way possible. Also, one of its most important applications is planning to reduce global warming and replace more efficient energy instead of fossil fuels.

Problems and applications of energy supply to the environment Perhaps one of the biggest challenges facing the energy economy after the risk of running out of non-renewable energies is the environmental issues and challenges of energy supply. We all know that after the industrial revolution, the use of coal as the main source of energy caused irreparable damage to nature. One of its results is the depletion of the ozone layer. Its other disadvantages are the destruction of a large number of animal species, the reduction of forest cover and the drying up of some rivers, which are almost irreparable; so, it is very important that we use an energy source that does not harm the nature.

For this reason, a concept called clean energy has been created, which is one of the other topics that is said in the answer to what is energy economy. Any energy that ultimately leads to damage to nature and is generally renewable is called clean energy. Geothermal energy, wind energy, solar energy, sea wave energy, etc. are among the clean energies that should replace fossil fuels. But this replacement in a way that is optimal is an issue that is studied in energy economy. Economic growth and its impact on energy as energy is a very important and influential factor on the economy, economic growth also has an important impact on the fluctuations of the energy market. One of the very interesting examples that is always studied by economists is the emergence of the economic growth of two countries, India and China, and its effect on the increase in oil prices. After two countries, China and India, experienced strong economic growth in a short period of time, their heavy demand for energy imports caused the price of oil to experience a lot of growth in a short period of time. Economic growth and its impact on energy on the other hand, this increase causes other emerging economic competitors to be left behind from rapid growth and experience lower economic growth; therefore, energy has an undeniable effect on economic growth and also affects energy price changes. One of its applications is to examine the energy market and its impact on the economic growth of different countries and predict the direction of the world’s emerging economic powers [11-20].

Engineering Economic

Engineering economics is the application of economic principles and calculations to engineering projects. It is important to all fields of engineering because no matter how technically sound an engineering project is, it will fail if it is not economically feasible. Engineering economic analysis is often applied to various possible designs for an engineering project in order to choose the optimum design, thereby taking into account both technical and economic feasibility. Many basic economic principles may be applied in an engineering economic analysis, depending on their applicability. Time value of money is one such principle with wide applicability. This principle is used to calculate the future value of something given the present value, or the present value given the future value, at a given interest rate. For example, time value of money may be used to calculate how much a project will cost once it is actually completed; annual investments or withdrawals may also be calculated. A cash-flow diagram is often used to aid in the calculation of the time value of money.When comparing costs among two or more possible alternatives, engineering economics may use either present or future worth analysis or annual cost.

Engineering economics is one of the branches of economics and discusses the analytical methods used in cost estimation and determining the value of systems, products and services. This unit is one of the most basic and widely used courses in industrial engineering at the master’s level. During the bachelor’s course of this field, the concepts of economics were discussed, and in the master’s degree, this topic was discussed in a wider way and using various methods to solve economic problems. Engineering economics is one of the branches of economics and discusses the analytical methods used in cost estimation and value determination of systems, products and services. Success in solving engineering problems often depends on the ability and consideration of both economic and technical factors. Engineers must take responsibility for the economic interpretation of their work. In order to establish the relationship between the technical and economic aspects of engineering work, it is necessary for engineers to master the basic concepts of economic analysis. Engineering economics is a set of techniques that simplify the process of comparison between selectable options based on economic principles. Engineering economics is actually a tool for choosing the best or, in other words, the most economical option among the options before engineers. In other words, engineering economy is the main decision-making tool of engineers in projects. The scientific and technical issues raised during the academic courses of the engineering fields have put different options in front of them to carry out the tasks assigned to the engineers, all of which are applicable from a technical and engineering point of view. However, it is the engineering economy that determines which of the technically applicable options are economically justified and which are not economically justified. In other words, if the technical ability to implement options and engineering projects is a necessary condition for their implementation, their financial ability or “economic justification” will also be a sufficient condition for their implementation. Engineering economics specifically deals with the second category, which is the examination of the economic justification of the options faced by engineers. The need for engineering economics was felt since engineers turned to economic analysis of decisions related to engineering projects. Engineering economics is actually the beating heart of the decision-making process. Decisions discussed in engineering economics include basic elements such as cash flows, time and interest rates. Finally, engineering economics helps to make better and more economical decisions using logical and mathematical methods. Success in solving engineering problems often depends on the ability and consideration of both economic and technical factors. Engineers must take responsibility for the economic interpretation of their work. In order to establish the relationship between the technical and economic aspects of engineering works, it is necessary for engineers to master the basic concepts of economic analysis. In defining what engineering economics is, it will be helpful to know what engineering economics is not. Engineering economics is not a process or method for determining what options are available to choose from. On the contrary, the mission of engineering economics begins exactly after the stage of identifying selectable options. If the best option is really an option that the engineer has not identified as a selectable option, then it is obvious that using all the analytical tools of engineering economics will not lead to the selection of that option. Engineering options typically include items such as purchase cost (initial cost), expected useful life, annual asset maintenance costs (asset operating and maintenance costs), anticipated increase in resale value (salvage value), and is the interest rate. After collecting relevant statistics, figures and estimates, engineering economics analysis can be a guide to determine the best option from the point of view of economics [21-30].

Economics is the science of allocating scarce resources with unlimited wants and goals in mind. Therefore, scarce resources should be used wisely and effectively at the optimal level so that costs are minimized, and profits are maximized. All decisions in engineering also include possible options and choices. These possible options should be carefully evaluated before implementation. “Engineering Economics” is, in fact, a systematic evaluation of the economic value of solutions presented to engineering problems. That these solutions are economically acceptable and show more benefits than losses in the long run. In simple words, engineering economics is the application of a set of mathematical methods to economically analyze industrial projects in order to choose the most economical project.

History Of Engineering Economics

Engineering economics as a branch of science does not have a long life. Of course, this does not mean ignoring the costs in making engineering decisions in the past. The book “The Economic Theory of Railway Location” by Arthur M. Wellington - a civil engineer - pioneered engineering’s interest in economic evaluation. A book titled “Principles of Engineering Economy” was published in 1930 by Eugene Grant. Grant is considered the father of engineering economics. New developments in the field of this science have led to the emergence of new methods in the field of risk assessment, sensitivity, resource conservation and effective use of public funds. What topics are raised in engineering economics?

Among the topics raised in engineering economics, the following can be mentioned.

• Economics of management, performance and growth and profitability of engineering companies

• Examining the trends and issues of engineering economics from a macro perspective

• Engineering products market and demand effects

• Development, marketing and financing of new technologies and engineering products

• Ratio of benefits to expenses

Management Economical

Managerial economics is a branch of economics involving the application of economic methods in the organizational decisionmaking process. Economics is the study of the production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services. Managerial economics involves the use of economic theories and principles to make decisions regarding the allocation of scarce resources. It guides managers in making decisions relating to the company’s customers, competitors, suppliers, and internal operations. Managers use economic frameworks in order to optimize profits, resource allocation and the overall output of the firm, whilst improving efficiency and minimizing unproductive activities. These frameworks assist organizations to make rational, progressive decisions, by analyzing practical problems at both micro and macroeconomic levels. Managerial decisions involve forecasting (making decisions about the future), which involve levels of risk and uncertainty. However, the assistance of managerial economic techniques aid in informing managers in these decisions [31-40].

Managerial economists define managerial economics in several ways:

1. It is the application of economic theory and methodology in business management practice.

2. Focus on business efficiency.

3. Defined as “combining economic theory with business practice to facilitate management’s decision-making and forwardlooking planning.”

4. Includes the use of an economic mindset to analyze business situations.

5. Described as “a fundamental discipline aimed at understanding and analyzing business decision problems”.

6. Is the study of the allocation of available resources by enterprises of other management units in the activities of that unit.

7. Deal almost exclusively with those business situations that can be quantified and handled, or at least quantitatively approximated, in a model.

Economic Management

In fact, it is theories, tools and methods to solve practical problems in a business using economic concepts. In other words, management economics is a combination of economics and management theories. In fact, management economics is the link between theoretical theories and practical work and helps managers make better decisions. Sometimes this term is referred to as business economics, and it is a branch of economics that applies microeconomic analysis to the decision-making methods of businesses or other management units. In this way, management economics is the bridge connecting theoretical economics to practical economics. And it is very far from quantitative techniques such as regression analysis, correlation and differential and integral calculus. If there is a subject in management economics that the majority in which they are unanimous, it is an effort to optimize business decisions according to the company’s goals and the constraints that have been imposed. For example, using operations research, mathematical programming and game theory for strategic decision-making and other computational methods. Management economics refers to the application of economic theory and decision-making science analysis tools and examines how an organization can effectively reach its goals and objectives. In management economics, many aspects of economic theory and analysis tools in different fields of business management are studied together.

Development Economical

Economic Development is programs, policies or activities that seek to improve the economic well-being and quality of life for a community. What “economic development” means to you will depend on the community you live in. Each community has its own opportunities, challenges, and priorities. Your economic development planning must include the people who live and work in the community. Economic development, also known as economic growth or advancement, refers to the generation of wealth that is found in the benefit and advancement of society. It is not only found in isolated development projects, but in the general advancing of the economy with respect to factors like education, resource availability, and living standards. Economic development pertains to the buildout of education systems, recreational parks, and public safety infrastructure. The importance of economic development lies in the wellbeing of the population. The concept of development is a key factor in the decision-making process of sovereign authorities when designing policies. Economic development relies heavily on the efficient allocation of resources (a reason for the slow growth of command economies). Development isn’t exclusively found in projects, but also in approaches to economics like how resources are allocated to industries that need those most. The stimulus of trade through policies, laws, and regulations is another measure of promoting economic growth [41-50].

Private sector investment is very important for development, especially in free market economies (consumer-centric economies). In command economies (government-centric) the private sector contributes little to the advancement of the general economy. This is due to how command governments own the means of production, which results in their decisions being most crucial to economic growth. Contrary to command economies, in free market economies, the projects and expansions that private enterprises deem necessary play a key role in the general growth of the whole economy. The private ownership of property and production factors leads to the shrinking influence of the government.

Economic Development

Development economics involves the creation of theories and methods that help determine policies and practices that can be implemented at both the local and international levels. This may involve market incentives or mathematical methods such as temporal optimization for project analysis or a mixture of both quantitative and qualitative methods. Unlike many other sectors of the economy, the approach of development economics may include social and political factors to design and formulate specific programs. Also, unlike many other areas of economics, there is no consensus on what students should know. However, many scientists believe that development economics has a series of fixed principles. How many questions did they ask themselves to achieve this? If we pay attention to the economic and cultural history of nations, what constant factors will we find in their economic development? Is there a level that a person should follow in economic development apart from choosing values, although the development during this period in every country has had a specific format and has been achieved in different proportions, but a definite and fixed level can be observed and deduced in them. The topic of development economics has been raised more than any other topic in the field of economics.

If we want to introduce development economics as one of the important subjects in the economic field, we must say that it is an important branch of economics whose main subject is the examination and analysis of the development process in lowincome and less developed countries, especially third world countries, using multiple methods. . In general, development economics focuses on improving financial, economic and social conditions in developing countries, and with the aim of improving conditions in the world’s poorest countries, factors such as health, education, working conditions, domestic and international policies, market conditions, and macroeconomic and microeconomic factors related to It examines the structure of developing economies and domestic and international economic growth. In simpler terms, it studies the transformation of emerging countries into more prosperous countries. Of course, there are several definitions about this branch of economics. The reason for such a wide variety of definitions can be seen as the excessive complexity of development economics. For example, some economists have defined it as a science whose task is to examine the quantitative and qualitative growth of each country in the gross national production. Development economics is the process by which the economic well-being and quality of life of a nation, region, local community or an individual is improved based on targeted goals and objectives. Development economics is a special field of economics that studies the process of growth and development. So that this science is studied and investigated within a country.

Since a country is highly dependent on economic development and growth in its expansion process, development economics can be used in a wide range of ways; but this does not mean the exclusive use of development economics in economic activities. This part of the economy, in the form of theories and methods, is used for policy making and can improve the conditions of a country in a wide range. The improvement of the situation requires changes and reforms in various components and factors that are possible through the development economy. Paying attention to development has been one of the most important issues from the past until now, that’s why economic approaches have been in the center of people’s attention and have shown themselves in political and social dimensions. Theorists propose development economics in the form of variables; while no special teaching about development economics has been introduced so far and there is no fixed format for it; some economists propose fixed principles for it.

Green Management

Green management is when a company does its best to minimize processes that harm the environment. This means turning to practices that are environmentally friendly. Some short-run cost-effective benefits are: Improved health. Green management is an approach to organizational management that seeks to reduce the environmental impact of business operations while improving business efficiency and profitability. The focus of green management is on sustainability, and it involves making decisions and taking actions that are environmentally responsible, socially beneficial, and economically viable. This will discuss the concept of green management, its importance, benefits, and challenges, as well as strategies for implementing green management practices in organizations.

The Concept of Green Management

Green management is a proactive approach to managing a business in a way that minimizes the environmental impact of its operations. It involves adopting strategies and practices that reduce waste, conserve energy and natural resources, and minimize pollution. Green management goes beyond simply complying with environmental regulations; it involves taking a leadership role in environmental stewardship and sustainability. Green management practices can be applied in any industry, from manufacturing to retail, hospitality to transportation. Organizations that adopt green management practices can realize a range of benefits, including cost savings, enhanced brand reputation, increased customer loyalty, and improved.

Importance of Green Management

The importance of green management lies in its potential to create a sustainable future for our planet. The need for sustainable business practices has become increasingly urgent in recent years, as the global population continues to grow and consume more resources. Organizations that fail to adopt sustainable practices are likely to face significant risks, including financial losses, reputational damage, and regulatory penalties. In addition to mitigating risk, green management can also create significant business opportunities. The demand for sustainable products and services is growing rapidly, and organizations that can meet this demand are likely to benefit from increased sales and revenue. Moreover, adopting green management practices can lead to cost savings by reducing waste, energy consumption, and other resource use.

Benefits of Green Management

The benefits of green management can be significant and wide-ranging. Some of the key benefits include:

1. Cost Savings: Green management practices can help organizations reduce costs by conserving energy and natural resources, reducing waste, and improving operational efficiency.

2. Enhanced Brand Reputation: Organizations that adopt green management practices are often perceived as socially responsible and environmentally conscious, which can enhance their brand reputation and appeal to customers.

3. Increased Customer Loyalty: Customers are increasingly aware of the environmental impact of the products and services they consume. Organizations that can demonstrate a commitment to sustainability are more likely to retain loyal customers.

4. Improved Employee Morale: Green management can help create a more engaged and motivated workforce by demonstrating a commitment to environmental responsibility and sustainability.

5. Regulatory Compliance: Organizations that adopt green management practices are more likely to comply with environmental regulations, reducing the risk of fines, legal action, and reputational damage.

Green management is an essential approach for organizations that want to operate sustainably and responsibly. The benefits of green management can be significant, including cost savings, enhanced brand reputation, and improved employee morale. However, implementing green management practices can also be challenging, and requires a structured approach that includes assessing current environmental impact, setting goals and targets, developing a green management plan, implementing green management practices, monitoring and measuring performance, and communicating and engaging with employees and stakeholders. By following this approach, organizations can create a more sustainable future while achieving their strategic objectives [51-60].

Green Economy

The term green economy was coined for the first time in 1989 by a group of environmental economists in a report titled “Green Economy Plan” to be presented to the UK government. The aforementioned report was prepared in order to provide recommendations to the British government in this regard if there was an agreed definition of the term “sustainable development” and its concepts for measuring economic growth and evaluating policies and projects. In 1991 and 1994, Following the first report, reports titled “Greening the World Economy” and “Measuring Sustainable Development” were presented. In 2008, the term “green economy” was revived during the debates to find a policy that responds to various global crises. Three related concepts “green economy, green growth and low-carbon development” While the concept of green economy has recently attracted the attention of international communities, green economy policies have been studied for decades by economists and academics, especially in the field of environmental economics and economics. Ecological, has been investigated and analyzed. The green economy policy tools were also discussed during international negotiations, including the UN Sustainable Development Commission. For example, the Rio statement includes the principles of using economic tools and promoting the internalization of environmental costs (principle 16) and limiting unsustainable production and consumption (principle 8). Ten years later, the action plan of Johannesburg identified the need to change the way of production and consumption of societies and proposed the framework of 10-year development plans for sustainable production and consumption.

Principles of Green Economy

1. Green economy is a tool to achieve sustainable development.

2. Green economy should create decent work and green jobs.

3. Green economy includes the efficiency of resources and energy.

4. Green economy respects planetary boundaries and environmental limits.

5. Green economy uses integrated decision making.

6. The process of measuring the green economy is beyond GDP using appropriate indicators and criteria.

7. The green economy is fair and just between countries and within them and between generations.

8. Green economy protects biodiversity and ecosystems.

9. Green economy leads to reduction of poverty, welfare, livelihood, social support and access to essential services.

10. Green economy improves governance and rule of law. Also, green economy inclusive, democratic, it is collaborative, responsive, transparent and stable.

11. Green economy internalizes external aspects (including environmental costs, etc.).

In general, green economy means sustainable economy or environmentally friendly economy. The term green economy was first coined by an economist named Paul Yers in 1989 in a book called A Blueprint for a Green Economy. Traditional economy is based on economic growth and development, but in green economy, the goal will be sustainable environmental development. The United Nations Environment Program has provided a definition of this concept as “green economy is an economy that results in advanced human welfare and social equality, while reducing environmental risks and ecological deficiencies, leading to economic growth.” There are two perspectives to achieve sustainability in the field of green economy, which are: 1) The improvement of economic conditions should not be limited by environmental concerns, and environmental problems should be completely abandoned. 2) Sustainable economic development must be accompanied by maintaining and improving the quality of the environment. Of course, the second view is correct because ignoring environmental problems threatens the sustainability of the economy in the long run. Environmental sustainability is a process that adjusts environmental interactions with the idea and attitude of preserving the environment based on ideal behavior. Sustainability in the use of the environment requires that humans use natural resources to the extent that these resources can be replaced naturally. Increasing the use of resources and reducing waste is the main goal of sustainable natural resource management. In the green economy, “green energy”, which is based on renewable energy, is trying to replace green energy instead of fossil fuels and to save energy for the time being. Necessity pays. But the high cost of green energy and of course the failure of the market related to the issue of environmental protection and global warming due to the side effects and high costs of research, development and marketing for green energy and the products obtained from it causes factories to and companies show less desire to work and invest in this field. For this reason, green energy and green products need the help of governments to expand. The Renewable Energy Act among European Union countries and the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 were passed to help this market. Therefore, jobs that are related to energy production and clean and environmentally friendly products are called green jobs, the owners of these jobs are required to comply with occupational health and safety standards in their respective job units. According to the latest research of the technical and professional organization of the country, about 230 green job titles have been identified, including water resource specialists, technicians and installers of solar energy (heating) devices, carpenters and carpenters, construction workers, managers Construction, agricultural technicians, industry ecologists, electrical engineers and engineering and architecture managers mentioned.

But the criterion that places these jobs in the ranks of the green ones depends on what methods and methods the owners of each of these jobs choose to advance their goals, what their strategies are and what they ultimately achieve. Now, in many countries of the world, training and empowering people in the field of environmental protection along with economic development is considered a key and strategic principle, and they consider the implementation of environmental standards to benefit economic activity and industrial development. Therefore, it seems that the creation of green economy development solutions in our country can establish a link between industry and environment while curbing environmental crises and unemployment phenomenon. Green jobs reduce energy consumption and produce less and recyclable waste, and therefore help to reduce the cost of many economic enterprises and preserve nature and the environment. The expansion of green jobs while increasing the motivation and improving the productivity of the workforce, development Healthy work environments reduce accidents and create more jobs. Now I want to examine the V&M medal based on different economies such as energy economy, engineering economy, management economy, development economy, especially green economy. According to the above explanations, I realized that no business, if it takes a step towards health and green management, can have the most support for the ecosystem with the nobles of the sciences that were mentioned. Considering the energy economy, I realized that energy supply is one of the The most important issue is energy economy and it is most related to econometrics and energy engineering. Investigating the potential of energy extraction using solar, wind, and geothermal energy methods is one of the main topics of this part of energy economy, because energy is inherently exhaustible, especially oil and gas, which are not only the issue of their exhaustibility, but also the damage they bring to the ecosystem, so the use of energy is required. renewable sources are mentioned here and these sources must be used for energy supply, such as the use of solar cells on the facade of the building, which leads to the reduction of electricity costs, etc. that have the least energy loss;

For example, the use of heavy materials with high thermal capacity, such as concrete, bricks and cement blocks, increases the thermal stability of the building; In other words, when the outside temperature changes, the air inside the house does not get too cold or hot. Also, the use of hollow bricks in the construction of external walls makes these bricks hold more air; Therefore, the thermal capacity of the building increases. Or the use of new materials and insulation, all of which somehow prevent energy loss. We can even consider the clothing of the personnel, for example, clothes with recycled materials that are twice as Let nature return. We have different brands that produce clothes from ocean waste and bottle caps that can be used twice. They are good and environmentally friendly uniforms. Minerals and organic materials and biological resources are also seen in organically produced clothes. The next thing is the discussion of engineering economy, which should be decided to manage project costs and output with the best and highest quality materials, for example, green cleaning products use more natural and organic methods for cleaning. which have much less harm. Other measures that can be taken in order to optimize energy consumption are the use of environmentally friendly lamps, the purchase of low consumption electrical appliances, and connecting heating and cooling devices to the thermostat.

LED lamps are one of the best choices in order to protect the environment because they consume much, much less electricity and in this way the energy consumption of a building can be significantly reduced. One of the most important ways to reduce the energy consumption of buildings and in In line with that, more protection of the environment, intelligentized of buildings. By making buildings smart, energy consumption can be saved to an amazing extent. Of course, it should also be kept in mind that making smart has a high cost, but this cost is actually used to protect the environment and make people’s lives easier, which is definitely worth it. There is an approach in architectural design known as organic architecture. This type of architecture establishes a link between the building and its surroundings. The main thinking in relation to this type of architecture is that all people are part of nature and should remain part of it so as not to harm it. The founder of organic architecture is Frank Lloyd Wright. One of the important principles of organic architecture is that the building must be inspired by nature, natural materials and materials should be used in its construction, and any copying should be avoided in its design. One of the most important principles of environmentally friendly houses is saving water. Installing systems that collect rainwater and are used for watering plants and washing is one of the most important measures that can be taken to protect water. The rainwater collection system can also collect a large amount of water from the roof and other paths and reduce the amount of water demand for miscellaneous works. Another solution that is used in this field is installing faucets and automatic shower heads. Installing flush tanks that use less water and automatic washing machines are other practical solutions in the field of reducing water consumption. Green or living roofs are good choices.

The reason why these roofs are suitable is that they are good insulators and because of the growth and cultivation of plants, they clean the air and liven up the environment. Wooden shingle roofs or plank roofs, which are very environmentally friendly, but have a high price. Using recycled materials in the construction of roofs, such as recycled plastics, reduces waste production and is less expensive. In terms of economic management, considering that it plays a significant role in decision-making based on the goals of the collection, when the biggest goal of the collection is to be environmentally friendly, then all the consumables in the collection are intelligently purchased in bulk or ordered to be produced, for example Dishes or clothes and covers of all the utensils, napkins and dishes that are used are all organic and recyclable. In terms of economic development, during which the well-being and quality of a business are considered, it is possible to take a green look at the way of payment in the whole system, that with a credit card, you can use all the facilities of the restaurant, cafe, and center. Massage and the club used, and the exchange for the green and paperless payment method should be done with any kind of valid currency such as pounds and dollars, and considering points such as a free meal plan or sports tips for people who follow their health plans well through experts and the consultants of the complex are introduced and the development of maximum green space inside and outside the building.

Green management is not a cost, it is saving, green management is not a choice, it is a necessity! All of us humans are responsible for protecting the resources on earth such as water, soil, air, forest, etc. Minimize the environment. The planet we live on is the most important thing we humans have; Therefore, we must properly take care of the resources we have on earth. This is what is referred to as “green management”; In other words, we can say that green management is the effective and efficient use of all material and human resources to control and guide the organization to achieve environmental and planning goals. Just as the provision of appropriate services is considered very important and necessary for all organizations and institutions, attention to the environment and natural resources should also be important and become a part of our culture. Unfortunately, this issue has had very little importance in the past; But these days, due to the fact that the amount of air pollutants has increased a lot and also the production of waste and waste is increasing, the planet is facing a serious danger. Therefore, green management has become important and is no longer considered a choice, but a necessity so that we can provide greenery and life for ourselves and future generations.

Environmental Economics

The total environment includes not just the biosphere of Earth, air, and water, but also human interactions with these things, with nature, and what humans have created as their surroundings. As countries around the world continue to advance economically, they put a strain on the ability of the natural environment to absorb the high level of pollutants that are created as a part of this economic growth. Therefore, solutions need to be found so that the economies of the world can continue to grow, but not at the expense of public goods. In the world of economics, the amount of environmental quality must be considered as limited in supply and therefore is treated as a scarce resource. This is a resource to be protected. One common way to analyze possible outcomes of policy decisions on the scarce resource is to do a cost-benefit analysis. This type of analysis contrasts different options of resource allocation and, based on an evaluation of the expected courses of action and the consequences of these actions, the optimal way to do so in the light of different policy goals can be elicited. Further complicating this analysis are the interrelationships of the various parts of the environment that might be impacted by the chosen course of action. Sometimes, it is almost impossible to predict the various outcomes of a course of action, due to the unexpected consequences and the number of unknowns that are not accounted for in the benefit-cost analysis.

Management of Human Consumption and Impacts

Waste generation, measured in kilograms per person per day. The environmental impact of a community or humankind as a whole depends both on population and impact per person, which in turn depends in complex ways on what resources are being used, whether or not those resources are renewable, and the scale of the human activity relative to the carrying capacity of the ecosystems involved. Careful resource management can be applied at many scales, from economic sectors like agriculture, manufacturing and industry, to work organizations, the consumption patterns of households and individuals, and the resource demands of individual goods and services. The underlying driver of direct human impacts on the environment is human consumption. This impact is reduced by not only consuming less but also making the full cycle of production, use, and disposal more sustainable. Consumption of goods and services can be analyzed and managed at all scales through the chain of consumption, starting with the effects of individual lifestyle choices and spending patterns, through to the resource demands of specific goods and services, the impacts of economic sectors, through national economies to the global economy. Analysis of consumption patterns relates resource use to the environmental, social and economic impacts at the scale or context under investigation. The ideas of embodied resource use (the total resources needed to produce a product or service), resource intensity, and resource productivity are important tools for understanding the impacts of consumption. Key resource categories relating to human needs are food, energy, raw materials and water.

In 2010, the International Resource Panel published the first global scientific assessment on the impacts of consumption and production. The study found that the most critical impacts are related to ecosystem health, human health and resource depletion. From a production perspective, it found that fossilfuel combustion processes, agriculture and fisheries have the most important impacts. Meanwhile, from a final consumption perspective, it found that household. Consumption related to mobility, shelter, food, and energy-using products causes the majority of life-cycle impacts of consumption. According to the IPCC Fifth Assessment Report, human consumption, with current policy, by the year 2100 will be seven times bigger than in the year 2010.

Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services

In 2019, a summary for policymakers of the largest, most comprehensive study to date of biodiversity and ecosystem services was published by the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. It recommended that human civilization would need a transformative change, including sustainable agriculture, reductions in consumption and waste, fishing quotas and collaborative water management.

Technology

Before flue-gas desulfurization was installed, the air-polluting emissions from this power plant in New Mexico contained excessive amounts of sulfur dioxide. A sewage treatment plant that uses solar energy, located at Santuari de Lluc monastery, Majorca. One of the core concepts in sustainable development is that technology can be used to assist people to meet their developmental needs. Technology to meet these sustainable development needs is often referred to as appropriate technology, which is an ideological movement (and its manifestations) originally articulated as intermediate technology by the economist E. F. Schumacher in his influential work Small Is Beautiful and now covers a wide range of technologies. Both Schumacher and many modernday proponents of appropriate technology also emphasise the technology as people centered. Today appropriate technology is often developed using open-source principles, which have led to open-source appropriate technology (OSAT) and thus many of the plans of the technology can be freely found on the Internet. OSAT has been proposed as a new model of enabling innovation for sustainable development.

Business

The most broadly accepted criterion for corporate sustainability constitutes a firm’s efficient use of natural capital. This eco-efficiency is usually calculated as the economic value added by a firm in relation to its aggregated ecological impact. This idea has been popularized by the World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD) under the following definition: “Eco-efficiency is achieved by the delivery of competitively priced goods and services that satisfy human needs and bring quality of life, while progressively reducing ecological impacts and resource intensity throughout the life-cycle to a level at least in line with the earth’s carrying capacity” (DeSimone and Popoff, 1997: 47). Similar to the eco-efficiency concept but so far less explored is the second criterion for corporate sustainability. Socio-efficiency describes the relation between a firm’s value added and its social impact. Whereas, it can be assumed that most corporate impacts on the environment are negative (apart from rare exceptions such as the planting of trees) this is not true for social impacts. These can be either positive (e.g. corporate giving, creation of employment) or negative (e.g. work accidents, human rights abuses). Both eco-efficiency and socio-efficiency are concerned primarily with increasing economic sustainability. In this process they instrumentalize both natural and social capital aiming to benefit from win-win situations. Some point towards eco-effectiveness, socio-effectiveness, sufficiency, and eco-equity as four criteria that need to be met if sustainable development is to be reached.

Architecture and Construction

In sustainable architecture the recent movements of New Urbanism and New Classical architecture promote a sustainable approach towards construction that appreciates and develops smart growth, architectural tradition and classical design. This in contrast to modernist and International Style architecture, as well as opposing to solitary housing estates and suburban sprawl, with long commuting distances and large ecological footprints. The global design and construction industry is responsible for approximately 39 percent of greenhouse gas emissions. Green building practices that avoid emissions or capture the carbon already present in the environment, allow for reduced footprint of the construction industry, for example, use of hempcrete, cellulose fiber insulation, and landscaping [61-70].

Sustainable Development

Sustainable development is the overarching paradigm of the United Nations. The concept of sustainable development was described by the 1987 Bruntland Commission Report as “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.” There are four dimensions to sustainable development - society, environment, culture and economy - which are intertwined, not separate. Sustainability is a paradigm for thinking about the future in which environmental, societal and economic considerations are balanced in the pursuit of an improved quality of life. For example, a prosperous society relies on a healthy environment to provide food and resources, safe drinking water and clean air for its citizens. One might ask, what is the difference between sustainable development and sustainability? Sustainability is often thought of as a long-term goal (i.e. a more sustainable world), while sustainable development refers to the many processes and pathways to achieve it (e.g. sustainable agriculture and forestry, sustainable production and consumption, good government, research and technology transfer, education and training, etc.).

- Review Article

- Abstract

- Introduction

- What are the Sustainable Development Goals?

- What is the importance of sustainable development?

- What is development?

- What is a Developed Nation?

- What Is a Developing Country?

- Which Countries Have the Highest GDP per Capita?

- What Does HDI Mean?

- Advantages and Disadvantages of Renewable Energy

- Disadvantages of Renewable Energy

- References

What are the Sustainable Development Goals?

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), also known as the Global Goals, were adopted by the United Nations in 2015 as a universal call to action to end poverty, protect the planet, and ensure that by 2030 all people enjoy peace and prosperity. The 17 SDGs are integrated-they recognize that action in one area will affect outcomes in others, and that development must balance social, economic and environmental sustainability. Countries have committed to prioritize progress for those who’re furthest behind. The SDGs are designed to end poverty, hunger, AIDS, and discrimination against women and girls. The creativity, knowhow, technology and financial resources from all of society is necessary to achieve the SDGs in every context.

Goal 1

No Poverty

Eradicating poverty in all its forms remains one of the greatest challenges facing humanity. While the number of people living in extreme poverty dropped by more than half between 1990 and 2015, too many are still struggling for the most basic human needs. As of 2015, about 736 million people still lived on less than US$1.90 a day; many lack food, clean drinking water and sanitation. Rapid growth in countries such as China and India has lifted millions out of poverty, but progress has been uneven. Women are more likely to be poor than men because they have less paid work, education, and own less property. Progress has also been limited in other regions, such as South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, which account for 80 percent of those living in extreme poverty. New threats brought on by climate change, conflict and food insecurity, mean even more work is needed to bring people out of poverty. The SDGs are a bold commitment to finish what we started, and end poverty in all forms and dimensions by 2030. This involves targeting the most vulnerable, increasing basic resources and services, and supporting communities affected by conflict and climate-related disasters.

Goal 2

Zero Hunger

Unfortunately, extreme hunger and malnutrition remain a huge barrier to development in many countries. There are 821 million people estimated to be chronically undernourished as of 2017, often as a direct consequence of environmental degradation, drought and biodiversity loss. Over 90 million children under five are dangerously underweight. Undernourishment and severe food insecurity appear to be increasing in almost all regions of Africa, as well as in South America. The SDGs aim to end all forms of hunger and malnutrition by 2030, making sure all peopleespecially children-have sufficient and nutritious food all year. This involves promoting sustainable agricultural, supporting small-scale farmers and equal access to land, technology and markets. It also requires international cooperation to ensure investment in infrastructure and technology to improve agricultural productivity.

Goal 3

Good Health and Well-Being

We have made great progress against several leading causes of death and disease. Life expectancy has increased dramatically; infant and maternal mortality rates have declined, we’ve turned the tide on HIV and malaria deaths have halved. Good health is essential to sustainable development and the 2030 Agenda reflects the complexity and interconnectedness of the two. It takes into account widening economic and social inequalities, rapid urbanization, threats to the climate and the environment, the continuing burden of HIV and other infectious diseases, and emerging challenges such as noncommunicable diseases. Universal health coverage will be integral to achieving SDG, ending poverty and reducing inequalities. Emerging global health priorities not explicitly included in the SDGs, including antimicrobial resistance, also demand action. But the world is off-track to achieve the health-related SDGs. Progress has been uneven, both between and within countries. There’s a 31-year gap between the countries with the shortest and longest life expectancies. And while some countries have made impressive gains, national averages hide that many are being left behind. Multisectoral, rights-based and gender-sensitive approaches are essential to address inequalities and to build good health for all.

Goal 4

Quality Education

Since 2000, there has been enormous progress in achieving the target of universal primary education. The total enrollment rate in developing regions reached 91 percent in 2015, and the worldwide number of children out of school has dropped by almost half. There has also been a dramatic increase in literacy rates, and many more girls are in school than ever before. These are all remarkable successes. Since 2000, there has been enormous progress in achieving the target of universal primary education. The total enrollment rate in developing regions reached 91 percent in 2015, and the worldwide number of children out of school has dropped by almost half. There has also been a dramatic increase in literacy rates, and many more girls are in school than ever before. These are all remarkable successes. Progress has also been tough in some developing regions due to high levels of poverty, armed conflicts and other emergencies. In Western Asia and North Africa, ongoing armed conflict has seen an increase in the number of children out of school. This is a worrying trend. While Sub-Saharan Africa made the greatest progress in primary school enrollment among all developing regions - from 52 percent in 1990, up to 78 percent in 2012 - large disparities still remain. Children from the poorest households are up to four times more likely to be out of school than those of the richest households. Disparities between rural and urban areas also remain high. Achieving inclusive and quality education for all reaffirms the belief that education is one of the most powerful and proven vehicles for sustainable development. This goal ensures that all girls and boys complete free primary and secondary schooling by 2030. It also aims to provide equal access to affordable vocational training, to eliminate gender and wealth disparities, and achieve universal access to a quality higher education.

Goal 5

Gender Equality

Ending all discrimination against women and girls is not only a basic human right, it’s crucial for sustainable future; it’s proven that empowering women and girls helps economic growth and development. UNDP has made gender equality central to its work and we’ve seen remarkable progress in the past 20 years. There are more girls in school now compared to 15 years ago, and most regions have reached gender parity in primary education. But although there are more women than ever in the labor market, there are still large inequalities in some regions, with women systematically denied the same work rights as men. Sexual violence and exploitation, the unequal division of unpaid care and domestic work, and discrimination in public office all remain huge barriers. Climate change and disasters continue to have a disproportionate effect on women and children, as do conflict and migration. It is vital to give women equal rights land and property, sexual and reproductive health, and to technology and the internet. Today there are more women in public office than ever before, but encouraging more women leaders will help achieve greater gender equality.

Goal 6

Clean Water and Sanitation

Water scarcity affects more than 40 percent of people, an alarming figure that is projected to rise as temperatures do. Although 2.1 billion people have improved water sanitation since 1990, dwindling drinking water supplies are affecting every continent. More and more countries are experiencing water stress, and increasing drought and desertification is already worsening these trends. By 2050, it is projected that at least one in four people will suffer recurring water shortages. Safe and affordable drinking water for all by 2030 requires we invest in adequate infrastructure, provide sanitation facilities, and encourage hygiene. Protecting and restoring water-related ecosystems is essential. Ensuring universal safe and affordable drinking water involves reaching over 800 million people who lack basic services and improving accessibility and safety of services for over two billion. In 2015, 4.5 billion people lacked safely managed sanitation services (with adequately disposed or treated excreta) and 2.3 billion lacked even basic sanitation.

Goal 7

Affordable and Clean Energy

Between 2000 and 2018, the number of people with electricity increased from 78 to 90 percent, and the numbers without electricity dipped to 789 million. Yet as the population continues to grow, so will the demand for cheap energy, and an economy reliant on fossil fuels is creating drastic changes to our climate. Investing in solar, wind and thermal power, improving energy productivity, and ensuring energy for all is vital if we are to achieve SDG 7 by 2030. Expanding infrastructure and upgrading technology to provide clean and more efficient energy in all countries will encourage growth and help the environment.

Goal 8

Decent Work and Economic Growth

Over the past 25 years the number of workers living in extreme poverty has declined dramatically, despite the lasting impact of the 2008 economic crisis and global recession. In developing countries, the middle class now makes up more than 34 percent of total employment - a number that has almost tripled between 1991 and 2015. However, as the global economy continues to recover we are seeing slower growth, widening inequalities, and not enough jobs to keep up with a growing labor force. According to the International Labor Organization, more than 204 million people were unemployed in 2015. The SDGs promote sustained economic growth, higher levels of productivity and technological innovation. Encouraging entrepreneurship and job creation are key to this, as are effective measures to eradicate forced labor, slavery and human trafficking. With these targets in mind, the goal is to achieve full and productive employment, and decent work, for all women and men by 2030.

Goal 9

Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure

Investment in infrastructure and innovation are crucial drivers of economic growth and development. With over half the world population now living in cities, mass transport and renewable energy are becoming ever more important, as are the growth of new industries and information and communication technologies.

Technological progress is also key to finding lasting solutions to both economic and environmental challenges, such as providing new jobs and promoting energy efficiency. Promoting sustainable industries, and investing in scientific research and innovation, are all important ways to facilitate sustainable development. More than 4 billion people still do not have access to the Internet, and 90 percent are from the developing world. Bridging this digital divide is crucial to ensure equal access to information and knowledge, as well as foster innovation and entrepreneurship.

Goal 10

Reduced Inequalities

Income inequality is on the rise. The richest 10 percent have up to 40 percent of global income whereas the poorest 10 percent earn only between 2 to 7 percent. If we take into account population growth inequality in developing countries, inequality has increased by 11 percent. Income inequality has increased in nearly everywhere in recent decades, but at different speeds. It’s the lowest in Europe and highest in the Middle East. These widening disparities require sound policies to empower lower income earners, and promote economic inclusion of all regardless of sex, race or ethnicity. Income inequality requires global solutions. This involves improving the regulation and monitoring of financial markets and institutions, encouraging development assistance and foreign direct investment to regions where the need is greatest. Facilitating the safe migration and mobility of people is also key to bridging the widening divide.

Goal 11

Sustainable Cities and Communities

More than half of us live in cities. By 2050, two-thirds of all humanity -6.5 billion people- will be urban. Sustainable development cannot be achieved without significantly transforming the way we build and manage our urban spaces. The rapid growth of cities -a result of rising populations and increasing migration has led to a boom in mega-cities, especially in the developing world, and slums are becoming a more significant feature of urban life. Making cities sustainable means creating career and business opportunities, safe and affordable housing, and building resilient societies and economies. It involves investment in public transport, creating green public spaces, and improving urban planning and management in participatory and inclusive ways.

Goal 12

Responsible Consumption and Production

Achieving economic growth and sustainable development requires that we urgently reduce our ecological footprint by changing the way we produce and consume goods and resources. Agriculture is the biggest user of water worldwide, and irrigation now claims close to 70 percent of all freshwaters for human use. The efficient management of our shared natural resources, and the way we dispose of toxic waste and pollutants, are important targets to achieve this goal. Encouraging industries, businesses and consumers to recycle and reduce waste is equally important, as is supporting developing countries to move towards more sustainable patterns of consumption by 2030. A large share of the world population is still consuming far too little to meet even their basic needs. Halving the per capita of global food waste at the retailer and consumer levels is also important for creating more efficient production and supply chains. This can help with food security, and shift us towards a more resource efficient economy.

Goal 13

Climate Action

There is no country that is not experiencing the drastic effects of climate change. Greenhouse gas emissions are more than 50 percent higher than in 1990. Global warming is causing longlasting changes to our climate system, which threatens irreversible consequences if we do not act. The annual average economic losses from climate-related disasters are in the hundreds of billions of dollars. This is not to mention the human impact of geo-physical disasters, which are 91 percent climate-related, and which between 1998 and 2017 killed 1.3 million people and left 4.4 billion injured. The goal aims to mobilize US$100 billion annually by 2020 to address the needs of developing countries to both adapt to climate change and invest in low-carbon development. Supporting vulnerable regions will directly contribute not only to Goal 13 but also to the other SDGs. These actions must also go hand in hand with efforts to integrate disaster risk measures, sustainable natural resource management, and human security into national development strategies. It is still possible, with strong political will, increased investment, and using existing technology, to limit the increase in global mean temperature to two degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels, aiming at 1.5°C, but this requires urgent and ambitious collective action.

Goal 14

Life below Water

The world’s oceans - their temperature, chemistry, currents and life - drive global systems that make the Earth habitable for humankind. How we manage this vital resource is essential for humanity as a whole, and to counterbalance the effects of climate change. Over three billion people depend on marine and coastal biodiversity for their livelihoods. However, today we are seeing 30 percent of the world’s fish stocks overexploited, reaching below the level at which they can produce sustainable yields. Oceans also absorb about 30 percent of the carbon dioxide produced by humans, and we are seeing a 26 percent rise in ocean acidification since the beginning of the industrial revolution. Marine pollution, an overwhelming majority of which comes from land-based sources, is reaching alarming levels, with an average of 13,000 pieces of plastic litter to be found on every square kilometer of ocean. The SDGs aim to sustainably manage and protect marine and coastal ecosystems from pollution, as well as address the impacts of ocean acidification. Enhancing conservation and the sustainable use of ocean-based resources through international law will also help mitigate some of the challenges facing our oceans.

Goal 15

Life on Land

Human life depends on the earth as much as the ocean for our sustenance and livelihoods. Plant life provides 80 percent of the human diet, and we rely on agriculture as an important economic resources. Forests cover 30 percent of the Earth’s surface, provide vital habitats for millions of species, and important sources for clean air and water, as well as being crucial for combating climate change. Every year, 13 million hectares of forests are lost, while the persistent degradation of dry lands has led to the desertification of 3.6 billion hectares, disproportionately affecting poor communities. While 15 percent of land is protected, biodiversity is still at risk. Nearly 7,000 species of animals and plants have been illegally traded. Wildlife trafficking not only erodes biodiversity, but creates insecurity, fuels conflict, and feeds corruption. Urgent action must be taken to reduce the loss of natural habitats and biodiversity which are part of our common heritage and support global food and water security, climate change mitigation and adaptation, and peace and security.

Goal 16

Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions

We cannot hope for sustainable development without peace, stability, human rights and effective governance, based on the rule of law. Yet our world is increasingly divided. Some regions enjoy peace, security and prosperity, while others fall into seemingly endless cycles of conflict and violence. This is not inevitable and must be addressed. Armed violence and insecurity have a destructive impact on a country’s development, affecting economic growth, and often resulting in grievances that last for generations. Sexual violence, crime, exploitation and torture are also prevalent where there is conflict, or no rule of law, and countries must take measures to protect those who are most at risk The SDGs aim to significantly reduce all forms of violence, and work with governments and communities to end conflict and insecurity. Promoting the rule of law and human rights are key to this process, as is reducing the flow of illicit arms and strengthening the participation of developing countries in the institutions of global governance.

Goal 17

Partnerships for the Goals

The SDGs can only be realized with strong global partnerships and cooperation. Official Development Assistance remained steady but below target, at US$147 billion in 2017. While humanitarian crises brought on by conflict or natural disasters continue to demand more financial resources and aid. Many countries also require Official Development Assistance to encourage growth and trade. The world is more interconnected than ever. Improving access to technology and knowledge is an important way to share ideas and foster innovation. Coordinating policies to help developing countries manage their debt, as well as promoting investment for the least developed, is vital for sustainable growth and development. The goals aim to enhance North-South and South-South cooperation by supporting national plans to achieve all the targets. Promoting international trade, and helping developing countries increase their exports is all part of achieving a universal rules-based and equitable trading system that is fair and open and benefits all.

- Review Article

- Abstract

- Introduction

- What are the Sustainable Development Goals?

- What is the importance of sustainable development?

- What is development?

- What is a Developed Nation?

- What Is a Developing Country?

- Which Countries Have the Highest GDP per Capita?

- What Does HDI Mean?

- Advantages and Disadvantages of Renewable Energy

- Disadvantages of Renewable Energy

- References

What is the importance of sustainable development?