Brand Communication Through Sports Sponsorship. The Nature of Sponsorship in Elite European Football

Santiago Mayorga Escalada*

Director of the Master’s Degree in Digital Marketing. University lecturer and researcher, Universidad Isabel I, Spain

Submission: July 08, 2024; Published: July 29, 2024

*Corresponding author: Santiago Mayorga Escalada, Director of the Master’s Degree in Digital Marketing. University lecturer and researcher, Universidad Isabel I, Spain, Email: santiago.mayorga@ui1.es

How to cite this article: Santiago Mayorga Escalada*. Brand Communication Through Sports Sponsorship. The Nature of Sponsorship in Elite European Football. Rec Arch of J & Mass Commun. 2024; 1(3): 555561. 10.19080/RAJMC.2024.01.555561

Abstract

Professional football in Europe is a global advertising showcase. The objective of this research is to determine the typology of the brands that are official sponsors of the elite clubs of European professional football during the 22/23 season. The method is developed through a content analysis of the sponsoring brands of all the first division clubs of the five European leagues with the highest market value this season, in addition to those clubs that have been part of the Champions League (elite of European professional football). Sponsorship is a strategic brand communication action in itself. It is detected that the brands that are sponsors of the elite European football clubs come mostly from Asia, followed by Europe and America. Its activity is global and is mainly carried out in the banking, airlines and digital industry sectors. A large part of these brands are front companies for strategic government sectors that implicitly create territory marking for purely reputational purposes and to whiten their image in the international context through sport..

Keywords: Brands; Place branding; Sponsorship; Integral communications; Professional football; Clubs; Champions League; Sportswashing; Positioning; Reputation

Introduction

Approach

Historically, sport has been a place for social gatherings, attracting large masses of people to its activities. As a result of industrialization and the subsequent development of the information society, sport has become a powerful industry framed within showbusiness [1]. One of the most profitable activities within this sector is professional football, especially in Europe, due to its origin and thanks to its global expansion, as well as the massive penetration it has achieved in different markets across the five continents [2].

The consumption of sport, and especially of professional football, manages to bring together two types of audiences which, in addition to being massive, are characterized by their loyalty. Football fans construct a collective imaginary of a very strong identity type that manages to surpass the barriers of rationality [3]. In this sense, sportsmen and/or clubs are constituted as very powerful brands that have a captive and loyal public around all their identity and consumption tentacles [4].

Identitarianism, a phenomenon that starts and is transmitted from the depths of reasoning, is a drive that generates a very strong attachment within football through feelings of belonging [5]. The signifiers associated with football clubs, and which are an indissoluble part of their brand identity, have to do with emotions that go far beyond football and appeal to collectivism based on club, territorial, cultural, social, ideological, religious, etc. values.

Through sport, understood as an entertainment industry and, more specifically in the case of professional football, brands have also found a great showcase to reach mass audiences where they can develop different types of strategic communication actions, especially through sponsorship. The identity collectivism of football audiences is a very propitious magma for the association of a club’s brand image with commercial brands that seek to be impregnated with the values of the sport, and those projected by the sponsored clubs themselves [6]. The development of these commercial and advertising communication actions, which work deeply in the reputational sphere, have become a solid tool for visibility, positioning, recognition and identity for many brands with respect to their competitors.

Objectives

In accordance with the above, a series of objectives are established to structure this work.

• General objective: To determine the typology (origin and activity) of the brands that are official sponsors of the elite clubs of European professional football during the 2022/20223 season. In order to answer the general objective, it is necessary to outline a series of specific objectives to bring to light a series of relevant information that will make it possible to build a solid body of argument throughout the research in order to answer the general objective [7].

• Secondary objectives:

To identify which are the main European professional football leagues and which clubs comprise them.

To define which clubs are part of the European professional football elite during the 22/23 season.

To identify which are the main sponsoring brands of the clubs of the European professional football elite during the 22/23 season.

To analyze the origin, where they operate, and in which sector the activity in which the brands that are official sponsors of the clubs of the European football elite during the 22/23 season is inscribed.

After an initial review of articles with an impact on the object of study, this research is pertinent, original and relevant.

Theoretical framework

The approach and objectives of this research lead to the need to constitute a theoretical framework that lays the theoretical foundations for the subsequent empirical process. In this way, the concepts that form part of the object of study are established (identified, defined and delimited) and which will play the role of variables to be recorded in the research.

Branding (strategic brand management and communication)

The discipline in charge of aligning all the elements and actions that form part of the process for the strategic management of a brand is enormously complex. To this circumstance must be added the atavistic confusion that exists when approaching the phenomenon. This problem is reproduced, in turn, when it comes to identifying key elements that are an inseparable part of the process. Given this situation, a theoretical amalgamation will be carried out, based on the recognition of the main items of the discipline thanks to the bibliographical review of experts.

In order to delimit the concept of brand management from a holistic and integral strategic and multidisciplinary vision, thus avoiding endemic reductionisms, especially those centred on purely aesthetic issues, a vision shared by different authors is used: [8-19]. According to this integrating perspective of professional and academic experts, branding could be defined as a holistic process of an eminently strategic and multidisciplinary nature that, with a long-term purpose, manages to integrate and align all the decisions, actions and elements that shape the brand, connecting it with its audiences through a unique and relevant experience that gives it added value with respect to its competitors within the sector in which it operates.

The main elements that any branding process must comply with, and the main research teams that have analyzed them, are as follows:

• Holistic process of comprehensive strategic management [8,15].

• Specific professional scope [20].

• Adapting to the present, predicting the future [20,21].

• Unique positioning and generation of added value [11,22].

• Coherence, constancy and consistency [23,24].

• Brand architecture and portfolio management [25,26].

• Cyclical management process: analysis, construction, implementation and measurement [22,27,28].

It is as important to be aware of being a brand as it is to understand the concept of branding, in order to develop a professional, strategic and efficient process that is successful. This is particularly relevant in professional sport as a brand is the key player in the social, institutional and commercial relationship of a club. The positioning that a club manages to project, as well as the engagement it generates with its stakeholders, will create a certain value for the brand. In this way, it will be able to work on the generation of new business opportunities, including sponsorship (one of the main means of financing for clubs and professional sportsmen and women).

Place branding (territory and/or place branding)

Place branding, understood as the process of building and managing a brand associated with a territory, began to appear recurrently in the mid-1990s, but it was not until the beginning of the 21st century that it became a specific discipline.

The first variable to take into account when approaching the territory brand is to understand that, like any other agent susceptible of becoming a brand, it has a commercial intention:

“Designations of origin have recently become an instrument of undoubted economic power, as they can act as a catalyst for synergies, allowing production to be anchored to the territory, with the benefits that this entails” [29].

All this beyond the cultural and/or social dimensions that the identity of a territory brand may also contain.

Etymologically, Anglo-Saxon terminology does not fit with Spanish terminology. This issue makes it difficult to delimit the term territory. Jenkins [30] points out that the concept of space is used with connotations linked to a physical location, while the terms place and territory are used in relation to certain attributes. To bring together the concept of geographical space is one of the aspects on which the etymology surrounding the territory brand must work, taking into account the impossibility of being able to monopolise the identity and representativeness of an entire physical location [29].

Chias [31] indicates that, linked to the territory brand, is often the creation and development of a tourism brand that supports the creation of products and services related to it. The need to boost and promote tourism, with a clear positioning as opposed to differentiation from other similar offers, has led to the development of marketing strategies directly associated with territories [32,33].

The concept of territory branding can be conceived from two different points of view [34]: as a destination brand, which would refer only to the tourism sector, or as aplace brand, which has a broader and more holistic scope, including areas as diverse as tourism, investment, commercial, residential, cultural, urban, architectural, student, social, musical, gastronomic, iconic, etc. The aim of the place brand is to communicate the attractions of the territory, not only as a tourist place to visit, but also as an important centre for business and commerce, as well as an attractive and comfortable place to work, live, do business, enjoy its cultural offer, study, etc. [35].

In accordance with all these variables when defining the concept of place brand, it must be borne in mind that a territory can be delimited from purely physical coordinates to other essentially intangible attributes [32]. Territory, therefore, is not only a spatially limited phenomenon, but also has a discourse that generates meanings, which influences and organizes both the actions of visitors (external publics) and the conceptions of local residents [36].

Caligiuri and Baquero [37] understand that the territory brand expresses the set of values on which a differentiated promise is built, both internationally and within the territory itself. In short:

“The destination brand will try to bring together those characteristics that are specific to a geographical area and that best identify it and, above all, differentiate it from its surroundings. [This brand must be created by associating a set of values with a specific place, positioning it appropriately and generating positive emotional ties between the tourist and the destination. [...] The territory brand is more than just a destination brand, since it must serve to communicate benefits beyond the strictly tourist ones (business centre, study centre, commercial centre...) and to become a decisive factor in the social, cultural and economic development of a place” [33].

Territorial brands, through the different strategic actions that are generated within branding, form a robust relationship of interests that tends to lead to the management of multiple communicative intangibles of an advertising and promotional nature. Professional sport is one of the most attractive media platforms due to its profitability and efficiency, where the most powerful and global brands disembark to implement these integrated brand communications plans, especially through the activation of sports sponsorship [38].

Sports sponsorship

The concepts of sponsorship and patronage arise from the same action, which is based on providing aid to a person or organization in order to achieve an objective. The difference lies in the ultimate vocation of the sponsor towards the sponsored party. Paul Capriotti [39] points out that patronage has a philanthropic nature, whereas sponsorship has a commercial vocation. Since the 1960s, sponsorship activity has become one of the most powerful instruments used by organizations as part of their brand strategies, through marketing plans, public relations actions and commercial communication campaigns in order to connect with their potential audiences [40].

Sponsorship, understood as a concept on which there are multiple theoretical approaches, from different areas of knowledge, can be defined in a comprehensive way as:

“[...] a communication tool in which there is a provision of resources (economic, fiscal, physical, human) by one or more organisations (the sponsor(s)) to an individual or group, to one or more authorities or bodies (the sponsored), to enable the latter to pursue some activity in exchange for benefits contemplated in the sponsor’s strategy, and which can be expressed in terms of corporate, marketing, communication, social or human resources objectives” [41].

According to Torres and García [42]:

“[...] sponsorship is considered one of the most common formulas within commercial communication. The practice of sponsorship is directly linked to corporate social responsibility (Palencia, 2007), being a type of communication that combines the fulfilment of a social task with the search for commercial profitability in terms of brand image [39]. It is a regulated format (Vidal, 1997) which, far from losing intensity, has found its place without problem in the new digital context”. García-Contell [43] identifies, after an in-depth bibliographical review by experts, three main types of sponsorship: notoriety, image and credibility.

Within sponsorship, sports sponsorship tends to be the most common. Among the different concepts proposed by many researchers, one of the most classic proposals is Sleight’s [44], which already points to the definition of sports sponsorship as a business relationship between resource providers and sports activities or organizations. The former provide funds, resources or services and the latter guarantee part of the company’s rights to obtain commercial benefits in return. For Campos [45] sports sponsorship is “marketing to promote the sale to companies of the communicative values that sport can transmit”.

Huang Shuru [46] talks about the concept of sports sponsorship as a communication tactic that is carried out through the exchange of interests. Sponsoring companies provide funds and products and take on sports sponsorship as a tool to communicate with their customers. Companies provide sports sponsorship that can enhance their visibility, corporate image, sales results and other benefits. Lagae [47] understands sports sponsorship as:

“[...] any commercial arrangement whereby a sponsor contractually provides funding or other support for the purpose of establishing an association between the sponsor’s image, brand or products and ownership of a sponsorship, in return for the rights to promote this association and/or for securing certain agreed direct or indirect benefits”.

For Gómez [48] sports sponsorship is a:

“[...] contract by which a company or institution allocates economic resources (or bonuses in kind) to an activity of a sporting nature or to a team or individual athlete, the sponsoring entity’s brand or its messages disseminated throughout the competition in question, appearing on some elements necessary for its realisation through the media. Examples range from overprints on sports jerseys to the multimillion sponsorship contracts of Nike or Adidas with some sportsmen and women”.

Gallego Cantero [49] points out, by reviewing definitions given by different experts, that:

“[...] sports sponsorship involves an agreement between two parties in which one is a company or organisation that offers resources of various kinds to another that is related to sporting activity and that through the execution of its activity - with notable linkage to audiences - obtains in return revenues relating to image, promotion, brand value and others”.

It should be noted that Santos [50] distinguishes sports sponsorship from other types of sponsorship, based on four characteristics:

• Visibility. It tends to seek the greatest possible exposure of the logo or brand image to spectators.

• Audience. Aimed at the largest possible number of consumers, characterized by the captive interest in the sponsored event.

• Media presence. Media coverage of the event guarantees the appearance of the image with high exposure).

• Interdependence of the parties. Media and sports activities each pursue their own objectives.

Brands, especially the most powerful ones from different sectors, seek mass audiences and connect with their potential audiences. Sports brands (clubs, athletes, federations, competitions, events, etc.) have very strong identities, very loyal followers, and they have values as positive as those emanating from sport. Hence the growth of sponsorship brands, the boosting of activity and success in the efficiency of sports sponsorship.

The evolution of the consumer and the new objectives in company strategies have transformed the scenario and new trends can be observed with respect to sports sponsorship [51]. One of the most relevant changes in this respect has to do with the fact that the sponsoring company or brand has evolved from being a mere sponsor to actively recognizing itself as a partner or partnership of the sponsored brand. In this way, it moves from a tactical role (advertising support) to a strategic activity (brand building). In this new scenario, the concept of sponsorship activation has become an essential part of the promotion, return and revenue generation strategy of the sponsorship itself [52]. Moreover, sponsorship activation allows generating parallel activities and building unique engagement experiences with users, offering them added value through different contents of interest [53].

Materials and Methods

Any research process must have the appropriate methodological tools that guarantee its empirical development, as indicated by: (Sáenz, Gorjón, Quiroga, & Barrado, 2012); [54- 56]. For this process to be adequate and not to deviate from the object of study, delimited through the research objectives, a series of elements must be taken into account:

Premises

Study, analysis and presentation of the most relevant information to respond to the research objective (Sánchez Puentes, 2014); [57]. The object of study focuses on the concepts and variables identified in the main objective.

Agents and sample selection:

The empirical burden of the research method to be developed rests on the methodological tool of content analysis [58]. Through this method, the brands that are sponsors of the main professional football clubs in Europe during the 22/23 season are identified, and their typology (origin, where they operate and in which sector) will be studied. For this purpose, 100% of the clubs that form part of the top division of the five main European professional football leagues are chosen as a research sample, taking into account their market value [59]: Premier League (England), La Liga (Spain), Bundesliga (Germany), Serie A (Italy) and Ligue 1 (France). At the same time, and in order to segment in a more specific way the clubs that form the elite of European professional football, a variable is created within the content analysis where only the group of clubs that have played in the Champions League during the 22/23 season is recorded independently.

File

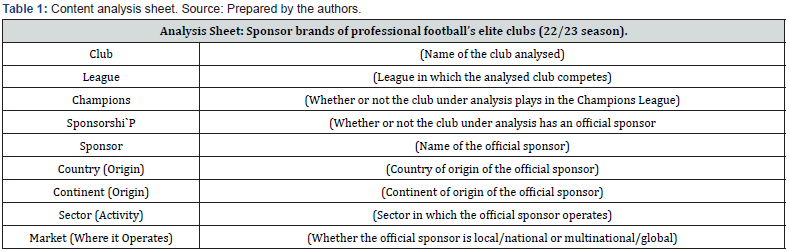

In the file used for the content analysis of each club, nine categories have been determined that are relevant to the achievement of the objectives proposed in this research:

• Club: Name of the club analyzed.

• League: National league competition to which the analyzed club belongs (in which it competes).

• Champions League: If the club analyzed has played in the top European competition during the 22/23 season.

• Sponsorship: Whether the club under analysis has an official sponsor during the 22/23 season.

• Sponsor: Sponsor brand of the club analyzed.

• Country: Country of origin (registration of the head office) to which the sponsoring brand belongs.

• Continent: Continent of origin (registration of the head office) to which the sponsoring brand belongs.

• Sector: Sector in which the activity in which the sponsoring brand operates is registered.

• Market/s (where it operates): Determines whether the sponsoring brand operates in the local/national market, or whether it operates in the multinational/global market.

The form used in the research to record the study of each club, within the content analysis process [60], is as follows (Table 1).

Criteria for analysis

A single, consistent criterion is used to determine the main sponsor of each club. The official uniforms (first uniform for registration and second uniform for confirmation of the data) of all the clubs under investigation are analyzed. In order to verify the information, the official websites of each of the clubs studied are also consulted. The official sponsor always appears on the chest of the shirts, at a larger size than the rest of the sponsors that may be on other parts of the uniform. On the official websites of the clubs, the sponsor appears prominently in the corporate section dedicated to this issue.

Quantitative and qualitative results

Once the analysis and registration of the clubs under study has been carried out, recording the relevant information in each of the study categories established in the analysis sheet, the methodological registration of the (quantitative) data is carried out using the SPSS programme. After recording the data, an analysis and cross-referencing of variables is carried out. This action leads to the emergence of a series of qualitative results that help to complete and enrich the quantitative data previously extracted [61,62]. It is not a sequential process, but a flexible and circular one:

“Analysis in qualitative research is a continuous process that begins with data collection. [...] notes are generated in which the analyst develops incipient ideas that will serve to give coherence to the data. [...] Qualitative analysis can be defined as the process of ordering, classifying, reducing and comparing in order to give meaning to the data obtained [61] (Ruiz Olabuénaga, 1999). Therefore, it is understood as the way in which the corpus of data will be manipulated, transformed, annotated and reflected upon” [63].

Results

A total of 96 European professional football clubs have been analyzed in this research, distributed across the national leagues in which they compete as follows:

• Premier League: 20 clubs (20.83%).

• La Liga: 20 clubs (20.83%).

• Bundesliga: 18 clubs (18.75%).

• Serie A: 20 clubs (20.83%).

• Ligue 1: 18 clubs (18.75%).

Of the total number of clubs analyzed, 18 of them (18.75%) also played in the Champions League during the 22/23 season. These clubs represent the elite of European professional football during that season.

In terms of official sponsors, the distribution by league is as follows:

• Premier League:

19 clubs (95%) have an official sponsor.

1 club (5%) has no official sponsor.

• La Liga:

20 clubs (100%) have official sponsors.

There are no clubs without an official sponsor.

• Bundesliga:

18 clubs (100%) have official sponsors.

There are no clubs without an official sponsor.

• Serie A:

20 clubs (100%) have official sponsors.

There are no clubs without an official sponsor.

• Ligue 1:

17 clubs (94.4%) have an official sponsor.

1 club (5.6%) has no official sponsor.

Of the 96 clubs analyzed, 94 clubs (97.9%) have an official sponsor, while 2 clubs (2.1%) do not have an official sponsor. 100% of the clubs playing in the Champions League (18 clubs that are the elite of European professional football) have official sponsors.

The research identifies a total of 24 countries of origin of the official sponsors of the analyzed clubs. In quantitative order, from the highest to the lowest number, they are: Germany (16), England (12), France (11), Italy (10), Spain (9), United States (8), United Arab Emirates (5), Hong Kong (3), Cyprus (2), Japan (2), Netherlands (2), Romania (2), Saudi Arabia (1), Brazil (1), China (1), Philippines (1), Indonesia (1), Isle of Man (1), Israel (1), Malta (1), Mexico (1), Qatar (1), South Africa (1) and Vietnam (1).

Divided by league, the results are as follows:

• Premier League: Official sponsors come from 14 countries. The most represented countries are England with 3 sponsors; and United Arab Emirates, Hong Kong and Cyprus with 2 sponsors, respectively.

• La Liga: It has 10 countries of origin of the sponsors. The most represented countries are Spain with 9 sponsors, England with 2, and the rest of the countries have only one sponsor of origin.

• Bundesliga: Sponsors come from only 3 different countries. Germany is the most numerous country (15 sponsors), followed by the United States (2 sponsors) and England (1 sponsor).

• Serie A: It has 7 countries of origin of the sponsors. The most represented countries are Italy with 9 sponsors, the United States with 4 sponsors and England with 3 sponsors.

• Ligue 1: It has 5 countries of origin of sponsors. France is the country with the most sponsors with 11, England has 3, and the rest of the countries have only one sponsor.

The Champions League clubs, i.e. those representing the elite of European professional football, have official sponsors from 8 different countries. In order, from highest to lowest, they are: United States (5 sponsors); United Arab Emirates and Hong Kong (3 sponsors); England and Germany (2 sponsors); Italy, Qatar and the Netherlands (1 sponsor).

By continent, the origin of the sponsors is distributed as follows: Europe has 67 sponsors (71.27%), Asia 16 sponsors (17.02%), America 10 sponsors (10.63%) and Africa 1 sponsor (1.06%). Oceania has no sponsors. Divided by league, the results are as follows for this variable:

• Premier League: It has sponsors from four continents. They are divided as follows: 9 sponsors aren from Europe (47.4%), 7 are from Asia (36.8%), 2 are from America (10.5%) and 1 is from Africa (5.3%).

• La Liga: It has sponsors from 3 continents with no sponsors from Africa or Oceania. The continental origin of the sponsors is divided as follows: 14 sponsors aren European (70%), 4 Asian (20%) and 2 are American (10%).

• Bundesliga: The German league has 16 European sponsors (88.9%) and 2 American sponsors (11.1%). This league has no Asian, African or Oceanic sponsors.

• Serie A: It has 13 European sponsors (65%), 4 American (20%) and 3 Asian (15%). The Italian league does not have any sponsors of African or Oceanic origin.

• Ligue 1: It has 15 European sponsors (88.2%) and 2 Asian sponsors (11.8%). It has no American, African or Oceanic sponsors.

The Champions League clubs, which represent the elite of European professional football, do not have any sponsors of African or Oceanic origin. Instead, they have sponsors from all other continents. They are distributed as follows: 7 sponsors are of Asian origin (38.9%), 6 European (33.3%) and 5 American (27.8%).

Within the analysis of the sector in which the sponsoring brands analyzed operate, a total of 10 major categories have been recorded: Banking (16 sponsors; 17%), Automotive (14 sponsors; 14.9%), Digital Industry (14 sponsors; 14.9%), Food/Distribution (11 sponsors; 11.7%), Services/Leisure (11 sponsors; 11.7%), Construction (10 sponsors; 10.6%), Gaming/Gambling (9 sponsors; 9.6%), Airlines (6 sponsors; 6.4%), Media Groups (2 sponsors; 2.1%) and Tourism (1 sponsor; 1.1%). Distributed around the five leagues analyzed, the following results are obtained:

• Premier League: It has 8 sponsors from Gaming/ Betting (42.1%); 4 sponsors from Banking (21.1%); 2 sponsors from Airlines (10.5%), Automotive (10.5%) and Digital Industry (10.5%); 1 sponsor from Services (5.3%); and no sponsors from Food/Distribution, Construction, Tourism, and Media Groups.• La Liga: It has 4 sponsors from Banking (20%), Digital Industry (20%) and Food/Distribution (20%); 3 sponsors from Construction (15%); 2 sponsors from Automobiles (10%); and 1 sponsor from Airlines (5%), Services (5%), and Tourism (5%). The Spanish league has no Gaming/Betting and Media Group sponsors.

• Bundesliga: It has 5 Digital Industry sponsors (27.8%); 4 Automotive sponsors (22.2%); 3 sponsors from Food/Distribution (16.7%), and Construction (16.7%); 2 sponsors from Services (11.1%); 1 sponsor from Banking (5.6%); and no sponsors from Airlines, Tourism, Gaming/Betting and Media Groups.

• Serie A: It has 5 Banking sponsors (25%); 4 Automotive sponsors (20%); 3 Digital Industry sponsors (15%); 2 Food/ Distribution sponsors (10%), Construction (10%) and Services (10%); 1 Airline sponsor (5%), and Media Groups (5%); and no Tourism and Gaming/Betting sponsors.

• Ligue 1: It has 5 Services sponsors (29.4%); 2 sponsors from Banking (11.8%), Automotive (11.8%), Food/Distribution (11.8%), Construction (11.8%), and Airlines (11.8%); 1 sponsor from Gaming/Betting (5.9%), and Media Groups (5.9%). The French league has no Digital Industry and Tourism sponsors.The sponsors of the clubs playing in the Champions League, representing the elite of European professional football, distribute their business activity by sector as follows: 4 sponsors from Banking (22.2%), Airlines (22.2%), and Digital Industry (22.2%); 2 sponsors from Services (11.1%), Automotive (11.1%), and Food/Distribution (11.1%). Within the Champions League clubs, there are no sponsors from Construction, Gaming/Betting, Media Groups and Tourism.

Finally, data is provided on the markets where the sponsors of the main European professional football clubs operate during the 22/23 season. The results show that: 65 sponsoring brands operate in global/multinational markets (69.1%); while 29 sponsoring brands operate locally/nationally (30.9%). Divided by league, the results for this variable are as follows:

• Premier League: All 19 club sponsorship brands in the English Premier League in the 22/23 season operate on a global/ multinational basis (100%).

• La Liga: There are 16 clubs that have sponsorship brands whose operational nature in the markets is global/multinational (80%); while there are 4 sponsors that operate on a local/national basis (20%).

• Bundesliga: There are 12 clubs that have sponsoring brands that operate globally/multinationally (66.7%); compared to 6 clubs that have sponsoring brands that operate in the local/ national market (33.3%).

• Serie A: It has 11 sponsoring brands operating on a global/multinational basis (55%); compared to 9 sponsoring brands operating in local/national markets (45%).

• Ligue 1: It registers 7 sponsoring brands operating globally/multinationally (41.2%); while the remaining 10 sponsors operate in local/national markets (58.8%).

The clubs playing in the Champions League during the 22/23 season, and therefore representing the elite of European professional football, have 17 sponsors operating in global/ multinational markets (94.4%), compared to 1 sponsor operating in the local/national market (5.6%).

Discussion

Beyond Transfermarkt’s report on the five most valuable European leagues in professional football during the 22/23 season, the Annual Review of Football Finance published by the consultancy firm Deliotte [64] indicates that the Premier League is worth more than 6.7 billion euros in revenue, compared to around 4 billion euros for both La Liga and the Bundesliga. The German league is experiencing exponential growth in recent years. Italy’s Serie A is in the 2.4 billion euro range, and France’s Ligue 1 is around 1.8 billion euros. The five big leagues of professional football in Europe have achieved a record revenue of more than 18.6 billion euros in the 22/23 season [65].

Both the revenues and the market value achieved by the professional football leagues in Europe are a spur for the big global brands when making their sponsorship decisions. The figures, along with the value of sponsorships, skyrocket in the field of the top continental competition, the Champions League [66]. To these circumstances we must multiply the reputational, media and commercial issue. The communication channels and the impact on audiences make this type of club an object of desire for sponsoring brands [67].

All clubs competing in the top division of the five major European professional football leagues during the 22/23 season have sponsors, except in two particular cases. One of the clubs without an official sponsor had legal problems with the contract of its previous sponsor brand. The other club took the decision to change its corporate policy not to have an official sponsor on its shirt. In other words, 100% of the analyzed clubs could have an official sponsor. This underlines the attractiveness (profitability, efficiency, reputation and value) for brands to sponsor Europe’s top professional football clubs.

Club sponsorships tend to follow more or less stable patterns. In any case, it is worth noting the importance of the casuistry of the different national leagues. There is a strong influence of the market value of the national league itself, its international projection; even the development of the country’s industrial fabric, the strength of the community/territorial identity ties that can be activated in local/national cases with various brands, and the league’s own regulations regarding the possible use or restriction of companies related to gambling and betting [68].

In the five most valuable leagues in European professional football, the majority of brands that sponsor clubs are local/ national in origin. This would have to do with the fact that many of the clubs in these leagues find more modest and/or local sponsors, where the identitarianism and collectivism around the clubs is very strong [3]. Many of these sponsors use the national/ local power of the clubs as ambassadors of place/territory to also attach themselves to a particular community/collectivity. On the other hand, it is very likely in many cases that these sponsoring brands do not have the capacity to activate a sponsorship of a larger club; and in other cases they may not be interested because of the identity/community affinity in the brand’s attachment to the specific place where it operates and/or originates. Another key circumstance that can condition the logic of sponsorship in European professional football is the national/local idiosyncrasy: political, economic, social, cultural, religious, etc. (beyond the development of the industrial fabric, as previously mentioned).

The markets in which the main sponsors of European professional football clubs operate are, for the most part, multinational/global in nature. Admittedly, this logic is topdown in terms of the market value of each league analyzed. The Premier League is the European professional football league with the highest market value, with 100% of its sponsors operating in global/multinational markets. Ligue 1 is the league with the lowest market value among the five strongest European professional football leagues, with 41.2% of sponsors operating/performing in global/multinational markets.

The performance of Europe’s elite football clubs, i.e. those playing in the Champions League, varies from the patterns of the national leagues. 100% of these clubs have official sponsors during the 22/23 season. The sponsors belong to a total of 8 different countries, with the most sponsorships: United States, United Arab Emirates and Hong Kong. These sponsors come mainly from Asia, followed by Europe and America. There are no sponsors of African or Oceanic origin. They are mostly active in the banking, airline and digital industries.

The companies that sponsor the top European football clubs operate mostly in global markets, i.e. they are multinational companies. Within this group of sponsoring brands, the majority are of non-European origin:

• Sponsor brands of North American origin: They seek to reinforce their commercial activity, positioning and brand visibility on a global level within a very powerful sector in economic, media and reputational terms (with a great capacity to open up new markets on the five continents). This type of sponsorship enhances the value and competitive capacity of the brands.

• Sponsor brands of Asian origin: Companies from strategic government sectors that seek to position the brand of that country (place branding) in an implicit way and with a reputational purpose; enhancing the whitening of its image in the international context through sport [69]. This practice is also known as sportswashing [70] and is described as follows:

“In the case of sportswashing, the way attention is routed away from the moral violation is through sport. Because sport engages the passions of so many people and because sport commands a huge amount of attention, it has become a valuable strategic vehicle for navigating the fundamental dynamic between a moral violation and the desire for that violation not to be attended to by others” [71].

In the European football elite there are also cases of European sponsoring brands that are a national symbol in their country (territorial brand with a strong local/national identity) and at the same time perfectly recognized on a global/multinational level (global reputation and positioning) thanks to their business/ commercial activity. There is only one club in the European football elite (Champions League) whose sponsor operates/acts in local/national type markets. This club does not belong to any of the five European professional football leagues with the highest market value, which may explain this.

The discussion of results for the present work also generates two perspectives related to the deepening of the object of study and the advancement of knowledge on the subject treated throughout the previous points:

• Prospective: It is considered that the line of research opened up by this work has a long way to go in the future. Once the methodological file for the content analysis has been validated, there are multiple fields of sponsorship that exist in professional sport beyond football. This would also generate the possibility of being able to compare the results with those of this article.

• Limitation: The positive burden of developing work that is pertinent, original and relevant also has certain limiting connotations. In this case, two main ones have been detected: there was no validated methodological file for the content analysis (one had to be constructed ad hoc through the statement of objectives and the development of the theoretical framework) and there was no scientific production on the object of study to be able to compare and discuss the results (all the bibliography consulted on the subject dealt with the typology of sports sponsorship, case studies, etc., but in no case were studies found on the typology of the brands that sponsor the football clubs that form part of the European football elite).

Conclusion

According to the results obtained throughout the development of this research, a solid body of arguments is formed that allows us to give a relevant response, in an inverse staggered manner -from secondary to general-, to each of the objectives designed at the beginning of the process. Following the economic, budgetary and investment value reports produced by Transfermarkt and Deloitte, it is concluded that the five most relevant professional football leagues in Europe are the Premier League (England, 20 clubs in its first division), La Liga (Spain, 20 clubs in its first division), the Bundesliga (Germany, 18 clubs in its first division), Serie A (Italy, 20 clubs in its first division) and Ligue 1 (France, 20 clubs in its first division).

The Champions League is the competition that brings together the champions of all professional European leagues, plus the top 3 to 5 ranked clubs from the five most important professional leagues on the continent. In addition, this competition is the one with the highest economic value, investment, budget and distribution of money for clubs in European professional football. Therefore, the clubs that win the right to play in this competition each season become the elite of European professional football.

All clubs in the elite of European football have an official brand sponsor. The origin of these sponsors amounts to 8 countries, with the USA providing the most sponsoring brands, followed by the United Arab Emirates and Hong Kong. In the third tier are England and Germany; and in the fourth tier are Italy, Qatar and the Netherlands. The largest continental origin of the sponsors of European football’s elite is Asia, followed by Europe and America. There are no sponsors of African or Oceanic origin.

These sponsoring brands are mostly active in the banking, airline and digital industries. Moreover, these brands operate almost entirely in global markets, i.e. they are large multinational companies. Within this group of sponsoring brands, the majority are of non-European origin:

• North American: global reinforcement of their positioning, increased visibility, greater competitiveness and opening up to new markets.

• Asian: belonging to strategic governmental sectors that brand the territory of countries that are not democracies and/or are denounced for violating human rights. These sponsorships seek to enhance the reputational whitening of the image of these countries in the international context through sport (sportswashing).

In the European football elite, there are also cases of European sponsoring brands that are a national symbol in their country (identity and attachment to the community) and that, at the same time, are perfectly recognized at a global/multinational level (reputation and international positioning) thanks to their business/commercial activity. There is only one club in the European football elite whose sponsor operates/acts in local/ national type markets. This club does not belong to any of the five European professional football leagues with the highest market value, which may explain this.

In general terms, it can be indicated that there are four main groups of sponsoring brands within European professional football, divided according to their strategic reputational interests by origin and by activity/operationality:

• Sponsor brands with a local/national scope: Sponsors that are attached to the identity of the clubs and the territory they represent, in order to form an association of specifically local attributes that may go beyond football (community, cultural, social, political, religious, etc.).

• European brands of national origin and global projection: European sponsors that are sector leaders in their respective countries, with a very strong local identity attachment that, in addition, enjoy a great global reputational projection (or are in the process of internationalization).

• Non-European global/multinational brands: Multinational sponsors that, without being of European origin, seek to reinforce their activity, positioning, reputation and visibility; also seeking to break into new markets thanks to the great capacity for international media penetration, across the five continents, that elite European professional football has.

State brands (Asian origin): Global/multinational sponsors that are usually governmental companies operating in strategic sectors and implicitly brand countries that are not democracies and/or do not comply with human rights. The purpose of these sponsorships is purely reputational and to whiten their image in the international context through sport (sportswashing). This type of brand, especially those associated with Qatar and the United Arab Emirates, stand out as official sponsors of the top clubs of the European professional football elite [72-74].

References

- Panzeri D (2020) Fútbol: dinámica de lo impensado. Capitán Swing Libros.

- Cayuela DM (2023) Análisis de escenarios eficientes en la industria del fútbol. Tesis doctoral. Universidad de Málaga, Spain.

- Llopis Goig R (2020) Deporte e identidad nacional: articulaciones y desconexiones en contextos postnacionales. Papeles del CEIC 1: 1-13.

- Ramos P (2022) Marketing en el Fú Importancia de las marcas en la industria futbolística. Trabajo de Fin de Grado. Universidad de Valladolid, Spain.

- Álvarez JDA (2022) El fútbol en función de la identidad y el nacionalismo. Un estado de arte (1991-2018). Quiró Revista de Estudiantes de Historia 8(16): 28-43.

- Lobillo G, Cancelo M (2017) La presencia de las marcas en el futbol. El caso de España y México. Razón y Palabra 21(97): 552-565.

- Silverman D (1997) Qualitative research. Theory, method and prectice. SAGE.

- Aaker D, Joachimsthaler E, Del Blanco R, Fons V (2005) Liderazgo de marca. Deusto, Bilbao, Spain.

- Gil J (2010) Branding. Tendencias y retos en la comunicación de marca. Barcelona: Editorial UOC.

- Velilla J (2010) Branding: Tendencias y retos en la comunicación de marca. Barcelona: UOC.

- Keller K, Parameswaran M, Jacob I (2011) Strategic brand management: Building, measuring and managing brand equity. Pearson Education.

- Costa J (2013) Los 5 pilares del branding. CPC Editor.

- Aebrand (2014) La salud del branding en España. Informe de resultados 2014. Madrid: AEBRAND & ESADE.

- Cerviño J, Baena V (2014) Nuevas dimensiones y problemáticas en el ámbito de la creación y gestión de marcas. Cuadernos de estudios empresariales 24: 11-50.

- Elliott RH, Rosenbaum-Elliott R, Percy L, Pervan S (2015) Strategic brand management. Oxford University Press, USA.

- Ayestarán E (2016) El Imperativo Digital: la gestión empresarial de la era digital. Boletín de estudios económicos 71(219): 457-482.

- Benbunan J, Schreier G, Knapp B (2019) Disruptive Branding: How to Win inTimes of Change. Londres: Kogan Page.

- Llorens C (2019) La creación del logotipo España Global. Gráffica, Slovakia.

- Mayorga S (2020) Relevancia de la gestión de marcas dentro de los grados de publicidad, comunicación publicitaria, corporativa, y marketing en la universidad españ Ediciones Universidad de Salamanca. Fonseca, J Communication 20: 91-124.

- Stalman A (2014) Brandoffon: el branding del futuro. Gestión 2000.

- Benavides J (2013) A propósito del brand management. En: Principios de estrategia publicitaria y gestión de marcas. Nuevas tendencias de brand management. Madrid: McGraw-Hill pp. 9-12.

- Aaker D (2012) Relevancia de la marca. Pearson Educación, Madrid, Spain.

- Frampton J (2010) ¿Qué hace grande a una marca? En: En clave de marcas. Madrid: LID pp. 79-87.

- Walvis T (2010) Branding with brains. The science of setting sustomers to shoose your company. Pearson.

- García M (2005) Arquitectura de marcas. Esic Editorial, Madrid, Spain.

- Kapferer JN (2012) The new strategic brand management. Advance insights & strategic thinking. Kogan Page.

- Bjerre M, Heding T, Knudtzen C (2020) Brand management: Mastering research, theory and practice. Routledge, London, UK.

- Keller K, Brexendorf T (2019) Strategic Brand Management Process. Handbuch Markenführung, Wiesbaden: Springer Gabler pp. 155-175.

- Cruz E, Ruiz E, Zamarreño G (2017) Marca territorio y marca ciudad, utilidad en el ámbito del turismo. El caso de Málaga. Int J Scientif Manage Tourism 3(2): 155-174.

- Jenkins R (2005) Globalization, Corporate, Social Responsability and poverty. International Affairs 81/3: 525-550.

- Chias J (2004) El negocio de la felicidad: Desarrollo y marketing turístico de países, regiones, ciudades y lugares. Prentice Hall, Madrid, Spain.

- Kotler P, Gertner D (2002) Country as Brand, Product, and Beyond: A Place Marketing and Brand Management Perspective. J Brand Manag 9: 249-261.

- González Oñate C, Martínez Bueno S (2013) La marca territorio como elemento de la comunicación: Factor estratégico del desarrollo turístico en Cuenca. Pensar la Publicidad 7(1): 113-134.

- Huertas A (2011) Las claves del citybranding. Portal de la Comunicación InCom-UAB, Consultado el 15/12/2022.

- Alameda D, Fernández E (2012) La comunicación de las marcas territorio. En: Actas del IV Congreso Internacional Latina de Comunicación Social.

- Govers R, Go F (2009) Place Branding: Glocal, Virtual and Physical Identities, Constructed, Imagined and Experienced. Palgrave Macmillan, Reino Unido, Europe, UK.

- Caligiuri FJ, Baquero CG (2019) La maca territorio o la mundualización de lo nuestro. Estudios Institucionales 6(10): 211-226.

- Blay R, Benlloch MT, Sanahuja G (2020) Marca, Territorio Y Deporte: Un Triángulo Estratégico en la Gestión de Intangibles Comunicativos. Tirant Lo Blanch.

- Capriotti P (2007) El patrocinio como expresión de la responsabilidad social corporativa de una organizació Razón y palabra (56).

- Walraven M, Koning R, Bijmolt T, Los B (2016) Benchmarking sports sponsorship performance: efficiency assessment with data envelopment analysis. J Sport Manag 30(4): 411-426.

- Barreda R (2009) Eficacia de la transmisión de la imagen en el patrocinio deportivo: una aplicación experimental. Tesis Doctoral. Departamento de Administración de Empresas y Marketing. Universitat Jaume I.

- Torres E, García S (2020) Patrocinio deportivo femenino. Situación actual y tendencias. Comunicación y Género 3(2): 125-137

- García-Contell P (2017) El patrocinio deportivo en el sector asegurador. Trabajo de Fin de Má Máster Universitario en Nuevas Tendencias y Procesos de Innovación en Comunicación. Dirección Estratégica de la Comunicación. Universitat Jaume I.

- Sleight S (1989) Sponsorship: What it is and how to use it. Maidenhead Berkshire. McGraw-Hill.

- Campos C (1997) Marketing y patrocinio deportivo. Colección Gestión Deportiva. GPE

- Huang S (1999) Research on the management of professional sports sponsorship in Taiwan á Institute of Business Management. National Chiao Tung University, Taiwan.

- Lagae W (2005) Sports Sponsorship and Marketing Communications: A European Perspective. Pearson Education.

- Gómez Nieto B (2017) Fundamentos de la Publicidad. ESIC.

- Gallego P (2021) Efectividad de la comunicación de la marca de las entidades financieras al consumidor a través del patrocinio deportivo. Tesis doctoral. Programa de Doctorado en Investigación en Medios de Comunicación por la Universidad Carlos III de Madrid.

- Santos LF (2013) Responsabilidad Social Corporativa en el Patrocinio Deportivo. Historia y Comunicación Social 18: 255-265.

- Sanahuja G, Martínez P, López L (2021) El post-patrocinio deportivo en la era post-pandemia. Deporte y comunicación: una mirada al fenómeno deportivo desde las ciencias de la comunicación en Españ Tirant Lo Blanch pp. 209-252.

- Beltrán S (2016) La Evolución del patrocinio en el fútbol: los casos de los equipamientos de los clubes de primera división en la Liga de Fútbol Profesional de España y de la Premier League Inglesa desde la temporada 2000-2001 hasta la temporada 2015-2016. Tesis doctoral. Universitat Jaume I.

- Franch E, Sanahuja G, Mut M, Campos C (2019) Inversión y evaluación del patrocinio deportivo en Españ Revista Internacional de Relaciones Públicas 9(17): 139-164.

- Hernández Sampieri R (2006) Formulación de hipó En: Metodología de la investigación. McGraw-Hill pp. 73-101.

- Herrera E (2008) Metodología de la investigació Pearson-Prentice Hall, US.

- Krueger R (1991) El grupo de discusión: guía práctica para la investigación aplicada. Pirá

- Taylor S, Bogdan R, DeVault M (2015) Introduction to qualitative research methods: A guidebook and resource. John Wiley & Sons.

- Piñuel Raigada JL (2002) Epistemología, metodología y técnicas del análisis de contenido. Sociolinguistic Studies 3(1): 1-42.

- Transfermarkt (2023) Clasificación de las ligas de futbol europeas en función de su valor de mercado.

- Vargas Cordero Z (2009) La investigación aplicada: una forma de conocer las realidades con evidencia cientí Revista Educación 33(1): 155-165.

- Rodríguez Bravo Á (2003) La Investigación aplicada. Anàlisi: Quaderns de comunicació i cultura 30: 17-36.

- Weber M (2017) Methodology of social sciences. Routledge, US.

- Sanz J (2013) Guía práctica 8. La metodología cualitativa en la evaluación de políticas pú Colección Ivàlua de guías prácticas sobre evaluación de políticas públicas. Cevagraf, Spain.

- Deloitte (2023) Annual Review of Football Finance 2023

- Cinco Días (2022) Las cinco grandes ligas de fútbol ingresarán un récord de 18.600 millones esta temporada.

- TyC Sports (2022) UEFA Champions League 2022-23: cuánto ganará cada equipo.

- Ramchandani G, Plumley D, Mondal S, Millar R, Wilson R (2023) You can look, but don’t touch’: competitive balance and dominance in the UEFA Champions League. Soccer & Society 24(4): 479-491.

- Legal Sport (2023) La Premier League da un paso vital contra las apuestas deportivas. Noticia de redacció Link: La Premier League da un paso vital contra las apuestas deportivas (legalsport.net).

- Camuñas A (2022) Geopolítica del futbol: historia, razones e impactos de la penetración árabe en el deporte occidental. Trabajo de Fin de Grado. Facultad de Ciencias Humanas y Sociales. Universidad Pontificia de Comillas, Spain.

- Romera A (2022) Las prácticas de sportswashing en el fú Trabajo de Fin de Grado. Departamento de Administración de Empresas y Comercialización e Investigación de Mercados (Marketing). Universidad de Sevilla, Spain.

- Fruh K, Archer A, Wojtowicz J (2023) Sportswashing: Complicity and Corruption. Sport, Ethics and Philosophy 17(1): 101-118.

- Solano Santos LF (2013) Responsabilidad Social Corporativa en el Patrocinio Deportivo. Historia y Comunicación Social 18: 255-265.

- Nogueira L, Nogueira M, Navarro J, Lizcano E (2015) Metodología de las ciencias sociales. Tecnos.

- Puentes RS (2000) Enseñar a investigar: una didáctica nueva de la investigación en ciencias sociales y humanas. Plaza y Valdés, Spain.