A Systematic Review of the Evidence for Intramedullary Hindfoot Nailing in Elderly Patients with Unstable Ankle Fractures

Grazette A1, El Gamal T2 and Nikolaides AP2*

1 PGCertMedEd University Hospitals Coventry and Warwickshire NHS Trust Coventry, UK

2 Birmingham Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust - Birmingham UK

Submission: September 09, 2018;Published: September 21, 2018

*Corresponding author: Nikolaides AP, Senior Orthopaedic and Trauma Specialist Heartlands Hospital University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust Birmingham UK & Hon Senior Lecturer University of Birmingham, UK.

How to cite this article: Grazette A, El Gamal T, Nikolaides AP. A Systematic Review of the Evidence for Intramedullary Hindfoot Nailing in Elderly Patients with Unstable Ankle Fractures. Ortho & Rheum Open Access J 2018; 12(5): 555850. DOI: 10.19080/OROAJ.2018.12.555850.

Introduction

Rationale

Ankle fractures are a common orthopaedic injury accounting for 9% of fractures [1]. As with the majority of trauma, there is a bimodal distribution of incidence with peaks in young males and elderly females [2]. Treatment principles are to hold the ankle in a reduced position for long enough to allow bony union. If this can’t be adequately achieved with a plaster then surgical intervention is routinely undertaken and traditionally achieved with plate osteosynthesis. However, as the average age of the population increases, fragility fractures are becoming more common. Fragility fractures are those resulting from low level trauma, which would not usually be expected to cause a fracture [3]. They are often seen in elderly patients with multiple medical co-morbidities and impaired mobility and can be complicated by poor soft tissues surrounding the fracture. These injuries pose new challenges to surgeons. Both plaster immobilisation and traditional plate osteosynthesis both have numerous potential complications including wound breakdown, metalwork failure and non- or mal-union [4].

Restricting weight bearing in any patient group is difficult [5]. In clinical practice this often results in elderly patient’s weight bearing as required or not mobilising at all. Prolonged immobility can lead to worsening of medical co-morbidities and a loss of mobility, function and independence [6]. There is now a trend towards the use of load-sharing or load-bearing devices in the treatment of osteoperotic fractures of the femur to allow immediate weight bearing and minimise this loss of function associated with prolonged periods of immobility [7].

The elderly patient with an unstable ankle fracture is a common case presentation at trauma meetings around the country. It has been my experience that some surgeons have opted for intramedullary (IM) fixation with a retrograde calcaneo-talo-tibial nail for the management of frail, elderly patients with restricted mobility, on the rationale that it allows immediate full weight bearing and easy management of the soft tissue envelope.

Research Objectives

The aim of this systematic review is to identify the evidence on hindfoot IM nailing in elderly patients with fragility fractures of the ankle by means of a structured database search. Studies will be identified following the application of strict inclusion and exclusion criteria prior to critical appraisal based on recognised appraisal methodology.

Methods

Eligibility Criteria (Inclusion & Exclusion criteria)

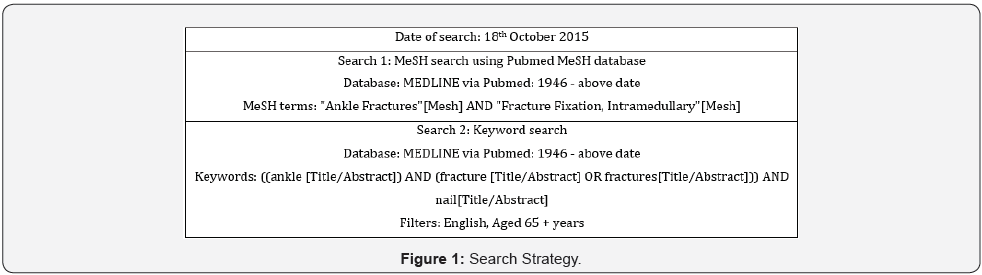

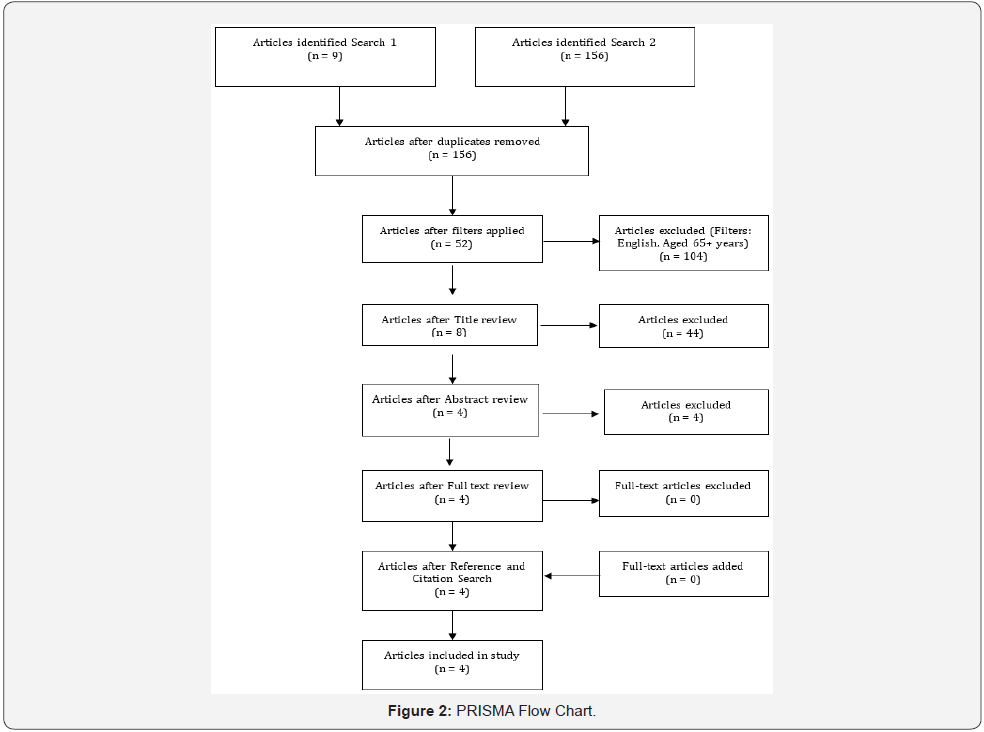

Primary research studies evaluating hindfoot (calcaneotalotibial or tibiotalocalcaneal) IM nailing of ankle fractures in patients 65 years and older as a primary procedure were included in the systematic review, which was conducted with the aid of The PRISMA Statement [8]. Articles in which the text was not English language were excluded. Information Sources, Search Strategy, Study Selection & Data Extraction. An electronic Pubmed search of the MEDLINE database was conducted for relevant studies (Figure 1). Two search strategies were adopted, one using MeSH terms and one using a keyword search. These search strategies are documented in Table 1. Following the application of filters for inclusion and exclusion criteria, the titles of all returned papers were screened by a single author (AG). If an article appeared to meet inclusion criteria, then the abstract was screened. Full text of the articles deemed eligible were then read to confirm applicability for review. Finally reference and citation tracking of these articles was performed to ensure no relevant articles were missed (Figure 2). Data was extracted from each article on an individual basis by the single author, AG.

Quality Analysis & Critical Appraisal

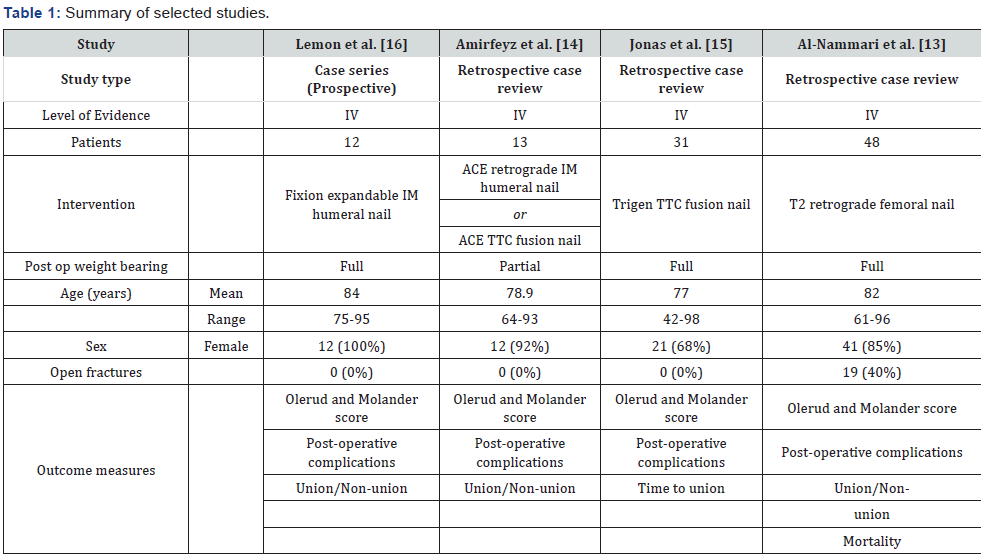

Each of the final articles were thoroughly read and categorised by study type. The studies were labelled with one of 5 levels of evidence, from I to V, with I being the highest [9]. Each study was reviewed for number of participants, intervention type, patient age and basic demographics and the outcome measures used (Table 1). Furthermore, each study’s research question and methodology were summarised by means of a PICO (patient or problem, intervention, comparison and outcome) strategy. The studies were critically appraised with the aid of the PRISMA checklist [8] and a methodological index for non-randomised studies [10]. Risk of bias was assessed at an individual study level as no randomised trials were included in the review. This was performed with the assistance of the RoBANS (Risk-of-Bias Assessment tool for Nonrandomized Studies) [11].

Results

The initial searches yielded 156 articles. 2 different search strategies were used, one using MeSH headings and one using a Keyword search of Titles and Abstracts. The MeSH search retrieved 9 articles all of which were duplicates to those retrieved from the Keyword search. Following application of filters to the keyword search, 52 articles were identified. Review of the titles and, where clarification was necessary, the abstracts with application of inclusion criteria identified 4 articles for review [12-15]. The full texts were read, and all met inclusion and exclusion criteria. Review of the references and citations of these 4 articles identified no further articles for inclusion (Figure 1). All 4 articles were classified as type IV evidence [9] and included 3 retrospective case reviews [12-14], and 1 prospective case series [15].

Lemon et al. [15]

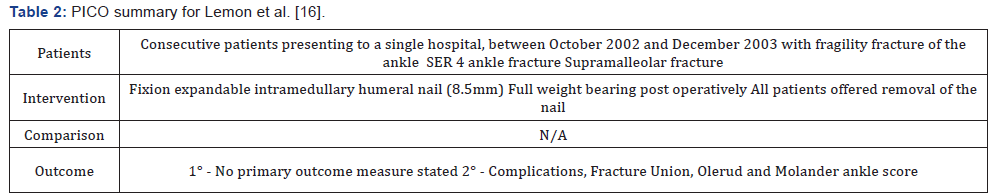

This study is the first to report the use of an expandable nail for the stabilisation of fragility fractures of the ankle. The aims of the study are not directly stated, but it looks at the feasibility of using this technique in a population where both operative and non-operative interventions have a high complication risk. It is written as a prospective case series, although this is not directly stated and there is no mention of an a priori protocol. No primary outcome measure is stated, but they report a patient reported outcome score as well as observed clinical complications (Table 2).

The study reports 12 consecutive patients from a single hospital, recruited over a clearly defined 14-month period and all treated with the same intervention. The inclusion criterion was a patient with a fragility fracture of the ankle. Fragility fracture is not further defined. They have defined included fractures as being either Lauge-Hansen [16] supination eversion stage 4 (SE 4) with 2mm of talar shift or supramalleolar of both tibia and fibula with greater than 15 degrees of angulation on at least one view. There were no exclusion criteria listed. The failure to define fragility fracture raises the possibility of missing the inclusion of or inappropriately excluding patients and puts the study at risk of selection bias. The fact that this single hospital had only 12 cases over a 14-month period further raises concerns of recruitment and selection bias. The inclusion of supramalleolar fractures in this study also warrants scrutiny as they are not classified as an ankle fracture according to the OTA/ AO classification [17]. Selection bias is an inherent problem of case series, and the reporting of a consecutive series has attempted to reduce this.

The intervention was a Fixion IM expandable intramedullary humeral nail (Dics Orthopaedic Technologies Inc, New Jersey) and post operatively full weight bearing with physiotherapy assistance. The surgical technique of insertion of the nail was clearly and reproducibly documented and standardised across the series. It was not reported who performed the operation, thus raising concerns about the generalisability of the technique to a standard population. All patients were mobilised fully weight bearing on day 1 post op. However, 4 patients were mobilised in a cast boot for 6 weeks and 8 only in wool and crepe - this being reportedly down to patient preference but being a source of performance bias. The study protocol was to remove the nail once the fracture had united, however 6 patients (50%) refused and 1 patient passed away prior to removal.

The results are reported as intention-to-treat at set time points (pre-operatively, then post-operatively at 2 and 6 weeks, 3, 6 and 12 months and then yearly). It is not clear when the outcome data was collected. The Olerud and Molander Score (OMS) [18] has been reported for the day of admission and at a mean of 67 weeks. Given the fact that the study does not clearly state if it is prospective or retrospective, it is unclear whether the day of admission score was collected retrospectively and could represent a source of recall bias. It is also not stated how or who administered these assessments, which could be a source of detection bias. Of the 12 patients included in the study, one died from a myocardial infarction 24 days post operatively. The remaining 11 patients were followed up for a minimum 36 weeks (mean 67). It is reported that all the fractures had united, but not stated who, how or when this assessment was made.

The outcome on which the authors place most emphasis in the results section is the Olerud and Molander Score [18]. The score is a patient assessment tool for symptoms following ankle fracture and comprises elements including; pain, stiffness, swelling, stair-climbing, running, jumping, squatting, use of supports and activities of daily living, and provides a score from 0 to 100 (100 being excellent). It is a validated score but may not be ideally suited to a more elderly population.

The mean pre-injury score was 69.6 and the mean postoperative score 61.4 at a mean of 67 weeks. No statistical analysis has been performed, raising questions as to the relevance of these figures. The 3 patients who died during follow up have final outcome OMS. This raises the question as to if the OMS was completed by all patients at all time points or calculated from clinical review. The high follow up rate does add confidence in the study’s validity. The authors report that all patients were satisfied with their outcome, however no scoring system has been used to assess patient satisfaction. They also report no radiological evidence of degenerative joint disease relating to nail insertion, but do not report when this assessment was made, or how degenerative disease classified. In the discussion the authors advocate the expandable nail’s use for patients with impaired mobility and cite the fact that all their patients had impaired mobility before their injury as evidence, however this is a fallacy of correlation and causation and this conclusion cannot be drawn from their data.

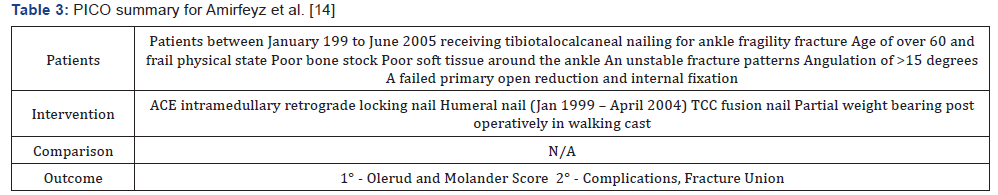

Amirfeyz et al. [13]

This study is a retrospective case review reporting a single hospitals experience on the use of a locked intramedullary hind foot nail for stabilisation of fragility ankle fractures. No study aim is stated, but they use the Olerud and Molander Scale as the primary outcome measure (Table 3). The study protocol was devised retrospectively but included patients within a defined date range treated with tibiotalocalcaneal nailing for ankle fragility fracture. Inclusion criteria were clearly stated and defined where required. Patients not meeting the above were excluded. The inclusion and exclusion criteria were incompletely applied with only 1 of the 13 patients receiving the intervention after a failed primary open reduction and internal fixation, a point which the authors fail to explain. This raises questions of the studies reliability and does little to reduce the risk of selection inherently present in this study design

The intervention and surgical technique were well described, reproducible and the same for all patients. The operations were performed by one of 3 consultant foot and ankle surgeons at the hospital, limiting the generalisability of their results. All patients were mobilised partial weight bearing in a walking cast for 6 weeks and followed up at set time intervals (2, 6-8 weeks, 3, 6 and 12 months, then annually). The OMS was used as the primary outcome measure, but also reported were complications and fracture union. All living patients were interviewed retrospectively. It is not reported who conducted the interview but is a possible source of interviewer bias. For deceased patients a mobility and pain assessment were made based on the last outpatient assessment, inpatient record or physiotherapy notes. This attempted to reduce survivorship bias but created a source of reporting and attrition bias.

The study results report a final outcome score for 7 of the 13 patients with a mean OMS of 50. As there was no comparison group, the single OMS is of limited use. 6 patients died before final interview – 1 in hospital from pneumonia and 5 subsequently from causes unrelated to their surgery. The authors acknowledge the low survivorship of this patient population in the discussion. There was 1 case of superficial wound infection, 1 case of malalignment requiring revision surgery and 1 case of delayed union. It is not stated when radiographs were assessed for union or by whom.

The authors compare pre-injury and post-operative mobility and state that all patients returned to their pre-injury level, however their results table shows that two patients required an increase in mobility aids post-operatively. They also state all patients were very satisfied with their treatment but have not used any tool to measure satisfaction. In the discussion the authors also claim that the mean OMS score of 50 was comparable to the patients’ pre-injury level. This however is an assumption, as they did not measure it.

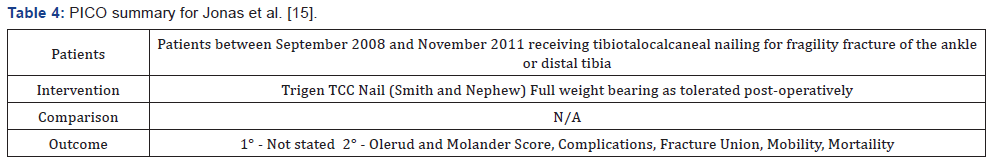

Jonas et al. [14]

This study is a larger retrospective case series aiming to review the functional outcomes of patients with ankle fragility fractures primarily managed using a TCC nail. It was a single hospital study within a well-defined time frame, and collecting a variety of outcome measures including OMS, which was used as their functional outcome (Table 4).

There was no a priori protocol. 31 consecutive patients were identified from the retrospective search. No inclusion or exclusion criteria were stated, although the patient characteristics influencing the decision to treat with a TCC nail were recorded. They included medical co-morbidities, poor soft tissues and inability to comply with a non-weight bearing status. Unstable ankle fractures and 4 distal tibial fractures were included. The inclusion of distal tibial fractures has already been questioned by this review. This study is at a high risk of selection bias. The authors report that all the patients were treated with the same TCC nail, although surgical technique was not described, and it was not clear who performed the operation. Post-operatively all patients were mobilised fully weight bearing as tolerated and followed up at set time points until fracture union. The risk of performance bias is unclear.

The authors clearly describe their complications, which included 3 peri-prosthetic fractures and 2 broken nails. There was a high loss to follow up, both due to death (29%) and also due to infirmity preventing outpatient clinic attendance. This has limited the studies assessment of union, with only 13 patients having radiographic confirmation. The authors have included clinical union (defined as a lack of pain) in their results. If the patient was unable to attend clinic they were contacted by telephone. The authors also report a pre-injury OMS but have not stated if this was collected retrospectively or extrapolated from clinical notes. Overall the outcome reporting is highly susceptible to bias.

The retrospective design and lack of inclusion criteria are acknowledged by the authors as limitations. However, the biggest limitation in this study is the high loss to follow up and the lack of validity caused by handling of these incomplete data sets.

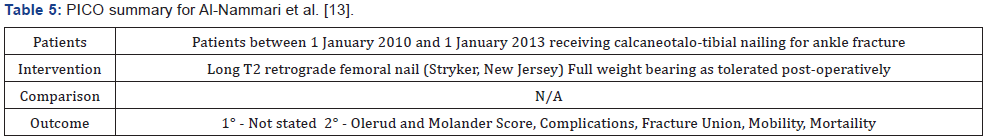

Al-Nammari et al. [12]

This study is a retrospective case review describing a single major trauma centre’s results in treating 48 fragility fractures of the ankle in the frail elderly patient with a long calcaneotalotibial nail. There are no stated outcome measures but the authors report on similar outcomes to the previous 3 studies (Table 5). There is a reasonable sample size, but it includes a slightly different patient demographic with 19/48 (40%) open fractures. Their incidence and inclusion is due to the hospital’s status as a major trauma centre, but is likely to influence the outcomes and raises questions about the validity of the study in standard orthopaedic practice.

There was no a priori protocol and it is unclear if patients were consecutive. There are no inclusion or exclusion criteria and the decision for treatment was at the discretion of the on-call consultant, creating a high risk of selection bias. The intervention was with a long nail passing the isthmus of the tibia (T2 retrograde femoral nail). A long nail was used due to the risk of peri-prosthetic fracture with shorter nail types [14]. The surgical technique is recorded and is reproducible, as were post-operative instructions for full weight bearing and follow up. The procedure was performed by a mix of consultant surgeons and registrars (none experts in foot and ankle surgery) and so is generalisable to the wider orthopaedic community. Follow up was for 6 months. There was no specific outcome data recorded at review and subsequently patients able (alive and with intellectual capacity) to complete a functional assessment were, contacted for OMS. There is no record of if this assessment was conducted by post or over the telephone.

As expected with the inclusion of 19 open fractures, there was a higher complication rate than previous studies. There were 5 incidences of infection, and 3 cases of metalwork complication (all loose or broken distal locking screws). There was also 1 below knee amputation following a failed vascular repair for a Grade IIIc open fracture [19]. There were no cases on non-union or peri-prosthetic fracture. Fracture union was assessed on a combination of clinical and radiological fields, but it is not clear by whom. Mortality at 6 months was 35%, which is reasonable for the population. However, only 14 (29%) of patients were able to complete an OMS questionnaire. There was a high loss to follow up with an inadequate explanation and high risk of attrition bias. The strengths of this paper are the completeness of complication reporting and the larger number of cases. The authors cite the short follow up of 6 months as a limitation, however it is a pragmatic time frame for this patient group and may be long enough to assess the outcomes selected [20].

Discussion

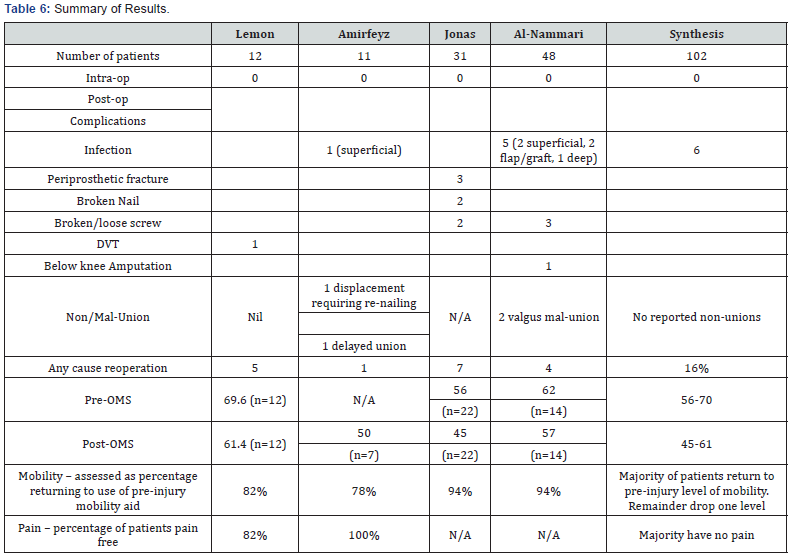

This systematic review has identified 4 studies demonstrating that hindfoot IM nailing for fragility fractures of the ankle can be an effective treatment in an elderly population. However, the intervention is not without risk and this must be balanced against the risks of other treatment modalities by the operating surgeon. There are no comparative studies in the literature to show a benefit of one treatment over another. A summary of the results of the 4 studies is provided in Table 6 and shows that the majority of patients returned to their pre-injury level of mobility and had a ‘fair’ functional outcome assessed by Olerud and Molander Score [18]. There was a total of 6 infections and 17 re-operations for any cause (including 5 elective nail removals in Lemon et al. [15] series).

Across the studies there was a risk of selection and reporting bias, and assessment of the methodology showed significant weaknesses across all the retrospective case reviews. Certain strategies were employed to attempt to reduce bias, such as set inclusion criteria and consecutive recruitment, but these were often poorly implemented. Amirfeyz et al. [14] recommended a prospective randomised trial (RCT) to compare this intervention to more conventional treatment methods. RCTs can be limited by time, cost and external validity, however their methodology does reduce selection bias and account for confounding variables and is best for assessing if a cause and effect relationship does exist.

This systematic review aimed to identify the evidence for hindfoot IM nailing of fragility fractures of the ankle in elderly patients and has done so – showing that there is only a limited amount of level IV evidence currently in the literature which establishes the technique as one that can be employed in this patient population. Further research, ideally a randomised control trial, would be required to show any benefit over current standard treatments. This systematic review has relevance for the wider orthopaedic community as it consolidates current evidence and shows that IM nailing for fragility ankle fractures can facilitate early weight bearing with a comparable complication rate to standard treatment, a fair functional outcome and a high level of preserved mobility.

References

- Court-Brown CM, Caesar B (2006) Epidemiology of adult fractures: A review Injury 37(8): 691-697.

- Court-Brown CM, McBirnie J, Wilson G (1998) Adult ankle fractures-- an increasing problem? Acta Orthop Scand 69(1): 43-47.

- Kanis JA, Oden A, Johnell O, Jonsson B, de Laet C, et al. (2001) The burden of osteoporotic fractures: a method for setting intervention thresholds. Osteoporos Int 12(5): 417-427.

- Beauchamp CG, Clay NR, Thexton PW (1983) Displaced ankle fractures in patients over 50 years of age. J Bone Joint Surg Br 65(3): 329-332.

- Vasarhelyi A, Baumert T, Fritsch C, Hopfenmüller W, Gradl G, et al. (2006) Partial weight bearing after surgery for fractures of the lower extremity--is it achievable? Gait Posture 23(1): 99-105.

- Kamel HK, Iqbal MA, Mogallapu R, Maas D, Hoffmann RG (2003) Time to ambulation after hip fracture surgery: relation to hospitalization outcomes. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 58(11): 1042-1045

- National Clinical Guideline C. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence: Guidance. The Management of Hip Fracture in Adults. Royal College of Physicians, London, UK.

- National Clinical Guideline Centre (2011).

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 339: b2535.

- The Oxford 2011 Levels of Evidence Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine.

- Slim K, Nini E, Forestier D, Kwiatkowski F, Panis Y, et al. (2003) Methodological index for non-randomized studies (minors): development and validation of a new instrument. ANZ J Surg 73(9): 712-716.

- Kim SY, Park JE, Lee YJ, Seo HJ, Sheen SS, et al. (2013) Testing a tool for assessing the risk of bias for nonrandomized studies showed moderate reliability and promising validity. J Clin Epidemiol 66(4): 408-414.

- Al-Nammari SS, Dawson-Bowling S, Amin A, Nielsen D (2014) Fragility fractures of the ankle in the frail elderly patient: treatment with a long calcaneotalotibial nail. Bone Joint J 96-b(6): 817-822.

- Amirfeyz R, Bacon A, Ling J, Blom A, Hepple S, et al. (2008) Fixation of ankle fragility fractures by tibiotalocalcaneal nail. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 128(4): 423-428.

- Jonas SC, Young AF, Curwen CH, McCann PA (2013) Functional outcome following tibio-talar-calcaneal nailing for unstable osteoporotic ankle fractures. Injury 44(7): 994-997.

- Lemon M, Somayaji HS, Khaleel A, Elliott DS (2005) Fragility fractures of the ankle: stabilisation with an expandable calcaneotalotibial nail. J Bone Joint Surg Br 87(6): 809-813.

- Lauge-hansen N (1950) Fractures of the ankle. II. Combined experimental-surgical and experimental-roentgenologic investigations. Arch Surg 60(5): 957-985.

- Marsh JL, Slongo TF, Agel J, Broderick JS, Creevey W, et al. (2007) Fracture and dislocation classification compendium - 2007: Orthopaedic Trauma Association classification, database and outcomes committee. J Orthop Trauma 21(10 Suppl): S1-133.

- Olerud C, Molander H (1984) A scoring scale for symptom evaluation after ankle fracture. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 103(3): 190-194.

- Gustilo RB, Anderson JT (1976) Prevention of infection in the treatment of one thousand and twenty-five open fractures of long bones: retrospective and prospective analyses. J Bone Joint Surg Am 58(4): 453-458.