Peripheral Nerve Block: Does it Affect Pain Perception in Acute Compartment Syndrome? A Systematic Review

Ashraf Elazab1,3*, Ahmed Abd-Elgawad2 and Mohamed Attia2

1Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Dammam Medical Complex, Dammam, Saudi Arabia

2 Department of Anesthesia, Dammam Medical Complex, Dammam, Saudi Arabia

3Department of Orthopedic Surgery, ELsenbellaween, and Mansoura international hospital, Egypt

Submission: June 23, 2018; Published: August 24, 2018

*Corresponding author:Ashraf Elazab, Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Elsenbellaween and Mansoura international hospital, Egypt

Ahmed Abd-Elgawad, Department of Anesthesia, Dammam Medical Complex, Dammam, KSA

How to cite this article:Ashraf E, Ahmed A E, Mohamed A. Peripheral Nerve Block: Does it Affect Pain Perception in Acute Compartment Syndrome? A Systematic Review. Ortho & Rheum Open Access J 2018; 12(4): 555844. DOI: 10.19080/OROAJ.2018.12.555844.

Abstract

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the effect of peripheral nerve block (PNB) on perception of pain induced by compartment syndrome (CS) in orthopedic surgery. Studies emphasized or discussed the relation between PNB and CS until March 2017 were identified in databases. Nine studies were eligible according to our selection criteria. All were case reports. Outcome including pain perception, duration to decompression and tissue necrosis were extracted from selected studies and analyzed. Pain perceived in seven out of nine cases. Decompression time range from 0 to 4 hours from pain perception and 140 min to 48 hours from operation time. Tissue necrosis was observed in three out of nine cases. In conclusion there is no evidence in the literatures supporting the assumption that PNB prevent the perception of CS pain. Accordingly, it could be considered safe for postoperative pain control in orthopedic surgery with special precautions in high-risk patients.

Keywords: Peripheral nerve block; Compartment syndrome; Delayed diagnosis; Orthopedic surgery

Abbrevations: PNB: Peripheral nerve block; CS: Compartment syndrome

Introduction

In modern anesthesia practice the treatment of postoperative pain is a basic human right and an essential part of perioperative care [1]. Regional analgesic techniques were introduced aiming to minimize systemic narcotic usage which could reduce the incidence of known adverse effects including tiredness, nausea, respiratory depression, decreased intestinal motility and urinary retention [2]. Moreover, it correlates with improved patient satisfaction, better short-term outcomes and decreased length of hospital stay [3-6]. Peripheral nerve block (PNB) as a regional analgesic technique widely used for postoperative control in orthopedic surgery. However, its efficacy for postoperative pain control raised concerns for the possible masking of the ischemic pain which is the cardinal diagnostic symptom of the compartment syndrome (CS). That may lead to delay in diagnosis with its catastrophic consequences. CS is an orthopedic emergency, which occurs when perfusion pressure of fascial compartment falls below the tissue pressure with resultant ischemia of muscles and nerves of the compartment [7]. Irreversible tissue damage can occur within 4-6 hours after the onset of symptoms; however, nerves are already severely damaged after 2 hours of increased compartment pressure [8,9].

Diagnosis of CS is mainly clinical. Signs and symptoms include: pain out of proportion to the injury and exacerbating by passive stretching of the involved muscles, swelling and coldness. Late signs of paraesthesia, pulslessness and paralysis follow [10]. Pulslessness may not occur and diagnosis is assisted by invasive measuring of intra compartmental pressure. Urgent faciotomy is the definitive treatment. In the literature, some authors blamed PNB in delaying the diagnosis of CS while others defended. Our purpose was to evaluate the effect of PNB on perception of pain induced by CS in orthopedic surgery

Materials and Methods

Search methods

We searched the databases including PubMed, Cochrane library, Web of Science, Embase, and reference lists of included studies using the following terms: (peripheral nerve block, regional anesthesia, CS, limb ischemia, and ischemic limb pain). Articles discussing the effect of PNB on CS pain perception were identified until the date of last research on 30 April 2017.

Selection Criteria

The inclusion criteria were studies which reported the effect of PNB on compartmental syndrome pain perception in the extremities whether it mask this pain, delay its perception or had no effect. Outcome including pain perception, duration to decompression and tissue necrosis. The pre-specified criteria were used to select the eligible studies by two reviewers (Elazab. A, Abd-Elgawad. A). Any disagreement between the two reviewers about the selected studies was resolved by consulting a third reviewer (Attia .M).

Data extraction

Data regarding the publishing date, patient characteristics, intervention, outcomes including presence of pain, duration to intervention, and tissue necrosis were extracted from the selected studies.

Results

Search results and Description of Studies

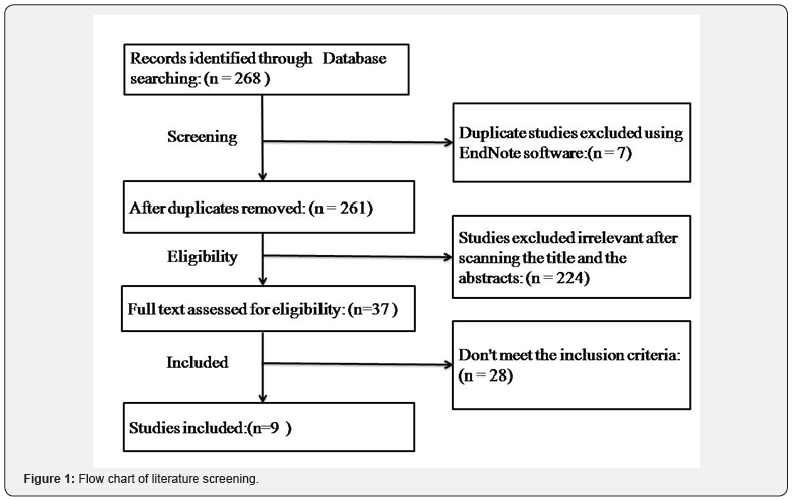

Among initially identified 268 articles that were searched in the databases, 7 duplicates were excluded by using endnote program and 224 citations were excluded after screening the titles and abstracts. After reading full texts, 27 citations, which did not fulfill inclusion criteria, were excluded (Table 1). Ten studies with 10 patients fulfilled the inclusion criteria [1,11-19]. One of them [16] was excluded because the CS occurred outside the blocked area. Lastly 9 cases were included in the analysis all of them were case reports (Figure 1).

These 9 cases were published between 1997 and 2015 and contain 6 males and 3 females with their age ranging from 4 to 75 years. Four of them were in the upper extremities and 5 were in lower extremities.

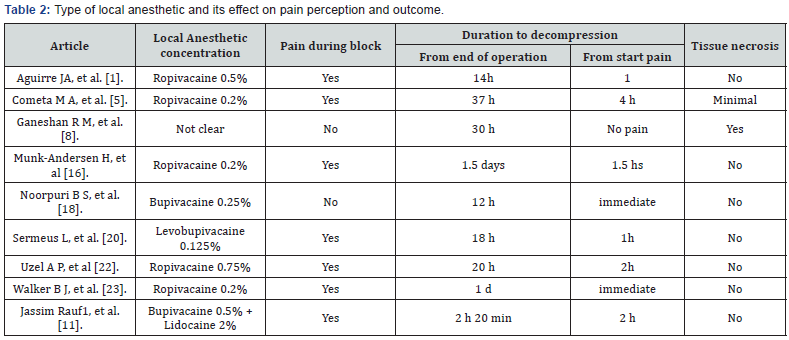

The type of the injected local anesthetic material varied. It was ropivacaine 7.5 % in one study, ropivacaine 0.5 % in one study, ropivacaine 0.2 % in three studies, 0.25% bupivacaine in one study, 0.125% levobupivacaine in one study, one study used a combination of bupivacaine 0.5 % plus lidocaine 2%, and in one study the type of local anesthetic was not clear (Table 2). The nerve block procedure was done preoperatively in six cases, and immediately postoperatively in three cases. General anesthesia was used in eight trials; however, PNB was used as a sole anesthetic only in one trial. The types of intervention were fasciotomy ± debridement and release of external pressure in all cases. Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the included studies. Pain perceived in seven out of nine cases. Decompression time ranged from 0 to 4 hours from pain perception and 140 min to 48 hours from operation time. Tissue necrosis was observed in three out of nine cases.

M; Male, F; Female, BMI: Body Mass Index, DM; Diabetes Mellitus, Dis: Disease, PCRA; Patient Controlled Regional Analgesia.

Discussion

As pain is the cardinal and first alarming symptom of the CS we searched for the perception of pain under a well-functioning nerve block. The main findings in this study were that pain was perceived in 7 [1,11,12, 14,15,18,19] of the 9 cases with wellfunctioning nerve block and in 3 of them [11,14,18] ischemic pain could be perceived under dense sensory and motor block Table 2. In 6 of these 7 cases where pain could be perceived, there was no any muscle necrosis or long-term neural deficit. While in one case [12] some anterior and lateral musculature of the leg was found to be non-viable and removed but without neurological deficit. In this case fasciotomy was done 4 hours after the patient had reported severe pain and his pain cannot be controlled by extra dose of local anesthetic. During this period intra compartmental pressure was measured twice (2 hrs and 3 hrs after pain) and it was high in both readings (more than 30 mm Hg) and lastly fasciotomy done after 4 hours of pain. Of course, we cannot know exactly when the CS started but if we assume that it was started with the first complain of pain, it is possible to get muscle necrosis after 4 hours [9]. So, in this case we can consider as a case of delay in intervention rather than a delay in diagnosis and PNB cannot be blamed in masking the pain as it was clear that the pt can perceive pain under the functioning block.

H = hour, min = minute.

In the remaining two cases [6,13,] the patients did not complain of severe pain during the effect of nerve block. In the first one of them [17] the patient was given ankle block for foot surgery and she was pain free for about 12 hours then complained of severe pain which was not relieved by oral analgesics and CS was diagnosed on clinical basis and immediate fasciotomy done. All muscles were found to be completely viable and there was no any sequel. Because we cannot know when the CS started, there are two possible scenarios. First, we can assume that CS started less than 4 hours from onset of pain but pain was not perceived until the block torn off after 12 hours (which is uncommon for ankle block with bupivacaine 0.25% to stay for 12 hrs). The other possible scenario assumes that the CS did not occur until 12 hours and pain perceived normally at the onset. So, in this case we cannot conclude neither the patient can perceive pain under nerve block nor cannot.

In the last case [13] the patient was a 72 years old male with multiple co morbidities who was operated for redo open reduction internal fixation of his left radius under axillary brachial plexus block and presented after 24 hours from operation with multiple swellings over the forearm and hand with loss of sensation of his fingers. Examination revealed edema of the forearm with multiple hemorrhagic blisters, painful passive movement of the fingers, reduced capillary refilling and reduced sensation over the median nerve distribution. Diagnosis of acute CS was confirmed with intra compartmental pressure measuring which revealed high pressure of 50 mm Hg in the anterior compartment. In this case the patient did not complain of pain, and pain was not the presenting complaint 24 hours after the operation. So, we can explain missing of pain in this case by one of three scenarios.

First assumes that the action of nerve block was prolonged for 24 hours (which is very uncommon) and masked the perception of pain during this period. In second scenario we will assume that pain of CS was masked by the nerve block and the reduced perfusion caused nerve damage that prevented perception of pain after the block had worn off. These two scenarios are refused because the anterior compartment muscles are supplied by both median and ulnar nerves and at presentation the median nerve only was affected while the ulnar was well functioning that means that it was neither blocked nor damaged and it was supposed to carry pain sensation to be perceived. The last possible scenario for explanation is that it was a silent CS rather than an occult one as it is possible for a CS to occur without intractable or even significant pain even in a fully alert patient with sensate limb [20,21].

The mechanism by which ischemic pain is transmitted via blocked nerve is poorly understood. It could have a different pathway from that of surgical pain. Munk et al. [15] showed that surgical pain is primarily mediated through the thin unmyelinated C-fibers and myelinated Aδ- fibers whereas ischemic pain primarily mediates through the thicker A-β fibers. Thus, by using local anesthetics in dilute concentrations, it is possible to obtain sufficient post-operative pain relief without excluding the possibility of ischemic pain being felt by the patient. This explanation is logic but still alone does not explain the cases where ischemic pain was felt with the use of concentrated local anesthetics and dense motor block which means that A alpha fibers (thicker and more resistant to block than A beta fibers) are blocked.

Another explanation is that ischemic pain has a different mechanism which is more intense and sustained than surgical pain. Cometa et al. [12] showed that in ischemic tissue it is postulated that bradykinin, serotonin, acetylcholine, adenosine, potassium ions, and hydrogen ions are some of the substances responsible for ischemic pain [15,22]. Tissue acidosis evidently initiates the pain pathway as increasing levels of hydrogen ion concentration may act on skeletal muscle nociceptors resulting in pain impulse transmission [17]. The hormonal markers of inflammation and injury are thought to undergo tachyphylaxis after nociceptor activation [23]; however, hydrogen ion excitation, in particular, produces non-adapting activation of nociceptors [23,24]. These two explanation theories of different pathway and different mechanism can together give explanation for transmission of pain via a blocked nerve although still not definite; and more experimental work is needed.

Conclusion

There is no evidence in the literatures supporting the assumption that PNB prevent the perception of CS pain. Accordingly, it could be considered safe for postoperative pain control in orthopedic surgery with special precautions in highrisk patients.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

References

- Sermeus L, Boeckx S, Camerlynck H, Somville J, Vercauteren M, et al. (2015) Postsurgical compartment syndrome of the forearm diagnosed in a child receiving a continuous infra-clavicular peripheral nerve block. Acta Anaesth Belg 66(1): 29-32.

- Widmer B, Lustig S, Scholes CJ, Molloy A, Leo SP, et al. (2013) Incidence and severity of complications due to femoral nerve blocks performed for knee surgery. The Knee 20(3): 181-185.

- Akkaya T, Ersan O, Ozkan D, Sahiner Y, Akin M, et al. (2008) Saphenous nerve block is an effective regional technique for post-menisectomy pain. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc16(9): 855-858.

- Hanson NA, Derby RE, Auyong DB, Salinas FV, Delucca C, et al. (2013) Ultrasound-guided adductor canal block for arthroscopic medial meniscectomy: a randomized, double-blind trial. Can J Anaesth 60(9): 874-880.

- Hsu LP, Oh S, Nuber GW, Doty R Jr, Kendall MC, et al. (2013) Nerve block of the infrapatellar branch of the saphenous nerve in knee arthroscopy: a prospective, double-blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume 95(16): 1465- 1472.

- Lundblad M, Forssblad M, Eksborg S, Lonnqvist PA (2011) Ultrasoundguided infrapatellar nerve block for anterior cruciate ligament repair: a prospective, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Eur J Anaesthesiol 28(7): 511-518.

- Wiemann JM, Ueno T, Leek BT, Yost WT, Schwartz AK, et al. (2006) Noninvasive measurements of intramuscular pressure using pulsed phase-locked loop ultrasound for detecting compartment syndromes: a preliminary report. J Orthop Trauma 20(4): 58-63.

- Davis ET, Harris A, Keene D, Porter K, Manji M (2006) The use of regional anaesthesia in patients at risk of acute compartment syndrome. Injury 37(2): 128-133.

- Tiwari A, Haq AI, Myint F, Hamilton G (2002) Acute compartment syndromes. The British journal of surgery 89(4): 397-412.

- Dunwoody J, Reichert, CC, Brown, KL (1997) Compartment syndrome associated with bupivacaine and fentanyl epidural analgesia in pediatric orthopaedics. J Pediatr Orthop 17(3): 285-293.

- Aguirre JA, Gresch D, Popovici A, Bernhard J, Borgeat A (2013) Case scenario: compartment syndrome of the forearm in patient with an infraclavicular catheter: breakthrough pain as indicator. Anesthesiology 118(5): 1198-1205.

- Cometa MA, Esch AT, Boezaart AP (2011) Did continuous femoral and sciatic nerve block obscure the diagnosis or delay the treatment of acute lower leg compartment syndrome? A case report. Pain medicine 12(5): 823-828.

- Ganeshan RM, Mamoowala N, Ward M, Sochart D (2015) Acute compartment syndrome risk in fracture fixation with regional blocks. BMJ Case Rep pii: bcr2015210499.

- Jassim R GI, and Brian O (2012) Acute compartment syndrome and regional anaesthesia – a case report. Rom J Anaesth Intensive Care 22(1): 51-54.

- Munk H AaLT (2013) Compartment syndrome diagnosed in due time by breakthrough pain despite continuous peripheral nerve block. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 57(10): 1328-1330.

- Hyder N, Kessler S, Jennings AG, De Boer PG (1996) Compartment syndrome in tibial shaft fracture missed because of a local nerve block. J Bone Joint Surg Br 78(3): 499-500.

- Noorpuri BS, Shahane SA, Getty CJ (2000) Acute compartment syndrome following revisional arthroplasty of the forefoot: the dangers of ankle-block. Foot & ankle international 21(8): 680-682.

- Uzel AP, Steinmann G (2009) Thigh compartment syndrome after intramedullary femoral nailing: possible femoral nerve block influence on diagnosis timing. Orthopaedics & traumatology, surgery & research OTSR95(4): 309-313.

- Walker BJ, Noonan KJ, Bosenberg AT (2012) Evolving Compartment Syndrome Not Masked by a Continuous Peripheral Nerve Block Evidence-Based Case Management. Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine 37(4): 393-397.

- Badhe S, Baiju D, Elliot R, Rowles J, Calthorpe D (2009) The ‘silent’ compartment syndrome. Injury 40(2): 220-222.

- Bae DS, Kadiyala RK, Waters PM (2001) Acute compartment syndrome in children: contemporary diagnosis, treatment, and outcome. J Pediatr Orthop 21(5): 680-688.

- Mubarak SJ, Wilton NC (1997) Compartment syndromes and epidural analgesia. J Pediatr Orthop, 17(3): 282-284.

- Mar GJ, Barrington MJ, McGuirk BR (2009) Acute compartment syndrome of the lower limb and the effect of postoperative analgesia on diagnosis. Br J Anaesth 102(1): 3-11.

- Price C, Ribeiro J, Kinnebrew T (1996) Compartment syndromes associated with postoperative epidural analgesia. A case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am 78(4): 597-599.