Postsplenectomy Thrombocytosis and Managements

Pata Ramalimgam1*, Kartheek Ganapathri2, Jawahar B3 and Sneha3

1Professor, Department of General surgery, Kamineni Institute of Medical Sciences, India

2Associate Professor, Department of General surgery, Kamineni Institute of Medical Sciences, India

3Post Graduate, Department of General surgery, Kamineni Institute of Medical Sciences, India

Submission: January 11, 2018; Published: February 12, 2018

*Corresponding author: Pata Ramalimgam, Professor, Department of General surgery, Kamineni Institute of Medical Sciences, India, Email: drram.pata@gmail.com

How to cite this article: Pata Ramalimgam, Kartheek Ganapathri, Jawahar B, Postsplenectomy Thrombocytosis and Managements. Open Access J Surg. 2018; 8(1): 555728. DOI: 10.19080/OAJS.2018.08.555728

Introduction

Thrombocytosis is frequently encountered as an incidental laboratory finding [1]. The common etiologies of reactive thrombocytosis are infection, trauma, surgery, and occult malignancy. Splenectomy was found to be one of the main causes of thrombocytosis. The probability of thrombocytosis in patients who have had splenectomy is about 75—82% and about 9% of all reactive thrombocytosis occurrences are caused by this procedure. The platelet count in reactive thrombocytosis is expected to normalize after their solution of the underlying condition [2]. We experienced a patient of extreme thrombocytosis after splenectomy without any complications such as bleeding or thrombosis.

Case Report

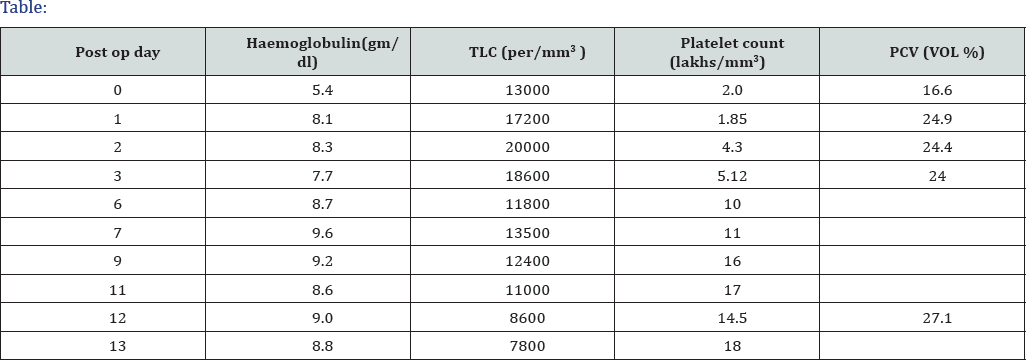

In March 2017, a 36-year-old female patient presented with blunt injury to the abdomen she diagnosed as grade IV splenic laceration. She had no significant past medical or surgical history and denied any medications. Her family history was unremarkable. Physical examination showed tenderness and rebound tenderness in the palpation on left upper quadrant with distension of abdomen. She underwent emergency laparotomy and splenectomy intra and immediate post op period uneventful (Table 1).

She was asymptomatic started on anti platelets to prevent thrombotic events. She underwent CT to rule out any other causes of secondary thrombocytosis such as acute or chronic inflammatory conditions including post operative inflammatory lesions, infectious focuses, or occult malignant lesions. But the test results did not show any other specific abnormal findings. Therefore, we performed bone marrow aspiration and biopsy to rule out myeloproliferative disorders. However, variable cellularity for her age as 20—50% (overall 30%), with normal mega karyocyticcount and morphology was revealed. Also, the erythroid and granulocytic elements were normal in proportion and maturation. It revealed adequate storage of iron without any pathologic ringed side roblasts. But now, with only the help of the antiplatelet agent, she has been asymptomatic and working full-time with no complications, despite her peripheral blood platelet count being over 1,000x 109/L for more than 12 months.

Discussion

The definition of thrombocytosis varies among authors but is most commonly defined as a platelet count >500x109/ L2 and extreme thrombocytosis defined as platelet counts >1,00 0x109/ L3. Thrombocytosis generally either is a reactive process (secondary thrombocytosis) or is caused by a clonal bone marrow (myeloproliferative) disorder; the latter category includes essential thrombocythemia. Reactive thrombocytosis is a common cause of thrombocytosis; the response to infection, trauma, or surgery [3]. In one study of patients with thrombocytosis, reactive thrombocytosis was diagnosed in 70% and primary thrombocytosis in only 22% [4]. Similarly, in patients with extreme thrombocytosis, reactive thrombocytosis is a more common cause of thrombocytosis than primary or essential thrombocytosis. In another study of 280 patients with a platelet count >1,000x109/L, reactive thrombocytosis was the cause in more than 80% and myeloproliferative disorder in only 14% [5].

In that study the etiologies of extreme reactive hrombocytosis are infection (31%), postsplenectomy or hyposplenism (19%), malignancy (14%), trauma (14%), non infectious inflammation (9%), blood loss (6%). Therefore, splenectomy was found to be one of the main causes of extreme reactive thrombocytosis. Another study Yae Min Park et al. [6] Prolonged Extreme Thrombocytosis in a Postsplectomy Pt 301 shows 75% of individuals without myeloproliferative disorders developed thrombocytosis after splenectomy. The spleen plays a major role in platelet regulation, as it is the primary site of destruction of platelets, which is why thrombocytosis is seen with hyposplenism [7,8].

Reactive thrombocytosis is a predictable finding after splenectomy, with the platelet count peaking at 1 to 3 weeks and returning to normal levels in weeks, months, and rarely, years [2]. Regardless of cause, a high platelet count has the potential to be associated with vasomotor (headache, visual symptoms, lightheadedness, atypical chest pain, acral dysesthesia, erythromelalgia), thrombotic, or bleeding complication^ The associations of thrombocytosis with thrombosis and hemorrhage appear to be related to qualitative rather than quantitative platelet abnormalities [9].

Clonal involvement of megakaryocytopoiesis is regarded as the main origin of Thromboembolism in myeloproliferative (MPD) disorder and results in abnormal platelet production. These platelets show increased size heterogeneity and ultra structural abnormalities, and their function in vitro is in many ways impaired with a high degree of individual variability. Elevated levels of platelet-specific proteins, increased thromboxane generation, and expression of activation dependent epitopes on the platelet surface are common on chronic MPD, and may reflect an inappropriate state of platelet activation. Although a variety of platelet receptor deficiencies and some defects of intracellular signaling pathways have been identified, the different platelet defects in MPD could not be traced back to an underlying general pathogenetic mechanism.

On progression of chronic MPD to more advance stages of the disease, the number of platelet abnormalities tend to increase [10]. Postsplenectomy venous thrombosis is usually associated with platelet counts >600x109/L to >80 0x109/L, [6] and occurs in approximately 5% of patients [11]. Less commonly, post splenecto mythrombocytosis results in arterial thrombosis that leads to stroke or myocardial infarction [9]. But these hemostatic events infrequently occur in patients with reactive thrombocytosis [5,12]. This is presumably due to the fact that the interaction of platelets with the vessel wall remains qualitatively normal in secondary thrombocytosis [1]. Neurologic complications including chronic headache or dizziness, or focal neurologic sign occur in about 25 percent of patients with essential thrombocythemia, and may be manifested as nonspecific symptoms [13]. Neurologic complications are presumably caused by platelet-mediated cerebrovascular ischemia [1]. The first step in managing a patient who presents with elevated platelet count is to determine if the etiology is a primary process or a reactive response, because the platelet count in reactive thrombocytosis is expected to normalize after resolution of the underlying condition.

Furthermore because their abnormal platelet count itself does not place them at risk for hemostatic or vascular events, patients with reactive thrombocytosis generally do not require platelet-lowering or antiplatelet treatment. If it is a primary process including essential thrombosis, the immediate risk to the patient from the increased platelet count and additional risk factors for thrombotic complications include advanced age, a history of thrombosis, hypercholesterolemia and cigarette smoking should be assessed. Thereafter, management of the thrombocytosis and prevention of complications should be initiated. Some pharmacologic agents used for this purpose are acetyl salicylic acid, ticlopidine, enoxaparin, hydroxyurea, anagrelide, interferon alpha along with associated adverse effects such as hemorrhage, myelofibrosis, and leukemic transformation [7].

Anagrelide is a newer platelet-lowering agent, an orally administered quinazoline derivative that (Inhibits megakaryocytic proliferation and differentiation) Anagrelide is non leukemogenic and is therefore a particularly reasonable initial option in young patients who require long term platelet count control. Harrison and colleagues compared hydroxyurea plus aspirin with anagrelide plus aspirin as initial therapy for essential thrombocytosis [14]. Common side effects include fluid retention, palpitations, and arrhythmias, heart failure, headaches, and anemia [15]. Long-term data on the side effects and complications of anagrelide are lacking, however, preliminary data suggest it is well tolerated, with mild to moderate anemia as a frequent side effect.

So after weighing the benefits versus the risks of various treatment plans, determine whether reduction of platelet numbers or simple observation is indicated. Although the degree of elevation in the platelet count does not correlate with the risk of thrombosis, control of the platelet count by cytoreduction does reduce the frequency of thrombosis in some patients. Our patient showed extreme thrombocytosis after the splenectomy and the first period of postsplenectomy thrombocytosis, she doesn't complained of headaches, dizziness and a digital tingling sensation, and prophylactically. She received cytoreductive therapy and antiplatelet therapy.

But 2 months after cytoreductive therapy, it was discontinued because the symptoms were resolved. Now it is 19 months after the splenectomy, and she has been asymptomatic and working full-time without any complications, despite her peripheral blood platelet count being over 1,000x109/L for a long duration. In another study where reduction of platelet counts was achieved rapidly, abnormal platelet aggregation testing was present before pheresis, but improved immediately after pheresis. Platelet-sizing data obtained in one case suggested that during the pheresis procedure, a population of larger volume platelets was selectively removed. The efficacy of platelet pheresis in these clinical situations may be related to the selective removal of a large abnormal platelet population [16]. Two or more procedures-either on consecutive or on alternate days-are usually required to achieve adequate reduction in the platelet count. Asymptomatic thrombocytosis does not require removal of platelets unless the patient has a prolonged bleeding time and is about to undergo an operation. Long-term thrombocytapheresis in chronic diseases is not effective [17-19]. These patients who are symptomatic due to extreme thrombocytosis fall under the Category II indication for therapeutic apheresis according to the American Society for Apheresis guidelines [20].

References

- Schafer AI (2004) Thrombocytosis. N Engl J Med 350: 1211-1219.

- Greer JP, Foerster J, Rodgers GM (2008) Wintrobe's Clinical Hematology, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, USA, pp. 1128-1134.

- Santhosh Kumar CR, Yohannan MD, Higgy KE, al-Mashhadani SA (1991) Thrombocytosis in adults: analysis of 777 patients. J Intern Med 229(6): 493-495.

- Tefferi A, Ho TC, Ahmann GJ, Katzmann JA, Greipp PR (1994) Plasma interleukin-6 and C-reactive protein levels in reactive versus clonal thrombocytosis. Am J Med 97(4): 374-378.

- Buss DH, Cashell AW, O'Connor ML, Richards F, Case LD (1994) Occurrence, etiology, and clinical significance of extreme thrombocytosis: a study of 280 cases. Am J Med 96(3): 247-253.

- Hayes DM, Spurr CL, Hutaff LW, Sheets JA (1963) Post-splenectomy thrombocytosis. Ann Intern Med, Yae Min Park, Prolonged Extreme Thrombocytosis in a Postsplectomy Pt 58: 259-267.

- Khan PN, Nair RJ, Olivares J, Tingle LE, Li Z (2009) Post splenectomy reactive thrombocytosis. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent) 22(1): 9-12.

- Bullen AW, Losowsky MS (1979) Consequences of impaired splenic function. Clin Sci (Lond) 57(2): 129-137.

- Daya SK, Gowda RM, Landis WA, Khan IA (2004) Essential thrombocythemia-related acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. A case report and literature review. Angiology 55(3): 319323.

- Wehmeier A, Sudhoff T, Meierkord F (1997) Relation of platelet abnormalities to thrombosis and hemorrhage in chronic myeloproliferative disorders. Semin Thromb Hemost 23(4): 391-402.

- Stamou KM, Toutouzas KG, Kekis PB, Nakos S, Gafou A, et al. (2006) Prospective study of the incidence and risk factors of post splenectomy thrombosis of the portal, mesenteric, and splenic veins. Arch Surg 141(7): 663-669.

- Buss DH, Stuart JJ, Lipscomb GE (1985) The incidence of thrombotic and hemorrhagic disorders in association with extreme thrombocytosis: an analysis of 129 cases. Am J Hematol 20: 365-372.

- Kesler A, Ellis MH, Manor Y, Gadoth N, Lishner M (2000) Neurological complications of essential thrombocytosis (ET). Acta Neurol Scand 102: 299-302.

- Harrison CN, Campbell PJ, Buck G, Wheatley K, East CL (2005) Hydroxyurea compared with anagrelide in high-risk essential thrombocythemia. N Engl J Med 353(1): 33-45.

- Storen EC, Tefferi A (2001) Long-term use of anagrelide in young patients with essential thrombocythemia. Blood 97(4): 863-866.

- Orlin JB, Berkman EM (1980) Improvements of platelet function following plateletpheresis in patients with myeloproliferative diseases. Transfusion 20: 540-545.

- Urbaniak SJ, Robinson EA (1990) ABC of transfusion. Therapeutic apheresis. BMJ 300: 662-665.

- Boxer MA, Braun J, Ellman L (1978) Thromboembolic risk of postsplenectomy thrombocytosis. Arch Surg 113: 808-809.

- Johnson M, Gernsheimer T, Johansen K (1995) Essential thrombocytosis: underemphasized cause of large-vessel thrombosis. J Vasc Surg 22: 443-447.

- Szczepiorkowski ZM, Winters JL, Bandarenko N, Kim HC, Linenberger ML, et al. (2010) Guidelines on the use of therapeutic apheresis in clinical practice-evidence-based approach from the Apheresis Applications Committee of the American Society for Apheresis. J Clin Apher 25(3): 83-177.