Abstract

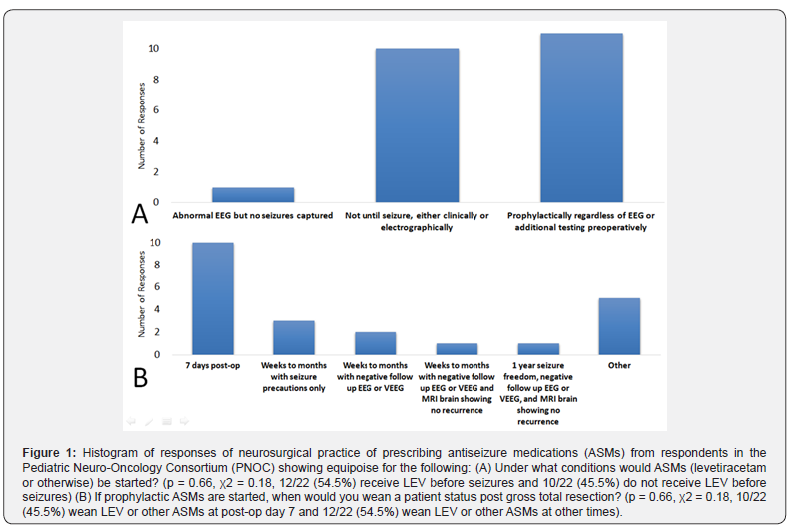

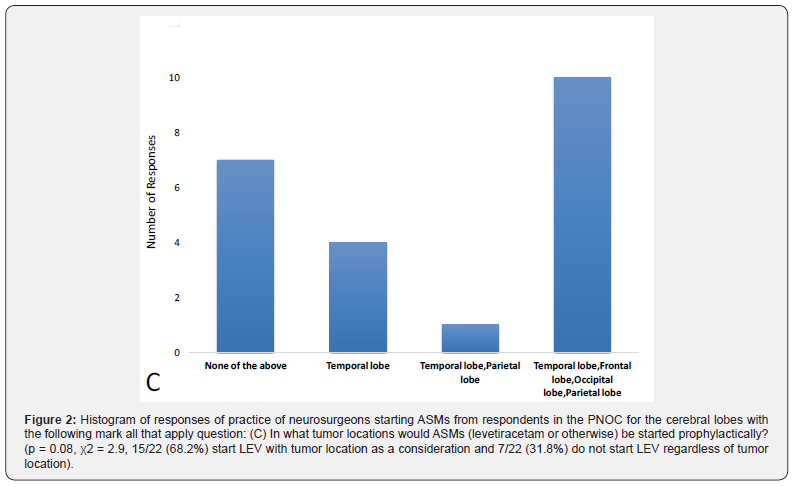

Primary central nervous system tumors occur in children presenting with complaints such as headache, ataxia, weakness, and numbness. Patients with supratentorial tumors often have comorbid seizures at presentation, but a minority do not. For patients presenting with supratentorial tumors without seizures, the practice of initiating and stopping seizure medications is nonstandard. We wrote a survey which was administered to neurosurgeons in the Pediatric Neuro-Oncology Consortium (PNOC) which demonstrated nonstandard initiation of antiseizure medications such as levetiracetam in this population with variable criteria for initiation including prophylactically regardless of patient history (11/22,50%), with an abnormal electroencephalography (EEG) regardless of history (1/22,4.5%), and following seizure regardless of other features (10/22,45.5%) which is not statistically significant (p = 0.66, χ2 = 0.18). The location of the tumor also appears to have some impact on the prescription of antiseizure medications as there was a trend for significance for tumors located in specific lobes (15/22,68.2%) while a minority of providers would not prescribe antiseizure medication (7/22,31.8%) regardless of tumor lobe location (p = 0.08, χ2 = 2.9). We also found nonstandard weaning practice from providers with responses being 7 days post-op (10/22,45.5%), weeks to months with seizure precautions only (3/22,13.6%), weeks to months with negative follow up EEG (2/22,9.1%), weeks to months with negative follow up EEG and Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) of the brain showing no recurrence of disease (1/22,4.5%), 1 year seizure freedom with negative follow up EEG and MRI of the brain showing no recurrence of disease (1/22,4.5%), and other (5/22,22.8%). Even with the most common weaning practice which is weaning at post-op day 7 (10/22,45.5%) versus all other weaning practices (12/22,54.5%), we again demonstrate equipoise as this difference is not statistically significant (p = 0.66, χ2 = 0.18). We demonstrate a nonstandard medical practice due to heightened but uncertain risk of occurrence of seizures in children who have supratentorial tumors but who have never had seizures previously. These results implicate the need for prospective registries or clinical trials to demonstrate clinical effectiveness of antiseizure medications in this tumor subpopulation..

Keywords: Seizures; Epilepsy; Antiseizure medications; Levetiracetam; Supratentorial tumor; Craniotomy; Resection; Quality of life; Electroencephalogram; Magnetic resonance imaging

Abbreviations: ASMs: Antiseizure Medications; EEG: Electroencephalogram; IRB: Internal Review Board; LEV: Levetiracetam; MRI: Magnetic Resonance Imaging; PNOC: Pediatric Neuro-Oncology Consortium; QoL: Quality of Life; SUDEP: Sudden Unexplained Death in Epilepsy

Introduction

In the United States, about 5000 children and adolescents are diagnosed with primary brain tumors each year, with 40% being supratentorial [1,2]. Children with supratentorial tumors present for a variety of complaints including seizures, headaches, ataxia, weakness, numbness, and other focal neurologic deficits [3]. Of the minority of children who present with supratentorial tumors without seizures, who are at a heightened but uncertain risk of occurrence of seizures, levetiracetam (LEV) is often utilized to prevent seizures due to few interactions with chemotherapy [4-7]. Unfortunately, LEV also causes neuropsychiatric side effects, such as depression, anxiety, and psychosis, which are already highly prevalent in patients with supratentorial tumors [7-10]. Side effects of LEV can lower quality of life (QoL) in pediatric patients who already suffer reduced life expectancy with high morbidity and mortality due to their cancer [11-13].

Current treatment strategies of supratentorial tumors in patients without history of seizures include craniotomy with resection, chemotherapy, and radiation, while treatment of seizures remains limited and nonstandard due to uncertain estimation of risk of seizures, resulting in prescription of antiseizure medications (ASMs) without clear benefit [4,5]. There is a critical need to identify and develop novel treatment protocols to standardize care for these patients and reduce postoperative seizures for high-risk patients and side effect burden of antiseizure medications in low-risk cases.

Due to our observation of nonstandard care of prescribing and weaning ASMs for these patients at our center, our hypothesis was that children with heightened but unclear risk of recurrence of seizures such as children with supratentorial tumors without history of seizures receive nonstandard care. We sought to understand the degree of equipoise and variability of care nationally for children with supratentorial tumors without history of seizures. The long-term goal of this study is to promote research to improve the standardization of care for these pediatric patients and a better understanding of the risk factors promoting epileptogenesis in children with supratentorial tumors presenting without seizures to appropriately tailor prescription and weaning of ASMs [14,15].

Materials and Methods

Internal Review Board (IRB) approval for protocol #16111 for analysis of perioperative prescribing habits of providers who care for patients with supratentorial tumors was obtained prior to this study. A brief survey was designed by the authors and administered to neurosurgeons who are members of the Pediatric Neuro- Oncology Consortium (PNOC) with n=22 participants responding. Board certified neurosurgeons were selected for this survey as they were most likely to care for patients with supratentorial tumors without history of seizures at admission and initiate ASMs before, during, or after surgery. Data was collected on the practices of these providers with the major outcomes being the practice of initiating ASMs in children with supratentorial tumors who have not yet seized as well as timing and workup prior to stopping ASMs in children with supratentorial tumors who have not yet seized. As a secondary measure, we acquired responses from these providers about characteristics of the tumor locations which would prompt the initiation of ASMs as a mark all that apply response on the survey. All data collected for this study were categorical and were analyzed with chi-squared statistics (χ2).

Results

We found equipoise of practice with initiation of ASMs by neurosurgeons in PNOC with 11/22 (50%) providers starting prophylactic ASMs in all cases regardless of history, 10/22 (45.5%) providers starting ASMs only after seizures, and 1/22 (4.5%) providers starting ASMs with an abnormal EEG (Figure 1, p = 0.66, χ2 = 0.18, 12/22 (54.5%) receive LEV or other ASMs before seizures and 10/22 (45.5%) do not receive LEV or other ASMs before seizures).

There was also variability in the practices of weaning ASMs once ASMs are initiated even status post gross total resection of the tumor with 10/22 (45.5%) providers weaning at post-op day 7, 3/22 (13.6%) providers weaning weeks to months with seizure precautions and no additional testing, 2/22 (9.1%) providers weaning weeks to months with negative follow up EEG, 1/22 (4.5%) providers weaning weeks to months with negative follow up EEG and MRI of the brain showing no recurrence, 1/22 (4.5%) providers weaning with 1 year seizure freedom with negative follow up EEG and MRI of the brain showing no recurrence, and 5/22 (22.8%) providers weaning with “other” criteria which were not one of our responses to the survey (Figure 1, (p = 0.66, χ2 = 0.18, 10/22 (45.5%) wean LEV or other ASMs at post-op day 7 and 12/22 (54.5%) wean LEV or other ASMs at other times).

Location of tumor also likely impacts the decision to start ASMs when respondents were given a mark all that apply question asking what tumor locations would prompt the initiation of ASMs with statistical analysis approaching significance. Most respondents answered that lobe location would impact initiation of ASMs, while a minority would not start ASMs regardless of tumor location (Figure 2, p = 0.08, χ2 = 2.9, 15/22 (68.2%) start LEV with tumor location as a consideration and 7/22 (31.8%) do not start LEV regardless of tumor location).

Discussion

The initiation and weaning of ASMs for children with supratentorial tumors without history of seizures and likely other groups of patients with heightened but unclear risk of seizures is nonstandard. For those patients who clearly have a 60% or greater risk of occurrence of seizures, a practical diagnosis of epilepsy is made and seizure medications should be prescribed [5]. Reduction of seizures with medication, dietary, and surgical management is important to prevent injuries from seizures and the risk of occurrence of sudden unexplained death in epilepsy (SUDEP) [14,16,17]. For those with medically intractable epilepsy defined as failure of two antiseizure medications at high dose independent of a surgical lesion, presurgical workups should also be performed as surgical management has higher efficacy for these patients than medical management alone [14,18,19].

On the other hand, there are many groups of patients who are at heightened but unclear risk of occurrence of seizures as they may have risk greater than the general population which is 1% but less than that of the definition of epilepsy which is > 60% [5,20]. Examples of these patients with heightened but unclear risk of recurrence of seizures include those with lesions of grey matter but no history of seizures, patients with a single seizure but normal EEG and MRI of the brain, patients with variants of unknown significance in genes causing epilepsy without history of seizures, and patients with provoked seizures [4,14,21-24].

Provoked seizures from reversible causes include metabolic derangement, hypoxia, intoxication/withdrawal, trauma with intracranial hemorrhage, and supratentorial tumors [4,14,21- 24]. Our study demonstrates a gap in knowledge which results in nonstandard practice of prescribing ASMs in children with supratentorial tumors without history of seizures. Study of these children longitudinally following gold standard treatment of their tumors with resection, chemotherapy, and radiation as appropriate will be required to identify high and low risk children who may benefit from ASMs or possibly experience harm from side effects to their QoL with low benefit owing to their low risk of seizures. Prospective study of children with supratentorial tumors without history of seizures will clarify the risk of post operative seizures and standardize the prescribing of ASMs. Standardization of ASMs is aimed to reduce post operative seizures in appropriate high-risk cases while also reducing unnecessary prescriptions in those who are low risk and thus likely to experience side effects without significant benefit.

This study is limited by its analysis of retrospective practice of providers with a single survey which may be susceptible to recall bias. Future directions include additional prospective study of physician practice of initiating and weaning ASMs in patients with supratentorial tumors without seizures to mitigate recall bias.

Conclusion

The prescription of ASMs and the weaning of ASMs for children presenting with supratentorial tumors without history of seizures is currently nonstandard. There is equipoise of management among board certified neurosurgeons nationally based on responses to our survey. Our data suggests that study of patients with supratentorial tumors without seizures should be performed to identify high risk and low risk factors which predict likely early and late post operative seizures as well as those who can be managed without ASMs. The goal of this research is to prevent post operative seizures while also not diminishing QoL of patients with already severe disability, morbidity, and mortality due to their tumor with additional side effects of unnecessary ASMs.

Data Availability Statement

The survey and data supporting this manuscript are available and can be obtained by contacting the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Pediatric Neuro-Oncology Consortium (PNOC) participants who provided the data for this project [25].

References

- Price M, Ballard C, Benedetti J, Neff C, Cioffi G, et al. (2024) CBTRUS Statistical Report: Primary Brain and Other Central Nervous System Tumors Diagnosed in the United States in 2017-2021. Neuro Oncol 26(Supplement_6): vi1-vi85.

- Walker D, Hamilton W, Walter FM, Watts C (2013) Strategies to accelerate diagnosis of primary brain tumors at the primary-secondary care interface in children and adults. CNS Oncol 2(5): 447-462.

- Boldrey E, Naffziger HC, Arnstein LH (1950) Signs and symptoms of supratentorial brain tumors in childhood. J Pediatr 37(4): 463-468.

- Saadeh FS, Melamed EF, Rea ND, Krieger MD (2018) Seizure outcomes of supratentorial brain tumor resection in pediatric patients. Neuro Oncol 20(9): 1272-1281.

- Fisher RS, Acevedo C, Arzimanoglou A, Bogacz A, Cross JH (2014) ILAE official report: a practical clinical definition of epilepsy. Epilepsia 55(4): 475-482.

- Wright C, Downing J, Mungall D, Khan O, Williams A, et al. (2013) Clinical pharmacology and pharmacokinetics of levetiracetam. Front Neurol 4: 192.

- Patsalos PN (2004) Clinical pharmacokinetics of levetiracetam. Clin Pharmacokinet 43(11): 707-724.

- Halma E, de Louw AJ, Klinkenberg S, Aldenkamp AP, IJff DM, et al. (2014) Behavioral side-effects of levetiracetam in children with epilepsy: A systematic review. Seizure 23(9): 685-691.

- Benson J, Sarangi A (2022) Psychiatric Considerations in Pediatric Patients with Brain Tumors. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 24(6): 21r03228.

- Sharma A, Das AK, Jain A, Purohit DK, Solanki RK, et al. (2022) Study of Association of Various Psychiatric Disorders in Brain Tumors. Asian J Neurosurg 17(4): 621-630.

- Szabados M, Kolumbán E, Agócs G, Kiss-Dala S, Engh MA, et al. (2024) Association of tumor location with anxiety and depression in childhood brain cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 17(1): 124.

- Benson J, Sarangi A (2022) Psychiatric Considerations in Pediatric Patients With Brain Tumors. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 24(6): 21r03228.

- Subramanian S, Ahmad T (2024) Childhood Brain Tumors. [Updated 2023 Aug 8]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls.

- Miller D (2024) Childhood Epilepsies and When to Refer for Epilepsy Surgery Evaluation. IntechOpen.

- Rakhade SN, Jensen FE (2009) Epileptogenesis in the immature brain: emerging mechanisms. Nat Rev Neurol 5(7): 380-391.

- Dlouhy BJ, Gehlbach BK, Richerson GB (2016) Sudden unexpected death in epilepsy: basic mechanisms and clinical implications for prevention. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 87(4):402-413.

- Maguire M, Jackson C, Marson A, Nevitt S (2020) Treatments to prevent sudden unexplained death in epilepsy (SUDEP). The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 4: CD011792.

- Baumgartner C, Koren JP, Britto-Arias M, Zoche L, Pirker S (2019) Presurgical epilepsy evaluation and epilepsy surgery F1000Res 8: F1000 Faculty Rev-1818.

- Kwan P, Arzimanoglou A, Berg AT, Brodie MJ, Hauser WA, et al. (2010) Definition of drug-resistant epilepsy: Consensus proposal by the ad hoc task force of the ILAE commission on therapeutic strategies. Epilepsia 51(6): 1069-1077.

- Russ SA, Larson K, Halfon N (2012) A national profile of childhood epilepsy and seizure disorder. Pediatrics 129(2): 256-64.

- Lauren M Maynard, James L Leach, Paul S Horn, Christine G Spaeth, Francesco T Mangano, et al. (2017) Greiner, Epilepsy prevalence and severity predictors in MRI-identified focal cortical dysplasia. Epilepsy Research 132: 41-49.

- Temkin NR, Dikmen SS, Wilensky AJ, Keihm J, Chabal S, et al. (1990) A randomized, double-blind study of phenytoin for the prevention of post-traumatic seizures. N Engl J Med 323(8): 497-502.

- Hillbom M, Pieninkeroinen I, Leone M (2003) Seizures in alcohol-dependent patients: epidemiology, pathophysiology and management. CNS Drugs 17(14): 1013-1030.

- Moosa ANV (2019) Antiepileptic Drug Treatment of Epilepsy in Children. Continuum (Minneap Minn) 25(2): 381-407.

- Pediatric Neuro-Oncology Consortium. Advancements Through Collaboration. Updated: 2025.