Complications of Acute Sinusitis: A Review and Case Series

Aiwain Yong1, Anas Gomati2, Kenneth Khor3, May KheiHu3 and Avinash Kumar Kanodia4*

1Department of Radiology, Aberdeen Royal Infirmary, UK

2Department of ENT, Aberdeen Royal Infirmary, UK

3Department of Paediatrics, Aberdeen Royal Infirmary, UK

4Department of Radiology, Ninewells Hospital, UK

Submission: October 05, 2020; Published: October 20, 2020

*Corresponding author: AK Kanodia, Department of Radiology,Ninewells Hospital, Dundee, UK

How to cite this article: Yong A, Gomati A, Khor K, KheiHu M, Kanodia AK. Complications of Acute Sinusitis: A Review and Case Series. Open Access J Neurol Neurosurg 2020; 14(3): 555888. DOI: 10.19080/OAJNN.2020.14.555888.

Abstract

Acute rhinosinusitis is a common infection, however a small proportion of cases can progress to serious complications with significant morbidity and mortality. Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis, subdural empyema, meningitis, cerebral abscess and cerebritis are some of the potential intracranial complications. Orbital complications include peri and orbital cellulitis, the latter requiring treatment with surgical drainage and intravenous antibiotics. We present a review and case series of patients with complications from acute sinusitis, correlate the imaging to their clinical presentations and briefly discuss their clinical management.

Introduction

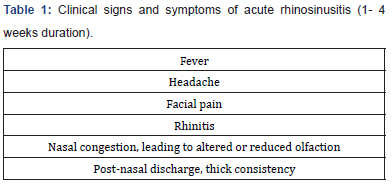

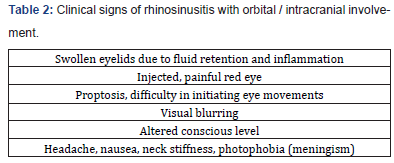

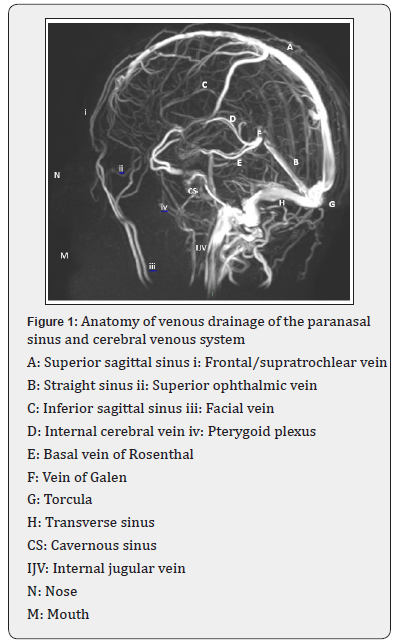

Acute rhinosinusitis (ARS) is an inflammatory process of the nasal mucosa and paranasal sinuses, usually caused by viral infection and is usually self-resolving (Table1). The true incidence of acute virus rhinosinusitis has always been described as high [1], with an estimation that shows adults are likely to suffer two to five episodes of viral ARS per year, in comparison to seven to ten episodes per year in children [2]. Post-viral ARS occurs as a perpetuation of the inflammatory condition, even when the viral agent has been eliminated, with a reported estimate of 3.4 cases per 100/year [3]. It is also estimated that only 0.5–2% would progress to Acute Bacterial Rhinosinusitis (ABRS).The incidence of ABRS complications is approximately 3 per million of the population per year, despite vastly different utilization of antibiotics in various countries. This figure has not reduced significantly despite the advent of widespread antibiotic prescribing [4]. Delays in starting treatment, incomplete antibiotic regiment or immunosuppression are some of the risk factors leading to complications from acute rhinosinusitis [5]. Complications of ABRS include periorbital, intra-cranial and osseous conditions which are potentially life-threatening (Table2), where an early commencement of intravenous antibiotics and /or surgical drainage is carried out. This is imperative to avoid long term sequelae. In all studies, orbital complications are the most frequent while osseous appear to be relatively uncommon, with males significantly more affected than females. Orbital complications appear more common in children while intracranial complications can occur at any age, with a preponderance of young adults [4,5]. Anatomy of paranasal sinus venous drainage and cerebral venous drainage up to 3% of patients with ARS present with orbital inflammation including preseptal cellulitis and orbital cellulitis, orbital abscess and subperiosteal empyema [5,6]. Orbital inflammatory complications are often caused by infection of ethmoid or frontal sinus due to their proximity to the orbits [7]. The ethmoid sinuses are drained by anterior and posterior valveless ethmoidal veins, and in conjunction with delicate lamina papyracea which offer the route of least resistance for infection to travel into the orbit [5]. The valveless ethmoidal veins drain into ophthalmic veins, thus increasing risk of cavernous venous sinus thrombosis from ethmoid sinusitis [5]. Approximately 3% of intracranial complications such as cerebritis, subdural empyema, meningitis, venous sinus thrombosis and cerebral abscess are due to sinusitis [8], commonly arising from frontal sinus, followed by sphenoid, ethmoid and maxillary sinuses.

The abundant emissary valveless venous Behcet’s plexus of the posterior frontal sinus mucosa communicates with diploic veins and dura [5] where infection can spread through intact sinus walls to intracranial dura, meninges and parenchyma. The emissary and diploic veins network from the frontal sinuses which communicate with valveless dural venous system and cavernous sinus allow propagation of infection and septic thrombi, hence cause cerebral venous sinus thrombosis. Anterior to frontal sinus, infection can spread through the bony wall or via diploic venous drainage causing thrombophlebitis with or without frank osteomyelitis to cause a subgaleal abscess, called Pott’s puffy tumor which is rarely seen since the introduction of antibiotics [5,9].The maxillary vein which drains both sphenoid and maxillary sinuses forms a network with pterygoid venous plexus (Figure 1) which communicates with the dural sinuses at the skull base, allowing spread of infection causing meningitis [10].

Surgical management and relevant anatomical landmarks

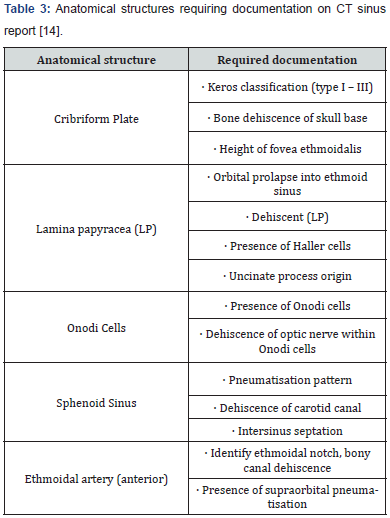

Methods of surgical intervention have evolved in the past two decades, to more minimally invasive functional endoscopic sinus surgeries, that could at times be combined with open approaches. Despite these less invasive approaches and advances in technology, they still carry risks for developing serious life-threatening complications. Surgical intervention is usually reserved for complicated acute rhinosinusitis, which in turn has specific clinical and radiological findings. On initial surgical assessment, careful consideration is taken to highlight, if any symptoms or signs suggesting intra / extra cranial complications including orbital complications, followed by endoscopic examination when tolerated, which usually demonstrates evidence of pus and injected nasal mucosa. Computed Tomography (CT) scan of sinuses aids in confirming the diagnosis, delineates extent of complications, facilitates surgical planning and provides an opportunity to identify anatomical variations that predispose patients to surgical complications. A general principal is that when ARS complications require surgical treatment (e.g. intra-cranial abscess, orbital / subperiosteal abscess, Pott’s puffy tumor), then concomitant surgical drainage of the affected sinuses is usually recommended [11]. The key critical areas the surgeon needs to be aware of on imaging are those that place patients at risk for surgical complications. A mnemonic based approach provides a simplistic means for recalling the critical variants to report and document on the pre-operative scans. The mnemonic ‘CLOSE’ (cribriform plate, lamina papyracea, Onodi cell, sphenoid sinus pneumatisation, and (anterior) ethmoidal artery), has been popular amongst ENT surgeons (Table 3).

Acute sinusitis and imaging

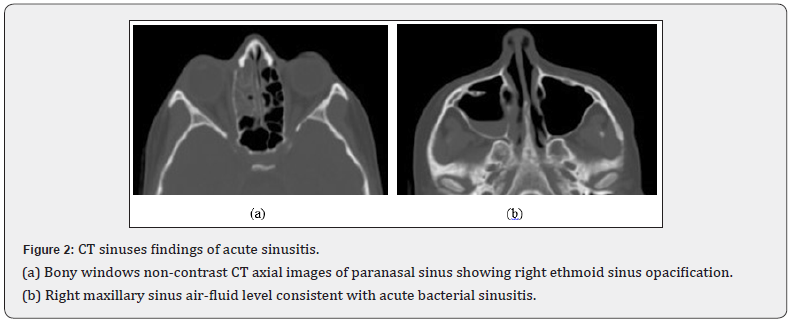

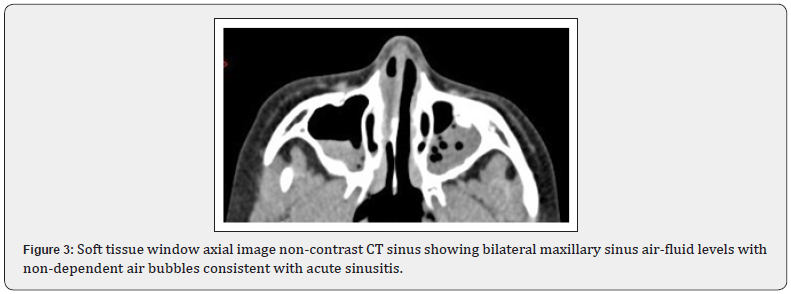

The paranasal sinuses are best evaluated with fine-slice CT reconstructed using high-resolution bony algorithm of 1mm or less. Soft tissue windows should be included to evaluate paranasal sinus opacification, as the different densities demonstrated would give further information about its contents.

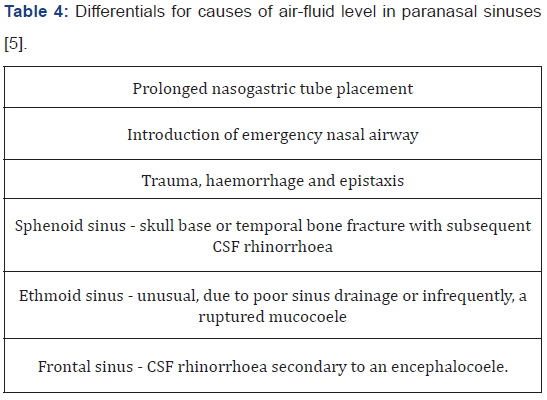

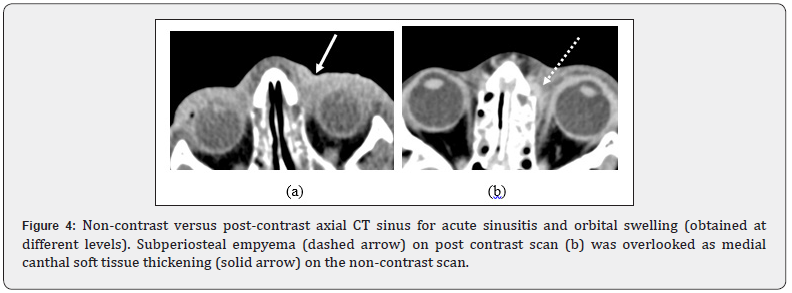

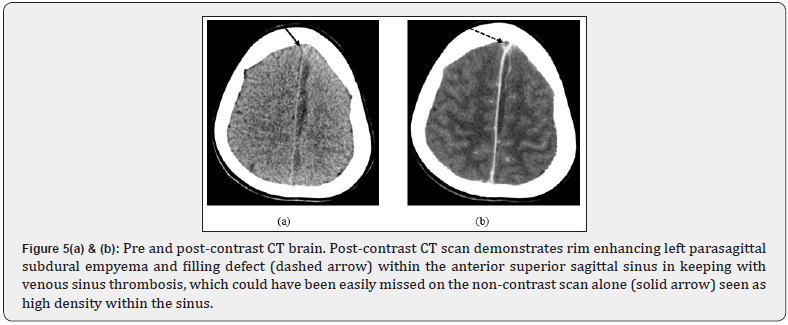

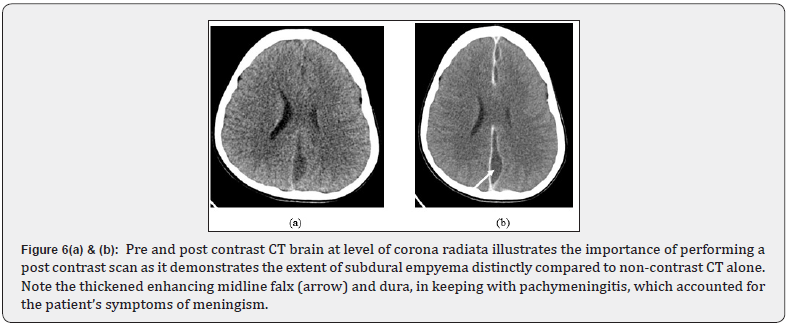

MRI scan of paranasal sinuses should be considered in cases of intracranial complications or when further evaluation is required for possible paranasal soft tissue mass or neoplasm. In acute emergencies where clinically a differential of acute orbital cellulitis or possible intracranial extension of disease secondary to acute sinusitis is raised, the radiologist responsible for overseeing the protocol of the CT examination should always consider performing a contrast-enhanced scan at initial presentation, especially in the paediatric population. Post contrast scans are superior to non-contrast CT in delineating rim-enhancing collections, identifying presence of venous sinus thrombosis and demonstrating the extent of intracranial complications. Moreover, it would save patients from unnecessary radiation exposure from acquiring a repeat CT scan with contrast when performed from the outset. Dental sinusitis remains a common cause for maxillary sinusitis, therefore CT sinuses should always include the upper jaw teeth to allow for complete evaluation [12]. CT sinuses for patients with acute rhinosinusitis typically demonstrates sinus opacity and mucosal thickening (Figures 2, 3&4) [13]. Paranasal sinus air-fluid level is often demonstrated; however should be correlated clinically, as there are several causative differentials, depending on site (Table 4). In the presence of clinical acute rhinosinusitis however, air-fluid level in maxillary or frontal sinus usually indicates acute bacterial rhinosinusitis with obstruction of sinus drainage necessitating urgent surgical management to reduce risk of intracranial or orbital complications (5).

Clinical Examples

Venous sinus thrombosis, pachymeningitis and subdural empyema

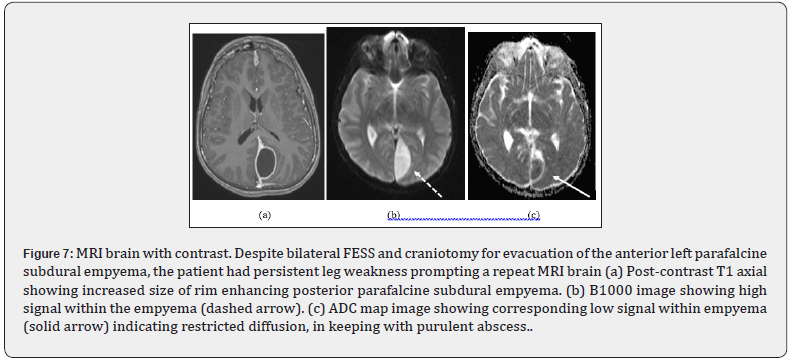

An 11-year-old boy presented with swollen red painless right eye associated with drowsiness, neck stiffness, photophobia and left lower limb weakness. An emergency CT brain showed superior sagittal sinus thrombosis and subdural empyema, (Figure 5) with complete opacification of his left frontal, ethmoid and maxillary sinuses. He underwent bilateral functional endoscopic sinus surgery (FESS) and was treated with intravenous antibiotics and unfractionated heparin. However, the headache persisted with minimal recovery of his left leg weakness. Post contrast CT head performed showed unresolved subdural empyema (Figure 6), which was then evacuated. Despite this, subsequent Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) brain showed further enlargement of posterior parafalcine subdural empyema (Figure 7). This led to 2 STEALTH-guided Burr holes surgeries to drain it with subsequent complete recovery.

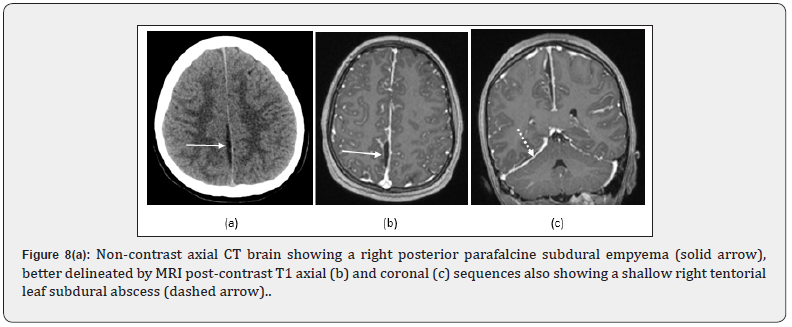

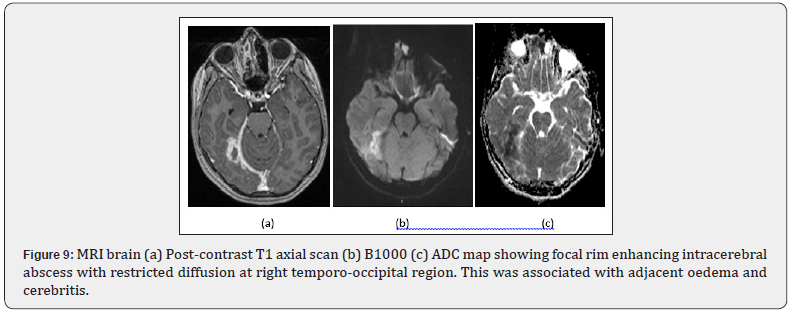

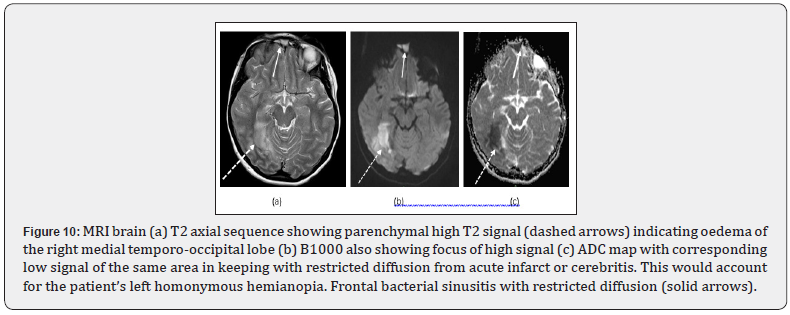

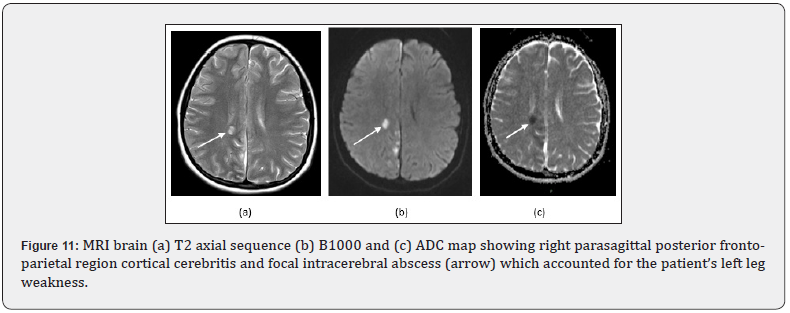

Subdural empyema, cerebritis and cerebral abscess A 15-year-old girl presented with fever, lower limb weakness, a right retro-orbital headache, rhinitis, photophobia and left homonymous hemianopia. A non-contrast CT brain showed opacification of right frontal sinus with bilateral maxillary sinus air-fluid levels and a shallow right parafalcine subdural empyema (Figure 8). An MRI head was also performed (Figures 8, 9, 10) to identify cause of her visual disturbance and limb weakness (Figure 11). She underwent surgical drainage of right frontal sinus. The subdural empyema was managed with intravenous antibiotics [14].

Presumed traumatic subdural haematoma

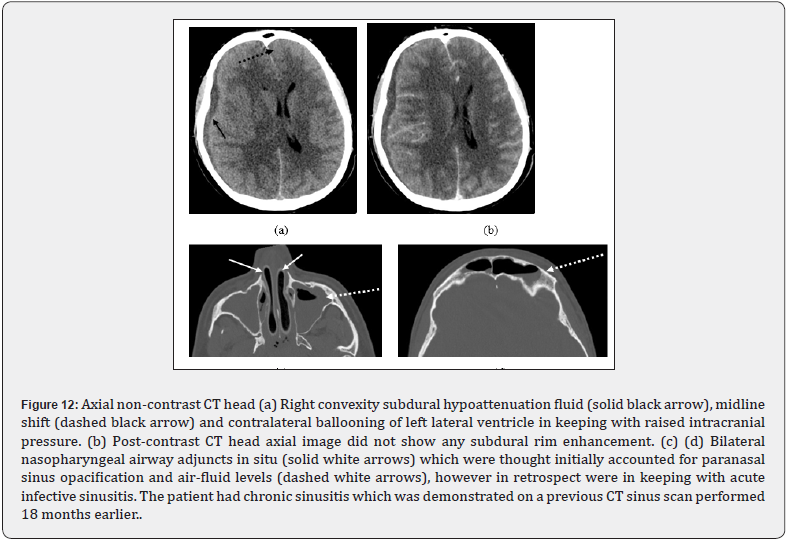

A 20-year-old male presented to Accident and Emergency when found collapsed with a GCS score of 4 and unequal pupil sizes. An urgent CT brain was performed (Figure 12) showed a moderate sized subdural fluid causing significant mass effect. The neurosurgeons performed emergency craniotomy for evacuation, which revealed not a subdural haematoma as thought initially but a large subdural empyema.

On retrospective review, the hypoattenuating subdural fluid on CT brain was initially reported as hyperacute right subdural haematoma secondary to presumed trauma, as there was no rimenhancement on post-contrast CT brain. There were left maxillary and frontal sinuses opacification with air-fluid levels which were overlooked. An endoscopic sinus surgery was carried out to drain the sinuses.

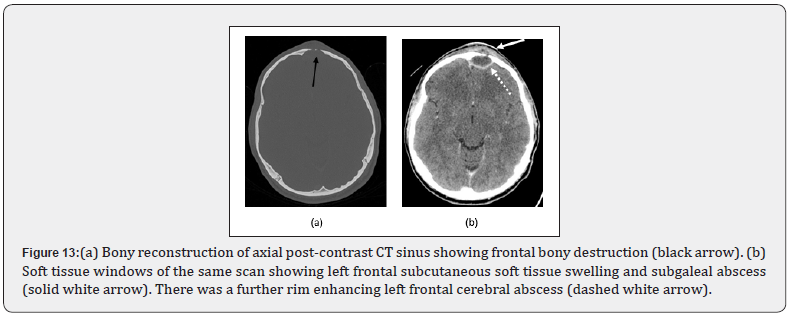

Frontal subcutaneous oedema and abscess - Potts Puffy tumor

A 30-year-old male presented with intermittent vomiting, fever, frontal headache and slowly progressive, tender swelling over the forehead. Post contrast CT brain (Figure 13) was performed showed a frontal extradural/subgaleal abscess associated with left frontal sinusitis and dehiscence of the anterior and posterior frontal sinus walls (Figure14), in keeping with Pott’s puffy tumor. The patient underwent trans-cranial needle aspiration of the extradural abscess, left external frontal trephination via a Lynch Howarth incision and left endoscopic sinus surgery. Intra-operative findings included severely inflamed nasal mucosa with frank pus in the left maxillary, ethmoidal and frontal sinuses which were washed out and a corrugated drain was placed.

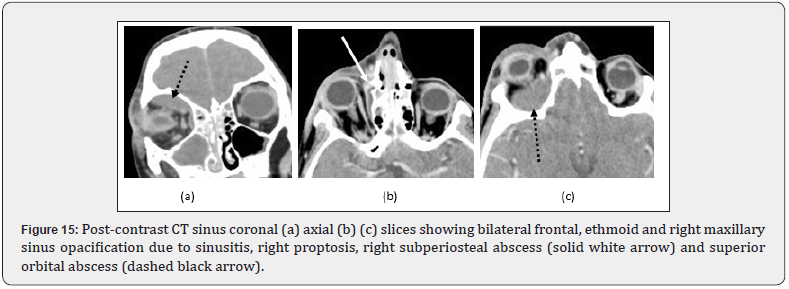

Orbital cellulitis with intra-orbital abscess and subperiosteal empyema

A 10-year-old boy presented with progressive right eye swelling, proptosis, reduced eye movement and difficulty eye opening. CT sinuses performed revealed right-sided orbital cellulitis with intra-orbital abscess (Figure 15), and opacification of the paranasal sinuses. He was commenced on intravenous antibiotics. The paranasal sinuses and orbital abscess were drained with complete recovery.

Conclusion

Most episodes of acute rhinosinusitis run a definite and limited course, usually with complete resolution. However, a small percentage can result in serious orbital or intracranial complications which require urgent surgical management. Post-contrast CT head with fine bony reconstructions should be considered as first-line imaging in these circumstances, as certain crucial findings can be missed on non-contrast scans alone. MRI is usually required for orbital or intracranial complications. Good communication between medical, surgical and radiology teams is essential to pinpoint the correct diagnoses and facilitate timely planning of surgical interventions to achieve the best outcomes.

References

- Fokkens W, Lund V, Bachert C, P Clement, P Helllings, et al. (2005) EAACI position paper on rhinosinusitis and nasal polyps executive summary. Allergy 60(5):583-601.

- Jaume F, Quintó L, Alobid I, Mullol J (2018) Overuse of diagnostic tools and medications in acute rhinosinusitis in Spain: a population-based study (the PROSINUS study). BMJ open 8(1):e018788.

- Oskarsson JP, Halldorsson S (2010) An evaluation of diagnosis and treatment of acute sinusitis at three health care centers. Laeknabladid 96(9):531-535.

- Fokkens WJ, Lund VJ, Hopkins C (2020) European position paper on rhinosinusitis and nasal polyps. Rhinology 58:1-464.

- Som PM, Curtin HD (2011) Head and Neck Imaging E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences 239-241.

- Babar-Craig H, Gupta Y, Lund VJ (2010) British Rhinological Society audit of the role of antibiotics in complications of acute rhinosinusitis: a national prospective audit. Rhinology 48(3): 344-347.

- Guerrant RL, Walker DH, Weller PF (2011) Tropical Infectious Diseases: Principles, Pathogens and Practice E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences1006.

- TK Nicoll, M Oinas, M Niemela (2016) Intracranial Suppurative Complications of Sinusitis. Scandinavian Journal of Surgery Feb 105(4): 254-262.

- Gupta M, El-Hakim H, Burgava R, Mehta V (2004) Pott’s puffy tumour in a pre-adolescent child: the youngest reported in the post-antibiotic era. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology 68(3):373-378.

- Pandolfo I, Gaeta M, Blandino A,Longo M(1987) The radiology of the pterygoid canal: normal and pathologic findings. American journal of neuroradiology 8(3): 479-483.

- Desrosiers M, Evans GA, Keith,Erin D Wright, Alan Kaplan, et al.(2011) Canadian clinical practice guidelines for acute and chronic rhinosinusitis. Allergy, Asthma & Clinical Immunology 7(1): 2.

- Whyte A, Boeddinghaus R(2019) Imaging of odontogenic sinusitis. Clin Radiol74 (7): 503-516.

- Heidi Beate Eggesbø (January 16th 2020). Imaging in Sinonasal Disorders.

- Weitzel EK, Floreani S, Wormald PJ (2008) Otolaryngologic heuristics: a rhinologic perspective. ANZ journal of surgery 78(12):1096-1099.