The SARS-COV2 Global Outbreak: A Neurosurgical Treatment Algorithm Made Possible in a Low-Resource Scenario

Caio Perret1*, Raphael Bertani1, Paulo Santa Maria1, Stefan Koester2 and Ruy Monteiro1

1Department of Neurological Surgery - Miguel Couto Municipal Hospital Laboratory for Neuroprotection and Regenerative Strategies Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ) / Fundação Osvaldo Cruz (FioCruz)Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil

2Department of Basic Sciences, Vanderbilt University, United States

Submission: June 17, 2020; Published: September 02, 2020

*Corresponding author: Caio Perret, Department of Neurological Surgery - Miguel Couto Municipal Hospital, Rua Mário Ribeiro, 117 - Second Floor, Leblon, Rio de Janeiro, RJ - 22.430-160, Brazil

How to cite this article: Caio P, Raphael B, Paulo S M, Stefan K, Ruy M. The SARS-COV2 Global Outbreak: A Neurosurgical Treatment Algorithm Made Possible in a Low-Resource Scenario. Open Access J Neurol Neurosurg 2020; 14(1): 555878.DOI: 10.19080/OAJNN.2020.14.555878.

Abstract

Not until March 11th, the outbreak of the novel coronavirus was declared to be a global pandemic. It is a reasonable consensus to hold the statement that, throughout the world, the vast majority of the healthcare systems were not prepared to manage and constrain disease spreading and treatment. Despite curve flattening strategies, most of the specialty facilities had to withhold, reduce or even cancel their activities to aid the urging need of intensive and non-intensive care unit efforts engaged in SARS-COV2 infection management. Considering the remainder functional neurosurgery facilities in underdeveloped countries, most of the departments are facing the conundrum in considering what is preconized by the society’s recommendations, and what the healthcare professionals are covering in the already overloaded working scenarios. This article intends to report our center’s experience and crisis management organization as one of the functional departments in a low resource scenario considering the current evidence and society’s recommendations, hence aiding the formulation of algorithms and institutional protocols in centers facing the same challenges.

Keywords: COVID-19; SARS-COV2; Neurological surgery algorithm; Low-resource scenario

Abbreviations:CFR: Case Fatality Ratio; CSSE: Center for Systems Science and Engineering; ICU: Intensive Care Unit; JHU: Johns Hopkins University; PCR: Polymerase Chain Reaction; PGY: Post Graduation Year; PPE: Personal Protection Equipment; UCSF: University of California San Francisco

Introduction

Not until March 11th has the outbreak of the novel coronavirus been declared as a global pandemic by the World Health Organization [1]. What was first said to be a local infection in the city of Wuhan[2], coronavirus infection now is present in 185 countries, accumulating over 133.000 deaths and over 2 million cases, according to the COVID-19 Dashboard by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University (JHU) [3]. It is a reasonable consensus to hold the statement that, throughout the world, the vast majority of the healthcare systems were not prepared to manage and constrain disease spreading and treatment. Regarding most of the undeveloped countries and low-income scenarios of clinical practice, the outbreak of SARS-COV2 represented the dawn of what we are experiencing to be one of the most challenging moments in their history [4,5], considering the lack of consensual authorities recommendations, the poor social and economic governmental protective measures, and the severe infrastructural limitations of the public and private healthcare systems (including the most basic operative needs to most of the workers, such as insufficient personal protective equipment and the short availability of tests). In this uncertain context, the fragile curve flattening strategies were jeopardized by an intricate social and political scenario, leading to quick failure of the health system capacity to handle the expansion of the pandemics.

In Brazil, the numbers are known to be hardly a distant representation of the actual landscape of the pandemics [6]. Currently, (and by the time of the former World Health Organization and the Ministry of Health prediction to be the peak of the SARS-COV2 in Brazil), on April 15, 2020, there were 28. 320 confirmed cases and 1736 deaths due to the infection, according to the statistic officially provided by the Brazilian Ministry of Health [5]. Most of these cases concentrated in the southeast region of the country, which is densely populated and accounts for a high urbanization rate. In addition to the inherent clinical burden, the flail of the curve flattening measures and the poor availability of tests, the increasing demand for healthcare attention to other clinical conditions is rampaging, since most of the specialty facilities had to withhold, reduce or even cancel their activities to aid the urging need of intensive and non-intensive care units efforts engaged in COVID-19 infection management, including neurosurgery [1,4,6,7,8]. Considering the remainder functional neurosurgery facilities in underdeveloped countries, most of the departments are facing the conundrum in considering what is preconized by the society’s recommendations, and what is feasible in such a delicate scenario to deal with the urgent surgical support demanded. In consensus with the recently published article by the Department of Neurological Surgery of the University of California San Francisco[9], the pressure in the neurosurgical practice our unit is facing is concealed to 1- the decision to cancel elective cases outpatient clinics, 2-organizing staff (both graduated practitioners and resident physicians) to lessen exposure risk, and 3- handling neurosurgical emergencies in situations of extremely impoverished availability of both intensive and non-intensive care unit beds imposed by the upheaval of COVID-19 suspect cases.

Although the rapidly evolving nature of the pandemic expansion and the rapid response imposed by this scenario should be thoroughly taken in consideration, as well as the local characteristics of the neurosurgical practice facilities, this article intends to comprehensively review the scientific literature and report our center’s experience and crisis management organization as one of the functional departments in a low resource scenario considering the current evidence, the societies recommendations, and ultimately the need of providing urgent and emergent neurosurgical care while reducing viral transmission, allowing centers facing the same challenges to build and adapt the algorithm to their reality.

Objective

To expose our experience as a working neurosurgical facility in a low-income scenario during the global pandemics of SARSCOV2, considering what is feasible among the most recent society’s recommendations and scientific literature evidence, hence aiding the urge for organization among our specialty during the crisis.

Methods

We performed a literature review by searching the terms COVID-19 and SARS-COV2 in PubMed and manually assorting the results for the relevance to neurosurgical practice, as well as surgical case scheduling, low-income scenarios, and residency program schedule. Articles in English and Portuguese were considered for this review. In the light of the revision, we analyzed the recommendations of the Rio de Janeiro Municipal and State Secretary of Health, the Brazilian Ministry of Health, and the World Health Organization, regarding surgical and outpatient clinics scheduling, contingency measures, and academic activities directives to formulate an algorithm to be followed based on the rapidly and unstable progression of the pandemics.

Results

Except for the neurosurgical treatment algorithm provided by the Neurosurgical Surgery Department of the University of California San Francisco (UCSF) [9], no other articles regarding neurosurgical practice and scheduling were published since the beginning of the virus global expansion. Although, several recommendations regarding healthcare facilities organization [8,10] and, in consensus with the Brazilian Neurosurgical Society [7], the Brazilian Ministry of Health [5] and the World Health Organization Strategic Preparing and Response Plan recommendations [4], all the non-urgent/emergent surgical schedule should be postponed during the pandemics. Considering the triage recommendations adopted by the UCSF Neurosurgical Department and the Brazilian Neurosurgical Society, and mostly the endeavor that the Brazilian Healthcare System is facing on providing reliable data on the infection rates of the community, we decided to cancel the non-emergent outpatient clinics as well as to maintain our service closed to transfers of non-emergent cases during the pandemics.

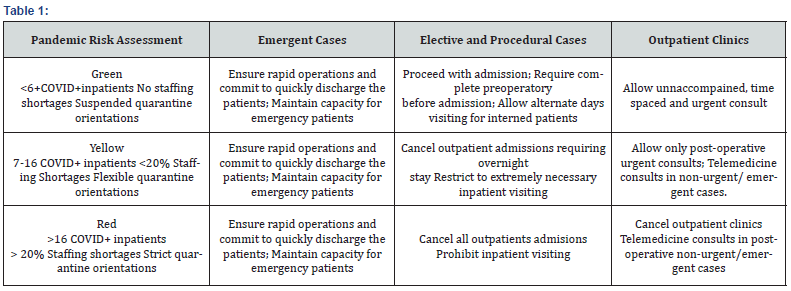

Our orientation is prone to gradually progress, in two steps, from Only Emergent cases to Emergent and Urgent, to Normal outpatient activity, as the infection rates decrease, and the resource demands shift back to normality. The adopted threshold to transition between the steps is based on the Pandemics Risk Assessment, (adapted from the Surge level assessment designed by the Neurosurgical Department of the UCSF), which involves analyzing the staffing shortages, the quarantine orientation of local public administration and the number of COVID+ inpatients (Table 1).

Throughout all the levels of the Risk Assessment proposed during the outbreak, the emergent surgery support is covered by house resident physicians and the house staff, following a paired coverage model, in which each day is to be covered by one resident of each year of the licensed residency program (from PGY1 to PGY5), and one house staff, allowing no overlapping encounters of the remainders to avoid unnecessary exposition. We proposed an online-based shift passage table to ensure continued care and quick discharge for the post-operative cases, minimizing the usual rounding healthcare professionals’ contact. Both the residents and staffs were contacted and instructed to virtually provide patients information to the anesthesia colleagues as well as the other members of the multi-professional healthcare workers during the outbreak, to ensure consonance on the pacing of the approach and to ensure effective communication and time shortening strategy on the patient treatment and discharge. All the inpatients were re-assessed to ensure the extreme need to conclude treatment in the unit, to avoid unnecessary inhospital stay. Long term intravenous antibiotic treatments firstly employed to treat surgical complications were transitioned to oral medication, when considered microbiologically safe, to achieve patient condition for discharge. Unstable patients in the post-operative care of life-threatening conditions admitted to the infirmaries were maintained in the institution with strict visiting restrictions, based on the risk assessment.

If symptomatic, any working professional should suspend in hospital activities and stay in domestic observation during 14 days starting on the onset of the symptoms, according to the Brazilian Ministry of Health recommendation. All of the symptomatic healthcare professionals are specifically instructed to be tested upon symptoms onset and after their resolution, returning to normal activities once the viral load is undetectable and the individual is symptom-free considered non-transmissive of the disease. Regarding teaching academical activities and scientific meetings, all the faculty and professionals were instructed to conduct the meetings through remote virtual strategies. Noncrucial research activities and graduate students were dismissed during the outbreak to minimize hospital circulation and inpatients expositions. We recommended shifting professionals to engage in writing activities while the new patient enrollments were held suspended.

Discussion

As its quick and global rampaging numbers lead to the World Health Organization recognition as a pandemic infection,1 Coronavirus is a respiratory virus and is now known to potentially cause not only respiratory failure and death [11] but also a myriad of other clinical conditions, including neurological imbalances[12]. Even though it is estimated that up to 36% of the hospitalized patients sustaining SARS-COV2 infections develop neurologic related manifestations, and these findings usually are present in more severe cases [13], the neurologic management of coronavirus disease is not currently under the spotlight of the discussion since they often do not require urgent or emergent care. In contrast, the challenging provision of neurologic and neurosurgical care for our field urgent and emergent pathologies during SARS-COV2 pandemics draws the attention of the medical community, taking in consideration the increasing demand Coronavirus is imposing in the healthcare systems throughout the world.

In Italy, considered to be a developed country, counting with almost five times more intensive care beds per 100.000 habitants than what there are available in Brazil, neurosurgical care diminished its workload in almost 70% as the healthcare system collapsed with the surge of the infection [14]. Similar situations are imposing neurosurgical services to quickly react and reorganize to overcome what several are considering to be one of the most challenging times of our specialty. Especially when considering low/middle-income scenarios and underdeveloped countries, the priority levels of medical care provision and constant surge level reassessments are vital for defining the departments’ policies during the crisis [1,4,8,9].

As far as the field is concerned, it is extremely important to our departments to consider the surgical needs of urgent and emergent neurosurgical care of intracranial hypertension, spinal instability, severe traumatic brain injuries and pediatric unstable malformations[7,9] while formulating their policies, once the shortage of ICU capacity and PPE availability will probably affect the deliverance of proper care[15]. Furthermore, the social distancing (i.e. quarantine) public orientations is a recognized curve flattening strategy that should both be considered by medical specialties in returning to host non-urgent outpatient clinics[4,7]. When feasible, telemedicine should be considered to deliver orientations to patients, to minimize staff and hospitalized patients’ exposure. Another important aspect considered in our algorithm is the restriction of visitors and circulating personnel hospital facilities, which might be a huge source of dissemination of SARS-COV2 from reference units to uninfected locations [5].

Mass testing of the population in our public healthcare scenario is still a challenge and, once the only way to assess and plan the next steps in the management of the pandemic is by case confirmation, novel methods of quantification are necessary. A recent study estimated the under notification by comparing the Case-Fatality Ratio (CFR) adapted to the Brazilian population’s age composition to the CFR actually observed up to the moment, indicating the notification of only 8,0% (7,8% - 8,1%) of all COVID-19 cases [16]. Since mass testing of the population is seldomly expected to be achieved in most of the low/middleincome scenarios of neurosurgical practice, our algorithm does not include the number of local cases, as does the UCSF algorithm9, but the number of hospitalized patients with documented SARSCOV2 infection. This could be used as a parameter of the surge level in each institution. The remainder criterion elected to compose our algorithm is the staffing shortage expected to occur during pandemics. As many neurosurgery senior practitioners are above 60 years old, these professionals are considered as a risk group for severe SARS-COV2 infection and should be withheld from service during the pandemics [5,7]. Regarding symptomatic personnel, we are currently recommending domestic observation and realtime PCR testing in day three of symptom development [5], with returning to normal activity once viral loads are undetectable and SARS-COV2 IgG levels are documented. If any professional held close unprotected contact with documented SARS-COV2 patient, even if asymptomatic, we recommend domestic observation for 14 days and testing with real-time PCR [5,17,18].

Since the implementation of the aforementioned measures and until the submission of this paper, there have been five laboratory-confirmed symptomatic COVID-19 cases among the 31 physicians in our neurosurgical department, one resident and four attending-physicians, although we have had no known cases of neurosurgical patients’ contamination (confirmed or suspected). We have also had two senior neurosurgeons, aged over 60, preventively suspended until the scenario allows their return to their duties.

It is of our understanding that neurosurgical practice throughout the globe is developed in varied infrastructural conditions and technical development, challenging the formulation of a consensual algorithm to be imposed in the diverse scenarios. Besides, as previously stated, the comprehensive review yielded very scarce evidence, and even indirect debate, on the field of surgical planning and neurosurgical care during the pandemics, while no reports were found debating specifically neurosurgical care in low-income scenarios during the pandemics. This report of our experience intended to address and aid some of the crucial topics on the orientation of these policies, which ultimately should be carefully tailored to the reality of the social and healthcare landscape where each neurosurgical department takes place.

Conclusion

General healthcare practice orientations during the SARSCOV2 pandemics are showing to be seldomly consensual and hardly universally suitable, considering the vast diversity of healthcare infrastructural and socio-economic conditions. Providing continued neurosurgical care during the SARS-COV2 pandemics is one of the greatest challenges of the history of our specialty and should be attained through organized and dynamic responses to the surges of the infection in the community, especially considering low/moderate income scenarios.

Conflicts of Interest

All the listed authors declare to have no conflicts of interest regarding this publication.

References

- World Health OrganizationWHO director-general opening remarks at the briefing on COVID-19.

- Tong Y,Ren R (2020) Early Transmission Dynamics in Wuhan, China, of Novel Coronavirus-Infected Pneumonia. N Engl J Med382(13):1199-1207.

- Dong E, Du H, Gardner L (2020) COVID-19 in real time. Lancet Infect Dis.3099(20):19-20.

- World Health Organization. 2019 Novel Coronavirus Strategic Preparing and Response Plan.

- (2020) Ministério da Saúde do Brasil. Coronavírus e novo coronavírus: o que é, causas, sintomas, tratamento e prevençã 2020.

- (2020) Fundação Oswaldo Cruz. MonitoraCovid-19 Fiocruz.

- Borba LAB, Pahl FH, Rotta JM, Honda PM, de Oliveira JG (2020) Carta abertaaosneurocirurgiõesbrasileiros - ComunicadoSociedadeBrasileira de Neurocirurgia.

- Chopra V, Toner E, Waldhorn R, Washer L (2020) How Should U.S. Hospitals Prepare for Coronavirus Disease 2019(COVID-19)? Ann Intern Med 172(9): 621-622.

- Burke JF, Chan A, Mummaneni V (2020) The Coronavirus Disease 2019 Global Pandemic: A Neurosurgical Treatment Alrogithm. Neurosurgery1-7.

- Pilar IM Del, Tsin A, Chen C, Ulysses Ribeiro-Júnior, Estevez Diz, et al. (2020) How should health systems prepare for the evolving COVID-19 pandemic? Reflections from the perspec- tive of a Tertiary Cancer Center. Clinics 75: e1864.

- Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, Guohui Fan, Ying Liu, et al. (2020) Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet395(10229): 1054-1062.

- Pleasure SJ, Green AJ, Josephson SA (2020) The Spectrum of Neurologic Disease in the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Pandemic Infection: Neurologists Move to the Frontlines. JAMA Neurol 1065.

- Mao L, Jin H, Wand M, Yu Hu, Shengcai Chen, et al. (2020) Neurologic Manifestations of Hospitalized Patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Neurol 77(6): 1-9.

- Borsa S, Bertani G, Pluderi M, Locatelli M (2020) Our darkest hours (being neurosurgeons during the COVID-19 war). Acta Neurochir (Wien) 162(6): 1227-1228.

- Murthy S, Gomersall CD, Fowler RA (2020) Care for Critically Ill Patients with COVID-19.1-2.

- Prado M, Bastos L, Batista A (2020) Análise de subnotificação do número de casosconfirmados da COVID-19 no Brasil. NúcleoOperações e InteligênciaemSaúde7:1-5.

- Lauer SA, Grantz KH, Bi Q,Forrest K Jones, Qulu Zheng, et al. (2020) The Incubation Period of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) From Publicly Reported Confirmed Cases: Estimation and Application. Ann Intern Med172(9):577-582.

- Ferguson NM, Laydon D, Nedjati-gilani GReport 9: Impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) to reduce COVID-19 mortality and healthcare demand. Imp Coll COVID-19 Response Team.