From Headache to Migraine, Including Episodic and Chronic Migraine

Egilius LH Spierings*

Medical Director, Boston Headache Institute, Boston Pain Care, Waltham, USA

Submission: June 26, 2020; Published: July 20, 2020

*Corresponding author: Egilius LH Spierings, Boston Pain Care, 85 First Avenue Waltham, MA 02451, USA

How to cite this article: Egilius LH Spierings. From Headache to Migraine, Including Episodic and Chronic Migraine. 2020; 14(1): 555876. DOI: 10.19080/OAJNN.2020.14.555876.

Abstract

Headache is a ubiquitous experience, highly non-specific in nature. Tension headache and migraine are its most common presentations, with the difference between them mostly reflected in headache intensity. It is proposed that the high intensity of migraine headache, its essential feature, is caused by a genetically determined and inherited headache amplifier. It is further hypothesized that this headache amplifier resides in the threshold at which the mechanism of neurogenic inflammation is activated. High headache frequency, the characteristic feature of chronic migraine, is postulated to be due to craniocervical hypertonia caused by an associated systemic disorder. It’s scientific truth that we seek. Studies well performed and interpreted help us find it. They themselves are not the truth. Adapted from Philip Delves Broughton. (What they teach you at Harvard Business School. Penguin Books, 2009)

Keywords: Headache; Migraine; Episodic migraine; Chronic migraine; Headache triggers; Tension headache; Migraine aura, Spreading cortical depression; Neurogenic inflammation; CGRP; CGRP antibodies; Botox®

Introduction

Headache is a ubiquitous experience, highly non-specific in nature. Like any kind of pain, it can range in intensity from merely a discomfort, like a pressure in the head, to excruciating head pain that causes people to bang their head against the wall. There is virtually nothing that cannot bring it on, from trivial issues such as fatigue to very significant conditions like brain cancer. Its presentation is almost as non-specific as its etiology, with mode of onset and temporal pattern sometimes providing a clue as to its origin. An example of the former is subarachnoid hemorrhage, with headache of very acute or peracute onset, coming on like a blow to the head. Examples of the latter are the shorter-lasting paroxysmal headache disorders, such as cluster headache, paroxysmal hemicrania, and stabbing headache. Fortunately, the vast majority of headaches do not originate from illness, although that certainly does not diminish the suffering. In fact, the lack of illness often adds to the suffering because of the implied belief that relief can only be obtained with identification and subsequent elimination of the underlying illness. Regardless of etiology, headaches vary in intensity, although intensity, even when high, is not predictive of illness.

In fact, the opposite tends to be true in the sense that the more intense the headache, the less likely the presence of illness. In this regard, mild headaches can be as much a manifestation of illness, even serious illness like brain cancer, as severe headaches. There is no such thing as the worst headache ever and it is a medical myth that it is predictive of subarachnoid hemorrhage or anything else calamitous. Headache intensity is, however, important in the sense that it drives medical consultation. This is because higher intensity level headaches are generally migraine headaches, which are associated with delayed gastric emptying. It is this delayed gastric emptying that makes them not responsive to simple analgesics and not the mere intensity of the headaches. Of course, non-responsiveness is relative to the expectation, which for abortive headache treatment should be the full relief of pain within 2 hours of treatment.

Tension Headache

The essential feature of tension headache is the low intensity of the headache and, hence, its responsiveness to simple analgesics (vide supra). Its occurrence is so common that tension headaches can be considered part of life for many, with hardly anybody exempt from them. Its low intensity level and responsiveness to simple analgesics makes them manageable to the sufferer, even when occurring frequently. However, they are not without biological significance, which, in the author’s opinion, lies in its relation to fatigue. Although often triggered by stress or tension, the biological trigger of tension headache is fatigue. Fatigue indicates the depletion of energy and is, as a bodily signal, equally often ignored as headache. When fatigue is ignored, headache is the signal that follows. Apart from stress or tension and fatigue, headache can be triggered by an unlimited list of factors, internal, physical or mental, or external. Stress or tension, fatigue, lack of sleep, and not eating in time are the most common general headache triggers, acknowledged by more than 70% of those having headaches regularly [1].

Apart from its low intensity level, tension headache does not have any specific features. Although generally bilateral in location, affecting the forehead, back of the head, or the head as a whole, they are occasionally unilateral. As a result of their low intensity, they do not affect, to any extent, the ability to function or the functioning of other systems in the body. Hence, increased sensitivity of the senses, such as photophobia, phonophobia, and osmophobia, is absent or mild, if present, and gastrointestinal symptoms, such as nausea or vomiting, are absent. Sometimes a phenomenon that we consider specific for migraine, such as a scintillating scotoma, can precede tension headache and the following case histories are examples thereof.

A 26-year-old woman has had headaches since age 15 years, occurring 5-6 times per year, and lasting for 20-30 minutes. They are mild in intensity, not associated with any other symptoms, and resolve without treatment. The headaches are preceded by a visual disturbance that also lasts for 20-30 minutes. It is located on one or the other side of vision with a preference for the right and consists of a bright white spot, surrounded by flickering zigzag lights. The headaches are located in the anterior vertex and temple, on one side or the other, and usually on the side opposite the preceding visual disturbance.

A 40-year-old woman experiences a series of headaches once every couple of years, 3-4 in the course of a week. The headaches are preceded by a visual disturbance in the right or left visual field but most commonly on the left. It commences as a horizontal zigzag line, which develops into a round area surrounded by light. In the center of the round area, vision appears erased. The visual disturbance lasts for ½ hour after which it gets smaller and slowly fades away. The headaches are mild, located in the anterior vertex, and last for several hours, not associated with any other symptoms. A 62-year-old woman has regularly experienced headaches for almost 40 years, lately once per week. The headaches are mild in intensity and not associated with any other symptoms. They are located across the forehead and last for about 1 hour, resolving without treatment. The headaches are preceded by a visual disturbance that also lasts for about 1 hour. It commences as blurriness in which colorful waves develop that gradually move to the left. The waves are followed by an arcade of bright yellow lines, with the opening to the center. The arcade occurs in the periphery of the left visual field and gradually fades away after the headache sets in.

Frequency is also not a feature of tension headache and, hence, it can vary tremendously from very occasionally to daily. It is not determined by threshold, as it is often assumed, but frequent headache is due to the persistence of triggers, particularly fatigue. For reasons that are either related to sleep or are metabolic or endocrine in nature, fatigue can be persistent and, thus, can be associated with persistent headaches. Stress or tension is generally not persistent but when it is, it results in fatigue through anxiety, depression, and insomnia, which then tends to be persistent. Common metabolic causes of fatigue are anemia and iron deficiency and a not uncommon endocrine cause is hypothyroidism. Chronic tension headache characterized by persistent low-grade headache is a manifestation of hypothyroidism in about 30% of patients [2]. If such persistent low-grade headache is associated with persistent nausea, the nausea is not from the headaches but from associated gastritis, which is not all that rare and is often secondary to regular, if not frequent, NSAID intake.

Migraine Aura

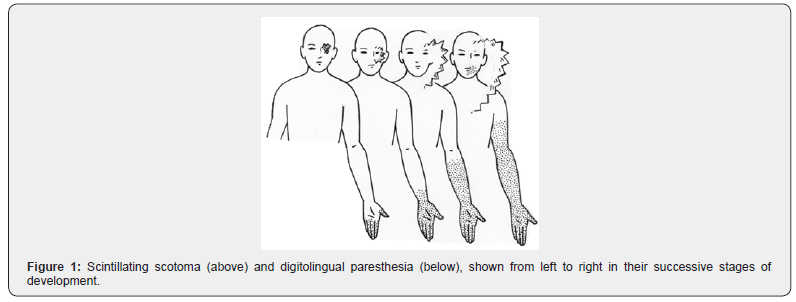

The migraine aura is the introduction to migraine because its diagnosis used to be considered only when the headaches are preceded by transient focal neurological symptoms. These symptoms are almost always visual in nature but sometimes they are somatosensory and, occasionally, they involve speech. The following case histories are typical presentations of the visual migraine aura, also referred to as scintillating scotoma, fortification spectra, or teichopsia. It is schematically shown in Figure 1, along with the somatosensory disturbance, referred to as digitolingual paresthesia or cheiro-oral syndrome.

A 21-year-old woman has had headaches since age 10-11 years. They occur 2-3 times per month, last for 6-7 hours, and are located in the forehead on one side or the other without preference. The headaches are throbbing in nature and severe to the extent of fully incapacitating her. They are associated with nausea, vomiting, photophobia, and phonophobia. The headaches are always preceded by a visual disturbance, which lasts for 20-30 minutes. It occurs on one side or the other, also without preference, commencing near the center of vision as blurriness. The blurriness gradually expands into a semicircle, bordered by flashing zigzag lines, moving peripherally while vision recovers centrally. It ultimately disappears by moving outside of the field of vision. Headache starts as the disturbance disappears, always on the opposite side.

A 47-year-old woman has had headaches since age 19 years, with a gradual increase in frequency to once or twice per week, lasting for 1-3 days. They are always located on the right and extend from the forehead, over the vertex, into the back of the head. The headaches are moderate or severe in intensity, throbbing in nature, and associated with photophobia and, when severe, also with nausea. Two to four times per year, they are preceded by a visual disturbance, followed by headache after 5-10 minutes. From 1997 to 2001, she had the visual disturbance 13 times, of which six occurred on the left and seven on the right, all followed by right-sided headache. Three times the visual disturbance started during sleep and was present on awakening in the morning. Ten times it came on during the day, allowing her to time it from the beginning to the end. The average duration of the 10 visual disturbances that came on during the day was 25.2 minutes (range: 22-29 minutes). This translates into a propagation rate of the underlying phenomenon of 2.8 mm/min, assuming the anteroposterior length of the striate area to be approximately 70 mm. The visual disturbance consists of an arch of wavy zigzag lines, which gradually enlarges as the disturbance moves outward, followed as an afterimage by gray swirling. In addition, there are spots of missing vision, which appear before, during, or after the arch of wavy zigzag lines.

A 69-year-old woman experienced two series of headaches, each lasting for 5-7 days during which the headaches occurred daily, once per day. They always commence with a visual disturbance, lasting for 20-60 minutes, and consisting of a small squiggly line in the periphery of the left visual field. The line subsequently develops into a crescent of zigzag lines, which gradually expands to the right. With the expansion, the zigzag lines, which are colorful, gradually increase in size. The visual disturbance expands across the entire field of vision, ultimately reaching the periphery of the right visual field. It is immediately followed by headache, which is almost instantaneously severe in intensity. The headaches are located in the right temple as a steady pain, lasting for the remainder of the day. They are associated with anorexia and photophobia. As mentioned, sometimes the visual migraine aura is followed by the somatosensory disturbance and, occasionally, the latter is followed by a disturbance of speech. Occasionally, the somatosensory disturbance occurs by itself and the following are examples of these relatively rare presentations of the migraine aura.

A 26-year-old woman has had headaches for 4 years, occurring 2-3 times per year, generally after playing sports. They are located in the left frontoparietal area, throbbing in nature, and lasting for 1 day, associated with nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, photophobia, and irritability. The headaches are preceded by a bright spot in the right visual field, which disappears after 15 minutes to be followed by tingling numbness in the right cheek. It is, in turn, followed by tingling in the fingers of the right hand, which ascends over 15 minutes to involve the forearm to the level of the elbow. Then tingling occurs in the toes of the right foot, ascending over a similar period of time to the level of the knee. She subsequently has difficulty speaking for 15 minutes in the sense that she knows what she wants to say but says something totally different

A 37-year-old man has had headaches since the age of 9 years, gradually increasing in frequency. They are always preceded by tingling in the fingers of a hand, which gradually moves upward and in 10 minutes involves the entire arm. After reaching the shoulder, the tingling goes downward along the trunk to ultimately involve the whole leg as well. The whole process takes about 30 minutes and may also be associated with difficulty expressing words. As the symptoms resolve, headache develops in both temples, lasting for 1-3 days. The headaches are severe and incapacitating, associated with pallor, nausea, vomiting, photophobia, and phonophobia.

A 39-year-old woman has had headaches since her teens, occurring once per week, and lasting for 1 day. They are located across the forehead and in the temples and are throbbing in nature. The headaches are associated with photophobia and phonophobia. Six times per year, they are preceded by a visual disturbance, consisting of a pattern of gray zigzag lines in the left upper quadrant. It lasts for about 20 minutes and is followed, within 15 minutes, by a sensation of numbness in the fingers of the left hand. The numbness subsequently extends into the forearm and then also the left side of the face becomes numb, starting in the nose area and gradually expanding to the mouth, tongue, and throat. The spread of the numbness also takes about 20 minutes and is occasionally followed by a difficulty finding words before headache ensues.

Spreading Cortical Depression

On the basis of experiments with the vasodilators, amyl nitrate [3,4] and carbon dioxide [5], it was initially believed that the mechanism underlying the migraine aura is that of cerebral vasoconstriction. However, now we know, based on Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) studies, that the underlying mechanism is a phenomenon akin to cortical spreading depression [6,7]. Here it concerns a wave of short-lasting neuronal excitation that is followed by prolonged depression of corticoneuronal activity, which travels over the cerebral cortex at the rate of 2-5 mm/min [8,9]. How this phenomenon causes headache is an enigma and, in fact, it may not. There is no evidence that, indeed, it does, and the assumption is purely based on the often-sequential occurrence of the aura and headache. However, temporal relation does not necessarily indicate causality, although the human brain seems programmed to consider such relations as if they did. Parallel, rather than sequential, occurrence of the mechanisms related to the aura and headache of migraine has been proposed [10,11].

The question whether the migraine aura mechanism can be causative of the headache will be addressed later when headache mechanisms are discussed. The question that remains here is what triggers the migraine aura. There is nothing that seems to bring on the somatosensory migraine aura, other than the mechanism underlying the visual aura traveling anteriorly to also involve the somatosensory cortex overlaying the post-central gyrus. When the somatosensory migraine aura occurs by itself, as it is sometimes the case, nothing in particular seems to bring it on. The speech disturbance occurs when the migraine aura mechanism travels even further forward, that is, from the post-central cortex to the precentral motor cortex. In contrast, the visual migraine aura can be triggered by visual stimulation, especially in combination with fatigue, which can be by exercise. Especially strobe visual stimulation can bring it on but only in susceptible individuals, who comprise less than 2% of the general population. This is also the population prevalence of migraine if the condition is only considered when the headaches are preceded by transient focal neurological symptoms of a visual nature. In the adult population of 15-64 years, the last-year prevalence of headache with a warning of major visual symptoms, such as fortification spectra or scotomata, has been shown to be 1.8% [12] and in the pediatric population of 10-16 years, 0.4% [13].

Certain cells in the body depend for their functioning on the processes of depolarization and repolarization. These include brain cells, nerve cells and heart, skeletal, and smooth muscle cells. It is a general misconception that these cells need energy to become active, which means to depolarize their cell membranes. Instead, they need energy to undo their activity, that is, to repolarize their cell membranes. When it comes to repolarization, relaxation occurs when it concerns cells with contractile elements, such as heart, skeletal, and smooth muscle cells. Hence, it is the repolarization phase of muscle contraction that is susceptible to interferences of energy metabolism. This is illustrated by the Electrocardiographic (ECG) changes that occur with ischemia in the second phase of the contractile cycle of the heart, that is, the ST segment, in terms of T-wave inversion and ST-segment depression. Ischemia leads to hypoxia and the lack of oxygen interferes with energy metabolism, which is to a great extent an oxygen dependent process.

With visual stimulation, the visual cortex needs more energy to undo its activity and with fatigue, a state of relative energy depletion, either spontaneous or caused by exercise, the visual cortex relies on a phenomenon akin to spreading cortical depression in order to shut itself off. Migraine aura symptoms probably occur as commonly without headache as they are followed or accompanied by headache. They often occur first or at increased frequency during pregnancy and may be negatively affected by beta-blocker therapy. Both situations can be associated with decreased energy metabolism related to thyroid function. During pregnancy, thyroid function increases as a result of the placental hormone, Human Chorionic Gonadotropin (hCG), stimulating thyroid gland activity. However, if the thyroid gland has limited capacity to respond, a state of relative hypothyroidism results, negatively impacting energy metabolism. Beta-blockers inhibit the conversion of thyroxine (T4) to triiodothyronine (T3) and, hence, the activation of thyroid hormone. Some betablockers do this more potently than others and particularly propranolol has this effect. Hence, the medication is also used for the symptomatic treatment of hyperthyroidism for which it is very effective. While hypothyroidism can also negatively affect headaches (vide supra), beta-blockers can do the opposite if they lack partial agonist or intrinsic sympathomimetic activity [14]. These are the beta-blockers that, in randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies, have been shown to be effective in preventing migraine headache. They are, in alphabetical order, atenolol, bisoprolol, metoprolol, nadolol, propranolol, and timolol. The above-mentioned effects may result in a differential effect of the medications on the migraine aura and migraine headache, in which the former worsens and the latter improves.

Migraine Headache

Migraine headache used to be called sick headache and was brought into the migraine fold in the first half of the last century. It was called common migraine to contrast it with classic migraine, in which the headache is preceded or accompanied by transient focal neurological symptoms (vide supra). The names were subsequently changed to migraine without aura and migraine with aura, respectively. With the addition of sick headache, as common migraine or migraine without aura, the last-year prevalence of migraine in the general adult population increased significantly, that is, from less than 2%12 to over 12% [15]. The isolated occurrence of migraine aura, that is, without headache, is now referred to as migraine aura without headache. The association of migraine aura with tension headache has been referred to as typical aura with headache, with or without migraine characteristics [16].

Headache Amplifier

Low headache intensity is the essential feature of tension headache, while high headache intensity is the essential feature of migraine. As the triggers of both types of headache are basically the same1, headache amplification must be at work and has been proposed as the basic feature of migraine [17,18]. It is this particular feature of migraine that drives headache duration and associated symptoms, the latter being plentiful due to a derangement in function of several systems in the body. In fact, there is not a system that is not affected by the high intensity headaches of migraine. It affects the nervous system, causing anxiety, depression, and increased sensitivity of the senses; it affects the ophthalmological system, causing blurred vision and, sometimes, tearing of the eye(s); it affects the ear-noseand- throat (ENT) system, occasionally causing nasal congestion or rhinorrhea; it affects the cardiovascular system, causing tachycardia, hypertension, orthostatic hypotension, and, through peripheral vasoconstriction, pallor as well as cold hands and feet; it affects the gastrointestinal system, causing anorexia, nausea, sometimes vomiting, and occasionally diarrhea; it affects the muscular system by causing muscle tightness, especially in the neck, shoulders, and upper back and sometimes also in the jaws.

Whereas the location of tension headache is generally bilateral, that of migraine is unilateral in at least two thirds of sufferers and, hence, the name migraine, derived from the Greek hemicrania. The unilaterality is typically alternating, with the headache sometimes occurring on the left and sometimes on the right, although often with a preference for one side or the other. Fixed lateralization with the headaches always occurring on the same side is uncommon in migraine and can never be taken for granted. It indicates that something else is going on that causes the fixed lateralization and this can either be an intracranial or extracranial process. Such an intracranial process can be a vascular anomaly, such as an Arteriovenous Malformation (AVM) or a space-occupying lesion (neoplasm, hematoma, abscess, etcetera). Extracranially, the cause of fixed headache lateralization can be spasm of the ipsilateral posterior cervical muscles or of the muscles of mastication, particularly the masseter muscle, chronic ipsilateral rhinosinusitis, or intranasal contact on the side of the lateralization. For reasons not really known, unilateral location, as opposed to bilateral location, tends to be associated with more intense pain and this seems to be equally true for headache and face pain [19]. Regarding face pain, this is the case whether the pain is predominantly central in location in the nose-cheek area or predominantly peripheral in the jaw. Headache intensity also tends to be more intense with a more anterior location, traveling from the back of the head, through the side of the head and temple, to the eye. Particularly pain located in the eye is often intense and described as a sharp steady pain that feels as if there is a nail stuck in the eye or as if the eyeball is being pushed out of the socket. This in contrast to pain felt in the temple, which tends to be described as a dull throbbing pain that can usually be relieved somewhat by exerting pressure on the painful area (Parry’s compression test).

Headache Frequency

In contrast to high headache intensity, headache frequency, whether low or high, is not a specific feature of migraine either. Hence, like tension headache, migraine can vary tremendously in frequency from a rare occurrence, especially seen in migraine with aura, to occurring daily, as is often the case in chronic migraine. The International Headache Society makes the distinction between episodic and chronic migraine based on overall headache frequency16. It adds up the total number of headache days per month, migraine or otherwise, and if the sum total is less than half the month, episodic migraine is diagnosed; otherwise, the condition is referred to as chronic migraine. However, if headache frequency is not a feature of migraine, what determines the difference in headache frequency between episodic and chronic migraine? The clue to the answer of this question lies in the differential benefit of Botox® in episodic versus chronic migraine. Through the so-called PREEMPT studies [20,21]. the medication has been demonstrated to be effective in the preventive treatment of chronic migraine, which led to the inclusion of this particular migraine condition in its US labeling. Such proof is absent for episodic migraine despite half a dozen randomized, doubleblind, placebo-controlled studies conducted by the manufacturer, Allergan (Dublin, Ireland). Hence the FDA-approved labeling of the medication contains the following statement BOTOX® (onabotulinumtoxinA) is a prescription medicine that is injected to prevent headaches in adults with chronic migraine who have 15 or more days each month with headache lasting 4 or more hours each day in people 18 years or older. It is not known whether BOTOX® is safe or effective to prevent headaches in patients with migraine who have 14 or fewer headache days each month (episodic migraine).

The differential effect of Botox® on episodic versus chronic migraine suggests that the medication does not treat migraine per se because, otherwise, it would be effective in both. However, if Botox® does not treat migraine, then what does it treat to improve the headaches in chronic migraine? The clue to the answer of this question comes from the co-morbidities with which chronic migraine, in contrast to episodic migraine, tends to be associated. Hence, the associated co-morbidities may be a much more important distinguishing feature between episodic and chronic migraine than the total number of headache days per month. For chronic migraine, it would also make the relevant conditions more than co-morbidities, that is, concomitant but unrelated (italicized by author) pathological or disease processes (The American Heritage® Medical Dictionary).

Co-morbidities

Headache, including migraine, is more common in women than in men (last-year prevalence: 2:1), migraine, with its high intensity headaches, much more so than tension headache with its low intensity headaches (last-year prevalence: 2.5:1 versus 1.4:1)[22]. In women, the first onset of headache is often related to reproductive events, such as the onset of menstruation in the early teens, the use of estrogen-containing hormonal contraceptives in the late teens or adolescence, and pregnancy, rather after than during, in early and mid-adulthood [23]. The estrogen hormonal cycle related to the menstrual cycle is the trigger of often intense and longer lasting headaches, either before menstruation, mid-cycle at the time of ovulation, and/or at the tail end of menstruation. The worsening of headache in relation to the menstrual cycle is as common in chronic migraine as is the occurrence of headache in relation to the menstrual cycle in episodic migraine. However, menstrual-cycle disorders in general, that is, oligomenorrhea, polymenorrhea, and irregular cycle, as well as the menstruation disorder of dysmenorrhea, have been demonstrated to be significantly more common in chronic than in episodic migraine [24]. A particularly severe cause of dysmenorrhea, that is, endometriosis, has also been shown to be more common in chronic than in episodic migraine [25,26]. However, not only gynecological conditions are more common in chronic than in episodic migraine but also allergies, asthma, hypertension, and hypothyroidism [27]. While, in subsequent studies, hypertension and hypothyroidism were not confirmed as associated co-morbidities of chronic migraine [24,28] a large Italian study added the following conditions insomnia and constipation as well as psychiatric, gastrointestinal, musculoskeletal, ocular, genitourinary, hematologic, cerebrovascular, and cardiac disorders [28]. They did not describe any of these disorders in detail but common conditions comorbid with chronic migraine, apart from insomnia, constipation, and dysmenorrhea are, in random order: anxiety, depression, fatigue, myalgias of various sorts, including myofascial Temporomandibular disorder (TMD), cervicalgia, and lumbago, fibromyalgia, acid reflux (GERD), chronic nausea, Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS), and menstruation and menstrual cycle disorders.

Of course, the above listed co-morbidities are not unique to the chronic migraine sufferer and seem to be shared by those who suffer chronically in general. In addition to what they suffer from specifically and present with in practice, they tend to have a multitude of medical and psychiatric conditions. The only diagnosis that captures this multitude of conditions was somatization disorder, as defined in DSM III [29] and IV [30]. However, in DSM V, published in 2013, this diagnosis was abandoned in favor of somatic symptom disorder, which emphasizes excessive thought, rather than unexplained medical conditions [31]. It is the author’s opinion, however, that these individuals have a systemic endocrine-metabolic disorder rather than a psychiatric illness, with the metabolic component centering around energy metabolism [17,18]. It is not a disorder with a single etiology and, hence, not a disease, and its etiology can be endocrine or metabolic, congenital or acquired. The disorder is, therefore, more appropriately referred to as a syndrome, in this case, systemic endocrine metabolic syndrome or SEMS.

The component of SEMS that is proposed to account for the high headache frequency of chronic migraine is its impact on the skeletal muscular system or, more specifically, on the muscles of the head, neck, and shoulder(s), that is, the craniocervical muscles, and sometimes on those of the jaw(s), that is, the muscles of mastication. This is where the Botox® injections are performed for the preventive treatment of chronic migraine and the medication is well known for its prolonged muscle-relaxant benefit. However, chronic migraine is not part of SEMS, which is associated with chronic migraine only if the genetically-determined and inherited headache amplifier of migraine is present. Otherwise, chronic tension headache may be its accompaniment, as is illustrated by the following case history.

A 34-year-old woman developed pressure in her temples, tight jaws, and pain in her shoulders following pregnancy. Apart from these complaints, she has long (8-9 days) and heavy periods (hypermenorrhea), which were very painful from menarche until the pregnancy (dysmenorrhea). The periods occur regularly and on a monthly basis but, nevertheless, she has infertility. Her epigastric area is tender, suggestive of gastritis, and she has constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome (IBS-C). She also has anxiety. She sleeps well and gets 7-8 hours of sleep per night but, nevertheless, feels tired during the day as well as weak in general. However, if the genetically determined and inherited migraine headache amplifier is present, the presentation is that of chronic migraine, as in the following case histories.

An 18-year-old woman has had migraine since age 11 years (menarche at age 12). The headaches occur daily and usually come on during the day but not at any particular time. They are moderately severe in intensity (7-8/10) but are severe (9- 10/10) once or twice per week for 1-2 days. The headaches are located in the forehead, eyes, temples, and back of the head. They are throbbing in nature and made worse by physical activity. The headaches are not preceded by aura. They are associated with photophobia and phonophobia and when severe, also with nausea. Apart from the headaches, she has insomnia and gets, on average, only 5 hours of sleep per night. As a result, she feels tired during the day and rates her energy level as 2/10. She has anxiety, depression, and Attention Deficit Disorder (ADD). She has acid reflux (GERD) and diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome (IBS-D); she used to be constipated. Her neck and shoulder muscles are tight and sore.

A 20-year-old woman has had migraine since age 13 years (menarche at age 12). The headaches occur almost daily and are often present, at moderate intensity (5/10), on awakening in the morning. Approximately half of the week, they increase in intensity to become severe (8/10) by early afternoon; otherwise they remain moderate. The headaches are generalized in location but, when severe, concentrate in the left forehead and eye. They are throbbing in nature and made worse by physical activity. The headaches are not preceded by aura. They are associated with photophobia and phonophobia and when severe, also with nausea and, on average, twice per month with vomiting. Apart from the headaches, she has insomnia and gets, on average, 6-7 hours of interrupted sleep per night. As a result, she feels tired during the day and rates her energy level as 6/10. She has depression as well as irritable bowel syndrome, alternating with constipation and diarrhea (IBS-M). Her periods occur twice per month (polymenorrhea), last for 7 days and are heavy (hypermenorrhea) and very painful (dysmenorrhea). Her neck and shoulder muscles are tight and sore and she has had low-back pain since childhood.

Neurogenic Inflammation

The clue to the nature of the genetically determined and inherited headache amplifier of migraine can be found in the novel class of preventive medications for the treatment of episodic and chronic migraine. These medications are monoclonal antibodies against the CGRP (calcitonin gene-related peptide) ligand (eptinezumab, fremanezumab, and galcanezumab) or the CGRPreceptor (erenumab) [32]. They block the biological effects of CGRP of which those that constitute part of so-called neurogenic inflammation are best known [33]. Neurogenic inflammation is a mechanism through which activation of nociceptive C and A nerve fibers leads to inflammation of peripheral tissue. The inflammation is mediated by the release of neuropeptides, which include, apart from CGRP, neurokinin A and substance P. Whereas substance P is a potent inflammatory agent, increasing microvascular permeability and allowing plasma extravasation, CGRP is a very potent vasodilator. Vasodilation is a prominent part of the migraine headache mechanism as is evidenced by the fact that vasoconstrictor agents, such as caffeine, ergots, and triptans, are the most potent abortive migraine medications.

It is proposed that the genetically determined and inherited migraine headache amplifier resides in the threshold at which the mechanism of neurogenic inflammation is activated by whatever triggers headache. The impact of migraine genetics on the neurogenic inflammation threshold is more likely to be similar to that of a dimmer than that of an on-off switch, accounting for the variability in headache intensity expression. In those migraineurs in whom the threshold is still relatively high, headache intensity will be more in the lower high-intensity range than in those in whom the threshold is low, who will suffer from the most intense migraine headaches. However, not only the threshold for neurogenic inflammation is important but also the trigger, with estrogen withdrawal seemingly the most potent one, causing the most intense and prolonged migraine headaches.

Finally, which peripheral tissues are affected by the neurogenic inflammation of which the activation causes, in part or in whole, the migraine headache? Until the first half of the twentieth century, the migraine headache was thought to be due to dilation of cerebral arteries. However, dampening of cerebral artery pulsation by increasing intrathecal pressure did not relieve migraine headache3 and ergotamine, the first specific abortive migraine medication available, did not impact cerebral blood flow [34]. It was subsequently shown that ergotamine potently constricts extracranial arteries and that this vasoconstrictor effect parallels headache relief [35]. A mild vasoconstrictor effect was also demonstrated on the meningeal or dural arteries and, since the late twentieth century, the pachymeninx or dura matter has been thought to be the site of action when it comes to migraine headache [36]. Inflammation, rather than vasodilation, has been implicated here and substance P, rather than CGRP, as the prominent neuropeptide involved. However, drug development focusing on substance P has not led to progress in migraine treatment, whether abortively or preventively [37]. This, in contrast to drug development focusing on CGRP, which generated the effective and well tolerated CGRP(-receptor) antibodies for preventive migraine treatment mentioned above [32]. Along with the shift from substance P to CGRP comes the shift from inflammation to vasodilation and, along with that, the shift from meningeal or dural to extracranial. In this context, it is important to remember that the only human tissue in which vasodilation and inflammation have been demonstrated to occur in relation to the migraine headache is the extracranial tissue[38]. In addition, where CGRP release has been documented during migraine headache, it is in blood drawn from the external jugular vein, which drains the cranial, non-cerebral tissues of which the pachymeninx or dura matter is but a small component [39].

Conclusion

a. Rather than migraine aura, the determining feature of migraine is high intensity level headache.

b. The mechanism of the migraine aura is a phenomenon akin to cortical spreading depression, which is not a trigger of headache, migraine or otherwise.

c. Migraine headaches in their onset and their occurrence are triggered by what causes headache in general; hence, migraine triggers do not exist but only headache triggers.

d. The mechanism of the migraine headache is neurogenic inflammation, with CGRP_ mediated vasodilation being more important than substance P-mediated inflammation.

e. The essence of migraine lies in the threshold at which the mechanism of neurogenic inflammation is activated by whatever triggers headache, which is genetically determined and inherited.

f. The peripheral tissue in which the mechanism of neurogenic inflammation occurs to cause the migraine headache, in part or in whole, is extracranial rather than meningeal or dural.

g. The high headache frequency in chronic migraine is not a feature of migraine per se but of a Systemic Endocrine Metabolic Syndrome (SEMS) that can be endocrine or metabolic, congenital or acquired.

h. Migraine is not a disease, neurological or otherwise; it is a genetically determined and inherited headache amplifier.

References

- Spierings ELH, Ranke AH, Honkoop PC (2001) Precipitating and aggravating factors of migraine versus tension-type headache. Headache 41(6): 554-558.

- Moreau Th, Manceau E, Giroud Baleydier, Dumas R, Giroud M (1998) Headache in hypothyroidism. Prevalence and outcome under thyroid hormone therapy. Cephalalgia 18(10): 687-689.

- Schumacher GA, Wolff HG (1941) Experimental studies on headache: A. Contrast of histamine headache with the headache of migraine and that associated with hypertension. B. Contrast of vascular mechanisms in preheadache and in headache phenomena of migraine. Arch Neurol Psychiat 45: 199-214.

- Hare EH (1966) Personal observations on the spectral march of migraine. J Neurol Sci 3(3): 259-264.

- Marcussen RM, Wolff HG (1950) Studies on headache: 1. Effects of carbon dioxide-oxygen mixtures given during the preheadache phase of the migraine attack. 2. Further analysis of pain mechanisms in headache. Arch Neurol Psychiat 63: 42-51.

- Milner PM (1958) Note on a possible correspondence between the scotomas of migraine and spreading depression of Leã Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 10(4): 705.

- Hadjikhani N, Sanchez del Rio M, Wu O, Schwartz D, Bakker D, et al. (2001) Mechanisms of migraine aura revealed by fMRI in human visual cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98(8): 4687-4692.

- Leão AAP (1944) Spreading depression of activity in the cerebral cortex. J Neurophysiol 7: 359-390.

- Grafstein B (1956) Mechanism of spreading cortical depression. J Neurophysiol 19(2): 154-171.

- Spierings ELH (1988) Recent advances in the understanding of migraine. Headache 28(10): 655-658.

- Spierings ELH (2004) The aura-headache connection in migraine. A historical analysis. Arch Neurol 61(5): 794-799.

- Clarke GJR, Waters WE (1974) Headache and migraine in a London general practice. In: Waters WE (ed). The epidemiology of migraine. Boehringer Ingelheim, Bracknell-Berkshire 14-22.

- Small P, Waters WE (1974) Headache and migraine in a comprehensive school. In: Waters WE (ed). The epidemiology of migraine. Boehringer Ingelheim, Bracknell-Berkshire 59-67.

- Weerasuriya K, Patel L, Turner P (1982) Beta-adrenoceptor blockade and migraine. Cephalalgia 2(1): 33-45.

- Lipton RB, Stewart WF, Diamond S, Diamond ML, Reed M (2001) Prevalence and burden of migraine in the United States: data from the American Migraine Study II. Headache 41(7): 646-657.

- (2013) Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society. The international classification of headache disorders, 3rd edition (beta version). Cephalalgia 33: 629-808.

- Spierings ELH (2017) A perspective on the comorbidities of chronic migraine. OA J Neurol Neurosurg 6(3).

- Spierings ELH (2018) The relation between episodic headache and chronic daily headache (CDH). Annals of Pain Medicine 1: 1001.

- Spierings ELH (2018) Diagnosis and treatment of face pain: a brief guide. Open Access J Neurol Neurosurg 7(5).

- Aurora SK, Dodick DW, Turkel CC, DeGryse RE, Silberstein SD, et al. (2010) Brin MF on behalf of the PREEMPT 1 Chronic Migraine Study Group. OnabotulinumtoxinA for treatment of chronic migraine: results from the double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled phase of the PREEMPT 1 trial. Cephalalgia 30: 793-803.

- Diener HC, Dodick DW, Aurora SK, Turkel CC, DeGryse RE, Lipton RB, Silberstein SD, Brin MF on behalf of the PREEMPT 2 Chronic Migraine Study Group. OnabotulinumtoxinA for treatment of chronic migraine: results from the double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled phase of the PREEMPT 2 trial. Cephalalgia 30: 804-814.

- Rasmussen BK, Jensen R, Schroll M, Olesen J (1991) Epidemiology of headache in a general population – a prevalence study. J Clin Epidemiol 44(11): 1147-1157.

- Karpouzis KM, Spierings ELH (1999) Circumstances of onset of chronic headache in patients attending a specialty practice. Headache 39(5): 317-320.

- Spierings ELH, Padamsee A (2015) Menstrual-cycle and menstruation disorders in episodic versus chronic migraine: an exploratory study. Pain Medicine 16(7): 1426-1432.

- Tietjen GE, Conway A, Utley C, Gunning WT, Herial NA (2006) Migraine is associated with menorrhagia and endometriosis. Headache 46(3): 422-428.

- Tietjen GE, Bushnell CD, Herial NA, Utley C, White L, et al. (2007) Endometriosis is associated with prevalence of comorbid conditions in migraine. Headache 46(3): 1069-1078.

- Bigal ME, Sheftell FD, Rapoport AM, Tepper SJ, Lipton RB (2002) Chronic daily headache: identification of factors associated with induction and transformation. Headache 42(7): 575-581.

- Ferrari A, Leone S, Vergoni AV, Bertolini A, Sances G, et al. (2007) Similarities and differences between chronic migraine and episodic migraine. Headache 47(1): 65-72.

- (1980) American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd American Psychiatric Association, Washington, DC, USA.

- (1994) American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th American Psychiatric Association, Washington, DC, USA.

- (2013) American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th American Psychiatric Association, Washington, DC, USA.

- Spierings ELH (2018) Monoclonal CGRP ligand/receptor antibodies for the preventive treatment of episodic and chronic migraine. Ann Pain Medicine 1: 1005.

- Foreman JC (1987) Peptides and neurogenic inflammation. Br Med Bull 43(2): 386-400.

- Hachinski VC, Norris JW, Edmeads J, Cooper PW (1978) Ergotamine and cerebral blood flow. Stroke 9(6): 594-596.

- Graham JR, Wolff HG (1938) Mechanism of migraine headache and action of ergotamine tartrate. Arch Neurol Psychiat 39: 737-763.

- Markowitz S, Saito K, Moskowitz MA (1987) Neurogenically mediated leakage of plasma protein occurs from blood vessels in dura mater but not brain. J Neurosci 7(12): 4129-4136.

- Spierings ELH (2002) Inhibition of neurogenic inflammation in abortive migraine treatment. In: Spierings ELH, Sánchez del Río M (eds). Migraine: a neuroinflammatory disease? Birkhäuser Verlag, Basel133-143.

- Chapman LF, Ramos AO, Goodell H, Silverman G, Wolff HG (1960) A humoral agent implicated in vascular headache of the migraine type. Arch Neurol 3: 223-229.

- Goadsby PJ, Edvinsson L, Ekman R (1990) Vasoactive peptide release in the extracerebral circulation of human during migraine headache. Ann Neurol 28(2): 183-187.