Efficacy of Immediate Perampanel Oral Loading in Convulsive Status Epilepticus: A Single-Center Experience of Consecutive 22 Patients

Atsushi Ishida*, Seigo Matsuo, Keizoh Asakuno, Haruko Yoshimoto, Hideki Shiramizu, Masataka Kato, Yusuke Sasaki, Ko Nakase and Tomokatsu Hori

Department of Neurosurgery, Moriyama Memorial Hospital, Japan

Submission: June 10, 2020; Published: July 08, 2020

*Corresponding author: Atsushi Ishida, Department of Neurosurgery, Moriyama Memorial Hospital 4-3-1 Kitakasai, Edogawa, Tokyo, Japan

How to cite this article: Atsushi I, Seigo M, Keizoh A, Haruko Y, Hideki S, et al. Efficacy of Immediate Perampanel Oral Loading in Convulsive Status Epilepticus: A Single-Center Experience of Consecutive 22 Patients. Open Access J Neurol Neurosurg. 2020; 13(5): 555874. DOI: 10.19080/OAJNN.2020.13.555874.

Abstract

Convulsive Status epilepticus (CSE) is a relatively common neurological emergency with high morbidity and mortality and should be stopped as soon as possible to avoid cerebral damage. Despite novel anti-epileptic drugs, its control rate has not been changed sufficiently. Perampanel (PER) is an antagonist of alpha-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptor which is identified as a potential therapeutic target for the treatment of SE. Data on the efficacy of PER in treatment of SE in humans are still insufficient due to lack of homogenous study with high doses and very early administration of the drug. We retrospectively analyzed treatment response, the outcome of all patients with CSE in our hospital who received 8mg of PER oral loading from January 2018 to June 2019. Twenty-two consecutive patients with CSE were included. The etiology and the seizure types were wide-ranging. Fifteen out of 22 patients suffering from CSE responded to PER oral loading (68%) and they became seizure-free within 24 hours. The responders’ outcome after 30 days was significantly better than that of non-responders. There were no severe side effects but minor somnolence which was acceptable for emergent cases. This should be applied to the standard treatment protocol of CSE.

Keywords: perampanel oral loading; convulsive status epilepticus; single-center experience; AMPA receptor; very early administration

Abbreviations: CSE: Convulsive Status epilepticus; PER: Perampanel; AED: Anti-Epileptic Drug; EEG: Electroencephalography; AMPA: α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid; BZD: Benzodiazepine; ASL: Arterial Spin-Labeling; CBF: Cerebral Blood Flow; GOS: Glasgow Outcome Scale; NCSE: Non Convulsive SE

Introduction

Status Epilepticus (SE) is a severe condition characterized by high mortality and morbidity. If the seizure continues longer than five minutes, it is defined as early SE [1]. If the seizure is persistent despite therapy with benzodiazepines, it is then defined as established SE [1]. Refractory SE (RSE) is defined as the seizure that continues longer than one or two hours despite therapy with intravenous anti-epileptic drugs such as phenytoin, phenobarbital [1]. General anesthesia is recommended for patients with RSE under electroencephalography (EEG). Despite the growing use of newer Anti-Epileptic Drugs (AEDs) in SE over the last decade, it may increase the risk of SE refractoriness and new disability at hospital discharge [2]. Perampanel (PER) is a novel AED which acts as a non-competitive α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) receptor antagonist to reduce glutamate-mediated postsynaptic excitation [3]. Previous animal studies [4] and a few case reports [5] have suggested that it may be effective to treat SE. However, those reports were highly heterogeneous in terms of doses and institutions [5]. Moreover, PER treatment was not conducted immediately after the onset of SE in those studies [5]. A more clinically homogeneous study with given intervals shorter than 24h had been warranted [5]. In the present study, we investigated the efficacy and safety of PER oral loading (8mg) in a very early stage of SE.

Material and Methods

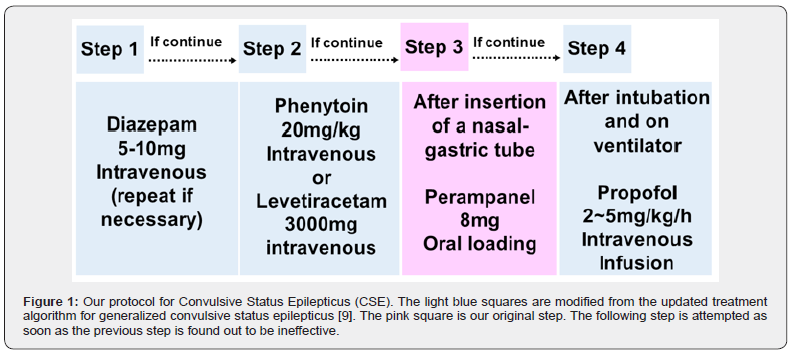

Consecutive SE patients treated with oral loading of PER (8mg) between January 2018 and June 2019 in Moriyama Memorial Hospital, Tokyo, Japan. This study was approved by the ethics committee at Moriyama Memorial Hospital. The patients without prominent motor symptoms (i.e., nonconvulsive SE, NCSE) were not included in this case series; that is, all the patients had convulsive SE (CSE). The PER dose was meticulously determined according to the result of the clinical trials [6]. Adjunctive PER (8 and 12 mg/d) significantly improved seizure control in patients with refractory partial-onset seizures [6]. Safety and tolerability were acceptable at daily doses of PER 4-12 mg [6]. Seizure frequency decreased linearly as predicted PER average steady-state plasma concentrations increased [7]. According to the pharmacokinetics of PER (unpublished clinical trial data), the plasma concentration of PER rises sharply and reaches about 150ng/ml within 30 minutes which is about two times higher than the peak concentration of 2mg oral administration (recommended initial dose of PER). Therefore, we chose 8mg for oral loading expecting SE is controlled within an hour. Patients were treated according to the updated treatment algorithm for generalized CSE in adults and older children [8]. According to the algorithm, if seizures continue despite initial treatment with benzodiazepines (BZDs) and a second-line antiepileptic drug, the patients should be intubated and administered with intravenous propofol [8]. In this study, a nasal gastric tube was inserted, and oral loading of PER was conducted after 2nd line AED (Figure 1). If SE is not controlled despite PER loading, intravenous propofol was administered under intubation (Figure 1).

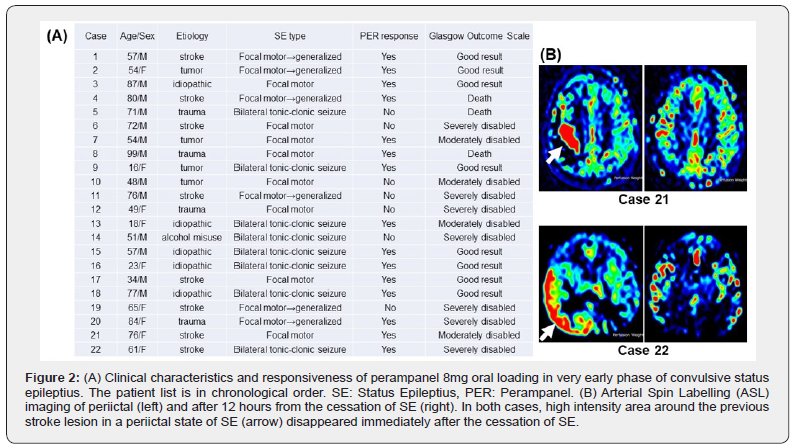

CSE should be terminated as soon as possible no matter what the cause is. In the emergent situations, an MRI study including Arterial Spin-Labeling (ASL) was conducted instead of EEG; which is not always available in an emergency hospital like us. ASL, an MR method for assessing Cerebral Blood Flow (CBF), requires no administration of exogenous tracer or contrast media. Several reports have described that the ASL study is useful for diagnosing and detecting the focus of epilepsy in a preictal state of SE [9]. If a seizure focus was identified from the MRI result and known history, we assumed the patient had SE without an EEG study. Following EEG after the termination of clinical SE was carried out in some patients but no evident epileptic waves were observed. The association between PER responsiveness and Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOS) at 30 days was examined using Fisher’s exact tests (p<0.05). Statistical analysis was performed with the SAS statistical package.

Results

Twenty-two patients (9 women, mean age: 59.5 years) received PER as soon as possible after 2nd line AED failure in SE (Figure 1). The etiology was wide-ranging including stroke (8/22, 38%), tumor (4/22, 18%), head trauma (4/22, 18%) but five cases were of unknown causes. The most frequent CSE type was Focal motor but six of them became generalized. Other patients had Bilateral tonic-clonic seizure from the beginning. These patients with CSE were treated with BZDs immediately after the onset of the seizure. Even if it worked and the seizure stopped, another seizure appeared within a very short period. BZDs were then administered repeatedly in the same dose, but they frequently cause respiratory depression; therefore, up to three times. If the seizure was not completely terminated up to 30 min, 2nd line intravenous AEDs; phenytoin, or levetiracetam were then administered (Figure 1). Phenytoin was effective in some cases but occasionally caused cardiovascular problems, such as bradycardia. Levetiracetam was not effective for CSE in this study. If the seizure still repeated and the duration of the intervals were not extended, 8mg of PER was then orally administered. Time from the onset of CSE to PER oral loading ranged between half an hour and 12 hours. PER was administered earlier in generalized cases and if continued, patients were intubated and propofol was then administered (Figure 1). Even in partial motor cases, CSE has long been known to cause neuronal damage [8]. Therefore, patients were treated following the generalized CSE protocol [8]. For that, PER loading for partial motor cases tended to be later than generalized cases. In the effective cases (PER responders), the seizure gradually became less frequent within an hour and the patients became seizure-free within 24 hours. ASL after SE termination showed the disappearance of the high-intensity area which was apparent during CSE (Figure 2a). Altogether, treatment response was observed in fifteen patients (68%). Once SE was terminated with the oral loading, recurrence was not observed in those cases. No significant side effects nor elevation of liver enzymes were observed as reported in the latest article about PER for SE [10]. There were only minor somnolence and dizziness as an adverse effect after PER oral loading, which quickly resolved despite an ongoing reduced dose of PER treatment. Glasgow outcome scale (GOS) was used as an outcome measure according to the previous studies about PER for SE [10,11]. In this study, eight patients had Good results in the Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOS) after 30 days. There was no Good result from those whose SE was not responsive to the oral loading of PER. Their outcome was unfavorable as Death or Severely disabled (Figure 2b). The outcome of PER responders was favorable (Good result, Moderately disabled) in 11 patients (73%) and unfavorable (Death, Severely disabled) in four patients. On the other hand, the outcome of PER non-responder was favorable in only one patient (14%) and unfavorable in six patients. This is statistically significant (p=0.020). PER responsiveness was not correlated with either etiology nor SE type (Figure 2a).

Discussion

In this study, we report PER oral loading in a very early stage of CSE. PER acts on the AMPA receptor of the post-synaptic neuron, which is completely different from the other available AED. The effects of AMPA receptor antagonists have been investigated in animal models of SE. The effect of PER on BZDresistant SE was studied in a lithium-pilocarpine rat model [4]. PER terminated seizures in all animals at 30 minutes after seizure onset, which suggests that that AMPA receptor antagonists may have a potential in the treatment of SE. As the effective PER dose was reduced when tested in combination with diazepam, the two drugs might act synergistically [4]. In our study, according to the universal algorithm, diazepam was administered first for a couple of times before PER oral loading, the synergistic effect might have augmented the efficacy of PER on SE termination. Based on the preliminary data of the previous studies, Di Bonaventura et al. strongly suggested that start of PER with loading doses higher than 6 mg or dose intervals shorter than 24 h might be considered for future studies to increase the effectiveness of PER in terminate a refractory SE in a shorter period [12]. We meticulously selected the loading dose and finally, 8mg was selected. PER oral loading was attempted only once and further dose-elevation was not studied in our series for the sake of homogeneity. Another group reported that PER was well-tolerated even high doses of PER up to 32mg [11]. Since the miserable outcome of those without SE termination by PER, we should have tried higher doses than 8mg when the first loading was not effective. Elevated liver enzymes were documented in the report especially in the high-dose group [11]. High dose of PER continued for a few days and relatively large numbers of AED were already administered [11]. Since 8mg of PER administration was done only once and previous AEDs were almost none in our study, liver enzyme elevation was not observed. Brigo et al performed a comprehensive and systematic review of the literature to assess the efficacy and tolerability of PER in SE patients [5]. They conclude that the currently available evidence supporting the use of PER in SE is weak and hampered by several confounding factors. The proportion of patients achieving clinical SE cessation varied from 17% to 100%. This was due to the heterogeneity of the studies and further studies should be performed in more clinically homogeneous and larger cohorts in earlier stages of SE, at higher dosages, and intervals shorter than 24 h. In the review, the time from SE onset to PER administration ranged from 9.25 h to 35 days. In our series, PER loading was attempted immediately after the 1st and 2nd lines of AED. Therefore, the time was much shorter than that. The initial PER dose ranged from 2 to 32 mg in the review cases. Again, in our series, the dose was utterly uniform.

The limitation of this study is the lack of enough EEG data; while continuous EEG monitoring was used in the previous studies of PER for SE [10,11]. Those studies included many NCSE cases and they started using PER after a couple of days from the onset. In our study, CSE patients kept having a seizure in front of us and PER was administered within 12 hours; therefore, ictal EEG was not evaluated. Following EEG after the termination of clinical SE was carried out in some patients but no evident epileptic waves were observed. It took a couple of days for cessations of SE after PER administration in those previous studies [10,11]. In our study, PER-responders became seizure-free within 24 hours. It may be explained by the short period from the onset of the seizure until the PER-loading. Although we excluded NCSE from this case series to make this study simple and homogenous, PER loading in a very early phase was quite effective for NCSE patients as well. Together with our results for CSE, PER oral loading is effective for refractory SE without major side effects. When an infusible agent is available shortly, PER will have a pivotal role in the treatment of refractory SE.

Conclusion

We conclude that early PER oral loading is a very effective and well-tolerated treatment for SE. However, larger controlled studies are required to establish this treatment as a standard protocol for SE treatment.

Conflict of Interest

Atsushi Ishida has no conflicts of interest to disclose. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- Shorvon S, Ferlisi M (2011) The treatment of super-refractory status epilepticus: a critical review of available therapies and a clinical treatment protocol. Brain 134(10): 2802-2818.

- Beuchat I, Novy J, Rossetti AO (2017) Newer Antiepileptic Drugs in Status Epilepticus: Prescription Trends and Outcomes in Comparison with Traditional Agents. CNS Drugs 31(4): 327-334.

- Ceolin L, Bortolotto ZA, Bannister N, Collingridge GL, Lodge D, et al. (2012) A novel anti-epileptic agent, perampanel, selectively inhibits AMPA receptor-mediated synaptic transmission in the hippocampus. Neurochem Int 61(4): 517-522.

- Hanada T, Ido K, Kosasa T (2014) Effect of perampanel, a novel AMPA antagonist, on benzodiazepine-resistant status epilepticus in a lithium-pilocarpine rat model. Pharmacol Res Perspect 2(5): e00063.

- Brigo F, Lattanzi S, Rohracher A, Russo E, Meletti S, et al. (2018) Perampanel in the treatment of status epilepticus: A systematic review of the literature. Epilepsy Behav 86: 179-186.

- Nishida T, Lee SK, Inoue Y, Saeki K, Ishikawa K, et al. (2018) Adjunctive perampanel in partial-onset seizures: Asia-Pacific, randomized phase III study. Acta Neurol Scand 137(4): 392-399.

- Gidal BE, Ferry J, Majid O, Hussein Z (2013) Concentration-effect relationships with perampanel in patients with pharmacoresistant partial-onset seizure. Epilepsia 54(8): 1490-1497.

- Betjemann JP, Lowenstein DH (2015) Status epilepticus in adults. Lancet Neurol 14(6): 615-624.

- Matsuura K, Maeda M, Okamoto K, Araki T, Miura Y, et al. (2015) Usefulness of arterial spin-labeling images in periictal state diagnosis of epilepsy. J Neurol Sci 359(1-2): 424-942.

- Ho CJ, Lin CH, Lu YT, Shih FY, Hsu CW, et al. (2019) Perampanel Treatment for Refractory Status Epilepticus in a Neurological Intensive Care Unit. Neurocrit Care 31(1): 24-29.

- Rohracher A, Kalss G, Neuray C, Höfler J, Dobesberger J, et al. (2018) Perampanel in patients with refractory and super-refractory status epilepticus in a neurological intensive care unit: A single-center audit of 30 patients. Epilepsia 59 Suppl 2: 234-242.

- Di Bonaventura C, Labate A, Maschio M, Meletti S, Russo E (2017) AMPA receptors and perampanel behind selected epilepsies: current evidence and future perspectives. Expert Opin Pharmacother 18(16): 1751-1764.