Multimodality Imaging Findings and Surgical Treatment of a Patient with Symptomatic, Bilateral, Gigantic Extracranial Carotid Artery Aneurysms Case Report and Review of the Literature

Chrysostomos Xerras1, Marianthi Arnaoutoglou1*, Vasileios Rafailidis2, Konstantinos Kapoulas3, Konstantinos Notas1, Thomas Tegos1, Konstantinos Kouskouras2 and Kyriakos Ktenidis3

1Department of Neurology, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece

2Department of Radiology, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece

3Department of Medical Propaedeutic Surgery, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece

Submission: January 18, 2019; Published: March 12, 2019

*Corresponding author: Marianthi Arnaoutoglou, Department of Neurology, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, AHEPA University General Hospital, St. Kiriakidis 1, P.O. 54636, Thessaloniki/Greece

How to cite this article: Chrysostomos X, Marianthi A, Vasileios R, Konstantinos K, Konstantinos N, et al. Multimodality Imaging Findings and Surgical Treatment of a Patient with Symptomatic, Bilateral, Gigantic Extracranial Carotid Artery Aneurysms Case Report and Review of the Literature . Open Access J Neurol Neurosurg. 2019; 9(5): 555774. DOI: 10.19080/OAJNN.2019.09.555774.

Abstract

We are reporting the case of a 59-years-old male with symptomatic, bilateral, gigantic extracranial carotid artery aneurysms, treated with excision and synthetic graft interposition. The multimodality imaging findings (on ultrasound, Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound (CEUS), Multidetector Computed Tomography Angiography (MDCTA) and contrast-enhanced Magnetic Resonance Angiography (MRA) are also included. Aneurysms of the common carotid artery are rather rare, with an unclear etiology, while the bilateral presentation increases additionally the sparseness of the finding. We review the recent literature concerning the epidemiology, the clinical management and the treatment options of the abovementioned condition.

Keywords: Carotid artery aneurysm; Bilateral; Stroke; CEUS; Endovascular

Abbrevations: CEUS: Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound; MDCTA: Multidetector Computed Tomography Angiography; MRA: Magnetic Resonance Angiography; ECAA: Extracranial Carotid Arteries Aneurysm

Introduction

Extracranial Carotid Arteries Aneurysms (ECAAs) are defined as a permanent, localized increase of the diameter of the artery more that 50% of the reference values. Concerning the internal carotid artery, the reference values are 0.55±0.06 cm for men and 0.49±0.07 cm for women, while concerning the carotid bulb, the reference values are 0.99±0.10 cm for men and 0.92±0.10m for women [1,2]. As shown in the largest single-center series published so far (by the Texas Heart Institute), expanding over a 36-year period, ECCAs represent <1% of all aneurysms that are surgically treated. Of the 65 recorded patients in this series, only 2 presented bilateral aneurysms (4 of 67 aneurysms treated). Therefore, bilateral ECCAs constitute an extremely rare presentation of an already rare condition (6-12% of all carotid aneurysms) [3].

Case report

A 59-years- old male developed an acute symptomatology corresponding to a left hemispheric stroke. The neurological examination documented dysarthria, paresis of the lower part of the right facial nerve (VII cranial nerve), right hemihypesthesia, right hemiparesis (2/5 on upper and 1/5 of lower limp of the MRC Scale) and right Babinski sign. His medical history included smoking for more than 30 years (2ppd), mild consumption of alcohol and hypertension (treated with nebivolol and indapamide). There was no history of connective tissue disease, trauma of previous surgical operation in the neck.

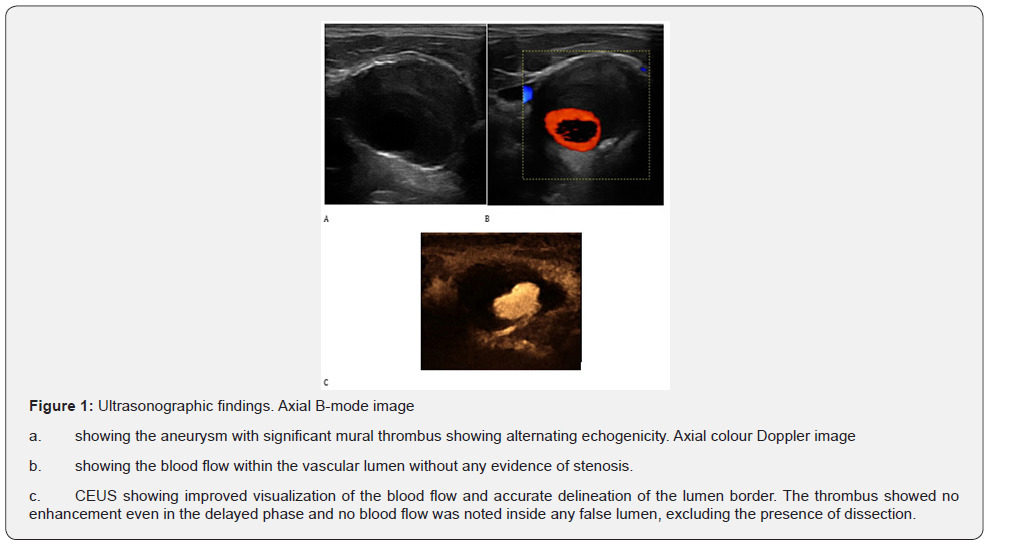

The 24-hour Holter ECG Monitoring and the transthoracic echocardiogram followed by a saline contrast study (bubble study- for the exclusion of patent Foramen Ovale (PFO) were normal. The investigation of the coagulating and the immune system revealed no major anomaly. The patient initially underwent ultrasound of the carotid arteries. Note was made of large aneurysms affecting both carotid bifurcations and containing significant mural thrombus appearing with alternating echogenicity on B-mode technique. Color Doppler technique showed blood flow signals within the vascular lumen, without any evidence of stenosis or occlusion. However, due to the Doppler angle dependence and aliasing or overwriting artifacts, it was not possible to accurately delineate the exact luminal borders and exclude the presence of slow flow within a potential false lumen (Figure 1).

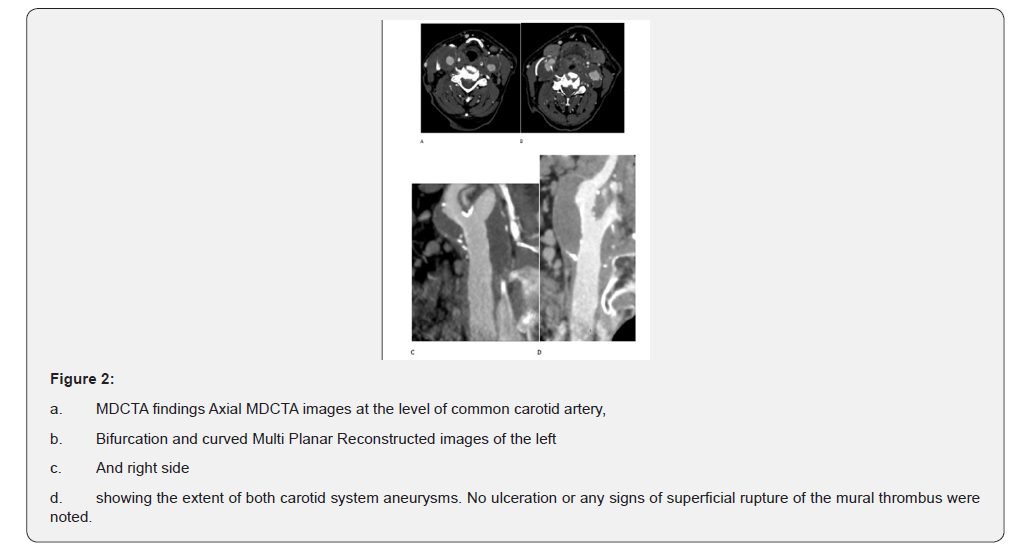

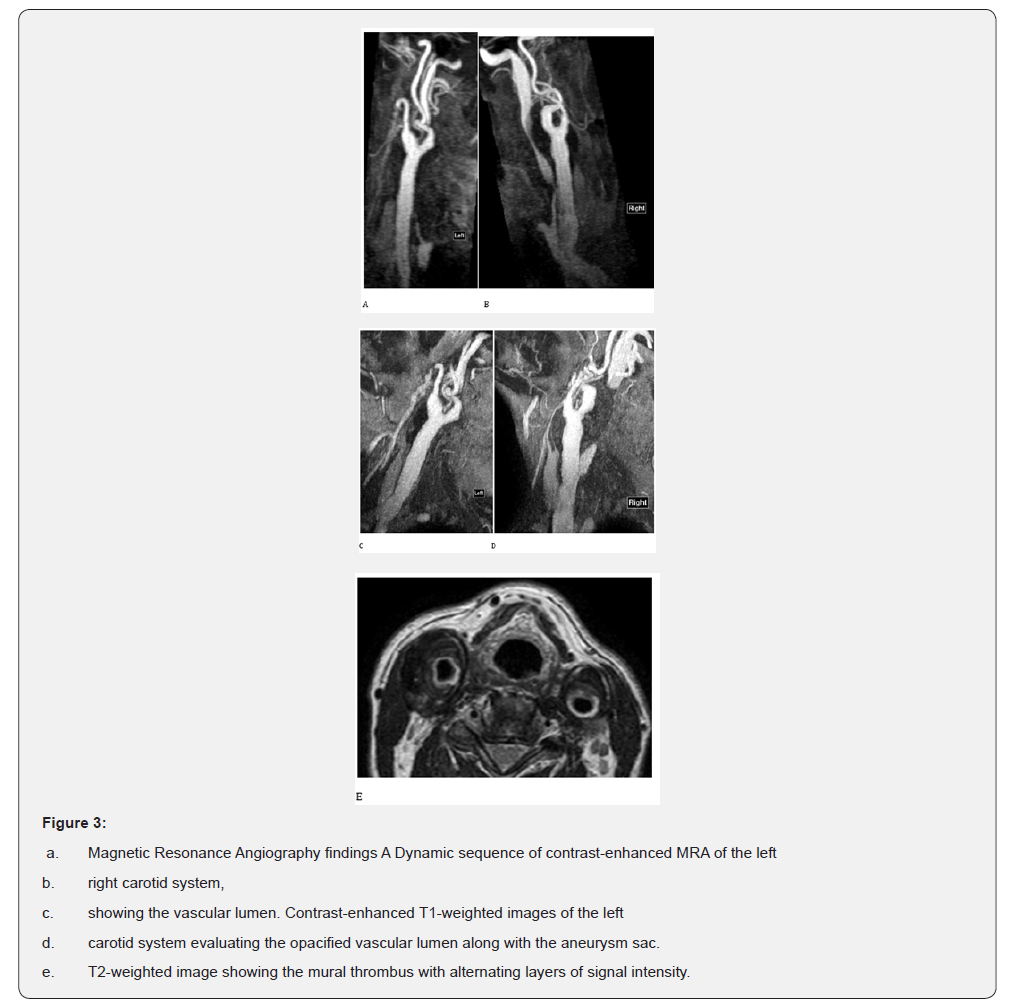

Following the intravenous administration of 2.4 ml of SonoVue, Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound (CEUS) improved visualization of blood flow and detailed delineation of vascular lumen, confidently excluding the presence of slow flow within a hidden false lumen. The suspected diagnosis of dissection was thus excluded and the diagnosis of simple aneurysms with mural thrombus was suggested (Figure1). Multi Detector Computed Tomography Angiography (MDCTA) of the carotid arteries confirmed the presence of bilateral aneurysms with significant mural thrombus affecting carotid bifurcations and excluded the presence of any abnormalities in the intracranial circulation (Figure 2). The patient also underwent contrast-enhanced Magnetic Resonance Angiography (MRA) of the carotid arteries. The carotid’s lumen was evaluated on the contrast-enhanced angiography sequence while the mural thrombus appeared with heterogeneous low signal intensity on T2-weighted images (Figure 3). Similarly, to B-mode US, the thrombus showed an alternating pattern with layers of slightly higher signal intensity and areas of lower signal intensity. This pattern was accurately demonstrated on MRI and B-mode US with adequate contrast but was less well appreciated on MDCTA, where it appeared homogeneously hypodense. Nevertheless, MDCTA could delineate with better spatial resolution the exact borders of the vascular lumen.

Results

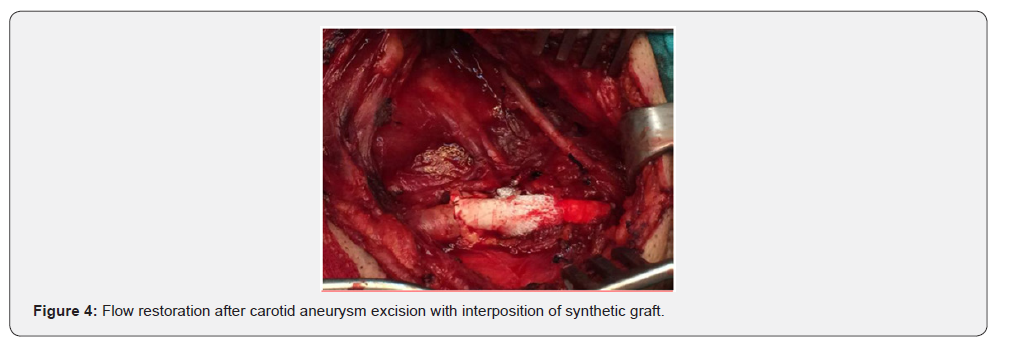

The clinical symptomatology of the patient showed gradual improvement (4/5 overall of the MRC Scale) and a surgical intervention was decided, starting from the symptomatic (left) side. Under general anesthesia, the patient was uneventfully subjected to aneurysm resection and restoration with synthetic graft interposition (PTFE, polytetrafluoroethylene), (Figure 4). After 2 weeks, a similar intervention was effectuated in the other side, again without any complications.

Discussion

ECAAs constitute a rather rare condition. A classic retrospective review of the literature by Schechter from 1687 to 1977 reported only 853 cases, of which the 33 where bilateral aneurysms (3.87%) [4]. Various case series of different major centers confirm the above findings Zwolak, et al. [5]. 24 atherosclerotic aneurysms- 3 of them bilateral (12.5%) in a 25-years period, Moreau, et al. [6]. 38 aneurysms -3 of them bilateral (7.8%)- in a 24-year period, Szopinski, et al. [7]. 15 aneurysms -none bilateral- in a 20-years period, Rosset, et al. [8]. 25 aneurysms among 1936 carotid reconstructions -none bilateral- in a 18-years period, and more recently, Jan Paweł Skora, et al. [9]. 32 aneurysms- 1 of them bilateral (6,25%) in a 26-years period). As mentioned before, the largest, to date, single center study reported a 6% chance of bilateral presentation [2]. ECCAs are twice as common in male patients, while the mean age of presentation is 56 years [10].

Central neurological deficit constitutes a main clinical manifestation of ECAAs, either as a transient ischemic attack (up to 60% of patients, with a 33% of them presenting amaurosis and 21% presenting hemispheric symptoms) or even as a stroke (8% of patients) [3]. The pathogenic mechanism is usually embolism by thrombotic material of the aneurismal wall. Reduction of the flow of the internal carotid artery due to compression of the internal carotid artery by the aneurysm at certain positions of the head is also suggested [10]. Other manifestations may include: tender (up to 33%) or pulsative (up to 80%) cervical masses, dysphagia, hemicrania, Horner’s syndrome (due to compression of the cervical sympathetic chain), cranial nerve paresis due to compression, otolaryngologic signs (tinnitus, vertigo, epistaxis, hoarseness), while rupture and hemorrhage are rather rare complications [3,11].

The differential diagnosis of ECAA consists mainly of the differential diagnosis of a neck mass and includes prominent carotid bifurcation, cervical lymphadenopathy, carotid body tumors, glomus jugulare tumors, cervical metastatic disease, branchial cleft cysts, cystic hygromas and torturous carotid or subclavian arteries [11,12]. ECCAs are mainly classified in the literature as true aneurysms and pseudoaneurysms, according to their different etiologies [3,12]. True ECCAs may account for up to 70% of all ECCAs and are linked to a degenerative process, primarily atherosclerosis (which has lately been considered a secondary event rather than a primary etiologic factor) and secondarily fibromuscular dysplasia, neck irridation, neurofibromatosis, Marfan’s syndrome and Takayasu’s arteritis [3,12,13]. The older, dominant infectious causality by staphylococcus aureus and streptococcus pyogenous has greatly declined after the introduction of antibiotic, with only 31 cases been reported since [14]. Pseudoaneurysms include post-traumatic aneurysms and post-Carotid Endarterectomy (CEA) aneurysms, which are a rather rare complication of CEA (less than 0,5% of all CEA [15]. A first point of interest is the increase of post-CEA aneurysms in recent studies (21% of ECCAs in the 1990 study by McCann [10] vs 57% in the 2000 THI study [2]), possibly due to the increased time of observation (as the development of a pseudoaneurysm may take as long as 15 years [2]) and possibly, as well, due to the increased popularity of the procedure.

After the 1991 nadir with about 67,000 procedures effectuated in the United Stated, the total number rose to 108,275 in 1996 [16] and has reached a plateau during the last years at about 100,000 procedures per year (2006: 99,000, 2007: 91,000, 2008: 120,000, 2009: 93,000, 2010: 100,0000), as showed by the projections from the National Hospital Discharge Survey (NHDS),sponsored annually by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) (ICD-9-CM code 38.12) [17-21]. A second point of interest is the increased frequency of dysplastic ECCAs in recent times, possibly due to the increased vigilance and surveillance after spontaneous carotid artery dissections [8].

The reasoning necessitating surgical treatment is wellestablished (12- page 1589) and focused in the prevention of permanent neurological deficits secondary to thromboembolism. As showed in the 1926’s report by Winslow, untreated ECCAs are linked to a mortality rate of 71% (in contrast to a mortality rate of 28% when treated), while the more recent study by Zwolak, et al. [5] reported a stroke rate as high as 50% of atherosclerotic ECCAs that were treated nonoperatively [5,11,22].

The recommended surgical treatment of choice has evolved greatly with the passage of time. Historically, the first successful intervention (Sir Astley Copper, 1808) consisted of carotid ligation, a trend that lasted until the 1950s, despite an alarming mortality/major stroke rate of 20% to 60%. Since the 1970s, resection of the aneurysm and reconstruction of the carotid axis has been firmly established as the treatment of choice [14]. Different surgical techniques may be utilized, depending on the anatomical specifics. A direct end-to-end anastomosis of the internal carotid artery either to the proximal internal carotid artery or to the common carotid artery can be applied. An interposition graft (either a homologous saphenous vein graft or a Dacron or polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) graft) can be used when the vessels’ length is inefficient. The external carotid artery is commonly ligated but may be implanted into the vein graft [3,11, 12]. During the last years, endovascular techniques are increasingly applied (although some concerns about their long-term effectiveness have been raised [11]), especially after a report by Zhou et al reported shorter convalescent and less procedural-related complications [21].

The endovascular techniques mainly aim to the elimination of the arterial inflow to the aneurysm lumen, preserving the patency of the vessel, via the placement of a stent at the aneurysm’s neck. According to the reviewed literature, more than 50 patients with true ECCAs have already being treated successfully with endovascular stenting. The corresponding postoperative stroke and death rates are at least equivalent with the ones corresponding to the open procedure, while the possibility of cranial nerve damage is eliminated [3,23,24]. At the selection of treatment, besides coexisting comorbidities, the location and the size of the carotid are of critical importance. A larger size and a distal ICA localization lean towards an endovascular treatment, whereas the presence of thrombotic material lean towards an open treatment. In our case, the proximal ICA localization, the lack of a narrow aneurysm’s neck and the clear presence of significant mural thrombus, as revealed by the multimodality imaging findings, guided us towards an open approach (14-page 1592).

Contrast-enhanced ultrasound has been recently introduced in the field of carotid imaging providing promising results in certain applications including many aspects of carotid atherosclerotic disease. It is performed with the intravenous administration of an ultrasonographic contrast agent consisting of microbubbles which is characterized by excellent safety profile and importantly is not nephrotoxic. The primary advantage of this technique is its potential to readily and significantly improve blood flow visualization, offering increased detail even in vascular segments with slow flow like highly stenotic vessels, false lumens in dissected vessels, carotid ulcerations and intraplaque neovessels. In the case of extracranial carotid arteries aneurysms, the use of microbubbles help confidently image blood flow and visualize mural thrombus while excluding the possibility of a hidden false lumen. CEUS may be considered superior to MDCTA in this respect as it offers the possibility to dynamically scan the opacified lumen for more than 4 minutes and thus detect false lumen opacification even in the delayed phase. Given the use of ionizing radiation, this is not feasible with MDCTA which routinely includes up to three scans. Nevertheless, virtually every modality including US, CEUS, MDCTA and MRA can be used in order to evaluate carotid lumen and identify mural changes like aneurysms, ulcerations or mural thrombus, each with a different degree of spatial resolution and diagnostic accuracy [25-29].

References

- Johnston KW, Rutherford RB, Tilson MD, Shah DM, Hollier L, et al. (1991) Suggested standards for reporting on arterial aneurysms. Subcommittee on Reporting Standards for Arterial Aneurysms, Ad Hoc Committee on Reporting Standards, Society for Vascular Surgery and North American Chapter, International Society for Cardiovascular Surgery. J Vasc Surg 13(3): 452-458.

- El-Sabrout R, Cooley DA (2000) Extracranial carotid artery aneurysms: Texas Heart Institute experience. J Vasc Surg 31(4): 702-712.

- James C Stanley, Frank J Veith, Thomas W, Wakefield In: current therapy in vascular and endovascular surgery. 5th (edn), Elsevier, Netherlands, UK.

- Schechter DC (1979) Cervical carotid aneurysms. NY State J Med 79(6): 892-901.

- Zwolak RM, Whitehouse WM, Knake JE, Bernfeld BD, Zelenock GB, et al. (1984) Atherosclerotic extracranial carotid artery aneurysms. J Vasc Surg 1(3): 415-422.

- Moreau P, Albat B, Thévenet A (1994) Surgical treatment of extracranial internal carotid artery aneurysm. Ann Vasc Surg 8(5): 409-416.

- Szopinski P, Ciostek P, Kielar M, Myrcha P, Pleban E, et al. (2005) A series of 15 patients with extracranial carotid artery aneurysms: surgical and endovascular treatment. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 29(3): 256-261.

- Rosset E, Albertini JN, Magnan PE, Ede B, Thomassin JM (2000) Surgical treatment of extracranial internal carotid artery aneurysms. J Vasc Surg 31(4): 713-723.

- Jan Paweł Skóra, Jacek Kurcz, Krzysztof Korta, Przemysław Szyber, Tadeusz Andrzej Dorobisz, et al. (2016) Surgical management of extracranial carotid artery aneurysms. Vasa 45(3): 223 -228.

- Mc Cann RL (1990) Basic data related to peripheral artery aneurysms. Ann Vasc Surg 4(4): 411-414.

- Anwar SC, Richard JE, Dilip KN, Ramesh KT, Janaka KW (2009) Surgical management of extracranial carotid artery aneurysms. ANZ Journal of Surgery 79(4): 281-287.

- Jack LC, Wayne JK In: Rutherford’s Vascular Surgery, 8th (Edn) Elsevier, Netherlands, UK.

- Tabata M, Kitagawa T, Saito T, Uozaki H, Oshiro H, et al. (2001) Extracranial carotid aneurysm in Takayasu’s arteritis. J Vasc Surg 34(4): 739-742.

- Biasi L, Azzarone M, De Troia A, Salcuni P, Tecchio T (2008) Extracranial Internal Carotid Artery Aneurysms: case report of a saccular widenecked aneurysm and review of the literature. Acta Biomed 79(3): 217-222.

- Abdelhamid MF, Wall ML, Vohra RK (2009) Carotid artery pseudoaneurysm after carotid endarterectomy: case series and a review of the literature. Vasc Endovascular Surg 43(6): 571-577.

- Hsia DC, Moscoe LM, Krushat WM (1998) Epidemiology of Carotid Endarterectomy Among Medicare Beneficiaries 1985–1996 Update. Stroke 29(2): 346-350.

- https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhds/nhds06all-listedprocedures. pdf

- https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhds/10detaileddiagnosesprocedures/ 2007det10_alllistedprocedures.pdf

- https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhds/10detaileddiagnosesprocedures/ 2008det10_numberalldiagnoses.pdf

- https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhds/10detaileddiagnosesprocedures/ 2009det10_alllisteddiagnoses.pdf

- https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhds/10detaileddiagnosesprocedures/ 2010det10_numberalldiagnoses.pdf

- Zhou W, Lin PH, Bush RL, Peden E, Guerrero MA, et al. (2006) Carotid artery aneurysm: Evolution of management over two decades. J Vasc Surg 43(3): 493-496.

- Li Z, Chang G, Yao C, Guo L, Liu Y, et al. (2011) Endovascular stenting of extracranial carotid artery aneurysm: a systematic review. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 42(4): 419-426.

- Han DK, Tadros RO, Chung C, Patel A, Marin ML, et al. (2016) Endovascular Treatment of 2 Synchronous Extracranial Carotid Artery Aneurysms Using Stent-Assisted Coil Embolization and Double Bare-Metal Stenting. Vasc Endovascular Surg 50(2): 102-106.

- Clevert DA, Graser A, Jung EM, Stickel M, Reiser M (2008) Value of ultrasound in the diagnosis of aneurysms of the extracranial internal carotid arteries. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc 39(1-4): 133-146.

- Rafailidis V, Pitoulias G, Kouskouras K, Rafailidis D (2015) Contrast-enhanced ultrasonography of the carotids. Ultrasonography 34(4): 312- 323.

- Rafailidis V, Charitanti A, Tegos T, Destanis E, Chryssogonidis I (2016) Contrast-enhanced ultrasound of the carotid system: a review of the current literature. J Ultrasound 20(2): 97-109.

- Rafailidis V, Chryssogonidis I, Tegos T, Kouskouras K, Charitanti-Kouridou A (2017) Imaging of the ulcerated carotid atherosclerotic plaque: a review of the literature. Insights Imaging 8(2): 213-225.

- Rafailidis V, Charitanti A, Tegos T, Rafailidis D, Chryssogonidis I (2016) Swirling of microbubbles: Demonstration of a new finding of carotid plaque ulceration on contrast-enhanced ultrasound explaining the arterio- arterial embolism mechanism. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc 64(2): 245-250.