Assessment of Some Haematological and Biochemical Parameters of Family Replacement Blood Donors in Gusau, Nigeria

Imoru Momodu1*, Sani Abdulkadir2, Isah Suleiman Yahaya3 and Erhabor Osaro1

1 Haematology Department, Usmanu Danfodiyo University, Nigeria

2 Hospital Service Management Board, Nigeria

3Department of Medical Laboratory Science, Bayero Uniiversity, Nigeria

Submission: August 03, 2018; Published: August 31, 2018

*Corresponding author: Imoru Momodu, Haematology Department, School of Medical Laboratory Science, Usmanu Danfodiyo University, Sokoto, Nigeria.

How to cite this article: Imoru M, Sani A, Isah S Y, Erhabor O. Assessment of Some Haematological and Biochemical Parameters of Family Replacement Blood Donors in Gusau, Nigeria. Open Acc Blood Res Trans J. 2018; 2(4): 555593. DOI: 10.19080/OABTJ.2018.02.555593

Abstract

Background: Millions of lives are saved each year through blood transfusions and these necessitate the regular supply of blood to treat patients requiring transfusions. The aim of this study was to determine the haematological and biochemical parameters of family replacement donors since they are the major source of blood donors in Northern Nigeria.

Materials and methods:Two-hundred and twenty-eight family replacement donors, whose ages were 18-54 years, were recruited from Federal Medical Centre and Yariman Bakura Specialist Hospital, Gusau, Zamfara State for the determination of values of haematocrit, haemoglobin, RBC count, MCH, MCV, MCHC, serum iron, serum ferritin and TIBC using standard techniques.

Results: The values of haematocrit, haemoglobin, RBC count, MCH, MCV and MCHC were 38.8±3.6%, 12.6±1.3g/dL, 5.3±0.56 X 1012/L, 23.9±2.0pg, 73.6±6.2 fl, 32.6±2.5g/dL, respectively while the levels of serum iron, serum ferritin and TIBC were 15.3±5.2μmol/L, 69.4±45.1ng/ml, 45.5±15.4μmol/L, respectively. Age groups of ˂ 24 years, 25-34 years, 35-44 years and 45-54 years had no significant effects on the values of haematocrit, haemoglobin, RBC count, MCH, MCV, MCHC, serum iron, serum ferritin and TIBC (P˃0.05).

Conclusion: Family replacement donors should be encouraged for donation since they have similar values of haematological and biochemical parameters compared to voluntary and first-time donors. In the process, there will be sufficient units of blood in the blood banks as a result of the increased number of unused blood donated by these donors.

Keywords: Blood donors; Gusau blood transfusions; Blood banks; EDTA; Plan tube; Serum iron; Haemotocrit; Ferritin; Haematological; Biochemical parameters

Abbrevations: MCV: Mean Cell Volume; MCHC: Mean Cell Haemoglobin Concentration; RBC: Red Blood Count; MCH: Mean Cell Haemoglobin; ANOVA: Analysis of Variance; TIBC: Total Iron Blinding Capacity

Introduction

Millions of lives are saved each year through blood transfusions and these necessitate the regular supply of blood to treat severe anemia in children under five years old, management of pregnancy related complications, massive trauma, cancer among other conditions [1,2].

A blood donor generally donates approximately 450ml of blood, which results in a loss of approximately 225mg of iron with subsequent mobilization of iron from body iron stores. However, if the donor has no iron-deficiency, the erythrocytes and the haemoglobin level will generally return to normal within 3-4 weeks. Therefore, adequate iron stores are very important in the maintenance of the donor [2-4]. The regulation of systemic iron is through the problems “transferrin” (iron mobilization) and “ferritin” (iron sequestration) [5] but the indicator of mobilizable body iron stores is the serum ferritin concentration [6].

The American Association of Blood Banks has standard minimum haemoglobin levels of 13.5g/dL and 12.5g/dL for men and women blood donors, respectively [4]. In Nigeria, there seems to be less emphasis on the haematological and biochemical parameters of family replacement donors that are predominantly source of blood donors in Northern Nigeria. Therefore, the objective of this study was to determine the values of some haematological and biochemical parameters of family replacement donors in order to guide the blood bank staff in the selection of blood donors in Zamfara, Northern Nigeria.

Materials and Methods

A total of two hundred and twenty-eight (228) recruited family replacement donors from Federal Medical Centre and Yariman Bakura Specialist Hospital, Gusau, Zamfara State, whose ages were 18-65 years were studied between January and December, 2015.

The inclusion criteria for the blood donors were that they must be sero-negative for Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV 1 and 2), hepatitus B and C viruses and syphilis infections while the exclusion criteria were based on current iron therapy and recent blood donation, that is, less than three months.

After the written consent from the blood donors and ethical clearance letter from the ethical committees of Federal medical Centre and Yariman Bakura Specialist Hospital, Gusau, Zamfara State, five milliliters (5ml) of whole blood was collected from each blood donor asceptically and 2ml of blood was put into tripotassium EDTA tube while the remaining 3ml was put in a plan tube.

The blood samples in the EDTA bottles were analyzed for full count using Mythic 18, automated haematology analyzer while the samples in the plain containers were analyzed for serum iron level using iron NP colorimetric test kit with Nitro-PAPS, serum ferritin level using Human Ferritin Elisa Kit and total iron blinding capacity (TIBC) level using Chemelex Labkit. All these kits were used based on the manufacturers’ instructions.

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 20 and the results were expressed as mean±standard deviation while comparison of haematological and biochemical parameters of family replacement blood donors with age was analyzed using analysis of variance (ANOVA). P˂ 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

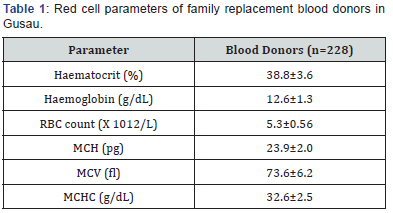

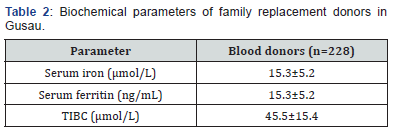

The red cell parameter of family replacement blood donors in Gusau are shown in Table 1. The mean values for haematocrit, haemoglobin, red blood count (RBC) count, mean cell haemoglobin (MCH), mean cell volume (MCV) and Mean cell haemoglobin concentration (MCHC) were 38.8 ± 3.6%, 12.56 ± 1.3g/dL, 5.3 ± 0.56 X 1012 /L, 23.9 ± 2.0 pg, 73.6 ± 6.2fl and 32.6 ± 2.5g/dL, respectively. Table 2 shows the biochemical parameters of family replacement blood donors in Gusau. The mean values for serum iron, serum ferritin and TIBC were 15.3 ± 5.2μmol/L, 69.4 ± 45.1ng/mL and 45.5 ± 15.4μmol/L.

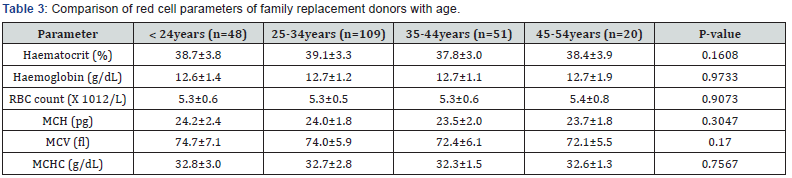

Comparison of red cell parameters of family replacement blood donors with age is show in Table 3. The age groups of ˂24 years, 25-34 years, 35-44 years and 45-54 years had haematocrit levels of 38.4 ± 3.9%, 39.1 ± 3.3%, 37.8 ± 3.0% and 38.4 ± 3.9%, respectively (P = 0.1608); haemoglobin values of 12.6 ±1.4g/dL, 12.7 ± 1.2 g/dL, 12.7 ± 1.1 g/dL and 12.7 ± 1.9 g/dL, respectively (P = 0.9733); RBC counts of 5.3 ± 0.6 X1012/L, 5.3 ± 0.5 X 1012/L, 5.3 ± 0.6 X 1012/L and 5.4 ± 0.8 x 1012/L, respectively (P = 0.9073); MCH values of 24.2 ± 2.4 pg, 24.0 ± 1.8pg, 23.5 ± 2.0pg and 23.7 ± 1.8pg, respectively (P= 0.3047); MCV values of 74.7 ± 7.1 fl, 74.0 ± 5.9 fl, 72.4 ± 6.1 fl and 72.1 ± 5.5 fl, respectively (P = 0.17), and MCHC values of 32.6 ± 3.0g/dL, 32.7 ± 2.8g/dL, 32.3 ± 1.5g/dL and 32.6 ± 1.3g/dL, respectively (P = 0.7567).

Table 4 reveals the comparison biochemical parameters of family replacement blood donors with respect to age. The age group of ˂24 years, 25-34 years, 35-44 years and 45-54 years had serum iron levels of 14.6 ± 4.2μmol/L, 15.7 ± 5.6μmol/L, 14.8 ± 5.8μmol/L and 15.7 ± 2.9μmol/L, respectively (P= 0.5539); serum ferritin levels of 58.5 ± 27.5ng/m, 68.3 ± 42.9ng/ mL, 74.4 ± 49.3ng/mL and 89.6 ± 70.2ng/mL, respectively (P= 0.0576); TIBC values of 43.9 ± 12.4μmol/L, 46.5 ± 16.5μmol/L 44.6 ± 17.4μmol/L, 46.7 ± 8.9μmol/L, respectively (P = 0.737).

Discussion

The importance of haematological and biochemical parameters of family replacement donors in Nigeria cannot be overemphasized since they are predominantly the source of blood donors in northern Nigerian and Nigeria as a whole.

The values of haemocrit, haemoglobin and RBC count of family replacement donors in this study are consistent with the findings of previous researchers on apparently healthy donors, first-time donors, voluntary donors and samples from prospective blood donors at Kenyan regional blood transfusion centres [2,7-10]. This shows that the values of haemotocrit, haemoglobin and RBC count are comparable to that of voluntary donors and therefore, family replacement donors should be encouraged for blood donation in Northern Nigeria provided the donors are free from transfusion transmissible infections in addition to satisfying all other requirements for blood donation. This will further boost the units of blood in our blood banks in Nigeria since some of the units of blood donated for the patients by the relatives are not utilized.

In this study, there were no statistically significant differences in the values of haemotocrit, haemoglobin and RBC count of family replacement blood donors with respect to age and these are in line with the earlier report [11].

The study has further revealed the lower values of 23.9 ± 2.0pg and 73.6 ± 6.2 fl for MCH and MCV, respectively compared to the previous studies on voluntary donors, first time donors and apparently healthy donors. The differences might be associated with mild lower values of haemoglobin and haematocrit in this study [2,9,12]. However, the value of MCHC observed in this study is in line with the earlier findings [2,9,12]. The values of MCHC, MCV and MCHC among the family replacement donors did not differ with age and these are in support of previous study on healthy Chinese adults [13].

Divergent views have been expressed on the serum iron and ferritin levels of blood donors. This study has revealed serum iron and ferritin levels of 15.3 ± 5.2μmol/L and 69.4 ± 45.1ng/ mL, which are in agreement with some of the previous findings on first-time donors [2,14-16] but at variance with the reports from other studies. The different values from various authors could be associated with the dietary habits of blood donors, sensitivities of serum iron and ferritin kits utilized, and techniques among other factors [8,10]. However, the serum iron and ferritin levels are within the reference ranges [17].

Total iron binding capacity (TIBC) level in this study is lower than the reported TIBC values on first-time blood donors. However, the reported values from all authors are within the documented wide reference range [18] but the different values for TIBC may be associated with the techniques employed and sensitivity of kits [2,8,14]. The mean values of serum iron, ferritin and TIBC did not differ significantly with respect to age in this study.

Conclusion

In conclusion, since there are no adequate voluntary donors to donate sufficient blood for most of our patients in Nigeria, family replacement donors, that are usually non-remunerated donors should be encouraged for donation based on comparable or similar haematological and biochemical parameters to the voluntary and first-time donors. In the process, units of blood in our blood banks will be boosted as a result of unused pints of blood donated by the relatives of these patients and the deaths associated with massive blood loss will be reduced significantly.

References

- Hoque MM, Adnan SD, Begum HA, Rahman M, Rahman SM, et al. (2012) Haemoglobin level among the regular voluntary blood donors. J Dhaka Med Coll 20(2): 168-173.

- Thomas V, Mithrason AT, Silambanan S (2016) A Study to assess the iron status of regular blood donors. Int J Clin Biochem Res 3(4): 466- 468.

- Ranney HM, Rapaport SI (1991) The red blood cell. In: Best and Taylor’s Physiological Basis of Medical Practice. 12th edn. Williams and Wilkins, Baltimore, pp. 369-384.

- Huestis DW, Busch S (1976) Selection of blood donors. In: Practical blood transfusion. 2nd edition. Little Brown and Company, Boston, USA, pp. 7-48.

- Roskams AJ, Connors JR (1994) Iron, transferrin and ferritin in the rat brain during development and aging. J Neurochem 63(2): 709-716.

- Milman N (1996) Serum Ferritin in Danes: Studies of iron status from infancy to old age, during blood donation and pregnancy. Int J Hematol 63(2): 103-135.

- Rajab JA, Muchina WP, Orinda DAO, Scott CS (2005) Blood donor haematology parameters in two regions of Kenya. East Afr Med Journal 82(3): 124-128.

- Moghadam AM, Natanzi MM, Djalali M, Saedisomeolia A, Jaranbankht MH, et al. (2013) Relationship between blood donors iron status and their age, body mass index and donation frequency. Sao Paolo Med Journal 131(6): 377-383.

- Nubila T, Ukaejiofo EO, Nubila NI, Shu EN, Okwuosa CN, et al. (2014) Hematological profile of apparently healthy blood donors at a tertiary hospital in Enugu, Southwest Nigeria: A pilot study. Niger J Exp Clin Biosci 2(1): 33-36.

- Tailor HJ, Patel PR, Pandya AN, Mangukiya S (2017) Study of various haematological parameters and iron status among voluntary blood donors. Int J Med Public Health 7(1): 61-65.

- Okpokam DC, Okafor IM, Akpotuzor JO, Nna Vu, Okpokam OE, et al. (2016) Response of cellular elements to frequent blood donations among male subjects in Calabar Nigeria. Trends Med Res 11:11-19.

- Nwogoh B, Awodu OA, Bazuaye GN (2012) Blood donation in Nigeria: Standard of the donation blood. J Lab Physicians 4(2): 94-97

- Wu X, Zhao M, Pan B, Zhang J, Peng M, et al. Complete blood count reference intervals for healthy Han Chinese adults. PloS ONE 10(3): e0119669.

- Okpokam DC, Emeibe AO, Akpotuzor JO (2012) Frequency of blood donation and iron stores of blood donors in Calabar, Cross-River, Nigeria. Int J Biomed Lab Sci (IJBLS) 1(2): 40-43.

- Subinary D, Mrinal P, Chinmoy G (2013) Effect of frequent blood donation on iron status of blood donors in Burdwan West Bengal, India. J Drug Del Therapeutics 3(6): 66-69.

- Badar A, Ahmed A, Ayub M, Ansari AK (2002) Effect of frequent blood donations on iron stores of non-anaemic male blood donors. J Ayub med Coll Abottabad 14(2): 24-27.

- Mahida VI, Bhatti A, Gupte SC (2008) Iron status of regular voluntary blood donors. Asian J Tranfus Sci 2: 9-12.

- Fauci AS, Braunwald E (2008) Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. In: Fauci AS, et al. (eds.), (17th edn.), McGraw Hill Companies: New York, pp. 2432.