Osteoarticular Maneuvers for Pain Relief and Restoration of Ankle Mobility

Guilherme de Souza Farias1, Dérrick Patrick Artioli2, Marcus Vinicius Gonçalves Torres Azevedo2 and Gladson Ricardo Flor Bertolini3*

1Undergraduate Student in Physiotherapy, Centro Universitário Lusíada, Brazil

2Master in Internal Medicine, Lusíada University Center, Brazil

3PhD in Health Sciences applied to the Locomotor Apparatus, University of São, Brazil

Submission: May 4, 2022; Published: May 26, 2022

*Corresponding author: Gladson Ricardo Flor Bertolini, PhD in Health Sciences applied to the Locomotor Apparatus, University of São, Brazil

How to cite this article: Guilherme d S F, Dérrick P A, Marcus V G T A, Gladson R F B. Osteoarticular Maneuvers for Pain Relief and Restoration of Ankle Mobility. J Yoga & Physio. 2022; 10(1): 555776. DOI:10.19080/JYP.2021.10.555776

Keywords: Pain relief; Physiotherapy; Ankle mobility; Ankle injury; Musculoskeletal injury; Rehabilitation; Exercise; Physiotherapist; Orthopaedic

Abbreviations: AAOMPT: American Academy of Orthopaedic Manual Physical Therapists; IFOMPT: International Federation of Orthopaedic Manipulative Physical Therapists; OMPT: Orthopaedic Manual Physical Therapy; FLAQ: Federación Latino Americana de Quiropráctica; MWM: Mobilization with Movement

Generalized Anxiety Disorder

Among the musculoskeletal injuries, ankle injury represents about 25% of all sports injuries, and is the second most affected body part, only behind the knee joint [1]. In 80% of the cases, this joint is affected by sprains, mainly by the inversion mechanism of the hindfoot and external rotation of the tibia, compromising the lateral ankle ligament complex, causing pain and alteration of function for weeks [2,3]. It occurs most often in women and about 74% progress to chronic instability. Even after 12 months, about 33% of patients complain of pain, swelling, and stiffness. Symptoms that after 5 years persist in 20% of those affected and are associated with inadequate rehabilitation [4,5]. The ankle supports 1.5 times the body weight during walking and 5.5 times the body weight during intense running [6]. It is the most common load-bearing joint in the human body, with malleolar fractures being the most common, and the patient may be immobilized for 6-12 weeks depending on whether the fracture is stable or unstable. The patient commonly presents a pain and restricted range of motion to be addressed in physical therapy [7,8]. For these cases, joint mobilization techniques, such as the Maitland and Mulligan concepts, can collaborate in pain relief, through the activation of ascending analgesic pathways (peripheral - Theory of the floodgates) and descending (central inhibitory pathway), and joint stiffness, by temporarily increasing the space between the articular surfaces. However, these resources are not resolutive but are part of integrated treatment, so in order not to create dependency or false expectations with the maneuvers, the real purpose of the techniques must be explained to the patient [9-13].

In the 70s-90s professional manual therapy organizations were created such as the American Academy of Orthopaedic Manual Physical Therapists (AAOMPT), International Federation of Orthopaedic Manipulative Physical Therapists (IFOMPT), Orthopaedic Manual Physical Therapy (OMPT) and Federación Latino Americana de Quiropráctica (FLAQ), with structure and criteria for learning osteoarticular maneuvers [9]. Today, Maitland’s and Mulligan’s concepts are part of the physiotherapist’s training that seeks knowledge in manual therapy resources and will be briefly addressed in a general way below.

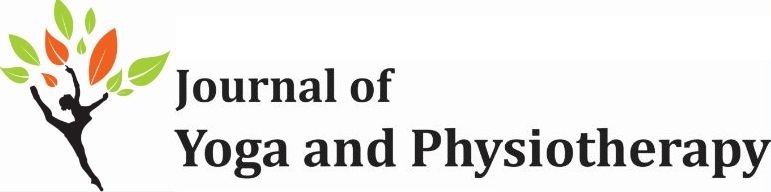

The objective of this scientific communication is to function as a quick reference guide for the physical therapist, based on the illustration and description of the maneuvers applicable to the ankle. Remember that these are basic techniques, with variations and alternatives, but that even so, they should be performed after a previous and specific evaluation of each patient [14]. To facilitate understanding, the techniques were compiled here as “passive, active-assisted, and active”, but usually each concept is studied individually, and these nomenclatures are rarely used. The passive articular techniques (Figure 1) are characterized by oscillatory and rhythmic accessory movements graded I - IV by Maitland or the application of short, rapid force (V - Thrust) on the end-feeling. The patient’s participation is restricted to relaxation, not locking the movement, and allowing the physical therapist to work. Mobilizations I-IV should be applied in 4-6 series of 20 seconds to 2 minutes each, while thrust should be applied only once [15].

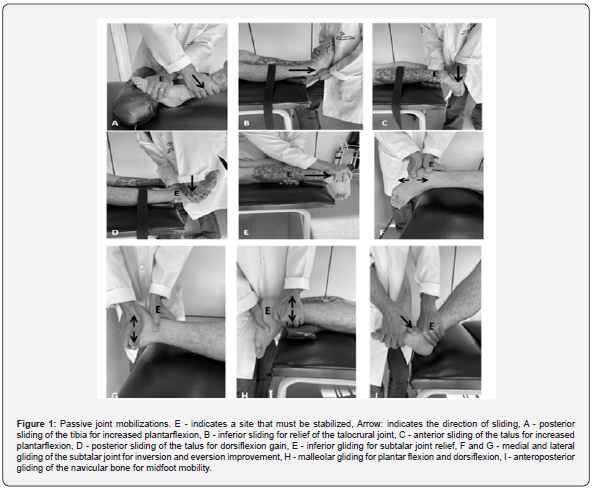

The techniques described here as “active-assisted” (Figure 2) would be based on the knowledge described by Mulligan. During the requested exercise, the physiotherapist should follow the movement with a facilitatory joint sliding (mobilization with movement - MWM) and analyze whether or not there was an improvement of the patient’s complaint. If the answer is positive, the positioning is maintained. If it doesn’t change or worsen the symptoms, then the professional should use another glide until he or she finds a way to help the joint kinematics that provides symptom improvement or decides not to use the technique. This “test” as to the ideal treatment plan (glide) should be done up to a maximum of 10 repetitions and then the MWM performed for 3-4 sets of 10 repetitions. A belt can be used to stabilize or facilitate the movements proposed by Mulligan’s concept [16].

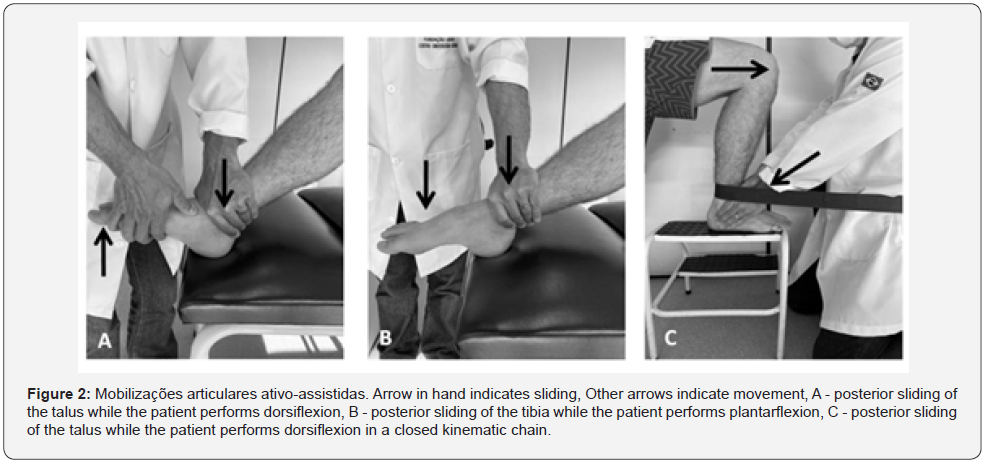

The active joint techniques (Figure 3) are orientations carried out and tested during physiotherapeutic care that should be incorporated into the patient’s routine since symptom improvement has been reported with such movements and the patient can reproduce them accurately. The aforementioned concepts are adopted for active-assisted joint techniques and an overpressure at the end of the movement, to increase the final ROM [12,16].

For these cases, joint mobilization techniques, such as the Maitland and Mulligan concepts, can collaborate in pain relief, through the activation of ascending analgesic pathways (peripheral – Gate control theory) and descending (central inhibitory pathway), and joint stiffness, by temporarily increasing the space between the articular surfaces. However, these resources are not resolutive but are part of integrated treatment, so in order not to create dependency or false expectations with the maneuvers, the real purpose of the techniques must be explained to the patient [9-13].

References

- Powell S (2019) A comparison of two interventions in the treatment of severe ankle sprains and lateral malleolar avulsion fractures. Emerg Nurse 27(5): 23-30.

- Bleakley CM, Taylor JB, Dischiavi SL, Doherty C, Delahunt E (2019) Rehabilitation exercises reduce reinjury post ankle sprain, but the content and parameters of an optimal exercise program have yet to be established: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 100(7): 1367-1375.

- Iammarino K, Marrie J, Selhorst M, Lowes LP (2018) Efficacy of the stretch band ankle traction technique in the treatment of pediatric patients with acute ankle sprains: a randomized control trial. Int J Sports Phys Ther 13(1): 1-11.

- Mailuhu AKE, van Middelkoop M, Bierma-Zeinstra SMA, Bindels PJE, Verhagen EALM (2020) Outcome of a neuromuscular training program on recurrent ankle sprains. Does the initial type of healthcare matter? J Sci Med Sport 23(9): 807-813.

- Delahunt E, Bleakley CM, Bossard DS, Caulfield BM, Docherty CL, et al. (2018) Clinical assessment of acute lateral ankle sprain injuries (ROAST): 2019 consensus statement and recommendations of the International Ankle Consortium. Br J Sports Med 52(20): 1304-1310.

- Donken CCMA, Al-Khateeb H, Verhofstad MHJ, van Laarhoven CJHM (2012) Surgical versus conservative interventions for treating ankle fractures in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 15(8): CD008470.

- John JH, Annechien B, Ton AWJ, Gert JK (2010) Anatomy of the distal tibiofibular syndesmosis in adults: a pictorial essay with a multimodality approach. J Anat 17(6): 633-645.

- Hsu RY, Bariteau J (2013) Management of ankle fractures. R I Med J 96(5): 23-27.

- Massahud Junior MR, Mendes B, Líbero GA, Silva SB (2020) Quiropraxia na fisioterapia traumato-ortopé In: Associação Brasileira de Fisioterapia Traumato-Ortopédica. Silva MF, Barbosa RI, organizadores. (PROFISIO) Programa de Atualização em Fisioterapia Traumato-Ortopédica, Artmed Panamericana, Brazil, pp. 91-113.

- Sung W (2019) Individuals with and without low back pain use different motor control strategies to achieve spinal stiffness during the prone instability test. J Orthop Sport Phys Ther 49(12): 899-907.

- Oliveira CB (2018) Clinical practice guidelines for the management of non-specific low back pain in primary care: an updated overview. Eur Spine J 27(11): 2791-2803.

- Artioli DP, Bertolini GRF (2018) Mc Kenzie method in physiotherapy (diagnosis and mechanical therapy): Application of logical clinical reasoning and systematic review. J Phys Res 8: 368-376.

- Delitto A (2012) Low back pain: Clinical practice guidelines linked to the international classification of functioning, disability, and health from the Orthopaedic Section of the American Physical Therapy Association. J Orthop Sport Phys Ther 42: 1-81.

- Olson KA (2016) Manual Physical Therapy of The Spine (2nd edn), Elsevier.

- Araújo FX (2017) Mobilizações articulares: raciocínio clínico, aplicações e evidências atuais. In: Associação Brasileira de Fisioterapia Traumato-Ortopédica, Silva MF, Barbosa RI, organizadores. (PROFISIO) Programa de Atualização em Fisioterapia Traumato-Ortopédica: Artmed Panamericana, Brazil, pp. 93-134.

- Hing W, Hall T, Rivett D, Vicenzino B, Mulligan B (2015) The Mulligan Concept of Manual Therapy - Textbook of Techniques, Elsevier.