Comparison of the Deep Squat Pose to the Sit-Reach and Functional Movement Screen Active Straight-Leg Raise

David D Peterson1*, Matthias L Dewhurst1 and Kenneth J Blood1

Cedarville University, Cedarville, United States

Submission: January 29, 2022; Published: February 8, 2022

*Corresponding author: David D Peterson, Assistant Professor of Kinesiology, Cedarville University, Cedarville, United States

How to cite this article: David D P, Matthias L D, Kenneth J B. Comparison of the Deep Squat Pose to the Sit-Reach and Functional Movement Screen Active Straight-Leg Raise. J Yoga & Physio. 2022; 9(4): 555767. DOI:10.19080/JYP.2021.09.555767

Keywords: Physical fitness; Cardiovascular endurance; Muscular strength, Muscular endurance; Sit reach test; Straight leg raise

Abbreviations: SRT: Sit Reach Test; FMS: Functional Movement Screen; ASLR: Active Straight Leg Raise; DSP: Deep Squat Pose

Introduction

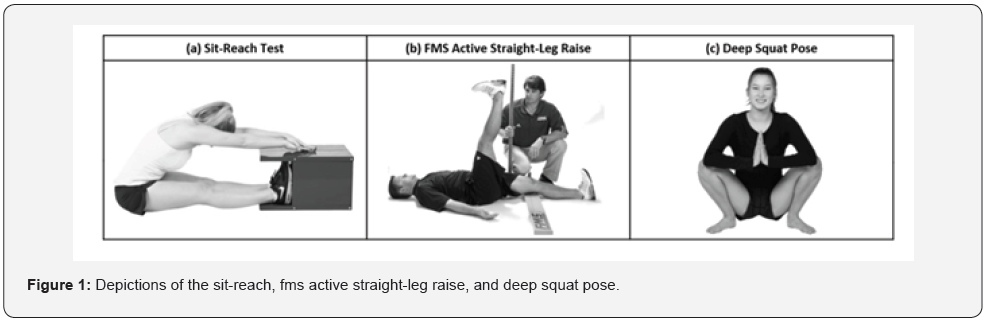

The five health-related components of physical fitness include cardiovascular endurance, muscular strength, muscular endurance, flexibility, and body composition. In terms of flexibility, there are currently a wide variety of tests and assessments used to measure flexibility. For example, the sit-reach test (SRT) has been used for decades in physical education, sport, and the military to assess low back and hamstring flexibility Hodgdon [1]. Despite its popularity, research suggests that although the SRT is an effective assessment of hamstring flexibility, it is not an effective assessment of low back flexibility [2,3]. As a result, alternative tests and assessments are often used to assess lower body flexibility. For example, the Functional Movement Screen (FMS) was developed in 1995 to evaluate the execution efficiency of specific movement patterns Cook [4]. One of the assessments included in the FMS is the active straight leg raise (ASLR), which evaluates both low back and hip mobility (both flexion and extension) as well as hamstring flexibility. Although not normally used as a formal assessment tool, research has shown yoga to be an effective means for improving flexibility Md Iftekher et al. [5]. Additionally, regular participation in yoga is associated with both short-term and long-term relief from chronic low back pain Cramer et al. [6]. One of the more popular poses in yoga for promoting improved mobility in the ankles, knees, hips and low back is the deep squat pose (DSP), also referred to as the Garland or Malasana pose. Similarly, Myer et al. [7] reported the squat is arguably one of most important movement patterns in terms of improving athletic performance, reducing injury risk, and supporting lifelong physical activity. Figure 1 provides a visual depiction of the SR, ASLR, and DSP.

The purpose of this study to was evaluate the effectiveness of the DSP as a formal method of assessing flexibility in the low back and hamstrings as compared to the ASLR and SRT.

Background

One of the general education (gen ed) courses offered at Cedarville University is PEF 1990 - Physical Activity and Healthy Living. In this course, students are required to perform a fitness pre-test (administered at the beginning of the semester) and a fitness post-test (administered at the end of the semester) to evaluate the various health-related components of physical fitness (excluding body composition). In terms of flexibility assessment, students performed the SRT. However, starting in the fall of 2021, the decision was made to replace the SRT with the DSP. The rationale for replacing the SRT was two-fold: 1) eliminate the need for specialized equipment for flexibility testing (i.e., sitreach box); and 2) provide students with a more comprehensive assessment of their lower body mobility and flexibility.

Methods

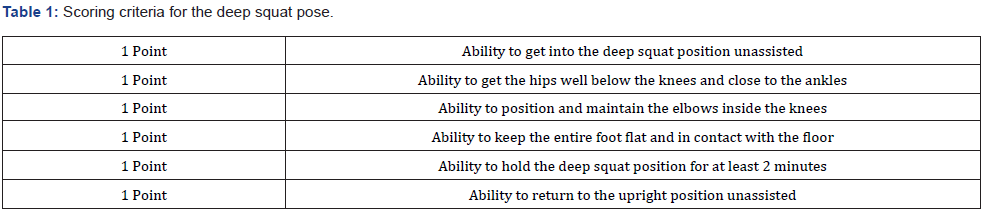

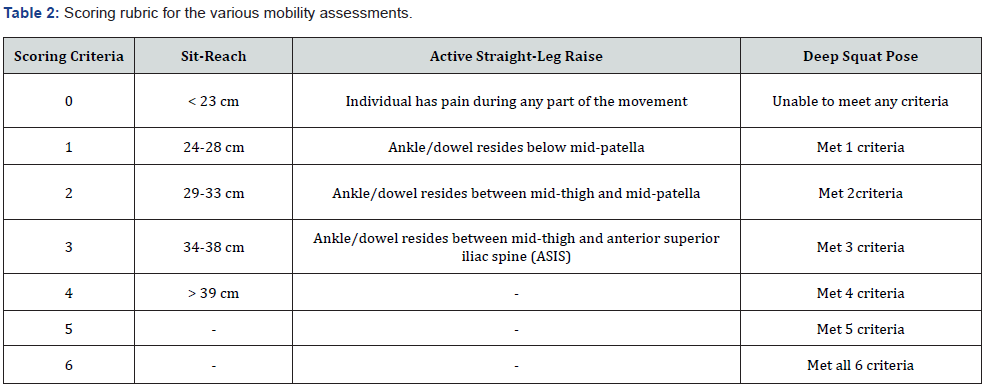

The study included 14 college-aged (i.e., 18-24) test subjects (13 male, 1 female) from Cedarville University. Eleven of the 13 male test subjects were on the Cedarville men’s soccer team (NCAA Div II). Institutional review board (IRB) approval was received, and all test subjects signed a consent form prior to participation. Data from each test subject was collected in three separate sessions. The first session consisted of signing the informed consent completion of the ASLR. The DSP and SRT were completed on the second and third session, respectively. Each session included a brief warm-up and lasted approximately 5-10 minutes. The warm-up consisted of 1-minute of jogging in place, five check marks (i.e., a dynamic warm-up exercise targeting the hamstring musculature) per leg, and a supine figure four stretch held for 15 seconds per each leg. The ASLR was completed by having each test subject lie flat on their back. The test subject would then raise one of their legs as high as possible while keeping one leg on the ground and both legs as straight as possible. Both the right and left leg were measured and graded on a scale ranging from 0-3. The DSP was completed by having the test subject squat as low as possible while keeping both feet flat on the floor and their elbows inside of their knees. Test subjects were asked to hold the DSP for 2 minutes. Performance was graded using a scale ranging from 0-6 scale. Specific criteria for the DSP are provided in Peterson et al. [8] Table 1.

The SRT was completed by having each test subject remove their shoes and place both feet flat against the sit-reach box. A non-adjustable sit-reach box was used for data collection. The test subject would reach as far as possible while keeping the legs straight. The best of three attempts was recorded using a studyspecific scale ranging from 0-4 scale based on data provided by Heyward & Gibson [9]. A side-by-side comparison of the scoring rubrics used for the ASLR, DSP, and SRT is provided in Table 2.

After each test subjects had completed all three sessions, their data was entered into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet and evaluated using a linear regression model to determine respective r2 values. Additionally, a residual plot line was developed comparing tests to each order to further determine correlation.

Results

Results showed a high correlation between the DSP and the ASLR (i.e., r2= 0.83 / p-value= 0.00000535), a modest correlation between the DSP and the SRT (r2= 0.46 / p-value= 0.00745), and a modest correlation between the ASLR and the SRT (r2= 0.67 / p-value= 0.000326). Plot lines comparing the DSP to the ASLR and SRT showed an even distribution of scores both above and below the expected trendline thereby also suggesting a modest correlation between tests.

Discussion

Results showed a strong correlation between the DSP and ASLR, which may allow for more widespread application since the FMS has been shown to be an effective method of identifying movement deficiencies and predicting injury risk [10,11]. Although the DSP and ASLR are both easy to administer, the DSP may be even more feasible as it can be performed without the use of a partner or any equipment. Since results showed a modest correlation between the DSP and SRT, the DSP is likely inferior to the SRT in terms of assessing hamstring flexibility independently. However, the DSP may be superior to both the ASLR and SRT in terms of assessing overall lower body mobility as performance is dependent on the range of motion in the ankles, knees, hips, and low back. Based on current findings, the DSP shows promise a potential new test for lower body mobility based on its high to modest correlation to other established tests as well as its overall feasibility and ease of administration.

Limitations

The study had several limitations. First, the study only involved 14 test subjects. Second, the study only used collegeaged test subjects. Third, the study consisted primarily of male test subjects. Finally, the majority of test subjects were collegiate soccer players. Further research is needed to better determine how age, gender, and fitness level may affect the correlation between the DSP and the ASLR and SRT.

References

- Hodgdon J (2000) A history of the U.S. Navy physical readiness program from 1976 to 1999. Technical Document No. 99-6F. Naval Health Research Center: San Diego, CA, USA.

- Castro PJ, Chillón P, Ortega F, Montesinos JL, Sjöström M, et al. (2009) Criterion-related validity of sit-and-reach and modified sit-and-reach test for estimating hamstring flexibility in children and adolescents aged 6-17 years. International Journal of Sports Medicine 30(9): 658-662.

- Liemohn W, Sharpe G, Wasserman J (1994) Criterion related validity of the sit-and-reach test. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 8(2): 91-94.

- Cook G (2001) Functional movement screen - ACSM.

- Md Iftekher SN, Bakhtiar M, Rahaman KS (2017) Effects of yoga on flexibility and balance: a quasi-experimental study. Asian Journal of Medical and Biological Research 3(2): 276-281.

- Cramer H, Lauche R, Haller H, Dobos G (2013) A systematic review and meta-analysis of yoga for low back pain. The Clinical Journal of Pain 29(5): 450-460.

- Myer G, Kushner A, Brent J, Schoenfeld B, Hugentobler J, et al. (2014) The back squat: a proposed assessment of functional deficits and technical factors that limit performance. Strength and conditioning journal 36(6): 4-27.

- Peterson D, Kimble J, Rogers T (2021) A Christian guide to body stewardship, diet and exercise. Cedrus Press.

- Heyward V, Gibson A (2014) Advanced Fitness Assessment and Exercise Prescription. Human Kinetics.

- Dorrel B, Long T, Shaffer S, Myer G (2015) Evaluation of the functional movement screen as an injury prediction tool among active adult populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports health 7(6): 532-537.

- Teyhen D, Shaffer S, Lorenson C, Halfpap J, Donofry D, et al. (2012) The functional movement screen: A reliability study. Journal of Orthopedic & Sports Physical Therapy 42(6): 530-540.