Motivational Interviewing in Physiotherapy for Patients with Low Back Pain: Effects on Adherence to Exercises and on Levels of Incapacity and Pain

Helena Ribeiro Rodrigues1 and Irene Palmares Carvalho2*

1S Martinho Hospital, University of Porto, Portugal

2Department of Clinical Neurosciences and Mental Health and CINTESIS, University of Porto, Portugal

Submission: November 10, 2021; Published: December 6, 2021

*Corresponding author: Irene Palmares Carvalho, Department of Clinical Neurosciences and Mental Health and CINTESIS, University of Porto, Portugal

How to cite this article: Helena R R, Irene Palmares C. Motivational Interviewing in Physiotherapy for Patients with Low Back Pain: Effects on Adherence to Exercises and on Levels of Incapacity and Pain. J Yoga & Physio. 2021; 9(2): 555758. DOI:10.19080/JYP.2021.09.555758

Abstract

Background. This study aimed to evaluate the efficacy of motivational interviewing (MI) on adherence to exercises and on levels of pain and disability among patients receiving physiotherapy for low back pain.

Methods. Sixty patients attending a 15-day program of physiotherapy for low back pain were allocated to experimental (EG) and control (CG) groups. A regular treatment of physiotherapy with at-home exercises was offered to all participants. On day seven, MI was applied to the EG. The CG received an anti-inflammatory information program. Outcomes were measured before and after the intervention. Data were analyzed with GLM Repeated Measures.

Results. Adherence to exercises increased significantly in the EG, decreasing in the CG. Both groups registered statistically important improvements in pain and disability. The decrease in these two outcomes was visibly more pronounced in the EG after MI, but differences between the two groups were non-significant.

Conclusions. One session of MI significantly increased adherence to exercises and yielded a trend toward declines in pain and disability among patients with low back pain. The effects on adherence to the exercises were significant after seven sessions of physiotherapy, and motivational interviewing can be trained and incorporated into routine physiotherapy sessions to overcome the frequent difficulties concerning patients’ adherence to exercises.

Keywords: Low back pain; Disability; Exercise; Motivational interviewing; Physiotherapy; Physical disability; Public health

Abbreviations: EG: Experimental; CG: Control; MI: Interviewing; CG: Control Gro

Introduction

Low back pain is a major cause of physical disability that represents an important public health problem due to its high prevalence, as well as associated health costs and loss of productivity [1-3]. The prevalence of this condition makes it a major problem around the world [4], and studies suggest that about 80% of the population will suffer from back pain during their active life [5]. The fact that depression and anxiety can appear associated with low back pain contributes to prolong this painful situation, causing distress, dissatisfaction and incapacity as regards both work and social life [6]. Low back pain is thus a common problem of considerable socio-economic importance [3]. The main group of disability factors in the origin of back pain includes posture, inadequate body movements, and safety and hygiene conditions at work that lead to anti-ergonomic activities capable of producing changes in the person’s spine [6]. Obesity, a sedentary lifestyle, weather changes and genetic factors also contribute to the onset and continuation of the lumbar symptoms [7]. Studies suggest that about 50% of back pain cases improve within a week, 90% in six weeks, and only seven to 10% of patients remain symptomatic for more than six months [7]. Despite these results and the large amount of research and time dedicated to the resolution of low back pain [8], this health problem does not always resolve permanently and may present a variable course and frequent recurrences [9]. Various therapeutic modalities are available to address back pain without recourse to surgery (e.g., physiotherapy, Cyriax, manual therapy), and all show similar degrees of effectiveness [2,5]. Drug therapy also allows temporary pain relief [4]. However, physiotherapy alone or in combination with other interventions (e.g., postural correction exercises, muscular strengthening, or stretching) is probably the most widely used treatment to reduce back pain [5,9]. For the treatment of low back pain, consensus exists about the importance of combining physiotherapy with exercises [10]. Exercise therapy can be defined as any program during the therapy sessions in which the participants are required to carry out repeated voluntary dynamic movements or static muscular contractions, where such exercises are intended as treatment [11]. The exercises vary in content and form of exposure and include whole-body exercises for general physical fitness, aerobic exercises for muscle strengthening, or flexibility and stretching exercises [12,13]. No specific exercise program has been pointed out as the most effective treatment. However, studies indicate that simple and short programs, customized to the needs of each patient and which fit into their daily routines without requiring extra time will be more effective [10,12]. Specifically, individually supervised exercises can relieve pain and improve physical function [12].

The positive effects of the exercises have been reported in several studies. For example, in a systematic literature review, the authors concluded that therapy consisting only of exercises reduces pain, though slightly, and improves physical function in patients with chronic low back pain [12]. However, one of the difficulties with exercise therapy is patients’ high levels of abandonment. Although encouragement, explanation, and information, namely regarding the possibility of early return to normal activities, are part of physiotherapists’ functions [9], the literature suggests that one to two thirds of patients do not adhere to the exercises [10]. The main factors identified as responsible for the dropouts are patient-related aspects (e.g., motivation and response to the physiotherapist’s proposals), physiotherapist-related factors (including ability to motivate the patient), the prescribed program, and misinterpretation of or forgetfulness about the instructions [10]. Other reasons could be the inconveniences associated with following programs’ fixed dates and times [9]. Failure to adhere occurs mainly when the supervised treatment is interrupted, because patients stop receiving their physiotherapist’s motivation and monitoring on their progress [10]. There are indications that the degree of compliance to the exercises is as low as in other health systems. Even if patients are informed and understand that the prescribed exercises will lead to the relief of symptoms, compliance tends to decrease over time [10]. To address this difficulty regarding patient adherence to exercise programs due to lack of motivation, several strategies have been suggested (e.g., encouraging patients to obtain the support of family or friends, calling them to show interest, and adjusting the choice of the exercises to patients, since motivation depends on their preferences) [9]. Motivational interviewing is a strategy that can be implemented to improve patients’ adherence to exercise programs. Proposed initially in the context of interventions in addictive behaviors, motivational interviewing has been extended to the promotion of behaviors considered to be healthy, such as adherence to diets or to physical activity, and to the reduction of habits considered to be unhealthy, such as those contributing to overweight [14]. Motivational interviewing is based on identifying and mobilizing the intrinsic values of the person with the goal of stimulating change in behaviors [15,16]. It aims to explore and resolve the person’s ambivalences and to help the person to gain awareness of the benefits and the costs associated with the behavior [15]. It acts through a state of readiness for change that is invoked, rather than imposed, on the patient [17]. For this change to occur, it is important that the person believes in his or her ability to change. The change is otherwise unlikely to happen [17]. Advice is given only with the person’s consent, and, when given, it is accompanied with incentives that encourage patients to actively make their own choices [17]. Despite the extensive application of motivational interviewing, few studies examine the effects of this strategy in physiotherapy programs for patients with low back pain [18]. Studies investigating the association between motivational interviewing and adherence to physical exercises tend to investigate other health areas that include heart disease [19], hip fracture [20], fibromyalgia [21,22], obesity, arthritis [23,24], diabetes [25] and cancer [26]. Several of these studies show the benefits of motivational interviewing in the adherence to physical exercise and in the improvement of health indicators. However, some also report lack of effects of using this strategy on the subjects’ adherence to physical activity [26], attributed to methodological issues (e.g., training of the professionals who applied motivational interviewing). In a meta-analysis on the effectiveness of motivational interviewing in adults with chronic pain, the authors reported a small to moderate effect of this intervention on increased adherence to treatment in the short run, as well as on pain, but suggested that the latter might be due to publication bias [27]. The few studies examining the effectiveness of motivational programs in physiotherapy combined with exercises for patients with low back pain show promising results. One of these studies showed that, in the absence of significant differences in measures of patients’ motivation (anxiety, locus of control, or attitude toward exercises), the level of participation in the exercise program increased in the group receiving motivational interviewing, and group differences in levels of disability over time followed a trend toward significance. Pain intensity also decreased significantly in both groups, although the difference over time between the group receiving motivational interviewing and the control group was non-significant [10]. In the other study, compliance with the exercises and physical function of patients with chronic low back pain improved significantly in the group receiving conventional physiotherapy with exercises associated with a motivational program, compared to the group receiving physiotherapy without motivational interviewing [18]. In some studies, these effects remained over time. Five years later, the improvements were still significant regarding the level of disability, pain intensity and ability to work in patients undergoing supervised exercises associated with the motivational program, compared to those who received only the standard exercise program without the motivational intervention [28, 29].

Other studies focusing on low back pain are based on strategies other than motivational interviewing. For example, in a study on the effects of an exercise program associated with cognitive behavioral training in patients with sub-acute low back pain, the authors found greater adherence to the exercises in the group receiving the cognitive-behavioral training program than in the group not receiving this training, though the level of pain did not decrease [30]. In another study, some physical improvement was observed in elderly people with chronic back pain undergoing a program of physiotherapy and exercises which included advice based on the transtheoretical model for behavior change, but the difference between the groups was non-significant [31,18]. On the contrary, the effectiveness of the model CHAMPS II (a lifestyle program based on the model of personal choice which promotes increased levels of physical activity) was tested with significant increases in the physical activity of an elderly population [32]. A more recent meta-analysis on the addition of motivational interventions (including motivational interviewing, cognitive behavioral therapy, social cognitive theory and social learning theory) to exercises and traditional physiotherapy showed no significant differences in exercise attendance between the groups, though activity limitation decreased in a variety of patients (e.g., sedentary women, patients with chronic back pain, cancer survivors and adults with obesity) [33]. Research on the effects of associating physiotherapy with exercises to motivational interviewing is scarce in the literature on low back pain [10], despite the high number of medical visits motivated by this condition, and the physical, psychological, and socio-economic impact of this problem [34]. The studies reviewed indicate that motivational interviewing seems more effective than other programs associated with the prescription of exercises regarding the improvement of pain, disability, and adherence to physical exercises. However, the effects of motivational interviewing on adherence to physical activity is not observed across all studies and call for more research.

This study examines the effects of motivational interviewing on adherence to exercises among patients with low back pain undergoing a physiotherapy program. Given the positive effects of the exercises on the improvement of patients’ back pain and physical function, levels of pain and disability also are inspected.

Methods

Sample

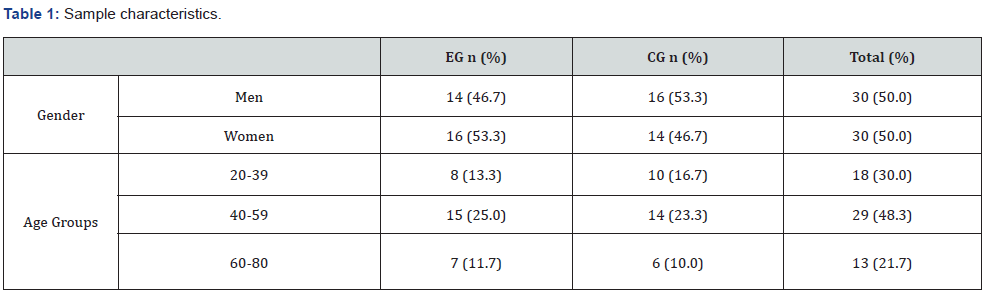

A sample of 60 adult patients with low back pain receiving physiotherapy treatment in a hospital located in a suburban area participated in the study. The sample’s ages ranged between 20 and 80 years old, and nearly half of the patients were men (Table 1). The hospital’s Ethics Committee approved the study. All participants were informed about the study and gave informed consent before data collection began.

EG: Experimental Group, CG: Control Group

Instruments

Patients’ level of incapacity was assessed with the Roland- Morris Disability Questionnaire (Portuguese adaptation), a widely used measure for low back pain. This questionnaire consists of 24 self-response questions about the interference of low back pain in the life of the patient [35]. The questions are marked as “yes” if present, and “no” if absent in patients’ daily lives. The result is the sum of “yes” answers, with a maximum score of 24 points and a minimum of zero. The closer the score is to 24, the greater the degree of incapacity. This questionnaire has shown high levels of internal consistency and of temporal stability and provides a reliable and valid measure of the incapacity of patients with low back pain [35]. Pain was assessed with the Verbal Pain Intensity Scale to accommodate older patients [36]. In this instrument, patients are asked to rate the intensity of their pain according to the following scale: none, mild, moderate, severe and maximum possible pain. This is a widely used scale worldwide that has also shown good sensitivity to differences in pain intensity among Portuguese samples [37]. Performance of physical activity was registered in the list of exercises that patients receive on their first day of treatment. The Exercises Table is an instrument with two entries consisting of five exercise types distributed throughout the 15 days of treatment (warm-up, gluteus, low back, and abdominal muscle strengthening, and low back muscle stretching). Patients were asked to “mark the exercises you do on this table every day, leaving those you do not do blank”. The maximum possible score in this Table is 70 points (when the patient has performed all the exercises every day over the 15 days), and the minimum score is 0 (when the patient did not exercise over this period of time). On the seventh day of treatment, the patient completes a maximum of 30 exercises (when all of them are performed every day). From days seven to 15, the maximum possible number of exercises performed is 40. To increase the accuracy of the responses, the physiotherapist checks the Exercises Table and verifies it daily with each patient.

Procedure

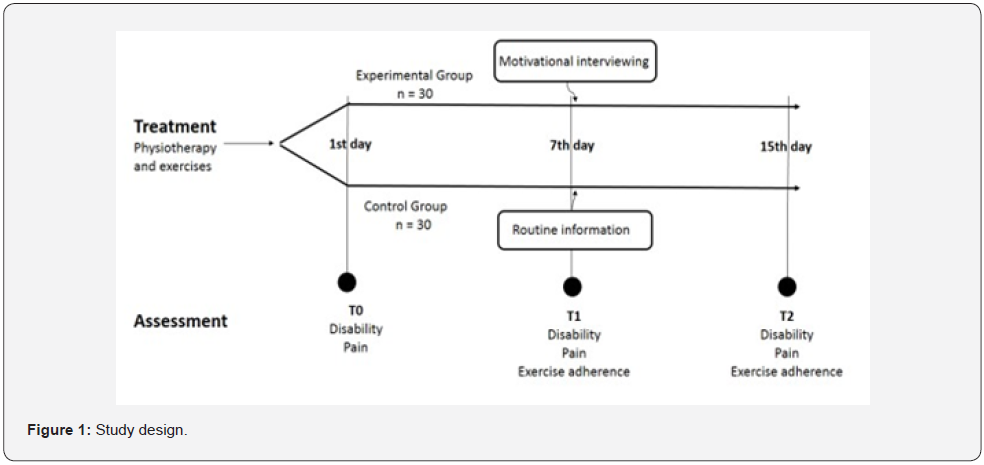

This study comprised 15 consecutive sessions of in-clinic physiotherapy associated with at-home physical exercises. Sixty patients were allocated to two groups by order of arrival, so that the first patient was placed in the experimental group (EG), the second patient in the control group (CG), and so on until each group had 30 participants. Patients were blind about the group to which they were allocated. Pain intensity and level of disability were assessed on days one (T0), seven (T1) and 15 (T2) of the physiotherapy programs. Frequency of the exercises performed at home was assessed once the physiotherapy program began, on days seven (T1) and 15 (T2). Patient attendance of the in-clinic physiotherapy sessions was also registered. The study design is outlined in Figure 1. A physiotherapist trained in motivational interviewing delivered the same program of physiotherapy plus exercises to all patients. Each patient was also given a table with a calendar of the different days of treatment and the corresponding list of exercises to be performed at home each day. The physiotherapist explained and demonstrated the exercises and informed patients about the importance of doing them. On the seventh day of the physiotherapy program, the physiotherapist applied motivational interviewing to the EG and spent the same amount of time giving routine information on anti-inflammatory medication to participants in the CG.

Analysis

The score of the Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire was obtained from the sum of “yes” answers. The Verbal Pain Intensity Scale was scored on a 1 to 5 Likert-type scale, representing an increase from less to more intense pain. The score in the Exercises Table was calculated by the sum of the different exercises performed each day. This sum was then added across all days and divided by the total number of exercises for the corresponding period (seven or 15 days), yielding the mean percentage for each group. Data were analyzed in SPSS with General Linear Model Repeated Measures procedures to assess participants’ adherence to the physical exercises, the intensity of pain and disability over time (T0, T1 and T2). Groups were compared at baseline (i.e., at T0 for levels of disability and pain, and at T1 for adherence to the exercises) with t-tests, using Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons (alpha=0.017).

Results

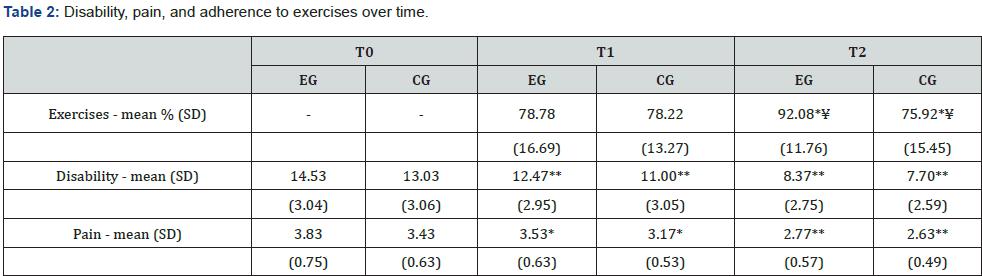

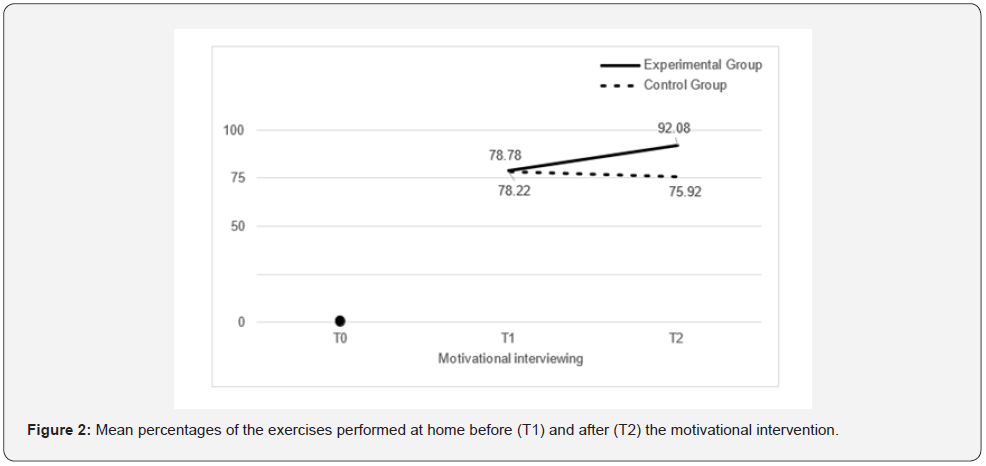

The EG and the CG were similar in patient composition (Table 1). Patients in both groups attended all physiotherapy sessions. The t-tests showed that, before the beginning of physiotherapy (at T0), the EG and the CG were identical (registering no statistically significant differences) in terms of reported levels of disability (M=14.53; SD=3.04 and M=13.03; SD=3.06, respectively) and pain (M=3.83; SD=0.75 and M=3.43; SD=0.63, respectively). Before the motivational program, participants performed a mean percentage of at-home physical exercises (at T1) that was similar for the EG (M=78.78; SD=16.69) and the CG (M=78.22; SD=13.27) (Table 2).

T0: Before the beginning of the physiotherapy treatment (and before the application of motivational interviewing), T1: Seven days into the physiotherapy treatment, application of motivational interviewing, T2: End of the Physiotherapy Treatment, EG: Experimental Group, CG: Control Group, SD: Standard Deviation, ¥ p<0.05: Differences between experimental and control groups, *p<0.05: Differences over time.

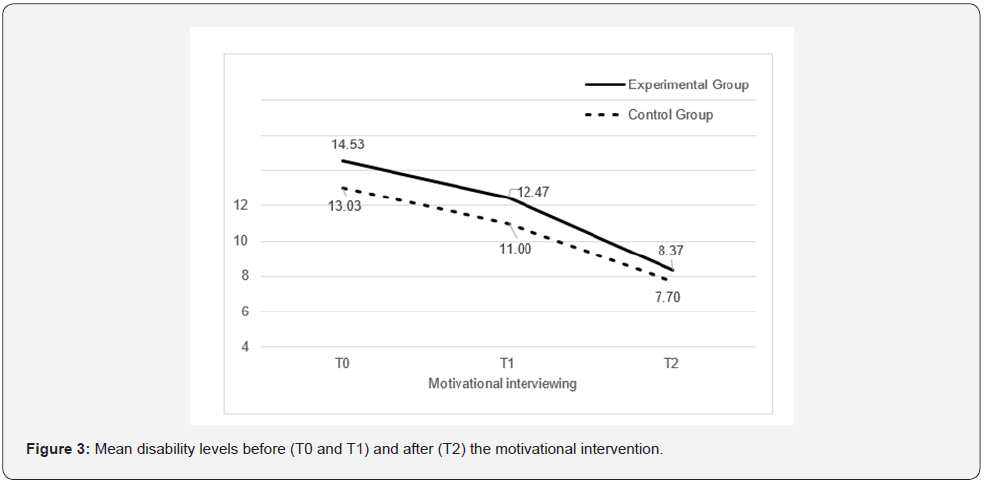

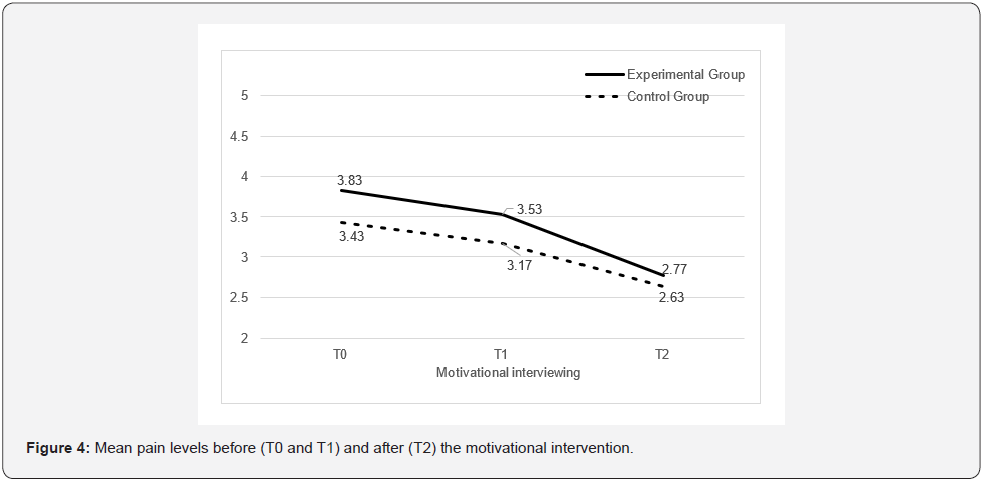

Effects of motivational interviewing on adherence to exercises, pain and disability

Adherence to physical exercises improved after the motivational intervention in the EG. In the same period, adherence to the exercises declined slightly in the CG (Figure 2). Within-subjects tests showed the highly significant effects of motivational interviewing on adherence to the exercises, F(2,116)=1385.193, p=0.000, η2=0.960. Within-subjects contrasts showed non-significant group-exercise interactions before the motivational interview, F(1,58)=0.021, p=0.885. However, this interaction became highly significant after the motivational intervention, F(1,58)=23.089, p=0.000, η2=0.285, indicating the presence of significant differences between the two groups regarding adherence to exercises. Figure 3 depicts the decline in reported disability levels for participants of the two groups as the physiotherapy sessions progressed, F(2,85)=206.510, p=0.000, η2=0.781 (Huynh-Feldt tests). Pairwise comparisons showed highly significant differences between disability at T0 and at T1 for both the EG (mean difference=2.07; CI=[1.43-2.70]; p=0.000) and the CG (mean difference=2.03, CI=[1.28-2.79]; p=0.000). However, after the motivational intervention (between T1 and T2) the decline was more pronounced for the EG, nearly doubling (mean difference=4.10; CI=[3.09-5.12]; p=0.000), than for the CG (mean difference=3.30; CI=[2.29-4.31]; p=0.000). Nevertheless, within-subjects contrasts showed non-significant group-disability interactions from T0 to T1, F(1,58)=0.007, p=0.932, or from T1 to T2, F(1,58)=2.010, p=0.162, suggesting that differences between the two groups were statistically non-significant even after the motivational intervention. A similar picture was observed for pain (Figure 4). Participants in both groups reported significantly less pain as the physiotherapy sessions progressed, F(2,116)=114.747, p=0.000, η2=0.664. Pairwise comparisons showed significant differences between pain at T0 and at T1 for both the EG (mean difference=0.30; CI= [0.08-0.52]; p=0.004) and the CG (mean difference=0.27; CI= [0.06-0.48]; p=0.009). However, after the motivational intervention (between T1 and T2), the decline was more pronounced in the EG, more than doubling (mean difference=0.77; CI= [0.57-0.97]; p=0.000), than in the CG (mean difference=0.53; CI= [0.30-0.77]; p=0.000). Nevertheless, withinsubjects contrasts showed non-significant group-pain interactions from T0 to T1, F(1, 58)=0.079, p=7.779, or from T1 to T2, F(1, 58)=3.691, p=0.060, indicating absence of statistical differences between the two groups even after the motivational intervention.

Discussion

In this study, two groups of patients with low back pain attending a 15-day physiotherapy treatment that included athome exercises were compared regarding adherence to the exercises and associated levels of disability and pain. On the 7th day of treatment, motivational interviewing was applied to the experimental group, and the control group received an information program. Motivational interviewing significantly increased adherence to at-home exercises. The decrease in pain and disability levels was also steeper for the experimental group, although differences from the control group were non-significant. The results are indicative of the positive effects that a program of physiotherapy associated with at-home physical exercises has on patients’ low back pain, as suggested in previous research [10,12]. Halfway through the treatment (at day seven), when patients were performing the at-home physical exercises without significant differences between the EG and the CG (before the motivational interviewing), significant improvements already were observed regarding levels of pain and disability in both the EG and the CG. After the motivational intervention, adherence to the exercises increased significantly in the EG and decreased slightly in the CG, with significant differences between the two groups regarding this outcome. In addition, the decrease in both pain and disability levels was noticeably more pronounced after the motivational intervention in the EG (at least the double) than before the motivational intervention. The decrease in pain and disability in the CG for the same period was comparatively more gradual. However, these trends toward decreased pain and disability in the EG did not reach significant differences from the CG, like in the previous studies on the efficacy of motivational programs on treatment outcomes of people with low back pain [10,18]. It is possible that sample size or program length (e.g., the short duration of the second half of the physiotherapy treatment) has prevented the emergence of significant effects on pain and disability, and that a bigger sample or a longer period of physiotherapy time would produce significant differences between the EG and the CG regarding also pain and disability. In addition, even though the same physiotherapist with extensive training in motivational interviewing applied this strategy in the physiotherapy sessions, minimizing intervention variation, outcomes might differ according to patients’ characteristics (e.g., type of back pain, sedentary lifestyle, attitude toward exercises, etc.) [33] that were not considered here. This study was also limited to the moment when physiotherapy was offered, and follow-up studies are needed to inspect how these results remain or change over time after this moment.

Though motivational interviewing effectively improved adherence to exercises, more studies are necessary to clarify its role in the decrease of pain and of disability among patients with low back pain, and specifically its indirect effects through increased adherence to exercises. Inspection of a minimum number of sessions necessary for interventions to be effective is also important (the shortest intervention yielding positive results found in a meta-analysis lasted 3.5 weeks) [33]. In our study, a single session of motivational interviewing was applied halfway through the 15 physiotherapy sessions. The following seven consecutive sessions were thus enough for visible effects to emerge regarding adherence to the exercises.

Conclusion

A single session of motivational interviewing significantly increased adherence to exercises and yielded steeper, though statistically non-significant, declines in pain and disability among patients with low back pain. Motivational interviewing thus yields promising results regarding adherence to at-home exercises, disability and pain, and physiotherapists can be trained to incorporate motivational interviewing into their routine physiotherapy sessions to overcome the frequent difficulties concerning patients’ adherence to exercises.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate: All procedures performed in the study were approved by the Ethics Committee of S. Martinho Hospital and were in agreement with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- Wu A, March L, Zheng X (2020) Global low back pain prevalence and years lived with disability from 1990 to 2017: estimates from the Global Burden of Disease Study. Ann Transl Med 8(6): 299.

- Cherkin DC, Deyo RA, Battie M, Street J, Barlow WA (1998) comparison of physical therapy, chiropractic manipulation, and provision of an educational booklet for the treatment of patients with low back pain. N Engl Journal Med 339(15): 1021-1029.

- Sokunbi O, Cross V, Watt P, Moore A (2010) Experiences of individuals with chronic low back pain during and after their participation in a spinal stabilisation exercise programme - a pilot qualitative study. Man Ther 15(2): 179-184.

- Hoy D, Bain C, Williams G, March L, Brooks P et al. (2012) A systematic review of the global prevalence of low back pain. Arthritis Rheum 64(6): 2028-2037.

- Koes BW, Bouter LM, Beckerman H, van der Heijden GJ, Knipschild PG (1991) Physiotherapy exercises and back pain: a blinded review. BMJ 1991; 302(6792): 1572-1576.

- Caraviello EZ, Wasserstein S, Chamlian TR, Masiero D (2005) Avaliação da dor e função de pacientes com lombalgia tratados com um programa de Escola de Coluna. Acta Fisiatrica 12(1): 11-14.

- Trevisani VF, Atallah AN (2003) Lombalgias: evidências para o tratamento. Revista Diagnóstico e Tratamento 8(1): 17-19.

- Henschke N, Maher CG, Refshauge KM, Das A, McAuley JH (2007) Low back pain research priorities: a survey of primary care practitioners. BMC Fam Pract 8: 40.

- Moffett J, McLean S (2006) The role of physiotherapy in the management of nonspecific back pain and neck pain. Rheumatology (Oxford) 45(4): 371-378.

- Friedrich M, Gittler G, Halberstadt Y, Cermak T, Heiller I (1998) Combined exercise and motivation program: effect on the compliance and level of disability of patients with chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 79(5): 475-487.

- Bekkering G, Hendriks H, Koes B (2003) Dutch physiotherapy guidelines for low back pain. Physiotherapy 89(2): 82-96.

- Hayden JA, van Tulder MW, Tomlinson G (2005) Systematic review: strategies for using exercise therapy to improve outcomes in chronic low back pain. Ann Intern Med 142(9): 776-785.

- Medina-Mirapeix F, Escolar-Reina P, Gascon-Canovas JJ, Montilla-Herrador J, Jimeno-Serrano FJ, et al. (2009) Predictive factors of adherence to frequency and duration components in home exercise programs for neck and low back pain: an observational study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 10: 155.

- Rollnick S, Allison J (2004) Motivational interviewing. The essential handbook of treatment and prevention of alcohol problems, Wiley & Sons, West Sussex, UK, pp. 105-115.

- Rubak S, Sandbaek A, Lauritzen T,Christensen B (2005) Motivational interviewing: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Gen Pract 55(513): 305-312.

- Hettema J, Steele J, Miller WR (2005) Motivational interviewing. Ann Rev Clin Psychol 1: 91-111.

- Britt E, Blampied NM, Hudson SM (2003) Motivational interviewing: a review. Australian Psychologist 38(3): 193-201.

- Vong SK, Cheing GL, Chan F, So EM, Chan CC (2011) Motivational enhancement therapy in addition to physical therapy improves motivational factors and treatment outcomes in people with low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 92(2): 176-183.

- Brodie DA, Inoue A, Shaw DG (2008) Motivational interviewing to change quality of life for people with chronic heart failure: a randomised controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud 45(4): 489-500.

- Resnick B, Orwig D, Wehren L, Zimmerman S, Simpson M, et al. (2005) The Exercise Plus Program for older women post hip fracture: participant perspectives. Gerontologist 45(4): 539-544.

- Jones KD, Burckhardt CS, Bennett JA (2004) Motivational interviewing may encourage exercise in persons with fibromyalgia by enhancing self-efficacy. Arthritis Rheum 51(5): 864-867.

- Ang DC, Kaleth AS, Bigatti S, Mazzuca S, Saha C, et al. (2011) Research to Encourage Exercise for Fibromyalgia (REEF): use of motivational interviewing design and method. Contemp Clin Trials 32(1): 59-68.

- Carels RA, Darby L, Cacciapaglia HM, Konrad K, Coit C, et al. (2007) Using motivational interviewing as a supplement to obesity treatment: a stepped-care approach. Health Psychol 26(3): 369-674.

- Ehrlich-Jones L, Mallinson T, Fischer H, Bateman J, Semanik PA, et al. (2010) Increasing physical activity in patients with arthritis: a tailored health promotion program. Chronic Illness 6(4): 272-281.

- Heinrich E, Candel MJ, Schaper NC, de Vries NK (2010) Effect evaluation of a Motivational Interviewing based counselling strategy in diabetes care. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 90(3): 270-278.

- Campbell MK, Carr C, Devellis B, Switzer B, Biddle A, et al. (2009) A randomized trial of tailoring and motivational interviewing to promote fruit and vegetable consumption for cancer prevention and control. Ann Behav Med 38(2): 71-85.

- Alperstein D, Sharpe L (2016) The efficacy of motivational interviewing in adults with chronic pain: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Journal Pain 17(4): 393-403.

- Smith C, Grimmer Somers K (2010) The treatment effect of exercise programmes for chronic low back pain. J Eval Clin Pract 16(3): 484-491.

- Friedrich M, Gittler G, Arendasy M, Friedrich KM (2005) Long-term effect of a combined exercise and motivational program on the level of disability of patients with chronic low back pain. Randomized Controlled Trial 30(9): 995-1000.

- Göhner W, Schlicht W (2006) Preventing chronic back pain: evaluation of a the or based cognitive-behavioural training programme for patients with subacute back pain. Patient Educ Couns 64(1-3): 87-95.

- Basler HD, Bertalanffy H, Quint S, Wilke A, Wolf U (2007) TTM-based counselling in physiotherapy does not contribute to an increase of adherence to activity recommendations in older adults with chronic low back pain-a randomised controlled trial. Eur J Pain 11(1): 31-37.

- Stewart AL, Verboncoeur CJ, McLellan BY, Gillis DE, Rush S, et al. (2001) Physical activity outcomes of CHAMPS II: a physical activity promotion program for older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 56(8): M465-470.

- McGrane N, Galvin R, Cusack T, Stokes E (2015) Addition of motivational interventions to exercise and traditional Physiotherapy: a review and meta-analysis. Physiotherapy 101: 1-12.

- Ponte C (2005) Lombalgia em cuidados de saúde primá Sua relação com características sociodemográficas. Rev Port Clin Geral 21: 259-267.

- Monteiro J, Faisca L, Nunes O and Hipólito J (2010) Roland Morris disability questionnaire - adaptation and validation for the Portuguese speaking patients with back pain. Acta Med Port 23(5): 761-766.

- Closs SJ, Barr B, Briggs M, Cash K, Seers K (2004) A Comparison of five pain assessment scales for nursing home residents with varying degrees of cognitive impairment. J Pain Symptom Manage 27(3): 196-205.

- Ferreira-Valente MA, Pais-Ribeiro JL, Jensen MP (2011) Validity of four pain intensity rating scales. Pain 152(10): 2399-2404.