A Manualized Yoga Intervention for Adolescents with Co-Occurring Physical and Psychiatric Conditions Shows Improvements in Mental and Physical Health

*Marianne Z Wamboldt1, Lisa C Kaley-Isley2, Michelle Fury3 and Patricia Hansen4

1Department of Psychiatry, The University of Colorado School of Medicine, USA

2Lisa C Kaley-Isley, E-RYT, Yoga campus, UK

3Michelle Fury, C-IAYT, Children’s Hospital Colorado, USA

4Patricia Hansen, E - CYT, Prana Yoga and Ayurveda Mandala Training Center, USA

Submission: August 08, 2018; Published: January 16, 2019

*Corresponding author: Marianne Z Wamboldt, Department of Psychiatry, The University of Colorado School of Medicine, USA

How to cite this article: Marianne Z W, Lisa C K-I, Michelle F, Patricia H. A Manualized Yoga Intervention for Adolescents with Co-Occurring Physical and Psychiatric Conditions Shows Improvements in Mental and Physical Health. J Yoga & Physio. 2019; 6(5): 555698. DOI: 10.19080/JYP.2019.06.555698

Abstract

This study addresses feasibility, acceptability and preliminary outcomes of a manualized yoga intervention for adolescents with co-occurring physical and psychiatric conditions in an academic medical setting. Participants (N=42; 83% female; 86% Caucasian; mean age 15.0 years) were adolescents whose self or parent report on the Behavioral Assessment Scale for Children (BASC) indicated clinical elevations in anxiety, depression and/or somatization symptoms. The intervention consisted of 8 weekly 150-minute group yoga classes, integrating asana, pranayama, relaxation (including yoga Indra), meditation and weekly home practice review. The majority of participants (83%) completed 6 or more classes and 32 participants (72%) completed the final assessments. Participants who completed the follow up assessments did not differ significantly at baseline from those who consented to participate in study but did not complete follow up assessments (by gender, age, race, parent marital status, teen or parent questionnaire reports). Participants who completed the follow up measures reported significant decreases in perceived stress (p<0.001); improvements in BASC anxiety, depression and somatization symptoms (all p<0.01); decreased functional disability (p<.01); and exhibited increased physical fitness (6-minute walk; p<0.01). A significant proportion shifted in their Readiness to Change “How I deal with stress” from “Contemplative” to “Action” stage (p<0.01). Parents reported improved child functional ability (p<0.01); improvement in BASC anxiety (p < 0.001), depression (p < 0.001), and somatization symptoms (p < 0.05). A manualized 8-week integrated yoga intervention for adolescents achieved clinically significant outcomes with moderately high adherence.

Keywords: Yoga; Adolescents; Manualized intervention; Anxiety; Depression

Abbrevations: BASC: Behavioral Assessment Scale for Children; HPA: Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal; SNS: Sympathetic Nervous System; NHIS: National Health Interview Survey; HPA: Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal

Introduction

This work was done in a children’s hospital setting, where there are numerous youth who suffer from both medical and co-morbid psychiatric conditions. These patients are often difficult to treat in western medicine settings, which tend to separate medical care from mental health care. Often physical symptoms and medical treatments exacerbate symptoms of anxiety and depression, and psychiatric symptoms in turn make treatment of medical illness more difficult. Teens with multiple disorders can be discouraged by lack of improvement, which can lead to non-adherence with prescribed treatments, and a sense of low self-efficacy.

Yoga is one of the most common complementary or alternative medicine interventions utilized by youth [1] As reported in the 2007 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), yoga was used for the control and reduction of anxiety and stress (31.4%), asthma (16.2%), and back/neck pain (15.3%) in youth ages 4 - 17 years of age. Comparing the 2007 to the 2012 NHIS, the use of yoga for children ages 4 - 17 increased from 2.3% in 2007 to 3.1% in 2012[2]. There are many theoretical reasons why yoga may be helpful in a variety of health conditions. Current data are suggestive of a possible value of meditation and mindfulness techniques for treating symptomatic anxiety, depression, and pain in youth [3]. In a meta-analysis Ross and Thomas [4] reviewed 81 studies and found “a growing body of evidence supports the belief that yoga benefits physical and mental health via down-regulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and the sympathetic nervous system (SNS).” For these reasons, in our clinical practice we have often recommended yoga to youth with chronic pain concerns, anxiety or mood problems. However, many community group yoga classes are geared to either adults or younger children, so it is often difficult to refer adolescents to yoga in the community.

Despite theoretical reasons why yoga may be helpful for adolescents with a variety of physical and mental health complaints, there have been far fewer studies documenting yoga intervention outcomes with this age group than there have been with adults. The studies that have been conducted have used a variety of interventions, which differ significantly enough to lack comparability. Two different groups have demonstrated that it is feasible to offer yoga to children hospitalized for cancer treatment [5,6]. One children’s hospital utilizes Iyengar Yoga in the Pain Clinic [7,8]. Another group has shown yoga to be an effective adjunctive treatment for outpatient children being treated for PTSD [9]. Nidhi and associates [10] were able to recruit adolescents with polycystic ovarian syndrome from a residential treatment center and showed that yoga improved endocrine parameters significantly better than a physical exercise control. Evans and colleagues offered 18 sessions of Iyengar yoga plus treatment as usual compared to treatment as usual for adolescents with irritable bowel syndrome and showed improvements in overall physical symptoms, although the attrition rate was high and the adherence rate to attendance at class and practice were quite low [7,11]. In preparation for this manualized intervention, we piloted an IRB approved feasibility study. We partnered with a Yoga Therapist with extensive experience in teaching yoga to persons with a variety of physical and psychiatric symptoms, and she designed a basic gentle Hatha Yoga approach, varying some poses depending on the attendees in class. We offered three onehour yoga classes per week and asked participants to attend at least 40 classes within a 6-month time frame, similar to what community yoga centers would offer. Health care providers did refer medically and psychiatrically ill adolescents to the study (N=77), some of whom (19%) were excluded due to young age, chronic infectious condition, or intellectual disability. Of the 62 eligible adolescents, only 36 (58%) consented to participate in the study. Of these 36, 72% had a chronic medical condition, 17% had 2 diagnoses, and 11% had 3 or more conditions. Developing a yoga practice that appealed to teens involved adapting the language and examples for instruction and providing a variety of guided relaxation scripts to keep their interest. Attendance was difficult: 8 (22%) never attended a class; 17 (47%) attended 1 - 10 classes; and only 8 (22%) attended 11 or more classes and completed one follow up data collection. From this experience we learned that transportation was a significant obstacle to attendance for nondriving teens, especially when they were asked to attend multiple sessions per week. We determined that a manualized study should occur in a more definitive time frame and over fewer sessions, similar to other extracurricular activities for school age teens.

The purposes of this current study were to determine whether adolescents with medical and psychiatric disorders would attend a time limited outpatient yoga intervention within the auspices of a hospital setting. We developed a manualized intervention and we wanted to replicate it multiple times to assess acceptability and generalizability. Finally, we aimed to gather preliminary outcome data to evaluate efficacy of the intervention with this population. The hypotheses and aims for the current study were as follows:

a. Greater than 50% of the enrolled participants will complete at least 20 hours of yoga classes;

b. Participants will report more readiness to change in their approach to stress management;

c. Participants will report decreased levels of stress as measured by the Perceived Stress Scale;

d. Participants will report decreased levels of anxiety, depression and somatization as measured by the BASC (self and parent report);

e. Participants will report increased levels of functional ability as measured by the Functional Disability Inventory (self and parent report);

f. Participants will demonstrate improved cardiovascular health as measured by the standardized 6 Minute Walk Test.

Materials and Methods

Participants

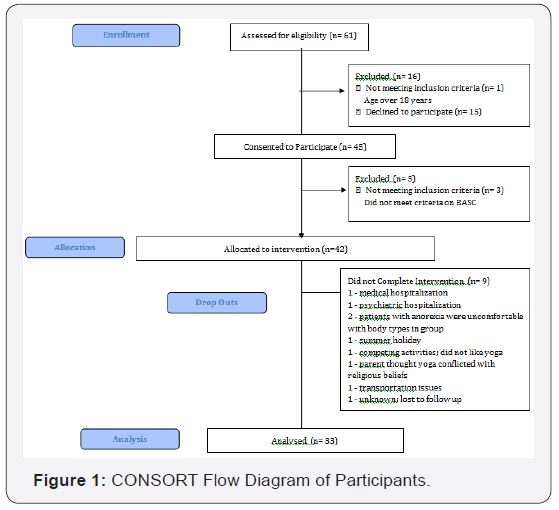

The Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board (COMIRB) approved both the pilot feasibility study and this intervention study. Participants were recruited over a 4-year period via communications with pediatricians and health care providers, local newspaper advertisements and an invited TV interview. Inclusion criteria were youth between ages 12-18 years; diagnosed with a physical and/or mental health condition by a health care provider; English speaking; with a self and/or parent report of clinical at-risk range (T score60) in at least one of the following BASC [12] subscales: Anxiety, Depression or Somatization. Exclusion criteria included pregnancy; primary substance abuse disorder; intellectual disabilities making it difficult to understand group instructions; and known positive testing for Methicillin- Resistant Staphylococcus Aurea’s. As can be seen in Figure 1, 61 adolescents were referred to the study. Of these, 15 declined to consent and 1 was out of the age group. An additional 3 who consented did not meet inclusion or exclusion criteria. A total of 42 adolescents completed baseline measures and attended at least one class; 35 attended 6 or more classes; and 32 completed follow up measures.

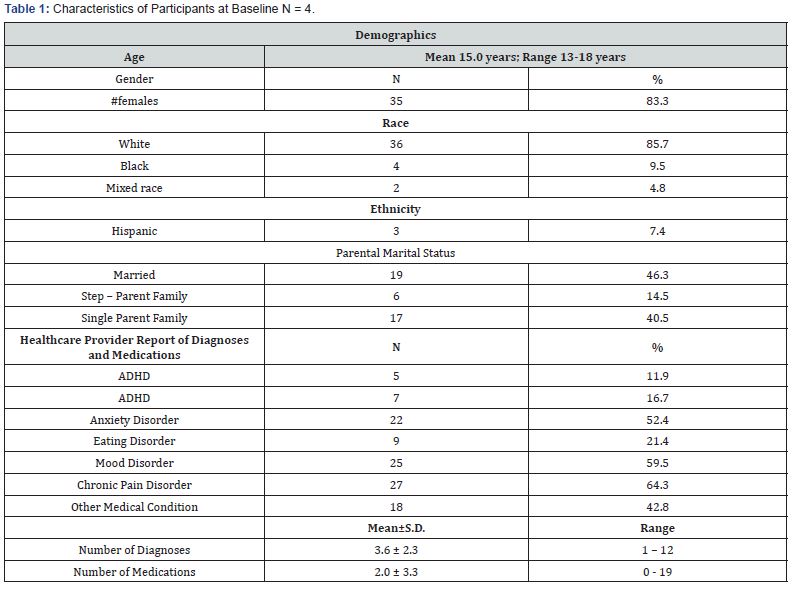

The 42 participants were 83% female; 86% White, 5% Black, and 9% Mixed Race; 7% identified as Hispanic; and on average were 15.0 years old (range 12.1 to 18.0). Table 1 depicts the characteristics of the participants, with medical information gathered from their health care provider, parent, and self. This was a group of adolescents with complex comorbid conditions, with 67% carrying three or more diagnoses. Only 36% of the group was not prescribed medications; 26% were prescribed 3 or more medications. Medications included antidepressants (31%), anxiolytics (5%), other psychotropics (31%), pain medications (14%) and medications pertaining to medical conditions (24%).

Procedures

The teachers of the yoga intervention were certified yoga teachers with over 500 hours of teacher training, as well as being licensed mental health professionals working within a children’s hospital. There was hospital funding for the time these teachers gave to the intervention. The research procedures were performed with minimal funding through the Ponzio Creative Arts Therapy endowment fund of the hospital. Thus, the pace of recruitment and yoga intervention was limited by funding, and recruitment took place over 4 years.

Names of potential participants were obtained via physician referral or self-referral. Parents (or legal guardian) of potential participants were contacted by telephone and provided with basic information about the study, then were maintained on a waiting list. In the two weeks prior to the start of an eight-week session, parents and participants met with one of the yoga teachers and research staff and were given a detailed description of the study prior to obtaining informed consent. Parents signed consent and adolescents signed assent. Following consent, participants and one parent completed the baseline questionnaires. The post intervention parent and self-report measures were completed on the day of the last yoga class. The fitness measure was completed on the first and last days of the yoga class.

Measures

Demographic questionnaire: Parents completed information on the teen’s medical history, medications, current diagnoses, age, ethnicity, parental marital status, and a release of information to communicate with both medical and mental health care providers. Treating physicians were asked to provide confirmation of diagnoses and medications and indicate if there were any contraindications for participation in yoga.

Functional disability inventory: (FDI, [13]): a 15-item questionnaire addressing the youth’s ability to perform normal daily activities such as walking upstairs, being at school all day, and getting to sleep at night. It is widely used with pediatric patients who suffer from a variety of chronic illnesses. The parent version (P-FDI) includes identical items but instructs the parent to rate their child’s functional ability. Respondents endorse items on a 5 point summative scale describing the amount of “trouble or difficulty” s/he has had in doing the listed activities in the last two weeks ranging from “no trouble,” to “impossible.” Total scores range from 0 to 60, with higher scores indicating more difficulty with function.

Behavioral assessment system for children: BASC [14,15], a 126-item parent rating scale and a 186-item teen self-report rating scale designed to screen for common mental health problems in children and adolescents. The parent form yields five composite factors and 11 subscales. The adolescent version also yields five composite factors and 14 subscales. Ratings with a t-score greater than 70 are described as clinically significant, which suggests “a high level of maladjustment.” Ratings with a t-score between 60 and 69 are labeled “at risk,” which is interpreted to mean “either a significant problem that may not be severe enough to require formal treatment or a potential of developing a problem that needs careful monitoring” [15].

Perceived stress scale (PSS, [15]). : This 10-item questionnaire measures the degree to which situations in one’s life are appraised as stressful. Items were designed to assess how unpredictable, uncontrollable, and overloaded respondents find their lives to be. Higher scores indicate higher levels of stress.

Readiness to change [16,17]: Based on the well-established model of change developed by Prochaska and colleagues, this questionnaire is modified for adolescent language. The primary question asked is how ready the teen is to change the way that they deal with stress.

Six-minute walk -A standardized assessment of cardiovascular health by documenting how far a participant could walk in 6 minutes, while simultaneously monitoring their heart rate (HR) and pulse oximetry (% O2 saturation). This test is frequently utilized for patients with cardiac, rheumatologic and respiratory disorders.

Yoga procedures

The design of the yoga intervention utilized findings from the pilot study, as well as considerations from the established Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) intervention developed by John Kabat-Zinn and colleagues [17]. Components of MBSR that we integrated into this intervention included the timing of weekly 2.5-hour sessions to provide a larger “dose” of yoga while decreasing the need for frequent transportation, the inclusion of psycho-education, processing of homework experiences, and using a mix of yoga, relaxation, breathing and meditation. The MBSR curriculum was modified: 1) to utilize language and concepts appropriate to adolescents, and 2) to be guided by Hatha Yoga concepts. Practically speaking, this led to an intervention with yoga poses and sequences that we identified were beneficial to teens in our pilot study, use of yoga Indra rather than a “body scan” for guided relaxation, a wider variety of pranayama (breathing practices) and more active and guided meditation practices to retain adolescent attention. Due to their developmental age, we scaffolded the teens’ skills at self-reflection by having them report their present moment stress levels, utilizing a 0-10 SUDs scale, at the start and end of each yoga session. This taught them to reflect on their current state, provided the yoga teacher information about their state, and allowed both yoga teacher and student to identify the practices that helped them change their stress levels.

The intervention was set up as a series of 8 closed groups of 4-8 participants each. Each group met for 2.5 hours weekly for a total of 8 weeks. Groups were held in the Children’s Hospital Colorado yoga room or in the gym of a local middle school. The structure and actual poses of each class were manualized (see Appendix A for details) and based on an adaptation of Rod Stryker’s am and pm practice DVD. We taught an activating 30minute practice that participants could use in the mornings as well as a calming 30minute practice for them to use in the evening. Classes included some psycho-education about stress, the autonomic nervous system, and how yoga may help modulate the stress response. Youth were asked to consider what yoga practices had helped them deal with stress the prior week and share with the group. A goal of the group intervention was to help participants learn from each other and build a sense of group belonging, both of which could improve adherence to the practices. Participants were asked to practice homework at least five days per week and were provided CDs of the yoga Indra guided relaxation as well as DVDs of the yoga sequences to facilitate home practice.

Data analysis

All data was cleaned and entered twice into JMP® Pro 14.1.0 for data analysis. Distributions for continuous variables were performed and means and variances established. For comparison of baseline data to follow up, paired t-tests were utilized for continuous variables and chi-square tests were utilized for categorical variables.

Results

Hypothesis 1 proposed that greater than 50% of the enrolled participants would complete 20 hours of yoga classes, by attending all eight, 2.5-hour long sessions. This was not supported, as only 38% of the sample attended all 8 classes. However, 83% attended 6 or more classes. Additionally, many of the teens reported doing home practice, which increased as they had more experience in the classes. Although we asked them to report on whether or not they did home practices, we had no way to quantitate how much time they spent, so cannot test what percentage of teens actually acquired 20 hours or more of yoga practice over the 8-week period.

As stated above, only 32 participants (76.1% of total) were able to be present at the last session where follow up assessments were gathered. We tested the baseline differences between those that consented but did not fill out follow up assessments (N= 0) versus those that completed follow up assessments (N = 32) on the following variables: age, gender, race, numbers of diagnoses, parents’ marital status, BASC scores on anxiety, depression and somatization as reported by teens and by their parents, FDI as reported by parents and teens, teen reported stages of change, and measures of the 6 minute walk. None of these were statistically significantly different. The remaining hypotheses looking at changes from baseline to after the intervention were tested on the 32 participants with both baseline and follow up data.

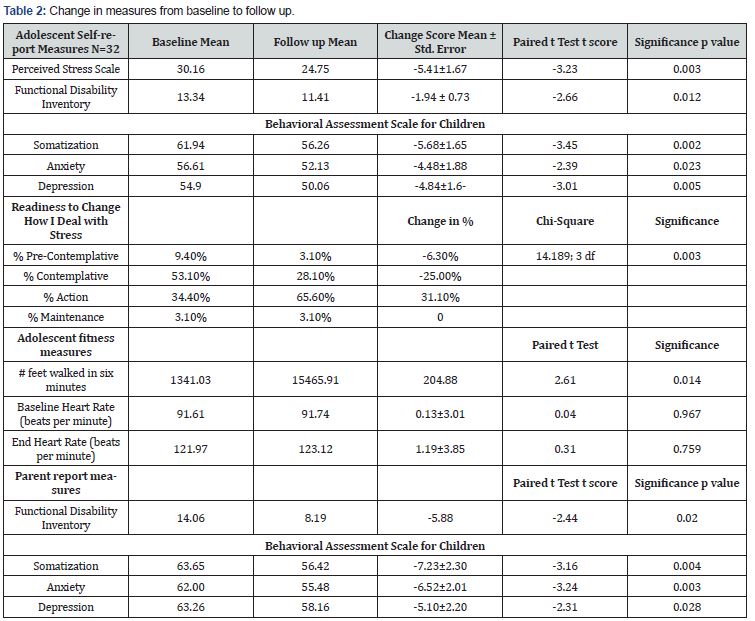

As can be seen in Table 2, the remaining Hypotheses were all supported with the data. Youth reported significantly decreased levels of stress as measured by the Perceived Stress Scale, and lower levels of anxiety, depression and somatization symptoms as reported on the BASC. The BASC scores are t-scores, and typically a change of 5 indicates a change of half a standard deviation, usually seen to be clinically significant. Most of the participant reported scores changed by just slightly less than 5 points but were statistically significant. Additionally, youth reported significantly less functional disability, indicating more ability to manage daily skills such as getting adequate sleep, climbing stairs and attending school. As far as motivation to use new strategies to help deal with stress, significantly more teens moved from the “Pre-contemplative” or “Contemplative” stage of change to the “Action” stage of change after the yoga intervention (Chi2=14.189; p=0.0027). By the end of the intervention, two thirds of the sample reported they were taking action toward changing how they deal with their stress.

Parents’ perspectives mirrored these findings, as they reported significantly less depression, anxiety, and somatization symptoms in their child, as well as decreased functional disability. Parents did report higher levels of symptoms on the BASC about their children, and the change scores they reported were clinically significant. Finally, in the objective measure of physical health, participants demonstrated improved cardiovascular health on the standardized 6 Minute walk test, with having walked significantly farther in the time allotted without having a significant change in heart rate. This sis a standardized tool used by physical therapists in helping patients with medical illnesses and is clinically significant in that many of the participants in the study had chronic medical illnesses.

Discussion

This open clinical trial of structured (manualized) yoga for youth with co-occurring medical and psychiatric problems showed statistically significant positive clinical changes in all the domains that were assessed by self-report, parent report and cardiovascular testing. This population was very complex, with 64% in treatment for a chronic pain condition; 7% being treated for an atopic condition; and over 40% being treated for other medical conditions. Additionally, anxiety and mood disorders were common comorbidities (52% and 59% respectively), and a fifth of the population (21%) suffered from an eating disorder severe enough to require inpatient treatment. These patients were all in existing western medical treatment programs and were referred due to having continuing levels of distress and dysfunction. While we did not reach our target level of at least 50% of participants receiving 20 hours of supervised yoga practice, given the severity of problems in this population, the adherence level we obtained indicated how helpful this intervention was perceived to be by participants and their families.

An important finding from this trial, compared to our pilot study and other published work, was that youth are more likely to attend scheduled weekly yoga classes, rather than be given the more adult model of “drop in” on an unscheduled basis. We demonstrated that youth would attend fewer, but longer length, classes. Based on qualitative comments documented after each class by the yoga teachers, there were no complaints about the class duration. Youth reported liking the fact that activities shifted every 30 minutes. Having a set number of sessions and up-front commitment from parents to specific days and times made transportation easier for parents to manage, and parents did not complain about the “wait time,” which was similar to what parents do when their children are in sports or other activities.

This age also did well with more structured home practice expectations, following up each class as to whether they completed “homework,” and congratulations when they made changes. Use of DVDs of yoga sequences and CDs of yoga nidra and other visualization meditations were helpful in increasing adherence to home practice. Utilizing a “check in” prior to starting the next yoga class further encouraged adherence, and also facilitated a sense of supportive peer pressure to continue working on new methods of dealing with stress. Within the small group, we problem solved obstacles to practice, e.g., how to find an uninterrupted space and time in the house to practice, how to have equipment at each (divorced) parents’ home, and how to juggle competing time demands to allow yoga practice. Additionally, we problem solved ways to integrate yoga into their everyday lives, e.g., use of pranayama to decrease test anxiety, use of yoga nidra to help fall asleep at night, and to “take a breathing break” when in the midst of interpersonal conflicts with family members. Our intention was to give them practical “tools for life” they could use beyond the actual class time and after the intervention was completed.

These complex youth improved in all the domains we assessed. Both parents and teens reported decreased anxiety, depression, and somatization, and positive improvements in functional ability, demonstrating that the adolescents could meaningfully experience the changes and the parents could observe them. The adolescents also endorsed having decreased perceived stress, and they exhibited improved cardiovascular fitness in a 6-minute walk test. Importantly, adolescents described crucial shifts in their personal readiness to deal with the stress they experienced in their lives. This is a strong finding for a group that was perceived to be “treatment resistant” by referring health care providers. In qualitative comments recorded after each yoga class, many participants affirmed enjoying and finding benefit from the yoga practices and many of their parents commented on observed positive changes at home and in school performance.

In addition to providing a structured yoga practice, our intervention also included significant psycho-education about stress, how the autonomic nervous system functions, and how yoga practices help move the balance toward parasympathetic control rather than sympathetic control. We did not separately evaluate the impact of this education, which is not found in many community yoga classes. However, similar to school experiences, these youth seemed to respond well to a fairly structured intervention that provided rationale as well as experiential learning.

Limitations

Our study did not provide a control group. Other yoga researchers compare interventions to participants on a wait list as a control or randomized to treatment as usual [18]. However, if these interventions show an improvement in mental health and quality of life measures for those who participate in yoga, that can be due to the fact that participants are able to do something active for their own health and receive attention by being in the protocol. Given that the current state of yoga research in youth was stymied by low recruitment and retention rates, we decided it best to first create an intervention that would demonstrate both the ability to recruit and retain participants as well as show positive benefits. We demonstrated that we could recruit 8 separate groups, maintain fidelity to our curriculum, and have similar outcomes in each group. Other limitations of this study include that the participants were primarily white and female and had enough parent support for transportation to classes. In addition to the integrated and structured yoga practice, other components of this intervention that may have been beneficial were group support, active problem solving, and positive bonding with an adult leader. We were not able to separate out these components from yoga practice per sec.

Future clinical directions

Adolescents with comorbid mental and physical health disorders present a challenge to both the medical and psychiatric systems due to the complexity of their needs. Yoga, as a mindbody intervention is well suited to address their needs in both spheres. We found that medical and psychiatric practitioners were not only receptive to this approach but welcomed our help with these challenging patients. The strong results of this study, which showed yoga to help these patients, may facilitate others to integrate yoga into pediatric hospital settings.

Future research

At this point in time, we do not think it fruitful to prioritize creating control groups for yoga studies in adolescents. Rather, similar to the development of MBSR groups, now is the time to concentrate on replication of a standardized age appropriate intervention in other settings and with other types of youth. This would promote an evidence base for use of yoga in teens and ascertain for what types of problems yoga may be helpful. Other research can look at optimal dose effects, e.g., whether 8 sessions are sufficient to motivate youth to continue their yoga practice, or whether “booster sessions” may be helpful in continuing their use of these techniques to manage stress and anxiety. It may be possible with larger numbers to evaluate the benefit of added interventions such as psycho-education or group problem solving, in addition to yoga per se. We have considered whether including parents in these groups, or offering parallel yoga classes for parents, may help to maintain adherence over time. Finally, with a standardized, integrated and complex intervention that yields reliable positive effects, researchers could selectively winnow out key components of the intervention, and/or look at physiologic and cognitive mediators of the effects. This structured and age appropriate intervention may be useful for others to adopt and test these concepts.

Conclusion

This structured yoga intervention, consisting of eight weekly 150minute group sessions, was found to be acceptable and helpful to adolescents with diverse and complex medical and psychiatric symptoms. It achieved clinically and statistically significant reductions in anxiety, depression, somatization, and stress while also improving cardiovascular fitness. In addition to integrated yoga asanas, pranayama, guided relaxation and meditation, the intervention (see manual in Appendix A) sessions also included psycho-education about stress; active problem solving about barriers to practice; homework assignments; and group support. These findings provide further support for yoga as an adjunctive treatment for youth with a variety of health problems in pediatric hospital settings.

Acknowledgment

We acknowledge Children’s Hospital Colorado and the Ponzio Creative Arts Therapy Program for the resources and support to conduct this study. We acknowledge the yoga teachers who regularly volunteered to assist in the classes: Julie Schwarz, Karen Arnold, Roberta Connell, and Neila Houtchens. We gratefully acknowledge our teachers, Yogarupa Rod Stryker and Patricia Hansen. We specifically thank Rod Stryker for allowing the use of his “AM and PM Yoga” DVD, and Diana Hill, MA, Madeline Caudle, Christine McDunn and Emily Peterson, who provided valuable assistance with data collection.

References

- Ndetan H, Evans MW, Williams RD, Woolsey C, Swartz JH (2014) Use of movement therapies and relaxation techniques and management of health conditions among children. Alternative Therapies in Health & Medicine 20(4): 44-50.

- Black LI, Clarke TC, Barnes PM, Stussman BJ, Nahin RL (2015) Use of complementary health approaches among children aged 4-17 years in the United States: National Health Interview Survey, 2007-2012. National health statistics reports 78: 1-19.

- Simkin DR, Black NB (2014) Meditation and mindfulness in clinical practice. Child & Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America 23(3): 487-534.

- Ross A, Thomas S (2010) The health benefits of yoga and exercise: a review of comparison studies. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine 16(1): 3-12.

- Diorio C, Schechter T, Lee M, OSullivan C, Hesser T, et_al. (2015) A pilot study to evaluate the feasibility of individualized yoga for inpatient children receiving intensive chemotherapy. BMC Complementary & Alternative Medicine 15: 2.

- Geyer R, Lyons A, Amazeen L, Alishio L, Cooks L (2011) Feasibility study: the effect of therapeutic yoga on quality of life in children hospitalized with cancer. Pediatric Physical Therapy 23(4): 375-379.

- Evans S, Lung KC, Seidman LC, Sternlieb B, Zeltzer LK, et al. (2014) Iyengar yoga for adolescents and young adults with irritable bowel syndrome. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 59(2): 244-253.

- Evans S, Moieni M, Lung K, TsaoJ, Sternlieb B, et_al. (2013) Impact of iyengar yoga on quality of life in young women with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin J Pain 29(11): 988-997.

- Beltran M, Brown-Elhillali AN, Held AR, Ryce PC, Ofonedu ME et_al. (2016) Yoga-based Psychotherapy Groups for Boys Exposed to Trauma in Urban Settings. Alternative Therapies in Health & Medicine 22(1): 39-46.

- Nidhi R, Padmalatha V, Nagarathna R, Amritanshu R (2013) Effects of a holistic yoga program on endocrine parameters in adolescents with polycystic ovarian syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Alternative & Complementary Medicine 19(2): 153-60.

- Cramer H, Lauche R, Dobos G (2014) Characteristics of randomized controlled trials of yoga: a bibliometric analysis. BMC Complementary & Alternative Medicine 14: 328.

- Kamphaus RW, Petoskey MD, Cody AH, Rowe EW, Huberty CJ, et_al. (1999) A typology of parent rated child behavior for a national U.S. sample. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 40(4): 607-616.

- Kamphaus RW, Petoskey MD, Cody AH, Rowe EW, Huberty CJ, et_al. (1999) A typology of parent rated child behavior for a national U.S. sample. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 40(4): 607-616.

- Walker LS, Greene JW (1991) The Functional Disability Inventory: Measuring a neglected dimension of child health status. Journal of Pediatric Psychology 16(1): 39-58.

- Reynolds C, Kamphaus R (2002) The Clinician’s Guide to the Behaviour Assessment System for Children. New York, Guilford Press, USA Flanagan R (1995) A review of the Behavior Assessment System for Children (BASC): Assessment consistent with the requirements of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). Journal of School Psychology 33(2): 177-186.

- Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R (1983) A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav 24(4): 385-396.

- Prochaska JO, Velicer WF (1997) The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. Am J Health Promot 12(1): 38-48.

- Norcross JC, Krebs PM, Prochaska J O (2011) Stages of change. J Clin Psychol 67(2): 143-154.

- Miller JJ, Fletcher K, Kabat-Zinn J (1995) Three-year follow-up and clinical implications of a mindfulness meditation-based stress reduction intervention in the treatment of anxiety disorders. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 17(3): 192-200.

- Evans S, Moieni M, Lung K, TsaoJ, Sternlieb B, et_al. (2013) Impact of iyengar yoga on quality of life in young women with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin J Pain 29(11): 988-997.

- Evans S, Moieni M, Lung K, TsaoJ, Sternlieb B, et_al. (2013) Impact of iyengar yoga on quality of life in young women with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin J Pain 29(11): 988-997.

- Diorio C, Schechter T, Lee M, O’Sullivan C, Hesser T, et_al. (2015) A pilot study to evaluate the feasibility of individualized yoga for inpatient children receiving intensive chemotherapy. BMC Complementary & Alternative Medicine 15: 2.

- Evans S, Moieni M, Sternlieb B, Tsao JC, Zeltzer LK (2012) Yoga for youth in pain: the UCLA pediatric pain program model. Holist Nurs Pract 26(5): 262-271.

- Kamphaus RW, Petoskey MD, Cody AH, Rowe EW, Huberty CJ, et_al. (1999) A typology of parent rated child behavior for a national US sample. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 40(4): 607-616.

- Markil N, Whitehurst M, Jacobs PL, Zoeller RF (2012) Yoga Nidra relaxation increases heart rate variability and is unaffected by a prior bout of Hatha yoga. J Altern Complement Med 18(10): 953-953.

- Miller JJ, Fletcher K, Kabat-Zinn J (1995) Three-year follow-up and clinical implications of a mindfulness meditation-based stress reduction intervention in the treatment of anxiety disorders. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 17(3): 192-200.

- Rasekaba T, Lee AL, Naughton MT, Williams T, Holland AE (2009) The six-minute walk test: a useful metric for the cardiopulmonary patient. Intern Med J 39(8): 495-501.

- Sarubin N, Nothdurfter C, Schule C, Lieb M, Uhr M, et_al. (2014) The influence of Hatha yoga as an add-on treatment in major depression on hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal-axis activity: a randomized trial. Journal of Psychiatric Research 53: 76-83.