Comparison of Aerobic Capacity and Current Levels of Physical Activity in Yoga Practitioners and Healthy Non-Exercising Individuals

Pooja M Akhtar*, Aryaa Bhusari and Murtaza Akhtar

Maharashtra University of Health Sciences, India

Submission: August 21, 2018;Published: September 28, 2018

*Corresponding author: Pooja M Akhtar, Assistant Professor, V. S. P. M’s College of Physiotherapy, Digdoh Hills, Hingna, Nagpur-440019, India; Tel: +91-9665038090, Email: poojaakhtarvspm@gmail.com

How to cite this article: Pooja M A, Aryaa B, Murtaza A. Comparison of Aerobic Capacity and Current Levels of Physical Activity in Yoga Practitioners and Healthy Non-Exercising Individuals. J Yoga & Physio. 2018; 6(3): 555686. DOI:10.19080/JYP.2018.06.555686

Abstract

Background: The effects of Yoga to improve the cardio-respiratory endurance have demonstrated mixed results and is not considered as an aerobic activity by many. Young healthy individuals lack awareness about the traditional mode of inexpensive workout in the form of Yoga to maintain good health. They perceive themselves to be physically fit or tend to indulge into various expensive fitness programs. Thus, the present work was undertaken with an aim to study and compare the Aerobic capacity by indirect measurement (VO2 max) and current levels of Physical activity in yoga practitioners and healthy non-exercising individuals.

Methods and materials: It was an Observational Cross-sectional Study. Thirty yoga practitioners and thirty healthy non-exercising subjects underwent Queen’s step test to derive VO2max. The subjects were administered short International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) to record current levels of physical activity of current week. Comparison of VO2max. max values and IPAQ scores was done using parametric student’s t-test for the statistical change between the two groups.

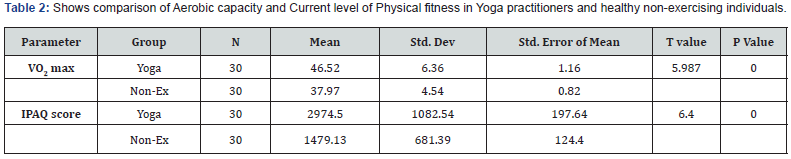

Results: The mean values of VO2max of yoga practitioners was 46.52±6.36, as compared to 37.97±4.54 in non-exercising subjects which was statistical significant (p<0.001). IPAQ scores of yoga practitioners was 2974.5±1082.5 as compared to 1479.1±681 in non-exercising healthy individuals which was statistically significant. (p<0.001)

Conclusion: Aerobic capacity (VO2 max) and IPAQ scores are higher in yoga practitioners than non-exercising healthy individuals.

Keywords: Aerobic Capacity; Queen’s step test; IPAQ, Yoga practitioners

Introduction

Aerobic capacity (VO2 max) is the maximal oxygen uptake and refers to the amount of oxygen the body is utilizes in one minute. Physical fitness depends mainly on Cardio-respiratory endurance of an individual. VO2 max (maximal oxygen uptake/ maximal aerobic power/ aerobic capacity) is widely accepted as the best measure of cardio-respiratory endurance and refers to the level of oxygen consumption beyond which no further increase in oxygen consumption occurs with further increase in the intensity of exercise and is expressed in ml/kg/minute. VO2 max is probably the best physiological indicator of a person’s capacity to continue strenous work [1]. Determination of cardiorespiratory fitness in terms of direct measurement of maximum oxygen uptake (VO2 max) is restricted within the laboratory because of its exhausting and difficult experimental protocol [2].

There are various methods to measure VO2 max, namely Treadmill test, cycle ergometry, step test as direct methods which are accurate, time consuming, expensive and need trained technicians. The indirect methods are useful and effective which include charts and formulas of Astrand and physiological (e.g.,heart rate [HR]) and subjective (e.g., rating of perceived exertion [RPE]) variables [3]. Queen’s step test is the simplest one and uses the prediction equations to calculate the VO2 max from recovery heart rate [4]. In the present study, Queen’s College step test has been used for indirectly estimating the maximum oxygen uptake to measure the aerobic capacity.

Physical activity simply means movement of the body that uses energy. Walking, gardening, climbing the stairs, playing snooker or dancing are good examples of being active. For health benefits, physical activity should be moderate or vigorous intensity. There are many tools to measure physical activity. International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) is a validated tool to measure levels of physical activity. IPAQ short form is an instrument designed primarily for population surveillance of physical activity among adults [5].

Yoga is a good exercise for maintaining optimal health as it produces consistent physiological changes with sound scientific basis leading to the upliftment of various functions of body and mind. Several reports have been made with regards to its effects on Cardiovascular, Respiratory, Metabolic, Hormonal, Neural systems and muscle strength and body composition [6]. Apart from asanas, the Physical practice of yoga, it also encompasses other components such as conscious breathing, meditation, lifestyle and diet changes, visualisation and use of sounds, among many others [7]. Since yoga is a slow-paced movement technique separated by periods of static stretching, it was not considered an aerobic activity by many. Thus, it is believed that yoga may not be beneficial to improve the cardiorespiratory endurance capacity [8]. Moreover, the effects of yoga on cardiovascular health, such as maximal oxygen consumption (VO2 max), resting heart rate and resting BP have been investigated and demonstrate mixed results [9].

Nowadays more individuals are interested in physical fitness and it depends mainly upon cardiorespiratory endurance of an individual. VO2 max is widely accepted as the best measure of cardio-respiratory endurance and it has been internationally accepted as the best parameter to evaluate Cardio-respiratory fitness [1]. Healthy non-exercising individuals perceive themselves to be physically fit and active and lack awareness as well as time to indulge into exercises and fitness programs. Yoga, being a traditional mode of workout and require no instrumentation, is a good form of exercise to practice and maintain good health. The aerobic capacity of normal, healthy, sedentary, individuals have been studied extensively using various protocols, by direct and indirect measurements; but there is scarce literature on comparative studies on Aerobic capacity, between yoga practitioners and non-exercising young healthy subjects. Thus, the present study was undertaken to compare the aerobic capacity amongst yoga practitioners and young healthy subjects.

Materials and Methods

This study was carried out at a Tertiary Care academic hospital in Central India, with an aim to study and compare the aerobic capacity (VO2 max) using Queen’s College Step test and current levels of physical activity using short form IPAQ in yoga practitioners and healthy non-exercising subjects.

An Observational Study was carried out after obtaining Ethical Clearance from Institutional Ethics Committee. Subjects were aged between 18-30 years. The Yoga practitioners were drawn from a “Yoga Life Centre” in Nagpur, practicing yoga for more than one year, atleast 4 days a week for minimum duration of 60 minutes per day. Healthy non-exercising students of V.S.P.M’s College Of Physiotherapy, who were not involved in any type of physical exercise training like gym, sports, athletics or formal aerobic training, were included. Individuals with musculoskeletal problems, spinal and abdominal surgery, pregnancy, any lower limb injuries or recent hospitalization, any history of cardiovascular, respiratory or systemic illness, presence of any neurological problems or any psychiatric illness and those who refused to participate in the study were excluded.

Yoga practitioners were performing Asanas (40 minutes), Pranayama (10 minutes) and Shavasana (10minutes). The following Asanas were practiced namely Pawanmuktasana, Naukasana, Sarvangasana, Halasana, Setubandhasana, Bhujangasana, Shalabhasana, Dhanurasana, Parvatasana, Matsyendrasana, Paschimotanasana, Hastapadasana, Padmasana and Vajrasana. Anulom –Vilom, Ujjayi, Bhramari and Bhastrika pranayama were also practiced at the centre.

Procedure: At the time of recruitment of subjects, their basic demographic data, details of their daily physical activity and yogic exercise protocol were recorded. The primary study factor was Queen’s step test in which baseline values of pulse rate and Rating of Perceived Exertion on modified Borg’s scale was recorded. Subject was made to perform Queen’s college step test by stepping up and down on 16” stepper for 3minutes. Metronome was set to cadence of 88 beats per minute for females (22 steps per minute) and 96 beats per minute for males (24 steps per minute). Posttest pulse rate was recorded for 15 seconds from 5th second after completion of the test to the 20th second. Indirect estimation of aerobic capacity (VO2max) was then calculated using the formula [10].

• Men: VO2max(m/kg/min) =111.33 - 0.42 x HR (bpm)

• Women: VO2max(m/kg/min) =65.81 – 0.1847 x HR (bpm)

Short IPAQ, our secondary study factor, was used to record current levels of physical activity of current week.

Data was analysed using EPI info software. Descriptive statistics included demographic data including age, gender and BMI. Analytical statistics included comparing VO2 max values and IPAQ scores using parametric student’s t-test for the statistical change between yoga practitioners and healthy non exercising individuals.

Results

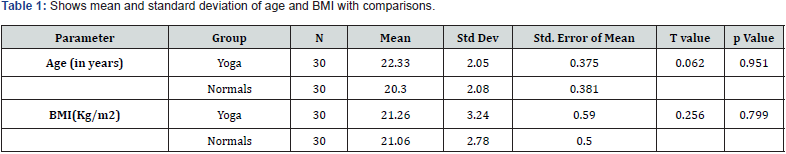

A total of 60 subjects, 30 practicing yoga and 30 non-exercising, healthy individuals were enrolled in the study. Each group had 21 females and 9 males. The mean age of the subjects for yoga practitioners was 22.33±2.05 years and for non-exercising individuals it was 22.3±2.08 years, with the range of 18-28 years. The mean BMI in yoga practitioners was 21.26±3.24 and for healthy non-exercising individual was 21.06±0.8. These two groups were comparable at baseline, as there was no statistically significant difference in gender, age and BMI (Table 1).

Inference: The two groups were comparable at baseline, as there was no statistically significant difference in age and BMI.

Inference: These statistical findings are suggestive of better aerobic capacity and better current level of Physical activity score in Yoga practitioners as compared with healthy non-exercising subjects.

On comparison, the aerobic capacity as measured using the formula for estimation of VO2 max was 46.52±6.36 in Yoga practitioners and in normal non-exercising individuals it was 37.97±4.54, the p value being < 0.001(Statistically significant). Likewise, the physical activity as measured by the IPAQ scores in Yoga practitioner was 2974.5±1082.5 and in normal nonexercising subjects it was 1479.1±681.4, the p value was <0.001 (Table 2).

These statistical findings are suggestive of better aerobic capacity and better current level of Physical activity score in Yoga practitioners as compared with healthy non-exercising subjects.

Discussion

Yoga is an ancient Indian practice first described in Vedic scriptures around 2500 BC which utilizes mental and physical exercises to attain the union of individual self with the infinite [11]. It is designed to bring balance and health to the physical, mental, emotional and spiritual dimensions of the individuals [12]. Studies have shown that yoga practice can lead to improvements in the hand grip strength, muscular endurance, flexibility and maximal oxygen uptake. In addition decrease in the percentage body fat and increase in the FVC and FEV1 have also been observed. Cardiorespiratory endurance in yoga individuals have been estimated from the Astrand Rhyming or Harvard step test [11], however data on comparison of aerobic capacity of yoga versus normal individuals is sparse.

In the present study, Yoga practitioners had higher aerobic capacity as measured by indirect method i.e. VO2 max, than healthy non-exercising subjects. These results are quite consistent with the reports of Balasubramanian et al. [13] which stated that yogic practices improve physical performance in terms of aerobic performance and cardiovascular endurance.

A study showed that the group practicing Yoga in Daily Life system had better aerobic performance than controls performing other aerobic physical activity for the same amount of time per week [14]. Thus, it may be concluded that in spite of low energy expenditure during yoga sessions, yoga has a positive effect on individuals’ aerobic performance. The results are consistent with data from Chen et al. [15] who reported a positive influence of Silver Yoga exercises on physical fitness (e.g., body composition, cardiovascular-respiratory functions or body flexibility).

Our results are in line with the study of Vinayak P Doijad [1] which indicated that the experimental group, namely yogasana practice group had significantly improved VO2 max, when compared to the control group.

Improved VO2 max after yogic exercises could be due to:

i. Increase in Oxygen Consumption by the muscles, which in turn suggest increase in muscle blood flow. This may be due to a generalized decrease in vascular tone resulting from stimulation of parasympathetic activity during Yogic Training.

ii. Conversion of some of the Fast Twitch muscle fibers into Slow Twitch muscle fibers during yogic training. Slow twitch fibers have high aerobic power.

iii. Yoga postures (asanas) involve isometric contraction which is known to increase skeletal muscle strength.

iv. Greater involvement of active muscle mass from different parts of the body [1].

The short form of IPAQ was interviewer administered questionnaire which provides a comparable scoring method for the IPAQ long form. It is an instrument designed primarily for the population surveillance of the physical activity among adults. It has been developed and tested for use in the age range of 15- 69 years. IPAQ assess physical activity across a comprehensive set of domains including leisure time physical activity, domestic and gardening activities, work related physical activity and transfer related physical activity. The IPAQ short form asks about three specific types of activity undertaken in the four domains introduced above. The specific types of activities that are assessed are walking, moderate intensity activities and high intensity activities [5].

Improved IPAQ scores in the yoga persons were observed than the non-exercising individuals as yogic techniques are known to improve one’s overall performance and work capacity [16]. Physical fitness not only refers to muscular strength and flexibility but also cardiorespiratory fitness [17]. In adults, low physical fitness (mainly cardiorespiratory fitness) seems to be a stronger predictor of both cardiovascular and all-cause mortality than any other well-established risk factors [18].

Sharma et al. [19] conducted a prospective controlled study to explore the short-term impact of a comprehensive but brief lifestyle intervention based on yoga, on subjective wellbeing in normal and diseased subjects and reported significant improvement in the subjective well-being scores of 77 subjects within a period of 10 days as compared to controls. Therefore, even a brief intervention can make an appreciable contribution to primary prevention as well as management of lifestyle diseases. In addition, research on the practice of yoga – a non-competitive, physical exercise (asana) combined with breathing (pranayama) and meditation techniques [20]– indicates that practicing yoga is associated with improved psychological well-being [21] and positive self-esteem [22]. This suggests that performing yoga postures may increase bodily energetic resources and the subjective sense of energy, and positively affects self-views [23].

Physical exercises and the physical components of yoga practices have several similarities, but also important differences. Evidence suggests that yoga interventions appear to be equal and/ or superior to exercise in most outcome measures. Emphasis on breath regulation, mindfulness during practice, and importance given to maintenance of postures are some of the elements which differentiate yoga practices from physical exercises [24].

The limitation of the present study was inability to ascertain and quantify the yogic compliance, however in situation of beneficial effect of yoga exercises demonstrated by present study, it is of no big consequence. No formal sample size calculation was done as present study was an observational hypothesis generating endeavor. No formal calculation of power of study was carried out. IPAQ scores has an inherent weakness of recall bias which cannot be rectified.

With the statistically positive results of yogic exercise demonstrated by the present study, it is advisable to have a methodologically sound study for hypothesis testing to be carried out as future direction of research to obtain better grade of evidence. Thus, we would like to appeal to the present youth to adopt Yoga as a part of their fast-pacing lifestyle to gain benefits not only in Flexibility and muscle strength but also improvement in Cardio-vascular fitness.

Conclusion

Yoga practicing individuals has better aerobic capacity as measured by VO2 max calculation and better levels of physical activity scores as recorded by IPAQ short form.

References

- Vinayak P Doijad, Prathamesh Kamble, Anil D Surdi (2013) Effect of Yogic exercises on aerobic capacity (VO2 max). International Journal of Recent Trends in Science and Technology 6(3): 119-121.

- Bandyopadhyay A (2011) Validity of 20 meter multi-stage shuttle run test for estimation of maximum oxygen uptake in male university student. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol 55(3): 221–226.

- Nasl-Saraji J, Zeraati H, Pouryaghub G, Gheibi L (2008) Musculoskeletal Disorders study in damming construction workers by Fox equation and measurement heart rate at work. Iran Occup Health 5: 55-60.

- Chatterjee P, Banerjee AK, Debnath P, Das P, Chatterjee P (2008) A regression equation for the estimation of maximum oxygen uptake in Indian male university students. Int J Appl Sports Sci 6: 1–9.

- Guidelines for Data processing and Analysis of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ)- Short and Long Forms. November 2005.

- Rameswar Pal, Mantu Saha (2013) Role of Yogic exercise on Physical Health: A Review. Indian Journal of Applied Research 3(4): 34-36.

- Desikachar K, Bragdon L, Bossart C (2005) The Yoga of Healing: Exploring Yoga’s holistic model for health and well-being. Int J Yoga Ther 15(1): 17-39.

- Clay CC, Lloyd LK, Walker JL, Sharp KR, Pankey RB (2005) The metabolic cost of Hatha Yoga. J Strength and Cond Res 19(3): 604-610.

- Allison N Abel, Lisa K Lloyd (2012) Physiological Characteristics of long-Term Bikram Yoga Practitioners. Journal of Ex Physiology 15(5): 32-39.

- McArdle WD, Katch FI, Pechar GS, Jacobson L, Ruck S (1972) Reliability and interrelationships between maximal oxygen uptake, physical work capacity and step test scores in college women. Medical Science of Sports & Exercise 4: 182-186.

- Mark D Tran MS, Robert G Holly, Jake Lashbrook BS, Ezra A Amsterdam (2007) Effects of Hatha Yoga Practice on the Health-Related Aspects of Physical Fitness. Preventive Cardiology 4(4): 165-170.

- Pallav Sengupta (2012) Health Impacts of Yoga and Pranayama: A State-of-the-Art Review. Int J Prev Med 3(7): 444-458.

- Balasubramanian B, Pansare MS (1991) Effect of yoga on aerobic and anaerobic power of muscles. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol 35(4): 281- 282.

- Eliška Sovová, Vít Čajka, Dalibor Pastucha, Jana Malinčíková, Lenka Radová, et al. (2015) Positive effect of yoga on cardiorespiratory fitness: A pilot study. Int J Yoga 8(2): 134-138.

- Chen KM, Fan JT, Wang HH, Wu SJ, Li CH, et al. (2010) Silver yoga exercises improved physical fitness of transitional frail elders. Nurs Res 59(5): 364-370.

- Chandra AK, Sengupta P, Goswami H, Sarkar M (2013) Effects of Dietary Magnesium on Testicular Histology, Steroidogenesis, Spermatogenesis and Oxidative Stress Markers in adult rats. Ind J Exp Biol 51(1): 37-47.

- Sengupta P, Sahoo S (2011) Evaluation of Health Status of the Fishers: Prediction of Cardiovascular Fitness and Anaerobic Power. World J Life Sci Med Res 1(2): 25-30.

- Chaudhuri P, Sengupta P, Ganguli S, Halder RP (2012) Emerging Trend of Gym Practice and Its Consequence over Physical and Physiological Fitness. Biol Exer 8: 49-58.

- Sharma R, Gupta N, Bijlani RL (2008) Effect of yoga based lifestyle intervention on subjective well-being. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol 52: 123-131.

- Sengupta P (2012) Health Impacts of Yoga and Pranayama: A State-ofthe- Art Review. Int J Prev Med 3(7): 444-458.

- Shapiro D, Cline K (2004) Mood changes associated with Iyengar yoga practices: a pilot study. Int J Yoga Ther 14(1): 35-44.

- Sethi JK, Nagendra HR, Sham Ganpat T (2013) Yoga improves attention and self-esteem in underprivileged girl student. J Educ Health Promot 2: 55.

- Patil SG, Mullur LM, Khodnapur JP, Dhanakshirur GB, Aithala MR (2013) Effect of yoga on short-term heart rate variability measure as a stress index in subjunior cyclists: a pilot study. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol 57(2):153-158.

- Govindaraj R, Karmani S, Varambally S, Gangadhar BN (2016) Yoga and physical exercise - a review and comparison. Int Rev Psychiatry 28(3): 242-253.