Improving Wellness and Reducing Stress among Incarcerated Men with Mindfulness- Based Stress Reduction Programming

Nancy Wolff*

Distinguished Professor, Bloustein School of Planning and Public Policy, Rutgers University, USA

Submission: May 23, 2018;Published: June 22, 2018

*Corresponding author: Nancy Wolff, Bloustein School of Planning Public Policy, Rutgers University, Office 273, 33 Livingston Avenue, New Brunswick, New Jersey ZIP: 08901, USA, Tel: 01 848 932 2944; Email: mmcneely@ualberta.ca

How to cite this article: Nancy W. Improving Wellness and Reducing Stress among Incarcerated Men with Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction Programming. J Yoga & Physio. 2018; 5(3): 555665. DOI:10.19080/JYP.2018.05.555665

Abstract

This mixed-methods pilot study explores the effectiveness of a corrections-adapted mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) program for incarcerated men who had been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress (PTSD) and completed an integrated trauma and addiction treatment program but still presented with above average levels of prison-related stress. Our inquiry explored whether a MBSR program (16, 2-hour sessions) would lower prison-related stress, PTSD-related symptoms, and symptom severity, while improving self-esteem, coping, and self-efficacy. The study included 58 men incarcerated in a maximum security prison. Participants were interviewed at baseline, end of program, and at three- and six-month post-completion, with a focus group at the conclusion of the program. An intent-to-treat analysis was conducted; change scores were computed between pre- and post-program averages for the primary, secondary, and mindfulness measures. We found that incarcerated men in our sample (a) were willing to participate in the program that included meditation and yoga; (b) were receptive to and successful at practicing the principles of mindfulness; and (c) experienced reduced PTSD symptoms and improvements in self-esteem, proactive coping skills, self-efficacy, and mental health. In general, these benefits endured over the six-month follow up period. These findings are consistent with the perspectives shared during the focus groups. In general, participants found the program helpful in reducing and managing their stress, increasing their sense of control and empowerment, building their trust in themselves and others, and expanding their sense of mastery.

Keywords: Mindfulness; MBSR; Incarcerated men; Prisons

Introduction

Everyday life is stressful particularly when those days are spent detained behind bars. Prison environments are typically characterized by deprivation, dehumanization, violence, and rigidity [1]. They are also known for their uncertainty; violence could break out at any moment but also rules of order are often subjectively interpreted by staff, creating confusion about what is allowed, by whom, and when. These types of living conditions create stress and combine with the natural stress associated with being deprived of liberty and separated from people who personally care. Researchers are increasingly exploring the harmful effects of chronic stressors on health and psychological well-being. Elliot and Eisdorfer define chronic stressors as experiences that “usually pervade a person’s life, forcing him or her to restructure his or her identity or social roles” and are often characterized by instability, where “the person either does not know whether or when the challenge will end or can be certain that it will never end” [2]. Chronically activating the body’s stress-response system overwhelms the body with stress hormones, which taxes the human immune system, [3] and increases the likelihood of adverse problems, such as anxiety, depression, digestive problems, heart disease, sleeping disorders, and memory and concentration problems [4].

Prison is a chronic stressor. Not feeling safe where you live triggers hypervigilance and hyper-responsiveness [5]. Chronic stress also interacts with two factors associated with maladaptive coping: self-regulation -the ability to consciously moderate one’s behavior and emotions -and negative affect states -including anxiety, anger, and depression [6]. Being able to regulate thoughts, emotions, and actions translates into an ability to respond more judiciously to people, places, and things. Research, however, has found that offenders have difficulties regulating their emotions and behaviors [7], which is characterized as a dynamic, criminogenic need. In general, better self-regulation skills yield self-control abilities that more effectively manage impulsivity, goal attainment, decision making, and negative affect states. Chronic stressors, however, stimulate chemical processes within the body that promote impulse reactions and negative affectivity.

Building abilities to better self-regulate and manage stress is, therefore, likely to benefit people living in prison. While there are many interventions developed to manage stress (e.g., muscle relaxation, autogenic training and biofeedback, mindfulness-based stress reduction) [8], the one that has the strongest evidence base is mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) [9]. Mindfulness, as defined by Jon Kabat-Zinn [4], the founder of MBSR, is the practice of paying attention to the present moment without judgment. As a practice, it involves building attentional awareness through various forms of meditation and practicing attitudes that support emotional regulation, cognitive reprocessing, tolerance, and compassion for self and others [10,11]. The MBSR program, developed at the University of Massachusetts (UMASS), has been completed by over 24,000 people and is now offered at more than 300 health care settings.

The logic of MBSR using a prison-based example is as follows: prison chaos/uncertainty (the stimulus) creates stress; the resulting stress (e.g., worry, anger, anxiety) can directly and indirectly trigger (or exacerbate) health or behavioral health problems and lower overall well-being. Between the stimulus and reaction is a choice point: the person can choose to react or not. Being mindful of the moment and decisional space, the individual could choose to react (impulsively/reflexively) or respond (non-judgmentally/thoughtfully). Through the practice of mindfulness, individuals become aware of moments of choice, pause for breath, and practice responding with equanimity and balance. Learning to stop and take a breath or two and then respond with acceptance and non-judgment to stimuli is a central feature of mindfulness. In this sense, MBSR is a personempowering intervention.

Based on community samples, researchers have found that interventions with features of mindfulness improve symptoms related to chronic stress, anxiety, depression, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder [12]. Improved affect states, coping abilities, and states of mind, as well as less emotional distress have been found in meta-reviews of MBSR [12-14]. People in a more mindful state appear to be better able to regulate their responses to stress because of their “greater emotional awareness, understanding, acceptance, and ability to repair unpleasant mood states” [14]. Most noteworthy is the advancing neurological research of mindfulness that shows that mindfulness increases the density of gray matter in areas of the brain associated with depression and anxiety and the regulation of emotion and enhanced learning [15-18].

While in its infancy, corrections-based research on mindfulness is growing. Small but significant improvements in psychological well-being and behavioral functioning among those who completed yoga or meditation programs was reported in a meta-analysis of prison-based yoga and mindfulness meditation programs. Marginally larger improvements in behavioral functioning were found for programs with longer durations [19]. One large scale study (n=1953 adults, six minimum and medium prisons, 113 MBSR groups), conducted between 1992 and 1996, found that MBSR participants showed significant improvements in hostility, self-esteem, and mood disturbance, with no similar changes for the ad hoc control group [20]. These findings parallel those of other studies of meditationbased interventions conducted in correctional settings showing significant improvements in a number of criminogenic variables including negative effect, substance use, anger, and self-esteem [6,8,21,22]. Behavioral change resulting from intervention often diminishes following the withdrawal of the intervention [23].

Our study adds to this literature by focusing on a group of incarcerated men diagnosed with post-traumatic stress (PTSD) who had completed an integrated trauma and addiction treatment program but still presented with above average levels of prison-related stress. As a pilot study, our inquiry explored whether a MBSR program modified for a prison setting would be effective in lowering prison-related stress, PTSD-related symptoms, and symptom severity, while improving self-esteem, coping, and self-efficacy.

Methods

Participants

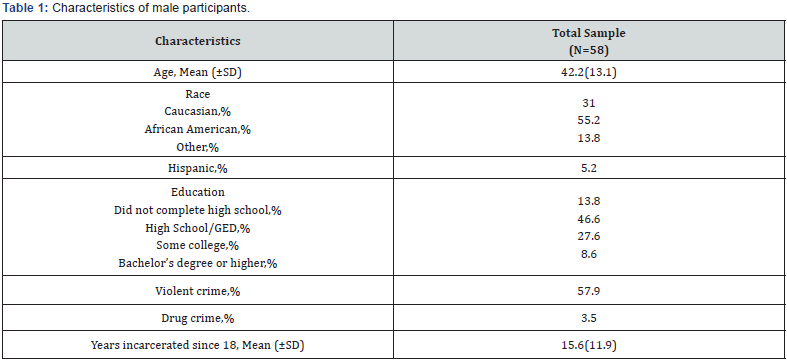

Participants were drawn from a group of incarcerated men who screened positive for PTSD and substance abuse disorder and completed an integrated treatment intervention for PTSD and addiction disorders as part of a randomized controlled trial implemented at a high security prison operated by the Pennsylvania Department of Corrections between February 2012 to January 2014. Men who met the inclusion criteria completed a baseline prison stress questionnaire (adapted from Maitland & Sluder [24]) and were invited to participate in the mindfulness part of the study if they scored above average on the screen. Of the 75 invited to participate, 58 consented to be assigned to a MBSR group. A total of six groups, varying in size from 9 to 10, were facilitated by two protocol-trained facilitators over a six-month period. Table 1 shows the characteristics of the participants. The majority of participants were African-American (55.2%), had completed high school or its equivalence or some college (82.6%), and committed a violent crime (57.9%). On average, participants were 42 years of age (ranging from 22 to 74) and had been incarcerated for nearly 16 years (ranging from 2 to 44 years).

Intervention

MBSR is a group-based intervention delivered over eight weeks and includes: bi-weekly sessions of two hours; guided mindfulness exercises, yoga exercises; self-practice; and a daylong retreat [4,25,26]. The MBSR intervention was adapted, in collaboration with the Center for Mindfulness as UMASS, for correctional populations.

Procedure

Self-report data were collected from participants at four points: at baseline, immediately after completing the intervention, three-months follow-up, and six-months follow-up. A questionnaire with multiple measures was administered by computer (except the CAPS, which was clinician-administered). Information was also collected on age, race, ethnicity, education, type of crime, and years incarcerated. Focus groups were conducted by the research staff at the end of the intervention. The focus group protocol included six questions about participation, expectations, preferences, challenges, and recommendations. Focus groups were audio-taped and the tapes were transcribed by an independent service. Participants signed consent forms to participate in the study and were not compensated. All protocols were approved by the appropriate research committees and institutional review boards.

Three primary outcomes were used to measure effectiveness. They were: the PTSD Checklist for Civilians (PCL-C) [27], the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS) [28], and the Global Severity Index (GSI) of the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI), a measure of psychological symptom severity [29]. Secondary outcomes were measured using the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (SES) [30], Proactive Coping Inventory (PCI) [31], and Generalized Perceived Self-Efficacy (GPEF) [32]. All measures have strong psychometric properties and were scored using standard procedures.

To measure the experience and skill development of mindfulness, several measures were used, including the perceived stress scale (PSS), a 10-item, self-report measure of stress perception [33]; Kentucky Inventory of Mindfulness Skills (KIMS), a 39-item self-report measure of observing, describing, act with awareness, and accept without judgment [34]; the Freiburg Mindfulness Inventory, a 14-item, self-report single construct measure of mindfulness [35]; the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS), a 15-item, self-report measure of awareness and attention [36]; Self-Compassion Scale (SCS), a 26-item, self-report measure of self compassion [37]; Self-Other Four Immeasurables (SOFI), a 16-items, self-report measure of loving-kindness, compassion, joy, and acceptance toward both self and others [38]; and Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS), a 42-item, self-report measure of depression, anxiety, and tension/stress [39,40].

Statistical Analysis

An intent-to-treat analysis was conducted. Change scores were computed between pre- and post-program averages for the primary, secondary, and mindfulness measures using paired t-test or McNemar test. Proportions and means (and standard deviations) were computed to describe demographic and background characteristics. The significance level used to test differences was 0.5. All statistical analyses were performed using Proc means, freq, and t test in SAS 9.2.

Quantitative Results

Changes pre- and post-treatment for the primary and secondary outcomes are shown in Table 2. At baseline, the average prison stress score for the 58 participants was 136.8 out of maximum score 205 (67% of the total). Prison stress significantly decreased to its lowest average level of 120.7 at the end of treatment, based on those who completed the mindfulness program, increasing slightly at three- and six-month followup, although these mean levels were still significantly lower than the prison stress level at baseline. There were significant improvements for all primary and secondary outcomes (except the GPEF, significant improvement was only at three-month follow-up) compared to the baseline scores. Most noteworthy is the 10 to 13 point decline in the mean score on the CAPS (PTSD severity) (a 10-point decline is clinically significant [40]). There was also a significant decline in the psychological symptom severity (GSI) post-treatment and at three- and six-month followup, compared to the baseline level. Significant improvements were also found in the mean scores post-treatment and followup for self-esteem (SES, except for three-month follow-up), proactive coping skills (PCI), and self-efficacy (GPEF, 3-month follow-up only).

*p<0.05; **p<0.01 comparing T1, T3 and T6 results to baseline using paired t-test or McNemar test.

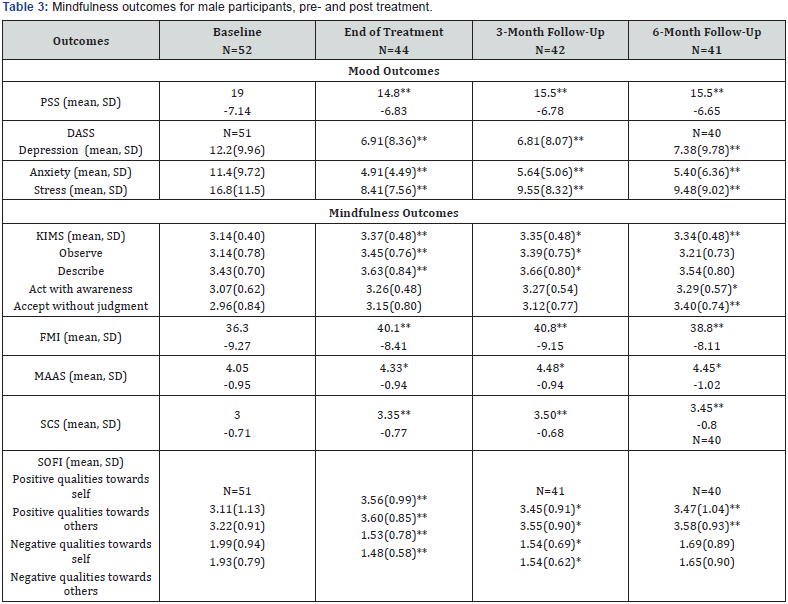

The impact of participation in MBSR on mood and mindfulness practice is shown in Table 3. The mean scores for all of these measures showed significant improvement posttreatment compared to baseline levels and these improvements persisted in the three and six months after completing the program (with a few notable exceptions for SOFI constructs at six-month follow-up). In terms of mood measures, there was a significant and persistent improvement in perceived stress (declined by an average of 3.5 to 4 points), depression (declined by an average 4 to 5 points), anxiety (declined by an average of 6 points), and stress (declined by an average of 7 to 8 points).

*p<0.05; **p<0.01 comparing T1, T3 and T6 results to baseline using paired t-test.

In terms of the mindfulness measures, mindfulness increased significantly in terms of practicing mindfulness skills (KIMS), mindfulness (FMI), mindful attention and awareness (MAAS), and self-compassion (SCS). The SOFI measure of qualities of engagement with self and others also significantly improved in terms of positive qualities towards self or other (inclusive of being friendly, joyful, accepting, and compassionate to self or other) and negative qualities of self or other (inclusive of being mean, hateful, angry, or cruel to self or other)(SOFI), although the gains with respect to negative qualities toward self and others diminishes by the six-month follow-up and the difference compared to the baseline level lost significance. Similarly, the practice of mindfulness skills (KIMS) showed a significant improvement in observing and describing at the end of treatment and three-months but not at six-months, while a significant improvement in acting with awareness and accepting without judgement is found at six-month follow-up only.

Qualitative Results

Four central themes, described below, emerged from the focus groups that directed the participants to reflect about their experience with the MBSR program. These themes were: trust, safety, sensory attunement, and liberation.

Trust

The participants frequently talked about how they trusted each other and the facilitator and how this feeling was atypical in a prison setting. People in prison are consistently on alert because danger and unpredictably are ever-present. For them to close their eyes in a group and focus internally requires trust. They must trust the people in the room to be able to practice meditation and stretching yoga.

“For me to sit there and be able to totally meditate in the zone, there has to be trust around me, because for me, I just don’t like to trust people.”

“These dudes were all serious about coming here and doing this, you know, and seeing everybody be real about it… like when you asked “how’s your practice going?” [and] guys would just say “oh, it’s awful”… it was like really easy to put trust in the guys … there was a lot of realism.”

“I’m always uncomfortable whenever I meet a group of people that are essentially strangers to me, and I know that I’m going to have to let my guard down … once the group came down to seven or eight, you knew all the guys left were rock solid, you relax…”

“The enthusiasm .. of the facilitators, it is something that we don’t have … you interject trust … I believe this worked so well … because trust was the main issue.”

“We know we can trust [facilitator] … [he is] very skilled, very personal … he became a part of this.”

Safety

Related to trust is safety. It is uncommon to feel safe in a prison if you are a resident. If you have a single cell, safety happens when the door is locked; keeping others out and you in. To feel safe in the presence of other residents is not expected especially when you are experimenting with something foreign. In the MBSR program, the person might not get the raisin meditation or the see the answer to the nine-dot exercise or be able to do the yoga pose. So many vulnerable moments that might make the person feel different or weak or stupid. Being laughed at or ridiculed often triggers self-loathing and anger, which discourages people from group-based experimentation. The men in the MBSR groups reported feeling comfortable and safe.

“I was able to relax and to be open enough for whatever was going to happen.”

“I was hoping that when I got here for mindfulness class that I would have a safe environment so I would be able to feel and acknowledge certain things… cause you don’t have that environment everywhere in this prison … I felt like I belong here.”

“All the time in the groups you just let it go, just be trusting … I felt safe.”

“The bond that was built with these men in this room … they made it feel comfortable for me to open up a little bit … some days I didn’t feel like making it, and when I did, my energy changed once I got amongst these men.”

Sensory attunement

Many of the participants talked about how they were more attuned with their thoughts, body, and mind because of their participation in the program, and they reported that this attunement helped them to manage life with less stress.

“Mindfulness has helped me be a lot less stressed. I’m more empathetic toward people, but I also care about major things a whole lot less than I used to. I don’t take things seriously.”

“I very rarely get to the point where I red line on stress anymore. I’m able to somewhat more easily communicate when there’s a problem.”

“I was actually able to start calming me down with walking meditation … when I’m out in the yard … I was able to walk and just calm down … basically zone out and relax.”

“I kinda stay tensed all the time … tense inside … the breathing exercises and things really started teaching me how to relax. I’m not used to relaxing.. I realized that it’s really helped me to relax a bit.”

“I left the class [and] felt spiritually calm. Because of this environment [prison] where every day you feel kind of spiritually dull because of the situation that’s all around. It feels like a dark environment … [but] when I left here I just felt like I wanted to smile… I just felt like I was alive.”

“Being in this program really helped me … I started thinking how to slow down instead of just racing into things.”

“I have bad anxiety … [and] the first reaction is my hands shake but I breathe through my nose, just practice breathing right there in that moment, just close my eyes just for a second and do that, and I open my eyes and I’m a lot calmer.”

Liberation

Some of the respondents reported that the skills of the MBSR program allowed them to feel free, to feel their bodies, to experience life less burdened, and to let thing go so that they could enjoy the present moment.

“Everybody’s worried and stressing as it is. We all have so much on the table in our personal lives, and then with the bull crap that’s going on within the walls. So for an hour or so to sit there and actually let stuff just go is good.”

“We’re doing meditation and yoga to relieve any other stress. It’s better than anything else that exists, I think.”

“I love yoga … it frees my body. [W] when you start doing yoga that’s when you realize how much your body has been so tense and tight and like you feel like somebody’s restraining you … yoga feels like [it] frees your body, your body feels like it moves more naturally, your balance is better… I like that it frees my body.”

‘I didn’t expect to feel free wearing browns [prison uniform].”

Conclusion

This small-scale study of a corrections-adapted MBSR program suggests that some incarcerated men housed in a maximum security prison with known PTSD-related symptoms and above average levels of prison stress (a) are willing to participate in the program that includes meditation and yoga; (b) are receptive to practicing the principles of mindfulness; and (c) benefit from the program in terms of reduced PTSD symptomology and improvements in self-esteem, proactive coping skills, self-efficacy, and mental health. These benefits appear to endure over the six-month follow up period, although negative qualities associated with self and others receded to levels not significantly different from baseline by the six-month follow-up. These findings are consistent with the perspectives shared during the focus groups. In general, participants found the program helpful in reducing and managing their stress, increasing their sense of control and empowerment, building their trust in themselves and others, and expanding their sense of mastery. Our findings are consistent with the meta-analysis of prison-based yoga and mindfulness meditation, which found marginal improvements in psychological wellness and behavioral functioning [19]. Given that some of the benefits gain with the intervention begin to diminish with time, a booster session (e.g., a Sangha) may help to support the practice of mindfulness and preserve the trust alliance established as part of the group intervention [23].

Limitations

This research was designed as a pilot study. As such, the sample size was small and it lacked a control group, both of which are study limitations. Another possible confounder is that participants rolled over from an integrated trauma-addiction treatment intervention, and had favorable opinions of the principal investigator and the group facilitators. These favorable pre-dispositions may have contributed to the men’s willingness to participate in the study and their positive receptivity to the MBSR principles. Social desirability bias, therefore, may be nontrivial.

Future Research Direction

Stress levels are extremely high in prison environments and this study suggests that MBSR has the possibility of helping incarcerated men manage their stress in healthier ways. A larger scale study is needed to produce findings that are generalizable. More qualitative research is needed to identify ways to build receptivity among incarcerated men for meditation and yoga, as well as support the dispositional changes after the program ends.

References

- Wolff N, Shi J (2009) Contexualization of physical and sexual assault in male prisons: Incidents and their aftermath. J Correct Health Care 15(1): 57-77.

- Elliot GR, Eisdorfer C (1982) Stress and human health: An analysis and implications of research. A study by the Institute of Medicine, National Academy of Sciences. Springer Publishing, New York, USA.

- Segerstrom SC, Miller GE (2004) Psychological stress and the human immune system: A meta-analytic study of 30 years of inquiry. Psychol Bull 130(4): 601-630.

- Kabat Zinn J (2009) Full catastrophe living. Random House, New York, NY, USA.

- Foa EB, Steketee G, Olasov Rothbaum B (1989) Behavioral/cognitive conceptualizations of post-traumatic stress disorder. Behav Ther 20(2): 155-176.

- Dafoe T, Stermac L (2013) Mindfulness meditation as an adjunct approach to treatment within the correctional system. J Offender Rehabil 52(3): 198-216.

- Stewart L, Rowe R (2000) Chapter15: Problems of self-regulation among adult offenders.

- Kristofersson GK, Kaas MJ (2013) Stress management techniques in prison setting. J Forensic Nurs 9(2): 111-119.

- Goyal M, Singh S, Sibinga EMS, Gould NF, Rowland Seymour A, et al. (2014) Meditation programs for psychological stress and well-being: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med 174(3): 357- 368.

- Kabat Zinn J (1994) Wherever you go, there you are: Mindfulness meditation in everyday life. Hyperion, New York, NY, USA.

- Kabat Zinn J (2003) Mindfulness-based interventions in context: Past, present, and future. Clin Psychol 10: 144-156.

- Grossman P, Niemann L, Schmidt S, Walach H (2004) Mindfulnessbased stress reduction and health benefits: A meta-analysis. J Psychosom Res 57(1): 35-43.

- Baer RA (2003) Mindfulness training as a clinical intervention: A conceptual and empirical review. Clin Psychol 10(2): 125-143.

- Greeson JM (2009) Mindfulness research update: 2008. Complement Health Pract Rev 14(1): 10-18.

- Kluepfel L, Ward T, Yehuda R, Dimoulas E, Smith A, et al. (2013) The evaluation of mindfulness-based stress reduction of veterans with mental health conditions. J Holist Nurs 31(4): 248-255.

- Hölzel BK, Carmody J, Vangel M, Congleton C, Yerramsetti SM, et al. (2011) Mindfulness practice leads to increases in regional brain gray matter density. Psychiatry Res 191(1): 36-43.

- Hölzel BK, Ott U, Gard T, Hempel H, Weygandt M, et al. (2008) Investigation of mindfulness meditation practitioners with voxelbased morphometry. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 3(1): 55-61.

- Singleton O, Holzel B, Vangel M, Brach N, Carmody J, et al. (2014) Change in brainstem gray matter concentration following a mindfulness-based intervention is correlated with improvement in psychological wellbeing. Front Hum Neurosci 8: 33.

- Auty KM, Cope A, Liebling A (2017) A systematic review and metaanalysis of yoga and mindfulness meditation in prison: Effects on psychological well-being and behavioural functioning. Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol 61(6): 689-710.

- Samuelson M, Carmody J, Kabat Zinn J, Bratt MA (2007) Mindfulnessbased stress reduction in Massachusetts correctional facilities. Prison J 87: 254-268.

- Shonin E, Van Gordon W, Slade K, Griffiths M (2013) Mindfulness and other Buddhist-derived interventions in correctional settings. Aggress Violent Behav 18(3): 365-372.

- Himelstein S (2011) Meditation research: The state of the art in correctional settings. Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol 55(4): 646- 661.

- Whisman M (1990) The efficacy of booster maintenance sessions in behavior therapy: Review and methodological critique. Clin Psychol Rev 10(2): 155-170.

- Maitland AS, Sluder RD (1998) Victimization and youthful prison inmates: An empirical analysis. Prison J 78(1): 55-73.

- Kabat Zinn J, Lipworth L, Burney R (1992) The clinical use of mindfulness meditation for the self-regulation of chronic pain. Am J Psychiatry 149: 936-943.

- Stahl B, Goldstein E (2010) A mindfulness-based stress reduction workbook. New Harbinger Publications, Oakland, CA, USA.

- Wilkins KD, Lang AJ, Norman SB (2011) Synthesis of the psychometric properties of the PTSD checklist (PCL) military, civilian, and specific versions. Depress Anxiety 28(7): 596-606.

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW (2002) Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV-TR axis I disorders, research version, patient edition with psychotic screen. Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute, New York, NY, USA.

- Derogatis LR (1993) A brief form of the SCL-90-R: A self-report symptom inventory designed to measure psychological stress: Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI). National Computer Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA.

- Crandal R (1973) The measurement of self-esteem and related constructs. In: Robinson JP, Shaver PR (Eds.), Measures of social psychological attitudes (Revised Edition). Institute for Social Research, Ann Arbor, MI, USA, pp. 80-82.

- Greenglass E, Schwarzer R (1998) The proactive coping inventory (PCI). In: Schwarzer R (Ed.), Advances in health psychology research (CD: ROM). Institute for Arbeits, Organizations and Gesundheitspsychologie, Free University of Berlin, Berlin, Germany.

- Schwarzer R, Jerusalem M (1995) Generalized self-efficacy scale. In: Weinman J, Wright S, Johnston M (Eds.), Measures in health psychology: A user’s portfolio. Causal and control beliefs. NFER-NELSON, Windsor, UK, pp. 35-37.

- Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R (1983) A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav 24(4): 385-396.

- Baer RA, Smith GT, Allen KB (2004) Assessment of mindfulness by self-report: The Kentucky inventory of mindfulness skills. Assessment 11(3): 191-206.

- Walach H, Buchheld N, Buttenmüller V, Kleinknecht N, Schmidt S (2006) Measuring mindfulness: the freiburg mindfulness inventory (FMI). Pers Indiv Differ 40(8): 1543-1555.

- Brown KW, Ryan RM (2003) The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol 84(4): 822- 848.

- Neff KD (2003) Development and validation of a scale to measure selfcompassion. Self and Identity 2: 223-250.

- Kraus S, Sears S (2009) Measuring the immeasurables: Development and initial validation of the self-other four immeasurables (SOFI) scale based on Buddhist teachings on loving kindness, compassion, joy, and equanimity. Social Indicators Research 92: 169.

- Lovibond PF, Lovibond SH (1995) The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the depression anxiety stress scales (DASS) with the Beck depression and anxiety inventories. Behav Res Ther 33(3): 335-342.

- Schnurr PP, Friedman MJ, Foy DW, Shea MT, Hsieh FY, et al. (2003) Randomized trial of trauma-focused group therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder: Results from a department of veterans affairs cooperative study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 60(5): 481-499.