The Case of Wudang Yoga

Rene Goris*

IOCV Daoland Healthcare Education, Netherlands

Submission: January 20, 2018;Published: June 22, 2018

*Corresponding author: Rene Goris, IOCV Daoland Healthcare Education, NL 2015, Netherlands, Email: renegoris1@gmail.com

How to cite this article: Rene G. The Case of Wudang Yoga. J Yoga & Physio. 2018; 5(3): 555662. DOI:10.19080/JYP.2018.05.555662

Abstract

When people speak of yoga they usually talk about its origins, the Europanized versions of yoga, or in Asia the elegant forms of China’s Fashion Yoga craze copied from India and the west. Much less known is the almost 2000 years of yoga development in China itself and the massive influence it has on spiritual practices of East Asia at large. In this paper the case of Wudang Yoga is measured against some of the physical benefits with the use of questionnaires.

Brief Introduction into the History of Yoga

There is a large variety how westerners translate yoga. But Yoga shares origin with the word Dhyani, from Dhyani Buddha. Dhyani means something like contemplation or meditation. In general Buddhism and Yogism are considered to be related more than yoga and Hinduism due to the emphasis on meditation as a way forward in personal and spiritual development1. Meditation gains rapid popularization in modern society as a means to deal with psychological conflict. Within the context of Daoist and Buddhist martial arts meditation is also a tool to deal with behavior and performance in doing things in a more concentrated way. As such yogic meditation can have a great development for itself in the last context that is hardly tapped into, and could find itself eventually in the heart of future educational programs for the aged as well as the young. For now, yoga finds mostly interest as a way of doing alternatives for regular sports or as a way to deal with stress.

The origins of yoga in Indian sources are found in the writings of Patanjali2 and Svatmarama3. In both thinkers Yoga is primarily described as meditation. Patanjali described only sitting meditation and like Vipassana in pure Buddhist practice Svatmarama added more extensive practices to deepen meditation in the form of ten new postures. The core of svatmarama’s thought is that yoga has two intertwined aspects, namely of hatha-corporeality, and raja-(royal) attitude as means for achieving goals in yoga. Svatmarama determined that if they do not come together it cannot be yoga. Combined physical and spiritual practice was part of Shang and Zhou thought, but emphasis was more on health and power than on mental of spiritual achievement in the Buddhist yogic sense. The practice was called Daoyin, guidance skill, where internal forces and substances were redistributed through movement, breath etc. From the formation period there is too little known to equate daoyin with yoga4. Yoga was through the text and practice of Yoga Pradipika of Svatmarama coming to China as part of Buddhist practice. As such is gradually became well known in both Buddhism and Daoism as Daoism absorbed more and more Buddhist influences during the Han to the Song dynasties. It is my idea that Svatmarama’s text also helped birth the transformation of waidan alchemy to neidan alchemy5. Waidan alchemy seeks to achieve immortality through medical intervention and neidan alchemy seeks to achieve immortality through personal internalized effort. The suggestion of neidan alchemy is that behavior alters personal development, including body chemistry, which is for now confirmed in rna research based epigenetic science6.

The influence on Daoism is most clearly seen in the changing use and purpose of daoyin in neidan practices. The goal of achieving health was not abandoned, but it certainly confluenced with spiritual needs. The mental state of a person gained dominance as a cause of health. This culminated in f.i. a little known practice as part of Daoist taiji gongfu. Taiji gongfu is the means to achieve immortality through physical and mental practice, build up in 4 stages:

1) Zhuji, building practice place;

2) Practice Jing-coherence and flower qi-perfection;

3) Practice qi to flower shen-awareness;

4) Shen returning to weakness. The weakness is that the cessation of resistance of the mind to live properly. This article is too short to deal with what properly means in this context.

Wudang yoga, or wudang daoyin, is a set of meditative practices in which movements and postures combine with breathing patterns to generate the right foundations for alchemical success. Many of the moves seem to be following a similar pattern of shaking, turning and twisting as in modern laboratories. In the sideline it is claimed to help practitioners to achieve health mental stability, concentrational powers etc. it also is a foundation of successful martial development in taiji boxing.

The influence of western science and commercial use has gradually muddied the perspectives on the values of such practices as Wudang yoga and how their original format can be of use in health and personhood development in modern societies. Science usually only has a partial understanding of the practices she investigates, notwithstanding its proper investigative intentions to clarify phenomena it doesn’t yet understand. This is the sad story of modernization and innovation that we see repeated in the research of oriental practices such as yoga, meditation, acupuncture, herbal medicine: although it clarifies aspects, in general it ends the intended use of a skill and replaces it with a skill that falls outside of the scope of what it needs to do as part of its original cultural modus operandi.

As part of my research I attempted to show validity of practices like wudang yoga in a modern setting but with use of pre-modern conceptualization, and thus the exclusion of modern ideas like air as a gas, qi as energy, jing as essence, shen as spirit, the use of the idea of a soul, political, scientific and commercial needs, etc. These concepts originally were not part of the quietist lifestyle and spiritual of religious needs of daoists. The research and testing I commenced over a period of ten years and 200 students in different levels did focus on observing

a. The practice of body and attitude in wudang yoga

b. The use of breath in wudang yoga

c. The stages of development in breath practice

d. The stages of development in mental practice

In this paper the emphasis is on the speed of development of physical benefits.

Foot Note

1Joseph SA (2004) Yoga in modern India; The Body Between Science and Philosophy. Princeton University Press, USA.

2Barbara SM (1996) Yoga: discipline of freedom; The Yoga Sutra Attributed to Patanjali. University of California Press, USA.

3Swami S (2004) Hatha Yoga Pradipika in Sanskrit and English

4Yuzeng L, Terri M (1999) Wudang Qigong: China’s Wudang Mountain Daoist Breath. Shandong University Press, China.

5Sivin N (1968) Chinese Alchemy: Preliminary Studies. Harvard University Press, USA.

6Plomin R (1994) Sage series on individual differences and development. Genetics and experience: The interplay between nature and nurture. Thousand Oaks, Sage Publications, USA.

Target Group

From 200 participants 120 took part in a short course track through a Group on commercial offer of 10 sessions. I measured in only 8 groups of maximum 20 participants in 2014 en 2015, and merged the results with participants that practiced for a longer time for comparison. The nature of the group on action might have been due to the reason why people did not progress to a next stage due to increasing costs of participation. The entire project was done without subsidizement so no high discounts could be offered. From the remaining part of 80 participants included in the program only 15 followed up all the 4 years they were followed and were followed an additional year through self-practice. The research outcomes determined long and short term benefits, motivational issues, language issues in teaching and instructing, technical aspects of yoga, an d future research requirements and goals.

Questionnaire

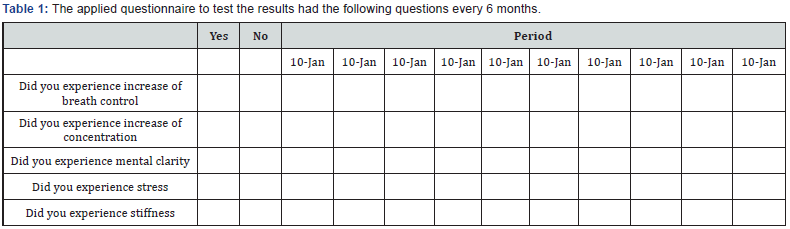

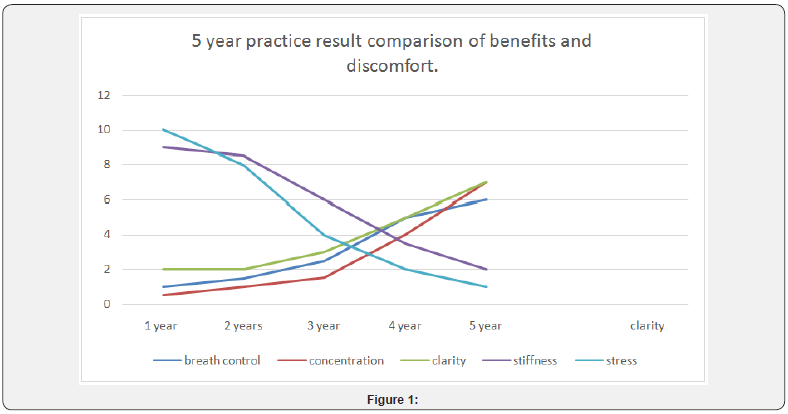

I applied variables based on perceived percentage and appointed points from 1-10 where 10 was a maximum score (Table 1). In a question on level of confusion and understanding it was found that it more or less stays the same up to the moment where the goal of practice becomes self-evident, and that is in fact mostly after 6-10 months of practice. Students perceived a gradual decline of stiffness, but much less so to the experience of pain. This last factor can be attributed to the growing awareness, causing me to change some wording in the classroom, shifting the idea of awareness as a mental phenomenon towards a physical phenomenon. Practice offered practitioners more awareness of physical limitations. For the group on students it was uses every class after the session where the questions were asked and put in the form by myself and not the student. Some attendants kept struggling with stiffness no matter what, but in general everybody experienced improvement. In the beginning period the experience of change was much larger while the actual change was limited because not durable. Durable change happened over time, causing me to introduce the concept of ‘buffer space for health degeneration’ in the idea of acquirement of flexibility, here equating stiffness with health risk due to lack of circulation of blood and body fluids, and limitation of neural effectiveness.

Graphing the results, we see that most practitioners stop practice between 1-2 years due to lack of fashion ability, relative slow start of progress even though some basic stiffness can already be seen as resolved in a few lessons. Commercial programs like Group on do rarely attract lasting students. The large turnover of such programs can be financially rewarding if this is taken into account, but mostly it is useful for research purposes. As a whole I see that physical benefits are quick to appear depending on teaching style, but are apparently not a motivation to continue practice. In questions outside the scope of practice, fashion ability and costs are also important factors that make people decide what they practice. It is sad to note that marketing trumps usefulness as a research outcome (Figure 1).

Critical Aspects

A weakness of the project is that we could not guarantee daily practice of participants, although the 15 that went through the whole process claimed they mostly practiced every day. Also is not taken into account other disturbing factors such as possible abuse of substance or medication, dietary habits and performance of other sports that could have either beneficial or counter-productive influences. So depending on follow studies that could include these factors results should be seen as provisional. A follow-up study should also measure blood flow, brainwaves, lymph and hormonal change. As a result of this investigation it can be predicted that there should be a developmental change in all these factors to settle the perceived subjective change as an objective change.

As a control group I took 20 clients of acupuncture who needed to work on a variety of issues not dissimilar to those of the Wudang yoga practitioners. I did not use a third control group who used neither of the two services or a forth that used another form of yoga. Due to limited strict adherence to the content of the research only, the provisional research shows a lot of noise. A follow-up control research over 3 months will be required to fine-tune the results of average’s over the first 10 classes (Figure 2).

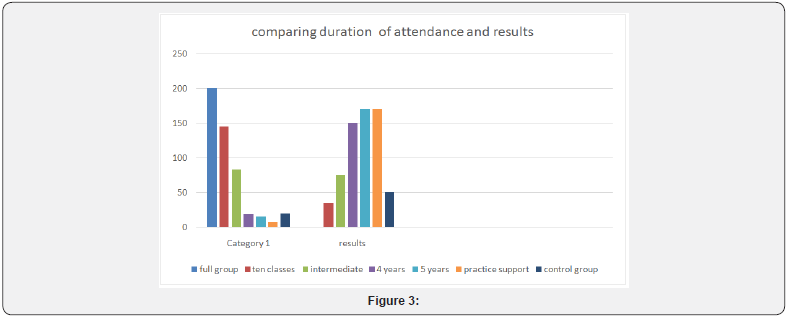

From the yoga practitioners some 50 on and off also used acupuncture for issues. Some 7 used it for issues related to practice. For result questioning I used questions applying a same scale as for attendance of 1-200. The control group did not score on the same issues, because they did not perform such practices, but it shows how practice as a lifestyle influences experience of quality in life. The graph also shows how the small 5 year group had much better results and experience from the practice due to durable use. They still considered there to be space for progress at the end, so skill development in 5 years cannot be considered perfect (Figure 3).

Conclusion

All participants experienced results and benefits, even on a short term of ten classes. But learning breath control and what that entails can take up to two years. Factors such as stress experience, anxiety, physical comfort also need to be seen as relative in that context. Growing awareness of one’s physical experiences also tends to show more minute details than before and does skew the neutrality of self-observation and reflection. My idea is that the Confucian quality of continuous self-assessment as if on trial will be a welcome quality to help complement the practice, but that requires a more restricted environment in which students have to practice. Most important is that as a conclusion that more research is needed to come to a final outcome on effectiveness of Wudang yoga. Also it is clear that Wudang Yoga to become as popular as Indian styles of Yoga will need to be combined with good marketing. It will be interesting to measure if popularity also improves the outcomes of research, and then what new questions will have to be asked for future research.