Physiotherapy for Pain Control in Dogs and Cats

Maira Rezende Formenton*

Veterinary Ambulatory of Pain and Palliative Care, São Paulo University, Brazil

Submission: March 01, 2018; Published: April 19, 2018

*Corresponding author: Maira Rezende Formenton, Professor at Bioethicus Institute, Fisioanimal Rehabilitation Center, Veterinary Ambulatory of Pain and Palliative Care, São Paulo University, Brazil, Email: mairaformenton@gmail.com

How to cite this article: Maira R F. Physiotherapy for Pain Control in Dogs and Cats. J Yoga & Physio. 2018; 4(5): 555646. DOI: 10.19080/JYP.2018.04.555646

Introduction

Analgesia and pain control are essential issues in the area of veterinary rehabilitation. Considered as the fourth vital sign, acute or chronic pain requires early intervention, the anticipation of evolution, and assessment to achieve individualized treatment protocols. The acronym PLATTER (PLan, Anticipate, TreaT, Evaluate, and Return) [1], guides the professional for the establishment of analgesia, including in the area of physiotherapy.

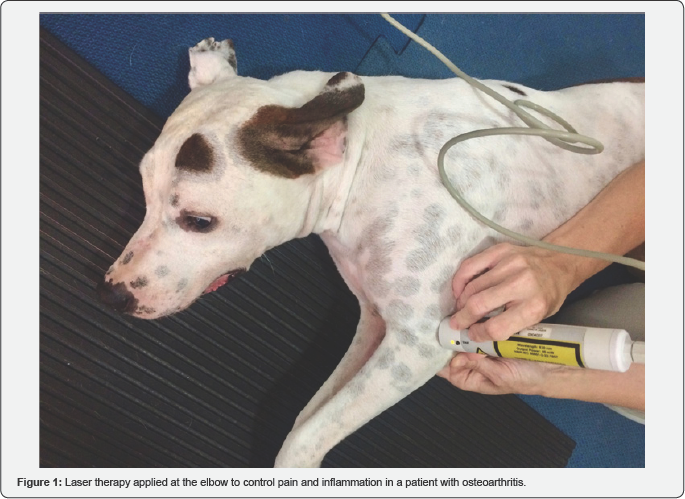

Following the acronym, the first stage involves planning. In a rehabilitation program, it refers to the choice, within the methods available, those suitable for that patient’s condition. For example, laser therapy (Figure 1) may be the choice for a feline with spine pain, as it is an easy and non-invasive method with good acceptance of the species. But for a dog that accepts manipulation, acupuncture associated with massage therapy (Figure 2) can bring the result of analgesia as quickly and pleasantly treatment [2].

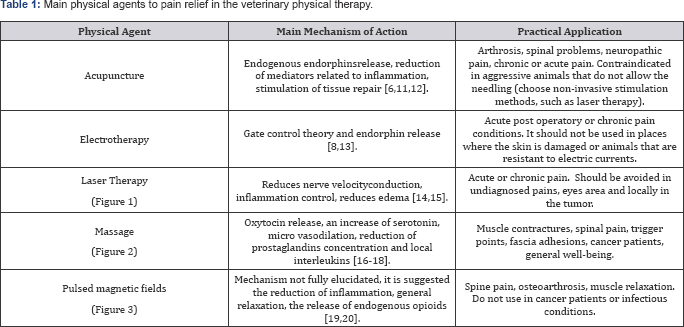

Anticipation refers to predicting the occurrence of pain and then prevent patient exposure to painful experience. A typical example is patients with osteoarthritis, which in the colder months tend to present hyperalgesia (Figure 3). It is possible, for example, to intensify physiotherapy sessions in the months before winter and thus anticipate the treatment, and allow a higher quality of life during this period for the animal. TreaT is the choice of methods for the treatment itself. We must remember that must always be multimodal, and the association of pharmacological methods with rehabilitation brings the best benefits. It should be considered from the disease of the animal to the financial conditions of the owners to establish the best treatment. Table 1 shows the primary methods of rehabilitation for the control of pain and analgesia.

Finally, the Evaluate and Return in physiotherapy should be done at each session, to adjust the protocols and methods applied. The evolution of the patient can be fast, especially in cases of acute pain, and the change of approach can occur each session. For chronic, recurrent, maladaptive or neuropathic pain, the improvement can happen within 4 to 6 sessions, so, reassessment can wait for this period. In this process of pain assessment, considering the anamnesis, it should take into account aspects reported by the animal’s tutor such as lameness, reluctance to move, decreased appetite, excessive licking and even self-mutilation. To assist in the identification and quantification of pain, it is recommended to use unidirectional scales such as the Verbal Numerical Scale associated with multidirectional scales such as the Helsinki questionnaires and the Glasgow pain scale, or quality of life such as Yazbek & Fantoni [3] questionnaires.

Inflammation is another pathological process directly related to pain. Physiotherapy has complementary means to control inflammation, in order not only to reduce pain but also to reduce the use of medications that may cause side effects in the long term [4,5]. The control of the inflammatory process has other benefits besides analgesia, among them: the improvement of functional limitations and increased mobility, reduced the time of recovery postoperatively, improvement in the quality of life [6,7].

As a result of this relationship between reduction of inflammation and pain, a study in dogs [8] showed that the use of the association between low power laser therapy and electrotherapy in the form of TENS confers reduction of pain scores and the lesser need for analgesic rescue. Two groups of dogs were established postoperatively for knee surgery, one group undergoing the therapies as mentioned above three times a week, for two weeks, the other was the control-placebo group. The evaluation was done by pain scales, baropodometry, and thermography. The animals submitted to the laser therapy sessions associated with electrotherapy obtained better pain scores and less analgesic rescue. When addressing chronic inflammation, physical therapy may benefit from better support and quality of life in patients with arthrosis, back pain, and even cancer patients [9-20].

Conclusion

The method for the pain control during physiotherapy should be established based on planning, assessment and multimodal choice of the treatment, to obtain the highest level of comfort for the patient, as quickly and efficiently as possible.

References

- Epstein M, Rodan I, Griffenhagen G, Kadrlik J, Petty M, et al. (2015) 2015 AAHA/AAFP pain management guidelines for dogs and cats. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 51(2): 67-84.

- Formenton MR (2017) Physiotherapy in dogs and cats. In: Pain Guide of the Brazilian Society for the Study of Pain. Editora Atheneu, São Paulo, Brazil, pp. 2457-2470.

- Yazbek KVB, Fantoni DT (2005) Validity of a health-related quality-of-life scale for dogs with signs of pain secondary to cancer. J Am Vet Med Assoc 226(8): 1354-1358.

- Shumway R (2007) Rehabilitation in the first 48 hours after surgery. Clin Tech Small Anim Pract 22(4): 166-170.

- Vedpathak HS, Tank PH, Karle AS, Mahida HK, Joshi DO, et al. (2009) Pain management in veterinary patients. Vet World Elsevier Inc 2(9): 360-363.

- Corti L (2014) Nonpharmaceutical approaches to pain management. Top Companion Anim Med 29(1): 24-28.

- Formenton MR, Paulo S (2011) Physical therapy in cats and dogs : applications and benefits. Veterinary Focus 21(2): 11-17.

- Formenton MR (2015) Electrotherapy and laser therapy in the control of pain and inflammation in the postoperative period in dogs submitted to tibial plateau leveling osteotomy surgery: a prospective study. Universidade de São Paulo, Brazil.

- Johnston KD, Levine D, Price MN (2002) The Effect of tens on osteoarthritic pain in the stifle of dogs. In: International Symposium on Physical Therapy and Rehabilitation in Veterinary Medicine. (2nd), Knoxville, TN, USA.

- Um SW, Kim MS, Lim JH, Kim SY, Seo KM, et al. (2005) Thermographic evaluation of the efficacy of acupuncture on induced chronic arthritis in the dog. J Vet Med Sci 67(12): 1283-1284.

- Habacher G, Pittler MH, Ernst E (2015) Effectiveness of acupuncture in veterinary medicine: systematic review. J Vet Intern Med 20(3): 480-488.

- Mathews K (2008) Neuropathic pain in dogs and cats: if only they could tell us if they hurt. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 38(6): 1365-1414.

- Vance CGT, Dailey DL, Rakel BA, Sluka KA (2014) Using TENS for pain control: the state of the evidence. Pain Manag 4(3): 197-209.

- Millis DL, Saunders DG (2014) Laser therapy in canine rehabilitation. In: Canine Rehabilitation and Physical Therapy.(2nd), Elsevier, p. 760.

- Farivar S, Malekshahabi T, Shiari R (2014) Biological effects of low-level laser therapy. J Lasers Med Sci Vol 5(2): 58-62.

- Field T, Hernandez Reif M, Diego M, Schanberg S, Kuhn C (2005) Cortisol decreases and serotonin and dopamine increase following massage therapy. Int J Neurosci 115(10):1397-413.

- Lee SH, Kim JY, Yeo S, Kim H, Lim S (2015) Meta-analysis of massage therapy on cancer pain. Integr Cancer Ther 14(4): 297-304.

- Corti L (2014) Massage therapy for dogs and cats. Top Companion Anim Med 29(2): 54-57.

- Markov MS (2007) Magnetic field therapy: a review. Electromagn Biol Med 26(1): 1-23.

- Salomonowitz G, Friedrich M, Güntert BJ (2011) Medical relevance of magnetic fields in pain therapy. Schmerz 25(2): 157-160, 162-165.