Mind-Body Interventions Impact Chronic Pain

Melissa E Kerr and Nancy Landgraff*

Department of Physical Therapy, Youngstown State University, USA

Submission: March 08, 2018; Published: March 28, 2018

*Corresponding author: Nancy Landgraff, Department of Physical Therapy, Youngstown State University, One University Plaza, Youngstown, Ohio 44555, USA, Tel: (330)941-2703; Email:nlandgraff@ysu.edu

How to cite this article: Melissa E K, Nancy L. Mind-Body Interventions Impact Chronic Pain. J Yoga & Physio. 2018; 4(3): 555640. DOI: 10.19080/JYP.2018.04.555640.

Abstract

Pain that is inadequately managed can evolve into multiple, unfavorable physical and psychological outcomes. A biopsychosocial model to manage pain includes physical and physiological factors and the social influences on pain. Mind-body therapies (MBT) address emotional, mental, social, spiritual, experiential, and behavioral factors and can be included in a physical therapy treatment program for managing chronic pain (CP). This case report discusses MBT for a 69-year-old woman with CP affecting multiple areas, and limited function in her daily activities. Pain was initially 8/10 and constant. The patient received 10 treatment sessions of mind-body interventions including yoga, breath awareness and mindful movement training. At the end of these sessions she reported 0/10 pain and the ability to self-manage her chronic pain condition throughout her daily activities.

Keywords: Mind-body Therapies, Chronic Pain, Physical Therapy

Introduction

Pain is one of the most common reasons individuals seek medical services, including physical therapy. Pain that is persistent and extends longer than the expected time frame for healing, generally 3 to 6 months, is chronic [1]. Chronic and inadequately managed pain can evolve into multiple, unfavorable physical and psychological outcomes. CP has a large body of evidence supporting the relationship between pain and stress [2]. Specifically, there is research supporting the association of musculoskeletal pain and pain related to psychological stress such as negative coping, catastrophizing (magnified perceptions of pain, recurrent or exaggerative negative thoughts), and fear [2].

Adequate management of pain may not be possible without the homeostasis of certain hormones [3]. Cortisol, a catabolic hormone designed to protect the body from the harm of stress and reduce inflammation, is the result of the hypothalamic- pituitary-adrenal (HPA) stimulation and is triggered by any physical, emotional, or inflammatory stress [4]. Individuals with CP tend to have lower serum-cortisol concentration, theorizing that unmanaged and CP may stimulate the HPA response to the point of exhaustion, causing a depleted supply of cortisol [4]. Without adequate cortisol, the stress-induced inflammation that is associated with multiple diseases such as osteoporosis, fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue, chronic low back pain, and rheumatoid arthritis may arise and symptoms such as pain, depression, fatigue, and memory-impairment may be exacerbated [2]. One factor in managing CP may be to identify and intervene with the non-pain related stress factors for an individual. CP has more recently been recognized as a complex biopsychosocial matter in which additional factors of psychological and social influences contribute to the severity of a problem, prompting consideration of a multi-faceted, holistic, and individualized approach to treatment [5]. MBT include a wide range of interventions and practices that facilitate the mind's capacity to affect health [6]. The most frequently reported and researched examples of MBT include meditation, relaxation and breathing techniques, yoga, tai chi and qigong, hypnosis, and biofeedback [7]. Other interventions cited in the literature include mind-body stress reduction, cognitive behavioral therapy, biofeedback, guided imagery, and progressive relaxation [8]. According to the National Institutes of Health (NIH), mind- body medicine focuses on interactions among the brain, the body, the mind, and behavior. More specifically, mind-body medicine examines the ways in which emotional, mental, social, spiritual, experiential, and behavioral factors directly affect one another and overall health. The ultimate goal of mind-body ntervention, via MBT, is to elicit the natural relaxation response, which is objectified in many ways including slower breathing, lower blood pressure, and an increased report of well-being [9]. In order to appreciate these complex, dynamic relationships, consider the following case involving chronic pain and mind- body interventions during the course of physical therapy.

Case Description

In October 2017, a 69-year-old female entered the physical therapy clinic with diagnoses including pain in left hip and ankle, right knee, both shoulders as well as difficulty walking, unspecified osteoarthritis, cervical radiculopathy, and other non-descriptchronic pains. This patient lived alone on a farm. She reported chronic, daily pain rated 8/10 on a 0-10 numeric pain scale that limited her function and affected her gait pattern (antalgic) and gait distance (unable to traverse her fields to care for the land and animals). Her physician's goals with physical therapy included the ability to participate in aerobic exercise for cardiovascular health and weight loss. Her pain was greatest in the left hip followed by pain in the right knee and left ankle. She had bilateral shoulder pain and, during the course of treatment, received an additional diagnosis of cervical radiculopathy with symptoms of paresthesia in her upper extremities. This patient had a fall history with recent fall three months prior where she fell in the field and landed on her left side including her hip. Her medications included benicar HCL 12.5mg (anti-hypertensive with diuretic), clorazepate 7.5mg as needed (anxiety), omeprazole (reflux) 20mg, vitamin D3, flonase (allergy), and over-the-counter Tylenol (analgesic).

Clinically, this patient presented with an elevated body mass-index, asymmetric pelvic landmarks, iliosacral dysfunction (IS) with a left anterior innominate, bilateral calcaneal valgus with absent medial longitudinal arches producing flat feet, and hallux valgus. She tested positive for left piriformis involvement with lower quarter symptom reproduction, demonstrated reduced hip extension (actively to neutral) and knee flexion contractures (lacking eight degrees from neutral bilaterally), and demonstrated lower quarter weakness throughout including significant impairment in the gluteus medius musculature noting an inability to sustain the test position in coronal plane bilaterally. Psychological and emotional assessment included self-reports of depression due to pain and inability to participate in meaningful activities (tend to her farm), and therapist interpretation based on subjective input assessed fear (pain preventing independent living at her home), loneliness (awareness of social isolation from friends and family), and anger (ex-husband, status of divorce, and spouse's daughter from a former marriage). Her sleep was interrupted approximately 25-50% and her sleep quality was self-described as poor.

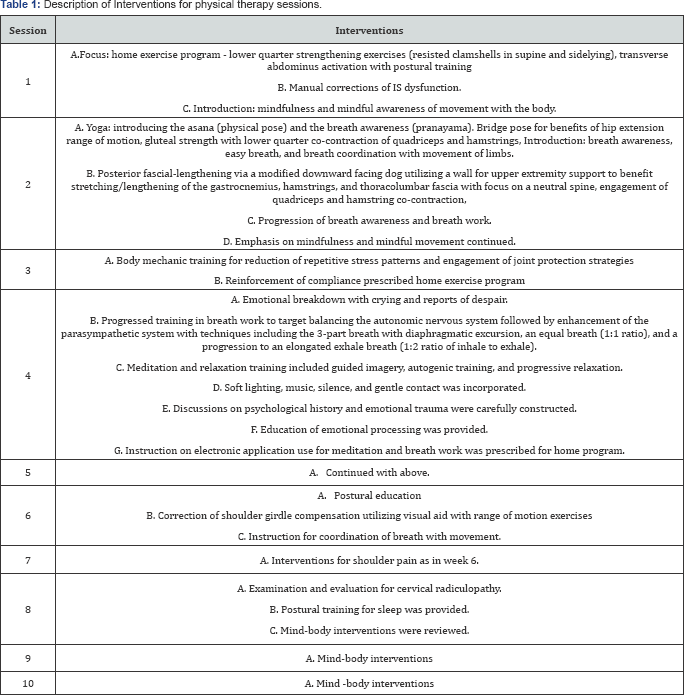

The plan of care was established to proceed at one visit per week anticipating 12 sessions to achieve set goals for selfmanagement of pain. See Table 1 for session descriptions. In the first session, the focus was on establishing a home exercise program after some manual therapy techniques, and to introduce early mind-body concepts. In the second session, yoga techniques were initiated with a focus on breathing, and continued reinforcement of mind-body techniques. At the third physical therapy session this patient reported compliance with home program and reduced IS pain. She denied any significant improvements in her other areas pain.

During the fourth session, this patient reported poor home program compliance and displayed an emotional breakdown with crying and reports of despair. Therapy interventions immediately shifted to include a more biopsychosocial approach and are described in Table 1. During discussions on psychological history and emotional trauma the patient was able to self-identify grief, guilt, anger, and family stressors. Patient reported a sense of total relief at end of session reporting no pain, demonstrated a relaxed demeanor with ease of movement in transfers and gait, and manifested a smile.

At this patient’s fifth session, she reported she was "infinitely better" and was near resolution of pain. At her sixth session, she was no longer taking over-the-counter analgesic medication, and her only complaints included catching, clicking, and aching with her shoulders during overhead movements. Due to her progress, patient proceeded with two weeks of self-management before returning to physical therapy.

At her seventh visit, she reported her ability to walk 18,000 steps on her farm and complete manual labor and animal care with no pain in the lower body. She reported feeling "more joyful". She had persistent, intermittent pain in her shoulders prompting intervention. After a subsequent scheduled physician appointment, she returned to physical therapy for her eighth visit with a new diagnosis, cervical radiculopathy, due to onset of paresthesia in the upper extremities. Examination and evaluation revealed sleep posture was primary culprit for symptoms and postural training for sleep was provided with follow up over the next two scheduled visits. Mind-body interventions were reviewed at these final two sessions.

This patient was discharged from physical therapy services January 23, 2018 after attending ten treatment sessions. At this patient's eighth visit, the Lower Extremity Functional Scale improved from an initial score of 64 to a score of 40. Her knee extension and hip extension showed no objective change. Her gait pattern was not remarkably improved. Other objective data did not reflect statistical improvement, but marked improvement in subjective reports and functional progress were consistently documented throughout her course of care. Most notably, this patient’s CP in the lower body was rated 0/10, she was compliant with her prescribed home program which included multiple MBT, and she reported feeling happy, optimistic, and capable of self-management.

Discussion

MBT are gaining momentum in popularity in the general public and medical communities, but MBT do not yet garner strong evidence-based support in clinical studies. Many studies utilizing separate or combined MBT show low to moderate evidence for efficacy, which is not unusual for many modalities utilized in physical therapy. These studies, however, have limitations in design, bias, sample size, and duration inadequacy. The current mind-body literature frequently references mindfulness, meditation and CP. Consistently, research findings show no adverse effects to these interventions. Four Level 2 evidence studies [10], la Cour & Petersen [11], Monroe et al. [12], Wong et al. [13] and Monroe et al. [14] investigated the effects of mindfulness and meditation on chronic pain. Although gains in all four studies were not statistically significant, gains were clinically meaningful. Each of these studies' findings showed positive trends for greater improvement in the intervention (mindfulness-meditation) groups for increased function and reduced pain when compared to any control or comparative group. The addition of MBT interventions, including mindfulness and meditation, to a conventional physical therapy program for a patient with CP may therefore result in selfreports of improvement despite lack of statistically significant or objective data change. These findings may prompt physical therapists to consider the definition of improvement, investigate psychological and emotional restrictions in managing CP", and consider utilizing a self-report questionnaire such as the Emotional Processing Scale or Health-Related Quality of Life Measures to monitor progress.?

Despite many reasons supporting a musculoskeletal source of pain in the lower quarter, this patient did not respond favorably to conventional physical therapy interventions (IS dysfunction correction, range of motion, strengthening, postural and body mechanic training). She did respond favorably to a biopsychosocial model where the emphasis on managing CP identified chronic stress sources and intervened with MBT. MBT, regardless of the particular modality, trigger the relaxation response, which impacts the HPA axis. This course of physical therapy possibly assisted the patient's body in returning to a hormonal homeostasis through mind-body interventions.

Conclusion

Pain varies among individuals. Pain is experienced and described in ways that are unique to an individual's experiences physically, psychologically, and emotionally. CP is challenging to treat. Individuals with CP tend to use extensive resources to manage and often do not improve to either reduce or eliminate medication management needs or other routine medical interventions [15]. The resolution ofCP is uncommon, particularly in a short duration of time and without medication. In this case report, the resolution of lower quarter pain was unexpected, but appeared to be directly related to the increased identification and engagement of the non-pain elements associated with pain; emotional and psychological factors. The lack of progress in objective data combined with subjective improvement suggests that clinical functional outcome measures should also include reports that encompass more of the biopsychosocial model of care. Future research and clinical studies should extrapolate on methods to better identify psychological and emotional restrictions and investigate which mind-body methods may be more advantageous with CP patients.

References

-

jawa

- Brown K (2005) The neurophysiology of pain: Where brain and mind meet.

- Hannibal KE, Bishop MD (2014) Chronic stress, cortisol dysfunction, and pain: A psychoneuroendocrine rationale for stress management in pain rehabilitation. Phys Ther 94(12): 1816-1825.

- Tennant F (2013) The Physiologic effects of pain on the endocrine system. Pain Ther 2(2): 75-86.

- Tennant F (2017) Cortisol screening in chronic pain patients.

- Jensen M (2006) Pain management-chronic pain. In: Elkins G (Ed.), Clinician's guide to medical and psychological hypnosis: Foundations, applications, and professional issues. Springer, New York, USA.

- Wolsko PM, Eisenberg DM, Davis RB, Phillips RS (2004) Use of mind- body medical therapies: Results of a national survey. J Gen Intern Med 19(1): 43-50.

- Wahbeh H, Elsas SM, Oken BS (2008) Mind-body interventions: Applications in neurology. Neurology 70(24): 2321-2328.

- Mayden KD (2012) Mind-Body Therapies: Evidence and Implications in Advanced Oncology Practice. J Adv Pract Oncol 3(6): 357-373.

- National Institute of Health (2013) Mind-body medicine practices in complementary and alternative medicine.

- Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (2011) Levels of evidence.

- La Cour P, Petersen M (2015) Effects of mindfulness meditation on chronic pain: A randomized controlled trial. Pain Med 16(4): 641-652.

- Morone NE, Greco CM, Moore CG, Rollman BL, Lane B, et al. (2016) A mind-body program for older adults with chronic low back pain: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 176(3): 329-337.

- Wong SY, Chan FW, Wong RL, Chu MC, Kitty Lam YY, et al. (2011) Comparing the effectiveness of mindfulness-based stress reduction and multidisciplinary intervention programs for chronic pain: A randomized comparative trial. Clin J Pain 27(8): 724-734.

- Morone NE, Rollman BL, Moore CG, Li Q, Weiner DK (2009) A mind- body program for older adults with chronic low back pain: Results of a pilot study. Pain Med 10(8): 1395-1407.

- Thornton RG (2011) Considerations in treating patients with chronic pain. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent) 24(3): 262-265.