Extreme Adverse Behaviour by Physiotherapy Students and Qualified Physiotherapists and the Risk of Termination of an Individual’s Career

Timothy David1* and Sarah Ellson2

1Faculty of Biology, Medicine and Health, University of Manchester, UK

2Fieldfisher LLP, UK

Submission: February 26, 2018; Published: March 22, 2018

*Corresponding author: Timothy David, Faculty of Biology, Medicine and Health, University of Manchester, Manchester M13 9PL, UK, Email: tdavidmd@gmail.com

How to cite this article: Timothy David, Sarah Ellson. Extreme Adverse Behaviour by Physiotherapy Students and Qualified Physiotherapists and the Risk of Termination of an Individuals Career. J Yoga & Physio. 2018; 4(3): 555636. DOI: 10.19080/JYP.2018.04.555636

Abstract

Certain types of extreme adverse behaviour can put an existing or future career as a physiotherapist at risk. There is considerable overlap between the problems exhibited by students and those seen in qualified professionals, and there is some evidence that unprofessional behaviour in a healthcare student may be associated with subsequent unprofessional behaviour and termination of a career. The hope, as yet unproven, is that the early detection of problem behaviours in students may help to prevent such behavior continuing into clinical practice.

Keywords: Physiotherapy; Education; Fitness to practise; Professional suitability

Introduction

There is marked variation in the way that present and future health and social care professionals are regulated in different parts of the world [1]. The two fundamental components are guidance on a code of professional conduct that sets out the expected standard of behaviour, and procedure setting out what may happen if an individual’s behaviour falls significantly below that which is expected. In the UK, qualified physiotherapists are regulated by a body, the Health and Care Professions Council (HCPC), that also regulates 15 other so-called “allied health care professionals”, such as, for example, occupational therapists, dietitians, speech therapists, paramedics and operating department practitioners. In the UK it is only possible to practise in these professions if one is registered with the HCPC. Newly qualified students are unable to practise their chosen profession unless their name is entered into the relevant register. The HCPC publishes guidance on various aspects of professional behaviour, for qualified professionals and for students [2-6]. Education institutions are likely, in addition, to provide their own guidance on expected behaviour for students.

This article describes the sort of adverse behaviours (see below) that are particularly likely to put a professional and licensed career at risk, and the way that such problems are approached. In principle a career of a physiotherapist or physiotherapy students can be halted in three main ways:

A. As a result of severe conduct/behaviour problems, a student physiotherapist can have their studies terminated by their educational institution. The individual may be able to apply to train as a physiotherapist at another institution, but an applicant would be expected to disclose their expulsion, and in practice it may be very difficult to gain a place to train as a physiotherapist elsewhere, depending on the circumstances. Even if another education institution accepts an individual, that is no guarantee that placement providers will agree to a placement for an individual student who has a history of problem behaviours.

B. An employer may terminate the employment of a physiotherapist. If when applying for another post references are diligently sought and negative references provided, this could adversely effect the chances of getting employment elsewhere (although this is notoriously unreliable and may not in fact prevent a poorly performing professional getting re-employed).

Depending upon the circumstances, it may or may not be possible to gain employment elsewhere.

C. Depending upon the arrangements for the regulation of health professionals, which vary from country to country and from state to state, a physiotherapist could lose their licence to practise, and as a result be unemployable as a physiotherapist in that state or country. A recent example, obtained from the Health and Care Professions Tribunal (HCPCT) website, from which details of fitness to practise hearings can be freely downloaded [7], is that of a physiotherapist who obtained covert pictures of patients while they were partially undressed during and after treatment. One patient noticed that she was being filmed on a concealed mobile phone. She complained to the police. When they examined the physiotherapist’s phone, a video recording of another patient was found. The physiotherapist pleaded guilty to criminal charges, and received a prison sentence. His case was considered at an HCPCT hearing. In his favour, it was noted that he had pleaded guilty and had expressed remorse. Unfavourable features were that he only considered the effect his offending had on himself and his family, and he had demonstrated no insight into the effect on his victims. He failed to demonstrate any understanding of the sense of betrayal and violation felt by the patients, whose trust he had abused, and he failed to demonstrate any insight into why he behaved in the way he did and so what steps he might need to take to ensure he never offended in this way in the future. It was concluded that he presented a risk to future patients, his name was erased from the HCPC register, resulting in him being unable to practise as a physiotherapist in the UK, and, if appropriate cross-checks are done making it unlikely that he would be able to gain a licence to practice elsewhere.

Behaviours that may result in loss of a career in a practising physiotherapist

The five categories of behaviours [7] are set out below, with some examples.

Misconduct: behaviour which falls short of what can reasonably be expected of a health professional, such as:

a) Failure to provide adequate care;

b) Failure to maintain professional boundaries with a service user;

c) Breach of patient confidentiality;

d) Misuse of computers in the workplace; or

e) Falsely claiming sick leave.

Lack of competence: lack of knowledge, skill or judgement (usually repeated and over a period of time). For example:

a) Poor record-keeping;

b) Inadequate professional knowledge;

c) Inadequate risk assessments; or

d) Poor clinical reasoning.

Criminal offence: for example:

a) Theft;

b) Fraud;

c) Child pornography;

d) Possession of a controlled drug;

e) Serious assault or other form of violence; or

f) Harassment.

Physical or mental health: long-term, untreated or unacknowledged physical or mental- health condition. For example:

a) Unmanaged serious mental illness;

b) Long-term, untreated alcohol or drug dependence; or

c) Failure to share information about health with employer.

d) A decision made by another regulator responsible for health and social care

e) A decision by a healthcare regulator in the same country; or

f) A decision by a healthcare regulator in another country.

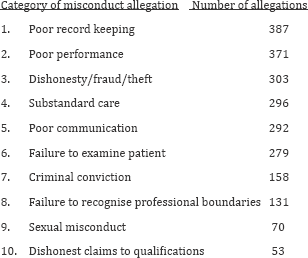

In a recent study of 6,714 doctors, nurses and allied healthcare professionals (physiotherapists were one of 16 different health and social care professions) whose professional suitability was considered at a hearing of the relevant UK regulator, there were in total 17,301 allegations of misconduct [8]. Excluding health- related concerns, the most frequent misconduct allegations made against allied healthcare professionals were:

There have been some studies of misconduct among physiotherapists, but severe transgressions are uncommon and studies tend to report on small numbers [9].

Behaviour difficulties encountered in health care students

Whilst there are some similarities to the problems seen with qualified health professionals, healthcare student problem behaviours come into the following categories [10]:

Plagiarism: Passing off the work of others as one’s own in a piece of written work. This can result from a lack of knowledge about correct ways to reference the work of others, or it may result from dishonesty such as copying the work of another person and pretending it is one’s own work.

Cheating and other forms of dishonesty: This includes cheating in examinations, falsifying research data, misrepresentation of qualifications and experience in a curriculum vitae or other documents, forging a supervisor’s name in assessments or placement documents, forging a supervisor’s assessment, getting another student to enter one’s name on an attendance register, and making false entries in portfolios or logbooks.

Criminal offences: The degree to which these impact upon a healthcare student’s suitability to enter their chosen profession will depend on the nature of the offence(s), the number of offences, the seriousness of the offence and the sentence. Criminal offences committed before commencing as a student should be considered during the application process, and may (after the applicant has been given an opportunity to put their side of the story) result in the offer of a place being withdrawn.

Mental illness: Mental illness need not in itself render a student unsuitable for a health professional career, but if the condition cannot be controlled, because either there is an inherently poor response to treatment or the student fails to seek or comply with medical treatment, or if the student is unwilling to share information about their health, then there might be a risk to the patients.

Drug or alcohol misuse: Problems seen include drink driving as a result of dependency, alcohol consumption that affects clinical work or the work environment, and dealing, possessing or misusing drugs. Drug or alcohol misuse are usually regarded as part of the spectrum of mental health problems. Concerns are likely to be increased when there is poor sharing of medical information (with an employer, or with an educational institution) or a lack of co-operation with support, treatment and random screening.

Misuse of social media e.g. facebook: As an example, a mature student who used his public Facebook account to post his views that same-sex marriage was a sin, was excluded from his social work course by his University because of the public way he had posted these which may have caused offence, coupled with his lack of insight or reflection on this behaviour [11].

Unprofessional behaviour: This broad label can be used to describe a broad category of problem behaviours:

a) Repeated failure to attend appointments with teaching staff or workplace supervisors

b) Persistent rudeness to patients, colleagues or others

c) Persistent disregard for regulations, requirements and official communications

d) Persistent failure to accept and follow educational advice

e) Persistent disrespect shown to teachers, colleagues or others

f) Persistent neglect of administrative tasks e.g. not checking or responding to work or study-related emails

g) Poor time management e.g. repeatedly arriving late for placements

h) Breach of patient confidentiality e.g. openly discussing a patient when this can be overheard by those uninvolved in the treatment of the patient

i) Misleading patients e.g. concealing student status

j) Inappropriate examinations or failure to maintain appropriate boundaries in behavior

k) Failure to obtain proper consent from a patient

l) Sexual, racial or other forms of harassment

Discussion

Different terms are used around the world to describe professional suitability. In the UK and some other English speaking countries such as Australia and New Zealand, the term “fitness to practise” is used by the health and social care professions (and sometimes other professions) to describe a minimum standard of professional behaviour that is suitable for clinical practice. Professionalism is a term most frequently used in relation to desirable aspects of the behaviour of health care students.The word professionalism has been regarded as having a number of different meanings However there are a number of alternative understandings of the meaning of this term [12-17]. In 2003, Jette and Portney asked 183 physiotherapy students at two colleges in Boston to indicate how frequently they performed 152 professional behaviours [18]. From this data they derived a model of professional behaviour and identified 7 constituent behaviours:

1. Professionalism

2. Critical thinking

3. Professional development

4. Communication management

5. Personal balance

6. Interpersonal skills

7. Working relationships

Appropriate and meaningful assessment of students’ performance on clinical placement is essential to ensure that new practitioners entering the profession are of an acceptable standard [11]. It is believed that an emphasis on professionalism and professional behaviour is an important component of a physiotherapist’s education [12,13]. In one study, from Australia, 61% of 79 physiotherapy educators reported having experienced concerns regarding the professional suitability of one or more physiotherapy students which could impact on patient care [19]. The authors concluded that just over 50% of the issues seen could have been avoided, and they called for further research to identify evidence-based strategies to support students.

Published evidence from the USA shows that physicians who were disciplined by a state medical board were three times more likely to have a record of unprofessional behaviour during medical school than were controls [20,21]. The hope therefore is that early detection and intervention may help healthcare students to overcome problem behaviours [22].

Conclusion

Whilst possessing the relevant knowledge and skills is fundamental for the practise of all health professions, there is increasing recognition that the way that professionals behave is no less important. Patients and the public have expectations regarding acceptable standards of professional behaviour, and are increasingly concerned not only about the appropriateness of health care but the manner in which it is delivered. Certain types of adverse behaviour can put an existing or future career as a physiotherapist at risk. There is overlap between the problems exhibited by students and those seen in qualified professionals. Improved professional education coupled with the early detection of problem behaviours should help to reduce the number of individuals who put their career at risk by departing from the expected standards of behaviour.

Acknowledgement

We wish to thank Annelies David and Jo Racle for their helpful comments on the manuscript.

Would you know what to do? Self-Test for Physiotherapy Students and Qualified Physiotherapists

1. A physiotherapy student turns up to a clinical placement at 9am, smelling very strongly of alcoholic drinks, clearly unwell and unsteady. The student excuses herself after a few minutes and can be heard vomiting loudly.

2. A physiotherapy student borrows an essay written by a student the year before, copies it, and hands it in unchanged to his education supervisor, pretending it is his own work.

3. A physiotherapy student repeatedly fails to respond to emails from the education organisation, frequently arrives very late for appointments with patients, and is often absent altogether without any explanation.

4. A physiotherapy student arrives at his education institution in a distressed state, having just been arrested by the police and charged with sexually assaulting another physiotherapy student.

5. A physiotherapy student suffers from severe obsessive- compulsive disorder and has recently been arriving very late because she is spending hours every morning repeatedly washing herself and her clothing, and repeatedly returning to her flat to check and see if the front door has been locked. Recently she has been noted to be increasingly anxious, and reporting that she feels depressed.

What are the duties of a student or a physiotherapy teacher who encounters such problems? The answer may depend on the circumstances, but it is helpful to think through and discuss such matters, as it can sometimes be difficult to identify the correct course of action. The guiding principle should be the need to protect the interests of present and future patients, so a question to ask yourself is “will what I suggest protect patients and enable them to trust my profession?”.

References

- Ellson S (2017) The Healthcare Law Review. London, Law Business Research Ltd, UK.

- Health and Care Professions Council (2016) Standards of conduct, performance and ethics. Health and Care Professions Council, London, UK.

- Health and Care Professions Council (2013) Physiotherapy. Standards of proficiency. Health and Care Professions Council, London, UK.

- Health and Care Professions Council (2017) Guidance on health and character. Health and Care Professions Council, London, UK.

- Health and Care Professions Council (2015) The fitness to practise process. Health and Care Professions Council, London, UK.

- Health and Care Professions Council (2016) Guidance on conduct and ethics for students. Health and Care Professions Council, London, UK.

- Health and Care Professions Tribunal Service. Hearings and decisions, recent decisions 23 January 2018.

- Searle RH, Rice C, McConnell AA, Dawson JF (2017) Bad apples? Bad barrels? Or bad cellars? Antecedents and processes of professional misconduct in UK health and social care: insights into sexual misconduct and dishonesty. Professional Standards Authority, London, UK.

- Hoffman WA, Nortje N (2015) Ethical misconduct by registered physiotherapists in South Africa (2007-2013): a mixed methods approach. South African J Physiother 71(1): 7.

- David TJ, Bray SA, Farrell AM, Allen N, Ellson S (2009) Fitness to practise procedures for undergraduate healthcare students. Education Law J 10(3): 102-112.

- R (on the application of Ngole) v University of Sheffield and Health and Care Professions Council (2017) EWHC 2669 (Admin).

- Cross V (1998) Begging to differ? Clinicians@ and academics’ views on desirable attributes for physiotherapy students on clinical placement. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Educ 23(3): 295-311.

- Grace S, Trede F (2013) Developing professionalism in physiotherapy and dietetics students in professional entry courses. Studies in Higher Educ 38(6): 793-806.

- Hilton SR, Slotnick HB (2005) Proto-professionalism: how professionalization occurs across the continuum of medical education. Medical Educ 39(1): 58-65.

- Jha V, Bekker HL, Duffy SR, Roberts TE (2007) A systematic review of studies assessing and facilitating attitudes towards professionalism in medicine. Medical Educ 41(8): 822-829.

- Lynch DC, Surdyk PM, Eiser AR (2004) Assessing professionalism: a review of the literature. Med Teacher 26(4): 366-373.

- Arnold L (2002) Assessing professional behaviour: yesterday, today and tomorrow. Acad Med 77(6): 502-515.

- Jette DU, Portney LG (2003) Construct validation of a model for professional behavior in physical therapist students. Phys Ther. 83(5): 432-443.

- Lo K, Curtis H, Keating JL, Bearman M (2017) Physiotherapy clinical educators’ perceptions of student fitness to practise. BMC Medical Educ 17: 16.

- Papadakis MA, Hodgson CS, Teherani A, Kohatsu ND (2004) Unprofessional behavior in medical school is associated with subsequent disciplinary action by a state medical board. Acad Med 79(3): 244-249.

- Papadakis MA, Teherani A, Banach MA, Knettler TR, Rattner SL, et al. (2005) Disciplinary action by medical boards and prior behavior in medical school. N Engl J Med 353(25): 2673-2682.

- Boak G, Mitchell L, Moore D (2012) Student fitness to practise and student registration. A literature review. Health and Care Professions Council, London.