The Mindful Pause: Cultivating Emotional Balance through Mindfulness (CEBtM)

Radhule Weininger1*, Sean Patrick Hatt2, Shauna Shapiro3 and Anahita Navab Holden4

1Clinical Psychologist, USA

2Seattle Integrative Psychology, USA

3Associate Professor of Counseling Psychology, Santa Clara University, USA

4MacVeagh House, USA

Submission: November 13, 2017; Published: December 13, 2017

*Corresponding author: Radhule Weininger, Clinical Psychologist, MacVeagh House, 2565 Puesta del Sol, Santa Barbara, CA 93105, USA, Tel: 805-569-5408; Email:radhule@gmail.com

How to cite this article: Radhule W, Sean P H, Shauna S, Anahita N H. The Mindful Pause: Cultivating Emotional Balance through Mindfulness (CEBtM). J Yoga & Physio. 2017; 3(4): 555616. DOI: 10.19080/JYP.2017.03.555616.

Abstract

The Buddhist technique of mindfulness has become widespread in clinical practice as a way to approach mental and emotional well-being. The mindful pause is described as a way to interrupt habitual reactivity and engage compassionately with oneself and others in everyday interactions and activities. It forms the foundation for both the Emotional Awareness Process (EAP) and the Compassionate Choice Process (CCP), which have been developed as therapeutic techniques grounded in both Buddhist and neuroscientific contexts. Two case examples of application of the processes illustrate how these new therapeutic interventions may prove to be beneficial in clinical practice. Lastly, more potential applications are proposed, with possible limitations, future projects and research noted.

Keywords: Mindfulness; Buddhist philosophy; Buddhist psychology; Neuroscience

Introduction

The history of clinical psychology examining the intersection of Eastern and Western approaches to mental and emotional well being is lengthy [1]. The use of the Buddhist practice known as mindfulness, or the nonjudgmental awareness of one’s internal and external landscapes moment by moment, serving as the foundation of a host of manualized, secularized practices, has exploded in the clinical mainstream over the past three decades, led by the ground breaking work of Jon Kabat-Zinn at the University of Massachusetts and his system called Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) [2,3]. More recently, mindfulness-informed psychotherapies, wherein Buddhist wisdom and philosophy are integrated into the therapist’s theoretical orientations without ever explicitly teaching any meditative skills have also become commonplace in the clinical lexicon [4]. In combination with the groundbreaking work in a multi-disciplinary field known as social neuroscience [5], in particular, the attachment-based field of interpersonal neurobiology [6,7], the importance of the mindful therapist’s quality of presence has also come to the fore [4,8].

The purpose of this paper is to add to the important body of literature at the crossroads of the spiritual, secular and clinical through introducing a mindfulness-based approach to cultivating emotional balance called the Emotional Awareness Process (EAP) and the Compassionate Choice Process (CCP). This paper describes how the EAP and the CCP are grounded as tools in both Buddhist and neuro-scientific contexts. It then presents the tools used in clinical practice to guide use of the EAP and CCP alongside two clinical vignettes to illustrate its utility. Lastly, the paper sets out speculation about the promise of the EAP and CCP in clinical and research settings and how future research could move beyond the level of clinical anecdote.

Theoretical Foundationt

The EAP and CCP have theoretical roots in the perennial wisdom of Buddhist philosophy and psychology while also drawing on current Western scientific research [9]. In developing the EAP and CCP, Eastern and Western insights and practices were integrated to foster the development of well-being, emotion regulation, self-awareness and empathy for self and other. Further, the EAP and CCP focus on emotional processes, mindfulness and compassion in an attempt to cultivate emotional balance [10].

A quest for mental balance

Wallace & Shapiro [11] describe mental balance as having four aspects: attentional, cognitive, affective, and conative. In order to experience balance across this broader range, one first needs to have attentional balance, or the ability to calm and focus one’s mind to witness one’s thinking with clarity and increased awareness. Cognitive balance is achieved when a mind is neither restless nor drowsy, but rather simultaneously relaxed and alert. Affective balance refers to the capacity to recognize and regulate emotions. Finally, conative balance signifies the intention or desire to live within a value system that is based on wisdom, compassion and ethical conduct.

Balancing these four elements may lead to a state of eudemonia, or a sense of deep well-being that does not originate from outside pleasurable stimuli, acquisitions, achievements or people, but rather from the capacity to be happy with oneself. Having cultivated this inner happiness, a person might enjoy outside pleasurable stimuli or people even more, and in addition may become more resilient to stress [11].

Similarly, Walsh & Shapiro [11] found that mindfulness of emotional processes has a positive effect on well-being, including anxiety reduction, openness to experience and increased emotional stability. Emotional regulation is facilitated through the process of re-perceiving, which is described as a rotation of consciousness where what was previously perceived as subject becomes object: Re-perceiving facilitates this capacity to observe one’s mental commentary about experiences encountered in life. It enables us to see the present situation as it is in this moment and respond accordingly, instead of with reactionary thoughts, emotions, and behaviors triggered by prior habit, conditioning and experience [12]. The EAP and CCP rest on the foundational principle that training in mindfulness and developing compassion for self and others make it possible to experience more freedom and happiness, and less suffering, anguish, anxiety and depression. The essence of such training focuses upon our capacity to mindfully and compassionately respond to circumstances in life rather than reacting mindlessly of our own emotional processes and how they tend to manifest behaviorally [11]. Like other clinical tools and systems informed by Buddhist philosophies and practices, the EAP employs mindfulness as its foundation. Mindfulness is defined by Shapiro & Carlson [4] as “awareness that arises through intentionally paying attention in a kind, open and discerning way."

Formal and informal mindfulness practice

Mindfulness can be cultivated through formal practices while sitting on a meditation cushion, as well as informal or “off the cushion" practices like mindful walking, mindful eating, or even doing the laundry. While the EAP and CCP are best understood as an informal practice, it is useful to examine formal practices as well in order to understand better the foundational skills involved with the EAP and CCP to lay the groundwork for discussion of what sort of training might be required of competent EAP and CCP clinicians.

Formal practice

When practicing mindfulness formally, the practitioner remembers to maintain attention upon the chosen object, for example, the sensation of the breath. In so doing, the meditator learns to maintain moment-to-moment awareness to present events [13].

The development of mindfulness results in learning to witness the phenomena of body and mind with tranquil clarity rather than being swept up and overwhelmed by sensations or thoughts. This increases one’s capacity to relate to others and the world with heightened awareness and in a sensitive, skillful and stable way. Mindfulness might best be thought of as the gateway to the present moment, or a fulcrum balancing what is commonly experienced as a constant timeline of worry about both the past and future. The present moment may be seen as a kind of refuge connecting one with the “field of awareness" [14], or, as the Dalai Lama refers to it, “the field of benevolence" [15], which is timeless, formless and ultimately balanced. Connecting with this field regularly through regular formal meditative practice cultivates emotional stability, and enhances the capacity to respond rather than to react to life’s challenges [16].

Formal training in mindfulness typically focuses on cultivating three awareness skills: focusing, noticing and expanding [17]. One learns focusing through the practice of Shamata, which in Sanskrit means meditative quiescence, and which can be learned through mindfulness-of-breathing meditation [16]. The skill of noticing is honed in the practice of Vipassana, defined in Sanskrit as “insight into the nature of reality" [18], whereby one pays non-judgmental attention to the phenomena of the mind such as feelings, thoughts, memories, and images. By witnessing how these experiences arise, abide, and pass away, without grasping for them or pushing them away, the meditator learns to see clearly the ever-changing nature of phenomena. Sometimes the naming of the passing objects helps to steady the mind further [19]. Through Vipassana, one learns to see and gain insight into the state of one’s own mind and heart and the universal reality of change and interconnectedness [14]. The skill of expanding, or cultivating meta-awareness, is a cognitive stance that permits us to enlarge our awareness in two ways: When going inward, mindfulness connects us to the field of awareness, while going outward allows us to simultaneously be aware of our own subjective experience as well as the needs of our environment [20]. With practice, one develops the capacity to monitor the quality of both our attention and our interactions with others and the environment. This is ultimately what frees the mindful person from careening blindly down the road of habitual reactivity.

The practice ofmindfulness is best combined with the practice of loving kindness and compassion meditation as mindfulness is primarily a wisdom practice, whereas loving kindness and compassion is primarily a heart practice. Loving kindness and compassion, are positive qualities we all have within our basic nature. These positive qualities can be cultivated and thus enhanced. The effects of cultivation of kindness and compassion can with practice be patterned into our personality. It has been even found that changes in our neurophysiology can result from relatively short compassion training. Such a practice alters a person’s capacity for altruism and neural responses to suffering [21]. This ongoing practice of mindfulness and loving kindness as well as compassion practice together with the application of responding mindfully versus reacting during stressful situations shows promising results in clinical practice. In the relaxed, opened-up state, which we cultivate through regular mindfulness meditation, the cultivation of the heart practices, such as kindness and compassion is especially effective. A sense of caring and tenderness towards oneself and others can be enhanced. With ongoing practice, these attributes can become patterned into our personality, so they can arise spontaneously in a given situation. [22-24].

Informal practice

Weininger developed the EAP and the CCP tool to help her clients to apply skills based on the practice of mindfulness while in the midst of the challenging moments of their everyday lives or learning about what happened during a reactive episode when viewing such an event in hindsight. Weininger hypothesized that coming to understand in hindsight how mental balance could have been maintained or restored during a reactive episode would help individuals to eventually cultivate increasingly skillful patterns of responding to stressful situations.

The EAP tool helps the client step-by-step to raise her physical, emotional and mental awareness in an in-depth fashion. When following the reactive pathway the client can recognize what could happen when following the impulse to act out or in. It can be also extremely valuable to understand in hindsight the dynamics of a stressful impasse. When following the mindful pathway, the client can realize the possibilities that could open up when following a mindful course. The CCP shortens this process, making it more “user-friendly" when employed during a time of upset. Most people are able to view the reactive pathway only in hindsight. The authors wanted to allow for more immediacy around the time of being triggered. Therefore, we decided to create a shorter checklist centered on the mindful pause in the middle phase of the steps to engage compassionate awareness during the time of triggering. We propose then to immediately and uninterruptedly engage in a mindful and compassionate choice process. In the CCP the emphasis is on expanding compassionate awareness to ourselves as well as others, and thus introducing a wider, more caring perspective.

The EAP tool

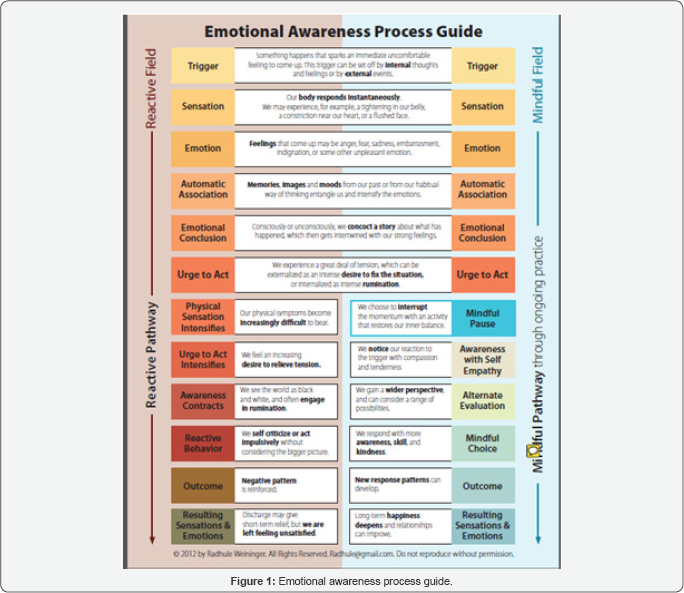

In Figure 1, the left side of the EAP diagram illustrates the reactive pathway, while the right side represents its alternative, the mindful pathway. Both pathways are set against a background of either the reactive or the mindful field. The reader is invited to think of both pathways as overlaying the background fields. We are more likely to be stuck in the reactive field at times of physical or emotional stress or exhaustion, or when reactivity and an absence of conative balance are supported by the culture around us. When we are situated in the reactive field and encounter a trigger event, we are likely to act in kind. In contrast, the mindful field is something we learn to cultivate through practices including mindfulness meditation, alongside practices that specifically aid in the cultivation of kindness, compassion, empathy and equanimity. Ongoing practice can strengthen the development of a mindful versus reactive field. Fortunately, the same principles apply to the mindful field as previously explained regarding the reactive environment. Thus, a mindful, non-anxious presence may be just as contagious as distress.

Common grounding in the feeling brain

Both pathways share their origin in the unity of body and mind. A triggering event leads seemingly instantaneously to sensations in the body. These physical experiences, such as a tightened belly or chest, or a flushing face, lead to emotional feelings and their automatic associated thoughts. While this appears to be linear, Damasio [25] suggests in his work on “the feeling brain" that it is more complex and co-creative, and defines a feeling in terms of “the perception of a certain state of the body, along with the perception of a certain mode of thinking and of thoughts with certain themes" (p. 86). We then make our automatic associations based upon memories, images and mood from our past, or from our habitual ways of being. Often, this leads to a felt sense of being entangled by our experience, which may serve to intensify our emotional state. Next, we leap to an emotional conclusion, concocting a story about what this whole experience means. This is followed by an urge to act in order to relieve the building tension in body and mind. We may have a desire to remedy a situation, to discharge our anxiety, or act out in anger. Or we may just turn the tension inward and engage in some form of intense rumination or worry. Paul Ekman refers to this sequence of perceptions as the “refractory period” [10], which occurs prior to reactive behaviors which may lead to undesirable outcomes.

The reactive pathway

The urge to act stage in the EAP diagram (Figure 1) is where the two pathways diverge. In the reactive pathway, the urge to act may lead to intensified physical sensations and an appraisal of the situation as intolerable. Thus, we may begin to feel an increased sense of urgency to act, and with that, our awareness may tend to contract around what suddenly appears to be a seemingly binary or “black and white” choice. The pathway culminates with engaging in what might best be understood as a default behavior, or a habitual reactive response, along with resultant short-term relief of anxiety. However, predictably negative consequences quickly give way to self-critical, remorseful and generally unhappy feelings.

It is the relief of anxiety and tension that creates a major psychobiological barrier to change. The release experienced either by acting out or acting in serves as a powerful reinforcement for the negative behavior. Acting out provides a surge of adrenalin and often makes the person feel more powerful and in control in the short run. Acting in can lead to a kind of infantile regression, which may be experienced as gratifying in the short-term, or to self-chastising or self-criticism, which may give us a sense of penance, or even purification.

The mindful pathway

The right side of the chart illustrates a contrasting possibility, the mindful pathway, which infuses the triggered internal landscape with awareness, compassion and choice. Initially, one may only be able to see what has happened in hindsight. This may bring increased self-awareness, but may also result in internalized shame and self-hatred or self-judgment. Thus, hindsight provides an important opportunity to develop and practice self-compassion as well as compassion for others.

Compassion researcher Kristin Neff [26] asserts that mindfulness involves turning toward our painful thoughts and emotions and seeing them as they are - without suppression or avoidance. As it is often difficult to view ourselves so precisely and honestly, it is helpful to embrace self-compassion, or “compassion turned inward” and a mutual interaction of “kindness, a sense of common humanity, and mindfulness” [27]. Germer & Neff [27] go on to report that self-compassion appears to support the development of resilience as it moderates reactions to negatively perceived events. This includes a lessening of reaction intensity, fewer negative emotions, an increase in acceptance and a greater likelihood that problems will be perceived with a broader sense of perspective as well as increased personal responsibility.

The role of the mindful pause

Helping the client to recognize that they are in a reactive state opens the door to a mindful pause, wherein the client might use the skills of mindfulness and compassion to interrupt the habitual chain of thoughts, feelings and behaviors. Noticing and appreciating reactions to triggering events with curiosity and compassion may lead to gentle inquiry, which in turn opens the door for alternative evaluations of the same situation. From a place of possibility and compassion as opposed to a collapse into binary reactivity, clients may find themselves free to make mindful choices with awareness, skill and kindness, thus allowing for new outcomes, which may in turn be reinforced by long-term benefit.

Confronting Challenges in the Early Stages of EAP Training

In order to help a client to cultivate self-compassion, particularly early in the process of learning to use the EAP, it may serve clinicians to help them understand their reactivity through a psychodynamic lens, in terms of deeply engrained, old and painful patterns [14,28]. Analytic adherents have referred to such patterns in a variety of ways, including complexes, or Painfully Recurring Patterns (PRPs). These are understood to be deep-seated, repetitive and hurtful formations of behavior, thought and feeling that intrude into one’s life over and over again when triggered by a suitable event. Often these patterns have their origin in acute or chronic trauma [29]. Helping a client to become mindfully and compassionately aware of the existence of such patterns may help to normalize them, making them potentially more understandable and manageable.

Clinicians may also find that clients encounter difficulties with the EAP in the here and now, as opposed to working with it in retrospect. In these instances, they may benefit from imaginatively recounting or rehearsing what it would have been like to initiate a mindful pause, and to include how they imagine it might have felt to treat themselves with tenderness while gaining a wider perspective and making a mindful choice. Such an exercise also expands the repertoire of possible perspectives and thus responses. This approach is supported by clinical research regarding imaginary rehearsal, in which imaginary sequences are shown to improve motor functioning [30] as well as the development of additional neurophysiological structures [31].

Case example 1

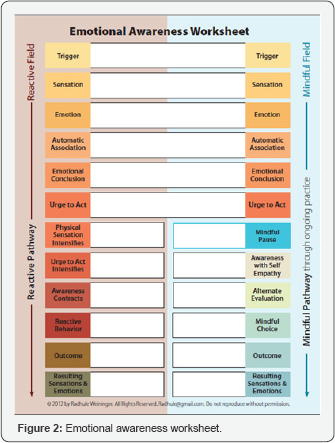

This case introduces the EAP Worksheet (Figure 2) and its use as a tool to help the client (or student of mindfulness) to learn to take a mindful pause and achieve mental balance in the face of disturbing or triggering circumstances. Its completion by the client or student facilitates the development of mindfulness in difficult situations in a way that is transparent to herself as well as her therapist, supervisor or teacher. Here, we elucidate the workings of the EAP Guide using the EAP Worksheet with the help of a clinical vignette. Details of the individual and their life have been changed in order to protect the identity of the client and people around them [32].

George is a 31 year-old male Asian American. He is a medical resident, concurrently serving in a research role at a university. He has a wife and two young children and is the sole breadwinner in his family. Recently under pressure to find a permanent job, George has been in discussions with a potential employer, and is suffering from anxiety, agitation and dysthymic mood as a result of these conversations. He is seeking relief from feeling “so stressed out and angry all the time.” Following an intake and 15 sessions to train in the basic skills of mindfulness meditation, self-compassion, and the use of the EAP, George presents his first completed EAP Worksheet.

Left side of the worksheet

Trigger: A trigger is an internal or external event that often sets off a cascade of sensory, emotional and cognitive experiences and behavioral reactions. George reported that he was triggered when this possible employer ended a recent phone conversation with George in a way that George interpreted as “abruptly.”

Sensations: Tactile sensations are a person’s pathway to the present moment and signify the impact the event has on the person. During and immediately after the phone call, George reported experiencing tension in his neck and shoulders. He also experienced a knot in his stomach and was not able to sleep that night.

Emotions: Emotions are often experienced together, or in close time connection with physical sensations and thoughts, as previously discussed. Sensations and emotions together bring intensity to experience. George described that he felt extraordinarily anxious and worried about his future. He feared that he was not going to get the job.

Automatic associations: Automatic associations are involuntary, and show up as memories, images or habitual ways of experiencing. These associations serve to heighten and seemingly entangle a person in their emotional state. George’s experience has become more complicated as a barrage of images and memories followed. He reported feeling haunted by memories of his stepfather criticizing, ridiculing and putting him down. The stepfather scared George frequently in his youth, and George still dreads interacting with him, even as an accomplished new physician and research scientist in a prestigious university. The therapist recognized a marker here for emotion-focused psycho-dynamically-informed psychotherapy to help George resolve some of this unfinished business with his family of origin.

Emotional conclusion: During the process of emotional conclusion, a person’s emotions and feelings are joined in the unconscious. Without being aware of what he was doing, George unknowingly began labeling himself in a detrimental way-as a failure. In George’s mind, the conversation was evaluated in absolute terms as a failure, which led to the false conclusion that he is neither good enough for this or any other job, nor is he adequate as a father, husband or son.

Urge to act: From this false emotional conclusion, an urge to act arose, a desire to fix the situation and relieve tension by doing something, internally or externally. In response to this negative self appraisal, George felt compelled to write e-mails to Dr. R., some of which were angry, chiding his potential new boss for being so rude and issuing a pre-emptive refusal of further consideration. Other fantasized correspondence sought more positive feedback in a passive way. Further, George also felt paralyzed by his fear, and had to fight an urge to hide in bed to ruminate about his imperfections and all of the possibly negative fallout of this failure.

Intensification of sensation and emotion: At this point things often get worse: On the reactive pathway, physical sensations intensify and are often experienced as intolerable. George reported bouts of diarrhea, further inability to sleep, and a feeling of wanting to crawl out of his skin, especially during the early morning hours.

Awareness contracts: Under this kind of pressure, awareness tends to contract, as things are often seen in black and white terms. George reported that things appeared totally hopeless. He labeled all of his conversations with the potential employer as complete failures.

Reactive behavior: Reactive behavior often occurs, where the person acts without forethought. The mounting internal pressure makes it impossible for him to hold in his frustrations any longer. George acted out in a limited way, send two anxious e-mails on to his future employer, but imagining sending several more insecure e-mails to his possible future employer, while he acted in by continuously ruminating about his shortcomings and all of the disasters that were to come.

Outcome: In engaging the reactive pathway, negative patterns are reinforced and resulting sensations and emotions are often distressing. If the client or student does act out, the temporary relief from anxiety has reinforced the pattern, while the self-punishment and other negative outcomes feed a positive feedback loop, keeping the client or student mired in anxiety and despair. In George’s case, he was deeply distressed by how events unfolded, which to him held a variety of frightening similarities to past scenarios. In the aftermath, George experienced more fear and anxiety, and a feeling of being controlled by outside forces. His anxiety took on more and more depressed features.

Mindful Pathway: Right Side of the EAP

Now, coached in the psychotherapy session using the EAP worksheet, George considers the right side of the worksheet with the intention of creating an alternative pathway. As he fills out the right side of the worksheet, he manages to infuse the reactive pathway with more awareness and becomes aware of the possibility of a different choice.

Mindful pause

On the right side of the chart, the initial steps are the same, beginning with the “trigger” through the “urge to act.” The difference is that there is now the possibility of awareness, facilitated by what we call the “mindful pause.” A Mindful Pause increases an individual’s capacity to step of the chain of reactivity. There are a number of necessary conditions for this to happen. The first of these is that the individual must recognize what is happening. This implies an awareness of the reactive chain of events. Another aspect of this awareness is the capacity to choose, to step out of the reactive chain by initiating what we call the Mindful Pause. The condition, however, is that they engage in what they choose mindfully. By having a background state that of calm, clear-mindedness and presence, we can choose how we proceed mindfully. George’s envisions his Mindful Pause as a decision to take a few hours off during the next afternoon. He wants to stop making things worse with his reactivity and insecurity. He puts his little daughter into a stroller and goes for a mindful walk. Feeling the sensations of the soles of his feet, he grounds himself in the experience of the present moment. He then meditates for half an hour with help of a guided mindfulness-of-breathing CD. Now much more calm, collected, and clear-headed by now, he finishes his mindful pause with some self-reflection through journaling. Through this mindfulness enhancing process, George was ready to proceed calmly and skillfully. On another day, however, when a similar impasse occurred during a stressful meeting, George was not able to take such an extended time to re-center himself. Instead, he excused himself to go to the bathroom. He went down the corridors of the building slowly and mindfully, stopped to look out the window to see the sun reflected on the leaves of a tree. While in the bathroom, he was especially attentive to the sensations in his body, especially to breath. When he returned to the meeting, he felt more calm and clear headed within himself.

Awareness with self-empathy

One is now able to notice internal experiences with self-empathy. George is now able to be aware of what is going on, and to see his thoughts and feelings with self-empathy. The insight gained by examining the automatic association with memories of feeling deeply frightened by his father’s ridicule and anger helps him to feel more understanding and tenderness towards himself. As George continues to feel kinder towards himself, he is able to relax and see things in a more differentiated and hopeful way.

Alternative evaluation

Feeling less fearful and constricted, one can hold a wider perspective. Thus, one can evaluate the situation anew. George realizes that there might have been many other possibilities for Dr. R.’s abrupt interruption of the phone call. George ponders “Maybe his wife wanted to go out for dinner, it was Friday at 5pm after all!”

Mindful choice

With more awareness and skill, one then can respond differently, which might include skillful action or, alternatively, a wise discernment to abstain from reactive behavior. George’s “alternative action” includes stopping the “acting in” -the constant self- punitive rumination. With more awareness, skill and self-confidence, George is now able to maneuver the discussions that follow, successfully leading to his future employment.

Outcome

With ongoing practice new habits can develop. The outcome is a successful move of the young family to the new place of work, and George’s continuing steps toward forming of new, mindful habits.

Resulting emotions and sensations

Long- term happiness deepens and is strengthened. George feels stronger and more settled in himself. Over time, he has far fewer periods of anxiety. With a continuous practice of regular exercise, meditation and occasional meetings with his psychotherapist, he is able to prevent future episodes of entrenched anxiety and depression. When occasional challenges come up, lighter periods with anxious feelings pass quickly. By using the EAP Guide, George was able to track where triggers would occur, condition himself to take a mindful pause and become more responsive rather than reactive in life. Using the EAP guide, George learned to bring mindfulness to those difficult moments. This in turn helped to bring awareness to the process of getting triggered. Even when one looks in hindsight at unfortunate events, awareness opens up situations and introduces the possibility of choice and change and eventually the creation of new habitual pathways, even neural pathways [7].

George’s story portrays a person, who turns his frustration and anxiety inwards. He “acts in” by way of rumination and self-blaming, which leads to his mental and physical symptoms. Other individuals tend to turn their frustrations and compulsions outward. These acts of “acting out” may include angry outbursts, impulsivity or addictive behavior. Subsequently we will introduce the Compassionate Choice Process, which can be especially useful around the time of being triggered.

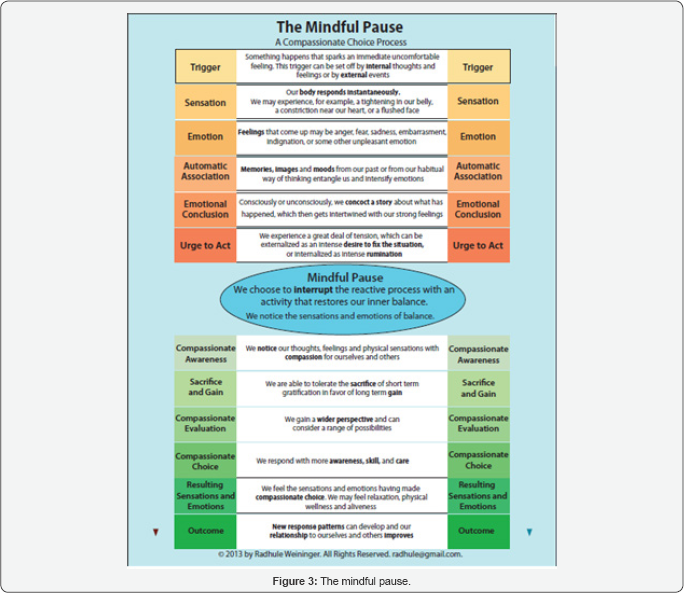

The Mindful Pause as Part of the Compassionate Choice Process

The CCP serves as an additional “self-help” tool, one, which can be especially useful around the time of being triggered, helping clients learn to respond mindfully, compassionately and thoughtfully. The related chart is streamlined, designed for use around a time of upset Figure 3. The first six of the 12 boxes describe internal events that follow triggering. The mindful pause occurs in the middle of the process, indicated on the chart by a metaphorical pause “button” that can be consciously pressed. Progress through the steps helps to achieve an observational and re-balanced stance, which helps to re-stabilize the mind. The mindful pause assists in developing increased self-awareness, inner steadiness and focus in the midst of being thrown off balance, infusing compassionate awareness into a cascade of internal and external events.

Case example 2

Susan is a 56 year old elementary school teacher who has lived alone with her cat since her 19 year old daughter left for college. She saved money during the past year to be able to go to a continuing edication conference. Even though Susan had been looking forward to this conference, hoping this would open new professional and personal opportunities, some of her old timidity resurfaced during this week. On the second day, a PRP was triggered in the early morning. When approaching a seat in the conference center that she had claimed on the first day, she noticed that another woman, Emma, had taken her place and moved Susan’s belongings aside.

Suan felt a jolt in her body. Her chest tightened and her fists clammed together. She felt a mixture of rage and great anxiety. Memories rose up of herself as a little girl, feeling so often like the peculiar outsider. As one of her automatic associations, she remembered being mocked by classmates. The automatic emotional conclusion to this event left her feeling like she “was not worth anything” and that “nobody liked and respected” her. Her urge to act in order to fix this dismal situation was to either pack her bags and leave, or to approach the woman, who had “stolen” her chair, and to confront her. She wanted literally to set her in her place. At the same time Susan felt embarrassed by her own reactivity. She felt a great longing to be free from this old childhood pattern of feeling “left out.” As she knew the CCP process, she remembered to take a mindful pause. She went to the hotel’s swimming pool where she swam mindfully, allowing her mind to clear. After about and a half hour, she was able to notice her feelings, thoughts, and body sensations with much more clarity and self-compassion. She experienced empathy for herself after the many hurts and setbacks she had experienced in her life. She also felt some concern and warmth for the other woman, the one who had “stolen” her place. Emma was quite a bit older and much more fragile than Susan. Susan pondered, “Maybe Emma had not been able to see or hear well from a chair further away.” After considering Emma’s situation she felt less aggravated. She was able to bear the short term sacrifice of not “expressing what she felt” towards Emm, andable to stay aware of the long term gains of not following her urge to be reactive; she could complete the course, and feel much more empowered than victimized. Following a “compassionate evaluation” of herself and the overall situation, she could hold a wider perspective and allow herself simply to let the difficult situation pass. Susan ended up finding another chair close by, and happy that she had found a workable compromise without letting the situation turn ugly. The long-term outcome was increased insight into her triggers and confidence that she could solve problems without ending up feeling like a victim or an oppressor. She gained the confidence that she could slowly and surely change her default pattern of feeling like an outsider.

Susan’s story shows how awareness of one’s internal processes helps to slow down and bring awareness to what is going on inside. One can then choose to interrupt a habit of reactivity and gain greater emotional balance and control. From this point of view one is able to make wiser, more mindful and compassionate choices, which ultimately lead to more successful outcomes.

Conclusion

This paper proposes that the clinical application of a complementary approach of Buddhist and Western methods of self-awareness and self-empathy may have a positive treatment outcome for clients suffering from emotional imbalance and reactivity and even long-standing psychological patterns, which when triggered cause considerable mental and emotional anguish. A move from the reactive pathway to a responsive pathway characterized by more choice is facilitated by the degree of mindfulness or self-awareness that the individual has cultivated. The EAP and the CCP comprise two different versions of this process. The EAP permits us to explore in depth what would have happened or what did happen, as we allow ourselves to engage in a reactive pathway and what happens when we bring mindfulness and self-empathy to the situation that challenged us. Choosing to interrupt an upsetting process and rebalancing oneself before a situation, becomes harmful is facilitated by choosing to take a mindful pause, which furthers self-empathy, awareness and choice, and leads to better short-term outcomes and the development of healthier long-term patterns. This process can easily be used within a therapy situation, and can provide clarity and depth concerning a reactive dynamic. By lending words to explore and describe what happened, our understanding can lead to compassion. With the CCP, the process is adjusted and streamlined to be useful during or around the time when a person is triggered. The Mindful Pause is emphasized here, and more importance is given to holding compassion alongside mindfulness. The additional step of bringing awareness to the short-term sacrifice involved in not acting out or in and the long-term gain of avoiding conflict helps to develop a new and healthy pattern of response to triggers. This step might be especially useful when a person is struggling with addiction in that the emphasis on compassion may allow an individual to tolerate her own struggles and may motivate further introspection and research. An ongoing practice of mindfulness meditation is recommended as a way of enhancing self-awareness.

Loving kindness and compassion practices are also suggested in order to develop kindness, compassion, empathy and equanimity for self and other. Currently, the authors are teaching the use of the EAP in academic settings, including a clinical psychology PhD program and a variety of clinical settings focused on the treatment of individuals with OCD, including excessive rumination, depression, anxiety, impulse control problems and relationship problems. The related skills were also taught as CEBtM during a six weekend-day class on Buddhist and Western psychological principles, the EAP, journaling and meditation training.

Further, the EAP was used with University students at a counseling center, in a jail setting, with juvenile delinquents, with women and children suffering from PTSD due to physical and sexual abuse and with people suffering from eating disorders. The CEBtM has been also taught as a seven-week class within a psychology PhD program. In the coming year the CEBtM will be taught in a Community College setting as part of a training for Drug and Alcohol Counselors, teaching how to use the EAP and the CCP with people in recovery. Future plans to use the EAP and the CCP include integrating these processes into programs treating addictions, including eating disorders. The authors propose that the EAP and CCP could be very useful in parenting training, couple’ and family therapy as well as working with people suffering from a lack of impulse control such as OCD. Clients suffering from internalizing syndromes, anxiety and depression, including excessive rumination, may also be helped. In addition, the two processes could be very useful as a way to keep “field notes” for psychology students, nursing students and medical residents. In our small pilot program, the EAP process helped psychology interns to be aware of their transference and counter-transference reactions towards their clients and thus gain greater clarity and effectiveness with treatment planning and execution.

While anecdotal experience is encouraging, and suggests at least the feasibility of teaching the EAP and CCP, further study is needed. Qualitative and quantitative research would help more systematically to determine the benefits of the EAP and the CCP and to elucidate the best ways to implement this innovative intervention. There are limitations to the model, in that different age and ethnic groups may respond differently to the words chosen to explain the process. Younger clients might need fewer steps in the EAP and CCP process. Different clients might experience the proposed steps in a different sequence and find meaning in a mindful pause in different ways. Some clients might find meditation useful, others might prefer a walk in the woods, exercise in a Gym or simply a cup of tea. A mindful pause may be short or long, depending what is possible and practical for the client. We propose future phenomenological research to validate the essential structures of the process using existential phenomenological inquiry The EAP and CCP are being incorporated into an interactive website and smart phone application to guide an individual through the processes. The hope of this extension of the project is to make it even more “user-friendly” and easily accessible in a form where the client is able to use the processes independently.

The EAP and CCP provide simple and effective ways to respond mindfully to triggers that might otherwise evoke reactive and maladaptive emotional responses [10,15]. Though our observations are purely anecdotal, early results of using the EAP include greater awareness and mastery over actions, decreases in anxiety and depression and in problematic behaviors. We believe that these results arise from a new emotional baseline, fostered through EAP therapy, which enables clients to skillfully navigate the myriad challenges and complexities of daily existence. In addition to the help it can provide to clients, the EAP and CCP can also be seen as a way for therapists previously only “mindfully-informed” to become more practically “mindful” both personally and in their work.

References

- Semple RJ, Hatt SP (2011) Translation of Eastern meditative disciplines into Western psychotherapy. In: Miller LF (Ed.), Oxford Handbook of the Psychology of Religion and Spirituality. Oxford University Press, New York, USA, pp. 326-342.

- Zinn JK (1984) An outpatient program in behavioral medicine for chronic pain patients based on the practice of mindfulness meditation: theoretical considerations and preliminary results. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 4(1): 33-47.

- Zinn JK (1990) Full Catastrophe Living. Bantam Doubleday Dell, New York, USA.

- Shapiro S, Carlson L (2009) The art and science of mindfulness. The American Psychological Association, Washington, DC, USA.

- Cacioppo JT, Berntson GG (2004) Social neuroscience: Key readings. Psychology Press/Taylor & Francis Group, New York, USA.

- Siegel DJ (2007) The mindful brain: Reflection and attunement in the cultivation of well-being. Norton, New York, USA.

- Siegel DJ (2009) Mindful awareness, mindsight, and neural integration. The Humanistic Psychologist 37(2): 137-158.

- Siegel DJ (2010) The mindful therapist: A clinician’s guide to mindsight and neural integration. Norton, New York, USA.

- Ekman P (2007) Emotions revealed: Recognizing faces and feelings to improve communication and emotional life. Owl/Henry Holt and Company, New York, USA.

- Dalai Lama HH, Ekman P (2008) Emotional awareness: Overcoming the obstacles to psychological balance and compassion: A conversation between the Dalai Lama and Paul Ekman. Times Books/Henry Holt and Company, New York, USA.

- Wallace BA, Shapiro S (2006) Mental balance and well-being: Building bridges between Buddhism and Western psychology. Am Psychol 61(7): 690-701.

- Walsh R, Shapiro S (2006) The meeting of meditative disciplines and Western psychology. American Psychologist 61(3): 227-239.

- Zinn JK (1994) Wherever you go, there you are: Mindfulness meditation in everyday life. Hyperion, New York, USA, p. 278.

- kornfield J (2008) The wise heart: A guide to the universal teachings of Buddhist psychology. Random House, New York, USA.

- Goleman D (1988) The meditative mind: The varieties of meditative experience. Tarcher/Putnam Books, New York, USA.

- Wallace BA (2006) Genuine happiness: Meditation as the path to fulfillment. John Wiley, Hoboken, NJ, USA.

- Kearney M, Weininger R (2012) Care of the Soul. In: Cobb M, Puchalski C, Rumbold B (Eds.), Oxford Textbook of Spirituality in Healthcare. Oxford University Press, New York, USA, pp. 274-278.

- Rahula W (1959) What the Buddha taught. Grove Press, New York, USA.

- Zinn JK (2003) Coming to our senses: Healing ourselves and the world through mindfulness. Hyperion, New York, USA.

- Kearney M, Weininger R, Vachon M, Harrison R, Mount B (2009) Selfcare of physicians caring for patients at the end of life. JAMA 301(11): 1155-1164.

- Weng HY, Fox AS, Shackman AJ, Stodola DE, Caldwell JZK, et al. (2013) Compassion training alters altruism and the neural responses to suffering. Psychol Sci 24(7): 1171-1180.

- Klimecki O, Leiberg S, Lamm C, Singer T (2012) Functional neural plasticity and associated changes in positive affect after compassion training. Cerebral Cortex 23(7): 1552-1561.

- Lutz A, Lewis JB, Johnstone T, Davidson R (2008) Regulation of the Neural Circuitry of Emotion by Compassion Meditation: Effects of Meditative Expertise. PloS ONE 3(3): e1897.

- Kearney D, Malte C, McManus C, Martinez M, Felleman B, et al. (2013) Loving-Kindness Meditation for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A Pilot Study. J Trauma Stress 26(4): 426-434.

- Damasio A (2003) Looking for Spinoza: Joy, sorrow and the feeling brain. Harcourt, Orlando, FL, USA.

- Neff KD (2003) Self-compassion: an alternative conceptualization of a health attitude toward oneself. Self and Identity 2: 85-102.

- Germer C, Neff KD (2013) Self-compassion in clinical practice. J Clin Psychol 69(8): 856-867.

- Epstein M (1999) Going to pieces without falling apart: A Buddhist perspective on wholeness. Harper, New York, USA.

- Heim C, Nemeroff CB (2001) The role of childhood trauma in the neurobiology of mood and anxiety disorders: preclinical and clinical studies. Biological Psychiatry 49(12): 1023-1039.

- Holmes PS, Collins DJ (2001) The PETTLEP appproach to motor imagery. Journal of Applied Sports Psychology 13(1): 60-83.

- Moulder T (2007) Motor imagery and action observation: Cognitive tools for rehabilitiation. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 114(10): 1265-1278.

- Watson G (2008) Beyond happiness: Deepening the dialogue between Buddhism, psychotherapy, and the mind sciences. Karnac Books Ltd, London, UK.