Abstract

Redox-active metalloproteins regulate electron transport, ROS detoxification, and metal ion homeostasis, but their dysregulation contributes to oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and protein aggregation in neurodegenerative disorders like Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and ALS. Aberrant metal-protein interactions exacerbate disease progression, making them promising therapeutic targets. Strategies such as metal chelation, antioxidants, and nanotechnology-based drug delivery offer potential for mitigating neurotoxicity. This review highlights the pathological roles of metalloproteins and emerging approaches to restore redox balance and neuronal health.

Keywords: Redox-Active; Metalloprotein; Neurodegenerative disorder; Alzheimer Disease; Parkinson Disease; Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis; Neuronal health; Copper; Manganese; Mitochondrial respiration; Amyloid precursor protein; Cytochromes

Introduction

Neurodegenerative disorders (NDs) such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Parkinson’s disease (PD), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), and prion diseases represent a significant global health challenge due to their progressive nature and lack of effective curative treatments [1]. These disorders are characterized by the gradual loss of neuronal structure and function, ultimately leading to cognitive and motor impairments (Figure 1). Despite their distinct pathological features, a common hallmark of NDs is oxidative stress, which plays a crucial role in disease onset and progression [2]. Oxidative stress arises from an imbalance between the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and the ability of cellular antioxidant systems to neutralize them. Neurons, due to their high metabolic activity and oxygen consumption, are particularly vulnerable to oxidative damage. Excessive ROS can trigger lipid peroxidation, protein misfolding, mitochondrial dysfunction, and DNA damage, all of which contribute to neuronal degeneration [3,4]. A major source of ROS generation in the brain involves redox-active metalloproteins, which are proteins that utilize transition metal ions (such as iron (Fe), copper (Cu), and manganese (Mn)) as essential cofactors in biological redox reactions. These metalloproteins play vital roles in numerous physiological processes, including mitochondrial respiration, enzymatic catalysis, and antioxidant defense mechanisms [5]. Under normal conditions, their redox activities are tightly regulated to prevent excessive ROS formation. However, under pathological conditions, such as metal dyshomeostasis or protein misfolding, these proteins can become dysfunctional, leading to aberrant metal-catalyzed redox reactions and oxidative damage [6,7]. Recent investigations have established a critical role for redox-active metalloproteins in the pathophysiology of neurodegenerative disorders. For instance, mutations in superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) are implicated in the etiology of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) by facilitating aberrant protein aggregation and inducing oxidative cytotoxicity [8,9]. Likewise, dysregulation of iron-binding proteins, including ferritin and transferrin, contributes to pathological iron sequestration and oxidative burden in Parkinson’s disease (PD). Additionally, the amyloid precursor protein (APP), a key player in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) pathology, exhibits metal-binding properties that potentiate reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation and promote amyloid fibrillogenesis. Given their integral role in maintaining redox equilibrium and their involvement in disease-associated oxidative dysregulation, redox-active metalloproteins have emerged as potential therapeutic targets in neurodegeneration [10-12].

Redox-Active Metalloprotein: Classification & Mechanism

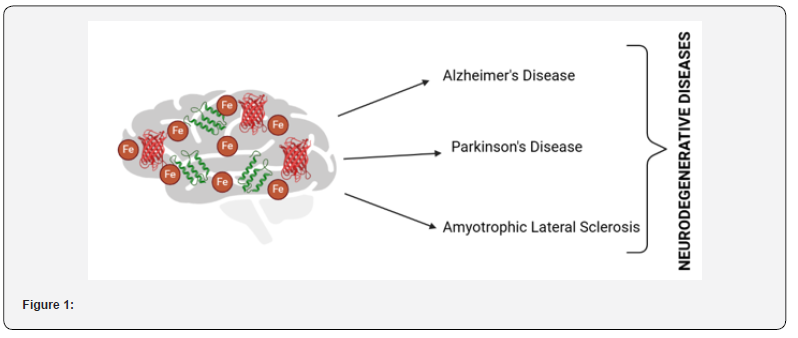

Redox-active metalloproteins are specialized proteins that utilize transition metal ions as cofactors to mediate electron transfer reactions essential for maintaining redox balance in biological systems. These proteins are integral to numerous physiological processes, including mitochondrial respiration, oxidative stress response, enzymatic catalysis, and metal ion transport. Their ability to undergo reversible oxidation and reduction enables them to participate in vital biochemical pathways such as ATP production, free radical detoxification, and iron homeostasis. However, dysregulation of these proteins or disruptions in metal ion equilibrium can lead to oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and neuronal damage, ultimately contributing to the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative disorders [13-17]. Redox-active metalloproteins mediate electron transfer reactions by cycling their metal cofactors between oxidized and reduced states, facilitating essential biological processes that maintain cellular homeostasis. A primary function of these proteins is their role in electron transport and ATP production, particularly within the mitochondrial respiratory chain, where ironcontaining cytochromes (e.g., Complexes I-IV) shuttle electrons to drive oxidative phosphorylation (Figure 2). Dysfunction of these cytochromes leads to mitochondrial impairment, ATP depletion, and excessive ROS production, which are hallmark pathological features of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Parkinson’s disease (PD), and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS).

Additionally, metalloproteins contribute to ROS detoxification, as copper- and manganese-dependent superoxide dismutases (SOD1, MnSOD) catalyze the dismutation of superoxide radicals into less reactive species, mitigating oxidative stress. Mutations in SOD1, particularly in ALS, lead to protein misfolding, toxic gainof- function, and neuronal degeneration, further exacerbating oxidative toxicity [18-23]. Furthermore, metalloproteins regulate iron and copper homeostasis through key proteins such as ferritin, transferrin, and ceruloplasmin, which are essential for maintaining metal ion storage, transport, and oxidation states. Dysregulation of these proteins results in iron overload, copper toxicity, and redox imbalance, which contribute to neurodegeneration in PD, AD, and prion diseases [24]. Another critical mechanism by which metalloproteins influence neurodegeneration is through metal-protein interactions and protein aggregation, as neurodegeneration-associated proteins such as amyloid precursor protein (APP), α-synuclein, and tau exhibit metal-binding properties25. Abnormal interactions with iron and copper ions enhance ROS production, protein aggregation, and neurotoxicity, thereby accelerating disease progression in AD and PD. Collectively, these dysregulated processes underscore the indispensable role of redox-active metalloproteins in oxidative stress regulation, mitochondrial dysfunction, and neurodegenerative pathogenesis [24-27].

Redox Dysregulation and Neurodegenerative Disease Pathogenesis

Redox homeostasis plays a crucial role in maintaining neuronal function and survival, as the brain is highly vulnerable to oxidative damage due to its high oxygen consumption, abundant lipid content, and relatively low antioxidant capacity [28]. Neurons rely heavily on redox-active metalloproteins to regulate electron transport, oxidative stress responses, and metal ion homeostasis. However, in neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Parkinson’s disease (PD), and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), dysregulation of these proteins leads to excessive oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, protein aggregation, and neurotoxicity, ultimately contributing to disease pathogenesis [29]. The imbalance between reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and antioxidant defense mechanisms in these conditions results in cellular damage that exacerbates neuronal death. One of the key features of redox dysregulation in neurodegenerative diseases is the abnormal accumulation and mismanagement of transition metals, particularly iron, copper, and zinc, in specific brain regions. These metals are essential cofactors for various redox-active enzymes but can become highly toxic when their homeostasis is disrupted. In AD, excessive iron accumulation in the hippocampus and cortex has been implicated in the formation of amyloid-beta (Aβ) plaques and tau hyperphosphorylation, two hallmark features of the disease. Iron interacts with Aβ peptides, catalyzing the production of hydroxyl radicals via Fenton chemistry, which enhances oxidative damage and promotes amyloid aggregation. Similarly, elevated copper and zinc levels further stabilize Aβ oligomers, exacerbating synaptic dysfunction and neuronal loss [30].

In PD, iron overload in the substantia nigra plays a major role in dopaminergic neurodegeneration. Iron interacts with α-synuclein, a key protein in PD pathogenesis, promoting its aggregation into Lewy bodies and further amplifying oxidative stress [31]. The iron-induced generation of ROS leads to lipid peroxidation, mitochondrial damage, and neuroinflammation, all of which contribute to dopaminergic neuronal loss. Additionally, dysregulated copper metabolism has been reported in PD, as evidenced by altered levels of ceruloplasmin, a copper-dependent ferroxidase involved in iron export [32] Impaired ceruloplasmin function leads to intracellular iron retention, creating a feedback loop of oxidative damage that worsens disease progression. In ALS, mutations in superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1), a copper- and zinc-dependent antioxidant enzyme, disrupt its ability to detoxify superoxide radicals, leading to the accumulation of toxic oxidative species. Misfolded SOD1 aggregates contribute to mitochondrial dysfunction, endoplasmic reticulum stress, and neuronal toxicity, exacerbating motor neuron degeneration [33]. Furthermore, copper dyshomeostasis has been identified in ALS, with studies showing decreased copper availability in SOD1 mutants, leading to a loss of enzymatic function and enhanced oxidative stress. The redistribution of copper from its normal cellular reservoirs further disrupts metal-dependent enzymatic processes, creating an environment that accelerates neurodegeneration [34].

Beyond metal dyshomeostasis, redox-active metalloproteins directly interact with misfolded and aggregated proteins, further propagating oxidative damage. In AD, amyloid precursor protein (APP) contains metal-binding domains that promote oxidative stress and Aβ oligomerization when interacting with iron or copper [35]. In PD, iron-bound α-synuclein adopts a toxic conformation that increases fibril formation and triggers neuroinflammatory responses, facilitating the spread of Lewy body pathology throughout the brain. Similarly, in prion diseases, the oxidation of prion protein (PrP) accelerates its misfolding into pathogenic isoforms, which disrupts neuronal function and increases oxidative burden. These interactions create a self-perpetuating cycle of protein aggregation and oxidative toxicity, amplifying disease severity [36]. Additionally, redox dysregulation exacerbates mitochondrial dysfunction, a common pathological feature in neurodegenerative diseases. Mitochondria are a primary source of ROS production due to their role in oxidative phosphorylation, and impairment of redox-active electron transport chain proteins (such as cytochromes and ironsulfur cluster proteins) results in electron leakage and increased oxidative damage [37]. In AD, mitochondrial dysfunction leads to energy deficits, synaptic failure, and neuronal apoptosis, while in PD, mitochondrial complex I inhibition contributes to dopaminergic neuronal degeneration. In ALS, oxidative stressinduced mitochondrial damage affects axonal transport and motor neuron viability, further accelerating disease progression [38].

Therapeutic Strategies Targeting Redox Dysregulation in Neurodegenerative Diseases

Considering the pivotal role of redox imbalance and metal dyshomeostasis in the development of neurodegenerative disorders, therapeutic strategies focused on restoring redox homeostasis, reducing oxidative stress, and regulating metalprotein interactions have garnered significant interest [39]. Various approaches, such as antioxidant therapy, metal chelation, metalloprotein-targeting drugs, and mitochondrial protection, are being investigated for their potential to slow or prevent neurodegeneration [40].

Antioxidant Therapies

One of the primary therapeutic strategies involves the use of antioxidants to neutralize reactive oxygen species (ROS) and prevent oxidative damage. Small-molecule antioxidants such as vitamin E, vitamin C, coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10), and N-acetylcysteine (NAC) have shown promise in reducing oxidative stress in preclinical and clinical studies [41-43]. Additionally, polyphenolic compounds such as resveratrol, curcumin, and epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) exhibit strong antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, with evidence suggesting their ability to scavenge ROS, regulate redox-active proteins, and inhibit neurotoxic protein aggregation. More recently, synthetic antioxidants like MitoQ and SS-31, which are specifically designed to target mitochondrial ROS, have emerged as potential neuroprotective agents, particularly in diseases where mitochondrial dysfunction plays a key role, such as Parkinson’s disease (PD) and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [41-45].

Metal Chelation Therapy

Since metal dyshomeostasis is a major contributor to oxidative stress and neurotoxicity, metal chelators have been investigated as potential therapeutic agents. Chelators such as deferiprone, clioquinol, and PBT2 have been designed to selectively bind excess iron or copper, thereby preventing their participation in Fenton chemistry-driven ROS production. Deferiprone, an FDA-approved iron chelator, has shown efficacy in reducing iron accumulation in the substantia nigra of PD patients, with potential benefits in slowing dopaminergic neuronal loss. Similarly, PBT2, a secondgeneration 8-hydroxyquinoline-based chelator, has demonstrated the ability to modulate copper and zinc interactions with amyloidbeta (Aβ), thereby reducing amyloid aggregation and oxidative stress in AD models [46]. However, challenges such as maintaining physiological metal homeostasis while preventing toxicity remain key hurdles for chelation-based therapies [47].

Modulating Redox-Active Metalloproteins

Targeting specific redox-active metalloproteins implicated in neurodegeneration has emerged as a promising approach. For instance, stabilizing superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) mutations in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) using copper chaperones or small molecules such as ebselen has been explored as a strategy to restore its enzymatic function and reduce oxidative damage [48]. Similarly, targeting ceruloplasmin and ferritin to normalize iron metabolism is being investigated as a therapeutic approach for PD and AD. Additionally, small molecules that prevent metal-induced protein aggregation, such as inhibitors of α-synuclein–iron interactions in PD or Aβ–copper interactions in AD, are currently under development [49].

Mitochondrial Protection and Bioenergetic Support

Since mitochondria play a central role in cellular redox balance and energy production, strategies aimed at protecting mitochondrial function are critical for combating neurodegeneration. Mitochondrial-targeted antioxidants (e.g., MitoQ, SS-31) and bioenergetic enhancers such as creatine, nicotinamide riboside (NR), and pyruvate are being investigated to improve ATP synthesis, reduce ROS leakage, and enhance neuronal resilience [50]. Moreover, mitophagy activators, which promote the selective degradation of damaged mitochondria, have gained interest as potential therapeutics to counteract mitochondrial dysfunction in neurodegenerative diseases [51].

Gene and Protein-Based Approaches

Advances in gene therapy and protein-based interventions have paved the way for novel therapeutic strategies targeting redox-active metalloproteins. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene editing holds potential for correcting mutations in SOD1 (ALS), APP (AD), and α-synuclein (PD), thereby preventing diseaseassociated protein misfolding and aggregation [52]. Additionally, monoclonal antibodies and small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) are being explored to selectively degrade toxic redox-active protein aggregates, such as Aβ plaques, tau tangles, and α-synuclein fibrils [53].

Conclusion

Redox-active metalloproteins play a fundamental role in maintaining neuronal homeostasis through their involvement in electron transport, ROS detoxification, and metal ion regulation. However, their dysregulation contributes to the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Parkinson’s disease (PD), and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) by exacerbating oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and protein aggregation. The intricate interplay between metal dyshomeostasis, oxidative damage, and neurotoxic protein accumulation underscores the complexity of these disorders and highlights the need for targeted therapeutic interventions. Although significant progress has been made in understanding the role of redox-active metalloproteins in neurodegeneration, many gaps in knowledge remain. Future research should focus on elucidating the precise molecular mechanisms underlying metalloprotein dysfunction, particularly in early-stage disease progression. Advancements in high-resolution imaging, proteomics, and metallomics could provide deeper insights into the spatiotemporal dynamics of metal-protein interactions in the brain, leading to the identification of novel biomarkers for early diagnosis. Therapeutically, while approaches such as antioxidant therapy, metal chelation, mitochondrial protection, and gene editing show promise, challenges related to drug specificity, blood-brain barrier (BBB) permeability, and potential off-target effects must be overcome. The development of nanotechnologybased drug delivery systems, biomimetic antioxidants, and metalloprotein-targeting small molecules could enhance treatment efficacy and safety. Additionally, personalized medicine approaches, incorporating genetic profiling and patient-specific biomarkers, may help tailor therapies to individual disease pathologies, improving clinical outcomes.

Conflict of Interest

None.

References

- K Acevedo, S Masaldan, CM Opazo, AI Bush (2019) Redox active metals in neurodegenerative diseases. JBIC Journal of Biological Inorganic Chemistry 24 (8): 1141-1157.

- G Goldsteins, V Hakosalo, M Jaronen, Keuters MH, Lehtonen Š, et al. (2022) CNS Redox Homeostasis and Dysfunction in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Antioxidants 11 (2): 405.

- H Gouri, G Bhalla (2025) Neurotoxic chemistry: Unraveling the chemical mechanisms connecting environmental toxin exposure to neurological disorders. Journal of Integrated Science and Technology 13(3): 1064.

- EO Olufunmilayo, MB Gerke-Duncan, RMD Holsinger (2023) Oxidative Stress and Antioxidants in Neurodegenerative Disorders. Antioxidants 12(2): 517.

- S Rivera-Mancía, I Pérez-Neri, C Ríos, Tristán-López L, Rivera-Espinosa L, et al. (2010) The transition metals copper and iron in neurodegenerative diseases. Chem Biol Interact 186 (2): 184-199.

- F Cardona (2024) Special Issue Mechanisms and Novel Therapeutic Approaches for Neurodegenerative Diseases. Biomedicines 12(11): 2554.

- Tarozzi A (2020) Oxidative Stress in Neurodegenerative Diseases: From Preclinical Studies to Clinical Applications. J Clin Med 9(4): 1223.

- M Berdyński, P Miszta, K Safranow, Andersen PM, Morita M, et al. (2022) SOD1 mutations associated with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis analysis of variant severity. Sci Rep 12(1): 103.

- I Sirangelo, C Iannuzzi (2017) The Role of Metal Binding in the Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis-Related Aggregation of Copper-Zinc Superoxide Dismutase. Molecules 22(9): 1429.

- MG Savelieff, G Nam, J Kang, Lee HJ, Lee M, et al. (2019) Development of Multifunctional Molecules as Potential Therapeutic Candidates for Alzheimer’s Disease, Parkinson’s Disease, and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis in the Last Decade. Chem Rev 119(2): 1221-1322.

- KM Kanninen, AR White (2017) Abnormal Function of Metalloproteins Underlies Most Neurodegenerative Diseases. In Biometals in Neurodegenerative Diseases pp 415-438.

- Ibrahim IH (2024) Metalloproteins and Metallo proteomics in health and disease. Adv Protein Chem Struct Biol 141: 123-176.

- K Acevedo, S Masaldan, CM Opazo, AI Bush (2019) Redox active metals in neurodegenerative diseases. JBIC Journal of Biological Inorganic Chemistry 24(8): 1141-1157.

- J Liu, S Chakraborty, P Hosseinzadeh, Yu Y, Tian S, et al. (2014) Metalloproteins Containing Cytochrome, Iron-Sulfur, or Copper Redox Centers. Chem Rev 114 (8): 4366-4469.

- Ibrahim IH (2024) Metalloproteins and Metallo proteomics in health and disease. Adv Protein Chem Struct Biol 141: 123-176.

- K Acevedo, S Masaldan, CM Opazo, AI Bush (2019) Redox active metals in neurodegenerative diseases. JBIC Journal of Biological Inorganic Chemistry 24 (8): 1141-1157.

- M Pokusa, A Kráľová Trančíková (2017) The Central Role of Biometals Maintains Oxidative Balance in the Context of Metabolic and Neurodegenerative Disorders. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2017: 8210734.

- A Kumari (2018) Electron Transport Chain. In Sweet Biochemistry. Elsevier pp 13-16.

- P Atkins, G Ratcliffe, M Wormald, J de Paula (2023) Electron transport chains. In Physical Chemistry for the Life Sciences. Oxford University Press.

- M Grossman, I Sagi (2012) Application of Stopped-Flow and Time-Resolved X-Ray Absorption Spectroscopy to the Study of Metalloproteins Molecular Mechanisms. In X-Ray Spectroscopy InTech.

- K Roehm (2001) Electron Carriers: Proteins and Cofactors in Oxidative Phosphorylation. In Encyclopedia of Life Sciences Wiley.

- K Jomova, M Valko (2011) Advances in metal-induced oxidative stress and human disease. Toxicology 283(2-3): 65-87.

- CS Atwood, X Huang, RD Moir, RE Tanzi, AI Bush (2018) Role of Free Radicals and Metal Ions in the Pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s Disease. Met Ions Biol Syst 36: 309-364.

- S Rivera-Mancía, I Pérez-Neri, C Ríos, Tristán-López L, Rivera-Espinosa L, et al. (2010) The transition metals copper and iron in neurodegenerative diseases. Chem Biol Interact 186(2): 184-199.

- M Kawahara, M Kato-Negishi, K Tanaka (2017) Cross talk between neurometals and amyloidogenic proteins at the synapse and the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases. Metallomics 9(6): 619-633.

- AA Belaidi, AI Bush (2016) Iron neurochemistry in Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease: targets for therapeutics. J Neurochem 139 (S1): 179-197.

- K Acevedo, S Masaldan, CM Opazo, AI Bush (2019) Redox active metals in neurodegenerative diseases. JBIC Journal of Biological Inorganic Chemistry 24 (8): 1141-1157.

- MA Akanji, DE Rotimi, TC Elebiyo, OJ Awakan, OS Adeyemi (2021) Redox Homeostasis and Prospects for Therapeutic Targeting in Neurodegenerative Disorders. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2021: 9971885.

- Z Liu, T Zhou, AC Ziegler, P Dimitrion, L Zuo (2017) Oxidative Stress in Neurodegenerative Diseases: From Molecular Mechanisms to Clinical Applications. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2017: 2525967.

- MA Greenough, J Camakaris, AI Bush (2013) Metal dyshomeostasis and oxidative stress in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurochem Int 62 (5): 540-555.

- DL Abeyawardhane, HR Lucas (2019) Iron Redox Chemistry and Implications in the Parkinson’s Disease Brain. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2019: 4609702.

- O Weinreb, S Mandel, MBH Youdim, T Amit (2013) Targeting dysregulation of brain iron homeostasis in Parkinson’s disease by iron chelators. Free Radic Biol Med 62: 52-64.

- E Tokuda, Y Furukawa (2016) Copper Homeostasis as a Therapeutic Target in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis with SOD1 Mutations. Int J Mol Sci 17(5): 636.

- I Sirangelo, C Iannuzzi (2017) the Role of Metal Binding in the Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis-Related Aggregation of Copper-Zinc Superoxide Dismutase. Molecules 22(9): 1429.

- JM Suh, M Kim, J Yoo, Jiyeon Han, Cinthya Paulina, et al. (2023) Intercommunication between metal ions and amyloidogenic peptides or proteins in protein misfolding disorders. Coord Chem Rev 478: 214978.

- M Kawahara, M Kato-Negishi, K Tanaka (2017) Cross talk between neurometals and amyloidogenic proteins at the synapse and the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases. Metallomics 9(6): 619-633.

- EH Choi, MH Kim, SJ Park (2024) Targeting Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Reactive Oxygen Species for Neurodegenerative Disease Treatment. Int J Mol Sci 25(14): 7952.

- J Hroudová, N Singh, Z Fišar (2014) Mitochondrial Dysfunctions in Neurodegenerative Diseases: Relevance to Alzheimer’s Disease. Biomed Res Int 2014: 1-9.

- JR Liddell (2015) Targeting Mitochondrial Metal Dyshomeostasis for the Treatment of Neurodegeneration. Neurodegener Dis Manag 5(4): 345-364.

- MA Akanji, DE Rotimi, TC Elebiyo, OJ Awakan, OS Adeyemi (2021) Redox Homeostasis and Prospects for Therapeutic Targeting in Neurodegenerative Disorders. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2021: 9971885.

- Gogna T, Housden BE, Houldsworth A (2024) Exploring the Role of Reactive Oxygen Species in the Pathogenesis and Pathophysiology of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Disease and the Efficacy of Antioxidant Treatment. Antioxidants 13(9): 1138.

- C Morén, RM deSouza, DM Giraldo, C Uff (2022) Antioxidant Therapeutic Strategies in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Int J Mol Sci 23(16): 9328.

- Pal C (2023) Small-molecules against Oxidative stress mediated neurodegenerative diseases. Chemical Biology Letters 10(4): 626.

- LJ Shinn, S Lagalwar (2021) Treating Neurodegenerative Disease with Antioxidants: Efficacy of the Bioactive Phenol Resveratrol and Mitochondrial-Targeted MitoQ and SkQ. Antioxidants 10(4): 573.

- DS Harischandra, H Jin, A Ghosh, Vellareddy Anantharam, Arthi Kanthasamy, et al. (2016) Antioxidants and Redox-Based Therapeutics in Parkinson’s Disease pp 261-276.

- LR Perez, KJ Franz (2010) Minding metals: Tailoring multifunctional chelating agents for neurodegenerative disease. Dalton Trans 39(9): 2177-2187.

- MA Greenough, J Camakaris, AI Bush (2013) Metal dyshomeostasis and oxidative stress in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurochem Int 62(5): 540-555.

- MG Savelieff, G Nam, J Kang, Lee HJ, Lee M, et al. (2019) Development of Multifunctional Molecules as Potential Therapeutic Candidates for Alzheimer’s Disease, Parkinson’s Disease, and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis in the Last Decade. Chem Rev 119(2): 1221-1322.

- I Sirangelo, C Iannuzzi (2017) The Role of Metal Binding in the Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis-Related Aggregation of Copper-Zinc Superoxide Dismutase. Molecules 22(9): 1429.

- PI Moreira, X Zhu, X Wang, Lee HG, Nunomura A, et al. (2010) Mitochondria: A therapeutic target in neurodegeneration. Biochim Biophys Acta 1802 (1): 212-220.

- IG Onyango, J Dennis, SM Khan (2016) Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Alzheimer’s Disease and the Rationale for Bioenergetics Based Therapies. Aging Dis 7(2): 201-214.

- E Feneberg, M Otto (2020) Genspezifische Therapieansätze bei der Alzheimer-Krankheit und anderen Tauopathien. Nervenarzt 91(4): 312-317.

- GJ McBean, MG López, FK Wallner (2017) Redox‐based therapeutics in neurodegenerative disease. Br J Pharmacol 174(12): 1750-1770.