Mesenteric Phlebosclerosis ~ Clinical Features and Diagnosis

Naoki Mantani1* and Tetsuo Watanabe2

1Internal Medicine, Bayside Clinic, Yokohama, Kanagawa 220-0005, Japan

2Asahi General Hospital, Japan

Submission: September 24, 2024; Published: October 03, 2024

*Corresponding author: Naoki Mantani, Internal Medicine, Bayside Clinic, Yokohama, Kanagawa 220-0005, Japan

How to cite this article: Naoki Mantani* and Tetsuo Watanabe. Mesenteric Phlebosclerosis ~ Clinical Features and Diagnosis. J of Pharmacol & Clin Res. 2024; 10(4): 555791. DOI: 10.19080/JPCR.2024.10.555791

Abstract

Long-term use of gardenia fruit (GF) can cause mesenteric phlebosclerosis (MP). A large cumulative dosage of GF, such as 4000-5000 grams, is necessary for development of MP. Some individual factors may influence susceptibility to MP. Typical MP symptoms are spontaneous pain and tenderness in the right abdomen. CT scans show colonic wall thickening and spotted calcifications in and around the right hemi-colon. During colonoscopy, the bronze coloration and erosion of the colonic membrane is found. Abdominal ultrasound is available for periodical monitoring of MP development. The MP symptoms and the colonic wall thickening are usually reversible after discontinuation of GF.

Keywords: Mesenteric Phlebosclerosis; Gardenia Fruit; Calcification; Ultrasound

Abbreviations: GF: Gardenia Fruit; MP: Mesenteric Phlebosclerosis; THM: Traditional Herbal Medicine; CT: Computed Tomography

What is Mesenteric Phlebosclerosis?

Mesenteric phlebosclerosis (MP) is characterized by the calcification of mesenteric veins that disturbs blood flow from the intestine [1]. Bronze pigmentation appears initially in the right hemi-colon, followed by thickening of the intestine wall. MP presents various symptoms including abdominal pain, diarrhea, and nausea. The wall thickening and calcification of mesenteric veins in MP lesions can be detected through CT scan with high sensitivity [2,3].

Discovery of Mesenteric Phlebosclerosis

MP is slightly different from other adverse effects of traditional herbal medicine (THM). Since the development of modern science, several kinds of adverse events caused by THM have been discovered. Pseudo aldosteronism was first reported in the 1960s [4]. Mesenteric phlebosclerosis was discovered only recently: the first case of MP was reported in 1991 [5], and the disease concept of MP was proposed in 1993 [6]. The well-known outline of MP was established in the 2000s.

MP develops in patients with long-term use of certain Kampo medicines, including Kamishoyosan, Inchinkoto, and Orengedokuto. Most case-reports of MP have been published in Japan and Asian countries. MP patients are rarely observed in Western countries. In the early days of MP discovery, “mesenteric phlebosclerosis” was sometimes called “phlebosclerotic colitis”; however, now it is usually called “mesenteric phlebosclerosis”.

Background of MP

The widespread use of THM has influenced the development of MP. Some people continuously take causal herbs for many years. Estimated reasons for the recent discovery of MP are as follows: 1. MP lesions, which could not be detected in the previous era, have recently been detected by endoscopy and CT scan, 2. Long-term use of causal THM is increasing in Japan and Asian countries. Kampo extract preparations has made it easier to continue taking THM for long periods of time.

Causal Herb Responsible for MP

Causal herb responsible for MP has been unknown until recently. During the past 30 years, there has been increasing evidence that development of MP is associated with long-term use of gardenia fruit (GF) [7]. Pharmacogenetic studies have suggested that geniposide contained in GF is the causative agent of MP. In proximal colon, geniposide is metabolized to genipin by β-glucosidase of colon flora. Genipin can permeate through the enterocyte membrane, and can induce “venous sclerosis” through some mechanisms.

MP and Cumulative Dose of GF

MP occurs among patients with long-term administration of GF. Nagata et al. [8] reported that some cumulative dose of GF is necessary for the development of MP; all MP cases described in the report [8] had been administered more than approximately 5,000 grams of GF in cumulative dosage (e.g., 500g /year×10 years =5000g). Subsequent research (2021) [9] showed that duration of GF intake was relatively longer in symptomatic MP cases than in asymptomatic MP group. Similar to the adverse effects of longterm rhubarb use, some individual differences in drug tolerance also influence the development of MP. In a reported case, MP occurred after administration of 4380g GF (cumulative dose) [10]. Thus, the cumulative dosage “5000g” is never the absolute value. Some patient’s factors may be associated with susceptibility to GF.

Pathological features of MP

MP lesions generally develop in the right side of the colon that is connected to the upper mesenteric vein. The histopathological features are follows [11]; 1. marked fibrous mural thickening with calcification of mesenteric veins and their branches, 2. marked submucosal fibrosis, 3. deposition of collagen around the vessels in the colon mucosa, 4. appearance of foamy macrophages within the wall of small vessels chiefly in the submucosa, 5. lack of vasculitis. Therefore, the name “mesenteric phlebosclerosis” is better than “phlebosclerotic colitis” based on the feature, “lack of vasculitis”.

Clinical features of MP

Typical MP symptoms are spontaneous pain and tenderness in the right abdomen. Diarrhea or constipation is also observed; however, not a few MP patients are asymptomatic. In a few severe cases, MP can cause even perforation and bloody ascites [3]. Nowadays few patients progress to such advanced stage. In case of typical MP, computed tomography (CT) scans show spotted or linear calcifications around the right hemicolon. During colonoscopy, the bronze coloration and multiple erosions of the colonic membrane is found among MP patients. These findings are highly characteristic features. With widespread knowledge of MP, the number of severe MP cases with striking images in CT or colonoscopy has decreased.

Diagnosis

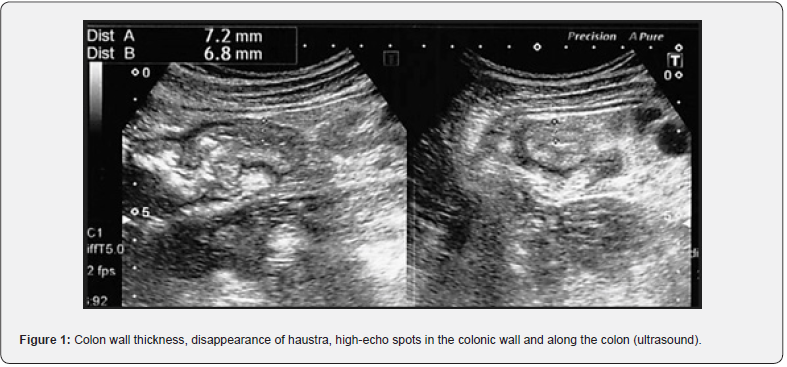

Fecal occult blood test could be positive in MP patients; however, no specific laboratory test has been established. Distinctive image patterns bring us accurate diagnosis. CT scans show colonic wall thickening and spotted or linear calcifications in the colonic mucosa as well as the mesenteric vein and its branches around the right hemi-colon [2]. In typical cases, endoscopy shows bronze-colored mucosa with multiple erosions and ulcerations [12]. Abdominal X-ray is likely to miss the calcification of mesenteric veins. CT scan sensitively detects the MP lesions; however, the relatively expensive cost and the problem of radiation exposure are obstacle to periodical monitoring of MP development. Colonoscopy is also expensive and it takes time and effort. We have reported that abdominal ultrasound is available for periodical monitoring of MP (Figure 1) [13]. Typical ultrasound findings were as follows: (1) wall thickness in submucosal layer at an early stage; (2) disappearance of haustra of the colon; (3) high-echo spots or lines observed in the colonic wall and along the ascending colon. US is non-invasive and therefore suitable for periodical monitoring. In summary, clinical diagnosis of MP is based on the 3 factors; long-term use of GF, the typical symptoms, and the characteristic findings on ultrasound, X-ray, CT scan, and/ or colonoscopy.

Treatment and Prognosis

Many MP cases described in the former reports were severe and underwent immediate surgery. However, the symptoms and the colonic wall thickening of MP lesions are usually reversible [14]. Currently, discontinuation of causative THM and conservative treatment are considered first-line treatment. No recurrence of MP has been reported in patients who recovered after causaldrug discontinuation. Calcification in MP lesions remains for a long time.

Factors associated with the severity of MP

MP cases are generally asymptomatic in early stages. Although MP develops in relation to cumulative dose of GF, there are asymptomatic MP cases even after administration of large cumulative doses such as 15,000 g [8]. Some factors other than cumulative dose may be related to MP severity. For example, individual variation in enterobacterial flora may influence the development of MP. Another report suggested that portal hypertension can be one of the causes of MP [15]. We have previously investigated any factors associated with symptomatic MP [9]. The results suggested that “female” and “small body size” are possibly associated with “symptomatic MP”, and comorbidities that can cause elevated venous pressure, such as liver cirrhosis, COPD, pulmonary infarction, and CRF, are possibly related to severity of MP.

However, such comorbidities were observed among a few cases [9]. Therefore, the real impact of venous pressure cannot be determined at this time. Although venous stasis may play a role in the development of MP, fibrotic thickening of the colonic wall should be the very essence of MP. The pathogenesis of the fibrotic thickening should be clarified in more detail.

Conclusion

As for the development of MP, a large cumulative dosage of GF is necessary condition. In addition, some patient’s factors are associated with susceptibility to MP. We must engage in the early detection of MP by surveillance with ultrasound, CT, and colonoscopy. MP is an adverse event that can be reduced or eradicated with careful observation.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express our special thanks to Dr. Y. Nagata [8] for his support on this manuscript. Until today, the pathology and clinical features of MP has been clarified based on much effort of many researchers involved in gastroenterology and THM. We express our deepest gratitude to all these researchers.

- Short Communication

- Abstract

- What is Mesenteric Phlebosclerosis?

- Diagnosis

- Treatment and Prognosis

- Factors associated with the severity of MP

- Conclusion

- Acknowledgments

- References

References

- Iwashita A, Yao T, Schlemper RJ (2003) Mesenteric phlebosclerosis; a new disease entity causing ischemic colitis. Dis Colon Rectum 46(2): 209-220.

- Yao T, Iwashita A, Hoashi T, Matsui T, Sakurai T, et al. (2000) Phlebosclerotic colitis: Value of radiolography in diagnosis-Report of three cases. Radiology 214(1): 188-192.

- Watanabe T, Nagata Y, Fukuda H, Nagasaka K (2016) Screening for idiopathic mesenteric phlebosclerosis in outpatients undergoing long-term treatment at department of Kampo medicine. Kampo Med 67: 230-243.

- Conn JW, Rovner DR, Cohen EL (1968) Licorice-induced pseudo aldosteronism. JAMA 205: 492-496.

- Koyama Y, Koyama H, Hanajima T, Matsubara N, Shimoda T, et al. (1991) Chronic ischemic colitis causing stenosis, Report of a case. Stomach Intestine 26: 455-460.

- Iwashita A, Takemura S, Yamada Y (1993) Patho morphologic study on ischemic lesions of the small and large intestine. Stomach Intestine 28: 927-941.

- Hiramatsu K, Sakata H, Horita Y (2012) Mesenteric phlebosclerosis associated with long-term oral intake of geniposide, an ingredient of herbal medicine. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 36(6): 575-586.

- Nagata Y, Watanabe T, Nagasaka K (2016) Total dosage of gardenia fruit used by patients with mesenteric phlebosclerosis. BMC complementary and alternative medicine 16: 207.

- Mantani N, Oka H (2021) Systemic analysis for factors associated with symptomatic mesenteric phlebosclerosis in Japanese. Kampo Medicine 72: 58-65.

- Hisanaga E, Sano T, Sata K, Kuribayashi S, Uraoka T (2021) Mesenteric phlebosclerosis associated with the oral intake of Japanese traditional (Kampo) medicines containing gardenia fructus. Clin J Gastroenterol 14: 1453-1458.

- Yao T, Hirahashi M, Kono S, Tsuneyoshi M (2009) Differential diagnosis of idiopathic mesenteric phlebosclerosis and other diseases using pathological characteristics. Stomach and Intestine 44: 153-161.

- Jian D, Weiqiang Z, Lizhang W, Zefeng Z, Jia W (2021) Idiopathic mesenteric phlebosclerosis: clinical and CT imaging characteristics. Quant Imaging in Med Surg 11: 763-771.

- Mantani N, Watanabe T (2020) Ultrasound findings of the colon in four patients of mesenteric phlebosclerosis. J Jpn Soc Coloproctol 73: 361-367.

- Shimizu S, Tomioka H, Ishida E, Yokomizo C, Uejima H (2016) Changes in clinical pictures of mesenteric phlebosclerosis after herbal medicine discontinuation. Stomach and Intestine 51: 483-490.

- Kusanagi M, Matsui O, Kawashima H (2005) Phlebosclerotic colitis: imaging-pathologic correlation. Am J Roentgenol 185:441-447.