Chemical Composition, Antioxidant and Antifungal Activity of Essential Oils of Pogostemon Amaranthoides from (Raya-Bajeta Valleys) Pithoragarh, Uttarakhand Himalayas, India.

Kundan Prasad*

Chemistry Lab, GIC Garkha, Uttarakhand, India

Submission: August 28, 2017;Published: October 23, 2018

*Corresponding author: Kundan Prasad, Chemistry Lab, GIC Garkha, Majhera, Pithoragarh, Uttarakhand, India

How to cite this article: Kundan P. Chemical Composition, Antioxidant and Antifungal Activity of Essential Oils of Pogostemon Amaranthoides from 002 (Raya-Bajeta Valleys) Pithoragarh, Uttarakhand Himalayas, India. J of Pharmacol & Clin Res. 2018; 6(4): 555691. DOI: 10.19080/JPCR.2018.06.555691

Abstract

Pogostemon amaranthoides are wild edible vegetable.

Methods: The plant Pogostemon amaranthoides including leaves, stem, and flowers were extracted by hydro distillation method for 6 hours using Clevenger apparatus. Mineral content in plant was estimated by wet digestion method. Antioxidant activity was done by DPPH assay & ABTS assay.

Results: Total thirty-five compounds were identified constituting 81.26% of the total oil. The main compounds were β-Caryophyllene (15.48), Guaia-3,9-diene (8.27), β-Guaiene (7.15), (E)-, β-Ocimene (7.14), Germacrene B (6.91), β-Himachalene (6.55), β-Vetivenene (4.12) and α-Humulene (3.82). β-Carotene in Pogostemon amaranthoides was found to contain 259.63±1.1.34 mg.100g-1 on a dry weight basis. The free radical scavenging activity (DPPH assay) was 8.14±0.02mM AAE/100g. The inhibition for fungus Sclerotinia sclerotiorum was found to be 17.92-69.58%, Fusarium oxysporium was found to be 22.12- 54.58 % and Curvularia lunata was found to be 40.42-57.50% by the aromatic oil of Pogostemon amaranthoides.

Conclusion: The results data obtained in the present investigation suggest that an essential oil and whole plant possesses strong medicinal activities can be utilized for treatment of diseases and also used as healthy wild editable vegetable.

Keywords: β-Caryophyllene; GC-MS; ASS; Biochemical; phytochemicals and HPLC

Abbreviations: GC: MS gas chromatography/mass spectrometry; GC: FID gas chromatography/flame ionization detector; RI: retention index; HPLC: High performance Liquid chromatography; ABTS: Azinobis (3 benzylthiazole)-6- sulphonic acid; DPPH: Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl; DRDO: Defence Research and Development Organisation; DARL: Defence Agriculture Research Laboratory; GBPNIHESD: Govind Ballabh Pant National Institute of Himalayan Environment & Sustainable Development; IIVR: Indian Institute of Vegetable Research; PDA: Potato Dextrose Agar

Introduction

Pogostemon is a large genus from the family Lamiaceae. Pogostemon amaranthoides Benth leaves are improved blood. The common name of the plants are namnam in local people of Bajeta called it ena. Leaves and stem are the edible part of the plants as wild editable vegetables. The In most cases women suffer from anaemia following childbirth due to iron deficiency their vegetables cure them. Leaves are believed to have medicinal values to cure kidney problem (1). There is no more literature on this plant. Local people of Bajeta and this region its leaves and soft stem are used in increasing cow milk and its health after delivery. This is the first work on this plant. The use of medicinal plants by humans dates back thousands of years due to their medicinal and nutritional properties. Many natural compounds extracted from plants have important biological activities. Among these compounds, we highlight the essential oils, which are increasingly ttracting the attention of various segments of industry due to their multiple functions, especially antioxidant and antimicrobial activities Milene Aparecida Andrade et al. [1]. Essential oils are marketed by various companies as raw material for various products with applications in perfumery, cosmetics, foods, and as adjuncts in medicines, among others. There are approximately 300 essential oils of commercial importance in the world. In the food industry, essential oils, besides imparting aroma and flavour to food, have important antioxidant activity, a property that further encourages its use Bizzo et al. [2].

Those important oils include a diffusion of risky molecules along with terpenes, terpenoids and phenol derived fragrant and aliphatic compounds, which might have bactericidal, antiviral, and fungicidal consequences. Terpenoids are the primary elements of the important oils answerable for the aroma and flavour Nuzhat & Vidyasagar [3]. Medicinal and aromatics vegetation play a huge role within the financial system of Morocco. As a part of a contribution to the improvement of herbal Moroccan background, many kinds of research are presently testing the efficacy of medicinal plant extracts against human’s sicknesses or plant diseases or for business cause Fadel et al. [4]. Fusarium species are crucial plant pathogens causing diverse ailments which encompass crown rot, head blight, and scab on cereal grains (Nelson et al 1994), and they’ll once in a while purpose infection in animals. Curvularia lunata is a famous fungal plant pathogen which can motive disorder in people and different animals. Sclerotinia sclerotiorum is a plant pathogenic fungus and can cause a disease called white mould if conditions are conducive. S. sclerotiorum can also be known as cottony rot, watery soft rot, stem rot, drop, crown rot and blossom blight. The present paper deals with the estimation of antioxidants, aromatic oil, antioxidant and antifungal activity and nutraceuticals of whole plants parts of medicinally and nutritionally important plants Pogostemon amaranthoides. The plants can use in pharmaceutical and nutrients raw material in the formulation of many drugs and foods.

Material and Methods

Plant Material

Arial parts of Pogostemon amaranthoides was collected in the month of September 2006 to 2018 from Homtala (Bajeta, Munsyari), Pithoragarh, India in the Kumaon Himalayas. The plant was first identified in the Department of Botany, Kumaun University, Nainital. The collected plant material was first washed with cold water to remove the soil particles and then shade dried. The dried material was finely powdered in the grinding machine and weighed in an electrical balance.

Chemicals

Standard of xanthophyll, α-carotene, β-carotene and DL- α-tocopherol was procured from Sigma Chemical Co. St Louis, USA. Individual standard was accurately weighed, developed and diluted with HPLC grade ethanol. Petroleum ether, methanol, ethyl acetate and anhydrous sodium sulphate and other chemicals and reagents used in this study was purchased Merck Chemical Co. Mumbai, India. 1,1-Diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radical, gallic acid, ascorbic acid, chlorogenic acid, caffeic acid, ρ-coumaric acid, 3-hydroxybenzoic acid, catechin and quercetin was procured from Sigma-Aldrich (Steinheim, Germany). Sodium carbonate, 2-(n-morpholino) ethanesulfonic acid (MES buffer), potassium persulphate, ferric chloride, sodium acetate, potassium acetate, aluminium chloride, glacial acetic acid and hydrochloric acid from Qualigens (Mumbai, India), and 2,2_-azinobis(3- ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulphonic acid) (ABTS), 2,4,6-tri-2- pyridyl-1,3,5-triazin (TPTZ), methanol and ethanol from Merck Company (Darmstadt, Germany).

Isolation of Essential Oil

The plant Pogostemon amaranthoides including leaves, stem, and flowers extracted by hydro-distillation method for 5 hours using Clevenger apparatus. The oil was dried over anhydrous sodium sulphate and stored at room temperature in a sealed vial until analysis was performed. The percentage oil yield was calculated based on the dry weight of the plant. The oil yield was (0.15%).

GC and GC/MS Analyses and Identification

Essential oil analyses were performed by GC-MS and GC-FID on a Shimadzu QP-2010 instrument, equipped with FID, in the same conditions. The percentage composition of the oil sample was computed from the GC peak areas without using correction for response factors. The oil was analyzed using a Shimadzu GC/ MS Model QP 2010 Plus, equipped with Rtx-5MS (30m×0.25mm; 0.25mm film thickness) fused silica capillary column. Helium (99.999%) was used as a carrier gas adjusted to 1.21ml/min at 69.0 K Pa, splitless injection of 1mL, of a hexane solution injector and interface temperature was 270 0C, oven temperature programmed was 50-2800 C at 30 C/min. Mass spectra was recorded at 70 eV. Ion source temperature was 2300 C. The identification of the chemical constituents was assigned on the basis of comparison of their retention indices and mass spectra with those given in the literature (Kundan and Deepak, 2018). Retention indices (RI) were determined with reference to a homologous series of normal alkanes, by using the following formula Kovats [5].

t1 R – the net retention time (tR – t0)

t0 – the retention time of solvent (dead time)

tR – the retention time of the compound.

CN – number of carbons in longer chain of alkane

Cn– number of carbons in shorter chain of alkane

n - is the number of carbon atoms in the smaller alkane

N - is the number of carbon atoms in the larger alkane

Total Phenolic

The whole plant was dried in shade and powdered using electrical grinder. The amount of total phenolic content was estimated following Singleton et al. [6] with modification. The reaction mixture contained 100 Dl of sample extract, 500 Dl Folins-Ciocalteu’s reagent (freshly prepared), 2 ml of 20% Sodium Carbonate and 5ml of distilled water. After 15min reaction at 450C the absorbance at 650nm was measured using spectrophotometer. The result was expressed as mg of Catechol equivalent per 100g of dry weight.

Biochemical Analysis

The moisture content was estimated by dried in electrical oven at 800 C for 24 hours and expressed on a percentage basis. The dried leafs was powdered separately in electric mill to 60 mesh size. The fine leaves powders so obtained was used for further biochemical and mineral analysis (three replication of each parameter). The chlorophyll content in dry leaves powder was estimated by method Singleton [6]. Tannins content was estimated as described by method Schanderl [7]. Total carbohydrate content in plant leaves was estimated by the Dubois et al. [8], Starch by Hodge and Hofreiter [9]. Total nitrogen was estimated by Micro- Kjeldahl method, according to AOAC method, 1985. Crude protein was calculated as Kjeldahl N x 6.25 (based on assumption that nitrogen constitutes 16.0% of a protein). The content of crude fat was estimated by AOAC method, 1970. Amylose content in plant leave was estimated, as described method MeCready et al. [10] Julians [11]. Cellulose content was estimated as described by method Updegraff [12]. Crude fiber content was estimated as described by methods (Maynard, 1978).

Mineral Analysis

Ash content was estimated by AOAC method, 1985 and ash insoluble content was estimated by method Peach et al. [13] and Mishra R [14]. Mineral content in plant was estimated by wet digestion method. 1.0 g plant material was first digested with conc. HNO3 (5ml each), followed by application of 15ml of triacid mixture (HNO3, HClO4 and H2SO4, 10:4:1, v/v) heated at 2000 C and reduce to 1ml. The residue after digestion was dissolved in double distilled water, filtered and diluted to 100ml. This solution was used for the estimation of minerals. Macro minerals viz., Na, K, Ca and Li was estimated by AIMIL, Flame Photometer while micro elements viz. Fe, Cu, Mn, Zn and Co was estimated by Atomic Absorption Spectrophotometer, model 4129, Electronic Corporation of India Ltd. Phosphorous and sulpher content was estimated by method Allen [15].

Ascorbic Acid

Ascorbic acid content was estimated by method Witham et al. [16] with modification. Dry leaves powder (2.0 g) was extracted with 4% oxalic acid and made up to 100 ml and centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for a 10 minute. 5 ml supernatant liquid was transferred in a conical flask, followed by addition of 10ml 4% oxalic acid and titrated against standard dye solution (2, 6-dichlorophenol indophenol) to a pink end point. The procedure was repeated with a blank solution omitting the sample.

Extraction and Isolation of Carotenoids and Tocopherol

Dried plant material (1.0 g of each) was extracted with light petroleum ether/methanol/ethyl acetate (1:1:1, V/V/V, 4 x 30ml) until the extracts became colorless. The extract was mixed in a 250ml separating funnel, shaken vigorously and allowed to stand for phase separation. Upper layer was collected in a 100ml flask (Borosil India Co. Ltd.) and lower layer was shaken with 50ml water and 50ml petroleum ether for phase separation. Upper layer was mixed with the first extract. The organic extract was dried over anhydrous sodium sulphate (10g), filtered and evaporated to dryness in a Rotary Vacuum Evaporator under reduced pressure. The residue was dissolved in light petroleum ether (5ml) and filtered by 0.2μm membrane filter prior to HPLC analysis.

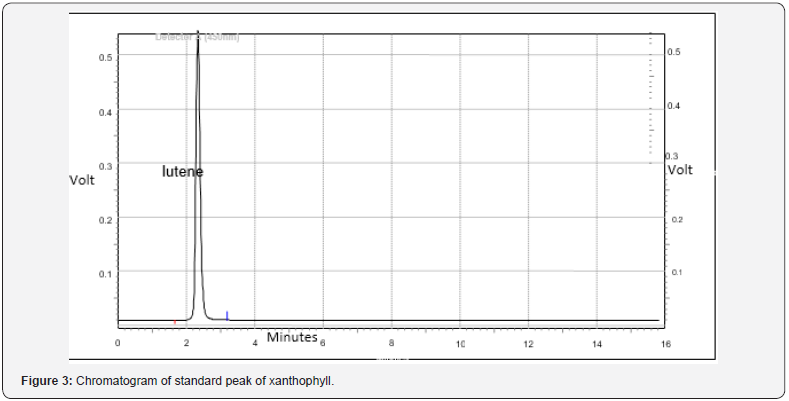

HPLC Analysis

All the samples was analyzed using Shimadzu HPLC interfaced with model SPD-10 AVP Variable wavelength (190-750nm) UVVis detector, Column used was C18 Phenomenex® (150x4.60nm), pore size 5μm with solvent system 8:2:40:50 (methanol, ethyl acetate, acetonitrile and acetone), flow rate 0.7ml/min, run time 20minutes and detector wavelength was 450nm. The HPLC condition for the estimation DL-α-tocopherol was adopted as described in Kurilich et al. [17] and Kundan & Deepak, 2018.

Extract Preparation for Antioxidant Analysis

Take 1.0 ml E. Oil of plants and mixed with in 4.0ml DMSO (Dimethyl sulfoxide). The prepared extract was used for the determination of antioxidant activity i.e., DPPH assay & ABTS assay in samples.

Diphenyl-1-Picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) Assay

Free radical DPPH scavenging assay Brand-Williams et al. [18] was slightly modified for the present study. DPPH (100μM) was prepared in 80% (w/v) ethanol and 2.7ml mixed with 0.9ml of sample extract and allowed to stand in the dark (22±10C, 20min). The reduction in the absorbance at 520nm was recorded and results expressed in mM ascorbic acid equivalent per 100g (mMAAE /100g).

Azinobis (3 Benzylthiazole)-6- Sulphonic Acid (ABTS) Assay

Total antioxidant activity was measured by improved ABTS (ethylbenzothiazoline 6- sulphonic acid) radical scavenging method Cai et al. [19]; Bhatt et. al. 2016). In brief, ABTS (7.0μM) and potassium persulphate (2.45 μM) was added in amber colored bottle for the production of ABTS cation (ABTS˙+) and kept in the dark (16 h, 22±1°C). ABTS˙+ solution was diluted with 80% (v/v) ethanol till an absorbance of 0.700±0.05 at 734nm is obtained. For sample analysis, 3.90ml of diluted ABTS˙+ solution was added to 0.10 ml of methanolic extract and mixed thoroughly. The reaction mixture was allowed to stand (22±1oC, 6min, dark) and the absorbance was recorded at 734nm with respect to blank. A standard curve of various concentrations of ascorbic acid is prepared in 80% v/v methanol for the equivalent quantification of antioxidant potential with respect to ascorbic acid. A result was expressed in mM ascorbic acid equivalent per 100g (mM AAE /100g).

Plant Pathogenic Fungi

The foliage born and soil born fungi were obtained from the Department of Plant Pathology, College of Agriculture, G. B. Pant University of Agriculture & Technology, Pantnagar, India. The pure culture of these pathogenic fungal species were maintained on Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA) and stored at temperature below 40 C for further activity.

Antifungal Activity

Screening essential oil for antimicrobial activity was done by the well diffusion method which is normally used as preliminary check for antimicrobial efficiency of essential oil.

Results

Method of Media Preparation

At first 200gm pealed potato was cut into fine pieces then it was boiled in 500ml of distilled water for 30 minutes and filtered through muslin cloth. 20gm of Agar-Agar was dissolved in 500ml boiling water then potato extract was added in boiling mixture and mixed thoroughly by stirring with glass rod. 20gm of dextrose was added to the medium and transferred to about 200ml in each 500ml capacity flasks and were plugged with non-absorbent cotton plugs. The pH of the medium was adjusted to 7.0±0.2 and then allows the medium to sterilize at 15 lbs p.s.i (121.6°C) for 15minutes.

Growth and Colony Characters

20 ml sterilized medium was poured into sterilized Petriplates. 5mm disc of fungal growth of each fungal was cut with the help of cork borer from 10 days old culture growth on PDA. These discs were placed onto sterilized PDA plate in a manner so that the growth of the fungus touches the PDA in the plate and incubated for 7 days at 25±2°C. After incubation for 7 days, radial growth was measured.

Bioassay of Essential Oils Against Different Pathogen

Poisoned Food Technique: Prepared Potato Dextrose Agar medium and then add required amount of essential oil as to get a final desired concentration and thoroughly mixed. Culture of test fungus was multiplied growing on PDA medium for 7 days at 25±2°C. Small disc of fungus culture was cut with sterile cork borer and transferred aseptically in the centre of the Petri-dish containing the medium having desired essential oil concentration. Suitable checks, with the culture discs on PDA without essential oil were maintained. Plates were incubated at 25±2°C and the fungal colony diameter is measured at every 24h. The colony diameter measured at each concentration of essential oil is compared with check to evaluate the toxicity of essential oil towards the test fungus. For essential oil, the different concentration of respective essential oil was prepared by dissolving weighed quantity of essential oil in a measured volume of sterilized distilled water. The amount of solution to be added to PDA medium was calculated by following formula:

C1V1 = C2V2

Where,

C1 = Concentrations of stock solution (μg/ml)

C2 = Desired concentration (μg/ml)

V1 = Volume (ml) of the stock solution to be added

V2 = Measured volume (ml) of the PDA medium

The measured amount of each essential oil was added to make a concentration of 25ppm, 50ppm, 100ppm, 250 ppm and 500ppm, separately and mixed thoroughly before plating. 20ml toxicated medium with different treatment were poured in each Pertiplate. After that, one 5 mm mycelial disc of 10days old culture of each fungal isolate was inoculated separately and incubated at 25 ± 2° C for 7 days. The radial growth was measured in mm. by scale. Per cent inhibition were calculated by using following formula Given by Mckinney [20]:

Percent inhibition = X-Y/X *100

Where,

X = Radial growth in check

Y = Radial growth in treatment

Results and Discussion

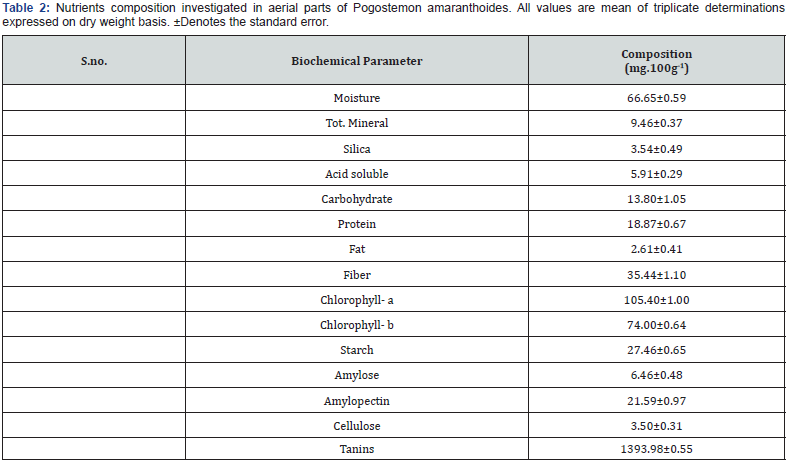

The GC and GC-MS analyses of essential oil of Pogostemon amaranthoides resulted in the identification of thirty-five compounds (Table 1). The oil yield was (0.20%) by raw material weight. Both, the major as well as minor constituents were identified by their retention indices and comparison of their mass spectra. Total fifty-seven compounds were identified constituting 81.26% of the total oil. The main compounds were β-Caryophyllene (15.48), Guaia-3,9-diene (8.27), β-Guaiene (7.15), (E)-, β-Ocimene (7.14), Germacrene B (6.91), β-Himachalene (6.55), β-Vetivenene (4.12) and α-Humulene (3.82). The main minor compounds were 3-Octanone (0.05), β-Myrcene (0.06), Phenylacetaldehyde (0.10), (+)-Camphor (0.10), Italicene (0.10), Camphene (0.11), α-Pinene (0.14) and Cryptomeridiol (0.14). The presence of β-Caryophyllene (15.48) show good source of natural β-Caryophyllene (Figure 1). The amounts of certain nutrients in Pogostemon amaranthoides are presented in (Table 2). Fat, protein and total carbohydrate content in Pogostemon amaranthoides was found to be 2.61±0.41, 18.87±0.67 and 13.80±1.05 g.100g-1 respectively on dry weight basis respectively (Figure 2). Starch, Amylose and Amylopectin content in Pogostemon amaranthoides was found to be 27.46±0.65, 6.46±0.48 and 21.59±0.97 g.100g-1 respectively. The energy content of plants was determined by multiplying the crude protein, crude lipid and total carbohydrate content by the factor 4, 9 and 4 respectively Osborne & Voogt [21]. The calorific values of the plant leaves were found 154.17 K.Cal.100g1.

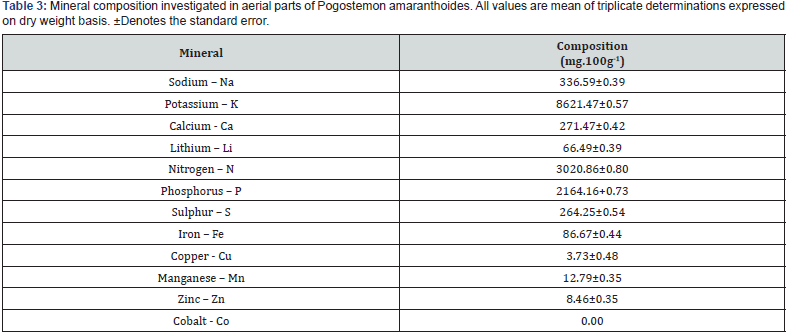

The cellulose, crude fiber and moisture content were found 3.50±0.31, 35.44±1.10 and 66.65±0.59g.100g-1 respectively. The mineral content was found 9.46±0.37 g.100g-1 on dry weight basis. Silica was found 3.54±0.49 g.100g-1 and acid soluble ash was found 5.91±0.29 g.100g-1. The content of chlorophyll-a and chlorophyll-b in aerial parts of plants were found 105.40±1.00 and 74.00±0.64 mg.100g-1 on dry weight basis. The mineral content of Pogostemon amaranthoides is presented in Table 3. The contents of Sodium, Potassium, Calcium and Lithium Pogostemon amaranthoides was found 336.59±0.39, 8621.47±0.57, 271.47±0.42 and 66.49±0.39 mg.100g-1 respectively on dry weight basis (Figure 3). The contents of Nitrogen, Phosphorus and Sulphur Pogostemon amaranthoides was found 3020.86±0.80, 2164.16+0.73 and 264.25±0.54 mg.100g-1 respectively on dry weight basis. The micronutrients contents of Iron, Copper, Manganese, Zinc and Cobalt in aerial parts of plants were found 86.67±0.44, 3.73±0.48, 12.79±0.35, 8.46±0.35 and 0.00 respectively on dry weight basis.

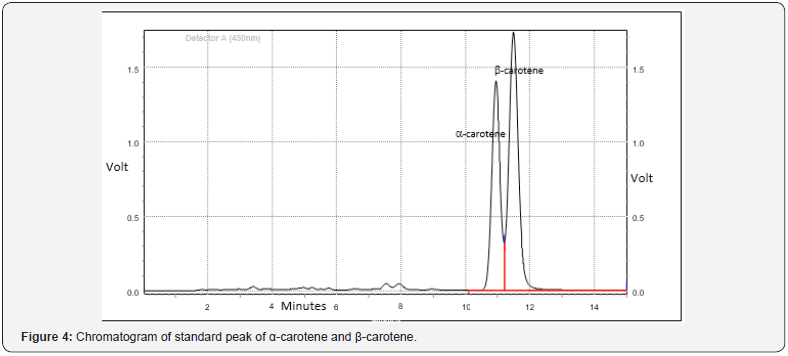

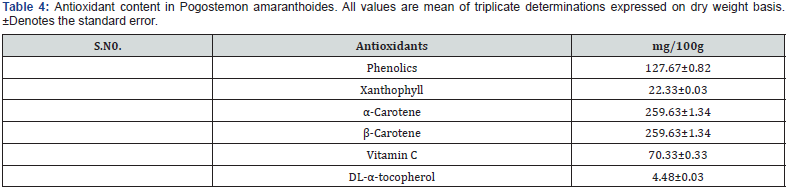

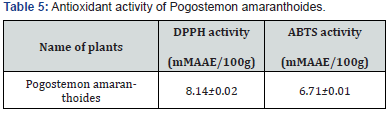

Antioxidant content in Pogostemon amaranthoides is presented in Table 4. Total phenolics in Pogostemon amaranthoides was found to contain 127.67±0.82 mg.100g-1 on a dry weight basis. Xanthophyll in Pogostemon amaranthoides was found to contain 22.33±0.03 mg.100g-1 on a dry weight basis. α-Carotene in Pogostemon amaranthoides was found to contain 259.63±1.34 mg.100g-1 on a dry weight basis. β-Carotene in Pogostemon amaranthoides was found to contain 259.63±1.34 mg.100g-1 on a dry weight basis (Figure 4). The content of Vitamin C in Pogostemon amaranthoides was found to be 70.33±0.33mg.100g-1. DL-α-tocopherol in Pogostemon amaranthoides was found to contain 4.48±0.03mg.100g-1 on the dry weight basis. The essential oil showed good DPPH and ABTS radical scavenging activity (Figure 5). Antioxidant activity of plants Pogostemon amaranthoides analyzed (Table 5). The free radical scavenging activity (DPPH assay) was 8.14±0.02mM AAE/100g recorded in Pogostemon amaranthoides aromatic oil. Total antioxidant activity (ABTS assay) was found (6.71±0.01 mM AAE/100g) in Pogostemon amaranthoides aromatic oil. This activity is significant, especially since this essential oil are composed mainly of monoterpenes and sesquiterpenes hydrocarbons and oxygenated ones which have a moderate activity compared to phenolics and vitamin C. This result might be related to the antioxidant activity of our essential oil.

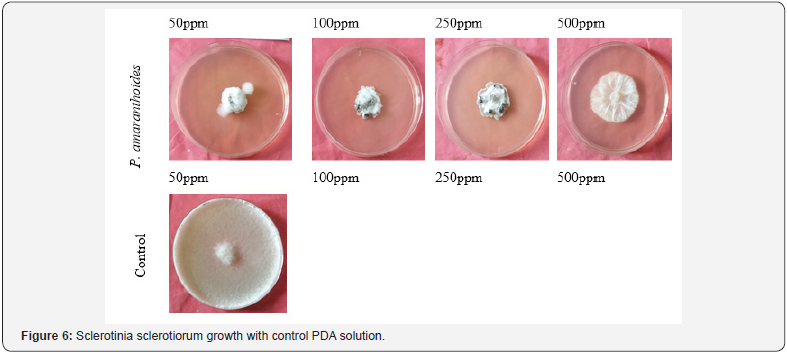

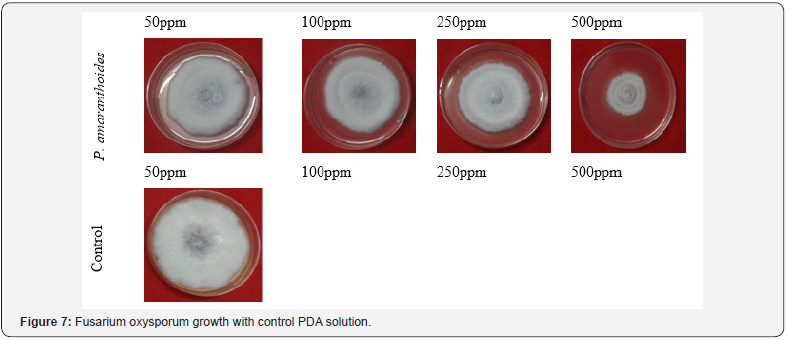

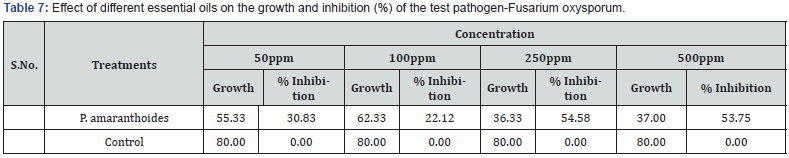

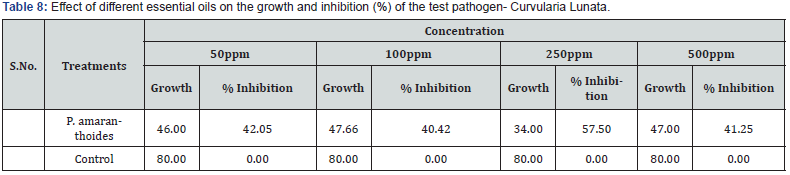

All the concentration of plant aromatic oils had shown activity against test fungal organisms. Effect of different essential oils on the growth and inhibition (%) of the test pathogen- Sclerotinia sclerotiorum are shown in Table 6. The growths of fungus Sclerotinia sclerotiorum are presented in Figure 6 against Pogostemon amaranthoides essential oil. The results showed that increase in concentration of aromatic oils increased zone of inhibition. The inhibition for fungus Sclerotinia sclerotiorum was found to be 17.92- 69.58 % by the aromatic oil of Pogostemon amaranthoides. All the concentration of plant aromatic oils had shown activity against test fungal organisms. Effect of different essential oils on the growth and inhibition (%) of the test pathogen- Fusarium oxysporum are shown in Table 7. The growths of fungus Fusarium oxysporum are presented in Figure 7 against Pogostemon amaranthoides essential oil. The inhibition for fungus Fusarium oxysporium was found to be 22.12- 54.58 % by the aromatic oil of Pogostemon amaranthoides. All the concentration of plant aromatic oils had shown activity against test fungal organisms. The growths of fungus Curvularia Lunata are presented in Figure 8 against Pogostemon amaranthoides essential oil. The inhibition for fungus Fusarium oxysporium was found to be 40.42-57.50% by the aromatic oil of Pogostemon amaranthoides. The results of growth and % of inhibition presented in Table 8. All the essential oils had low amounts of phenolic compounds but showed good antioxidant activity. The diversified mono- and sesquiterpenoids present in the complex mixture of essential oils might be responsible for the good antioxidant activity because of synergetic effects of the constituents. This can be evidenced by a report which says that antioxidant capacity is affected by other bioactive compounds and could involve synergistic effects Sanchez et al. [22].

Conclusion

The essential oil and antioxidant phytochemical from Pogostemon amaranthoides showed a qualitative and quantitative makeup of constituents [23,24]. The plants oils are show good antifungal activity. Clinically, this herb can be a good source of herbal medicine for the treatment of diseases indigenously. The study will also help to generate a database of species which can be exploited scientifically and judiciously in the future by local people and so that ecological balance is maintained [25,26]. The results obtained in the present study suggest that the essential oil of Pogostemon amaranthoides possesses medicinally active compounds. This is the first report on the plants Pogostemon amaranthoides at high altitudes of Kumaon Himalayas. Raya Bajeta Valley is store of medicinal plants so there is great need to investigation on these medicinal plants [27,28].

Acknowledgement

The authors are thankful to Dr H K Pandey and Dr Rawat, Scientist D and Head, Herbal Medicine Division, DRDO (DARL), Pithoragarh for providing laboratory facilities to work on this aspect. We are grateful to Professor Y.P.S. Pangti, Department of Botany, Kumaun University, Nainital for the identification of Plant. The authors are grateful to AIRF, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi for the Gas Chromatography coupled with Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS). The authors are grateful to Professor Ganga Bisht, Head of Department of Chemistry, K U, Nainital for providing the necessary facilities and Dr. I. D. Bhatt Scientist-D, GBPNIHESD, Kosi-Katarmal, Almora for provide antioxidant activity. Authors are also grateful to Dr. Jagdeesh Singh, Principal Scientist, IIVR- Varanasi for HPLC analysis to work on this aspect. Thanks are due to the department of Plant pathology bio control lab, G B Pant University of Agriculture and Technology Pantnagar for antifungal activity determination.

References

- Andrade MA, das Graças Cardoso M, de Andrade J, Silva LF, Teixeira ML, et al. (2013) Chemical Composition and Antioxidant Activity of Essential Oils from Cinnamodendron dinisii Schwacke and Siparuna guianensis Aublet. Antioxidants 2(4): 384-397.

- Bizzo H, Hovell AMC, Rezende CM (2009) Oleos essenciais no Brasil: Aspectos gerais, desenvolvimento e perspectivas. Quím Nova 32(3): 588-594.

- Nuzhat T, Vidyasagar GM (2013) Antifungal investigations on plant essential oils. International Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences 5: 19-28.

- F Fadel, B Chebli, S Tahrouch, A Benddou, A Hatimi (2011) Activité Antifongique D’extraits De Ceratonia Siliqua Sur La Croissance In Vitro De Penicillium Digitatum (*) Bull Soc Pharm Bordeaux 150(1-4): 19- 30.

- Kovats E (1958) Characterization of organic compounds by gas chromatography. Part 1. Retention. indices of aliphatic halides, alcohols, aldehydes and ketones. Helv Chim Acta 41: 1915-1932.

- Singleton VL, Orthofer R, Lamuela Raventos RM (1999) nAnalysis of total phenols and other oxidation substrates and antioxidant by means of Folin-Ciocalteau reagent methods. Enzymol 299: 152-178.

- Schanderl SH (1970) In: Method in Food Analysis Academic Press, New York, USA, pp. 709.

- Dubois M, Gilles KA, Hamilton JK, Rebers PA, Smith F (1956) Anal Chem 26: 350.

- Hodge JE, Hofreiter BT (1962) In: Method in Carbohydrate Chemistry (Eds. Whistler RL and Be Miller, JN, Academic Press, New York, USA.

- MeCready RM, Guggolz J, Siliviera V, Owines HS (1950) Anal Chem 22: 1156.

- Julians BO (1971) Simplified Assay for Milled-Rice Amylose. Cereal Sci Today 16: 334-338.

- Updegraff DM (1969) Semimicro determination of cellulose in biological materials. Anal Biochem 32(3): 420-424.

- Peach K, Tracy MB (1956) Modern method of plant analysis, Springer- Verlag, Heidelberg, Germany.

- Mishra R (1968) Ecological work book. Oxford and IBH Pub Co., New Delhi, India.

- Allen SE (Eds.) (1977) Chemical analysis of ecological materials. Blackwell Scientific Publication Oxford, USA.

- Witham FH, Blaydes DF, Devlin RM (1971) Experiments in plant physiology, Van Nostrand, New York, USA, pp. 245.

- Kurilich AC, Tsau GJ, Brown A, Howard L, Klein BP (1999) Carotene, tocopherol and /ascorbate content in subspecies of Brassica oleracea. J of Agril and food chem 47(4): 1576-1581.

- Brand Williams W, Cuvelier ME, Berset C (1995) Use of a free radical method to evaluate antioxidant activity. LWT-Food Science and Technology 28(1): 25-30.

- Cai Y, Luo Q, Sun M, Corke H (2004) Antioxidant activity and phenolic compounds of 112 traditional Chinese medicinal plants associated with anticancer. Life Sciences 74(17): 2157-2184.

- McKinney HH (1923) Influence of soil temperature and moisture on infection of wheat seedlings by Helminthosporium sativum. J Agri Res 26: 195-217.

- Osborne DD, Voogt P (1978) Calculation of Calorific Value. In the Analysis of Nutrients in Foods. Academic Press, New York, USA, pp. 239-240.

- Sanchez MC, Larrauri JA, Saura CF (1999) Free radical scavenging capacity and inhibition of lipid oxidation of wines, grape juices and related polyphenolic constituents. Food Res Int 32(6): 407-412.

- AOAC (1970) Official Method of analysis (11th Edn.) Association of official analytical chemists, Washington DC, USA.

- AOAC (1985) Official method of analysis (10th Edn.) Association of official agriculture chemicals, Washington DC, USA.

- Bhatt ID, Dauthal P, Rawat S, Gaira KS, Jugran A, et al. (2012) Characterization of essential oil composition, phenolic content, and antioxidant properties in wild and planted individuals of Valeriana jatamansi Jones. Scientia Horticulturae 136: 61-68.

- Maynard AJ (1970) Method in food analysis. Academic press New York, USA, pp 176.

- Chhoeda, Ugyen Yangchen (2017) Wild Vegetable Diversity and their Contribution to Household Income at Pat-shaling Gewog, Tsirang. Bhutan Journal of Natural Resources & Development. BJNRD 4(1): 30- 38.

- Kundan P, Deepak C (2017) Antioxidant Activity, Phytochemical and Nutrients of Didymocarpus pedicellata r.br from Pithoragarh, Uttarakhand Himalayas, India. J of Pharmacol & Clin Res 4(3): 555640.