Abstract

Leatherback Sea Turtles or Leatherbacks (Dermochelys coriacea Vandelli 1761), the largest living turtle species on Earth, are classified as Vulnerable (VU) by IUCN. They can be found regularly in the Mediterranean, although they are rare and are not known to nest in the area. The present study aims to provide an overview of the bycatch and stranding of Leatherback Sea Turtles in the Gaza Strip, Palestine. The study, which extended from 2005 to 2024, relied on repeated field visits to the Gaza Strip coast (42 km) and its facilities, holding meetings and discussions with relevant parties, and following up on what is published by local media and social media regarding sea turtles, in addition to taking some measurements, information and documentary photos. Despite their rarity, most of the individuals encountered during the study, whether alive or dead, were adults or sub-adults, having carapaces of more than 90 cm long. Every year, one or two Leatherbacks are incidentally caught or stranded on the shores of the Gaza Strip. Interviews with several stakeholders revealed that Leatherbacks stranded on beaches died from diseases or injuries resulting from bycatch, collisions with fishing vessels, ingestion of floating plastic bags or debris, or entanglement in damaged or abandoned fishing gear at sea. The story of the slaughter and eating of a large Leatherback that had incidentally fallen into a fishing net because one of its front flippers had been hit by an iron hook, by the Gazans, who were suffering from the Israeli siege, on April 4, 2008, was a painful scene broadcast on television screens and websites, even though the slaughter and eating of sea turtles is common in many countries around the world. But unfortunately, this story has been politically exploited by malicious Israeli parties or those sympathetic to the Israeli occupation of Palestine. Local threats to Leatherbacks and other sea turtle species in the Gaza Strip include fisheries bycatch, ship strikes, marine pollution and debris that can cause Leatherbacks and other sea turtle species to accidentally swallow plastic objects or bags, mistaking them for jellyfish, and climate change. Finally, the study recommended the need to protect Leatherbacks and all sea turtle species as creatures that deserve life in addition to being globally threatened.

Keywords: Leatherbacks; Sea turtles; Mediterranean Sea; Fisheries bycatch; Stranding; Marine debris; Gaza Strip; Palestine

Introduction

Leatherback Sea Turtles or simply Leatherbacks (Dermochelys coriacea Vandelli 1761) are the largest living turtle species on Earth. However, there are no confirmed records of nesting by leatherbacks in Mediterranean so individuals observed in this region are assumed to originate from Atlantic Ocean colonies [1]. Among sea turtle species, Leatherbacks are known to grow to large sizes quickly and may reach sexual maturity faster than hard-shelled sea turtles [2]. According to Zug and Parham [3], the carapace length is usually 130-170 cm and the mass of the turtle is usually less than 500 kg. Leatherbacks are dark in color with white and pink spots, and females can be distinguished from males by their larger size and a distinctive pink spot on top of their heads. Leatherbacks are easily identified by the narrow ridges that run along their carapace. It is worth mentioning that these turtles differ from other sea turtle species in that they have a soft, flexible skin shell instead of the hard, bony shell that other sea turtles have. This unique feature is actually why they are called Leatherbacks [4]. Having a softer shell allows Leatherbacks to dive deeper reaching more than 1,000 meters and withstands pressure changes better than turtles with harder shells [5,6]. Adult Leatherbacks feed primarily on jellyfish (Phylum Cnidaria or Coelenterata), making them a natural enemy, as they can eat hundreds of jellyfish per day [7-10]. Unlike many other sea turtles that prefer warm waters, the Leatherback Sea Turtle has insulated layers of fat and a unique circulatory system that allows it to function well even in extremely cold ocean waters.

Leatherback turtles are classified Vulnerable (VU) by the International Union for Conservation of Nature – IUCN although it was classified as critically endangered as pointed out by James et al. [11]. Threats to Leatherbacks and other sea turtle species include incidental capture in fisheries, exploitation for meat and egg, vessel strikes, ocean pollution and marine debris, loss of nesting habitat, predation on nests and hatchlings, introduction of exotic predators, human disturbance including coastal lighting and habitat development, and climate change [12-18]. Of course, efforts to restore their numbers require international cooperation because turtles roam vast areas of the world’s oceans, and beaches vital to their nesting are found in many countries. A large number of scientific studies have addressed the status of Leatherbacks and their biological and ecological aspects worldwide, and many important studies in the countries surrounding the Mediterranean have contributed to enriching this topic [19-31]. Scientific studies on Leatherback Sea Turtles in the occupied Palestinian territories appeared to be very scarce. Some Palestinian studies [32-34] have indicated the presence of three species of sea turtles in the Mediterranean waters of the Gaza Strip; namely, the Loggerhead Sea Turtle (Caretta caretta), the Green Sea Turtle (Chelonia mydas), and the Leatherback Sea Turtle (Dermochelys coriacea); where the Leatherback Sea Turtle is considered the least abundant species. Strandings and bycatch of several sea turtle species, including the one in question, have been recorded along the 42-km coast of the Gaza Strip, as noted and confirmed by Abd Rabou [32] and Abd Rabou et al [35]. Therefore, the present study aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the bycatch and stranding of Leatherback Sea Turtles (Dermochelys coriacea Vandelli 1761) in the Gaza Strip, Palestine. The importance of this work stems from the fact that it is the first study that addresses some descriptive details about this species of sea turtle in the occupied Palestinian territories.

The study area: The Gaza Strip

The Gaza Strip (31˚25'N, 34˚20'E) is an arid to semi-arid strip of the occupied Palestinian territories along the southeastern Mediterranean Sea (Figure 1), covering an area of about 365 km2. The current population exceeds 2.3 million, the majority of whom are refugees registered with the United Nations, making the Gaza Strip one of the most densely populated places in the world [36]. The length of the Palestinian coast in the Gaza Strip on the Mediterranean Sea is about 42 km. The Gaza Strip beach is full of facilities, chalets, rest houses, cafeterias and other types of human uses of the coast, most of which are lit, which discourages the possibility of sea turtles nesting and hatching. In the summer, the coastal environment of the Mediterranean Sea in the Gaza Strip is crowded with swimmers and vacationers who find in the marine environment and its yellow beach the only outlet for them in light of the repeated Israeli wars and attacks on the besieged Gaza Strip from all directions. There are no less than 3,500 fishermen in the Gaza Strip working on more than 1,000 fishing boats of different sizes, shapes and capacities, and the total fish production is 3,500-4,000 tons annually [37]. The Directorate General of Fisheries at the Ministry of Agriculture is the competent, responsible and authorized body to ensure maximum utilization of fish resources in the Palestinian territories.

Methodologies

The current study relies on a descriptive and cumulative approach to obtaining information, extending over a period of 20 years starting from 2005 to 2024. During this long period of time, repeated field visits and ecological trips were made by the author and his university students studying vertebrate and invertebrate zoology, ecology, biodiversity, marine biology and oceanography, to hotspots along the 42-km coast of the Gaza Strip. Special visits were also made to the fishing ports in the Gaza Strip and the fish markets (Dalalah Market or Al-Hisba) in an attempt to investigate various marine organisms including sea turtles. Meetings and discussions were held with relevant parties or stakeholders, including employees of the Directorate General of Fisheries at the Ministry of Agriculture, Gazan fishermen, and some of the Gazan public on the beach to fill the necessary gaps in collecting data related to sea turtle sightings, strandings, captures, and bycatch. In addition, the author tracked and reviewed local media reports and social media related to sea turtles. On many occasions, the author was contacted by fishermen or other Gazans via mobile phones or social media, including WhatsApp and Facebook, to inquire about the species of sea turtles they encountered at sea or on the beach, whether alive or dead. Under certain conditions, the author was able to take approximate measurements and available observations on some specimens he encountered on the beach. Finally, digital cameras were used throughout the study to take photographs for documentation and verification purposes.

Results

Description of by-caught and stranded Leatherback Sea Turtles

Leatherback Sea Turtles are unique and recognized by scientific circles, the Directorate General of Fisheries at the Ministry of Agriculture, and Gazan fishermen for their relatively large sizes, dark colors, and the absence of scales or plates on their carapaces. They have pinkish-white coloring on their plastrons. In this way, they do not resemble the Loggerhead and Green Sea Turtles known in the Gaza Strip. Perhaps what draws attention, despite their rarity in being by-caught in fishing nets or stranded, is the presence of 7 distinct ridges extending along their carapaces. In fact, most of the few individuals that have been found, whether alive or dead, had upper shells or carapaces longer than 90 cm. Compared to the Green and Loggerhead Sea Turtles of the Gaza Strip, Leatherbacks have relatively longer forelimbs and paddle-shaped hind flippers. Claws are absent from both pairs of flippers.

Strandings of Live and Dead Leatherback Sea Turtles

Stranded sea turtles are those that a person may find on the beach or floating, alive or dead. If they are alive, they are most likely in a weak state and may be sick or injured. It is worth noting here that there are no centers or facilities in the Gaza Strip for the treatment and rehabilitation of live turtles. Leatherbacks are the rarest species of sea turtle that have washed up, dead or alive, on the 42-km-long shore of the Gaza Strip (Figure 2). Many stakeholders believed that the dead Leatherbacks that washed up on the beaches died from diseases or injuries resulting from fisheries by-catch, collisions with fishing vessels, or from ingesting floating plastic bags or debris mistaken for their favorite food; jellyfish which are numerous in the Mediterranean coast of the Gaza Strip. They did not hide the danger of Leatherbacks getting entangled in damaged or abandoned fishing nets at sea, as they wrap around their necks, fins, and the rest of their bodies, causing them to become sick or suffocate, eventually leading to death. Each year, one or two adult or sub-adult specimens are by-caught or stranded on the beaches of the Gaza Strip. According to field observations by the researcher, fishermen and related parties, some of the carcasses found were badly decomposed. No one in the Gaza Strip has reported finding small specimens of this species, attributing this to its rarity and lack of reproduction in the area.

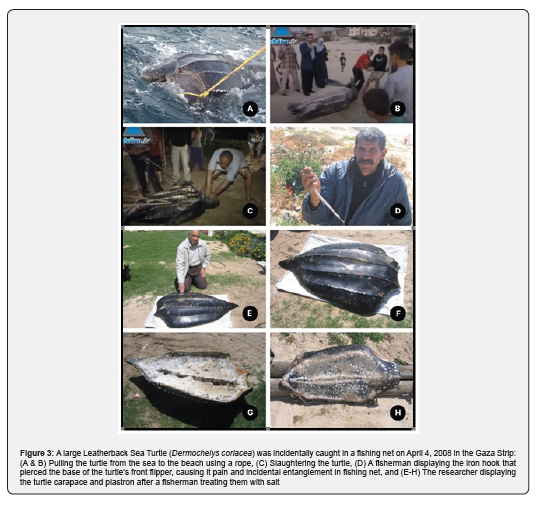

The story of slaughtering and eating the Leatherback Sea Turtle in the Gaza Strip: A painful scene was broadcast on TV and websites

A large Leatherback Sea Turtle was by-caught in the Mediterranean Sea waters south of the fishing port of Gaza City at 6 p.m. on Thursday, April 4, 2008, 200-300 meters from the shore (Figure 3). The turtle was incidentally caught in a sardine net belonging to a Gazan fisherman. The hasakas (small fishing boats) dragged it to the crowded beach. The turtle was tied to a rope and then dragged a little further from the shoreline. The fishermen reported that the turtle was exhausted as a result of the net threads being wrapped around its neck. More seriously, an iron hook (which has no equivalent in the Gaza Strip, but is used by Egyptian fishermen, indicating that the turtle had come from Egyptian sea waters) was found penetrating the base of its front flipper, causing it severe pain and exhaustion, which, according to the fishermen, led to its capture in the fishing net. The fishermen reported that the weight of the turtle exceeded 300 kg, and according to estimates made on the turtle’s carapace and plastron, the length of the turtle from the top of its head to the top of its tail was about 170 cm. An old fisherman dragged it behind a truck, flipped it on its back, and then slaughtered it from the neck, in this most painful scene that was shown repeatedly on television screens and websites. The turtle’s meat was then distributed to about 20 Palestinian families of relatives or neighbors to eat. One of the fishermen present in the crowd explained to the media that sea turtle meat is delicious and that its blood helps in treating various diseases, including tremors and sexual weakness. The day after the turtle was slaughtered, the researcher visited the fisherman whose net had incidentally caught the turtle, and found the turtle's shell (carapace and plastron) treated with salt to preserve it.

Local consumption of Leatherbacks

Apart from the real and truly painful story mentioned earlier about the slaughter and eating the flesh of the Leatherback in the Gaza Strip, and given the rarity of these turtles in the coastal ecosystem of the Gaza Strip, no fisherman or concerned parties reported any other consumption of Leatherback meat by Gazans, and since they do not nest in the area, there is no pursuit of their eggs. In contrast, live specimens of Loggerhead and Green Sea Turtles have been found being sold and/or slaughtered in some fish markets in the Gaza Strip for meat consumption. In general, those who eat these creatures describe their meat as delicious, and some parts of the turtles may be a cure for some diseases. Some Gazans claimed that sea turtle blood has a Viagra-like effect and stimulates erectile dysfunction in some people.

Local threats facing Leatherbacks in the Gaza Strip

In the Gaza Strip, despite its small area (365 km2) and limited coastline (42 km) on the Mediterranean Sea, there are many threats facing Leatherbacks and other species of sea turtles, as follows:

Fisheries bycatch (bycatch in fishing gear): Sea turtle bycatch is a worldwide problem. A large number of sea turtle species (Loggerhead, Green, and Leatherback Sea Turtles) being incidentally caught and dying every year in the Gaza Strip as a result of being caught in gillnets, trawls, longlines, and other gear forms. In fact, this unintended capture in fishing gear can result in drowning or cause injuries that lead to death or debilitation. Among sea turtles, Leatherbacks are the least by-caught species due to its low occurrence in the coastal waters of the Gaza Strip.

Vessel strikes: Watercraft strikes pose a major threat to endangered sea turtles, especially those living on or near the surface, resulting in injury or death. In fact, the reason for the death or injury of many sea turtles stranded on the beaches of the Gaza Strip may be their collision with Gazan fishing boats or even Israeli naval boats deployed in the sea and near the coasts of the Gaza Strip for security reasons, as they always claim. It is noteworthy that the marine ecosystem and fishing ports in the Gaza Strip are full of more than 1,500 fishing vessels of different sizes and functions, consisting of six types: Trawlers (gar), large purse seiners (shanshula), small purse seiners (shanshula), hasakas with motor, feluccas, and hasakas with oars.

Harvest for consumption

Some Gazans, especially fishermen, may buy sea turtles or use what they catch in their fishing gear to eat, and sometimes obtain their shells for decorative purposes. Over the past two decades, some local media outlets have reported the consumption of small quantities of sea turtles for their meat, especially in light of the Israeli blockade imposed on the Gaza Strip since 2007, and the wars waged by Israel from time to time. Of course, no one can talk about the consumption of sea turtle meat in the Gaza Strip without mentioning the unique incident of the slaughter of a large Leatherback in April 2008 in public and in front of cameras. Short videos were recorded of the same event (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ncwEX2nKEwA). Among the media coverage of the event were the following news headlines:

· Rare Giant Turtle Killed in Gaza (April 4, 2008), (https://www.dumpert.nl/item/72311_727d575a).

· Slaughtered Leatherback in Gaza (April 5, 2008), (http://www.turtleforum.com/forum/upload/index.php?/forums/topic/89103-slaughtered-leatherback-in-gaza/).

· Gazans Eat Endangered Turtle "As Good As Viagra" (April 7, 2008), (http://www.indiaenvironmentportal.org.in/content/245349/gazans-eat-endangered-turtle-as-good-as-viagra/).

·

Marine pollution and debris: The increasing pollution and debris of near- and far-off-shore marine habitats threatens all sea turtles and leads to the degradation of their habitats in the marine ecosystem of the Gaza Strip. Most of the wastewater produced in the Gaza Strip is discharged into the marine environment, carrying organic matter, toxins, chemicals and solid wastes, including hazardous and non-biodegradable plastic wastes. Some toxins can accumulate and enter food chains and webs of which sea turtles may be an important part. Gazans believe that plastic wastes - as part of marine pollution - pose a threat to sea turtles, as these creatures may swallow plastic materials or bags by mistake, thinking they are jellyfish, and they become sick, suffocate and die. Plastic pieces can rip through their stomachs, causing internal lesions. Sea turtles may also become entangled with marine debris resulting from abandoned or lost fishing gear, especially nets and ropes in the sea, due to the Israeli occupation’s pursuit and bombing of Gazan fishermen’s fishing equipment while they are carrying out their mission at sea, which also cause their death.

Climate change: Leatherbacks do not nest in the Gaza Strip. Climate change remains a major threat to nesting and nest destruction worldwide. However, changes in marine environmental temperatures are likely to alter the abundance and distribution of food resources (jellyfish and other soft-bodied organisms) for Leatherbacks, resulting in a shift in their migration and foraging range.

Discussion

The Leatherback Sea Turtle (Dermochelys coriacea) is the world's largest living turtle and is globally classified as “Vulnerable” (VU) by IUCN [38]. Leatherbacks appear to be widely distributed throughout the Mediterranean, from the Strait of Gibraltar to the far eastern part, and enter the Mediterranean at a relatively large size, with no evidence of their breeding in the Mediterranean [39,40]. The descriptions of the turtle shown in the current study are similar to those drawn by many international studies and publications in terms of size, morphology, color and other aspects [41-45]. Various local media outlets always describe rare sightings and strandings of such Leatherbacks (and other species of giant sea turtles), whether alive or dead, as strange events occurring in the sea waters or on the beaches of the Gaza Strip. In fact, Leatherbacks are the third most common sighted or stranded sea turtle in the Gaza Strip as well as the Palestinian and Egyptian coasts after Loggerheads and Green Sea Turtles [46-48]. The inclusion of the three species of turtles will raise awareness of them in the Gaza Strip and may pave the way for identifying other species that may visit marine waters or strand on the beaches of the Gaza Strip in the coming days or years. This is not unlikely, of course, as many marine waters and beaches in the area have witnessed recordings of live or dead specimens of other species of sea turtles [49,50]. A clear example is the Flatback Sea Turtle (Natator depressus), which is not a local Mediterranean species, was pointed out by many Israeli fishermen in the basin.

The majority of sea turtles that have stranded on the beaches of the Gaza Strip over the past two decades have been Loggerheads, followed by Greens in much smaller numbers. Leatherbacks are rare in Palestinian marine waters and therefore strand less frequently. However, most strandings of all species have been caused by bycatch, suffocation due to ingestion of plastic, entanglement in marine debris such as damaged or abandoned nets, or collisions with fishing boats. Some of the injuries sustained by some sea turtles suggest that they may have been deliberately killed by Gazan fishermen when they were incidentally caught in fishing gear or violently collided with fishing boats (Personal Communications). Similar explanations were proposed by Belmahi et al [16], Poppi et al. [51], and Vélez-Rubio et al. [52], who found that stranding of injured sea turtles was the result of bycatch by artisanal fisheries or collisions with fishing vessels. The trade in sea turtles of all kinds in the Gaza Strip is not large, but rather very small and does not attract much attention. Leatherbacks have never been traded in the Gaza Strip, due to their low population in the Mediterranean compared to Loggerheads or Greens, and low incidence of bycatch or stranding. Globally, Greens and Hawksbills are considered valuable reptiles because of their meat, shells and skins, some of which are used commercially in the manufacture of statues, jewelry and furniture inlay, as Frazier [53] pointed out. In Egypt, a country closer to Palestine, there has been a market trade in a variety of sea turtle species, including Leatherbacks, for human consumption and this trade is a major concern [54-58]. Sea turtle trade for consumption or other uses has also been reported in various countries around the world as shown by several recent studies [59-63].

The painful scene of a large Leatherback being slaughtered on the Gaza City beach in front of a crowd of Gazans in April 2008, which was broadcast on television and websites, was not repeated with other Leatherbacks. It is worth noting that the meat of this species is very oily and not particularly preferred for human consumption [64]. But unfortunately, the event was politically and culturally exaggerated, as if it were a tsunami that struck and killed sea turtles in the Gaza Strip. Sea turtles, including Leatherbacks, are widely slaughtered and consumed by people around the world as reported in publications [65-68]. The slaughter of the Leatherback in April 2008 in the Gaza Strip received wide comments from Palestinians and foreigners who watched the video of the giant turtle being slaughtered, condemning this act against the rarest creatures on Earth. In fact, sea turtles are slaughtered and consumed in many countries around the world, including the developing and developed ones, where sea turtle products such as meat, fatty tissue, organs, blood, and eggs are common food items, despite national regulations in some countries that prohibit such consumption [69-71]. The truth is that the Palestinians’ keenness to preserve wildlife has had many bright aspects in the return of sea turtles and terrestrial creatures to their ecological habitats in the Gaza Strip and all of Palestine. Despite all this, no one can blame a people occupied and besieged by Israel, and against whom Israel wages wars from time to time, for hunting creatures in their terrestrial or marine environments to satisfy their hunger in light of the famine and economic and social conditions experienced by the people of the Gaza Strip. Many videos and news have spread showing the return of live sea turtles to the sea after being by-caught or washed up on the shores of the Gaza Strip in recent years. Where are these commentators from these positive signals, or are these biased people looking at the glass half empty and ignoring the half full?

The reason for the incidental capture of the Leatherback of the previous story was an iron hook, different in shape and size from the hooks used by Gazan fishermen, which pierced one of the turtle’s front flippers, causing injuries, which pushed the turtle closer to the shore and eventually became entangled in a fishing net. In fact, bycatch in commercial fishing gear such as nets, longlines, and hooks has been identified as a known cause of injury and/or death for many sea turtle species worldwide [72]. Dodge et al. [73], Hamelin et al. [74] and Dunn et al. [75] pointed out that pelagic longline fisheries including hooks pose a threat to Leatherbacks during their trans‐oceanic pelagic migrations and in offshore foraging areas at the global level. Lewison et al. [12] estimated that more than 50,000 Leatherbacks were taken as by-catch in pelagic longline fisheries in 2000. To reduce sea turtle mortality, Read [76] suggested the use of circle hooks in pelagic longlines, as good results have been achieved. The coastal Gaza Strip is not isolated from the coastal countries of the world in terms of the threats facing sea turtles, including Leatherbacks, which are rarely recorded as living or dead specimens in marine waters or on the 42-km-long beach. In fact, bycatch poses a major threat to sea turtles, leading to their capture or death. Bycatch using bottom trawls, driftnets, purse seines and longlines is not only a problem in the Gaza Strip, but is a global problem that threatens many endangered species including sea turtles worldwide. This is evident from the large number of studies that have shown the risks of bycatch of sea turtles, especially Leatherback Sea Turtles, around the world [77-87]. No one can deny the role of Palestinian (and possibly Israeli) boats stationed off the coast of the Gaza Strip in colliding with sea turtles, leading to injuries, deaths and strandings. This is a matter known worldwide, as global studies have indicated the dangers of boat collisions to the lives and health of sea turtles [88-93]. Sea turtles can be directly affected by marine debris [94,95], as they may swallow nylon bags thinking they are jellyfish, which harm their health and may kill them, as previous local studies in the Gaza Strip have indicated. If this is true for most species of sea turtles, it is even more accurate for Leatherbacks, which feed primarily on jellyfish [96-98].

Sea turtles entangled in plastic debris from damaged fishing gear, ropes or hooks are a reality in fragile marine environments such as those in the Gaza Strip. The researcher’s trips to the open sea have proven this to be true, with some fishermen resorting to throwing damaged nets into the sea (Personal Observations). Israeli pursuits of fishermen at sea by boats and corvettes also result in the destruction of fishing nets and boats, which are forcibly left at sea and can pose a serious threat to endangered marine creatures including turtles. In fact, many international studies seem to agree with this painful scene in the Gaza Strip, and confirm the danger of marine debris in all its forms to marine life, especially Leatherbacks [99-103]. Finally, in light of the threats facing sea turtles in general in the Gaza Strip, the study recommends the need to protect them as creatures that deserve life in addition to being globally threatened. In addition, sea turtles, especially Leatherbacks, are known as natural enemies and predators of jellyfish, and their numbers, which the Gazans suffer from, can be controlled.

References

- D Margaritoulis, A Demetropoulos (Eds.) (2001) The status of marine turtles in the Mediterranean. Proceedings of the First Mediterranean Conference on Marine Turtles. Barcelona Convention-Bern Convention-Bonn Convention (CMS) Nicosia, Cyprus 51-61.

- Stewart K, Johnson C, Godfrey MH (2007) The minimum size of Leatherbacks at reproductive maturity, with a review of sizes for nesting females from the Indian, Atlantic and Pacific Ocean basins. The Herpetological Journal 17(2):123-128.

- Zug GR & Parham JF (1996) Age and growth in Leatherback Turtles, Dermochelys coriacea (Testudines: Dermochelyidae): A skeletochronology analysis. Chelonian Conservation and Biology 2(2): 244-249.

- Chen IH, Yang W, Meyers MA (2015). Leatherback Sea Turtle shell: A tough and flexible biological design. Acta Biomaterialia 28: 2-12.

- Houghton JDR, Doyle TK, Davenport J, Wilson RP and Hays GC (2008) The role of infrequent and extraordinary deep dives in Leatherback Turtles (Dermochelys coriacea). Journal of Experimental biology, 211(16): 2566–2575.

- Milagros LM, Rocha CFD, Wallace ADBP, Miller P (2009): Prolonged deep dives by the Leatherback Turtle Dermochelys coriacea: Pushing their aerobic dive limits, Marine Biodiversity Records 2: 2–3.

- James MC, Herman TB (2001) Feeding of Dermochelys coriacea on medusae in the northwest Atlantic. Chelonian Conservation Biology, Lunenburg 4(1): 202-205.

- Houghton, J.D.R., Doyle, T.K., Wilson, M.W., Davenport, J. and Hays, G.C. (2006): Jellyfish Aggregations and Leatherback Turtle Foraging Patterns in a Temperate Coastal Environment. Ecology 87(8): 1967-1972.

- Graham TR, Harvey JT, Benson SR, Renfree JS, Demer DA (2010) The acoustic identification and enumeration of scyphozoan jellyfish, prey for Leatherback Sea Turtles (Dermochelys coriacea), off central California. ICES Journal of Marine Science 67(8): 1739-1748.

- Schuyler Q, Hardesty BD, Wilcox C, Townsend K (2014) Global analysis of anthropogenic debris ingestion by sea turtles. Conservation Biology 28(1): 129-139.

- James MC, Andrea Ottensmeyer C, Myers RA (2005) Identification of high‐use habitat and threats to Leatherback Sea Turtles in northern waters: new directions for conservation. Ecology Letters 8(2): 195-201.

- Lewison RL, Freeman SA, Crowder LB (2004) Quantifying the effects of fisheries on threatened species: The impact of pelagic longlines on Loggerhead and Leatherback Sea Turtles. Ecology letters 7(3): 221-231.

- Dudley PN, Porter WP (2014) Using empirical and mechanistic models to assess global warming threats to Leatherback Sea Turtles. Marine Ecology Progress Series 501: 265-278.

- Guimaraes SM, Tavares DC, Monteiro-Neto C (2018) Incidental Capture of Sea Turtles by Industrial Bottom Trawl Fishery in the Tropical South-Western Atlantic. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom 98(6): 1525-1531.

- Lynch JM (2018) Quantities of marine debris ingested by sea turtles: Global meta-analysis highlights need for standardized data reporting methods and reveals relative risk. Environmental Science & Technology 52(21): 12026-12038.

- Belmahi AE, Belmahi Y, Benabdi M, Bouziani AL, Darna SA et al., (2020) First study of sea turtle strandings in Algeria (western Mediterranean) and associated threats: 2016–2017. Herpetozoa 33: 113-120.

- Keznine M, Benaissa H, Oubahaouali B, Barylo Y, Loboiko Y et al., (2022). Preliminary data on bycatch and stranding of marine turtles in Al Hoceima, Morocco. Egyptian Journal of Aquatic Biology & Fisheries 26(2):253-261.

- Mghili B, Benhardouze W, Aksissou M, Tiwari M (2023) Sea turtle strandings along the Northwestern Moroccan coast: Spatio-temporal distribution and main threats. Ocean & Coastal Management, 237: 106539.

- Camiñas JA (1998) Is the Leatherback (Dermochelys coriacea Vandelli, 1761) a permanent species in the Mediterranean Sea. Rapp. Comm. Int. Mer Medit 35: 388-389.

- Taşkavak E, Boulon RH, Atatür MK (1998) An unusual stranding of a Leatherback Turtle in Turkey. Marine Turtle Newsletter 80(13).

- Taşkavak E, Akçınar SC, İnanlı Ç (2015) Rare occurrence of the Leatherback Sea Turtle, Dermochelys coriacea, in Izmir Bay, Aegean Sea, Turkey. Ege Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 32(1): 51-52.

- Campbell A, Clarke M, Ghoneim S, Hameid WS, Simms C, et al., (2001) On status and conservation of marine turtles along the Egyptian Mediterranean Sea coast: Results of the Darwin Initiative Sea Turtle Conservation Project 1998–2000. Zoology in the Middle East, 24(1): 19-29.

- Ergene S, Uçar AH (2017) A Leatherback Sea Turtle entangled in fishing net in Mersin Bay, Mediterranean Sea, Turkey. Marine Turtle Newsletter (153): 4-6.

- Ibrahim A A (2001) The reptile community of the Zaranik protected area, North Sinai, Egypt with special reference to their ecology and conservation. Egyptian Journal of Natural History 3(1):81-92.

- Levy Y, King R, Aizenberg I (2005) Holding a live Leatherback Turtle in Israel: Lessons learned. Marine Turtle Newsletter, 107: 7-8.

- Sönmez B, Sammy D, Yalçın-Özdilek Ş, Gönenler ÖA, Açıkbaş U, et al., (2008) A stranded Leatherback Sea Turtle in the Northeastern Mediterranean, Hatay, Turkey. Marine Turtle Newsletter 119: 12-13.

- Karaa S, Bradai MN, Mahmoud S, Jribi I (2016) Migration of the Mediterranean Sea turtles into the Tunisian waters, importance of the tag recoveries as conservation management method. Marine Biology Notebook 57: 103-111.

- Karaa S, Jribi I, Bouain A, Girondot M, Bradai MN (2013). On the occurrence of Leatherback Turtles Dermochelys coriacea (Vandelli, 1761). Tunisian waters (Central Mediterranean Sea). Herpetozoa 26(1/2): 65-75.

- Bauer AM, DeBoer JC, Taylor DJ (2017) Atlas of the Reptiles of Libya. Proc. Cal. Acad. Sci, 64(8): 155-318.

- Masski H, Tai I (2017) Exceptional leatherback turtle stranding event in the Moroccan Atlantic during 2015. Marine Turtle Newsletter (153): 11-12.

- Candan O, Canbolat AF (2018) New record of a Leatherback (Dermochelys coriacea) stranding in Turkey. Biharean Biol 12(1): 56-57.

- Abd Rabou AN (2013) Priorities of scientific research in the fields of marine environment and fishery resources in the Gaza Strip – Palestine. Priorities of Scientific Research in Palestine 481-522.

- Abd Rabou AN, Elkahlout KE, Elnabris KJ, Attallah AJ, Salah JY et al., (2023) An inventory of some relatively large marine mammals, reptiles and fishes sighted, caught, by-caught or stranded in the Mediterranean coast of the Gaza Strip – Palestine. Open Journal of Ecology (OJE) 13(2): 119-153.

- Al-Rabi A, Abd Rabou AN, Musleh R (2023) Marine Environment and Coast (Mediterranean and Dead Sea), Chapter 8 (p.p. 278 – 334). In: State of the Environment Report in the State of Palestine 2023 (Ed. Environment Quality Authority – EQA, 2023), Ramallah, Palestine, 500.

- Abd Rabou AN, Yassin MM, Saqr TM, Madi AS, El-Mabhouh FA (2007) Threats facing the marine environment and fishing in the Gaza Strip: Field and literature study. Theme XII: Environmental Design Trends and Pollution Control, The 2nd International Engineering Conference on Construction and Development (IECCD-II), Islamic University of Gaza, Gaza Strip, Palestine, September 3-4, 2007, 11-31.

- UNEP (2003) Desk Study on the Environment in the Occupied Palestinian Territories. United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) Nairobi 188.

- Abd Rabou AN (2019) On the Occurrence and Health Risks of the Silver-Cheeked Toadfish (Lagocephalus sceleratus Gmelin, 1789) in the Marine Ecosystem of the Gaza Strip-Palestine. Biodiversitas, 20(9): 2618-2625.

- McClain CR, Balk MA, Benfield MC, Branch TA, Chen C, et al., (2015): Sizing ocean giants: Patterns of intraspecific size variation in marine megafauna. Peer J 3: e715.

- Casale P, Nicolosi P, Freggi D, Turchetto M, Argano R (2003) Leatherback Turtles (Dermochelys coriacea) in Italy and in the Mediterranean basin. Herpetological Journal 13(3): 135-140.

- Levy Y, Frid O, Weinberger A, Sade R, Adam Y, et al., (2015) A small fishery with a high impact on sea turtle populations in the eastern Mediterranean. Zoology in the Middle East 61(4): 300-317.

- Frazier J, Salas S (1984) The status of marine turtles in the Egyptian Red Sea. Biological conservation 30(1)

: 41-67. - Bariche M (2012) Field Identification Guide to the Living Marine Resources of the Eastern and Southern Mediterranean. Food & Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) Rome 610.

- IUCN (2012) Marine Mammals and Sea Turtles of the Mediterranean and Black Seas. IUCN, Gland.

- Capula M (1989) Simon and Schuster’s guide to reptiles and amphibians of the world. Simon and Schuster Inc., 256.

- IAC Secretariat (2004) An Introduction to the Sea Turtles of the World. Pro Tempore Secretariat of the Inter-American Convention for the Protection and Conservation of Sea Turtles (IAC), San José, Costa Rica.

- Clarke M, Campbell AC, Hameid WS, Ghoneim S (2000) Preliminary report on the status of marine turtle nesting populations on the Mediterranean coast of Egypt. Biological Conservation 94(3): 363-371.

- Clarke M, Campbell AC (2003) Identification of Marine Turtle Nesting Beaches on the Mediterranean Coast of Sinai, Egypt. Herpetological Review 34(3): 206-209.

- Sassoon S (2024) Spatiotemporal Habitat Use and Behavior of Sea Turtles in the Southeastern Mediterranean: Comparative Analysis of Nesting and Rehabilitated Individuals Using Satellite Tracking Data. M.Sc. Thesis, Department of Marine Biology, University of Haifa, Israel, 80 pp.

- Tomás J, Raga JA (2008) Occurrence of Kemp's Ridley Sea Turtle (Lepidochelys kempii) in the Mediterranean. Marine Biodiversity Records 1: e58.

- Revuelta O, Carreras C, Domènech F, Gozalbes P, Tomás J (2015) First report of an Olive Ridley (Lepidochelys olivacea) inside the Mediterranean Sea. Mediterranean Marine Science 16(2): 346-351.

- Poppi L, Zaccaroni A, Pasotto D, Dotto G, Marcer F, et al., (2012) Post-mortem investigations on a Leatherback Turtle Dermochelys coriacea stranded along the Northern Adriatic coastline. Diseases of Aquatic Organisms 100(1): 71-76.

- Vélez-Rubio GM, Prosdocimi L, López-Mendilaharsu M, Caraccio MN, Fallabrino A et al., (2023) Natal origin and spatiotemporal distribution of Leatherback Turtle (Dermochelys coriacea) strandings at a foraging hotspot in temperate waters of the Southwest Atlantic Ocean. Animals, 13(8): 1285.

- Frazier J (2003) Prehistoric and ancient historic interactions between humans and marine turtles. In: The Biology of Sea Turtles, Volume II. P.L. Lutz, J.A. Musick and J. Wyneken (Eds). CRC Press, Boca Raton, 1-38.

- Venizelos L, Nada MA (2000) Exploitation of Loggerhead and Green Turtles in Egypt: Good news? Marine Turtle Newsletter, 87: 12-13.

- Nada MA (2001) Observations on the trade in sea turtles at the fish market of Alexandria, Egypt. Zoology in the Middle East, 24(1): 109-118.

- Nada MA (2002) Status of the sea turtle trade in Alexandria's fish market. Marine Turtle Newsletter 95: 5-8.

- Nada M, Casale P (2011) Sea turtle bycatch and consumption in Egypt threatens Mediterranean turtle populations. Oryx, 45(1): 143-149.

- Boura L, Abdullah SS, Nada MA (2016) New observations of sea turtle trade in Alexandria, Egypt. A report by MEDASSET - Mediterranean Association to Save the Sea Turtles 27.

- Barreiros JP, Barcelos J (2001) Plastic Ingestion by a Leatherback Turtle (Dermochelys coriacea). Marine Pollution Bulletin 42(11): 1196-1197.

- Hancock JM, Furtado S, Merino S, Godley BJ, Nuno A (2017) Exploring drivers and deterrents of the illegal consumption and trade of marine turtle products in Cape Verde, and implications for conservation planning. Oryx 51(3): 428-436.

- Gomez L, Krishnasamy K (2019) A Rapid Assessment on the Trade in Marine Turtles in Indonesia, Malaysia and Viet Nam. TRAFFIC. Petaling Jaya, Malaysia 74

- Rothamel E, Rasolofoniaina BJR, Borgerson C (2021) The effects of sea turtle and other marine megafauna consumption in northeastern Madagascar. Ecosystems and People, 17(1): 590-599.

- Lopes LL, Paulsch A, Nuno A (2022) Global challenges and priorities for interventions addressing illegal harvest, use and trade of marine turtles. Oryx 56(4): 592-600.

- Kemf E, Groombridge B, Abreu A, Wilson A (2000) Marine turtles in the wild. Published by WWF – World Wide Fund for Nature (formerly World Wildlife Fund), Gland, Switzerland 20 pp.

- Suarez M, Starbird C (1995) A traditional fishery of Leatherback Turtles in Maluku, Indonesia. Marine Turtle Newsletter, 68: 15-18.

- Jones TT, Bostrom BL, Hastings MD, Van Houtan KS, Pauly D et al., (2012) Resource Requirements of the Pacific Leatherback Turtle Population. PLoS ONE 7(10): e45447.

- Williams J (2017) Illegal take and consumption of Leatherback Sea Turtles (Dermochelys coriacea) in Madagascar and Mozambique. Africa Sea Turtle Newsletter 7: 25-33.

- Gunawan A (2019) Hunted for its meat; 213-kg Leatherback Turtle slaughtered in North Sumatra. The Jakarta Post.

- Aguirre AA, Gardner SC, Marsh JC, Delgado SG, Limpus CJ et al., (2006): Hazards associated with the consumption of sea turtle meat and eggs: a review for health care workers and the general public. Eco Health 3: 141-153.

- Garland KA, Carthy RR (2010) Changing taste preferences, market demands and traditions in Pearl Lagoon, Nicaragua: A community reliant on Green Turtles for income and nutrition. Conservation and Society 8(1): 55-72.

- Semmouri I, Janssen CR, Asselman J (2024) Health risks associated with the consumption of sea turtles: A review of chelonitoxism incidents and the presumed responsible phycotoxins. Science of the Total Environment 954: 176330.

- Wallace B, Kot C, DiMatteo A (2013): Impacts of fisheries bycatch on marine turtle populations worldwide: Toward conservation and research priorities. Ecosphere 4(3): 1-49.

- Dodge KL, Galuardi B, Miller TJ, Lutcavage ME (2014) Leatherback turtle movements, dive behavior, and habitat characteristics in ecoregions of the Northwest Atlantic Ocean. PloS ONE 9(3): e91726.

- Hamelin KM, James MC, Ledwell W, Huntington J, Martin K (2017) Incidental capture of Leatherback Sea Turtles in fixed fishing gear off Atlantic Canada. Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems 27(3): 631-642.

- Dunn MR, Finucci B, Pinkerton MH, Sutton P, Duffy CA (2023) Increased captures of the critically endangered Leatherback Turtle (Dermochelys coriacea) around New Zealand: The contribution of warming seas and fisher behavior. Frontiers in Marine Science 10: 1170632.

- Read AJ (2007) Do circle hooks reduce the mortality of sea turtles in pelagic longlines? A review of recent experiments. Biological conservation 135(2): 155-169.

- Jribi I, Bradai MN, Bouain A (2007) Impact of trawl fishery on marine turtles in the Gulf of Gabes, Tunisia. Herpetological Journal 17(2): 110-114.

- Jribi I, Echwikhi K, Bradai MN, Bouain A (2008) Incidental capture of sea turtles by longlines in the Gulf of Gabes (South Tunisia): a comparative study between bottom and surface longlines. Scientia Marina, 72(2): 337-342.

- Crognale MA, Eckert SA, Levenson DH, Harms CA (2008) Leatherback Sea Turtle Dermochelys coriacea visual capacities and potential reduction of bycatch by pelagic longline fisheries. Endangered Species Research 5(2-3): 249-256.

- Casale P (2011) Sea turtle by‐catch in the Mediterranean. Fish and Fisherie 12(3): 299-316.

- Roe JH, Morreale SJ, Paladino FV, Shillinger GL, Benson SR et al., (2014) Predicting bycatch hotspots for endangered Leatherback Turtles on longlines in the Pacific Ocean. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 281(1777): 20132559.

- Senko J, White ER, Heppell SS, Gerber LR (2014) Comparing bycatch mitigation strategies for vulnerable marine megafauna. Animal Conservation 17(1):5-18.

- Stewart KR, La Casella EL, Roden SE, Jensen MP, Stokes LW, Epperly SP, Dutton PH (2016) Nesting population origins of Leatherback Turtles caught as bycatch in the US pelagic longline fishery. Ecosphere 7(3): e01272.

- Blades DC, Walcott J, Horrocks JA (2019) Leatherback bycatch in an eastern Caribbean artisanal longline fishery. Endangered Species Research 40: 329-335.

- Dodge KL, Landry S, Lynch B, Innis CJ, Sampson K, et al., (2022) Disentanglement network data to characterize Leatherback Sea Turtle Dermochelys coriacea bycatch in fixed-gear fisheries. Endangered Species Research 47: 155-170.

- Ortega AA, Mitchell NJ, Marn N, Shillinger GL (2024) A systematic review protocol for quantifying bycatch of critically endangered Leatherback Sea Turtles within the Pacific Ocean basin. Environmental Evidence 13(1): 27.

- Griffiths SP, Wallace BP, Cáceres V, Rodríguez LH, Lopez J et al., (2024) Vulnerability of the Critically Endangered Leatherback Turtle to fisheries bycatch in the eastern Pacific Ocean. II. Assessment of mitigation measures. Endangered Species Research 53: 295-326.

- Hazel J, Gyuris E (2006) Vessel-related mortality of sea turtles in Queensland, Australia. Wildlife Research 33(2): 149-154.

- Hazel J, Lawler IR, Marsh H, Robson S (2007) Vessel speed increases collision risk for the Green Turtle Chelonia mydas. Endangered Species Research 3(2): 105-113.

- Archibald DW, James MC (2018) Prevalence of visible injuries to Leatherback Sea Turtles Dermochelys coriacea in the Northwest Atlantic. Endangered Species Research 37: 149-163.

- Dourdeville KM, Wynne S, Prescott R, Bourque O (2018) Three-Island, Intra-Season Nesting Leatherback (Dermochelys coriacea) Killed by Vessel Strike off Massachusetts, USA. Marine Turtle Newsletter 155: 8-11.

- Fuentes MM, Meletis ZA, Wildermann NE, Ware M (2021) Conservation interventions to reduce vessel strikes on sea turtles: A case study in Florida. Marine Policy 128: 104471.

- Welsh RC, Witherington BE (2023) Spatial mapping of vulnerability hotspots: Information for mitigating vessel-strike risks to sea turtles. Global Ecology and Conservation 46: e02592.

- Bugoni L, Krause L, Petry MV (2001) Marine debris and human impacts on sea turtles in southern Brazil. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 42(12): 1330-1334.

- Casale P, Freggi D, Paduano V, Oliverio M (2016) Biases and Best Approaches for Assessing Debris Ingestion in Sea Turtles, with a Case Study in the Mediterranean. Marine Pollution Bulletin 110(1): 238-249.

- Mrosovsky N, Ryan GD, James MC (2009) Leatherback Turtles: The menace of plastic. Marine Pollution Bulletin 58(2): 287-289.

- Dodge KL, Logan JM, Lutcavage ME (2011) Foraging ecology of Leatherback Sea Turtles in the Western North Atlantic determined through multi-tissue stable isotope analyses. Marine Biology 158: 2813-2824.

- Heaslip SG, Iverson SJ, Bowen WD, James MC (2012) Jellyfish support high energy intake of Leatherback Sea Turtles (Dermochelys coriacea): video evidence from animal-borne cameras. PloS one 7(3): e33259.

- Schuyler QA, Wilcox C, Townsend K, Hardesty BD, Marshall NJ (2014) Mistaken identity? Visual similarities of marine debris to natural prey items of sea turtles. Bmc Ecology 14: 14.

- Darmon G, Miaud C, Claro F, Doremus G, Galgani F (2017) Risk assessment reveals high exposure of sea turtles to marine debris in French Mediterranean and metropolitan Atlantic waters. Deep Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography 141: 319-328.

- Blais N, Wells PG (2022) The Leatherback Turtle (Dermochelys coriacea) and plastics in the Northwest Atlantic Ocean: A hazard assessment. Heliyon 8(12): e12427.

- Mghili B, Keznine M, Analla M, Aksissou M (2023) The impacts of abandoned, discarded and lost fishing gear on marine biodiversity in Morocco. Ocean & Coastal Management 239

- Deguchi S, Ueno S, Kodera H, Fujino Y, Kongou H et al., (2025) Accidental ingestion of largest marine debris by a Leatherback Turtle. Marine Pollution Bulletin 211: 117406.