The Bengal Tigers of India

Jai S Ghosh*

Department of Biotechnology, Smt. K.W. College, Sangli, India

Submission: July16, 2020; Published: August 17, 2020

*Corresponding author: Jai S. Ghosh, Department of Biotechnology, Smt. K. W. College, Sangli 416416 India

How to cite this article: Jai S Ghosh. The Bengal Tigers of India. JOJ Wildl Biodivers. 2020: 2(5): 555597. DOI: 10.19080/JOJWB.2020.02.555597

Abstract

The Bengal tigers (Panthera Tigris Tigris) are unique to India and Bangladesh. They are usually found in the mangrove forest of India and Bangladesh especially in the Gangetic delta region of both these countries. They have many unique characteristics like they are great swimmers and can catch their prey in water. With the rapid destruction of the mangroves, attempts are made to create reserve forests which do not have either a river or mangroves plantation.

Introduction

The Bengal tiger (Panthera tigris tigris) often called as the Royal Bengal Tigers, is a special breed of the population and very unique to the Indian subcontinent (which include Bangladesh, Nepal and Bhutan and of course the Gangetic West Bengal) [1]. It is a strict carnivore and its population is dwindling due to excessive poaching. Previously it was poached for its skin but now it has found extensive application in Chinese medicine which includes various parts of its body. The animal is mostly found in the mangrove’s forests of Sunder ban region of India and Bangladesh [2] along with the Chittagong hill tracts as seen in (Figure 1).

The animal has been found migrating in Myanmar. A survey conducted in 2010 had estimated that this special population of Panthera Tigris Tigris is fewer than 1700 in the subcontinent [3]. Efforts are underway to save the species of Panthera by creating tiger reserves all over the country (but these will not be the Bengal tiger), as like every carnivore, tiger also sits delicately at the tip of the energy pyramid and at the end of the food chain. Any attempt to disturb this balancing act might ultimately result in extinction of the human population.

Behavioral pattern of the Bengal tiger

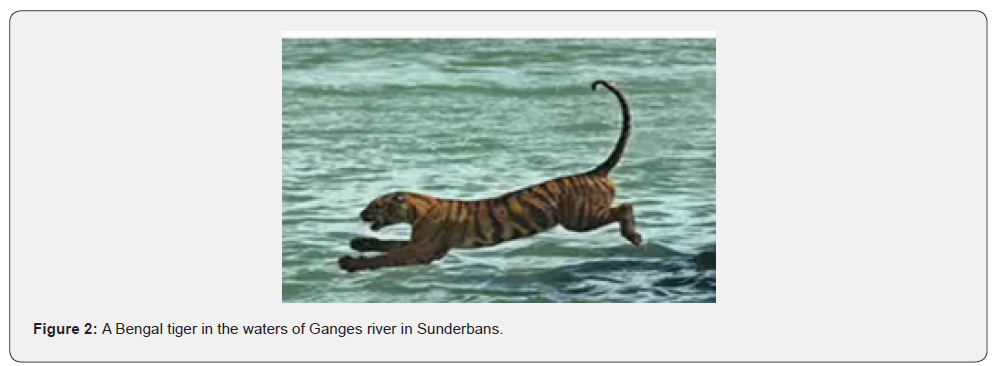

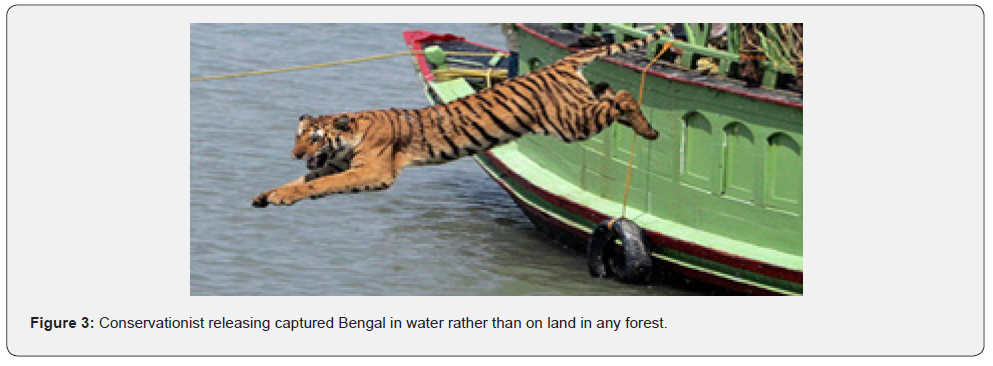

The animal lives a solitary life [4]. One might see on rare occasion that the female of the species moves with her cubs with the sole intention of either saving them from predators or teaching them how to hunt and if the cubs are too small, then feed them after she has made a kill. This is quite unlike the feline like the lion which has got very strict social order and they are always in groups. However, this is very similar to another carnivore, Asiatic cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus venaticus). This is main reason why these animals fall an easy prey especially to poachers. One of the other unique behaviors of Bengal tigers is that they are great swimmers of freshwater rivers like the river Ganges and its tributaries as seen in (Figure 2) in the delta region [5]. Conservationist will release captured animal in the water which is unlike the ones done in forest reserves where the animal is released in forest land as seen in (Figure 3).

Even they can jump from the shores on to fishing boats (mostly to pick up the fisherman as their prey) as shown in (Figure 4).Such types of activities are rarely seen in tigers which are found in forest reserves. Here the animal prefers to run and ambush the prey.

Feeding habits of Bengal Tiger

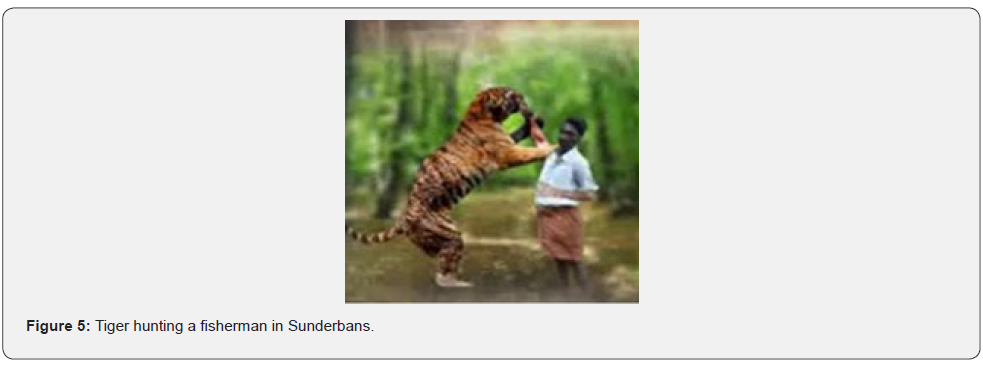

Unlike their cousins living in forest reserves, these animals do not feed on any animals howsoever large or small may it be. Since these are found in mangroves, it prefers to have fresh fishes (usually large carps, also called as Gangetic carps) like Catla catla, Cirrhinus cirrhosus, Labeo rohita etc [6]. which comes in the mangroves forest for breeding purposes. These fishes are found in the river water during early monsoon season when the tigers too have their feast. The animal often simply jumps into the river and catch the fully grown fish with the help of their mouth as seen in (Figure 5). Another unique character of these animals is that though they are in the delta region, they will never stray in the marine water to find food there. This is very similar to Grizzly bears or Brown bears (Ursus arctos) catching salmon (Oncorhynchus spp.) in the Brooks falls in Alaska, during the breeding season of the fish [7]. The only difference is that the bears rarely enters the cold water and prefer to catch the fish near the shore.

Later on as the monsoon picks up, the fish population reduces in rapid running water and at that time the animals move between the mangrove trees to find some adult fish still alive and trying to find a breeding ground. Later during the lean season when it is difficult to find fish, then these animals, move from the water to land (which are usually villages) to find preys like goat, cattle or their calves, and some animals like rabbit, deer, dogs, etc. Rarely they attack humans, unless provoked or are very hungry.

Now days there are alternate meadows with short grass and foraging animals like deer are being kept as prey for the survival of tigers as the mangroves are getting depleted fast due to human activities. However, since these animals are fond of the river, they are still trying to survive by feeding on alternate preys like fishermen from their boats as seen in (Figure 5).

Conclusion

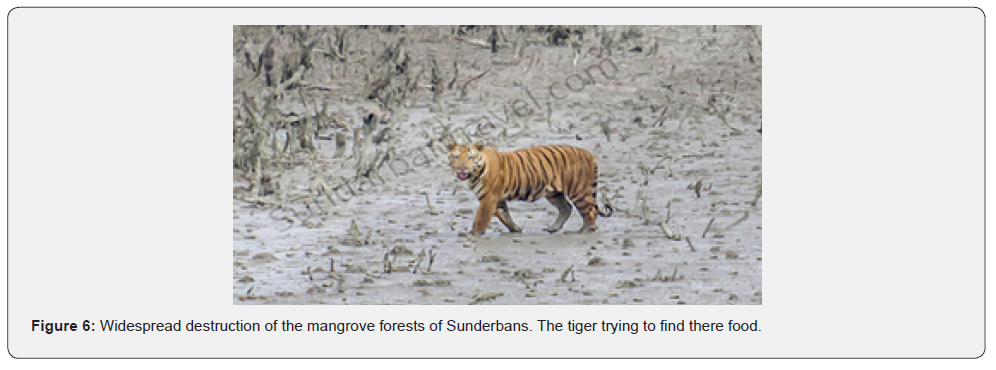

It is sad but true that this majestic carnivore, which once ruled mangrove forest like Sundarbans (which shows widespread destruction as seen in Figure 6) have now to find alternate homes like forest reserves with altered behavioral pattern for existence. The effect of such shifts has resulted in poor breeding of these animals. Time has come now to realize that mangroves should be restored (a very difficult process) and the corridors for such wildlife be returned. Next time one visits India to look for tigers in the forest reserves, one would definitely see them, but these will not be the Bengal tigers or rather Royal Bengal Tigers. In order to watch these royal creatures, one must take the boat ride through the Sundarbans mangroves only.

References

- Kitchener AC, Breitenmoser Würsten C, Eizirik E, Gentry A, Werdelin L, et al. (2017) A revised taxonomy of the Felidae: The final report of the Cat Classification Task Force of the IUCN Cat Specialist Group.

- Khan MMH (2004) Ecology and conservation of the Bengal tiger in the Sundarbans Mangrove forest of Bangladesh (PhD thesis) Cambridge: The University of Cambridge.

- Jhala YV, Qureshi Q, Sinha PR (2011) Status of tigers, co-predators, and prey in India, 2010. New Delhi, Dehradun: National Tiger Conservation Authority Govt. of India, and Wildlife Institute of India pp. 151.

- McDougal C (1977) The Face of the Tiger. London: Rivington Books and André Deutsch.

- Wikramanayake ED, Dinerstein E, Robinson JG, Karanth KU, Rabinowitz A, et al. (1999) "Where can tigers live in the future? A framework for identifying high-priority areas for the conservation of tigers in the wild". In Seidensticker J, Christie S, Jackson P (In Eds.). Riding the Tiger: Tiger Conservation in Human-Dominated Landscapes. Cambridge University Press. pp. 255-272.

- Sunquist M, Sunquist F, (2002) "Tiger Panthera tigris (Linnaeus, 1758)". Wild Cats of the World. University of Chicago Press. pp. 343-372.

- Hilderbrand GV, Jenkins SG, Schwartz CC, Hanley TA, Robbins CT (1999) Effect of seasonal differences in dietary meat intake on changes in body mass and composition in wild and captive brown bears. Can J Zool 1630: 1623-1630.