How much digitalization is worth for protected areas? Introducing “educational carrying capacity” after the Covid-19

Federico Niccolinia* and Fabio Fraticellib

Department of Economics and Management, University of Pisa, via C. Ridolfi 10, Pisa, Italy

Polytechnic University of Marche, Piazzale R. Martelli 8, Italy

Submission: June 06, 2020; Published: July 16, 2020

*Corresponding author: Federico Niccolinia, Department of Economics and Management, University of Pisa, via C. Ridolfi 10, 56124 Pisa, Italy

How to cite this article: Federico N, Fabio F. How much digitalization is worth for protected areas? Introducing “educational carrying capacity” after the Covid-19. JOJ Wildl Biodivers. 2020: 2(4): 555594 10.19080/JOJWB.2020.02.555594

Introduction

Specially among the US, in the past fifteen years it has been raising a scientific dialogue among educators, health professionals, parents, developers and conservationists. They are all concerned about the effects of the substitution of a physical world (outdoor activities, interaction with nature and “manipulation” of objects) with a virtual one (indoor activities and mass digital technologies usage). This shifting has been significantly accelerated due to the increase of digital activities occurred with the actual pandemic situation.

More than focusing on these effects, this study makes an attempt in defining a framework for the application of the “type” and “quantity” of information technology (intended here as IT and digital artefacts) that can be used in a protected area visit, as defined by IUCN (2008: 8). We want to propose a new and alternative perspective for the definition of how much of the recreational experience can be supported by the usage of information technology, without compromising the value recognition and the educational experience among visitors.

By lacking an established discussion on the topic, our study will proceed by analogy, defining the amount and type of technology usage as “crowding of information technology” and framing it with other types of “crowding’s” already studied within the management of outdoor recreation areas.

Under this point of view, our paper attempts to make an innovative use of the “crowding” concept to explain how electronics impact the relationship with natural environment and particularly to wildlife. We point out that increasing the available information technology (crowding of IT) leads a shift from a “real” approach to nature and wildlife to a “digital” or “artificial” one, since it is mediated by the same IT, namely a non-original element of wildlife experience.

Literary background

Crowding is both a research and a management-related issue for the outdoor recreation. Increasing visitor use and related impacts on recreation sites highlight the need for management tools that are suitable to solve the trade-off between visitor’s satisfaction and nature protection [1]. The past twenty-five years reported several contributes aimed to propose methods to measure the experience felt by people and to define the recreational carrying capacity of places [2,3]. All these contributions conceive carrying capacity as the amount and type of visitor use that can be accommodated appropriately within a protected area, especially for recreational purposes. Carrying capacity takes into consideration the quality of visitor experience (social carrying capacity) and its impact on resource conditions (resource carrying capacity); National Park Service, 1997; [4-6]. Traditionally, “visitor experience” refers to the continuum of options among solitude or access to a recreation area, while “resource conditions” refer to deterioration in several parameters that define the preservation of a recreation area.

Study Object

With this paper, our aim is to introduce the idea of usability of the concept of carrying capacity, by referring to the amount and type of digital technology that can be used appropriately within a protected area. While considering that the scope of our “digital carrying capacity” moves from the sphere of physical environment to that of psyche and human behavior, we could partially borrow some of the main concepts of the social carrying capacity: “solitude” and “access” will be switched into “connection” and “disconnection”.

Our key question is “could we refer to organization’s mission in order to assess the amount and type of digital technology that can be used appropriately within a protected area?”

The mission answers to the question “Why does the organization exist?”. According to some authors [7]. the answer is the essential scope (core purpose) of the organization. It is the “raison d’être”, not only an objective or a strategy. According to the IUCN (2008), the mission of a protected area is wide and can be fundamentally declined in 4 typologies of core scopes: conservation (of ecosystems and wildlife), research, education (to nature conservation) and (compatible) recreation.

Our proposal is to link the concept of carrying capacity to the protected area mission and scopes, identifying an alternative classification of carrying capacity in these 3 categories:

1. “Conservation Carrying Capacity”, that refers to the impact on resource conditions, corresponding to the traditional “Natural Carrying Capacity”

2. “Recreational Carrying Capacity”, that takes into consideration the quality of the visitor experience and corresponds to the traditional “Social Carrying Capacity

3. We also propose a completely new typology of carrying capacity that is “Educational Carrying Capacity”, based on the coherence of the activity done in a protected area with the PA’s educational mission of “build a citizenship committed to preserve its heritage and its home on the hearth” (US Department of Interior - National Park Service Advisory Board, 2001).

4. We suggest to PAs managers to introduce and refer to the third kind of carrying capacity to assess the amount and type of technology that could be introduced in protected areas visiting experience.

A pioneer case study

Some pioneers protected areas have already launched programs to evaluate the effect of IT introduction on educational experience. It is the case of Acadia National Park, an historical (established in 1916) protected area located along the coast of central Maine (USA). More than 2,300,000 people come to Acadia from all over the United States and numerous foreign countries each year. In 2011, Acadia National Park management, partnering with local Friends Group (Friends of Acadia), created a team and started a program “Youth Tech Team (YTT) summer program” to suggest ways the park use technology to engage youth and improve the visitor experience without decreasing the educational one. The YTT proposed a set of 23 different projects. This team applied methods of recreational carrying capacity to generate a portfolio of tech ideas (prototypes) suitable to be introduced within the Park with the aim to facilitate, not replace or discourage, experiences with trails, plants, artefacts, animals and people of the park. The Acadia YTT prototyped and evaluated different areas of digitalization of visitor experience such as IT mediated experiences (e.g. Digital Birds Watching, live or recorded depending by weather conditions), mobile Apps (e.g. Plants Identification with an App). The YTT experience functioned as dialectic space [8] to compare the perspectives of members enthusiasts for the introduction of new technologies, and other that were worried about their “disconnection potential”. This debate brought to the solution to integrate the evaluation traditional recreational outcomes (visitor satisfaction ….), with the educational mission-related dimensions of “connecting people to the park” every time a new IT action is introduced. The YTT scored each of the YTT tech ideas by referring not only to traditional parameters as its financial sustainability, but also to educational ones, such as the connection to NPS general strategic goals (themes). Every IT ideas have been so assessed through the connection with NPS mission (including the educational one).

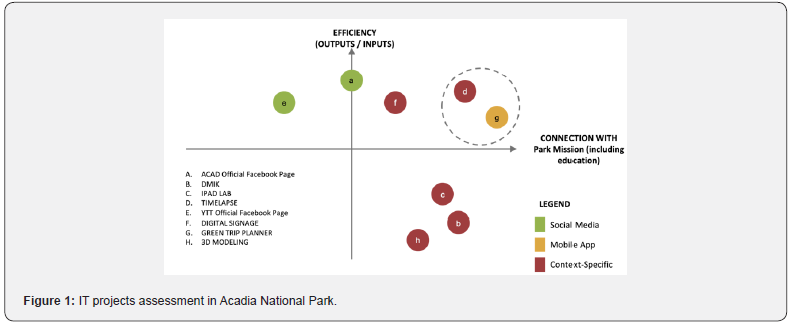

The YTT adapted and used already existing theoretical frameworks, such as the indifference curve analysis [9]or the methodological approach of paired comparisons [10,11], to make evaluations on how much the real educational experience could have been affected by the digitalization of the same. Operatively, the YTT built a set of questions aimed to evaluate how many educational missions were accomplished by each tech idea (using a Likert scale, 1-5). Questions as “Through this project, to which extent will you involve youth in creating new expressions of the park experience with fresh perspectives and new technology?” have been administered before introducing a project [12-14]. This way tech projects have been assessed in a comprehensive manner, namely considering both financial, recreational and educationrelated aspects. For every tech project an evaluation positioning has been produced as shown in the following (Figure 1).

Conclusion

We propose to introduce a new category of Carrying capacity, the “Digital Carrying Capacity” (DCC), as a kind of “Educational Carrying Capacity” - that considers the possible degree of “reduction” of the human-nature connection due to the introduction of new IT visiting experience in a protected area. Our proposal shows that the Digital Carrying Capacity can be expressed in terms of degree of coherence and impact on the PAs educational mission. An IT project with a high level of DCC suggests that it contributes to the organization’s mission achievement without compromising the educational experience. Particularly after the tremendous shift to digital behaviors accelerated by the digitalization of educational/teaching experience for younger generations during the Covid-19 lockdown, it is essential (and would be much more in the future) that PAs decision makers will evaluate educational trade-offs in IT usage for outdoor recreation as for other primary goals of protected management.

References

- Hallo JC, RE Manning (2009) Transportation and recreation: A case study of visitors driving for pleasure at Acadia National Park. Journal of Transport Geography 17(6): 491-499.

- Clark JR, (1996) Coastal Zone Management Handbook, 1st (Edtn) CRC Press, Florida.

- Manning RE (1999) Studies in Outdoor Recreation. Oregon. 2nd edition Oregon State University Press.

- Graefe AR, JJ Vaske, Kuss FR (1984) Social carrying capacity: An integration and synthesis of twenty years of research. Leisure Sciences 6(4): 395-431.

- International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), (2008) World Commission on Protected Areas (WCPA), Guidelines for Applying Protected Area Management Categories, Gland, Switzerland.

- Lawson SR, Manning RE (2001) Solitude versus access: A study of tradeoffs in outdoor recreation using indifference curve analysis. Leisure Sciences 23(3): 179-191.

- Collins JC, Porras JI (1996) Building your company's vision, Harvard business review 74(5): 65.

- Nonaka I, Konno N (1998) The concept of “Ba”: building a foundation for knowledge creation”, California Management Review 40(3): 1-52.

- Nicholson W (1995) Microeconomic theory: Basic principles and extensions (6th edtn.) Fort Worth: The Dryden Press.

- Louviere JJ, G Woodworth (1985) Models of park choice derived from experimental and observational data: A case study in Johnston County, Iowa. University of Iowa Technical Report, Iowa City, Iowa.

- Louviere J, Timmermans H (1990) Using hierarchical information integration to model consumer responses to possible planning actions: Recreation destination choice illustration. Environment and Planning, 22(3): 291-308.

- Lime DW, Anderson DH, Thompson JL (2004) Identifying and Monitoring Indicators of Visitor Experience and Resource Quality: A Handbook for Recreation Resource Managers. St. Paul, MN: University of Minnesota, USA.

- Louv R (2008) Last child in the woods: Saving our children from nature-deficit disorder. Algonquin Books.

- US Department of Interior - National Park Service Advisory Board (2001) Rethinking National Parks for the 21st Century Ed. National Geographic, Washington DC, USA.