The Behaviors of Himalayan Marmot (Marmota Himalayana) in the Alpine Mountains of Jigme Dorji National Park

Jangchuk Gyeltshen*

Department of Forest and Park Services, Phrumsengla National Park, Royal Government of Bhutan

Submission: February 26, 2020; Published: March 10, 2020

*Corresponding author: Jangchuk Gyeltshen, Department of Forest and Park Services, Phrumsengla National Park, Royal Government of Bhutan

How to cite this article: Jangchuk Gyeltshen. The Behaviors of Himalayan Marmot (Marmota Himalayana) in the Alpine Mountains of Jigme Dorji National Park. JOJ Wildl Biodivers. 2020: 2(2): 555586 DOI: 10.19080/JOJWB.2020.02.555586

Abstract

Visual observation method was used to conduct study on the behavior of Himalayan Marmot (Marmota Himalayana Hodgson, 1841) from May 2000 to October 2005 in Jigme Dorji National Park (JDNP) in three different sites. The main objective of this study was to document the behavior of Himalayan Marmot and address its emerging anthropogenic threats for survival in the alpine mountain ecosystem. Foraging habits, vigilance during foraging, tune of calls, tail flicking, parental care, standing upright posture, response to predators, plant collection and storage, play fight, hearing power and sensation of vibration, hibernation and arousal were the behaviors documented during the study. The collection of Chinese caterpillars (Ophiocordyceps sinensis), increasing number of livestock and feral dogs were the immediate emerging threat to the survival of Himalayan Marmot in its natural habitats.

Keywords:Himalayan marmot; Behavior; Threats; Jigme Dorji National Park

Abbreviations: JDNP: Jigme Dorji National Park; BWS: Bumdeling Wildlife Sanctuary; JKNWSR: Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck Strict Reserve; FID: Flight Initiation Distance

Introduction

Himalayan marmot (Marmota himalayana Hodgson, 1841) are found across portions of Asia, Europe, and North America and they are restricted to the northern hemisphere of our earth [1]. Himalayan marmots are considered one of the highest elevations living mammals in the world [1]. They are about the size of a large housecat and live in colonies. It has a dark chocolate-brown coat with contrasting yellow patches on its face and chest. The average animal weighs more than 7kg. Today, there are 15 species of Marmots recognized in the world [2]. Himalayan marmot is classified as Least Concerned under IUCN Red List of Threatened Species [3]. They belong to order Rodentia and family Sciuridae. Only two species of marmots occur in India, viz., Long-tailed marmot Marmota caudate and Himalayan marmot Marmota himalayana [4].

In Bhutan, only one species of marmot is recorded, viz., Himalayan marmot (Marmota himalayana). Out of ten protected areas in Bhutan, Himalayan marmot can be seen only in three protected areas. These are Jigme Dorji National Park (JDNP), Bumdeling Wildlife Sanctuary (BWS) and Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck Strict Reserve (JKNWSR). In JDNP, this animal is found in the alpine meadows between the elevational ranges of 3600m-4594m. However, in Le Ladkh, Jammu and Kashmir, the animal is seen within 4000m-4500m [4]. Owing to its habitat suitability, JDNP have the highest number of population than other protected areas. However, there is lack of baseline information and documentation on the behaviors. The study of behavior is important in providing early warning signs of environmental degradation and understanding the differences in adaptability between species that can live in a variety of habitats versus those that are restricted to limited habitats which can lead to understanding of how we might improve human adaptability as our environment change [5]. Therefore, the aim of this study was to document behaviors and understands how this animal is coping up with the changing environment in its natural habitat in the alpine mountains of JDNP.

Materials and Methods

The study on the behavior of Himalayan marmot was conducted in three study sites under JDNP from May 2000 to October 2005 (Figures 1 & 2). These sites are Gyalpoteng under Soe Park Range jurisdiction (N 27°46´59.76”N, E 089°21´05.30”, Alt-4300m), Dingthang under Lingshi Park Range jurisdiction (N 27°43´26.21”N, 89°32´39.27”E, Alt-4350m) and Langothang under Gasa Park Range jurisdiction (N 28°04´01.78”N, 89°41´46.33”E, Alt-3914m). Jigme Dorji National Park is the second largest protected areas in Bhutan with area coverage of 4316km2. The park is situated in the northwestern part of Bhutan with altitudinal gradient ranges from as low as 1500m to permanently snow-clad mountains that are over 6500m [6]. The huge variation of altitudinal gradient supports a diverse array of flora and fauna. Currently, the park habors more than 100 species of mammals, 317 species of birds and some of the charismatic species of the mammals like Snow Leopard, Tiger, Clouded Leopard and Red Panda [6]. Visual observation method was used to study and document the behavior of Himalayan marmot. A vantage point was selected near its habitat and used for observing the behavior. Hill tops, big boulders and tall herbaceous plants were also used to conceal from the animal. The observations were made in the morning before sunrise and after sun set. Avoided observation during cloudy and foggy days. A binocular (Nikon) was used to observe behavior from the far of places without disturbing the animals. Sometimes the marmots were disturbed to study its responsive behaviors. Digital Camera (Sony Snapshot, Mega pixel 14), GPS (Garmin), Altimer (Suunto) and diameter tape were used during the study.

Results

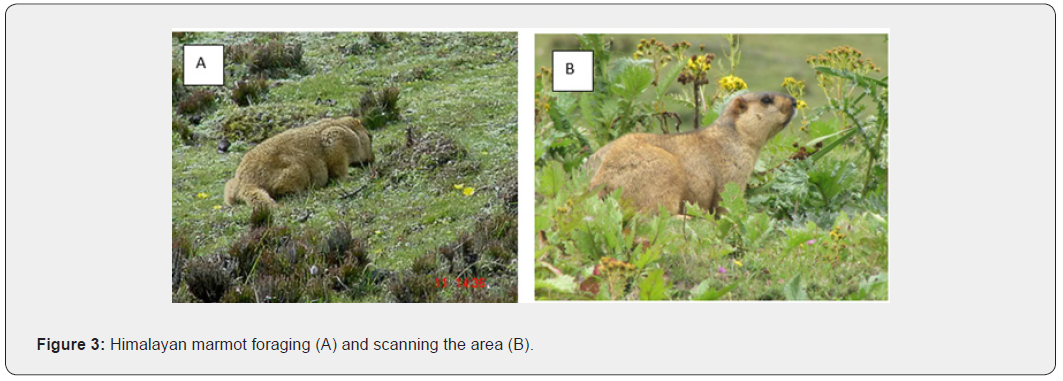

Foraging habits

It was observed that for short grasses and herbs, Himalayan Marmot foraged like an ungulate and for tall grasses and herbs they fed like monkey using its forepaw (Figure 3). They preferred to feed on new shoots and leaves of the edible plants leaving marks of incisors. As observed by Armitage [2], they were also found feeding on flowering plants because it is palatable and contains higher amount of proteins, fatty acids and minerals good for when they go under hibernation. Feeding activities were recorded highest in the morning during clear sunny day and lowest in the late evening before sunset. This was the time where livestock (Yaks & horses) were kept near the herders’ tent and no heavy disturbances in the habitats. Marmots were seen foraging very less during rainy and foggy day. This could be attributed to avoid predators due to poor visibility. Often, marmots are also seen foraging on the same ground together with livestock when there were no human disturbances. This was even reported by Ulak & Nikol’skii, that where there is the livestock bite of apical shoots, which helps to increase in the Phyto mass of young plants favored by the marmots [1].

Vigilance during foraging

It was observed that the Himalayan marmot remained alert during foraging and become extra vigilance in scanning the area when the group had young pubs (Figure 4). This was even reported by Blumstein and Daniel during their experiment on Yellow-bellied marmots [7]. They also remained vigilance when they foraged in thick and tall grasses or herbaceous plants. This may be the strategy to avoid confrontation of predators. The vigilance is said to be influenced by microhabitat characteristics and prey and the animal becomes less vigilance when peripheral visibility is better [8,9]. It was observed that marmot was found more vigilance during foraging in the high pastoralism sites than in low pastoralism sites.

Tune of calls

Two types of calls were noted in the field. One with long interval and of low pitch call which signaled that he/she is trying to find friend or partner. One with very short interval and of high pitch call signaled which is to avert/warn danger to the members. The members can easily make note of those calls when they feed on the ground. The call of Himalayan Marmot resembles those of Altai Marmot and Woodchuck.

Tail flicking

It was observed that the marmot flicked its tail whenever they moved their body, while feeding and while reaching at the entrance of their burrows. They also usually flicked their tail before escaping into the burrows. The literature stated that flicking of tail indicates the level of excitement or alertness.

Parental care

It was observed that during the month of May to July, the young pups of Himalayan marmot often came out from the burrow when their mothers were feeding on the ground but mother pushed back her pups with her nose into the burrows when she saw danger of attacking outside its burrows. Mother left her pups feed on the ground when there was no danger around then, but she remained alert all the time while feeding. Lammergeier (Gypaetus barbatus) was suspected to be preying on Himalayan Marmot pups, because we have observed that mother get agitated and made warning call when Lammergeier was found flying overhead and hovering around their habitats. They warned and alerted others by emitting sharp whistle chuk-chuk-chuk-chuk. It was found out that there is different frequency of calls made by the female to warn their individual pubs [7]. Golden eagle is also expected to be preying on marmot. However, such incidences are not observed in our park.

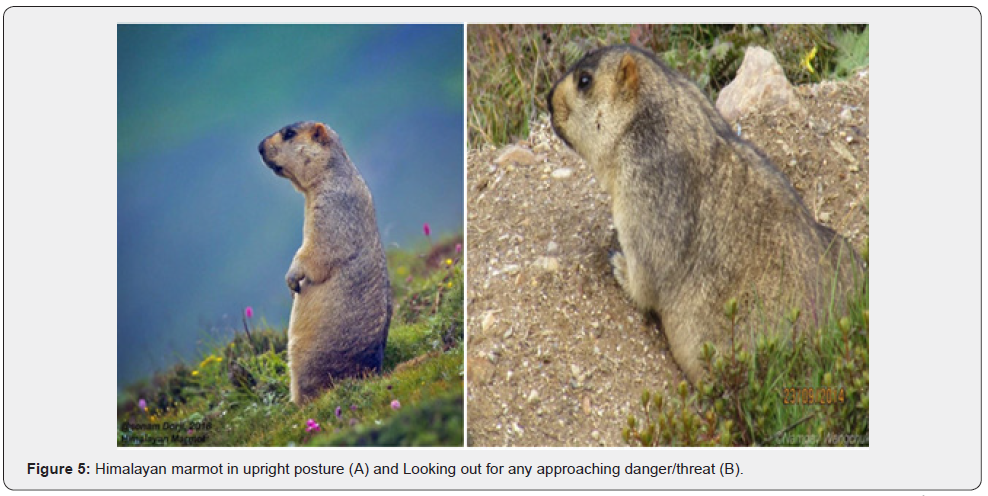

Standing upright posture

This behavior was normally observed when Himalayan marmot sensed disturbances or approaching of predator within their habitats (Figure 5). It was observed that they remained upright posture for 2-5minutes and warned other members of approaching predators through their calls. This type of habits was mostly noticed especially when they were feeding in tall grasses and herbaceous plants to scan the danger around them. Standing upright posture was also observed during mating season and to look out for danger near their burrows. Local resident in its habitat said that when this animal is being chased and try to attack by dogs, this animal folds its hand and show their breast to convey message that she has young pubs to feed. Yet, we haven’t sighted this situation.

Response to predator

The Himalayan marmot was observed as one of the fastest animals to react to the approaching predators. It was observed that they have one or more member in their colonies to look after the group. Two different types of pitch of alarm calls were recorded in the field; a whistle with low pitch was blown when predator was approaching from far distance and a sharp fast whistle with high pitch was blown when the predator was approaching within proximity. It is also noted this behavior in Yellow-bellied marmot and in Whistling rats [10]. When whistle is blown, the group member runs toward their own burrows and remained in upright posture to judge the proximity of danger. They directly escaped into their burrows when they encountered direct threat to their life. Bonefant & Kramer studied the Flight Initiation Distance (FID) of Woodchuck Marmota monax and proved that anti-predator behavior is sensitive to the costs and benefits of alternative escape decisions [11]. The study showed that there was highly significant positive relationship between FID and distance to burrow for both the slow and fast approaching predators. Nikolskii suggests that natural selection has fixed call patterns that are optimal for the local landscape [1]. Calls may also be directed to the predator and may function to discourage pursuit, or perhaps to attract other predators which would create competition, or predation on one predator by another, thus allowing the prey to escape [10]. Furthermore, Blumstein reported that Caller reliability can be evaluated in two ways: receivers could either assess characteristics of reliable and unreliable classes of callers, or they could discriminate among individuals. Marmots generally emit one single alarm responding to an aerial stimulus, and multiple alarms in response to terrestrial threat [12]. However, this needs to be studied for the Himalayan Marmot as well (Figure 6).

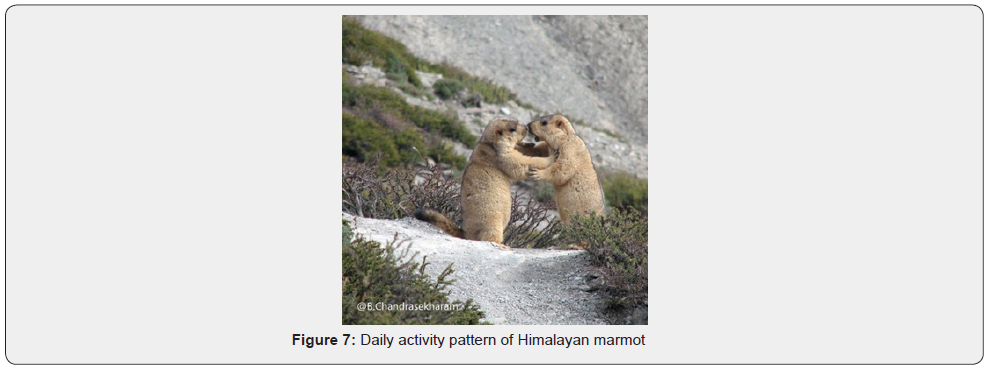

Play fight

The Himalayan marmots were observed boxing each other at the entrance and nearby burrows. Both the fighter used forepaws to push forwards. During boxing, they pushed and kissed each other (Figure 7) and ran few distances from the burrow entrance and again came to burrow entrance [13]. They often roll and wage their tails which was as a sign of not fighting it but rather mean they are playing [14]. It’s said that this kind of fight is not be considered aggressive instead it’s a ritualized form of play to distinguished between foe and friend among the groups. It was observed that they made noise and ran few meters from their burrows and halted and fought again and again. This activity continued for sometimes. Blumstein [1992] reported that such fight among adult and young pubs may be a practice to get adapted when confronted with the actual predators [14] (Figure 8).

Plant collection & storage

It was observed that few Himalayan marmots especially the adult Marmots were found collecting and feeding grasses during the onset of hibernation. They were found collecting palatable grasses for feeding before one month of hibernation and nonpalatable grasses and herbaceous plants like Aconitum sp. and Rhumax nepalensis and torn out clothes to be used as bedding in the burrows. The collection activity was found decreasing as the month passed by. The evidence suggested that the marmots may be feeding even during the hibernation period but available literature says that they only depend on fat stored in their bodies.

Hibernation & arousal

Before hibernation, Himalayan marmots were found preparing beddings. They were found digging burrows and throwing out old soil and bedding materials outside the burrows. They collected twigs of shrubs, herbaceous plants and thrown out old cloths. They also changed their bedding inside its deep burrows. Unusable twigs, grasses, cloths and dug soils were found thrown out and kept piling near its burrow openings. It was observed that Himalayan Marmot did not hibernate at once. The populations were found gradually decreasing from mid-September to end of October. No marmots were seen above the ground after October. They went under hibernation for six months viz. November, December, January, February and March, April. In those months the alpine meadows frequently experience snowfall and remains under harsh climatic condition. They emerged from the burrows in early May. Most of the young pubs with her mothers and sub-adults were observed as first to emerge from its hibernation and matured adults were the last to hibernate.

Hearing power & Sensation of vibration

It was observed that the Himalayan marmot had good sense of hearing and vibrations when they were found forage on the ground and when they were inside the burrows. This was field tested by walking above the network tunnel of their burrows once marmot escaped into the burrows. In many locations, we walked over the burrows and waited marmot to come out from the burrows but did not turned up. Once we were away from the network of tunnel of burrows for a longer period, we observed marmot showed their heads and looked out for danger. This confirms that they have good sense of feeling vibration on their body to detect predators. The stray dogs and other wild predators often take advantages of this sensation whereby they remain complete silence, hide and wait without movement for long duration near burrow entrance. They attack marmot when comes out from the burrows. Some researchers have explored how rodents react to the different seismic communications conveyed by the prey and predators [7]. However, little is known on this regard for the Himalayan Marmot in Bhutan.

Wrong attempt to enter into other burrows

It was observed that the feeding takes place within a maximum radial distance of 30meters from the center of their burrows. Beyond, which, the animal is more liable to fall victims to the predators because of loss of memories to trace back their burrows. This was field tested by chasing the animal wherein the animal happened to run in wrong direction and missed their burrows. Some they ran and escaped into other burrows but soon heard sound of aggression and fighting inside burrows. After we left burrows, they came out and ran to their own burrows. This confirmed that the animal have their own burrows to live in. It was observed that the maximum distance travelled by the Himalayan marmot from their burrow is 48meters [13], whereas in this study it showed radial distance of 30m from its burrow.

Discussion and Conclusion

The Himalayan marmot is one of the least-understood marmot species whose ecology is poorly known [13]. Several authors had confirmed Himalayan marmot (Marmota himalayana) as the main prey species for snow leopard [15]. However, no detail study has been conducted to point out Himalayan marmots as a prey species for Snow leopard in Bhutan. Forget this, even the behavioral ecology of this animal is not yet documented. Besides playing vital ecological role in the alpine mountainous ecosystem of the park, this animal also has strong religious reverence by the local community. The local community call marmot as ‘Gomchen Chewoo’ which means “great meditator”. They said that this animal could meditate underground for long periods in a year. Local community consider killing of marmot as severe sinful act. They believed that the sin of killing a marmot is equivalent to killing one great meditators. As of now, there was no single report on killing or hunting by the local communities. No report on the damages of properties as well even though they were found living very close to each other. Unfortunately, the animal is under constant anthropogenic threats in its habitats. Collection of Chinese caterpillar (Ophiocordyceps sinensis) and increasing number of livestock and feral dogs in its habitat are some of the emerging threats besides climate change impact. Therefore, in the long run, it is likely to influence behaviors and population as well. Time of foraging is also likely to reduce thereby resulting to loss of body mass to store enough fats for the winter season, which is in line with what Mathews et al. [9] had reported [9]. The body mass gained during growing season of marmot is not just for winter survival, but for subsequent reproduction in marmots [13]. Already one can observed abandoned burrows in different habitats, which indicates that the population of the marmot is declining. Moreover, there was no record on the distribution range of this animal in Bhutan on the IUCN Red List [3]. Even in Nepal, Aryal et al. [16] reported that out of 82 interviewees, 69 of them had agreed that the population has declined over the past 10 years [16]. Therefore, immediate study is needed to understand the distribution, population status and threats of Himalayan marmot in the park before it is exposed to high risk of extinction.

Acknowledgement

I am thankful to Dr.Sangay Wangchuk (Late), the former Head of Nature Conservation Division and Mr.Tashi Wangchuk, the former Park Manager of JDNP, Department of Forests and Park Services for their encouragement and support to embark study on Himalayan Marmot since 2000 onwards. Both of them and other forestry colleagues in those days called me “Marmot” as my nickname which I was inspired to work on. Therefore, I would like to extend my deep gratitude to all of them.

I would like to acknowledge Dr.Blumstein, Blumstein Lab, California for reviewing my manuscript. I thanked Mr.Lhaba, then the Dy.Park Range Officer, Mr.Norbu and late Mr.Gyem Dorji, then the staff of Soe Park Range Office, JDNP who have spared their time with me laying on a cold grassy ground and patiently waiting to observe the behavior of Himalayan marmots. Their cooperation and support will never be forgotten in my life.

I am grateful to Mr.Namagy Wangchuk (NCD), Mr.Pema Kuenzang (JDNP) and Mr.Sonam Dorji for allowing me to use their photos of Himalayan Marmots. Without their support, I would have not come up with this paper.

References

- Ulak A, Nikolskii AA (2006) Key Factors Determining the Ecological Niche of the Himalayan Marmot, Marmota Himalayan Hodgson (1841). Russian Journal of Ecology 37(1): 46-52.

- Armitage KB (2013) Climate change and the conservation of marmots. Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, The University of Kansas, Lawrence, USA 5(5): 36-43.

- IUCN, Red List of Threatened Species (2016)

- Chaudhary V, Tripathi, Singh S, Raghuvanshi MS (2017) Distribution and population of Himalayan Marmot Marmota Himalayan (Hodgson, 1841) (Mammalia: Rodentia: Sciuridae) in Leh-Ladakh, Jammu & Kashmir, India.

- Snowdon CT Significance of Animal Behavior Research. California State University, Northridge. Animal Behavior Society.

- Tharchen L (2013) Protected Areas and Biodiversity of Bhutan. Department of Forest and Park Services, Ministry of Agriculture and Forests, Royal Government of Bhutan P. 42.

- Blumstein DT (2004) The Evolution of Alarm Communication in Rodents: Structure, Function, and the Puzzle of Apparently Altruistic Calling p.317-334.

- Blumstein DT, Ozgull A, VY ovovich, DH Han Vuren, KB Armitage (2006) Effect of predation risk on the presence and persistence of Yellow-bellied Marmot (marmot flaviventris) colonies. Journal of Zoology 270(1): 132-138.

- Mathews A, Spooner PG, Poudel BS (2015) Temporal shift in activity patterns of Himalayan marmots in relation to pastoralism. Behavioral Ecology 26(5): 1345-1351.

- Blumstein DT (2004) The Evolution of Alarm Communication in Rodents: Structure, Function, and the Puzzle of Apparently Altruistic Calling p. 317-334.

- Bonenfant M, Kramer D (1996) The influence of distance to burrow on flight initiation distance in the woodchuck, Marmota monax. Behavior Ecology 7(3): 299-303.

- Ferrari, C (2010) Personality and vigilance behavior in alpine marmot. UNIVERSITÉ DU QUÉBEC À MONTRÉAL p. 70

- Poudel BS, Spooner PG, Mathews A (2015) Pastoralist disturbance effects on Himalayan marmot foraging and vigilance activity. Ecol Res 31(1): 93-104.

- Blumstein DT Boxing Marmots: Functions of play. Natura p.9.

- Oli M, I Taylor, M Rogers (1993) Diet of the snow leopard (Pantheva uncia) in the Annapurna Conservation Area, Nepal. Journal of Zoology 231(3): 365-370.

- Aryal A, Brunton D, Ji W, Rothman J, Coogan CP (2015) Habitat, diet, macronutrient, and fiber balance of Himalayan marmot (Marmota himalayana) in the Central Himalaya, Nepal. Journal of Mammalogy 96(2):308–316.