Biotechnological tools for quality olive growing

Maurizio Micheli1* and Daniel Fernandes da Silva2

1 Department of Agricultural, Food and Environmental Sciences, University of Perugia, Italy

2Universidade Estadual do Oeste do Paranà, Marechal Candido Rondon, Rua, Brazil

Submission: February 17, 2020; Published: February 27, 2020

*Corresponding author: Maurizio Micheli, Department of Agricultural, Food and Environmental Sciences, University of Perugia – Borgo XX Giugno 74, Perugia, Italy

How to cite this article: Maurizio Micheli, Daniel Fernandes da Silva. Biotechnological tools for quality olive growing. JOJ Wildl Biodivers. 2020: 2(1): 555583 DOI: 10.19080/JOJWB.2020.02.555583

Abstract

Although olive cultivation is practiced in the Mediterranean Basin for centuries and the current diffusion of oliviculture worldwide is largely plain to see, even today mass propagation of olive trees (Olea europaea L.) through the in vitro techniques finds impediments due to a series of problems. So, differently of other species, micropropagation of olive isn’t yet a commercial practice, even if it could represent a suitable solution to obtain high-quality and quite safe plant material. In this work strength points, problems, expectations and perspectives of micropropagation applied to olive are reported.

Keywords:(Olea europaea L.); Micropropagation; Conservation; Axillary buds; Bio stimulants

Introduction

Current problems of olive growing

Important changes in the olive cultivation sector are requested, where the enhancement of quality production, the economic and environmental sustainability of cultivation practices and the safeguarding of the typicality of local products still play a fundamental role. All of this could still be considered a priority if particularly relevant urgencies did not prevail, such as those which currently polarize the attention of farmers, technicians and researchers. In fact, relevant phytosanitary emergencies seem capable of influencing both current and future crop and/or production strategies in the olive sector. In this context, the certification of propagation material still appears to be the only effective approach to guarantee the production and spread of genetically uniform and safe plants free from major diseases.

New approaches are necessary in order to safeguard the quality of internal production, but also to support the competitiveness of our nurserymen on the globalized world market. During the last decade a strong request of olive plants was leaded by the expansion of this crop also in Countries not traditionally producing olive oil, outside the Mediterranean Basin.

In the face of this vision, current economic difficulties would seem to be the main causes of many deeply rooted problems. An example is the spread of particularly virulent pathogens, such as those contributing to the main emergency of the moment in Southern Italy, where olive trees are affected by extensive leaf scorch and dieback due to the bacterium Xylella fastidiosa. In this regard, the measures indicated by the phytosanitary services of the regions involved foresee a strong preventive action; it can be pursued both through the adoption of suitable and correct cultivation practices, and the use of high-quality propagation material, not only olive trees, but also all species susceptible to the parasites involved. However, at the moment the situation is really dramatic. A recent document produced by Italian local associations of fruit, viticulture and ornamental nurseries [1] refers to the numerous problems connected with the Xylella emergency, including those connected to the movement of propagation material inside the countries.

In this overall context, the contribution of all the parties involved is important. Among them, the role of research seems essential: although conditioned by the scarcity of resources, it has proven to be able to transfer new knowledges and informations to olive growers, useful for all stages of production.

A specific area concerns the propagation. The enhancement of the quality and quantity of production has to start from the possibility of produce plants through plant material characterized by genetic and sanitary quality. The currently most widespread techniques remain the traditional multiplication by cutting and grafting. The prevalence of one depends on many factors, including the genotype to be propagated, the production area, agronomic needs, traditions and the market. In any case, the nursery chain is focused on production of higher quality plants, which allow to prevent the spread of quarantine diseases, and on traceability implemented by the certification of the propagation material, regulated in Italy by the National Certification System.

Biotechnological support

In this perspective, a method of propagation “integrative” to the traditional ones can certainly be considered the micropropagation. It implies the concept of “aseptic culture of small portions of tissues or plant organs, on artificial nutrient substrates, inside containers and in controlled environment conditions”. Scheleidan and Schwann can be considered the fathers of in vitro cultures, when in 1838 developed the theory of plant cellular totipotency, together Haberlandt who identified the existence of growth hormones. In 1922 Robbins and Kotte, using mineral salts, yeast and sugar extracts as substrate, cultivated individual shoots and roots meristems; in the same year the first document relating to in vitro techniques for the vegetative propagation of plants was published by Knudson [2]. Finally, in 1962, Murashige & Skoog [3] identified a formulation of mineral salts, vitamins and hormones for the cultivation of tobacco explants; this substrate proved to be effective for many other species and is still widely used today. From the 60s of the last centuries, micropropagation was applied on a large scale, but it is during the last 30 years that, also in Italy, it has assumed an increasing interest in public and private laboratories operating especially in the nursery productions. For many years certain peculiarities of micropropagation seemed apparently an obstacle to its commercial diffusion: high costs of installation and skilled labor skilled labor; difficulty of propagating species recalcitrant to in vitro culture; prolonged juvenility period that some genotypes can manifest in the field; the need to frequently renew the propagation material, by taking samples from selected mother plants, in order to limit the possibility of onset of genetic variations. But, this technique offers a large number of advantages compared to the more traditional ones: rapid clonal multiplication for the production of rootstocks and genotypes characterized by being resistant to certain parasites, when it is difficult to find the base material; high genetic and phenotypic uniformity of plants; sanitary guarantee of the material propagated in asepsis, easy to transfer and to market in Countries where restrictive phytosanitary laws are in force; possibility of cloning plants difficult to propagate with traditional methods; containment of unit production costs for those species a consolidated micropropagation protocol is available; release of the phases from seasonal trends and planning of productions based on market demands; possibility of conservation or short period storage of propagation material; availability of new technologies to automate some phases and, therefore, contain production costs.

Commercial Micropropagation and Perspective for Olive Trees

In Italy around 2011 there were 24 commercial micropropagation laboratories with a production of almost 30 million high quality plants, represented by fruit trees and ornamental flowers, using all in vitro regeneration processes (stimulation of axillary buds, somatic embryogenesis and organogenesis). While the technique based on the stimulation of the axillary buds has been widely tested, the other two are not yet available for the clonal propagation of cultivars and rootstocks, both for the lack of certain protocols and for some important problems associated with regenerative procedures.

As regards the olive tree, the first experiences of micropropagation trace back to the ‘70s of 1900, but only after the first specific studies on the nutritional needs of this species [4], this technique entered among the clonal propagation systems applicable to the olive tree. However, compared to other species, micropropagation of olive does not yet have a prominent place in the commercial nursery business.

In fact, currently only 1% of the production of olive trees in Italy is obtained by applying in vitro propagation techniques [5], particularly from stimulation of axillary buds of uninodal explants, taken from selected mother plants. Under suitable nutritional and environmental conditions, the development of new shoots is induced (Figure 1) and, subsequently, of the root system, until the production of whole vitro-derived plantlets is achieved.

The application of micropropagation for olive is still limited. The reasons are mainly to be found in some specific causes: difficulty in standardizing the procedures due to a significant genotype-dependence; need of further studies on the field behavior of micro propagated plants compared to those obtained through more traditional methods; ineffectiveness of other regenerative processes, potentially more productive than multiplication by axillary buds, but still not safe from the point of view of genetic certification; high cost of zeatin, that is currently the most effective plant growth regulator to stimulate satisfactory levels of multiplication rate. In this regard, the in vitro growth of the olive occurs mostly by elongation of initial shoot stem. This behavior would seem associated with the strong apical dominance manifested both in vivo and in vitro culture conditions. In conclusion, zeatin still represents the most effective hormonal component to stimulate a satisfactory level of proliferation for most of the propagated cultivars, according to a large amount of scientific evidence [6].

Research and results in the field of olive micro-propagation seem to be a step backwards compared to other species (especially fruits and ornamental plants). However, the current conditions facing the olive sector should stimulate professionals and nursery operators to open up new perspectives, trying to integrate traditional methods of production with new techniques and technologies, capable of contributing to overcoming those critical issues that, at the moment, seem to strongly influence the whole chain.

There are spaces, even in the sector of quality propagation: courageous choices must be made and those engaged in experimentation must be supported. In the face of very few resources, many researchers are studying to propose suitable solutions to overcome the problems that still limit the application of in vitro culture even in olive.

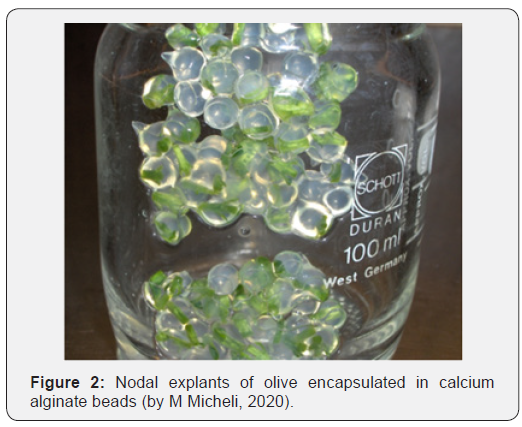

The main objective is the improvement of productivity of micropropagation in all its phases, studying: the use of growth regulators alternative to zeatin; the effectiveness of nutritive substrates more responsive to the trophic needs of each cultivar; the evaluation of natural compounds (biostimulants) able to improve the effect of nutritive media; the adoption of innovative culture systems on liquid or semi-liquid soils (temporary immersion); the effect components of substrates able to provide suitable energy sources to the explants (carbohydrates); the effectiveness of new procedures to induce rhizogenesis in in vitro or in vivo conditions, in order to reduce the transplant stress and the acclimatization period, accelerating the return to the autotrophic state of the vitro-derived material; the suitability of innovative protocols resorting to the use of microorganisms (fungi and/or bacteria) to stimulate the vegetative vigor of the young plantlets (biotization); the use of alternative light sources both in aseptic conditions and in ex vitro environment; the adoption of technologies, such as encapsulation in calcium alginate (Figure 2) the aim to simplify the management and diffusion of plant germplasm by using beads and/or synthetic seeds) [7-9].

Many researches require multidisciplinary skills and also an important economic support, currently quite limited if resulting from dedicated public funds. Private individuals (olive growers and all those involved in related activities) are asking for a strong commitment, an important effort to pursue common objectives and seek points of convergence with the research sector (public and private). This, represented in 2011 by about 40 laboratories dedicated to tissue culture experimentations, should deal more with the subjects involved in the production, making available their skills in research to more applicative objectives, responding to the current needs of the sector, increasingly oriented towards innovation and the search for effective technological solutions.

References

- ANVE, Associazione Vivaisti Viticoli, Civi-Italia, MIVA (2015) Posizione e contributo del comparto vivaistico italiano sull’emergenza Xylella fastidiosa.

- Knudson L (1922) Nonsymbiotic germination of orchid seed. Botanical Gazette 73(1): 1-25.

- Murashige T, Skoog F (1962) A decisive medium for rapid growth and bioassays with tobacco tissue culture. Physiol Plant 15(3): 473-497.

- Rugini E (1984) In vitro propagation of some olive (Olea europaea L.) cultivars with different root-ability, and medium development using analytic data from developing shoots and embryos. Sci. Hort 24(2): 123-134.

- Petruccelli R, Micheli M, Proietti P, Ganino T (2012) Moltiplicazione dell’olivo e vivaismo olivicolo in Italia. Italus Hortus 19(1): 3-22.

- Rugini E, Lambardi M (2003) Micropropagation of olive (Olea europaea L.). In. Micropropagation of Woody Trees and Fruits. Jain S.M. and Ishii K. (eds.) Kluwer Academic Publishers.

- Micheli M, Standardi A, Fernandes da Silva D (2019) Encapsulation and synthetic seeds of olive (Olea europaea L.): experiences and overview. In: Synthetic Seeds: recent Trends and Future Perspectives. Faisal M, Alatar AA (Eds.) Springer Nature Switzerland, 347-361.

- Micheli M, Fernandes da Silva D, Farinelli D, Agate G, Pio R et al. (2018) Neem oil used as a “complex mixture” to improve in vitro shoot proliferation in olive. Hortscience 53(4): 531-534.

- Lambardi M, Ozudogru EA, Roncasaglia R (2013) In vitro propagation of olive (Olea europaea L.) by nodal segmentation of elongated shoots. In: Lambardi M., Ozudogru E.A. and Jain S.M. (eds). Protocols for micropropagation of selected economically-important horticultural plants, Springer New York.