Assessment of the Difficulty of the Third Molar Surgery in A Sample of the Lebanese Population

Rabih El Ghoul1, Georges Aoun2, Batol Kamar3, Georges Aad4 and Antoine Berberi5*

1Faculty of Dental Medicine, Lebanese University, Lebanon

2Department of Oral Medicine and Maxillofacial Radiology, Faculty of Dental Medicine, Lebanese University. Lebanon

3Department of Molecular Diagnostic, Faculty of Sciences, Lebanese University, Lebanon

4Clinical Assistant, Department of Oral Medicine and Maxillofacial Radiology, Faculty of Dental Medicine, Lebanese University, Lebanon

5Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Faculty of Dental Medicine, Lebanese University, Lebanon

Submission: November 14, 2022; Published: December 22, 2022

*Corresponding author: Antoine Berberi, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Dental Faculty, Lebanese University, Lebanon

How to cite this article: Rabih El G, Georges A, Batol K, Georges A, Antoine B. Assessment of the Difficulty of the Third Molar Surgery in A Sample of the Lebanese Population. JOJ scin. 2022; 3(1): 555603. DOI: 10.19080/JOJS.2022.03.555603

Abstract

Objectives: Surgical extraction of impacted third molar remains one of the most frequently performed procedures by oral and maxillofacial surgeons and represents a real challenge in complicated cases. Prediction of surgical difficulty via a thorough preoperative assessment based on demographic, operative and radiographic variables lead to a better surgical intervention with reduction of the postoperative complications. The aim of the study was to identify the predictor variables that are responsible for occurrence of surgical difficulty of impacted third molars.

Material and methods: 66 patients that attended the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery at the Lebanese University were included in the study. All demographic, operative and radiographic variables were collected from 107 impacted third molars surgically extracted. A descriptive, bivariate statistics and a multiple linear regression analysis were performed considering operation time and surgical technique as two outcome variables and indicators for surgical difficulty.

Results: The results of our study showed that surgeon experience (operative variable), periodontal membrane space, second molar relationship, root number, root morphology and depth of impaction (radiographic variables) can be used as predictor variables for surgical difficulty in maxillary third molars whilst cheek flexibility and surgeon experience (operative variables), second molar relationship, root number, bone coverage and depth of impaction (radiographic variables) can be used a predictor variables for surgical difficulty in mandibular third molars.

Conclusion: Demographic, operative and radiographic variables could be potential predictors for surgical difficulty of maxillary and mandibular third molars. Preoperative consideration of these variables helps in prediction of surgical difficulty for adequate treatment plan, to avoid postoperative morbidity and improve the level of patient’s satisfaction with the treatment received.

Keywords: Impacted third molar; Surgical difficulty; operation time; Surgical technique; Predictive factors

Introduction

Tooth impaction is a pathological situation where a tooth fails to erupt in its normal anatomical position and keeps partially or completely embedded by soft tissue or bone [1-3]. The incidence of the third molars impaction ranges from 9% to 70% with a higher percentage in the lower jaw and without sexual predilection, although some studies have showed a higher frequency in females than in males [4-7]. Eruption modifications of third molars and the continuous change of position after eruption could be affected by many factors such as nature of the diet, race, mastication and genetic predisposition [1,3].

The etiology of the third molars impaction was associated with several factors such as tooth germ malposition, lack of space in the dental arch, hereditary predisposition, lack of adequate eruption force, and interproximal attrition which causes a reduced mesial movement of the teeth leading to impaction [8,9]. Impacted third molars may remain asymptomatic indefinitely; however, they can be reason for several clinical symptoms and pathologies, such as pericoronitis, root resorption and distal caries of adjacent teeth, temporomandibular joint disorders, and odontogenic cysts and tumors around the impacted tooth with ameloblastoma being the most common tumor [4,6].

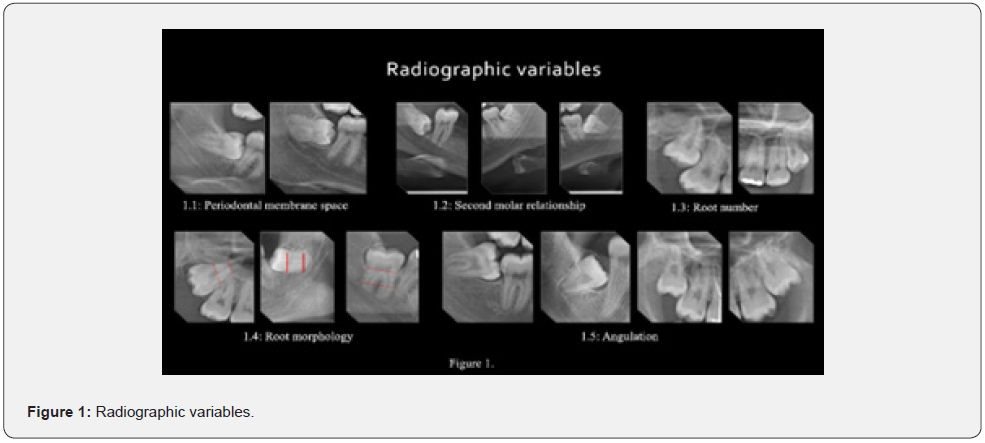

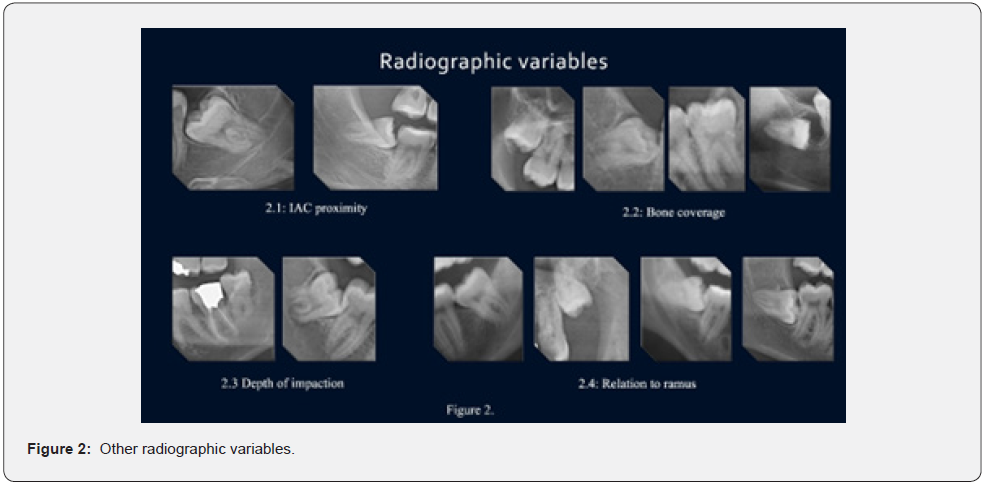

Surgical extraction of the impacted third molars is one of the most frequently performed procedures in oral and maxillofacial surgery [10-12]. To avoid surgical difficulties, a thorough preoperative assessment must be taken into consideration and for that, various methods have been proposed [13-15]. For many authors, many variables related to the teeth such as the angle and the depth of impaction, the distal space available, the root morphology, and the relationship with the inferior alveolar canal can lead to surgical difficulties [2,15-17]. Furthermore, it has been reported that the absence or the presence of a small follicular sac, the periodontal ligament width, the relation with the second molar and the close proximity with the external oblique ridge were also predictive variables of the surgical difficulty [18-20] (Figures 1 & 2). For others, the patient’s gender, age, body mass index (BMI), weight, anxiety, and ethnicity were associated with surgical difficulties [19,21]. Many researchers concluded that the patient’s age is significantly correlated with extended surgical time due to increased bone density [12,16]. Dental fear in anxious patients can make the surgical procedure of impacted mandibular third molars more complex and difficult [22].

Impaction was classified as related to soft tissue, partially or fully to bone [23]. The incidence of lingual nerve injury was found between 0.4% and 25% of cases. It may be due to the proximity of lingual cortical plate of mandibular third molar to the lingual nerve. For that, a high risk of lingual nerve injury exists during elevation of the flap medially or using the technique of lingual splitting [24]. This has been verified by several other studies where limited mouth opening and cheek flexibility in patients were determinants of difficulty in surgical extractions [20]. Surgeon’s experience can affect the course of the surgery. However, there is no universal scale to assess surgeon’s experience; it remains to be a controversial issue, while some authors have noticed that there is little variation regarding operation time between inexperienced and experienced surgeons, others confirm that operation time can directly estimate the surgical difficulty [16, 20]. The aim of this study was to identify the predictive variables that are responsible for occurrence of surgical difficulties of impacted maxillary and mandibular third molars in a group of patients treated in the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery of the Faculty of Dental Medicine at the Lebanese University.

Materials and Methods

Collection of data

A cross-sectional study was conducted in the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery at Faculty of Dental Medicine in the Lebanese University during a period of two years from March 2018 to February 2020. The study included 66 patients (ranged between 17 and 56 years old), with 107 impacted third molars (31 maxillary and 76 mandibular). Healthy patients with no relevant systemic diseases (American Society of Anesthesiologists, ASA I and ASA II classifications), and impacted third molars with root formation that has been completed were the inclusion criteria while the low quality of panoramic radiographs and impacted third molar with roots that have not completed their development yet were the exclusion criteria of this study. The indications for extraction of impacted third molars included orthodontic reason, pericoronitis, prosthetic reason, presence of cyst, discomfort, pain and prophylactic removal. The surgical extraction was performed by first, second- or third-year residents with a comparable surgical technique.

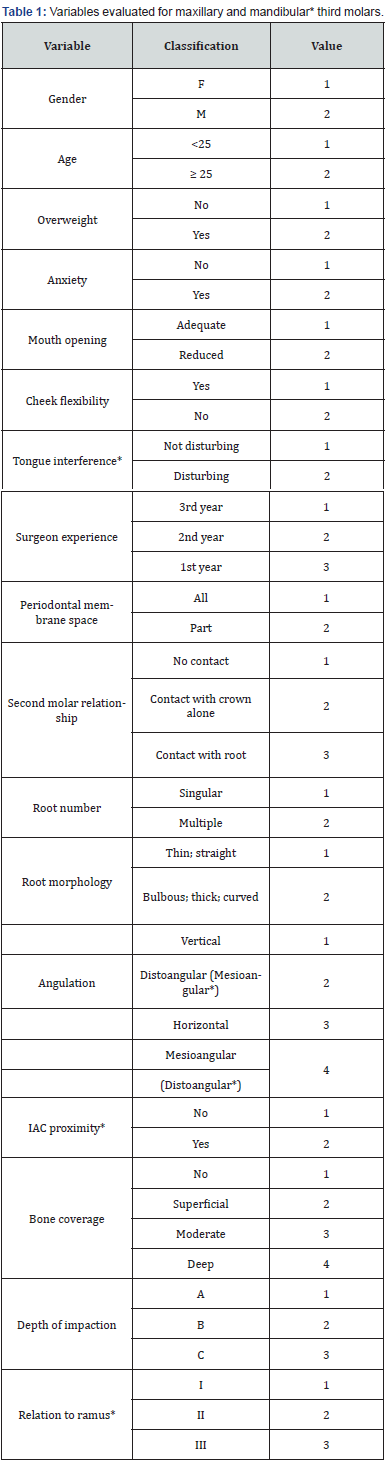

Evaluations were made of the impact of some variables on the surgical difficulty. These variables were divided into demographic, operative and radiographic variables with the demographic variables being gender, age, weight and anxiety; operative variables being mouth opening, cheek flexibility, tongue interference and resident’s experience (first, second or third year) and the radiographic variables being the periodontal membrane space, second molar relationship, root number, root morphology, angulation as classified by Winter, IAC proximity, bone coverage, depth of impaction and ramus relationship as classified by Pell and Gregory (Table 1). The panoramic radiograph of each patient was traced using Digimizer software version 5.3.5 (Medcalc viewer) and the radiographic variables mentioned above were assessed for each case.

Demographic analysis

i. Gender: the 66 patients were divided between 35 males labeled “M” and 31 females labeled “F”.

ii. Age: patients were divided into those who were <25 and those ≥ 25years of age.

iii. Weight: concerning patient’s weight, patients were divided into 2 categories: those who had overweight labeled “Yes” and those who had normal weight labeled “No”.

iv. Anxiety: anxiety was assessed according to the status of patient just before and during the surgery, when the operating resident noticed that patient had any sign of anxiety, the patient was considered anxious and labeled “Yes” or labeled “No” if he or she was not.

Operative analysis

i. Mouth opening: when mouth opening of the patient was considered sufficient for the resident in order to perform the surgery, in this case it was labeled “Adequate”; or “Reduced” if it was inadequate.

ii. Cheek flexibility: a good visibility of the vestibule and the ability for doing a good retraction of the flap without a disturbance caused by the cheek was considered as adequate flexibility of the cheek and labeled “Yes” or “No” if it was not flexible.

iii. Tongue interference: tongue size has an important effect on the comfort during surgical procedure of mandibular impacted third molar. Sometimes it was disturbing during operation labeled “Disturbing” or not disturbing labeled “Not Disturbing”.

iv. Surgeon experience: the surgical intervention was performed by first, second or third-year residents, labeled “1st year”, “2nd year” or “3rd year” respectively.

v. Radiographic analysisv

vi. Periodontal membrane space: periodontal membrane space was classified as “All” when all the space of periodontal ligament was obviously noticed around third molar on a panoramic radiograph; or as “Part” when just a part of it was noticed.

1.1. Second molar relationship: The relationship between second and third molar was classified as no contact, crown contact or root contact.

i. Root number: The third molar root was classified as singular or multiple.

ii. Root morphology: root was classified into 5 types: thin, thick, bulbous, straight and curved.

iii. Angle of impaction: third molar angulation was determined using Winter classification, as the angle formed by the long axis of third molar and the occlusal plane. Horizontal, mesioangular, vertical or distoangular impaction.

iv. IAC proximity: where mandibular third molar was closed to IAC, it was labeled “Yes” or “No” if it was distant to IAC.

v. Bone coverage: bone coverage was classified as superficial where 1 mm or less of bone was measured over the occlusal plane; moderate where the measured bone was between 1 and 3 mm; deep where more than 3 mm of bone coverage was measured and no bone coverage where absence of any bone coverage was noticed.

vi. Depth of impaction: considering Pell & Gregory classification (class A, B, C) for depth of impaction, and after a drawing an occlusal line of the first and second mandibular molars on panoramic radiograph, all maxillary and mandibular third molars were classified by comparing the highest occlusal point of third molar to the cervical line and occlusal line of the second molar.

vii. Ramus relationship: using Pell & Gregory classification for relation to ramus (scales I, II, III), all mandibular third molars were classified. The distance from the anterior border of the ramus to the distal surface of the second molar was measured followed by measuring the size of third molar crown; these two measurements were then compared.

In order to measure extraction difficulty, two outcome variables were used

i. Operation time: time required from the start of the incision to the placement of the last suture. Depending on the duration of time taken for the operation, for surgeries expected to take 30 minutes or less, 30 to 60 minutes, or 60 minutes or more, the estimated difficulty was classified as easy, moderately difficult, or difficult respectively.

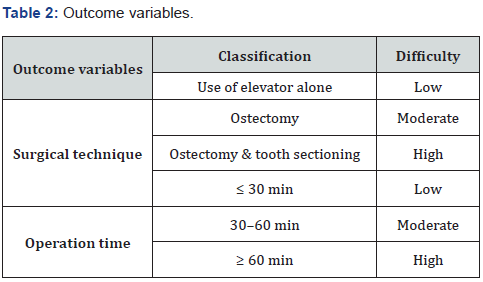

ii. Surgical technique: Depending on the technique used for extraction, operation was classified as easy when elevator alone was used; moderately difficult when elevator and ostectomy were applied; or difficult when elevator, ostectomy, and tooth sectioning were applied (Table 2).

Statistical Analysis

Data were collected from the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery at Faculty of Dental Medicine in the Lebanese University’s Microsoft Excel Sheet from March 2018 to February 2020. They were statistically analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences Software version 26.0 (SPSS, Inc., IBM Corporation).

Descriptive and bivariate statistics were computed and a model was adjusted to explain each predictor variable. A model was first adjusted for each predictor variable considering all independent variables with a level of significance up to 25% (P < .25). The adjustment of the final model was performed using a backward stepwise procedure, maintaining only those variables with a level of significance up to 5.0% (P <.05).

Results

Sixty-Six patients with a mean age of 27.75±8.81 years (ranged between 17 and 56 years), with the highest age group being ≥ 25 years, of which 35 were males and 31 were females were investigated in our study to determine the predictor variables for the operation time and the difficulty of the surgical technique. The predictor variables, including Demographic, Operative and Radiographic, were studied at different levels including their prevalence, and relationship with the outcome variables.

Prevalence of Demographic Variables.

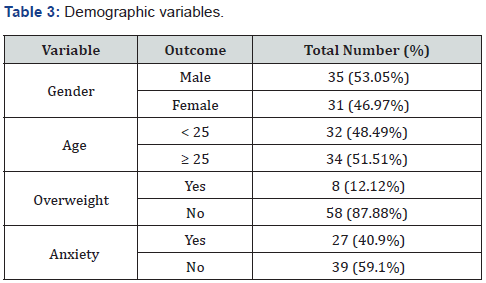

The distribution of the participants according to the different demographic variables revealed that 53.05% of them were males whilst the females composed the remaining 46.97%. Moreover, it was found that 48.49% of the patients had an age <25 whilst 51.51% had an age ≥ 25. Finally, the percentages of the patients who had overweight and anxiety were 12.12% and 40.9% respectively whilst those who were not suffering from those two conditions constituted 87.88% and 59.1%, respectively (Table 3).

Prevalence of Operative Variables.

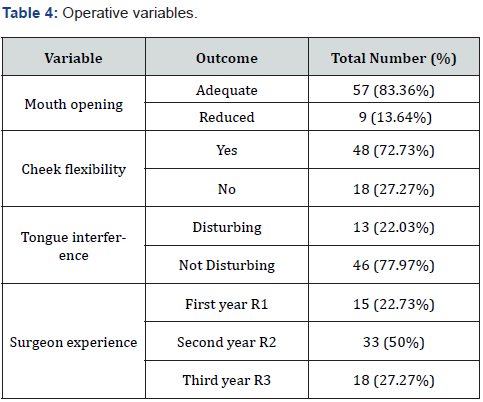

The operative variables examined in our study included mouth opening, cheek flexibility, tongue interference, and resident experience. Our analysis revealed that 83.36%, 72.73%, and 77.97% of the patients had an adequate mouth opening, flexible cheek, and a non-disturbing interfering tongue respectively. Finally, it was observed that 50% of the residents were from second year, whilst 27.27% were from the third year and 22.73% were from the first year (Table 4).

Prevalence of Radiographic Variables.

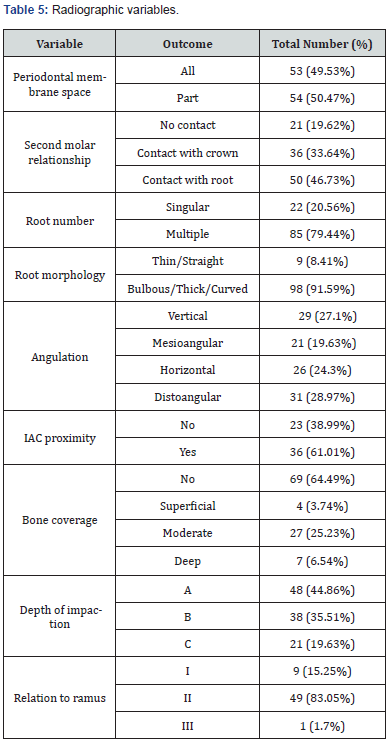

Radiographic variables were examined in the patients enrolled in this study. The outcomes of each of the above variables that were the most frequent included periodontal membrane space (Part= 50.47%), second molar relationship (Contact with the root =46.73%), root number (Multiple=79.44%), root morphology (Bulbous/Thick/Curved=91.59%), angulation (Distoangular=28.97%), IAC proximity (Yes=61.01%), bone coverage (No=64.49%), depth of impaction (A=44.86%) and relation to ramus (II=83.05%) (Table 5).

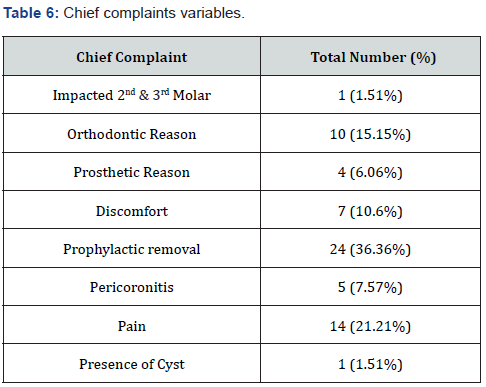

Prevalence of the complaints and outcome Variables.

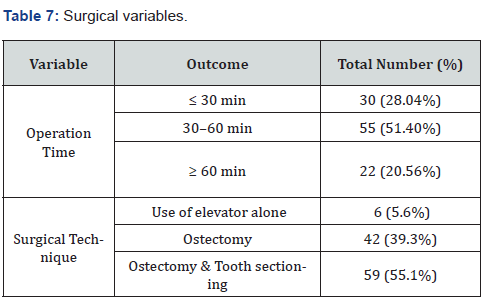

The duration of the operation time in addition to the type of the surgical technique are the two outcome variables that were recorded in our study following surgical extraction of mandibular and maxillary teeth from patients who were suffering from different complaints, among which prophylactic removal and pain were the most prevalent as shown in (Table 6). Concerning the operation time, it was found that 30–60 mins, was the most common operative time for surgical extraction (51.40%; moderate degree of difficulty), followed by < 30 mins (28.04%; low degree of difficulty) and ˃ 60 mins (20.56%; high degree of difficulty).

On the other hand, ostectomy and tooth sectioning was the most common technique for surgical extraction (55.1%; high degree of difficulty), followed by ostectomy (39.3%; moderate degree of difficulty) and the use of an elevator alone (5.6%; low degree of difficulty) (Table 7).

Relationship between potential Predictor and Outcome Variables.

To determine whether a statistically significant relationship exists between the potential predictor (Demographic, Operative, and Radiographic) and outcome variables (Type of surgical technique and its duration) which will help to determine which of those predictor variables could be of statistical significance in predicting the outcome variables, a bivariate Pearson correlation was performed between potential predictor variables and the outcome variables. Our statistical analysis results, for Maxillary teeth No 18, revealed a statistically significant correlation between, the second molar relationship (p=0.036), depth of impaction (p=0.029) and the operation time, surgeon experience and the type of surgical technique used (p=0.014). It is important to note that relationships, with p<0.25, existed between age, weight, cheek flexibility, bone coverage and the operation time in addition to others that existed between age, anxiety, cheek flexibility, second molar relationship, root number and surgical technique.

Concerning Maxillary teeth, no 28, a statistically significant correlation existed between, surgeon experience (p=0.047), depth of impaction (p=0.024) and the operation time. Other relationships, with p<0.25, existed between age, root number, root morphology, bone coverage and the operation time in addition to others that existed between age, periodontal membrane space, angulation, depth of impaction, and surgical technique. Our statistical analysis results, for Mandibular teeth No 38, revealed a statistically significant correlation between, second molar relationship (p= 0.043), relation to ramus (p=0.043) and the operation time. Other relationships, with p<0.25, existed between cheek flexibility, IAC proximity and the operation time in addition to others that existed between age, weight, cheek flexibility, tongue interference, periodontal membrane space, root morphology, IAC proximity, and surgical technique. Concerning Mandibular teeth, no 48, a statistically significant correlation existed between cheek flexibility (p=0.048) and the operation time, root number (p=0.003) and the surgical technique. Other relationships, with p<0.25, existed between surgeon experience, bone coverage, depth of impaction, and the operation time in addition to others that existed between age, anxiety, cheek flexibility, tongue interference, surgeon experience, bone coverage, depth of impaction, and surgical technique.

Determination of the statistically significant predictors for the outcome variables.

Following the identification of the potential predictor variables that have a statistically significant correlation (p<0.05) or a statistical significance (p<0.25) with our outcome variables, we proceeded to determine which of those variables can be a statistically significant predictor for each of the outcome’s variables. Thus, a multiple linear regression analysis, with the backward elimination method implicated, was performed and its results revealed that second molar relationship (Regression coefficient= -0.5; p=0.012) and depth of impaction (Regression coefficient= 0.667; p=0.01) are the two statistically significant predictor variables for the operation time in maxillary teeth No 18 whilst surgeon experience (Regression coefficient = -0.526; p=0.001) and root number (Regression coefficient= -0.468; p=0.008) are the two statistically significant predictor variables for the surgical technique. For Maxillary teeth No 28, it was found that root morphology (Regression coefficient= 0.919; p=0.004) and depth of impaction (Regression coefficient= 0.661; p=0.001) are the two statistically significant predictor variables for the operation time whilst periodontal membrane space (Regression coefficient= -0.461; p=0.044) is the only statistically significant predictor for the surgical technique.

Concerning the mandibular teeth and more specifically mandibular teeth No 38, our results revealed that second molar relationship (Regression coefficient= -0.307; p=0.043) can only be used as a statistically significant predictor for the operation time whilst cheek flexibility (Regression coefficient= 0.402; p=0.035) is the only statistically significant predictor for the surgical technique. Finally, mandibular teeth No 48 regression analysis results revealed that cheek flexibility (Regression coefficient= 0.5; p=0.048) is the only statistically significant predictor for the operation time whilst surgeon experience (Regression coefficient= 0.166; p=0.028), bone coverage (Regression coefficient= -0.111; p=0.036), depth of impaction (Regression coefficient= 0.2; p=0.025), and root number (Regression coefficient= 0.86; p=0.001) are statistically significant predictors for the surgical technique.

Discussion

One of the most performed procedures in oral and maxillofacial surgery is the surgical extraction of impacted third molars [21]. In order to minimize complications, estimation of difficulty is considered substantial to form a better treatment plan [19]. As an attempt to define the degree of surgical difficulty, classifications of impacted third molars have been proposed [19,22]. Various methods of assessment have been dominated using only radiographic variables, such as classifications submit by Pell and Gregory, Winter, Pederson and the WHARFE index expanded by Macgregor, but these classifications alone have recently been demonstrated to be insufficient for predicting difficulty and of limited clinical use [10,14,19, 21]. This showed a lack of consideration of other important variables such as patient’s gender, age, weight, body mass index (BMI), cheek flexibility, mouth opening, surgeon’s experience and many other variables [23,24]. The prediction of difficulty of impacted third molars surgery using radiographic variables alone has been questioned by Edwards et al. [10] who concluded that WHARFE index is unreliable to predict difficulty; likewise, Pell and Gregory classification, has been found to be unreliable too. In the current study, prediction of surgical difficulty of maxillary as well as mandibular third molars were investigated and a comparison of results with other similar studies in other countries was conducted.

Concerning demographic variables, the results of our study showed that relationships existed between age, weight and the operation time in addition to others that existed between age, anxiety and surgical technique in maxillary third molars. As for mandibular third molars, other relationships existed between age, weight, anxiety and surgical technique but none of these demographic variables was found as statistically significant predictor for the outcome variables. A study conducted by De Carvalho et al. [12] on a Brazilian population showed that gender, age, and weight were not significant predictors of the surgical difficulty based on the surgical technique used for impacted maxillary third molars which is in accordance with our results. On the contrary, Susarla & Dodson [25] reported gender and BMI in an American population as significant variables in determining the duration of operation in maxillary third molars while age was not a significant predictor.

In a study conducted on a Chinese population, Zhang et al. [17] found age as a determining factor of surgical difficulty of mandibular third molars. Likewise, de Carvalho and Vansconcelos in a study conducted at University of Pernambuco, Brazil [23], Alvira-González et al. [26] and Aznar et al. [22] in two studies conducted in Spain, Renton et al. [19] in a study conducted in England, Obimakinde et al. [27] and Gbotolorun et al. [28] in two studies conducted in Nigeria, they found that a longer operative time and increased surgical difficulty is related to the increase in patient age. In addition, Renton et al. [19] showed that high level of surgical difficulty was associated with people of black ethnicity.

Several authors considered age as the most predictive variable to assess surgical difficulty of mandibular third molars [12,29]. Researchers assumed that the increase in density of cortical bone, which may increase bone cutting time, can result in a long operative time and greater management during the surgery comparing to maxillary third molars where bone is much more flexible [12,16,21,24-26].

In a study conducted by Bede [21] at University of Baghdad, Iraq, age, and gender were not significantly associated with surgical time. Likewise, Roy et al. [30] in a study conducted in India and Obimakinde et al. [27] found that gender was not a predictor of difficulty which is in accordance with our results. According to some studies; an increased bone density in males relatively increased the surgical difficulty. However, female gender, where the bone thickness of the mandible is lesser than in males, was considered according to Santamaria and Arteagoitia as a risk factor [31]. In contrast with our results, Renton et al. [19] found overweight as a significant predictor associated with longer surgical time. This is accordance with the study of Alvira- González et al. [26] and the study of Carvalho and Vansconcelos [23] who concluded that weight was significantly correlated with more surgical time. Moreover, Gbotolorun et al. [28] found that BMI was a significant predictor of surgical difficulty. On the contrary, Obimakinde et al. [27] showed that weight and BMI were not predictive variables of difficulty. Fat or obese patients tend to have full and much more thickness of the cheek tissue, which may reduce visibility and restrict access thereby increasing operation time [9, 16, 21,30].

Concerning patient’s anxiety, Aznar et al. [22] concluded that prolonged surgical time and more difficult surgical interventions of mandibular third molars were significantly associated with higher degrees of preoperative anxiety which is not found significant in our results. Moreover, Balaguer-Martí et al. [32] showed that low level of patient anxiety was related to clarity of the clinical information given to the patient about the surgical procedure regarding the total intervention performed under local anesthesia, bone removal, tooth sectioning and possible complications. Regarding operative variables, our results showed that resident’s experience is the only significant predictor for the surgical technique in maxillary third molars. As for mandibular third molars, cheek flexibility is statistically significant predictor for both the operation time and the surgical technique while resident’s experience was statistically significant predictor for the surgical technique. Only a single study conducted by De Carvalho et al. [12] on maxillary third molars showed mouth opening as a predictive factor of difficulty in patients examined with a mouth opening that did not exceed 45 mm precisely. Likewise, exceeding this limit reduce visibility and manipulation of the surgical field due to the contraction of the buccinator muscle which may press the cheek facing the surgical area and requires excessive traction of the flap [16]. As for impacted mandibular third molars and similar to the findings of De Carvalho et al. [12] concerning mouth opening, a Turkish study by Komerik et al. [10], two Indian studies by Roy et al. [30] and Tenglikar et al. [20] and a British study by Renton et al. [19] all concluded that mouth opening was a significant variable of surgical difficulty. In accordance with our results, Renton et al., [19] Tenglikar et al. [20] Roy et al. [30] and Susarla and Dodson [25] demonstrated that cheek flexibility of patients has an impact over surgical time thereby surgical difficulty. In the same way, tongue interference was found as a predictive factor of surgical difficulty according to Komerik et al. [10] and Roy et al. [30].

Regarding surgical experience, our results is in agreement with other reports published by Ferrús -Torres et al. [33], Alvira- González et al. [26], Renton et al. [19] and Susarla and Dodson [25] which found a relation between difficulty and the experience level of the practitioner (i.e., fellows, residents, interns and senior surgeons). However, there is no universal classification for grading practitioner’s experience according to Akadiri and Obiechina [29]. On the other side, a study conducted by Macluskey et al. [34] in Scotland, which was in accordance with the study of Komerik et al[10]. in turkey, demonstrated that prediction of surgical difficulty using the surgical experience was unreliable. In respect to radiographic variables, our results showed that second molar relationship, root morphology and depth of impaction were predictors for the operation time while periodontal membrane space and root number were predictors for the surgical technique in maxillary third molars. As for mandibular third molars, second molar relationship can only be used as a statistically significant predictor for the operation time, while root number, bone coverage and depth of impaction are statistically significant predictors for the surgical technique. In accordance with our results concerning the space of the periodontal ligament, second molar relationship and impaction depth, De Carvalho et al. [12] found these factors as predictors of surgical difficulty in maxillary third molars: the relationship with maxillary sinus was showed as a predictive factor of difficulty but no statistical significance was reported for impaction angle, root number and root morphology.

In comparison with our results for mandibular third molars, periodontal membrane space, second molar relationship, angulation, depth of impaction and relation to ramus were demonstrated by Santamaria and Arteagoitia [31] in a study conducted in Spain as the main variables contributing to the surgical difficulty. In addition to these variables, Juodzbalys and Daugela [2] in a study conducted in Lithuania found root number and morphology as predictors of surgical difficulty, which is supported by the study of Carvalho and Vasconcelos who found the same findings [26]. Several studies in literature have reported that root number and morphology have an impact over impacted mandibular third molars. For instance, Alvira-González et al. [26] noticed that bulbous roots were associated with increasing in operation time and more difficult surgeries compared to straight roots. Curvature of roots was demonstrated by Gbotolorun et al. [28] and Tenglikar et al. [20] as statistically significant factor of operative difficulty. Moreover, root form was considered as one of the most important predictors of surgical difficulty according to Al- Samman [27] who conducted a study at the Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Department of Aleppo University, Syria and inserted the root form into their proposed scale.

Benediktsdóttir et al. [35] showed that impacted third molar with more than 2 roots was associated with more surgical time which is in contrast to the results of Tenglikar et al. [20] who found the number of roots was not significantly associated with difficulty. The findings of this study show that the angle of impaction is not a statistically significant predictor of difficulty. This is in accordance with other studies published by Bede [21], Renton et al. [19] and Gbotolorun et al. [28]. On the contrary, there was a significant association between third molar angulation and increasing in surgical difficulty according to Obimakinde et al. [27], Aznar et al. [22] and Susarla and Dodson [25]. In order to avoid nerve injury, practitioner take special care in situations where IAC is in close proximity to impacted mandibular third molar. This may lead to an increase in the operating time and thereby surgical difficulty [29]. An additional report by Maglione et al. [36-38] in a study conducted in Italy also support this idea regarding the impact of the relation between impacted mandibular third molar and inferior alveolar canal on surgical difficulty. Regarding depth of impaction as classified by Pell and Gregory, the current study showed that it was reliable to predict surgical difficulty. This is in accordance with the studies of Renton et al [19], Obimakinde et al. [21] and Aznar et al. [22] who reported that depth of impaction is a significant predictor of difficulty. Contrary to their findings, Bede [25] and Alvira-González et al. [26] did not show a significant association of depth of impaction with the duration of surgery.

The findings of the present study showed that ramus relationship was not a predictor of surgical difficulty which is in contrast to the results of Salwan Y Bede [21], Obimakinde et al. [21] and Aznar et al. [22] who showed ramus relationship as a predictor factor of difficulty. Although the difficulty of impacted maxillary third molar surgery is generally low, many inexperienced clinicians may underestimate this procedure because of the lack of publications and absence of identification of predictor variables concerning maxillary third molar surgery which increases the risk of occurrence of severe complications that oblige complex management [12,16]. The present study has some limitations. For instance, the small sample size, the level of surgical difficulty registered by a resident in a Master training program and the need for help by an instructor may not be representative in comparing to an oral surgeon with many years of experience. Moreover, additional factors, such as evaluation of radiographic variables using of a 2-dimensional panoramic radiograph when compared to CBCT which provide a better visualization and accurate assessment of variables such as the root morphology, the relationship with maxillary sinus and also with inferior alveolar canal which may not be detectable by the practitioner in a panoramic radiograph and can result in underestimation of difficulty [10,28,33,35]. Despite all the limitations mentioned above, the findings of this study confirm the results of other reports published by many authors from different countries and highlight the significance of some variables in prediction of surgical difficulty of impacted maxillary as well as mandibular third molars.

In order to determine surgical difficulty, many researchers have used operation time and surgical technique as reliable outcome variables which have been regarded as accurately estimate surgical difficulty [17,33]. Demographic, operative and radiographic variables should be taken into consideration which could determine the level of surgical difficulty in order to estimate the operative time and to adequately select the proper surgical technique for ostectomy, tooth sectioning and lifting of the roots. From the previous discussion, it would be useful to formulate a practical, simple and cost-effective index for better assessment of impacted third molar surgical difficulty and thus making better decisions that could be beneficial to the patients and inform them about possible complications after surgical intervention.

Conclusion

Impacted third molar surgery remains a debate subject and a challenge for clinicians because of various degree of difficulty among clinical cases. There is consensus of opinion regarding the impact of radiographic in combination with patient and clinical factors over difficulty of surgical extraction of impacted third molars. Regardless of its limitations and based on a statistical analysis when the operation duration and the surgical technique were used as two outcome variables for difficulty, and after a comparison of our findings with several international studies, the present study demonstrates that surgeon experience (operative variable), periodontal membrane space, second molar relationship, root number, root morphology and depth of impaction (radiographic variables) can be used as predictor variables for surgical difficulty in maxillary third molars whilst cheek flexibility and surgeon experience (operative variables), second molar relationship, root number, bone coverage and depth of impaction (radiographic variables) can predict variables for surgical difficulty in mandibular third molars. Preoperative consideration of these variables helps in prediction of surgical difficulty for adequate treatment plan, to avoid postoperative morbidity and improve the level of patient’s satisfaction with the treatment received. Further studies with bigger samples sizes will be necessary in to develop and validate an index which is based on the principal demographic, operative and radiographic predictors that intends to provide an accurate evaluation of difficulty of impacted third molar surgery.

References

- Mandal S, Pahadia M, Sahu S, Joshi A, Suryawanshi D, et.al. (2015) Clinical and imaging evaluation of third molars: a review. Journal of Applied Dental and Medical Sciences 1(3): 3-9.

- Juodzbalys G, Daugela P (2013) Mandibular third molar impaction: review of literature and a proposal of a classification. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Research 4(2): e1

- Shahbaz S, Khan M( 2017) Evaluation of mandibular third molar impaction distribution on OPG: A digital radiographic study. International Journal of Applied Dental Sciences 3(4): 393-396.

- Yilmaz S, Adisen MZ, Misirlioglu M, Yorubulut S (2016) Assessment of third molar impaction pattern and associated clinical symptoms in a central anatolian turkish population. Medical Principals and Practice 25: 169-175.

- Al-Dajani M, Abouonq AO, Almohammadi TA, Alruwaili MK, Alswilem OR et.al. (2017) A Cohort Study of the Patterns of Third Molar Impaction in Panoramic Radiographs in Saudi Population. Open Dent J 11: 648-660.

- Ryalat S, Al Ryalat SA, Kassob Z, Hassona Y, Al-Shayyab MH, et.al.(2018) Impaction of lower third molars and their association with age: radiological perspectives. Bio Med Central Oral Health Journal 18 (1): 58.

- Wazir S, Khan M, Wazir A, Manzoor S (2017) Etiology And. Pattern of impacted mandibular. Third molars - a study. Pakistan Oral & Dental Journal 37 (4): 547-550.

- Kaomongkolgit R, Tantanapornkul W (2017) Pattern of impacted third molars in thai population: retrospective radiographic survey. Journal of International Dental and Medical Research 10 (1): 30-35.

- Primo FT, Primo BT, Scheffer MAR, Hernández PAG, Rivaldo EG ( 2017) Evaluation of 1211 third molars positions according to the classification of Winter, Pell & Gregory. International Journal of Odontostomatology 11(1): 61-65

- Komerik N, Muglali M, Tas B, Selcuk U (2014) Difficulty of impacted mandibular third molar tooth removal: predictive ability of senior surgeons and residents. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 72: 1062. e1-1062.e6

- Ge J, Zheng JW, Yang C, Qian WT ( 2015) Variations in the buccal-lingual alveolar bone thickness of impacted mandibular third molar: our classification and treatment perspectives. Scientific Reports 6: 16375

- De Carvalho RWF, De Araujo Filho RCA, Do Egito Vasconcelos BC (2013) Assessment of factors associated with surgical difficulty during removal of impacted maxillary third molars. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 71: 839-845.

- Yuasa H, Kawai T, Sugiura M (2002) Classification of surgical difficulty in extracting impacted third molars. British Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 40: 26-31.

- Diniz-Freitas M, Lago-Mendez L, Gude-Sampedro F, Somoza-Martin JM, Gandara-Rey JM, et.al.(2007) Pederson scale fails to predict how difficult it will be to extract lower third molars. British Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 45: 23-26.

- Bali A, Bali D, Sharma A, Verma G (2013) Is Pederson Index a True Predictive Difficulty Index for Impacted Mandibular Third Molar Surgery? A Meta-analysis. Journal of Maxillofacial and Oral Surgery 12(3): 359-364

- Sánchez-Torres A, Soler-Capdevila J, Ustrell-Barral M, Gay-Escoda C (2019) Patient, radiological, and operative factors associated with surgical difficulty in the extraction of third molars: a systematic review. International Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 49(5): 655-665

- Zhang X, Wang L, Gao Z, Li J, Shan Z (2019) Development of a new index to assess the difficulty level of surgical removal of impacted mandibular third molars in an asian population. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 77: 1358. e1-1358.e8

- Dhuvad Jigar M, Shah Jay C, Anchlia Sonal M (2017) A novel proforma for clinical and radiographic evaluation of impacted third molars prior to surgical removal. International Journal of Medical Research & Health Sciences 6(2): 11-19

- Renton T, Smeeton N, McGurk M (2001) Factors predictive of difficulty of mandibular third molar surgery. British Dental Journal. 190:11.

- Tenglikar P, Munnangi A, Mangalgi A, Uddin SF, Mathpathi S, (2017) An assessment of factors influencing the difficulty in third molar surgery. Annals of Maxillofacial Surgery 7: 45-50

- Bede SY. Factors affecting the duration of surgical extraction. of impacted mandibular third molars. World Journal of Dentistry. 2018; 9: 8-12.

- Aznar-Arasa L, Figueiredo R, Valmaseda-Castello´n E, Gay-Escoda C (2014) Patient anxiety and surgical difficulty in impacted lower third molar extractions: a prospective cohort study. International Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 43(9): 1131-1136.

- de Carvalho RW, Vasconcelos BC (2017)Pernambuco index: predictability of the complexity of surgery for impacted lower third molars. International Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 47(2): 234-240.

- Al-Samman AA (2017)Evaluation of Kharma scale as a predictor of lower third molar extraction difficulty. Medicina Oral Patologia Oral y Cirugia Bucal 22 (6): e796-799.

- Susarla SM, Dodson TB (2013)Predicting third molar surgery operative time: a validated model. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 71: 5-13.

- Alvira-González J, Figueiredo R, Valmaseda-Castellón E, Quesada-Gómez C, Gay-Escoda C (2017) Predictive factors of difficulty in lower third molar extraction: A prospective cohort study. Medicina Oral Patologia Oral y Cirugia Bucal 22(1): 108-114.

- Obimakinde OS, Okoje VN, Ijarogbe OA, Obimakinde AM (2013) Role of patients' demographic characteristics and spatial orientation in predicting operative difficulty of impacted mandibular third molar. Annals of Medical and Health Sciences Research 3: 81-84.

- Gbotolorun OM, Arotiba GT, Ladeinde AL (2007) Assessment of factors associated with surgical difficulty in impacted mandibular third molar extraction. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 65(10): 1977-1983.

- Akadiri O, Obiechina AE (2009) Assessment of difficulty in third molar surgery-a systematic review. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 67(4): 771-774

- Roy I, Baliga SD, Louis ARS, Rao S (2015) Importance of clinical and radiological parameters in assessment of surgical difficulty in removal of impacted mandibular 3rd molars: a new index. Journal of Maxillofacial and Oral Surgery 14: 745-749.

- Santamaria J, Arteagoitia I (1997) Radiologic variables of clinical significance in the extraction of impacted mandibular third molars. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 84: 469-473.

- Balaguer-Martí JC, Aloy-Prósper A, Peñarrocha-Oltra A, Peñarrocha-Diago M. Non surgical predicting factors for patient satisfaction after third molar surgery. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 21(2): e201-205.

- Ferrús-Torres E, Gargallo-Albiol J, Berini-Aytés L, Gay-Escoda C (2009) Diagnostic predictability of digital versus conventional panoramic radiographs in the presurgical evaluation of impacted mandibular third molars. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 38(11): 1184-1187.

- Macluskey M, Slevin M, Curran M, Nesbitt R (2005) Indications for and anticipated difficulty of third molar surgery: a comparison between a dental hospital and a specialist high street practice. Br Dent J 199(10): 671-675.

- Benediktsdóttir IS, Wenzel A, Petersen JK, Hintze H (2004) Mandibular third molar removal: risk indicators for extended operation time, postoperative pain, and complications. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 97(4): 438-46

- Maglione M, Costantinides F, Bazzocchi G (2015) Classification of impacted mandibular third molars on cone-beam CT images. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Dentistry 7(2): e224-231.

- Santosh P(2015) Impacted mandibular third molars: review of literature and a proposal of a combined clinical and radiological classification. Annals of Medical and Health Sciences Research 5(4): 229-234.

- Sammartino G, Gasparro R, Marenzi G, Trosino O, Mariniello M, et al. (2017) Extraction of mandibular third molars: proposal of a new scale of difficulty. British Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 55(9): 952-957.