Application of the Kano Model in Understanding Consumer Preferences and Product Attributes in the Vacation Ownership Industry

Amy Gregory*

Associate Professor, Rosen College of Hospitality Management, University of Central Florida, United States

Submission: April 10, 2021; Published: April 28, 2021

*Corresponding author: Amy Gregory, Associate Professor, Rosen College of Hospitality Management, University of Central Florida, 9907 Universal Blvd, Orlando, FL 32819, United States

How to cite this article: Amy G. Application of the Kano Model in Understanding Consumer Preferences and Product Attributes in the Vacation Ownership Industry. JOJ scin. 2021; 2(4): 555592. DOI: 10.19080/JOJS.2021.01.555592

Abstract

From the premise that not all attributes are equal in terms of their effect on overall customer satisfaction or that different customer segments may value product attributes differently, the current research proposes a model that may be used to classify product attributes within the services industry and augments the traditional method of data analysis to improve the efficacy of the information gathered. The research context is vacation ownership – reportedly the fastest growing lodging segment yet a relatively under-researched area. In a two-pronged approach, this study explored two distinct aspects of the vacation ownership experience: the purchase process and the use of the product. This study identified attributes of the vacation ownership product that are positively related to customer satisfaction (personal sales techniques, incentives, amenities, exchange benefits, hotel program affiliation, vacation counselors) and those that had no incremental effect on product satisfaction (financing, organized activities). This research could be considered unique as it is a comprehensive view into customer preference related to both the purchase and the consumption of a vacation product and provides a model for consumer preference that could be more widely applied across lodging products. As a result, an additional contribution could be the establishment of a benchmark for future studies.

Keywords: Kano Model, Customer satisfaction, Consumer preference, Vacation ownership, Timeshare

Introduction

The ongoing pursuit of understanding how consumers’ expectations can be achieved or exceeded has long been an area of interest for academics and practitioners alike. The consensus appears to support the thinking that higher satisfaction is better for long-term survival and success. But this may not hold true when one considers that not all attributes of a product are equal in terms of their effect on overall customer satisfaction. From this premise, this research proposes and applies a model that may be used to classify product attributes within the services industry. The theoretical foundation of the study is based on the Kano Model, a research model that has been widely applied across a variety of industries and products.

Despite the prominence of the vacation ownership industry, relatively little academic research exists in this area. While vacation ownership owners are generally satisfied with their product [1], it appears as if academic research has not differentiated vacation ownership product attributes according to their expected impact on satisfaction levels or consumer preference. This differentiation of attributes may allow for increased satisfaction with the product, product positioning, and product development strategies. In fact, industry executives report that declining effectiveness of current sales and marketing practices is one of their greatest concerns in the industry [2].

Literature Review

According to Heung and Ngai [3], customer satisfaction is a key mediator for perceived value and customer loyalty. In the lodging industry, it has been suggested that individual satisfaction is paramount enough to command substantial presence within personal accounts volunteered by consumers [4]. And many have suggested that satisfying the customer is a fundamental requirement for business success [5-8]. Researchers have measured customer satisfaction and categorized attributes according to their fulfillment of minimum requirements or additive value [9]. Gallarza & Saura [10] suggested that quality is a precursor of perceived value, and satisfaction is the behavioral consequence of the value expectation. This is consistent with much earlier research conducted by Howard & Sheth [11]and Kotler & Levy [12]. It is from this premise that the current researchers have attempted to determine how specific product attributes, or attribute types, relate to satisfaction and/or dissatisfaction in the vacation ownership industry

The Kano Model

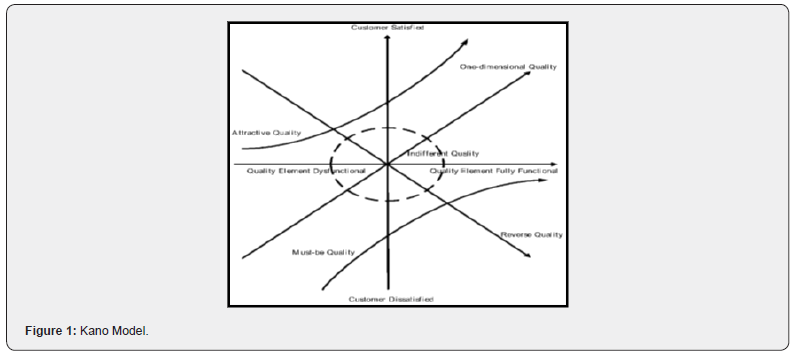

In 1984, Kano, Seraku, Takahashi & Tsuji [13] surmised that certain attributes may produce higher satisfaction and that consumers may have differing requirements as to the functional attributes of products. According to Kano, et al., [13] understanding the functional requirements of a product attribute in addition to the satisfaction rating, could reveal the origin of customer satisfaction, as well as the features or attributes that a company should focus on in order to be competitive, increase customer satisfaction, or to differentiate themselves within the marketplace [13]. This multi-dimensional measurement provides the basis for Kano’s Model (Figure 1) which plots satisfaction on the y axis, attribute performance on the x axis, and reveals the predicted effect on satisfaction based on expectations of the attribute. Kano [13] suggested that by evaluating the frequency of the responses of two answers to each of the functional and dysfunctional questions jointly, the product features could be classified. From this premise, Kano et al. challenged the traditional customer satisfaction models through a suggestion that more specific origins of customer satisfaction could be understood by uncovering the product requirements as well as the satisfaction ratings of customers.

Kano’s Model has been applied widely within academic research [14-21] and within a variety of contexts such as manufactured consumer products [22], consumer services including banking, cleaning services, restaurants, and grocery stores [19], the retail ski product industry [23], studies in employee satisfaction [6] and student/professor satisfaction [15], as well as transportation [24-26]. Most recently, [27] demonstrated how the results of the Kano Model could direct lodging providers toward continuing, outsourcing, or discontinuing certain components of their product offering in an effort to reduce costs for both the provider and the consumer. Application of the Kano Model has furthered satisfaction research in a variety of contexts, including the lodging industry. As a result, one could conclude that advancement of the model may also be appropriate for the vacation ownership segment of the lodging industry

The Vacation Ownership Industry

The vacation ownership (also referred to as timeshare) product is defined as a real estate product that provides for a week (or its equivalent) of ownership in “lavish resort accommodations.” The vacation ownership segment of the hospitality industry is a large and rapidly growing segment [27-31]. In fact, the timeshare segment has been recognized as the fastest growing segment of the travel industry realizing double-digit compound annual growth rates over the last twenty years [27]. According to a 2020 economic impact study sponsored by American Resorts Development Association (ARDA), the Washington DC based vacation ownership and resort development industry representative, the timeshare industry contributed an estimated $80 billion of output to the U.S. economy in 2019; including 465,800 full and part time jobs; $22 billion in salaries, wages, and related income, as well as approximately $8.3 billion in tax revenues. According to ARDA’s 2020 State of the Timeshare Industry annual report (www.arda. org), there were 1,548 vacation ownership resorts in the United States representing 7.2 million equivalent weeks of vacations owned by more than 4.7 million individuals. In 2019, U.S. sales totaled $7.4 billion dollars representing approximately 60% of the worldwide timeshare sales volume.

Existing research on vacation ownership is limited, and few studies have been published on amenities offered by timeshare companies. Lawton, Weaver, & Faulkner [32] concluded that the onsite and nearby amenities, children’s activities, and entertainment options associated with timeshare resorts in Australia added to the satisfaction level of timeshare owners. In a study on timeshare resorts in the United States’ Carolinas, the fourth largest geographic U.S. market in terms of concentration of timeshare resorts, Stringam [2] determined that amenities related to timeshare resorts were comparable with amenities offered in resort lodging properties. According to Stringam [2], the following were listed as the most common amenities associated with timeshare resorts: swimming pools, exercise rooms, children’s activities, and tennis courts for onsite amenities; WIFI internet access, DVD players, and CD players for in-unit amenities.

In an effort to address the unique complexities of vacation ownership, Sparks, Butcher, and Pan [33] note that the timeshare product is comprised of both experiential and ownership components. Their 2007 study was specifically focused to determine value that was attached to the experience and ownership components of the timeshare product. In an unmatched approach based upon the fact that the purchase of vacation ownership is a long-term investment and thereby may invoke strong feelings of value, the authors used a qualitative approach to determine which dimensions of value relate specifically to vacation ownership. Their study revealed that the purchase of vacation ownership product includes seven important attributes: ownership pride, financial outlay, vacation flexibility, gift, luxury, personal reward, and exposure to new experiences. Considering the current shortage of published research and the industry’s concern for declining sales in the vacation ownership industry, it appears there is a need for research providing insight into consumers’ preferences for the vacation ownership product. More specifically, this research particularly addresses two questions: 1) does consumer satisfaction for the vacation ownership product vary based on the presence (or absence) of particular attributes and 2) does consumer preference for the vacation ownership product vary by attribute.

Conceptual Framework

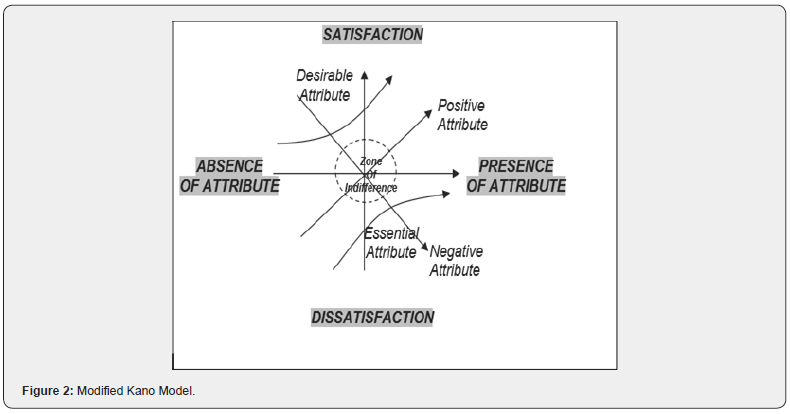

The conceptual framework of this study adopts a quantitative approach designed to categorize the various attributes of the vacation ownership product according to their anticipated effect on customer satisfaction. As noted in section 2.1, the Kano Model has been used in a variety of applications and industries to effectively accomplish this objective [14, 16, 17, 18, 19, 21, 23]. Because the Kano Model was initially developed for and subsequently adopted by the manufacturing industry during an era of product development and competitive differentiation, [6, 19, 22, 24], modification of the model may make it more appropriate for application to services and the greater hospitality industry. Further, research in satisfaction has focused on the attribute level through analysis of specific attributes that drive overall satisfaction and the relationship to consumers’ activities, attitudes, demographic profiles, or company profitability, [34-36]. Thus, it seems appropriate to modify the Kano Model to measure satisfaction and presence (or absence) of a particular attribute instead of the functional/ dysfunctional quality of that attribute. In fact, Kano [13] clearly referred to his own model attributes as having or lacking certain functions or features. Thus, a modified Kano model has been adapted for the current study (Figure 2).

Applying the Framework to the Vacation Ownership Product

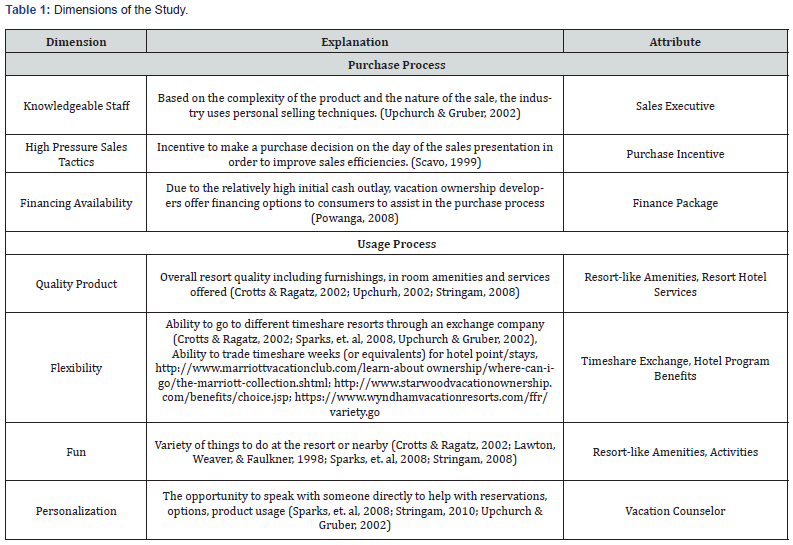

Existing academic literature on vacation ownership reveals two primary areas of focus each with their related attributes: the purchase process [37-39], and the usage/experience process [1, 2, 31-33, 37]. The dimensions identified in academic literature were examined and validated by industry professionals to ensure that no items had been overlooked. Table1 consolidates the various dimensions and specific attributes related to the vacation ownership product.

Methodology

This research examined consumer’s requirements and preferences for particular attributes of the vacation ownership product during the purchase process and usage process. The chosen sample frame includes current owners of vacation ownership product in the United States selected through a random sampling process of owners associated with one of the largest vacation ownership companies in the United States.

The survey instrument was delivered in an online format and was consistent with previous studies using the Kano Model. More specifically, respondents were asked to choose from one of five categorical responses for two statements related to each of the study attributes. These statements were differentiated only by the fact that one related to the presence of the attribute (“How would you feel if the product had the attribute?”) and the other related to the absence of the attribute (“How would you feel if the product did not have the attribute?”). Respondents chose from five categorical responses for attribute functionality: like, mustbe, neutral, live with, dislike for both statements.

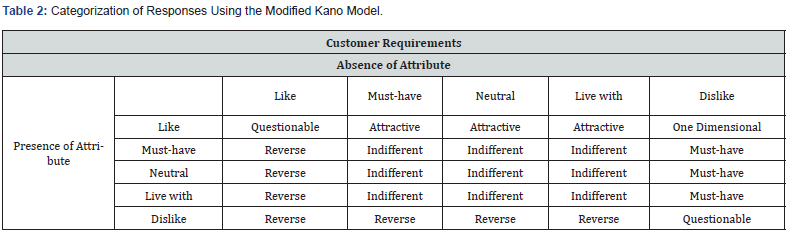

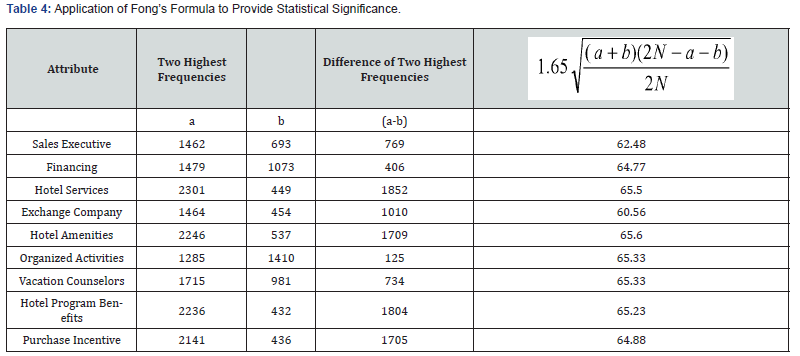

Kano [13] suggested that customer responses to functional (having the attribute) and dysfunctional (not having the attribute) statements, could then be sorted into one of five categories. By evaluating the frequency of the responses of two answers to each of the functional and dysfunctional questions jointly, the product features could be classified using the Kano Model. For example, if the answer provided for the functional form of the question (If the vacation ownership company provides resort-like amenities, how do you feel?) was “I like it that way” and that answer is evaluated with the response on the dysfunctional form of the question (If the vacation ownership company does not provide resort-like amenities, how do you feel?), such as “I dislike it this way”, the Kano Model would suggest that the presence of this attribute is positively related to satisfaction. Table 2 provides a complete categorization of responses. The data collected was tallied in a fashion consistent with previous studies using the Kano Model. To provide further statistical support, additional computations were performed using a formula introduced by Fong [40]. To quote Fong [40], “to determine the statistical significance of Kano responses at 90% confidence level, when a and b are the frequencies of the two most frequent observations and N is the total number of responses, the null hypothesis is defined as H0: a – b = 0, and the alternative hypothesis as H1: a – b > 0.” Therefore,

Results

A random sampling of 20,000 vacation ownership owners of one of the largest vacation ownership companies were invited to participate in the survey. The survey invitation originated directly from the vacation ownership company and contained a web link for the survey. Approximately 31% (6,266) of the individuals accessed the survey with 3,231 individuals completing the survey: representing a 16% response rate. Of the 3,231 completed surveys, respondents in this study were primarily male (62%); 38% of the study respondents were female. The large majority of the respondents were married (82%). Nearly 62% of the respondents have children present in the home. The mean age of respondents was 59.7, with the largest percentage of respondents being 55 to 64 years of age. The mean household income of the respondents was $170,630. The respondents in the study are educated with 59% having completed college and another 23% reporting completion of a post graduate degree. Finally, the majority of respondents (57.9%) own one or more weeks of timeshare with more than one company, and 14% of study respondents report owning two or more weeks with more than one timeshare company.

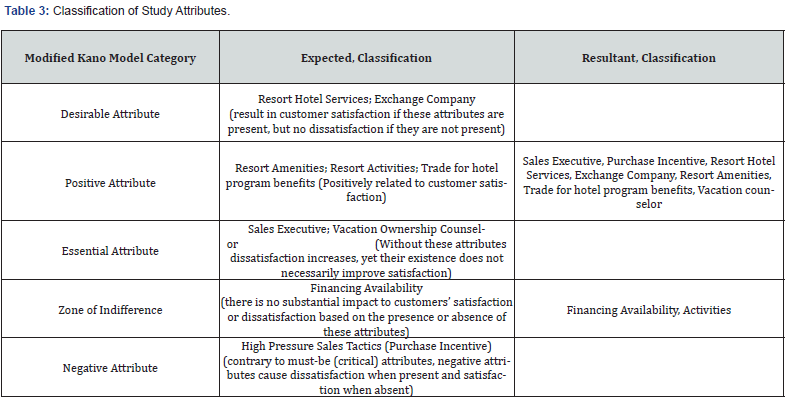

As anticipated, attributes that had been identified previously in literature were categorized differently using the Kano questionnaire and Modified Kano Model. Table 3 provides the expected and resultant classification of the attributes included in this research study. Table 4 provides statistical support for the significance of the findings using Fong’s formula. Consistent with previous studies [1, 2, 31-33, 41, 42], this research suggests that vacation ownership owners are satisfied with the usage components of the product purchased. This is evident in the consumer categorization of attributes included in this study as “positive attributes – those that are positively related to satisfaction.” In addition, this study advances existing research by demonstrating that vacation ownership owners are also satisfied with many of the attributes related to the purchase of the product. Interestingly enough, even the attribute hypothesized to be categorized as a negative attribute (purchase incentive due to its expected effect on dissatisfaction, rather than satisfaction) was perceived favorably by owners of the product included in this research. Lastly, the research also lends support to a conclusion that companies in the vacation ownership industry have identified and delivered upon the attributes (positive attributes) of the product that are related to increased satisfaction.

Discussion & Suggestions

The attributes included in this study were either classified as being positively related to satisfaction or as having no substantial impact to customers’ satisfaction or dissatisfaction. This may suggest that the attributes included in this study and previous research are basic features that attend to the minimum requirements of the customers. While minimum requirements consist of all basic features along with elements and processes that attend to minimal expectations and demands of customers; features that add value allow the provider to exceed consumer expectations by providing them, yet the absence of these features may not work negatively against the provider [23, 43].

This study identified attributes of the vacation ownership product that are positively related to customer satisfaction that had not been identified in previous research:

i. a sales executive to guide the prospective purchaser through the sales process,

ii. a purchase incentive

iii. ability to trade for hotel program benefits.

The presence of a sales executive during the purchase process was categorized as a positive attribute; meaning that owners of the product like having a sales executive take them through a personalized sales presentation and do not like it when this is not available. Implications for the industry, based on this finding, suggest that the current personalized selling approach works for the majority of customers. However, approximately 20% of the respondents were neutral to the presence (and absence) of a sales executive during the sales presentation. This may be due to the long-term ownership (greater than 10 years on average for study respondents), multiple weeks of ownership with one or more companies, or the average age of the respondents (59.7). Nonetheless, opportunity may exist for exploration of alternate sales methods for some customer segments [44-47].

The results of this study also indicate that the industry practice of providing purchase incentives is also positively related to customer satisfaction. However, what is of essential interest here is that while the overwhelming majority of respondents like having a purchase incentive (67%), the responses are more segmented when asked how they feel if a purchase incentive is not available. One would expect, based on the large percentage of those that like it that way, that the responses related to not having a purchase incentive would be similar. In fact, the results are more varied. While the majority do not like it when a purchase incentive is not available, 20% can live with it that way and 30% are neutral. This suggests that consumers may be conditioned to the presence of a purchase incentive since it is industry practice to provide incentives for all purchasers, not just first-time buyers. Alternatively, the longer term of ownership or multiple week ownership represented in this study may be an influencer in the respondents’ answers. However, if nearly 50% of the respondents in this survey do not require a purchase incentive in order to be satisfied with the product, individual companies and perhaps the industry may be able to move off this practice over time, thereby reducing sales costs and shedding one of the more negative aspects of the product as reported widely in the media and as perceived by consumers in general. It would be important for practitioners to understand which consumers do not require a purchase incentive to ensure that elimination or restructuring of this component of the sales process does not negatively impact sales [48-51].

Also related to the sales process and a unique contribution to existing research, the presence of an option to participate in hotel program benefits through the exchange of the annual timeshare ownership is a popular facet of satisfaction according to this study. This may be influenced by the preponderance of study participants that owned with a company offering such benefits, or it may be related to the multiple company ownership of many respondents included in the study. Given that the ratings on this attribute were among the highest in terms of concentration of responses, practitioners would be well served to further explore this feature. More specifically, it may not be enough to offer a program that allows an owner to trade for alternate accommodations or vacations, but the responses to this attribute may be influenced by other factors related to the brand or consumer behavior driven by brand loyalty, familiarity, longevity, etc.

This study also confirmed what has been identified in previous research. The following attributes of the product are positively related to customer satisfaction:

i. resort-like hotel services, i.e., concierge

ii. resort amenities, i.e., fitness center

iii. affiliation with an exchange company

iv. a vacation counselor to assist with vacation planning.

This is not surprising since vacation ownership resort development has strived to construct accommodations and resorts that are purpose built, four- and five-star accommodations. Such improvements in the physical product and service levels are reportedly due to the presence of the primary lodging brands in the segment or are in order to gain the necessary approvals and ratings from the timeshare exchange companies. Respondents in the study had a strong preference for the presence of a vacation counselor to assist with vacation planning. More than 66% of the respondents prefer the presence of a vacation counselor and the findings indicate that this feature of the product is positively related to product satisfaction. On the other hand, nearly 30% of the respondents are neutral if a vacation counselor is not provided. Since maintaining a staff of individuals to assist owners with their vacation planning can be costly, the industry should attempt to consider outsourcing, understand which owners may not be adversely impacted by the lack of a vacation counselor to assist with planning or identify owner segments who may be willing to pay for such a benefit.

As additional insight and as a result of the Kano method, one can now understand that certain attributes may neither add to the satisfaction or dissatisfaction with the vacation ownership product. The following attributes were categorized by the majority of the research study respondents as neither adding to their satisfaction or dissatisfaction with the product:

i. Availability of a finance package

ii. Presence of onsite activities

This is a surprising finding and may be explained by the fact that most of the vacation ownership owners are usually financially secure and capable of securing financing on their own. Similarly, the high disposable incomes of vacation ownership owners do not typically require organized activities as they are capable and can afford to choose them from the surrounding community. While both attributes may provide additional income for vacation ownership companies, they could possibly be outsourced or perhaps the terms could be restructured to be more attractive in order to increase owner interest and activity related to these product attributes. Specific to organized activities, the presence of children and the ages of those children attached to respondents in this study may be an influencing factor in how respondents responded to this particular attribute. Also, based on the longer term of ownership, perhaps those included in the study are familiar enough with the locations accessed that they no longer require onsite activities in order to entertain them in the destinations. Further, if organized activities are not “refreshed” regularly, owners may grow accustomed to the offerings and may not be repeatedly enjoying them. Practitioners should consider attendance levels of the various activities and the money and resources spent against them to ensure that they are providing value.

Importantly none of the attributes in the study were classified as those that offer a point of differentiation. Further exploratory research could be done to uncover attributes of the vacation ownership product that are attractive (increase satisfaction when present, but do not negatively impact satisfaction when absent) to consumers. Delivering upon these attributes may increase satisfaction and provide a positioning strategy for the industry going forward as it seeks to attract new customers and retain the satisfaction levels of its current customers.

Limitations

Although the company providing the random sampling of respondents is among the largest for number of owners, operating units, and annual sales volumes, it is possible that participants’ responses could be affected by the characteristics of the company, and perhaps the experience of the product offered by that company. However, this effect is perhaps minimized due to the representation of respondents who own one or more weeks of vacation ownership with a company other than the one introducing the respondent to the survey. Due to the intended comprehensive nature of the study, the research was gathered by asking participants to recall information from previous vacation ownership purchase and usage processes. It is possible then that recall may be impacted by uncontrollable factors. Attributes utilized in the study were gathered from previous research and industry input. While extensive efforts were made to compile an exhaustive list, it is possible that the attribute list is not comprehensive. For the aforementioned reasons, the findings of this study should be generalized with care. Replication of the study to uncover excluded attributes and to validate the findings would address the limitations identified.

References

- Crotts J & Ragatz R (2002) Recent US timeshare purchasers: Who are they, what are they buying, and how can they be reached? International Journal of Hospitality Management 21(3): 227-238.

- Stringam B (2008) A comparison of vacation ownership amenities with hotel and resort amenities. Journal of Retail and Leisure Property 7(3): 186-203.

- Heung V, Ngai E (2008) The mediating effects of perceived value and customer satisfaction on customer loyalty in the Chinese restaurant setting. Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality and Tourism 9(2): 85-107.

- Maoz D (2004) The conquerors and the settlers: Two groups of young Israeli backpackers in India. The Global Nomad. Clevedon, UK: Channel View :109-122.

- Anderson E, Fornell C, Lehmann D (1994) Customer satisfaction, market share, and

Journal of Marketing 58(3): 53-66. - Matzler K, Fuchs M, Schubert A (2004) Employee satisfaction: Does Kano’s model apply? Total Quality Management & Business Excellence 15(9-10): 1179-1198.

- Oliver R L (1999) Whence consumer loyalty? Journal of Marketing 63(4): 33-44.

- Yi Y (1990) A critical review of consumer satisfaction. Review of Marketing 4: 68-123.

- Churchill G, Surprenant C (1982) An investigation into the determinants of customer satisfaction. Journal of Marketing Research 19(4, Special Issue on Causal Modeling): 491-504.

- Gallarza M, Saura I (2006) Value dimensions, perceived value, satisfaction and loyalty: An investigation of university students’ travel behaviour. Tourism Management 27(3): 437-452.

- Howard J, Sheth J (1969) The theory of buyer behavior. New York, NY. John Wiley & Sons, Inc

- Kotler P, Levy S (1969) Broadening the concept of marketing. Journal of Marketing 33(1): 10-15.

- Kano N, Seraku N, Takahashi F, Tsuji S (1984) Attractive quality and must-be quality. Hinshitsu: The Journal of the Japanese Society for Quality Control 14(2): 39-48.

- Bhattacharyya S, Rahman Z (2004) Capturing the customer's voice, the centerpiece of

strategy making: A case study in banking. European Business Review 16(2): 128-138. - Emery C (2006) An examination of professor expectations based on the Kano model of customer satisfaction. Academy of Educational Leadership Journal: 10(1): 11.

- Emery C, Tian R (2002) Schoolwork as products, professors as customers: A practical teaching approach in business education. Journal of Education for Business 78(2): 97-102.

- Emery C, Tolbert S (2003) Using the Kano model of customer satisfaction to define and communicate supervisor expectations. Allied Academies International Conference. Academy of Organizational Culture, Communications and Conflict. Proceedings 8(1): 7.

- Fuller J, Matzler K (2007) Virtual product experience and customer participation - A chance for customer-centered, really new products. Technovation 27(6): 378-387.

- Schvaneveldt S, Enhawa T, Miyakawa N (1991) Consumer evaluation perspectives of service quality: Evaluation factors and two-way model of quality. Total Quality Management 2(2): 149-161.

- Wang T, Ji P (2010) Understanding customer needs through quantitative analysis of Kano's model. The International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management 27(2): 173-184.

- Yang C (2003) Establishment and applications of the integrated model of service quality measurement. Managing Service Quality 13(4): 310-324.

- Miyakawa M, Wong C (1989) Analysis of attractive quality and must-be quality through product expectation factors. Proceedings of 35th Technical Conference, Tokyo. Society for Quality Control: 101-104.

- Kurt Matzler, Hinterhuber H (1998) How to make product development projects more successful by integrating Kano’s model of customer satisfaction into quality function deployment. Technovation 18(1): 25-38.

- Silvestro R, Johnston R (1990) The determinants of service quality: hygiene and enhancing factors. Quality in Services II, Selected Papers. Warwick Business School, UK.

- Shahin A (2004) Integration of FMEA and the Kano model: An exploratory examination. The International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management 21(6/7): 731-746.

- Shahin A, Zairi M (2009) Kano model: A dynamic approach for classifying and prioritizing requirements of airline travelers with three case studies on international airlines. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence 20(9): 1003-1028.

- ARDA International Foundation (2014) Timeshare Industry Resource Manual. Washington,

DC: American Resort Development Association. - Gregory A Weinland J (2016) Timeshare research: A synthesis of forty years of publications. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 28(3): 438-470.

- Panela D, Morais A, Gregory A (2019) An analytical inquiry on timeshare research: A continuously growing segment in the hospitality industry. International Journal of Hospitality Management 76: 132-151.

- Ragatz R (2007) Timeshare facts and figures, accessed 13 March 2009.

- Upchurch R, Gruber K (2002) The evolution of a sleeping giant: Resort timesharing. The International Journal of Hospitality Management 21(3): 211-225.

- Lawton L, Weaver D, Faulkner B (1998) Customer satisfaction in the Australian timeshare industry. Journal of Travel Research 37(1): 28-36.

- Sparks B, Butcher K, Bradley G (2008) Dimensions and correlates of consumer value: an application to the timeshare industry. International Journal of Hospitality Management 27: 98-108.

- Orsingher C, Marzocchi GL (2003) Hierarchical representation of satisfactory consumer service experience. International Journal of Service Industry Management 14(2): 200-216.

- Poon W, Yong G (2005) Comparing satisfaction levels of Asian and western travelers using Malaysian hotels. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Management 12(1): 64-79.

- Ryan C, Huimin G (2007) Perceptions of Chinese Hotels. Cornell Hotel & Restaurant Administration Quarterly 48(4): 380-391.

- Powanga A, Powanga L (2008) An economic analysis of a timeshare ownership. Journal of Retail & Leisure Property 7(1): 69-83.

- Scavo J (1999) Marketing resort timeshares: The rules of the game. St. John’s Law Review 73(1): 217-245.

- Betsy B Stringam (2010). Timeshare and vacation ownership executives’ analysis of the industry and the future. Journal of Retail & Leisure Property 9(1): 37 – 54.

- Fong D (1996) Using the self-stated importance questionnaire to interpret Kano questionnaire results. Center for Quality Management Journal 5(3): 21-23.

- Kaufman T, Upchurch R (2007) Vacation ownership: Gender positioning. Journal of Leisure and Retail Property Management 6(1): 8-14.

- Beverley Sparks, Butcher K, Pan G (2007) Customer derived value: Understanding the meaning in the resort ownership industry. The Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly 48(1): 28-45.

- Maddox R (1981) Two-factor theory and consumer satisfaction: replication and extension. Journal of Consumer Research 8(1): 97-102.

- American Resort Development Association (ARDA) (2019). Industry fact sheet.

- Gilligan E (2006) The time has come: Demand surges for timeshare resort properties. Commercial Property News 20(2): 16-19.

- Hayward P (2005) Lodging’s 4th dimension: Alternative lodging is becoming an ever-growing aspect of the industry landscape. Lodging Magazine 31(1): 26-31.

- Pawitra T, Tan K (2003) Tourist satisfaction in Singapore--a perspective from Indonesian tourists. Managing Service Quality 13(5): 399-411.

- Small J (2003) Voices of older women tourists. Tourism Recreation Research 28(2): 31-39.

- Tan K, Shen X (2000) Integrating Kano’s model in the planning matrix of quality function deployment. Total Quality Management 11(8): 1141-1151.

- Kay C Tan, Pawitra, T (2001) Integrating SERVQUAL and Kano’s model into QFD for service excellence development. Managing Service Quality 11(6): 418-430.

- Yang Ching Chow (2005) The refined Kano’s model and its application. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence 16(10): 1127-1137.