Background

Health misinformation has become a recurrent challenge in the information environment around contemporary health systems rather than an occasional anomaly. Misinformation and disinformation have been used interchangeably. However, the two categories differ in terms of the degree of falseness and intent to harm. Misinformation is unverified, but the source or the spreader is unaware, and the intention is not to harm the public, while disinformation is unauthentic news to mislead the audience, and the source or the spreader knows it is false [1]. However, since this paper is aimed at analyzing and mitigating the negative effects of these rather than their intent, the term misinformation will be used to represent false or misleading information about disease causation, prevention, diagnosis, treatment, and public health policy that is presented as factual and that circulates within communities, media systems, and policy arenas [2-5]. Misinformation around vaccination and other preventive measures, for example, has been linked to reduced uptake and avoidable morbidity [6-9]. At the same time, research on digital information environments documents how online platforms, weakened institutional gatekeeping, and polarized public spheres have created unprecedented opportunities for false and misleading health content to reach large audiences very quickly [10,11].

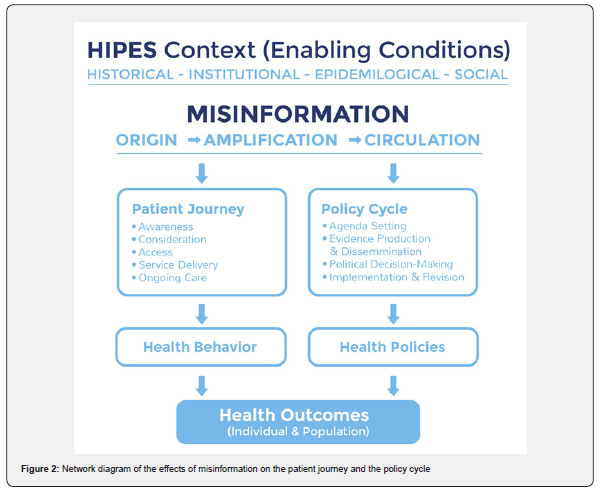

Several frameworks for misinformation have been proposed for different contexts, such as the one with six key domains: sources, drivers, content, dissemination channels, target audiences, and health-related effects of misinformation for studying health misinformation during pandemic contexts [12]. However, the current study treats misinformation as a systemic issue within health systems. Hence, we frame our study of the health-related effects of misinformation to proceed from origin, amplification, to circulation and legitimization, within the enabling conditions, all of which lead to health and policy effects.

Origin of health misinformation

Health-related misinformation can arise through two overlapping pathways.

First, misinformation can emerge “randomly” from fragmented information environments, uncertainty in evolving science, and cognitive biases. People rely on cognitive shortcuts and biases such as confirmation bias, motivated reasoning, and the illusory truth effect to make sense of complex and probabilistic health information. Studies show that exposure to misleading explanations leaves a durable imprint on causal mental models, which often persists even after corrections [6,13,14]. Preliminary findings, anecdotal clinical observations, and low-quality preprints are often translated into simplified and compelling narratives that can be appealing despite being inaccurate. In these information environments, misinformation does not always stem from deliberate fabrication. It frequently emerges from wellintentioned but flawed interpretations of uncertain evidence, gaps in risk communication, and the inherent difficulty of conveying probabilistic or conditional guidance.

Second, health misinformation is strategically created and curated as an exercise of power. Lukes’ third dimension of power emphasizes the capacity of actors to shape perceptions, preferences, and the range of issues that are even perceived as contestable, thereby limiting conflict by structuring what is thinkable [15,16]. Foucault’s concept of knowledge power highlights how regimes of truth are produced through institutions, expertise, and discourses that define what counts as legitimate knowledge and whose experience is recognized [17,18]. In this view, misinformation is not simply incorrect data but a strategic intervention into the production of truth, where economic, ideological, and geopolitical interests actively sponsor, frame, and stabilize particular narratives about risk, responsibility, and appropriate policy responses.

Amplification of health misinformation

Once misinformation exists, its public health significance depends on how it is amplified. Multiple actors have incentives to promote specific health narratives, advocacy coalitions, political actors, and ideological networks that benefit from distrust of scientific or governmental authority. Analyses of “information disorder” emphasize that contemporary misinformation problems arise from the interaction of content, agents (who produce and amplify it), and interpreters (audiences and platforms that filter and react) [19].

Digital platforms and algorithmic curation are central to amplification. Studies of online news diffusion find that false stories reach more people, spread faster, and penetrate deeper through social networks than true stories, in part because novelty and emotional content are prioritized by platform ranking systems and by human sharing behavior [11,20]. Further, the erosion of traditional gatekeepers in journalism and public health communication reduces prepublication filtering, while attention economies reward headlines and narratives that provoke strong emotions [21,22]. In health domains, social media spaces where patients, caregivers, and professionals interact can simultaneously facilitate peer support and create echo chambers in which misleading beliefs about therapies, vaccines, or health systems are repeatedly reinforced [23-25].

Circulation and legitimization

Amplified health misinformation circulates through multiple channels that differ in reach, perceived authority, and audience composition. Opinion leaders such as clinicians, scientists, celebrities, religious authorities, and community leaders function as interpretive filters; when they repeat or fail to challenge misleading claims, they confer legitimacy. In parallel, influencers on social media provide personal testimonies or ideological commentary that integrate misinformation into everyday narratives. Research on social and behavior change communication within socio-ecological models shows that interpersonal networks, community norms, and institutional communication often matter as much as mass media in shaping whether information is accepted, contested, or ignored and eventually circulated [26].

Over time, repetition across channels and from multiple trusted sources can transform contested claims into “common sense”. This process can normalize skepticism toward vaccines, reframe commercial products such as tobacco or ultra-processed foods as matters of personal choice rather than structural risk, or recast public health regulations as infringements on liberty.

Enabling conditions: institutional trust and political context

Origin, amplification, and circulation processes are embedded in broader social and political conditions that shape their effects. HIPES conceptualizes population health trajectories as products of historical, institutional, political, epidemiological, and social processes that interact over long periods [27]. Colonial legacies, dependency relations, and uneven development generate structural vulnerabilities, including underfunded public health institutions, limited surveillance and national data systems, and concentrated media ownership [28,29].

Low institutional trust and perceived corruption reduce the credibility of public health authorities [30,31]. Fragmented or poorly regulated media environments, combined with economic pressures on journalism, can create fertile ground for sensational or conspiratorial content [32,33]. Polarized public spheres transform health issues into identity markers, so that accepting or rejecting health claims signals allegiance to broader political or cultural camps. Finally, low levels of democracy and restricted civic space can both suppress accurate information and enable state or interest group-sponsored misinformation or propaganda, particularly around sensitive topics such as epidemics, environmental exposures, or substance use regulation [34-38].

From structural origins to individual and policy effects

The origin, amplification, and circulation processes described above create specific pathways through which misinformation reaches and affects both individual health decisions and collective policy processes. At the individual level, strategically created misinformation (Lukes’ third dimension of power) shapes the information environment within which patients recognize symptoms, evaluate treatment options, and decide whether to seek or continue care.

Amplification through digital platforms and opinion leaders means that misleading content often reaches patients at critical decision points when searching for health information online, when considering whether to vaccinate a child, or when deciding whether to adhere to chronic disease medication. The enabling conditions described above (low institutional trust, fragmented media, polarized public spheres) determine whether patients interpret this misinformation as credible and actionable.

At the policy level, the same strategic misinformation and amplification mechanisms shape how problems are framed in policy debates, which evidence is considered credible, and which policy options are deemed politically feasible. Interest groups deploy misinformation to influence agenda-setting (defining which health issues warrant policy attention), evidence interpretation (challenging or selectively highlighting research), and political mobilization (framing policies as threats to freedom or economic interests).

In contexts where institutional gatekeepers are weak and commercial interests have substantial political access (HIPES factors), these strategies can effectively delay or weaken healthprotective policies. Crucially, these individual-level and policylevel pathways interact misinformation-influenced patient behaviors shape the political salience of health issues (for example, declining vaccination rates trigger policy debates), while policy responses shape the information environments in which patients make decisions (for example, advertising regulations affect commercial messaging).

In sum, health misinformation deserves systematic study because it sits at the intersection of patient experience, health policy processes, both affecting health outcomes. This study systematically traces these interconnected pathways and aims to understand how misinformation affects the patient journey and health policies. This is key for explaining its effects on the individual and population health outcomes, and for designing strategies that manage, rather than unrealistically attempt to eradicate, its influence.

Methods

This paper is a theory-driven, conceptually oriented analysis that synthesizes existing empirical and theoretical literature on health misinformation, health behavior, patient experience, and population health policy. It does not report new primary data.

It uses HIPES as the macro contextual framework that explains why the effects of misinformation vary across settings and populations. While the patient journey [39,40], theories of health behavior [41-43], and health policy cycle frameworks [40] specify how misinformation influences individual decision making and policy processes. HIPES identifies the enabling conditions that shape the magnitude, direction, and persistence of these effects, including features of the information environment, institutional trust, and structural vulnerabilities. In this way, HIPES provides the contextual layer needed to interpret heterogeneity in misinformation impacts, complementing the process-oriented insights generated by the patient journey and policy cycle analyses.

Patient journey model

To structure the patient journey, the paper uses the Qualtrics

five-stage patient journey model, which conceptualizes it as the

sequence of events from initial recognition of a need for care to

ongoing engagement after treatment. It was chosen over other

models for being disease-agnostic. The stages are:

1. Awareness where individuals recognize symptoms or

health needs and begin to search for options.

2. Consideration where they compare providers or

interventions, weigh perceived benefits, risks, and costs, and form

preferences.

3. Access where they attempt to obtain appointments,

navigate insurance or payment arrangements, and overcome

logistical barriers.

4. Service delivery where clinical care is provided,

including interactions with providers, diagnostics, and treatment.

5. Ongoing care where individuals engage in follow-up,

self-management, rehabilitation, or chronic care maintenance.

Please note that the health outcome of stages 3, 4, and 5 will also be affected by external and structural factors of the health system, such as infrastructure and service delivery attributes. However, this paper focuses only on the effects caused by misinformation on these stages via health behavior or healthseeking behavior. Further, in the awareness stage, in addition to being able to recognize symptoms or health needs, the effect of misinformation on healthy lifestyle and awareness on preventing disease risk factors was assessed.

The analysis maps how misinformation can influence these stages based on a structured review of the literature. For example, misleading information about disease severity or treatment efficacy might shape risk perception and might deter access.

Behavioral theories of health decision making

To explain how information affects behavior at each stage of

the patient journey, the paper draws on a set of complementary

health behavior theories.

• Health Belief Model (HBM) conceptualizes health

behavior as a function of perceived susceptibility, perceived

severity, perceived benefits, perceived barriers, cues to action, and

self-efficacy. Within this model, misinformation is treated as a key

determinant of these perceptions.

• Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA), Theory of

Planned Behavior (TPB), and the Integrated Behavioral

Model (IBM) view behavior as driven by intention, which in turn

is shaped by attitudes, perceived norms, and perceived behavioral

control. Information and misinformation are modeled as inputs

into beliefs about outcomes, normative expectations, and control,

thereby influencing intentions to, for example, vaccinate, seek

care, adhere to treatment, or engage in risk behaviors [42].

• Transtheoretical Model (TTM) situates individuals

along stages of change (precontemplation, contemplation,

preparation, action, maintenance) and emphasizes stage-specific

processes and decisional balance. Misinformation is conceptualized

as affecting which stage people occupy and how they progress,

for example, by reinforcing ambivalence, undermining perceived

benefits of change, or providing rationalizations that prevent or

support movement from contemplation to action [43].

• Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) stresses reciprocal

determinism between behavior, personal factors, and

environment, focusing on constructs such as self-efficacy,

outcome expectations, observational learning, and reinforcement.

Misinformation is analyzed as shaping outcome expectancies (for

example, overstating the benefits of unproven therapies) and

influencing perceived self-efficacy [44].

• Socio-ecological communication models extend the

focus from individuals to networks, communities, institutions,

and broader social systems, emphasizing embeddedness. These

models are used to interpret how interpersonal communication,

community norms, mass media, and digital platforms jointly

shape exposure to and interpretation of misinformation [41].

Together, these theories guide the specification of pathways from misinformation to beliefs, intentions, and behaviors at each stage of the patient journey and help identify recommendations where different types of interventions (information correction, norm change, structural change) may be most effective.

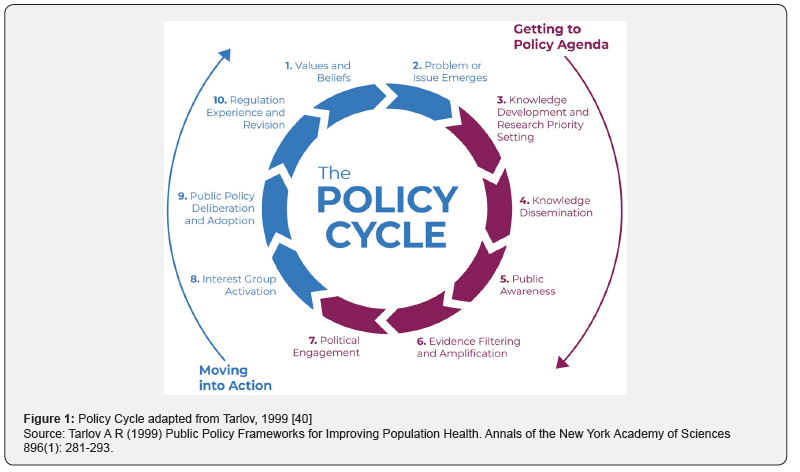

Policy cycle framework

The paper uses Tarlov’s public policy development process as

the basis for assessing the effects of misinformation on various

stages of the health policy cycle. For analytical clarity, we group

Tarlov’s ten policy cycle stages (Figure 1) into four main phases

that capture the essential dynamics of policy development:

1. Agenda-Setting (stages 1-2: values/beliefs and problem

emergence)

2. Evidence Production & Dissemination (stages 3-6:

knowledge development, dissemination, public awareness, and

evidence filtering)

3. Political Decision-Making (stages 7-9: political

engagement, interest group activation, and deliberation/

adoption)

4. Implementation & Revision (stage 10: regulation

experience and revision)

For each stage, the analysis examines:

• How misinformation and strategic communication can

redefine values, reframe issues, or obscure certain problems.

• How misinformation can shape what counts as relevant

knowledge, which research is funded, and how evidence is

synthesized and communicated.

• How media and platform infrastructures filter and

amplify information during agenda setting and political

mobilization.

• How organized interests deploy misinformation to

influence legislative and regulatory outcomes.

• How policy implementation experiences feed back into

the information environment, potentially creating new cycles of

misinformation.

Analytical synthesis

It involves the construction of conceptual network style

models that integrate insights from HIPES, the patient journey

framework, behavioral theories, and the policy cycle. The findings

are synthesized in three steps:

1. Effects of misinformation on the patient journey stages

2. Effects of misinformation on the policy cycle

3. The combined effects and the interaction of the above on

individual and population health outcomes

These findings are presented in the next section and then form the basis of the recommendations section, which focuses on practical options for various stakeholders seeking to manage the negative effects of misinformation on health outcomes.

Findings

Across the five patient journey stages, several consistent patterns emerge. Structured reviews of infodemics and health misinformation show that misleading content reduces willingness to seek appropriate healthcare, vaccinate, obstructs outbreak control, interrupts access to care, heightens fear and psychological distress, and contributes to misallocation of resources [4,7,9,45,46]. These effects can be understood through the behavioral theories outlined in the Methods section, which describe how information shapes perceived risk, expected outcomes, social norms, and self-efficacy [26,42-44]. The patterns below summarize how misinformation affects each stage of the patient journey.

Effects of misinformation on the patient journey stages Awareness

In the awareness stage, misinformation shapes whether individuals recognize a condition as serious, urgent, or even “real” and whether they perceive themselves as at risk. Systematic reviews of social media health misinformation document high volumes of misleading content on vaccines, cancer, noncommunicable diseases (NCDs), mental health, and infectious diseases such as COVID-19 and measles, with false claims often more engaging than accurate content [4,8,10,23,24,45]. Within the Health Belief Model, this information environment alters perceived susceptibility and severity by normalizing narratives such as “this infection is mild for most people,” “antibiotics cure colds,” or “cancer is always a death sentence,” which can either blunt or exaggerate perceived risk and hence the response [6,13,14,44,46].

At the same time, misinformation often provides simple causal stories (for example, attributing disease purely to lifestyle, stress, or conspiracy) that compete with more complex biomedical explanations. These narratives influence how symptoms are interpreted and whether they are linked to modifiable risk factors or to structural determinants. In Transtheoretical Model terms, misleading reassurance or fatalistic narratives can keep people in the precontemplation stage, especially for behaviors related to tobacco, alcohol, diet, and physical activity [8,24,43,47].

Consideration

In the consideration stage, patients actively weigh options and form preferences about providers, facilities, and treatments. Here, misinformation alters both attitudes toward evidence-based options and expectations about unproven alternatives. Studies of online cancer information show that a substantial share of widely accessed content comprises inaccurate or incomplete information, including promotion of unproven therapies, miracle cures, or extreme diets, with many items judged as potentially harmful by clinical experts [48]. Similar patterns are observed for vaccines and NCDs, where content exaggerating rare adverse events or questioning efficacy can shift attitudes against recommended interventions [4,7-9,46]. This is supported by a popular concept from consumer behavior research called the negativity bias. For example, patients disproportionately weigh misinformation about potential adverse effects over treatment benefits when making decisions. It explains why fear of vaccine side effects, although rare and sometimes false, leads to hesitancy despite the vaccine’s many proven benefits [49].

Within the Theory of Planned Behavior and the Integrated Behavioral Model, these messages modify beliefs about outcomes (“chemotherapy does more harm than good”), social norms (“most people I know do not vaccinate”), and control (“there is nothing I can do about my risk”), thereby weakening intentions to seek or accept beneficial care [42,44]. For mental health, stigma-laden misinformation about psychiatric diagnoses and psychotropic medications can lower perceived benefits and intensify perceived barriers to seeking help, contributing to delayed or foregone care [50,51].

Access

At the access stage, misinformation interacts with structural barriers such as availability, physical and financial access, and quality of health services to shape the health outcomes. Reviews of infodemics and COVID-19 misinformation show that false narratives have led some populations to physically interrupt access to care, deeming it unsafe, and delay seeking help for both acute and chronic conditions [4,7,19, 46,52-54].

Misinformation also contributes to inappropriate access patterns. In the case of antibiotics and antimicrobial resistance, persistent misconceptions that antibiotics are effective against viral infections or necessary for rapid recovery drive inappropriate demands for prescriptions and over-the-counter acquisition. This pattern is well-documented across regions and persists despite public awareness campaigns, contributing to antimicrobial resistance and avoidable side effects [55-59]. In behavioral terms, such beliefs increase perceived benefits and reduce perceived barriers for unnecessary antibiotic use.

Service Delivery

Within service delivery, misinformation reshapes the content and quality of clinical encounters. Clinicians increasingly report that patients arrive with pre-formed beliefs based on online searches and social media content, which can both enrich and complicate shared decision making [60,61]. When patients hold strong misinformed beliefs about diagnosis, prognosis, or treatment, consultations may involve substantial time spent on myth correction and negotiation, which can lengthen visits and add to provider workload [64-66].

In oncologic and NCD care, misleading information can result in patients insisting on ineffective or harmful treatments, refusing indicated therapies, or demanding unnecessary tests, straining relationships with providers [65-68]. For mental health and substance use, conspiracy narratives can lead patients to reject medications, psychotherapy, or harm reduction services. Within SCT and socio-ecological models, these dynamics reflect the influence of peer networks and online communities that provide reinforcement and identity around particular narratives, making it harder for clinicians to shift beliefs within a single encounter [41,44]. In settings with constrained resources, such dynamics can reduce effective coverage by diverting time and attention away from other patients and undermining guideline-consistent care.

Ongoing Care

In the ongoing care stage, misinformation affects adherence, self-management, and long-term engagement with health services, which are especially relevant for NCDs. Systematic reviews and empirical studies show that exposure to health misinformation is associated with lower adherence to recommended preventive behaviors, reduced uptake of boosters or follow-up doses, and substitution of evidence-based therapies with unproven alternatives [4,46,69]. In cancer care, for example, misinformed beliefs about recurrence risk, dietary cures, or the dangers of adjuvant therapy can lead some patients to discontinue treatment prematurely or to delay surveillance [66,70-74].

For NCDs, misinformation about medications such as statins, antihypertensives, or insulin can erode trust and lead to discontinuation, especially when side effects are interpreted through narratives encountered online [75-79]. Across conditions, these patterns align with TTM constructs, in which misinformation can trigger regression from maintenance back to earlier stages or reinforce relapse by reframing adherence as harmful or unnecessary [43,47]. At the population level, such dynamics diminish the effectiveness of health systems.

Overall, the stage-specific findings indicate that misinformation acts through well-described cognitive, social, and structural mechanisms at each point of the patient journey. Information is not merely a backdrop but a dynamic determinant of how individuals perceive risk, navigate options, engage with providers, and sustain care, operating alongside constraints such as cost, accessibility, and service quality.

Effects of misinformation on health policies

Using Tarlov’s policy cycle, misinformation can be seen as influencing each stage at which problems are constructed, evidence is produced and interpreted, and policies are debated, adopted, and revised [40]. While several other factors influence each stage of the policy cycle, this study focuses on misinformation as a cross-cutting factor.

While the specific actors and channels differ across domains such as tobacco, alcohol, NCD prevention, AMR, and mental health, several recurrent mechanisms emerge, which are discussed across the policy cycle stages.

Agenda-Setting

• Misinformation shapes what counts as a health problem

and who is held responsible, influencing baseline assumptions

about causation and appropriate intervention.

• It affects which issues rise on the agenda by making

some risks seem exaggerated, fabricated, or trivial, which can

delay recognition of emerging threats and reduce perceived

urgency.

• It also increases contestation around problem

definitions, turning empirical questions (severity, prevalence,

preventability) into identity or worldview disputes, which can

slow early policy momentum.

Evidence Production & Dissemination [80-84]

• During evidence production, misinformation interacts

with power and incentives to shape what research gets funded

and asked, potentially privileging narratives that emphasize, for

example, individual responsibility or voluntary approaches while

sidelining structural policy options.

• During dissemination, misinformation competes with

and distorts scientific findings, including through selective

quotation, oversimplification, or misrepresentation, with both

digital platforms and traditional media sometimes amplifying

misleading frames.

• Misinformation influences public awareness, risk

perception, and salience, generating intense but misdirected

concern about rare harms due to negativity bias while muting

concern about more prevalent risks and population-level impacts

such as outbreak possibility, alcohol related cancers, or antibiotic

resistance.

• These patterns influence how the public perceives

proposed policies. Measures such as sugar taxes, marketing

restrictions, or smoke-free environments may be portrayed as

attacks on personal freedom or small businesses rather than as

public health interventions, affecting both support and opposition.

• Interest groups can do evidence filtering and

amplification strategically to highlight, downplay, or curate

evidence to support preferred positions, often creating

asymmetric visibility where well-resourced groups can amplify

supportive studies more effectively than public-interest actors

can correct or contextualize them.

Political Decision-Making

• Misinformation shapes political engagement by

providing mobilizing frames that influence how constituencies

interpret proposed policies, increasing polarization and lowering

the perceived legitimacy of certain interventions or institutions.

• It supports organized actor strategies by enabling

selective evidence to use, targeted narratives, and coalition

messaging that can shift the perceived costs, benefits, and fairness

of regulatory options.

• In formal deliberation and adoption processes,

misinformation can alter how policy options are framed, how

evidence is interpreted, and which voices are treated as credible,

influencing hearings, testimony, submissions, and advisory

discussions.

Implementation & Revision

• Misinformation shapes implementation by influencing

how policies are understood, complied with, and judged, including

by promoting anecdotal or short-term interpretations that conflict

with longer-term health outcome expectations.

• It can distort evaluation by emphasizing claimed failures

or unintended consequences while downplaying benefits, and by

misrepresenting early data to justify rollbacks, weakening, or

non-enforcement.

• The result is a feedback loop where contested narratives

about implementation outcomes re-enter agenda-setting and

evidence debates, sustaining misinformation as a persistent

feature of policy experience.

In summary, across the stages of the policy cycle, misinformation acts as a cross-cutting mechanism that aligns with existing power structures to shape which problems are recognized, what evidence is accepted, which policies are considered feasible, and how their impacts are interpreted.

The combined effects of the above on individual and population health outcomes

Bringing together the patient journey and policy cycle perspectives, the analysis indicates that misinformation affects health outcomes through multiple converging and mutually reinforcing pathways. Figure 2 conceptualizes these pathways as interconnected layers operating within the historical, institutional, political, epidemiologic, and social structural context captured by HIPES.

At the individual and interpersonal level, misinformation shapes beliefs, emotions, and behaviors across the patient journey, resulting in patterns such as delayed presentation, refusal of effective prevention or treatment, inappropriate demand for ineffective or harmful interventions, and reduced adherence to long-term therapies. These patient-level effects translate into increased incidence and severity of preventable conditions, higher complication rates, and avoidable deaths in domains including NCDs, cancer, infectious diseases, mental health, and AMR.

At the meso and macro levels, misinformation interacts with policy processes to influence resource allocation, regulatory strength, and the design of health system responses. Where certain narratives and politicized misinformation succeed in weakening regulations on tobacco, alcohol, unhealthy food, or inappropriate antibiotic use, population exposure to risk factors remains high, and structural drivers of disease are left unaddressed. Policy distortions can also exacerbate inequities when benefits of protective interventions accrue mainly to groups with higher health literacy and access, while harms of weak regulation fall disproportionately on socioeconomically disadvantaged communities.

Crucially, the patient journey and policy pathways are not independent. Policies shape the information environment in which patients make decisions, for instance, through the regulation of advertising and labeling, investment in public health communication, or platform governance. In turn, aggregated patient behaviors influence epidemiologic patterns, media narratives, and political salience, feeding back into the policy cycle.

This can generate amplification loops, such as:

• Misinformation undermines vaccine uptake,

contributing to outbreaks, which then fuel further fear, distrust,

and conspiratorial narratives.

• Interest groups led to misinformation weakening alcohol

or tobacco control policies, sustaining high levels of consumption

and harm, which in turn are framed as evidence that individual

responsibility approaches are sufficient.

• Misconceptions about antibiotics are driving

inappropriate use, accelerating AMR, and prompting narratives

that blame prescribers or patients while obscuring structural

policy drivers.

These loops are conditioned by deeper historical and institutional factors, including colonial legacies, market structures, and the strength of democratic institutions and civil society. The combined effect is a set of patterned vulnerabilities in which certain populations and conditions are repeatedly exposed to information and policy environments that make suboptimal or harmful outcomes more likely.

Overall, the findings indicate that misinformation should not be conceptualized as a series of isolated falsehoods but as a system-level phenomenon that reconfigures patient journeys and health policies in ways that degrade individual and population health outcomes. These dynamics imply that responses focused solely on fact-checking or individual media literacy will be insufficient. The subsequent Recommendations section, therefore, focuses on actions that stakeholders across the health ecosystem can take to manage, rather than eliminate, the health impacts of misinformation by intervening at multiple points along these interconnected pathways.

Recommendations

1. Reconfiguring the Patient Journey to Address Misinformation

1.1 Patient Navigation Systems with Verified Information Integration

• Adopt patient navigation as a standard of care that

integrates both care pathways and verified information sources at

every stage of the health journey.

• Ministries of Health mandate that all public health

facilities provide standardized navigation materials (printed and

digital) that include both care access instructions for all stages of

the patient journey and a repository of verified information with

sources available in regulated channels containing comprehensive

information for common health conditions, which is progressively

expanded to include more and more topics.

o Add light-touch “accuracy prompts” (for example: “Take

a moment to check accuracy before sharing”) within patient

portals, appointment reminders, and navigation chat tools at the

point of forwarding or reposting health information [85]

o Add pre-exposure “misinformation warnings” (brief

forewarnings that misleading claims may be encountered about

a topic) [86]

1.2 Health System Monitoring of Misinformation Impact

• Integrate misinformation exposure and impact

(including at least one health-relevant outcome) as standard

indicators in health surveillance and data collection systems,

treating it as a social determinant of health.

• Add 3-5 standardized questions about information

sources and health beliefs to existing patient intake forms,

representative national health surveys, and disease surveillance

protocols, with data aggregated quarterly for policy review.

1.3 Disclosure Requirements for Health Information in

Regulated Channels

• Require disclosure of sources, qualifications, and

conflicts of interest for health information disseminated through

regulated channels: clinical settings, paid advertising, professional

publications, government reports and websites, and monetized

digital content.

• Enforce digital watermarking as a legally enforceable

safeguard against misinformation. This would include the

disclosure of whether the content is AI-generated or modified,

as well as key metadata such as country of origin, institutional

source, or third-party affiliation [87].

• Establish disclosure standards through existing

regulatory bodies (medical boards, advertising authorities,

media regulators) with graduated enforcement: warnings for

first violations, fines for repeat offenses, and suspension of

professional privileges or advertising rights for systematic noncompliance.

• Upon enforcement, regulated channels could act as the

‘go-to’ sources of reliable information.

1.4 Platform Accountability Strategies Based on Country Context

• Adopt platform engagement strategies matched to

country leverage: voluntary cooperation for small/medium

countries, regional coordination for collective bargaining power,

and direct regulation only for large economies with market power.

Where feasible, encourage or require platforms to deploy and

evaluate warning labels and informational overlays on posts with

high-momentum health claims [85].

o Small/medium countries (most countries): Establish

formal partnerships with platforms requesting health authority

designation, fast-track content review, and participation in

fact-checking programs, while simultaneously joining regional

coalitions to build future collective negotiating power.

o Regional blocs: Coordinate platform standards and

enforcement across member states to increase leverage through

market size.

o Large economies (EU, US, China, India, Brazil):

Enact binding regulation requiring algorithmic transparency,

prioritization of verified health sources, and significant fines for

non-compliance

1.5 Health and Information Literacy as Public Health Priority

• Institutionalize health and information literacy as

core components of both health service delivery and education

systems, with population-level health literacy as a health system

performance indicator.

• Ministries of Health and Education jointly develop

national health literacy standards, mandate curriculum integration

starting with pilot schools, require literacy assessment in clinical

quality metrics, and measure population literacy through annual

national health surveys.

• Health Literacy can be measured in all first encounters

with providers to assess the risk of low health literacy – using

available tools such as the Test of Functional Health Literacy in

Adults (TOFHLA) [88].

• Include brief media literacy tips (for example, “pause,

check source, check date, check independent confirmation”) in

patient-facing materials [85].

2. Reconfiguring the Policy Cycle to Address Misinformation

2.1 Patient Participation as Policy Development Standard

• Mandate meaningful patient and community

participation as a requirement for all stages of health policy

development, from agenda-setting through evaluation.

• Enact legislation requiring: a minimum percentage of

patient representatives on policy committees, mandatory public

consultation periods before policy adoption, a dedicated budget

for patient organization participation, and annual reporting on

participation quality and diversity.

2.2 Mandatory Comprehensive Evidence Review for Policy Decisions

• Require that all major health policy decisions be based

on systematic reviews of all available evidence, and where

comprehensive reviews don’t exist, commission independent

peer review before decisions are made.

• Establish policy standards requiring: (1) All policy

proposals must cite existing systematic reviews from recognized

sources (Cochrane, WHO, established HTA agencies), (2) When

systematic reviews don’t exist, appoint independent expert

panels to review all available evidence, (3) Publish all evidence

considered in policy decisions, (4) Require public justification

with documented rationale if policymakers deviate from

systematic review conclusions.

2.3 Transparency as Policy Development Principle

• Establish comprehensive transparency as a foundational

principle of policy development, requiring public disclosure of all

actors, interests, and evidence informing health policy decisions.

• Create public online registries (maintained by the health

ministry or independent agency) where all policy consultation

participants, meeting records, disclosed conflicts of interest,

and evidence documents are published within 30 days of policy

meetings, with search functionality and plain language summaries

for citizen and journalist access [89].

2.4 Integrated Misinformation Monitoring and Independent Verification System

• Create a Health Information Integrity Council:

Establish an independent statutory or charter-based body with

a protected mandate to assess information integrity in regulated

channels (Recommendation 1.3). Independence safeguards

should include fixed-term appointments for leadership,

transparent selection criteria, public disclosure of conflicts of

interest, an explicit prohibition on disputed funding, ring-fenced

multi-year public financing, and publication of meeting minutes,

methods, and decisions.

• Define what “verification” means and what it is

verified against: Require the Council to use a public “benchmark

hierarchy” for adjudication, specifying that claims are assessed

against: (1) up-to-date national clinical and public health guidance,

(2) WHO and other recognized international normative guidance,

(3) systematic reviews and other peer reviewed evidence, and

(4) regulated product information such as approved labels,

safety communications, and pharmacovigilance alerts. Where

evidence is uncertain or evolving, outputs should explicitly label

conclusions as “supported”, “inconclusive”, or “not supported”,

and state what evidence would change the rating.

• Clarify the regulated channels under monitoring:

Specify the set of channels the monitoring function covers, such

as official Ministry of Health communications, public health

agency messaging, etc. Require a public registry of these channels,

including points of contact and update responsibilities.

• Make patient empowerment a core operating

principle: Ensure patients and patient groups have formal voting

representation and agenda-setting capacity. Provide simple

reporting tools in multiple languages and low-bandwidth formats

and create feedback loops that track whether corrections were

made.

• Build accountability and learning into the system:

Publish periodic impact and process metrics (timeliness, reach,

correction uptake, recurring claim themes), conduct independent

audits, and establish clear legal and administrative consequences

for repeated dissemination of demonstrably misleading claims

within regulated channels, while protecting legitimate scientific

debate through transparent criteria and due process.

2.5 Cross-Sectoral Coordination as Governance Model

• Adopt whole-of-government and whole-of-society

coordination as the governance model for responding to health

misinformation, replacing siloed approaches.

• Establish a standing inter-ministerial committee (health,

education, communications) meeting quarterly, create a multistakeholder

advisory body including civil society and private

sector, develop shared response protocols, and conduct annual

coordination exercises to maintain readiness.

2.6 Professional Accountability with Strong Safeguards

• Establish professional accountability standards through

licensing and regulatory bodies for health professionals who

spread misinformation, with graduated sanctions and robust due

process protections.

• Medical, nursing, and pharmacy associations update

professional codes to prohibit spreading health misinformation,

establish clear disciplinary procedures to protect legitimate

scientific debate through independent review panels, and publish

decisions transparently.

Cross-Cutting Enablers Enabler 1: Legal and Regulatory Frameworks

• Enact enabling legislation that provides a legal basis

for health information governance while protecting freedom of

expression, scientific inquiry, and democratic participation.

• Draft and pass legislation establishing statutory

authority for health information monitoring, enforcement powers

for disclosure requirements, protection for whistleblowers,

remedies for harmed parties, explicit exclusions for scientific

uncertainty and good-faith debate, and sunset clauses requiring

periodic review.

Enabler 2: Sustained Funding as Core Function

• Recognize misinformation prevention and response as a

core public health function requiring dedicated, sustained budget

allocation rather than emergency-only funding.

• Create dedicated budget line items in health ministry

budgets labeled “health information integrity” or “infodemic

management,” protected through multi-year appropriations, with

funding levels tied to documented population impact and reviewed

annually based on monitoring data from Recommendation 1.2.

Enabler 3: Institutionalize infodemic management as a standing function (not crisis-only)

• Routine social media scanning, rapid synthesis, daily and weekly reports, community engagement, and resilience-building at the national level aligned with WHO’s guidance [90-93].

Lastly, AI and data interoperability, privacy, and safety policies contain a set of “governance design patterns” that can be adapted to manage misinformation.

• Common schemas for misinformation monitoring

and response: define interoperable data fields for health

misinformation events (claim type, topic, language, geography,

format, engagement trajectory, exposure proxies, and response

actions), so health authorities, platforms, and researchers can

compare misinformation trends across health systems and time.

• Privacy-preserving social listening: default to aggregate

signals, topic-level trend analysis, and privacy-preserving

evaluation where possible, rather than individual-level profiling,

aligning “misinformation surveillance” with data minimization

norms.

• Purpose limitation for misinformation data sharing:

specify permitted uses (for example, risk assessment, evaluation

of interventions, and service-navigation support) and prohibit

repurposing for unrelated enforcement or commercial targeting.

These recommendations are intended to manage health misinformation rather than to eliminate it. This study acknowledges that efforts to “counter” misinformation inevitably raise a circular challenge: doing so depends on access to accurate information and on processes or institutions that can adjudicate credibility, yet those same processes are themselves vulnerable to uncertainty, incomplete evidence, cognitive and institutional biases, and the influence of vested interests. Accordingly, the recommendations should be read as governance and practice principles that strengthen how health systems and information environments handle contested claims under real-world constraints in efforts to mitigate the negative effects of misinformation on health outcomes. They are designed to be broadly applicable across geographies, income levels, and disease areas; however, their effectiveness is contingent on implementation capacity and on enabling conditions in the surrounding context, including the level of democracy and civic space, the power relations of interest groups, institutional checks and accountability, prevalence of corruption, and the degree of media independence or control. In settings where these contextual conditions need improvement, priority may need to shift toward institutional safeguards, transparency mechanisms, and protections for independent evidence generation and dissemination as prerequisites for sustained impact.

Conclusion

This analysis demonstrates that health misinformation operates as a system-level phenomenon that fundamentally reconfigures both individual patient journeys and collective policy processes, with cascading effects on health outcomes. The integration of HIPES as a contextual framework with patient journey and policy cycle models reveals that misinformation does not simply introduce isolated errors into decision-making. Rather, it systematically alters risk perception at the awareness stage, distorts option evaluation during consideration, interrupts appropriate access patterns, complicates clinical encounters during service delivery, and undermines long-term adherence in ongoing care. Simultaneously, across the policy cycle, misinformation shapes which health problems are recognized as urgent, influences what evidence is considered credible, determines which policy options are deemed politically feasible, and distorts how implementation outcomes are interpreted. These patient-level and policy-level pathways interact through amplification loops, where weakened policies sustain information environments that make suboptimal health behaviors more likely, while aggregated patient behaviors feed back into political debates and policy revision.

The recommendations presented reflect this systemic understanding by targeting multiple intervention points rather than relying on single-strategy approaches. Reconfiguring patient navigation to integrate verified information, establishing transparent evidence review processes for policy decisions, creating independent monitoring systems with strong safeguards against censorship, and building cross-sectoral coordination represent complementary strategies that address different leverage points within the larger system. Critically, these recommendations recognize that eradicating misinformation is neither feasible nor necessarily desirable in democratic societies that value open debate. Instead, the goal is to manage misinformation’s influence by strengthening the information environments within which patients make decisions and policies are developed, while preserving space for legitimate scientific uncertainty, good-faith disagreement, and democratic participation.

Future research could examine how specific interventions perform across diverse political and institutional contexts, assess whether addressing misinformation at multiple points produces synergistic effects, and evaluate whether strengthened information governance can reduce health inequities or inadvertently worsen them by benefiting populations with greater resources and literacy. Understanding misinformation as embedded within broader health system dynamics, rather than as an external threat, provides a foundation for developing responses that are both more effective and more compatible with democratic values.

References

- Rastogi S, Bansal D (2022) A review on fake news detection 3T’s: typology, time of detection, taxonomies. International Journal of Information Security 22(1): 177-212.

- Kirk J (2024) Infodemic, Ignorance, or Imagination? The Problem of Misinformation in Health Emergencies. International Political Sociology 18(4): 1-18.

- Rubinelli S, Purnat TD, Wihelm E, Traicoff D, Namageyo Funa A, et al. (2022) WHO competency framework for health authorities and institutions to manage infodemics: its development and features. Human Resources for Health 20(1): 1-14.

- Kbaier D, Kane A, McJury M, Kenny I (2024) Prevalence of Health Misinformation on Social Media Challenges and Mitigation Before, During, and Beyond the COVID-19 Pandemic: Scoping Literature Review. Journal of Medical Internet Research 26: 1-16.

- World Health organization. Infodemic. (n.d.). Retrieved December 11, 2025.

- Lewandowsky S, Ecker UKH, Seifert CM, Schwarz N, Cook J (2012) Misinformation and Its Correction: Continued Influence and Successful Debiasing. Psychological Science in the Public Interest 13(3): 163-198.

- Kisa S, Kisa A (2024) A Comprehensive Analysis of COVID-19 Misinformation, Public Health Impacts, and Communication Strategies: Scoping Review. Journal of Medical Internet Research 26(1): 1-19.

- Parums DV (2024) A Review of the Resurgence of Measles, a Vaccine-Preventable Disease, as Current Concerns Contrast with Past Hopes for Measles Elimination. Medical Science Monitor 30.

- Allen J, Watts DJ, Rand DG (2024) Quantifying the impact of misinformation and vaccine-skeptical content on Facebook. Science 384(6699).

- Lazer DMJ, Baum MA, Benkler Y, Berinsky AJ, Greenhill KM, et al. (2018) The science of fake news: Addressing fake news requires a multidisciplinary effort. Science 359(6380): 1094-1096.

- Vosoughi S, Roy D, Aral S (2018) The spread of true and false news online. Science 359(6380): 1146-1151.

- Alvarez Galvez J, Carretero Bravo J, Lagares Franco C, Ramos Fiol B, Ortega Martin E (2025) Development of a Conceptual Framework of Health Misinformation During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Systematic Review of Reviews. JMIR Public Health and Surveillance 11: 1-20.

- Susmann MW, Wegener DT (2021) The role of discomfort in the continued influence effect of misinformation. Memory & Cognition 50(2): 435-448.

- McIlhiney P, Gignac GE, Ecker UKH, Kennedy BL, Weinborn M (2023) Executive function and the continued influence of misinformation: A latent-variable analysis. PLOS ONE 18(4): 1-21.

- Dimensions of power Developing Organizational and Managerial Wisdom 2nd Edition. (n.d.). Retrieved December 11, 2025.

- Dowding K (2006) Three-dimensional power: A discussion of Steven Lukes’ power: A radical view. Political Studies Review 4(2): 136-145.

- Anderson DE (2021) Power and Regimes of Truth. Metasemantics and Intersectionality in the Misinformation Age Pp: 133-182.

- Power/Knowledge by Michel Foucault. Research Starters. EBSCO Research. (n.d.). Retrieved December 11, 2025.

- Claire Wardle, Hossein Derakhshan (2017) Information disorder: Toward an interdisciplinary framework for research and policy making (n.d.). Retrieved December 11, 2025.

- Humans, not bots, are to blame for spreading false news on Twitter. WIRED. (n.d.). Retrieved December 11, 2025.

- Information Gatekeepers Decline. Area. Sustainability. (n.d.). Retrieved December 11, 2025.

- The End of the Traditional Gatekeeper. Gnovis Journal. Georgetown University. (n.d.). Retrieved December 11, 2025.

- Laranjo L (2016) Social Media and Health Behavior Change. Participatory Health through Social Media Pp: 83-111.

- Denniss E, Lindberg R (2025) social media and the spread of misinformation: infectious and a threat to public health. Health Promotion International 40(2): 1-10.

- Yin JDC, Wu TC, Chen CY, Lin F, Wang X (2025) The Role of Influencers and Echo Chambers in the Diffusion of Vaccine Misinformation: Opinion Mining in a Taiwanese Online Community. JMIR Infodemiology 5(1): 1-14.

- D Lawrence Kincaid, Maria Elena Figueroa, Doug Storey, and Carol Underwood. A Socio-Ecological Model of Communication for Social and Behavioral Change. Breakthrough ACTION and RESEARCH (n.d.). Retrieved December 11, 2025.

- Gonzalez AR (2025) Colonialism, Dependency, and Health Trajectories: An Integrative Analysis of Historical Trends, Epidemiology, and Policy Analysis in Puerto Rico between 1898-1969. Juniper Online Journal of Public Health 10(2): 1-12.

- Colonial Healthcare Legacies. (n.d.). Retrieved December 12, 2025.

- Miller M, Toffolutti V, Reeves A (2018) The enduring influence of institutions on universal health coverage: An empirical investigation of 62 former colonies. World Development 111: 270-287.

- Huang YHC, Cai Q, Wang X, Sun J (2025) What drives public support for health policies? The protection-motivated mediating model of institutional trust and risk paradox. Social Science & Medicine 383: 1-12.

- Glynn EH (2022) Corruption in the health sector: A problem in need of a systems-thinking approach. Frontiers in Public Health 10: 1-15.

- Zenone M, Kenworthy N, Maani N (2022) The Social Media Industry as a Commercial Determinant of Health. (n.d.). Retrieved December 12, 2025. International Journal of Health Policy and Management 12(1): 1-4.

- Rachael Kent (2025) When Health Misinformation Kills: social media, Visibility, and the Crisis of Regulation. Feature from King’s College London. (n.d.). Retrieved December 12, 2025

- Bethke FS, Wolff J (2023) Lockdown of expression: civic space restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic as a response to mass protests. Democratization 30(6): 1073-1091.

- Vasist PN, Chatterjee D, Krishnan S (2023) The Polarizing Impact of Political Disinformation and Hate Speech: A Cross-country Configural Narrative. Information Systems Frontiers 26(2): 663-688.

- Donald C Hellmann (2023) Task Force Disputable Content and Democracy: Freedom of Expression in the Digital World Pp: 1-170.

- Edgell AB, Lachapelle J, Lührmann A, Maerz SF (2021) Pandemic backsliding: Violations of democratic standards during Covid-19. Social Science & Medicine 285: 1-10.

- Breuer A (n.d.) (2025) From polarization to autocratisation: the role of information pollution in Brazil’s democratic erosion Pp: 1-55.

- Your Complete Guide to Patient Journey Mapping-Qualtrics. (n.d.). Retrieved December 9, 2025.

- Tarlov AR (1999) Public policy frameworks for improving population health. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 896: 281-293.

- A Socio-Ecological Model of Communication for Social and Behavioral Change (n.d.). Retrieved December 9, 2025.

- Theory of reasoned action, theory of planned behavior, and the integrated behavioral model (n.d.). Retrieved December 9, 2025.

- Prochaska JO, Velicer WF (1997) The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. American Journal of Health Promotion 12(1): 38-48.

- Bandura A (2004) Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Education & Behavior 31(2): 143-164.

- Suarez Lledo V, Alvarez Galvez J (2021) Prevalence of Health Misinformation on Social Media: Systematic Review. Journal of Medical Internet Research 23(1): 1-17.

- Do Nascimento IJB, Pizarro AB, Almeida JM, Azzopardi-Muscat N, Gonçalves MA, et al. (2022) Infodemics and health misinformation: a systematic review of reviews. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 100(9): 544-561.

- Petticrew M, van Schalkwyk MC, Knai C (2025) Alcohol industry conflicts of interest: The pollution pathway from misinformation to alcohol harms. Future Healthcare Journal 12(2): 1-6.

- Teplinsky E, Ponce SB, Drake EK, Garcia AM, Loeb S, et al. (2022) Online Medical Misinformation in Cancer: Distinguishing Fact from Fiction. JCO Oncology Practice 18(8): 584-589.

- Baumeister RF, Bratslavsky E, Finkenauer C, Vohs KD (2001) Bad Is Stronger Than Good. Review of General Psychology 5(4): 323-370.

- Ahad AA, Sanchez-Gonzalez M, Junquera P (2023) Understanding and Addressing Mental Health Stigma Across Cultures for Improving Psychiatric Care: A Narrative Review. Cureus 15(5): 1-8.

- Victor M Gardner (2026) The Impact of Stigma on Mental Health: Barriers, Consequences, and Solutions. MI Mind. Henry Ford Health-Detroit, MI. (n.d.). Retrieved December 12, 2025.

- Collaboration is key to countering online misinformation about noncommunicable diseases-new WHO/Europe toolkit shows how. (n.d.). Retrieved December 12, 2025.

- Fake news: a threat to public health. UICC. (n.d.). Retrieved December 12, 2025.

- Infodemics and misinformation negatively affect people’s health behaviors; new WHO review finds. (n.d.). Retrieved December 12, 2025.

- Essack S, Bell J, Burgoyne D, Eljaaly K, Tongrod W, et al. (2023) Addressing Consumer Misconceptions on Antibiotic Use and Resistance in the Context of Sore Throat: Learnings from Social Media Listening. Antibiotics 12(6): 1-16.

- 4 Common Myths, Misconceptions about Antibiotics. Facts & Myths. (n.d.). Retrieved December 12, 2025.

- Jones ASK, Chan AHY, Beyene K, Tuck C, Ashiru-Oredope D, et al. (2024) Beliefs about antibiotics, perceptions of antimicrobial resistance, and antibiotic use: initial findings from a multi-country survey. International Journal of Pharmacy Practice 32: 21-28.

- Public understanding of antibiotics is insufficient, global study finds. CIDRAP. (n.d.). Retrieved December 12, 2025.

- Auta A, Adewuyi EO, Hedima EW, David EA, Balachandran L, et al. (2025) Global and regional knowledge of antibiotic use and resistance among the general public: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Microbiology and Infection Pp: 1-9.

- Song M, Elson J, Haas C, Obasi SN, Sun X, et al. (2025) The Effects of Patients’ Health Information Behaviors on Shared Decision-Making: Evaluating the Role of Patients’ Trust in Physicians. Healthcare 13(11): 1-21.

- Lu Q, Schulz PJ (2024) Physician Perspectives on Internet-Informed Patients: Systematic Review. Journal of Medical Internet Research 26(1): 1-16.

- Shah S (2024) The Influence of Internet-Derived Misinformation on Medical Treatment Decisions: A Social Learning Perspective. Premier Journal of Public Health Pp: 1-11.

- The Effects of Medical Misinformation on the American Public-Ballard Brief. (n.d.). Retrieved December 12, 2025.

- How health misinformation impacts clinical decision-making-Change Makers. (n.d.). Retrieved December 12, 2025.

- Johnson SB, Bylund CL (2023) Identifying Cancer Treatment Misinformation and Strategies to Mitigate Its Effects with Improved Radiation Oncologist-Patient Communication. Practical Radiation Oncology 13(4): 282-285.

- Fridman I, Boyles D, Chheda R, Baldwin-SoRelle C, Smith AB, et al. (2025) Identifying Misinformation About Unproven Cancer Treatments on social media Using User-Friendly Linguistic Characteristics: Content Analysis. JMIR Infodemiology 5(1): 1-18.

- Study finds most cancer patients exposed to misinformation. Researchers pilot “information prescription.” -ecancer. (n.d.). Retrieved December 12, 2025.

- Countering medical misinformation. UICC. (n.d.). Retrieved December 12, 2025.

- Bhattacharya S, Singh A (2025) Unravelling the infodemic: a systematic review of misinformation dynamics during the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Communication 10: 1-12.

- Lazard AJ, Nicolla S, Vereen RN, Pendleton S, Charlot M, et al. (2023) Exposure and Reactions to Cancer Treatment Misinformation and Advice: Survey Study. JMIR Cancer 9: 1-14.

- Cancer Misinformation: Its Impact on Patients and Mitigation Strategies-ILCN.org (ILCN/WCLC). (n.d.). Retrieved December 12, 2025.

- The Challenges of Cancer Misinformation on Social Media-NCI. (n.d.). Retrieved December 12, 2025.

- Treatment refusal by cancer patients: A qualitative study of oncology health professionals’ views and experiences in Australia. (n.d.). Retrieved December 12, 2025.

- Loeb S, Langford AT, Bragg MA, Sherman R, Chan JM (2024) Cancer misinformation on social media. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 74(5): 453-464.

- Statins negative press linked to people stopping treatment-BHF. (n.d.). Retrieved December 12, 2025.

- Nielsen SF, Nordestgaard BG (2016) Negative statin-related news stories decrease statin persistence and increase myocardial infarction and cardiovascular mortality: A nationwide prospective cohort study. European Heart Journal 37(11): 908-916.

- Babak A, Rouzbahani S, Safaeian A, Poonaki F (2025) Diabetes Mellitus Type 2 and Popular Misconceptions: A Cross‐Sectional Study. Health Science Reports 8(10): 1-10.

- The importance of detecting and combating fake news about diabetes. (n.d.). Retrieved December 12, 2025.

- Wang C, Fang B, Regmi A, Yamaguchi Y, Yang L, et al. (2023) Text mining online disinformation about antihypertensive agents ACEI/ARB and COVID-19 on Sina Weibo. Journal of Global Health 13: 1-6.

- Islam MM, De Lacy Vawdon C, Gleeson D (2025) Adverse commercial determinants of health in low- and middle-income countries: a public health challenge. Health Promotion International 40(6): 1-10.

- de Lacy Vawdon C, Vandenberg B, Livingstone C (2023) Power and Other Commercial Determinants of Health: An Empirical Study of the Australian Food, Alcohol, and Gambling Industries. International Journal of Health Policy and Management 12(1): 1-14.

- Maani N, Ci Van Schalkwyk M, Petticrew M (2023) Under the influence: system-level effects of alcohol industry-funded health information organizations. Health Promotion International 38(6): 1-9.

- Lacy Nichols J, Scrinis G, Carey R (2019) The politics of voluntary self-regulation: insights from the development and promotion of the Australian Beverages Council’s Commitment. Public Health Nutrition 23(3): 564-575.

- Savell E, Fooks G, Gilmore AB (2016) How does the alcohol industry attempt to influence marketing regulations? A systematic review. Addiction 111(1): 18-32.

- Smith R, Chen K, Winner D, Friedhoff S, Wardle C (2023) A Systematic Review Of COVID-19 Misinformation Interventions: Lessons Learned. Health Affairs 42(12): 1738-1746.

- Whitehead HS, French CE, Caldwell DM, Letley L, Mounier Jack S (2023) A systematic review of communication interventions for countering vaccine misinformation. Vaccine 41(5): 1018-1034.

- Narang P, Ngo T, Hanfling D, Vasan A, Shah A, et al. (2025) To Mitigate the Health Impacts of Mis- And Disinformation, States Should Mandate Digital Watermarking. Health Affairs Forefront.

- Weiss BD, Mays MZ, Martz W, Castro KM, DeWalt DA, et al. (2005) Quick Assessment of Literacy in Primary Care: The Newest Vital Sign. The Annals of Family Medicine 3(6): 514-522.

- ISPOR Takes Health Research Mainstream with Plain Language Summaries. (n.d.). Retrieved December 17, 2025.

- Infodemic management: protecting people from harmful health information in emergencies. (n.d.). Retrieved December 17, 2025.

- Managing false information in health emergencies: an operational toolkit. (n.d.). Retrieved December 17, 2025.

- Briand S, Hess S, Nguyen T, Purnat TD (2023) Infodemic Management in the Twenty-First Century. Managing Infodemics in the 21st Century: Addressing New Public Health Challenges in the Information Ecosystem Pp: 1-16.

- Combatting misinformation online. (n.d.). Retrieved December 17, 2025.