Background

The relationship between colonial governance and public health has long been recognized as a critical lens through which to understand the enduring effects of political subjugation on population wellbeing. The case of Puerto Rico presents a unique opportunity to examine these dynamics within the context of American territorial expansion and the evolution of federal health policy throughout the twentieth century. As a territory acquired by the United States following the Spanish-American War of 1898, Puerto Rico has occupied an ambiguous political status that has profoundly shaped its health system development and population health trajectories for over a century [1].

The transition from Spanish to American rule marked a fundamental shift in Puerto Rico’s governance structure and public health approach. Unlike other Caribbean territories that eventually achieved political independence, Puerto Rico became embedded within the American federal system while remaining excluded from full political participation. The Foraker Act of 1900 established civilian government without granting citizenship, while the Jones Act of 1917 extended citizenship without voting representation in Congress [2-4]. The establishment of Commonwealth status in 1952 further institutionalized this ambiguous relationship, creating what has been described as a “permanent union” based on common citizenship and currency but with asymmetrical political rights [5-8].

Within this colonial framework, public health became both an instrument of social improvement and a mechanism of political control. The implementation of major federal health legislation in Puerto Rico exemplifies these dynamics. The Hill-Burton Act of 1946, formally known as the Hospital Survey and Construction Act, provided substantial federal funding for hospital construction throughout the United States and its territories [9]. In Puerto Rico, this legislation catalyzed a massive expansion of hospital infrastructure, with federal funds covering two-thirds of construction costs.

Similarly, the introduction of Medicare and Medicaid in 1965 [10] brought new resources while imposing additional constraints. These programs extended health coverage to elderly and indigent populations but required substantial local matching funds set at the maximum rate of 45%, despite the relatively lower per capita income of Puerto Rico’s. This matching requirement consumed an increasing share of the local health budget [11], effectively determining health priorities through federal funding mechanisms rather than local needs assessment.

In this context of the given period, this paper employs a Historical Integrative Policy-Epidemiology Synthesis approach to investigate the evolution of public health policies in Puerto Rico from 1898 to 1969, with particular attention to their relationship to broader political and economic structures under U.S. governance. By examining the intersection of policy implementation, epidemiological outcomes, and political economy, this analysis reveals how colonial health interventions can affect population health and health policy making autonomy. The following sections present the methodology underpinning this integrated analysis, detailed findings across five historical periods, a critical discussion of the implications for understanding colonial health governance, and conclusions regarding the effects of dependent development in health systems.

Methodology

Overview

This study employed a Historical Integrative Policy- Epidemiology Synthesis (HIPES) approach to analyze the relationship between public health policies and population health outcomes in Puerto Rico from 1898 to 1969 as it was implemented in a dissertation published on the same topic in 1994. The dissertation is a comprehensive, chronologically organized integrated analysis of U.S.-Puerto Rico health policy interaction [11].

HIPES combines three interlinked strands of analysis.

• The historical strand reconstructed the chronology of

health policy formulation and implementation using legislative

acts, administrative reports, and program documentation

contained in the source material. These policies are situated

within the broader socio-political and economic context of

U.S. governance, including shifts in political status such as the

Foraker Act (1900)4, Jones Act (1917) [2,3] and Commonwealth

establishment (1952). This chronological reconstruction traces

the evolution from military health interventions to comprehensive

civilian health programs, documenting how each phase reflected

changing priorities and local adaptations.

• The epidemiological strand examined quantitative

indicators including mortality and morbidity rates, life expectancy

disease-specific trends, and maternal and infant health measures

to track changes in population health across key policy periods.

These data were drawn from annual health reports and vital

statistics. The analysis tracks both aggregate improvements and

disparities, examining how different populations experienced

varying health trajectories under successive policy regimes.

• The policy strand evaluates the intent, funding

mechanisms, and administrative structures of major health

programs such as the Hill-Burton Act and Medicare. This analysis

assesses the alignment between program objectives and local

health needs, examining how federal matching requirements,

eligibility criteria, and administrative mandates shaped resource

allocation and service delivery.

Through integrative synthesis, historical narrative, epidemiological trends, and policy analysis are merged. The framework draws on dependency theory and historical institutionalism. The use of dependency theory and historical institutionalism as analytic orientations within HIPES is justified by the colonial context of Puerto Rico’s relationship with the United States. Dependency theory [12-14] provides conceptual tools for understanding how asymmetrical power relationships shape development trajectories, while historical institutionalism explains how initial institutional configurations persist and constrain future options [15-17].

Findings

Historical and Political Context

The transformation of Puerto Rico from Spanish colony to American territory in 1898 established the foundational structures that would shape health policy development between 1898 to 1969. The Spanish-American War’s conclusion brought immediate changes to governance structures yet maintained fundamental colonial relationships that substituted one power for another. Under Spanish rule, Puerto Rico had functioned as an exploited agricultural territory with minimal investment in social infrastructure, including health services. The American occupation initially promised liberation and modernization, with General Nelson Miles declaring the intent to “bring protection” and “bestow upon you the blessings of the liberal institutions of our Government” [18,19].

Bivariate analysis

However, the political arrangements that emerged revealed persistent colonial dynamics wrapped in democratic rhetoric. The Foraker Act of 1900 established civilian government while denying Puerto Ricans American citizenship, creating a status the Supreme Court would later define as an “unincorporated territory” that “belongs to but is not part of the United States” [20]. This ambiguous status had direct implications for health policy, as federal programs could be selectively applied with modifications that typically disadvantaged the Island. The Jones Act of 1917 extended citizenship without voting representation, establishing a pattern of partial inclusion that would characterize all subsequent federal health programs.

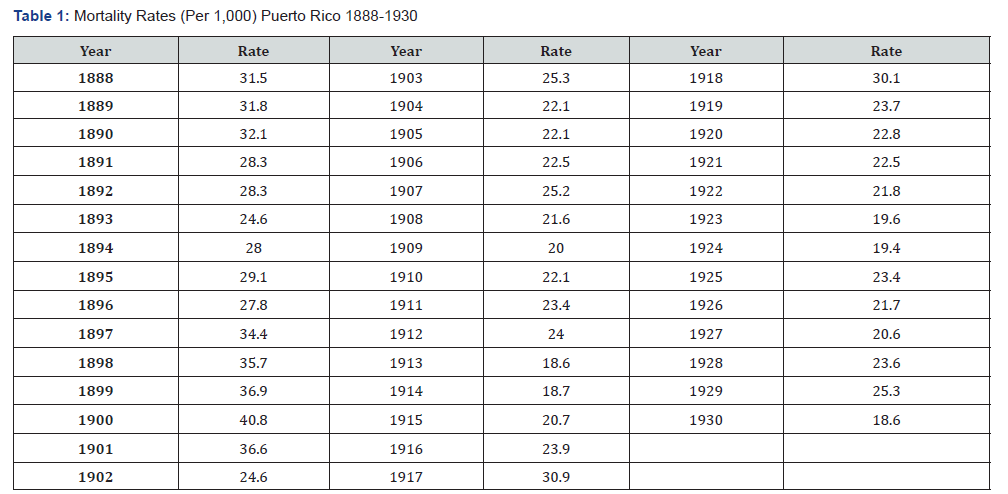

Source: Rivera de Morales, Nydia, “Mortalidad en Puerto Rico: 1888-1967,” Sección de Bioestadística, Escuela de Salud Pública, San Juan, P.R., June 1970 (mimeo).

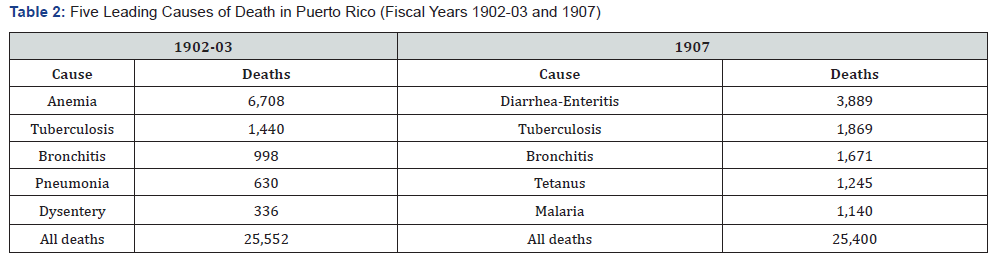

Source: Sanitation Board of Health of Puerto Rico, Reports on Vital Statistics, 1900 to 1908

Source: Rates per 10,000 live births

Source: Puerto Rico’s Annual Budget, 1940 to 1945.

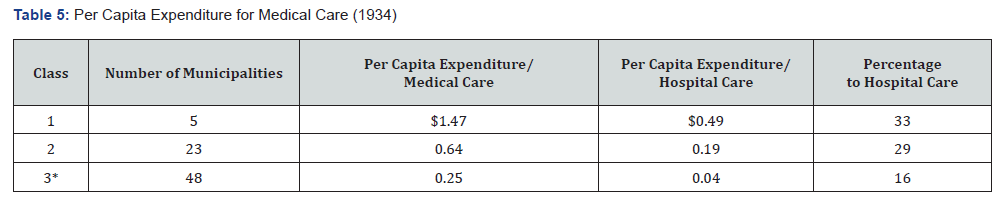

Per capita expenditure for hospital care is a subset within the per capita expenditure for medical care.

*23 of the 48 municipalities had no hospitals.

Source: Illness and Medical Care in Puerto Rico, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1934.

Source: Puerto Rico Department of Health, Annual Health Reports, 1940 to 1964.

Source: Puerto Rico Health Department, Annual Health Reports, 1940 to 1960.

Source: Puerto Rico’s Budget, Years 1967-1983.

Source: Information Please Almanac-Atlas and Yearbook 1990; 43rd edition, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1990.

The shift from diversified agriculture to sugar monoculture altered disease patterns and concentrated populations in ways that facilitated disease transmission [21]. By 1930, sugar production dominated the economy, with American corporations controlling vast estates while the majority of Puerto Ricans lived in poverty. Studies from 1934 revealed that 90% of families earned less than $500 annually, with only 4% earning $1,000 or more [22] This economic structure created massive health disparities and limited local capacity to fund health services independently.

The establishment of Commonwealth status in 1952 institutionalized these dependent relationships while suggesting self-governance [8,23]. The new constitution guaranteed various social rights, including healthcare, but federal relations remained largely unchanged. Most significantly, Puerto Rico retained no influence over federal policies affecting the Island, including health legislation. This political framework meant that health planning occurred within externally imposed constraints, with local authorities implementing programs designed for mainland contexts without adaptation possibilities.

Early Health Interventions under Military and Civilian Rule

The initial American health interventions from 1898- 1930 established patterns of external control and selective modernization that would persist throughout the century. Military Order 91 in 1899 created the Superior Sanitation Board, replacing the ineffective Spanish system with a structure dominated by American military physicians [24]. Early interventions focused primarily on diseases threatening American troops, including yellow fever, smallpox, and venereal diseases, while endemic conditions affecting Puerto Ricans received less attention [25,26].

Mortality data from this period reveals both the severity of health challenges and the limited impact of early interventions. Death rates fluctuated dramatically, from 24.6 per 1,000 population in 1893 to 40.8 in 1900, before gradually declining to 18.6 by 1930 (Table 1). The leading causes of death in 1902- 03 were anemia (6,708 deaths), tuberculosis (1,440), bronchitis (998), pneumonia (630), and dysentery (336), reflecting the predominance of poverty-related conditions (Table 2). By 1907, diarrhea-enteritis had become the leading cause with 3,889 deaths, followed by tuberculosis (1,869), bronchitis (1,671), tetanus (1,245), and malaria (1,140).

The discovery that anemia resulted from hookworm infection rather than dietary deficiency illustrated both American medical capabilities and cultural misunderstandings. Lieutenant Bailey Ashford’s identification of hookworm as the cause led to successful treatment campaigns, with 33 anemia control centers established by 1907 [27]. However, American officials’ initial insistence that Puerto Ricans change their diet to include more meat reflected profound misunderstanding of local economic realities and cultural practices. Similarly, efforts to reduce infant mortality by promoting hospital births failed because they ignored cultural preferences for home delivery and the practical impossibility of reaching distant hospitals [26].

Sanitation campaigns epitomized the authoritarian nature of American health governance. Sanitary inspectors were granted “full access, ingress, and egress to and from all places of business, factories, farms, buildings” with power to enforce compliance [28]. While these measures improved environmental conditions in some areas, they were implemented without community consultation or adaptation to local contexts.

Institutionalization and Expansion of Health Services

The period from 1930-1945 witnessed dramatic expansion of health infrastructure catalyzed by Depression-era federal programs and wartime investments. Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA) funds enabled construction of 19 public health units between 1933-34, while Civil Works Administration resources supported five district hospitals with 1,200 total beds [29]. These investments transformed Puerto Rico’s health landscape, yet embedded dependencies on external funding.

The epidemiological profile during this period showed both progress and persistent challenges. Tuberculosis mortality peaked at 337 per 100,000 population in 1933 before declining through expanded treatment programs. Diarrhea-enteritis overtook tuberculosis as the leading cause of death by 1936-37, responsible for 16.1% of all deaths. Malaria affected 300,000 people, one-fifth of the population, concentrated in coastal sugar-growing areas where standing water provided mosquito breeding grounds [30]. The disease’s association with sugar production illustrated how economic structures shaped disease patterns.

Maternal and infant mortality improvements demonstrated both achievements and limitations of expanded services (Table 3). Maternal mortality declined from 64.6 per 10,000 live births in 1930 to 31.9 by 1945, while infant mortality decreased from 158 to 93.4 per 1,000 live births [31]. These improvements resulted from midwife training programs, milk distribution stations, and prenatal clinics, yet rates remained far higher than mainland levels. The establishment of 160 milk stations exceeded the number of municipalities, funded through horse racing revenues after federal funds ended, illustrating creative local responses to federal funding limitations.

Healthcare financing revealed growing disparities and municipal fiscal crisis (Table 4). The global government budget increased from $16.5 million in 1940 to $149.3 million by 1945, yet health’s share declined from 13.9% to 8.1%. Municipal spending varied dramatically, with per capita health expenditures ranging from $1.47 in five wealthy municipalities to $0.25 in 48 poor ones (Table 5) [22] This disparity led to the recognition that municipalities could not fulfill health responsibilities, necessitating increased “state” assumption of these functions, though this merely shifted dependency from local to insular government still constrained by federal requirements.

The Hill-Burton Act and Health Infrastructure Development

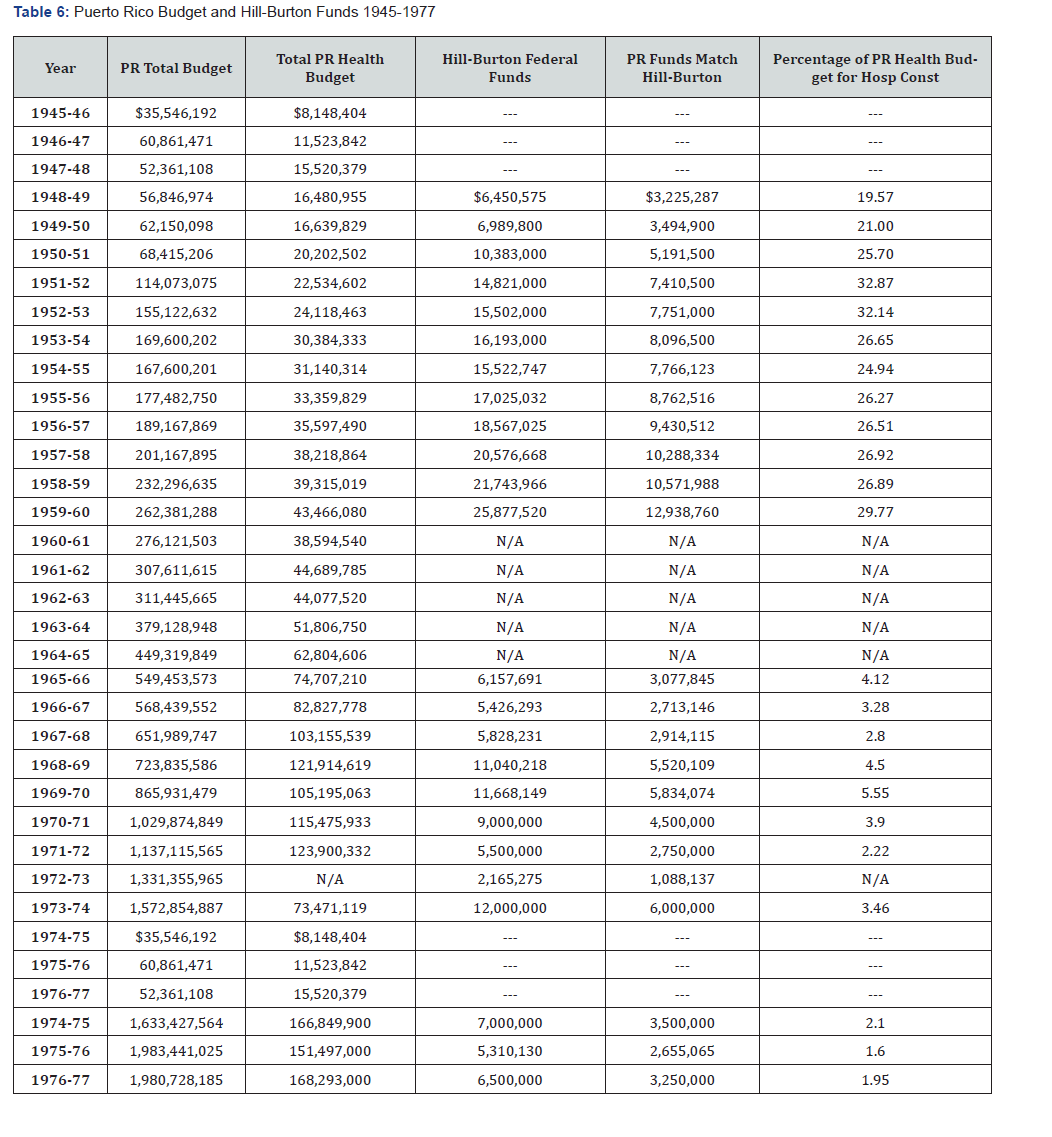

The Hill-Burton Act’s implementation from 1946-1960 fundamentally restructured Puerto Rico’s health system toward hospital-based care, creating infrastructure that would shape service delivery patterns [9,32]. Federal funds totaling $112.6 million supported 103 projects, matched by $115.3 million in local funds despite Puerto Rico’s eligibility for more favorable matching ratios based on per capita income (Table 6). This massive investment produced significant infrastructure expansion yet diverted resources from preventive services as hospitals consumed increasing operational budgets.

The 1947 survey establishing Hill-Burton priorities revealed severe infrastructure deficits and distribution inequities. Existing facilities met only 63.7% of general hospital bed needs, 16% for tuberculosis, 12.9% for mental illness, and 1.5% for chronic disease. Moreover, 50.2% of beds were in government facilities serving the indigent, compared to 26.1% nationally, while proprietary hospitals controlled 33.6% versus 8.3% nationally. This distribution reflected Puerto Rico’s poverty, with 80% of the population unable to afford private care, creating demand for public services that far exceeded capacity [33,34].

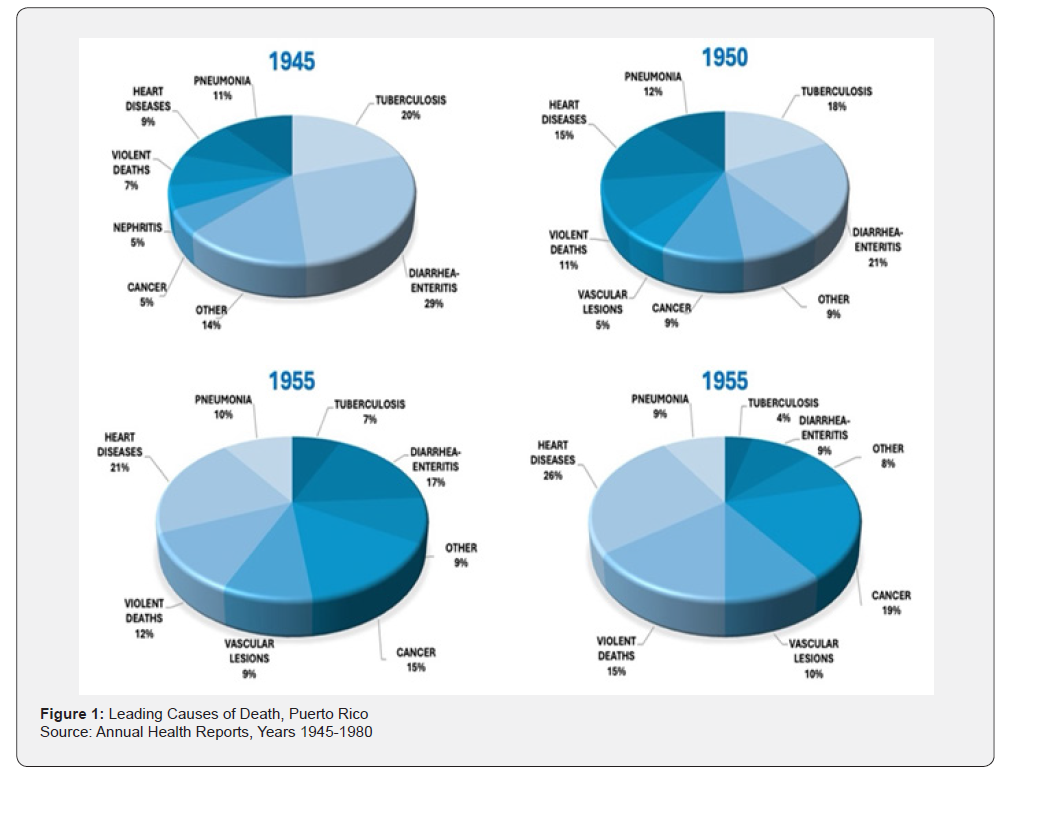

The epidemiological transition during this period justified infrastructure investment while revealing emerging challenges (Figure 1). Heart disease became the leading cause of death by 1960, followed by cancer and cerebrovascular disease, while infectious diseases declined dramatically. Malaria was eradicated through combined environmental and treatment interventions, making Puerto Rico the first territory to achieve this through organized public health efforts. Infant mortality plummeted from 105.3 per 1,000 live births in 1944 to 44.7 by 1960 (Table 7), while life expectancy increased from 46 years in 1940 to 69.4 by 1960 (Table 8).

The regionalization model introduced in 1956 attempted to integrate preventive and curative services through five regions, each anchored by a district hospital supporting municipal health centers. This structure, promoted by a Rockefeller Foundation consultant, promised service coordination and efficiency. One of the pioneers of this model was Dr Guillermo Arbona, a Puerto Rican physician, and later this model was adopted by several countries to improve the quality of care and to properly utilize available resources [35-37]. However, implementation revealed fundamental tensions between the hospital-centric Hill-Burton model and primary care needs. Hospitals claimed increasing budget shares for operations, limiting resources for health centers that could address emerging chronic diseases through prevention and early intervention. By 1960, Puerto Rico had built an American-style hospital system unsuited to its epidemiological needs and fiscal capacity.

The Arrival of Medicare and Medicaid and New Health Policies

The implementation of Medicare and Medicaid from 1965- 1969 brought substantial new resources while fundamentally altering Puerto Rico’s health financing and priorities [10]. Federal health funding increased from 20% of the health budget in 1963- 64 to 54% by 1968-69, with Medicare/Medicaid consuming everlarger shares [11,38]. However, matching requirements set at the maximum 45% rate, despite Puerto Rico’s per capita income warranting an 83% federal share under standard formulas, created severe fiscal strain that led to the distortion of local priorities.

The demographic and epidemiological context where chronic and degenerative diseases were rising, revealed both the programs’ relevance and limitations [38]. By 1965-1969, chronic and degenerative diseases accounted for 52.7% of deaths, up from 38.6% in 1960-1964, while infectious diseases declined to 12.8% from 24.2%. The elderly population requiring Medicare services comprised only 6% of the population yet consumed disproportionate resources through matching requirements [39,40]. This allocation pattern neglected the 37.5% of the population under 15 years and working-age adults facing rising chronic disease burdens.

Program participation expanded rapidly but unevenly, reflecting both demand and structural barriers. Medicare Part A covered 155,000 of 160,369 eligible elderly automatically, while Part B’s voluntary enrollment reached only 91,000 due to premium requirements [38]. Private hospitals certified for Medicare increased from 32 in 1966 to 126 by 1968, as physicians recognized revenue opportunities. These small, physician-owned facilities proliferated without coordination, fragmenting care and increasing costs. Medicaid’s $20 million federal cap, regardless of need or population, further constrained coverage expansion for the indigent majority.

The fiscal impact proved transformative and distortionary. Medicare matching consumed 4.7% of Puerto Rico’s health budget in 1967, rising to 15.6% by 1970 and projected to reach 30.6% by 1980 [11]. (Table 9) Since, a large part of the health budget became committed to federal matching, Puerto Rico lost capacity to address priorities not aligned with federal programs. Furthermore, categorical programs for mental health, maternal and child health, and family planning [41] created vertical silos reporting to federal agencies rather than regional health directors, fragmenting the recently established regionalization model and increasing administrative costs [37].

The creation of planning infrastructure represented both achievement and constraint. Federal requirements necessitated establishment of comprehensive health planning boards and sophisticated accounting systems for federal funds. While these structures improved administrative capacity, they oriented planning toward securing federal funds rather than addressing local needs. The Consulting Board for Global Planning identified fundamental problems: inability to meet service demands, continuous cost increases, inadequate financing, and insufficient specialized personnel [38]. Yet solutions remained constrained by federal program parameters designed for mainland contexts.

Synthesis

The trajectory of Puerto Rico’s health system from 1898 to 1969 reveals how successive federal interventions produced significant health improvements while embedding structural dependencies that constrained autonomous development. Each major policy initiative addressed health needs yet created institutional patterns that limited future flexibility. The Hill- Burton Act built essential infrastructure but oriented the system toward expensive hospital care unsuited to emerging chronic disease patterns. Medicare and Medicaid expanded coverage but consumed local resources through matching requirements that ignored Puerto Rico’s economic reality. The cumulative effect was a health system that achieved remarkable mortality reductions and service expansion but remained fundamentally dependent on external resources and priorities, unable to adapt programs to local contexts or shift resources as epidemiological needs evolved. This paradox of simultaneous achievement and constraint illustrates how colonial health interventions can improve population health while reinforcing political subordination, creating systems that deliver benefits but limit self-determination.

Discussion

The transformation of Puerto Rico’s health system between 1898 and 1969 exemplifies the fundamental contradictions inherent in colonial modernization projects. The quantitative achievements are undeniable: infant mortality declined by 92%, life expectancy more than doubled, and infectious diseases that had plagued the population for centuries were largely controlled. Yet these improvements occurred within and reinforced structures of dependency that constrained Puerto Rico’s ability to develop health policies aligned with local needs and priorities. This paradox challenges simplistic narratives about colonial intervention, revealing how health improvements can serve as mechanisms of political control even while delivering tangible benefits.

The implementation of federal health programs consistently reflected metropolitan priorities rather than local epidemiological needs. The Hill-Burton Act’s emphasis on hospital construction, as evidenced in the creation of facilities that met only 63.7% of general bed needs while achieving just 1.5% of chronic disease bed requirements, illustrates this misalignment. The program responded to mainland America’s post-war hospital shortage but ignored Puerto Rico’s greater needs for primary care and preventive services. Similarly, Medicare’s focus on the elderly, who comprised only 6% of Puerto Rico’s population in 1969, diverted resources from the 37.5% under age 15 who faced preventable infectious diseases and the working-age population confronting rising chronic disease burdens without adequate primary care access.

The matching fund requirements embedded in federal programs created particularly pernicious forms of dependency. Despite Puerto Rico’s per capita income being less than half of Mississippi’s, the poorest state, matching rates were set at maximum levels, consuming ever-increasing shares of local health budgets. Medicare matching alone grew from 4.7% of the health budget in 1967 to a projected 30.6% by 1980 (Table 9), effectively determining health priorities through federal funding availability rather than epidemiological assessment. This fiscal architecture meant that Puerto Rico had to orient its health system toward securing federal funds, regardless of whether federal programs addressed local priorities.

The epidemiological transition documented across the study period further complicated these structural constraints. As infectious diseases declined and chronic conditions emerged as leading causes of death, the hospital-centric system built through Hill-Burton became increasingly misaligned with population needs. The shift from infectious diseases causing 24.2% of deaths in 1960-1964 to chronic diseases accounting for 52.7% by 1965-1969 demanded preventive services and primary care that the hospital-based system could not efficiently provide. Yet path dependencies created by massive hospital investments and ongoing operational costs prevented system reorientation toward prevention and health promotion.

Dependency theory illuminates how this health interventions reinforced Puerto Rico’s peripheral status within the American imperial system [21,42]. Health programs functioned as mechanisms for extending metropolitan control while creating sufficient benefits to maintain legitimacy. The requirement that Puerto Rico match federal funds at the highest rates, despite its lower income, extracted local resources for federally determined priorities, preventing autonomous development of health strategies suited to local conditions. The proliferation of categorical programs, each with separate reporting requirements and vertical management structures, fragmented the regionalization model that represented Puerto Rico’s own attempt at system integration, subordinating local planning to federal program logic [37].

The colonial nature of these arrangements becomes particularly evident when examining decision-making processes. Puerto Rico had no voting representation in Congress when health legislation was crafted, no ability to modify matching requirements, and limited flexibility in program implementation [8,43]. Health planning occurred within parameters established in Washington for mainland contexts, with local authorities restricted to implementation roles. This exclusion from policy formulation while bearing implementation costs represents a classic colonial relationship, where the periphery must accept metropolitan decisions regardless of local preferences or needs.

The creation of administrative infrastructure for federal programs illustrates another dimension of dependent development. Sophisticated planning boards, accounting systems, and reporting mechanisms developed to meet federal requirements, as seen in the establishment of the Planning, Investigation, and Evaluation Unit in 1967 [38]. While these structures improved administrative capacity, they oriented bureaucratic effort toward federal compliance rather than local innovation. Professional expertise developed in navigating federal programs rather than designing locally appropriate interventions, creating human capital dependencies that paralleled fiscal ones.

Cultural dimensions of health interventions revealed persistent colonial attitudes despite technical modernization. Early American efforts to promote hospital births ignored cultural preferences and practical barriers, attributing resistance to “lack of intelligence” rather than recognizing legitimate concerns [26,27]. The assumption that Puerto Ricans should adopt American dietary habits to address anemia, despite economic inability to afford meat, exemplified metropolitan inability to understand local contexts. Even successful interventions like hookworm treatment succeeded only when they acknowledged local realities, yet such recognition remained exceptional rather than systematic.

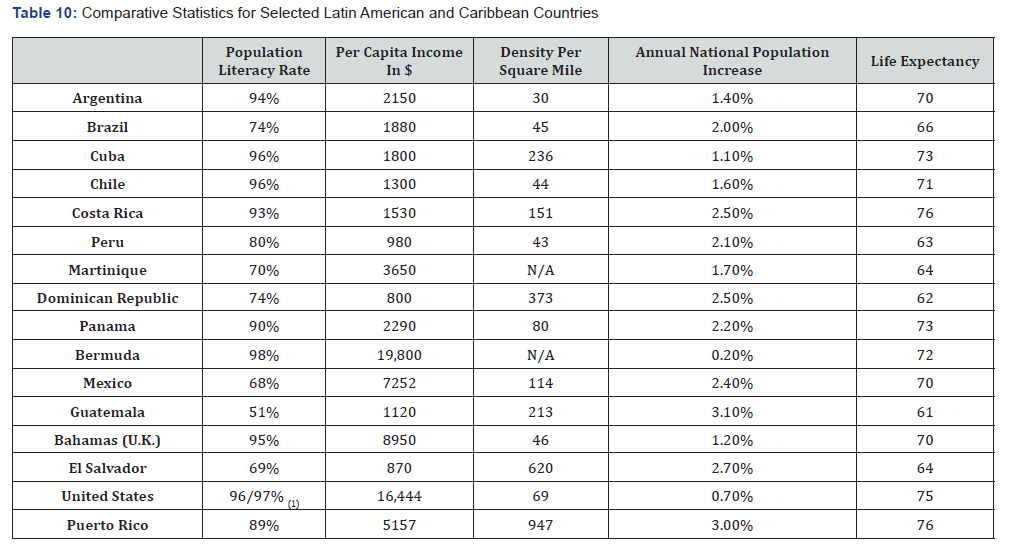

The comparison with Latin American and Caribbean neighbors provides crucial context for evaluating these colonial health interventions. Puerto Rico achieved substantial reductions in infant mortality from 244 per 1,000 live births in 1898 to 19 per 1,000 by 1980 (14.2 per 1,000 in 1987) than any other regional country, higher per capita income ($5,157 in 1988), and better infrastructure development [40]. (Table 10) These superior outcomes might suggest that colonial dependency brought net benefits. However, this comparison obscures how dependency constrained Puerto Rico’s potential for autonomous development and potentially better outcomes. The relevant counterfactual is not how Puerto Rico fared relative to other exploited territories, but what might have been achieved with the same resources under local control aligned with local priorities [42].

The transformation from Spanish to American colonialism represented a modernization of imperial control rather than liberation [6,7]. Where Spain extracted resources through direct appropriation, American colonialism operated through structural adjustment that appeared beneficial while maintaining dependencies. Health programs exemplified this sophisticated control, providing sufficient benefits to ensure acceptance while structuring relationships to preclude independence. The result was a health system that achieved remarkable improvements in aggregate indicators while remaining fundamentally unable to adapt to changing needs or develop autonomous capacity for innovation.

Conclusion

This analysis of Puerto Rico’s health system evolution from 1898 to 1969 demonstrates how colonial interventions in public health can simultaneously produce measurable improvements in population health while embedding structural dependencies that constrain policy autonomy and self-determination. The dramatic reductions in mortality, doubling of life expectancy, and control of infectious diseases represent genuine achievements that improved millions of lives. Yet these gains occurred through mechanisms that reinforced Puerto Rico’s political subordination and prevented development of health policies aligned with local epidemiological needs and cultural contexts.

The Historical Integrative Policy-Epidemiology Synthesis (HIPES) methodology employed in this study proves particularly valuable for analyzing such complex colonial interventions. By integrating historical policy analysis, epidemiological trend analysis, and political economy perspectives, HIPES reveals patterns that may get overlooked in conventional approaches that examine health outcomes in isolation from political structures and other historical contexts. This methodology illuminates how health policies function simultaneously as instruments of social welfare and mechanisms of political control, delivering benefits while denying autonomy. The approach developed here offers a framework applicable to contemporary analyses of development assistance, where similar dynamics of improvement alongside dependency continue to characterize relationships between donor and recipient states.

The Puerto Rican experience from 1898 to 1969 reveals consistent patterns across successive federal interventions. The Hill-Burton Act created essential hospital infrastructure but locked Puerto Rico into an expensive, curative-oriented system unsuited to its epidemiological transition toward chronic diseases. Medicare and Medicaid expanded coverage for vulnerable populations but did so through matching requirements that consumed local resources and determined health priorities through federal funding targets rather than local needs assessment.

The colonial relationship fundamentally shaped these outcomes through multiple mechanisms. Exclusion from federal policy formulation meant Puerto Rico had to implement programs designed for mainland contexts without meaningful modification possibilities. Matching fund requirements set at maximum levels despite lower per capita income extracted local resources for federally-determined priorities. Categorical program structures fragmented local planning efforts and created vertical reporting relationships that bypassed territorial health authorities. The cumulative effect was a health system that achieved remarkable aggregate improvements while remaining structurally dependent on external resources and priorities.

Yet recognizing benefits should not obscure fundamental costs in autonomy and self-determination. The inability to design health policies responsive to local epidemiological patterns, cultural preferences, and fiscal capacities represents a profound constraint on development potential. Resources equivalent to those provided through federal programs, if controlled locally, might have produced different but potentially more sustainable and appropriate health systems. The hypothetical possibility of autonomous development with similar resources highlights how dependency constrains not just present choices but future possibilities.

The implications extend beyond Puerto Rico to illuminate dynamics characterizing contemporary development assistance globally. Many countries receiving health aid experience similar patterns of improvement alongside dependency, where donor priorities shape health systems which are not always aligned with local needs. The distortionary effects of disease-specific funding, vertical program structures, and conditional aid mirror patterns evident in Puerto Rico’s federal health programs. Understanding these historical precedents provides crucial context for reforming global health governance toward more equitable partnerships that deliver benefits without perpetuating subordination. The task for contemporary global health must not merely be to deliver health improvements but to do so through mechanisms that enhance rather than diminish the capacity for self-determination among recipient populations.

References

- Jones Act (1917) World of 1898: International Perspectives on the Spanish American War- Research Guides at Library of Congress.

- Jones Shafroth Act (1917) A Latinx Resource Guide: Civil Rights Cases and Events in the United States-Research Guides at Library of Congress.

- Foraker Act (Organic Act of 1900) World of 1898: International Perspectives on the Spanish American War-Research Guides at Library of Congress.

- Public Law 447: JOINT RESOLUTION (1952) Approving the constitution of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico which was adopted by the people of Puerto Rico Pp: 327-328.

- Silvestrini BG, L de S (1987) History of Puerto Rico: trajectory of a people. Puerto Rico: Cultural Puertorriqueñ

- Morales Carrión A, Caro Costas AR (1983) Puerto Rico, a political and cultural history. Morales Carrión Arturo, Caro Costas AR, American Association for State and Local History, editors. New York: W.W. Norton Pp: 1-384.

- (1966) Status of Puerto Rico: Selected background studies prep. for the United States-Puerto Rico Commission on the Status of Puerto Rico. Washington US Gov Print Office.

- Hoge VM (1946) The Hospital Survey and Construction Act Bulletin Pp: 15-17.

- Medicare and Medicaid Act (1965) National Archives.

- Puerto Rico Budget. Years 1940-1980. Treasury Department, San Juan, Puerto Rico.

- Gonzalez A R (1994) Health and development: The United States/Puerto Rican case [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Johns Hopkins University.

- Oliveira FA de (2024) Dependency Theory after Fifty Years: The Continuing Relevance of Latin American Critical Thought. J Lat Am Stud 56(2): 355-357.

- Sanchez O (2003) The Rise and Fall of the Dependency Movement: Does It Inform Underdevelopment Today? EIAL - Estudios Interdisciplinarios de América Latina y el Caribe 14(2).

- Cardoso FH, Faletto E (1979) Dependency and development in Latin America Pp: 1-227.

- Steinmo S (2012) Historical institutionalism. Approaches and Methodologies in the Social Sciences: A Pluralist Perspective Pp: 118-38.

- Pan W, Hosli MO, Lantmeeters M (2023) Historical institutionalism and policy coordination: origins of the European semester. Evolutionary and Institutional Economics Review Aug 20(1): 141-167.

- Fioretos O, Falleti TG, Sheingate A (2016) The Oxford Handbook of Historical Institutionalism. Oxford University Press.

- Open letter to Puerto Ricans from General Nelson A. Miles; July 28, 1898, File 655-3, Records of the Bureau of Insular Affairs, Record Group 350, National Archives, Washington DC.

- United States. Porto Rico Special Commissioner (1990) Report on the island of Porto Rico; its population, civil government, commerce, industries, productions, roads, tariff, and currency, with recommendations. Library of Congress Washington DC USA.

- Downes V Bidwell 182 U.S. 244 (1901) Justia US Supreme Court Center.

- Imperialist Initiatives and the Puerto Rican Worker: From Foraker to Reagan on JSTOR.

- Mountin, Joseph W Walter (1891-1952) Illness and medical care in Puerto Rico / by Joseph W. Mountin, Elliott H. Pennel, Evelyn Flook; prepared by direction of the surgeon general. Washington GPO.

- (1990) Puerto Rico: Information for Status Deliberations: Briefing Report to the Chairman, Subcommittee on Insular and International Affairs, Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs, House of Representatives. US General Accounting Office Pp: 1-71.

- Military Government of Porto Rico, from October 18, 1898, to April 30, 1900: Appendices to the Report of the Military Governor-Puerto Rico. Military Governor (1899-1900: Davis) Pp: 1-359.

- Puerto Rico Department of Health. Annual Health Report (1900-1901). San Juan PR: Department of Health.

- Costa Mandry O Oscar (1971) Apuntes para la historia de la medicina en Puerto Rico: breve reseña histórica de las ciencias de la salud-National Library of Medicine Institution. San Juan, P.R.: Departmento de Salud, Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico.

- Ashford BK (1998) A soldier in science: the autobiography of Bailey K Ashford, Colonel MC, USA Pp: 1-425.

- Puerto Rico. Superior Board of Health (1904) Report and vital statistics of the Superior Board of Health of Porto Rico: San Juan, PR, May 1st, 1900 to June 30, 1903. National Library of Medicine Institution Pp: 1-233.

- Puerto Rico Department of Health. Annual Health Reports 1930-1945. San Juan, PR: Department of Health.

- Mintz, Sidney Wilfred (1960) Worker in the cane; a Puerto Rican life history Pp:1-325.

- Puerto Rico Department of Health, Annual Health Report years 1930, 1935, 1940 and 1945.

- Puerto Rico Legislature (147) P.L. 50, Enabling Act to Hospital Survey and Construction Act Pp: 126-145.

- Commission on Hospital Care, Hospital Care in the United States (1948) The Commonwealth Fund.

- Consejo de Hospitales de Puerto Rico. Servicios Hospitalarios en Puerto Rico, 1945.

- Ramos MC, Barreto JOM, Shimizu HE, de Moraes APG, da Silva EN (2020) Regionalization for health improvement: A systematic review. PLoS One 15(12): 1-20.

- Santos Lozada AR (2010) Transformations of public healthcare services in Puerto Rico from 1993 until 2010 Pp: 1-12.

- Arbona G, Ramírez de Arellano, Annette B (1978) Regionalization of health services: the Puerto Rican experience. Oxford: International Epidemiological Association.

- Puerto Rico (1968) Annual Report-Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, Department of Health. The Department.

- José L Vázquez Calzada (1988) La Población de Puerto Rico y su Trayectoria Histó San Juan Pp: 1-387.

- Cooperative Health Statistics System (1980) San Juan Puerto Rico: Department of Health.

- Public Law 91-572: Family Planning Services and Population research Act of 1970 Pp: 1504-1508.

- V Navarro (1974) The Underdevelopment of Health or the Health of Underdevelopment: An Analysis of the Distribution of Human Health Resources in Latin America. Jstor 4(1): 5-27.

- PUERTO RICO (1990) Information for Status and Deliberations by La Colección Puertorriqueña-Issuu.