Introduction

The disjunction between donor priorities and national health needs has long shaped the discourse around Development Assistance for Health (DAH). While DAH has contributed to substantial gains in targeted health outcomes at the country level [1], particularly infectious diseases, the architecture of aid often reconfigures national health priority setting in ways that diverge from local epidemiological profiles and health system-strengthening (HSS) plans [2-6]. Despite global commitments to ownership and alignment with national needs, analyses reveal that donor funding is often only weakly correlated with country-level disease burden. Studies examining resource allocation patterns reveal substantial discrepancies between DAH distribution and national burdens of disease, including large differentials in funding for HIV, malaria, and immunization relative to non-communicable diseases (NCDs) and mental health [7,8].

Vertical, disease-specific programs, while highly effective in improving measurable outcomes for a small set of diseases, have been shown to redirect attention, human resources, and governance capacity away from primary health care functions and longterm HSS [4,9-11]. These dynamics have been documented across diverse contexts, where parallel supply chains, data systems, and supervisory structures created by aid initiatives can place additional demands on already constrained national systems [4,5,12]. It skews national policies towards some disease areas and less towards others. This phenomenon is described as agenda distortion- when donor funding priorities reorient national health policy focus away from local burden of disease or system needs towards donor-preferred programs [13,14]. This happens at both the global [15] and national level. This study focuses on the national level health agenda distortion since it is the locus of context-based sustainable policy action, which is especially pertinent given the current trend of declining aid and a trend towards national health sovereignty [16,17].

The friction between donor interest and recipient need constitutes one of the central tensions in global health aid governance [18] and continues to influence how recipient countries allocate resources, design programs, and conceptualize long-term health system planning [19]. Agenda distortion can occur through overt mechanisms, such as earmarked funding and performance measurement frameworks, or more subtly through the exercise of various forms of power by shaping norms and expectations about what constitutes an adequate health response.

DAH fungibility and substitution reinforce this concern; evidence from multi-country analyses indicates that DAH inflows reduce domestic public spending on health by substituting for national allocations rather than supplementing them, thereby weakening local accountability and long-term commitments to system financing [20-23]. Related studies demonstrate that fragmented and earmarked aid with short-term commitments aggravate the problem by generating volatility [24] and administrative burdens that divert limited governmental capacity toward donor-specific processes, reinforcing externally driven decision-making at the expense of unified sector strategies [25-28].

The global policy response to these challenges emerged through the aid-effectiveness agenda set out in the Paris Declaration (2005) [29], Accra Agenda for Action (2008) [30], and Busan Partnership (2011) [31] which articulated principles of ownership, alignment, harmonization, results, and accountability. Health-sector adaptations, such as the International Health Partnership (IHP) and later UHC2030, encouraged partners to align their support with a single national strategy and to use common assessment and review mechanisms [32,33]. Despite these efforts, evaluations show that fragmentation, misalignment, and agenda distortion persist, driven by institutional mandates, accountability requirements, power differentials, and divergent donor priorities [25].

These tensions have become more salient in the current era of declining DAH. Pressures to transition from donor financing to domestic self-sufficiency have intensified, with low- and middle- income countries encouraged to assume greater responsibility for sustaining the financing and planning of programs historically funded by external actors. Transition readiness assessments conducted across diverse contexts, including Cambodia, Sri Lanka, and Botswana, demonstrate that while countries may experience epidemiological improvements because of aid, external dependencies often remain embedded through governance arrangements and financing structures [34-39]. A historical analysis of more than six decades of data in Puerto Rico in a post-colonial environment concluded with similar findings [37,40,41]. The paradox is that health systems supported by donor investments may simultaneously be constrained by them, particularly where political, fiscal, or institutional capacity to absorb and sustain programs remains limited.

Against this backdrop, this study examines the gaps within global policy frameworks that aim to support national leadership and sustainability of health financing and planning but often fall short in addressing them. By synthesizing evidence on agenda distortion, power dynamics in donor-recipient relationships, and the limitations of existing aid effectiveness instruments, the study aims to illuminate the structural and procedural shortcomings of policies that fail to prevent misalignment and dependency. The study proposes policy recommendations to minimize agenda distortion while strengthening aid effectiveness, self-sufficiency, and sustainability.

Methods

Study design and analytic orientation

This study employed a hybrid methodological design integrating the Historical Integrative Policy-Epidemiology Synthesis (HIPES) [37] approach with Critical Interpretive Synthesis (CIS) [42]. The combination of these two methodological lenses enabled both a historically grounded assessment of how aid-related policies have evolved, their unintended effects, and an interpretive analysis of aid effectiveness frameworks.

HIPES analytic strand

HIPES provided the overarching structure for situating donor-

recipient interactions within broader historical and political-

economic trajectories, which shaped the aid effectiveness

frameworks [37]. HIPES integrates three strands of inquiry:

1. Historical policy evolution: tracing shifts in health aid

amounts, focus areas, channels, and global development

frameworks from the early 2000s to the current era. This included

analysis of major donor policy documents, aid-effectiveness

frameworks, and transition readiness assessments.

2. Epidemiological alignment and health needs: examining

whether donor-supported priorities reflect domestic disease

burdens and system requirements, using a narrative literature

review drawing on evidence from comparative studies

on DAH allocation.

3. Political economy of aid and aid-effectiveness policy frameworks:

interrogating how institutional incentives, governance

arrangements, and asymmetrical power relations

shape priority setting, program design, and implementation.

Critical Interpretive Synthesis

Critical interpretive synthesis guided the analysis by helping bring together findings from different types of literature and policy documents. Instead of only summarizing what each source says, this approach looked for patterns, assumptions, and gaps that shape how problems are understood. It allowed the study to compare different viewpoints, incorporate implicit researcher reflexivity, and identify where policy narratives may lead to distortions.

Data sources

• Peer-reviewed empirical studies on DAH flows, misalignment,

fungibility, substitution, system effects, and power dynamics;

theories of power in global governance [39,43].

• Donor policy instruments such as the Paris, Accra, and

Busan agreements [29-31].

• Global health financing frameworks such as the Global

Fund Sustainability, Transition and Co-financing policy (STC)

[44], Gavi transition policies [45], PEPFAR Sustainability Index

and Dashboard (SID) [46], and the Global Financing Facility (GFF)

Strategy 2021-2025 [47].

• Policy and technical documents were reviewed, including

the UHC2030 frameworks [32,33] and the Joint Assessment of

National Health Strategies (JANS) [48].

• Other relevant documents, such as the WHA resolutions

on sustainable financing [46,49].

Donor Funding Attributes, Role of Power, and Aid Effectiveness Frameworks

The evolution of DAH reflects a complex interplay of normative aspirations for national ownership and the reality of donor- driven influence [4]. Early commitments to aid effectiveness were grounded in the principles of alignment, harmonization, and mutual accountability, codified through the Paris Declaration (2005) [29], Accra Agenda for Action (2008) [30], and Busan Partnership for Effective Development Co-operation (2011) [31]. These agreements aimed to shift control over health policy and financing from donors to governments by promoting the use of national systems, national plans, and unified sector review mechanisms with the expectation of accountability, ownership, and fair use of resources [50-52]. Yet, while these frameworks established the vocabulary of autonomy, evidence suggests that their implementation has been limited, uneven, and undermined by broader political economy dynamics and power differentials [53-55]. The distribution, design, and conditionalities of aid reflect complex negotiations between donor agencies, global initiatives, and recipient governments. These negotiations are embedded in power relations that influence not only the allocation of resources but also the definition of priorities and acceptable interventions [56].

Evolution of DAH and its structural effects

The expansion of DAH from the early 2000s was characterized by rapid growth in vertical initiatives and global health partnerships [57]. A study on DAH trends noted that during roughly 2000-2010, health aid grew at about 11% per year on average, with much of this increase going to HIV/AIDS, TB, malaria, and vaccines, and being channeled through global health partnerships like the Global Fund and Gavi rather than traditional bilateral donors [58,59]. Global health partnerships and donor institutions such as PEPFAR introduced program architectures that relied heavily on earmarked funding, short-term performance metrics, and parallel implementation systems. Although these generated substantial gains in disease control and treatment coverage, they also created systemic dependencies [4,5,57,60-63]. For example, a study noted that Global Fund support improved Zimbabwe’s procurement and supply chain efficiency through new infrastructure, data systems, warehouse optimization, and trained personnel. However, it also created a system where different donor-funded commodities followed separate protocols, leading to inefficiencies and dependence [64].

Another study analyzing DAH from 2005 to 2017 found that DAH was positively associated with the burden of HIV, TB, and malaria, and this alignment improved over time for these specific diseases. However, this focus excluded NCDs and other major burdens, which remain significantly underfunded by DAH relative to their disease burden [65]. For example, despite NCDs accounting for nearly 50% of global disease burden in 2015 and rising, DAH for NCDs remained very low, only increasing from 1% of total DAH in 1990 to 2% in 2022. Meanwhile, infectious diseases such as HIV/AIDS (26%), malaria (6.4%), and tuberculosis (3.5%) captured larger DAH allocations (2015 data) [5,66].

Moreover, DAH has been shown to underfund primary health care and HSS, with allocations for HSS declining from 19% in 1990 to just 7% in 2022 [5]. This reinforces vertical programming focused on specific diseases instead of cross-cutting systems functions, shifting national attention and resources toward areas prioritized by donors rather than the national health needs, including the rising burden of NCDs [65-69].

Vertical programs create incentives that can alter managerial attention and internal resource flows. Research on global health initiatives shows how parallel systems for reporting, supply chain management, and supervision can divert capacity away from health system functions not covered by donor funds. Studies describe that reporting cycles, performance frameworks, and earmarked budgets influence national planning cycles and create incentives privileging donor objectives over locally determined needs [57,70-74]. Taking lessons from these experiences, a recent study concluded that declining aid is an opportunity to integrate vertical programs within the health system [75].

Financial substitution further complicates the sustainability landscape. Empirical evidence shows that DAH inflows can reduce domestic public health expenditure [20,76-78]. For every $1 increase in DAH channeled to governments (DAHG), there was a $0.62 decrease in government health expenditure (GHE), indicating displacement of domestic health spending. A study estimated that between 1995 and 2010, displacement of government health expenditure due to DAHG reduced total government health spending by $152.8 billion (90% CI: 46.9 to 277.6 billion) and concluded that only about 38% of every $1 of DAHG is truly additional to domestic health spending [79]. This implies that governments reduce their own health spending when receiving DAH, limiting fiscal effort, political commitment, and sustainability. It exposes health financing to risks when donor funding declines, as governments do not fully replace lost aid with their own funds. Countries often manage multiple donor-specific reporting cycles, audits, and performance frameworks, each reflecting different institutional priorities. Evidence shows these fragmented structures increase administrative burden and impede coherent national planning. A study by Spicer and colleagues showed that fragmentation persists despite successive aid-effectiveness agreements, driven by divergent donor mandates, weak coordination mechanisms, and inconsistent compliance with alignment principles [25]. Such parallel systems can produce distortions in human resources, data systems, and governance architecture. For example, staff may be allocated preferentially to donor-prioritized areas with salary supplementation or additional incentives, leaving underfunded parts of the health system understaffed [80,81].

Power and agenda setting

The persistence of agenda distortion is rooted not only in technical misalignment but also in the power asymmetries that shape donor-recipient relationships. The ‘donor interest-recipient need’ framework [18] highlights how health priorities emerge through negotiated processes in which donors typically retain disproportionate influence because of their control over financial and technical resources. The exercise of power in this space can be studied using Lukes’ three dimensions of power [82,83]

1. The first dimension involves visible decision-making power:

Direct conditionalities, earmarking, and performance-based

funding mechanisms that explicitly shape program priorities.

2. The second dimension involves non-decision-making power,

where donors shape the agenda by controlling which issues

are considered or excluded from discussion, thereby preventing

certain health needs from reaching the policy table. This

hidden power limits the scope of national debates and sidelines

topics that do not align with donor priorities.

3. The third dimension reflects ideological power, where donors

influence the perceptions, beliefs, and preferences of

national stakeholders, leading countries to internalize donor

priorities as natural or inevitable. It involves the production

of norms, metrics, and expectations such as “global best practices”

or “evidence-based” interventions that align national

strategies with donor preferences.

Power in donor-recipient interactions can also be studied using Barnett and Duvall’s taxonomy of Power [39]:

• Compulsory power is the direct and observable control

donors exert by providing or withholding funding, technical assistance,

or sanctions, thereby compelling governments to adopt

specific health policies and priorities. This manifests in explicit

influence over decision-making and resource allocation.

• Institutional power is exercised through donors shaping

the rules, norms, and procedures within global and national

health governance structures, influencing which actors participate

and how decisions are made on health agenda-setting. This

indirect control creates lasting constraints on national policy options.

• Structural power lies in the underlying social and economic

arrangements that define the positions and capacities of

donor and recipient actors, such as the global aid architecture and

economic dependencies that position donors as indispensable

and shape recipient government behavior and interests.

• Productive power operates through discourses, knowledge

production, and framing mechanisms by which donors influence

what counts as legitimate health problems and appropriate

interventions, shaping national health narratives and the identities

of stakeholders to align with donor priorities.

These forms of power explain why agenda distortion persists even in contexts where aid-effectiveness norms promote ownership and alignment. Theoretical contributions from Lukes’ three-dimensional view of power and Barnett and Duvall’s taxonomy of power deepen understanding of how donor preferences are embedded within aid architectures. These dynamics manifest as preferential financing for interventions that align with donor mandates, privileging biomedical and quantifiable outcomes, and the diffusion of policy models that may not reflect domestic political or epidemiological contexts [84].

Aid-effectiveness frameworks and their limitations

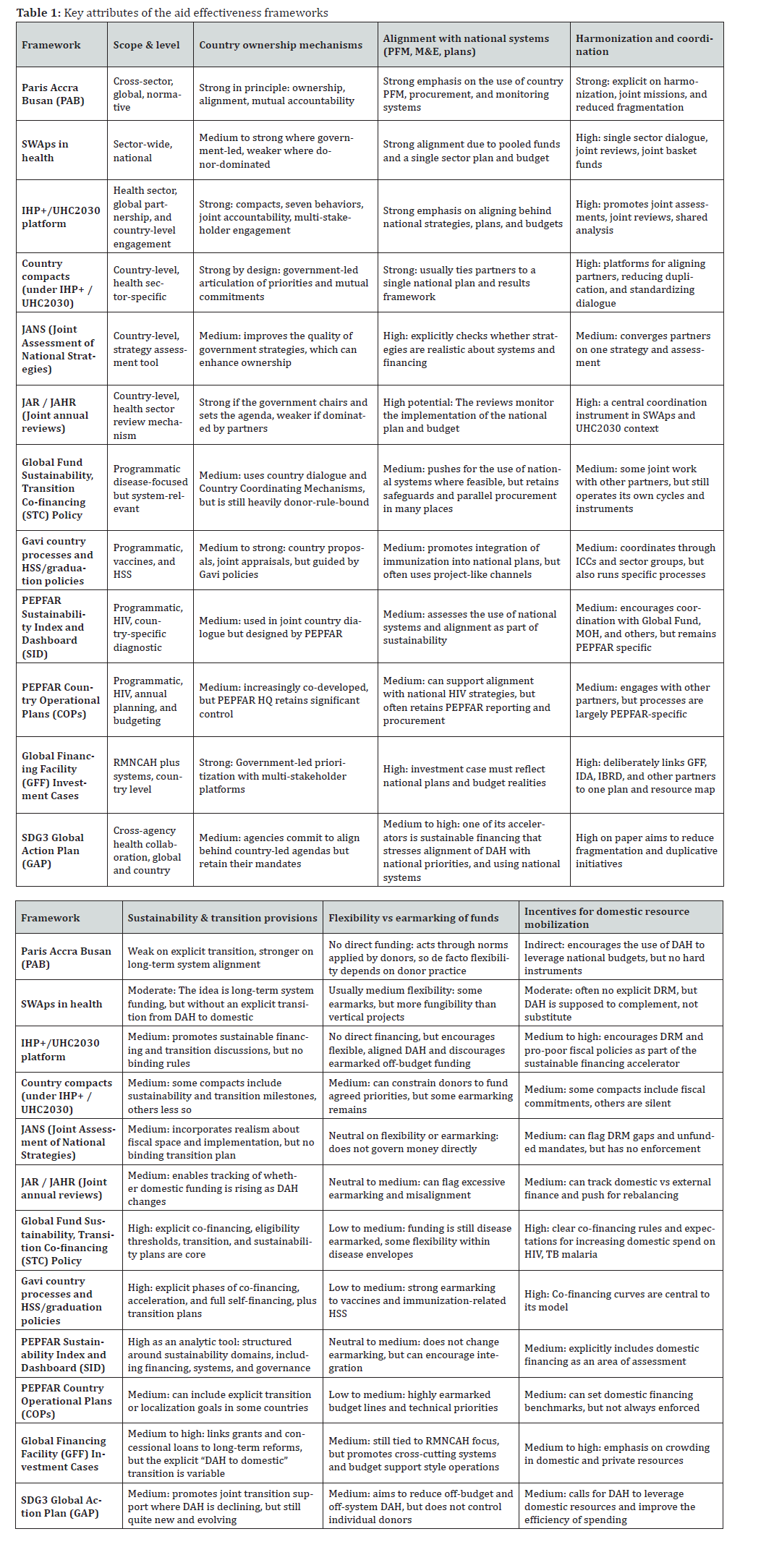

Aid-effectiveness frameworks have been discussed and launched over the years with an aim to correct some of the structural issues discussed above by recommitting donors to country ownership, alignment, and harmonization. UHC2030 operationalized these principles through the “seven behaviors,” emphasizing unified national plans and shared accountability frameworks [85]. Over just six years from 2005-2011, five aid effectiveness initiatives were launched: the Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness (2005) [29], the International Health Partnership plus (2007), the Accra Agenda for Action (2008) [30], the Busan Partnership for Effective Cooperation (2011) [31], and the Global Partnership for Effective Development Cooperation (GPEDC) (2011) [86]. More recently, in 2015, the Addis Ababa Action Agenda (AAAA) [87] was signed at the third international conference on financing for development, and the Universal Health Coverage (UHC) 2030 Global Compact was signed in 2017 [88]; see Table 1 for the key features of the selected aid effectiveness framework.

Empirical evaluations of aid effectiveness frameworks reveal persistent challenges in adherence to their recommendations, such as country ownership, alignment, harmonization, and mutual accountability. Studies demonstrate that donors often maintain parallel systems rather than fully integrating with recipient country systems, largely due to accountability pressures and mandate-driven priorities [89-92]. Some structural limitations and gaps in aid effectiveness frameworks and policies pronounce the effects of these factors on national agenda distortion, such as:

1. Weak enforceability: Principles of alignment and ownership

lack mandatory compliance mechanisms.

2. Fragmentation: Multiple donor-specific tools such as Gavi

transition criteria, Global Fund co-financing rules, and PEPFAR’s

Sustainability Index operate in parallel, producing

a proliferation of policy instruments rather than coherent

alignment.

3. Oversimplified technocratic solutions: Tools such as Joint

Assessments of National Health Strategies (JANS) or annual

health sector reviews emphasize procedural alignment but

often fail to address political determinants of priority setting.

4. Limited adaptation to changing donor landscape: The

frameworks were designed for bilateral and multilateral donors

but are less suited to the growing influence of private

philanthropic and non-state actors (NSA).

5. Insufficient incorporation of political economy analyses:

Most frameworks treat misalignment as a technical issue

rather than a manifestation of power asymmetries.

As DAH declines and transitions accelerate, these gaps become more apparent and increasingly important to bridge. Policy frameworks should be able to sustainably mitigate power asymmetries and structural dependency to prevent agenda distortion. The next section explores the policy gaps in aid effectiveness and transition frameworks in detail.

Policy Gaps in the Aid Effectiveness and Transition Frameworks

Despite the evolution of global aid-effectiveness and transition frameworks, several structural and functional gaps persist. Table 1 demonstrates the attributes of cross-sectoral compacts such as the Paris, Accra, and Busan agreements [29-31] institutionalized principles of ownership, alignment, and harmonization, yet in practice, they have been insufficient to counterbalance the stronger incentives for vertical, earmarked funding models. Evaluations consistently show that, despite donor accountability requirements to domestic constituencies, short funding cycles, and siloed program architectures, they continued to reproduce fragmentation and parallel systems [34-36]. As a result, the principles of “alignment” and “use of country systems” have not translated into donor practices. This creates a persistent implementation gap where normative commitments are not reflected in practiced behavior.

A second gap concerns the inability of both aid-effectiveness and transition frameworks to explicitly address the political economy of power imbalances that sustain agenda distortion. Neither the Paris-Accra-Busan agreements nor the UHC2030 mechanisms directly confront the structural incentives that drive donors to prioritize vertical programs, measurable short-term outputs, or geopolitical interests. Likewise, contemporary transition frameworks used by the Global Fund, Gavi, PEPFAR, or World Bank-affiliated mechanisms are heavily technocratic and focused on fiscal thresholds, co-financing ratios, or epidemiological benchmarks (summarized in Table 1).

They rarely consider how colonial legacies, institutional dependencies, or long-standing asymmetries in negotiation capacity shape priority-setting, even though evidence from Puerto Rico, Sri Lanka, Cambodia, and Botswana shows that structural dependence persists [34-37]. Transition tools often assess sustainability in terms of financial handover, not in terms of whether countries will be left with systems configured around donor legacies rather than national needs. This results in a narrow conception of transition that treats the process as a technical shift in financing rather than a political and institutional transformation requiring re-balancing of power and long-term system restructuring.

A third major gap is the limited attention to volatility, predictability, and long-term fiscal planning. Aid-effectiveness principles emphasize predictability, yet donors continue to implement abrupt funding changes and re-prioritize interventions. Furthermore, frameworks do not require donors to coordinate transition timelines or synchronize demands, resulting in cumulative shocks when multiple donors reduce support simultaneously.

Finally, neither set of frameworks adequately addresses the sustainability of health-system functions that donors themselves historically financed. Transition tools typically focus on HIV, TB, malaria, or immunization program sustainability but show limited engagement with supply chain integration, HRH absorption, laboratory networks, surveillance systems, or community-based services. These systems often lack a post-donor integration pathway, creating a transition risk that both aid-effectiveness and transition frameworks fail to address. The Cambodia Sustainability Roadmap, for instance, identified multi-layered dependencies in health information systems, procurement, and civil-society networks that require long-term domestic planning and technical restructuring rather than short-term handover [34].

Collectively, these gaps highlight the disconnect between the intended role of policy frameworks and their real-world effects. While the frameworks create a normative architecture of national ownership and sustainability, they lack the political, financial, and institutional mechanisms required to counterbalance donor incentives, correct historical asymmetries, or power imbalances. Addressing these gaps is essential for preventing agenda distortion and building nationally led, sustainable health financing ecosystems.

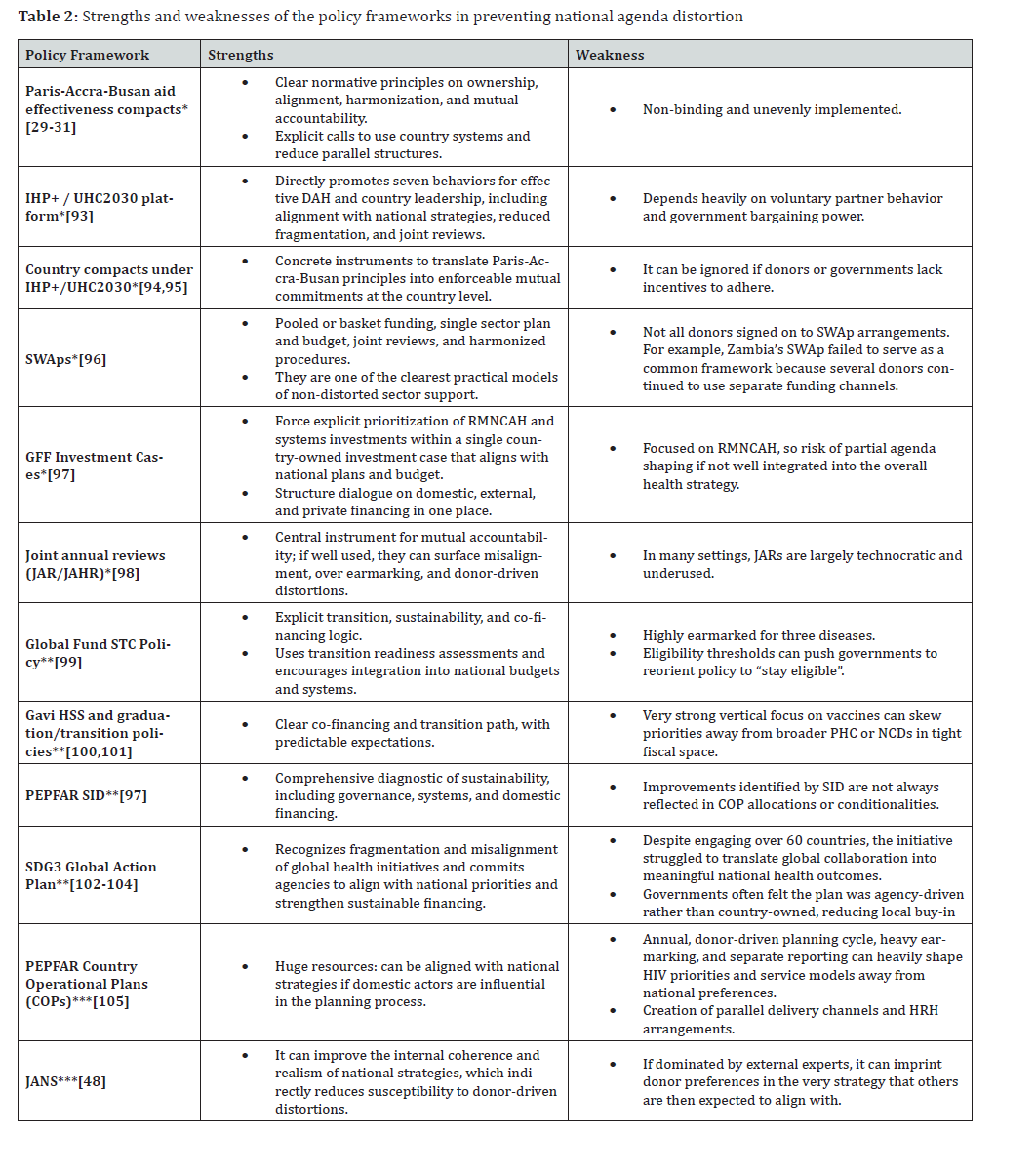

To make informed policy recommendations, Table 2 categorizes the key strengths and weaknesses of all the studied policy frameworks. However, evidence has shown that weak enforcement of their policy guidance has also been a key reason for suboptimal outcomes of these frameworks vis-à-vis their intended aims.

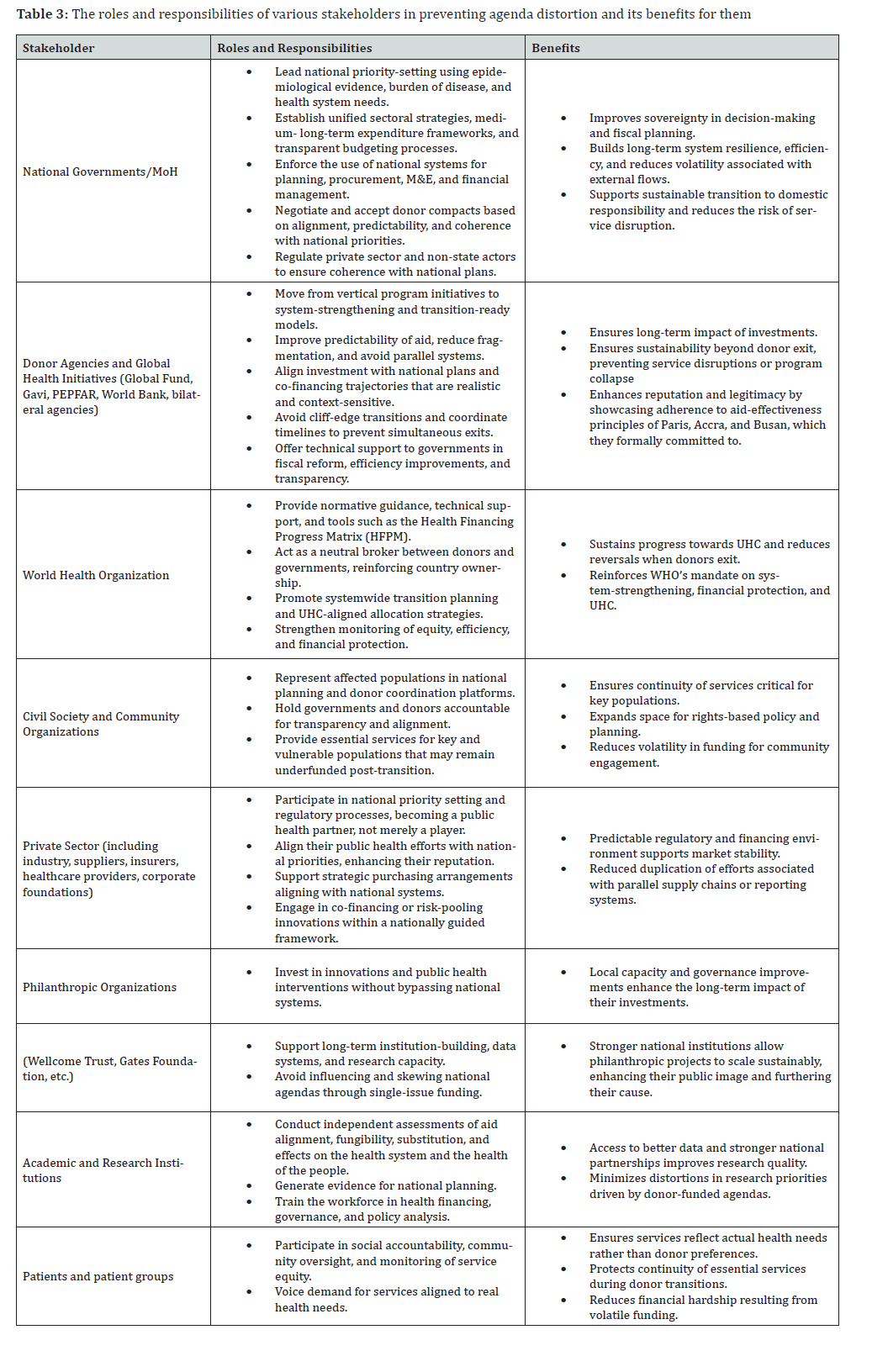

To illustrate how different actors could contribute to and gain from a more balanced policy process, Table 3 sets out the distinct roles and responsibilities of key stakeholders along with the benefits they experience when agenda distortion is avoided.

Policy Recommendations

Addressing the identified gaps requires a realignment of global and national policy instruments to shift from normative commitments toward enforceable, accountability-driven mechanisms that prioritize national autonomy, system strengthening, and sustainability. Table 3 lists the roles and responsibilities of various stakeholders and the benefits of preventing agenda distortion for them.

1. Governance and Aid Coordination

National Aid Coordination Office as Mandatory Single Gateway

Recipient countries should establish an Aid Coordination Office (ACO) with representation from the Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Finance, functioning as the mandatory entry point for all health financing negotiations with bilateral, multilateral, foundation, and private sector donors. This office would centralize the evaluation of all external financing proposals against the National Health Plan and the country’s epidemiological priorities, issuing binding opinions that enable the government to reject or request modifications to misaligned proposals. The ACO would operate through legal mandate, requiring donors to submit proposals with sufficient lead time and include alignment analysis with national priorities, integration plans with existing systems, and transition strategies. This mechanism strengthens the recipient country’s negotiating power and reduces the fragmentation that generates agenda distortion.

Official List of Top 10 National Public Health Priorities

Each country should publish and update annually an official list of the top 10 public health priorities based on disease burden, epidemiological analysis, and health system needs, developed jointly by the Ministry of Health and the WHO country office. This list becomes the mandatory reference standard against which all donor financing alignment is evaluated. The methodology for developing this list would integrate disease burden data (DALYs), mortality, health system capacity, and priorities expressed in national plans, published in a publicly accessible digital format with annual updates. Donors must demonstrate how their financing addresses at least one of the listed priorities, and the ACO uses this list as a central evaluation criterion. This explicit benchmark of needs makes it more difficult to impose external priorities misaligned with national epidemiological reality.

2. Long-Term Predictability and Financial Planning

Binding Multi-Year Financial Predictability Standards

Donors participating in pooled financing mechanisms or country compacts should publish binding multi-year financial commitments of at least 5 years, including projected annual amounts, phased reduction schedule, national co-financing expectations, and programmatic transition plan. A centralized platform under UHC2030 would register these commitments in a standardized format, allowing recipient countries to incorporate this information into their medium-term fiscal frameworks and multi-year budgets. Non-compliance with commitments without justification would generate graduated consequences: public reporting, financial penalties directed to the affected country’s transition fund, and eventual temporary suspension of eligibility for new multilateral agreements. This mechanism reduces DAH volatility that impedes long-term planning and enables governments to develop sustainable policies based on predictable flows.

Mandatory Phased Exit Planning from Financing Inception

All donor financing agreements should include, from their conception, an explicit phased exit plan with a clear timeline for domestic financial substitution, regardless of the country’s current income level. This plan would specify annual percentages of incremental co-financing by the recipient government, projected year of complete donor exit, and specific triggers (epidemiological and fiscal) for timeline adjustments. The recipient government would present annual evidence that projected budget increases are being executed, with analysis of additionality versus substitution through National Health Accounts. Plans would be reviewed every 2 years and could be adjusted under documented mutual consent. This approach corrects the problem of ad-hoc transition planning that generates sustainability crises when donors withdraw abruptly.

3. Systems Integration and Sustainable Transition

Comprehensive Health System Transition versus Programmatic Transition

Donor transition frameworks should expand from vertical programmatic criteria (disease elimination/control, fiscal thresholds) to a comprehensive evaluation of health system capacities to absorb functions historically financed by donors. “Transition readiness” would include mandatory assessment of capacities in procurement and supply chain, human resources, information and surveillance systems, laboratories, regulatory capacity, community networks, governance, and sustainable financing. A standardized Health System Transition Readiness Assessment would be conducted 3 years before the projected transition, identifying critical gaps requiring strengthening before exit. When this assessment identifies systemic weaknesses, the transition plan would include specific financing to strengthen capacities, and the timeline would adjust according to demonstrated progress. This approach recognizes that fiscal or epidemiological readiness does not guarantee system capacity to sustain functions autonomously.

Incentives for Country Systems Use and Penalties for Parallel Structures

Aid effectiveness principles should be operationalized through concrete financial incentives that link donor eligibility to participate in pooled financing mechanisms to demonstrated use of national procurement, budgeting, and information systems. Donors maintaining parallel structures without integration plans should face progressive disincentives, such as restrictions on access to multilateral funds or financial penalties directed to national system- strengthening funds. This approach would gradually realign financial flows toward national systems, reducing fragmentation and administrative burdens that perpetuate institutional dependencies and weaken domestic management capacities. Implementation would require mechanisms to verify effective use of country systems and clear criteria on when justified exceptions are admissible.

Domestic Fiscal Reform Commitments as Prerequisite for Aid Renewal

Recipient countries should demonstrate, as a condition for renewal of financing agreements, that they are implementing domestic fiscal reforms that increase fiscal space for health and that donor resources are truly additional and do not substitute national public spending. Each renewal would require evidence of a sustained increase in budgetary allocation to health, documented progress in eligible fiscal reforms (elimination of regressive subsidies, taxes on harmful products, improvements in tax collection, reduction of tax evasion), and an analysis in National Health Accounts demonstrating additionality. Countries demonstrating systematic substitution would face phased aid reduction until correcting the pattern, while those with proven additionality would receive timeline extensions or bonuses. This mechanism addresses the fungibility problem where DAH displaces domestic spending rather than supplementing it.

4. Accountability and Power Asymmetry Correction

Mandatory Integration of Political Economy Analysis in Aid Evaluations

All aid effectiveness tools (Joint Assessment of National Strategies, UHC2030 country compacts, co-financing reviews) and transition assessments should incorporate structured political economy analysis modules that identify power asymmetries, negotiation capacity, donor institutional incentives, and potential sources of agenda distortion. A standardized module based on HIPES methodology and power frameworks would be integrated as a mandatory section, including mapping of actors and institutional incentives, analysis of negotiation asymmetries, identification of structural power mechanisms, and evaluation of real versus nominal alignment. The analysis would be conducted by mixed teams (government, independent facilitator, civil society), and results would inform distortion risk mitigation plans incorporated into country compacts. This approach recognizes that misalignment is a product of political determinants and power asymmetries, not just technical miscoordination.

Public Donor Performance Ranking System

A global donor performance ranking system should be established, administered by an independent entity, that evaluates and publicly reports annual scores for each donor based on adherence to aid effectiveness principles, predictability, use of country systems, and track record of successful transitions. The methodology would evaluate donors across dimensions of alignment with national priorities, predictability of commitments, use of certified country systems, harmonization, sustainable transition track record, and transparency. Scores would be calculated using public data and surveys of recipient countries, published on an open-access platform. Countries would use these rankings as criteria to select and prioritize financing partners, while donors with poor performance would face reputational costs affecting their positioning. This mechanism generates incentives for donors to improve their aid effectiveness practices and strengthens recipient countries’ negotiating power.

*These frameworks are explicitly oriented to country ownership, alignment, and harmonization, and are not themselves highly earmarked financial

instruments; and have a high potential to prevent agenda distortion if implemented.

**These instruments are designed to manage transition and sustainability, but their vertical, disease, or intervention-specific nature carries inherent

risk of agenda distortion and hence, have medium potential to prevent agenda distortion.

***These frameworks can contribute to the prevention of agenda distortion if used well, but carry a significant risk of reinforcing distortions.

Binding Mutual Accountability Mechanisms

Mutual accountability should be operationalized through shared performance indicators, mandatory annual joint reviews, and linkage of compliance scores to financial allocation decisions by both parties. Each country compact would include a Mutual Accountability Framework establishing indicators for donors (predictability, alignment, use of country systems, harmonization) and governments (fiscal effort, implementation of reforms, transparency), with quantifiable annual targets and joint reviews facilitated by a neutral entity. Non-compliance would generate graduated consequences: public reporting, percentage withholding of next disbursements, and eventual full review of agreement terms. The scores would feed into the donor ranking and parliamentary reports on aid management. This enforcement mechanism converts normative accountability principles into operational commitments with real consequences for both parties.

Multi-Stakeholder Governance Platforms and Civil Society Sustainability

Countries should establish formal multi-stakeholder dialogue platforms that institutionalize the participation of civil society, patient organizations, medical societies, academia, the private sector, non-state actors, and donors in the planning, monitoring, and evaluation of health aid and transition processes. These platforms would operate as permanent consultation spaces linked to the ACO, with balanced representation of actors, clear advisory mandates on health needs prioritization, and the capacity to raise alerts about misalignments or sustainability risks. Special coordination mechanisms should be established for non-state actors and philanthropic organizations operating outside traditional bilateral/ multilateral architectures, requiring their alignment with national priorities and participation in accountability platforms. This mechanism expands the base of actors involved in aid governance beyond the donor-government dyad, incorporates perspectives of those who directly experience the effects of agenda distortion, and strengthens legitimacy and national ownership of health policies.

Conclusion

The current study demonstrates that while global aid-effectiveness agreements and donor transition frameworks were created to promote national ownership, alignment, and sustainability, they have been unable to counteract the structural incentives that continue to drive agenda distortion. Evidence across multiple countries shows that the principles articulated in Paris, Accra, and Busan remain aspirational because the donor financing landscape is dominated by vertical programs, short funding cycles, and parallel system requirements that often override national priorities. Transition frameworks developed by major global health initiatives have similarly focused on fiscal thresholds and program maturity while overlooking the political, institutional, and historical factors that embed long-term dependency. As countries approach transition in a period of declining development assistance for health, these gaps become even more visible, increasing risks to health system stability, governance, and the sustainability of health gains.

Addressing these challenges requires action from all stakeholders, as it is in their interest that health interventions in a country remain nationally led and population health-driven without any fragmentation and duplication of efforts. For this to happen, a decisive shift from normative statements toward enforceable mechanisms that strengthen country leadership, improve predictability of funds, and ensure donors participate in coordinated, system-wide planning is needed. Embedding political economy analysis, system integration requirements, and civil-society sustainability into policy frameworks is essential. Likewise, governments must advance fiscal reforms and strengthen institutions to absorb responsibilities historically managed through donor-funded architectures. In doing so, countries and donors can move toward health systems that are nationally steered, financially sustainable, and aligned with population health needs. The recommendations of this study highlight a practical path toward reshaping global aid governance in ways that minimize agenda distortion and help achieve the desired state: DAH should operate as a catalyst that strengthens nationally led health systems, aligns fully with epidemiological needs and national priorities, supports predictable financing to ensure long-term planning, and enables a smooth transition to sustainable self-reliance without distorting national agendas or creating long-term structural dependencies.

References

- Negeri KG, Haile mariam D (2016) Effect of health development assistance on health status in sub-Saharan Africa. Risk Management and Healthcare Policy 9: 33-42.

- Kwete XJ, Berhane Y, Mwanyika-Sando M, Oduola A, Liu Y, et al. (2021) Health priority-setting for official development assistance in low-income and middle-income countries: a Best Fit Framework Synthesis study with primary data from Ethiopia, Nigeria and Tanzania. BMC Public Health 21(1): 1-13.

- Li Z, Li M, Patton GC, Lu C (2018) Global Development Assistance for Adolescent Health From 2003 to 2015. JAMA Network Open 1(4): 1-13.

- Biesma RG, Brugha R, Harmer A, Walsh A, Spicer N, et al. (2009) The effects of global health initiatives on country health systems: a review of the evidence from HIV/AIDS control. Health Policy and Planning 24(4): 239-252.

- Xie S, Du S, Huang Y, Luo Y, Chen Y, et al. (2025) Evolution and effectiveness of bilateral and multilateral development assistance for health: a mixed-methods review of trends and strategic shifts (1990-2022). BMJ Global Health 10(1): 1-13.

- Fryatt RJ, Blecher M (2023) In with the good, out with the bad Investment standards for external funding of health? Health Policy OPEN 5: 1-6.

- Charlson FJ, Dieleman J, Singh L, Whiteford HA (2017) Donor Financing of Global Mental Health, 1995-2015: An Assessment of Trends, Channels, and Alignment with the Disease Burden. PLoS ONE 12(1): 1.

- Collins TE, Karapici A, Berlina D (2025) Investing in Addressing NCDs and Mental Health Conditions: a Political Choice. Annals of Global Health 91(1): 1-9.

- Samb B, Evans T, Dybul M, Atun R, Moatti JP, et al. (2009) An assessment of interactions between global health initiatives and country health systems. The Lancet 373(9681): 2137-2169.

- Bendavid E (2016) Past and Future Performance: PEPFAR in the Landscape of Foreign Aid for Health. Current HIV/AIDS Reports 13(5): 256-262.

- Brown GW, Rhodes N, Tacheva B, Loewenson R, Shahid M, et al. (2023) Challenges in international health financing and implications for the new pandemic fund. Globalization and Health 19(1): 1-16.

- Dieleman J, Campbell M, Chapin A, Eldrenkamp E, Fan VY, et al. (2017) Evolution and patterns of global health financing 1995-2014: Development assistance for health, and government, prepaid private, and out-of-pocket health spending in 184 countries. The Lancet 389(10083): 1981-2004.

- Khan MS, Meghani A, Liverani M, Roychowdhury I, Parkhurst J (2018) How do external donors influence national health policy processes? Experiences of domestic policy actors in Cambodia and Pakistan. Health Policy and Planning 33(2): 215-223.

- Dreher A, Lang V, Reinsberg B (2024) Aid effectiveness and donor motives. World Development, 176: 1-20.

- Kennedy J, Thakrar R (2025) Who’s leading WHO? A quantitative analysis of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation’s grants to WHO, 2000-2024. BMJ Global Health 10(10): 1-11.

- Gonzalez AR, Vignoli L, Mehto AK, Attwill A, Srivastava N, et al. (2025) Geopolitical Realignments and the Ongoing Evolution of the New World Order: Reassessing the Implications for Global Health. Juniper Online Journal of Public Health 10(2): 1-12.

- Attwill A, Mehto A, Ramly C, Gonzalez AR, Flomo J, et al. (2025) Recent Geopolitical Shifts and Their Implications for Global Health: A New World Order in The Making. Juniper Online Journal of Public Health 9(4): 1-13.

- Hennessy J, Mortimer D, Sweeney R, Woode ME (2023) Donor versus recipient preferences for aid allocation: A systematic review of stated-preference studies. Social Science & Medicine 334: 1-16.

- Buse K, Booth D, Murindwa G, Mwisongo A, Harmer A, et al. (2014) Donors and the Political Dimensions of Health Sector Reform: The Cases of Tanzania and Uganda.

- Lu C, Schneider MT, Gubbins P, Leach Kemon K, Jamison D, et al. (2010) Public financing of health in developing countries: a cross-national systematic analysis. The Lancet 375(9723): 1375-1387.

- Impact of Development Assistance for Health on Country Government Spending. Institute For Health Metrics and Evaluation Pp: 1-4.

- Morrissey O (2015) Aid and Government Fiscal Behavior: Assessing Recent Evidence. World Development 69: 98-105.

- Dieleman J, Campbell M, Chapin A, Eldrenkamp E, Fan VY, et al. (2017) Evolution and patterns of global health financing 1995-2014: Development assistance for health, and government, prepaid private, and out-of-pocket health spending in 184 countries. The Lancet 389(10083): 1981-2004.

- Sundewall J, Forsberg BC, Jönsson K, Chansa C, Tomson G (2009) The Paris Declaration in practice: challenges of health sector aid coordination at the district level in Zambia. Health Research Policy and Systems 7(14): 1-10.

- Spicer N, Agyepong I, Ottersen T, Jahn A, Ooms G (2020) ‘It’s far too complicated’: why fragmentation persists in global health. Globalization and Health 16(1): 1-16.

- MacPherson P, Nliwasa M, Choko AT (2025) Reductions in development assistance for health funding threaten decades of progress in Africa. PLOS Medicine 22(8): 1-3

- Molaro M, Revill P, Chalkley M, Mohan S, Mangal TD, et al. (2025) The potential impact of declining development assistance for health on population health in Malawi: A modelling study. PLOS Medicine 22(8): 1-14.

- MacPherson P, Nliwasa M, Choko AT (2025) Reductions in development assistance for health funding threaten decades of progress in Africa. PLOS Medicine 22(8): 1-3.

- Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness (2005) Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness Pp: 1-16.

- Accra Agenda for Action (2008) Accra Agenda for Action Pp: 1-10.

- Busan Partnership for Effective Development Co-Operation (2011) Fourth High Level Forum on Aid Effectiveness, Busan, Republic of Korea Pp: 1-12.

- Country compacts-UHC2030.

- Alignment initiatives-UHC2030. Supporting the Lusaka Agenda.

- Towards Ending Aids in Cambodia Sustainability Roadmap.

- UNAIDS (2020) Readiness Assessment for transition and sustainability planning for Sri Lanka’s AIDS response Transition Readiness Assessment Report Pp: 1-96.

- BOTSWANA: Sustainability and Transition Readiness Assessment and Roadmap for HIV and TB (2024) Pp: 1-90.

- Gonzalez A R (2025) Colonialism, Dependency, and Health Trajectories: An Integrative Analysis of Historical Trends, Epidemiology, and Policy Analysis in Puerto Rico between 1898-1969. Juniper Online Journal of Public Health 10(2): 1-12.

- Tim Brown, Susan Craddock, Alan Ingram (2012.) Critical Interventions in Global Health: Governmentality, Risk, and Assemblage. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 102(5).

- Barnett M, Duvall R (2005) Power in International Politics. Source: International Organization 59(1): 39-75.

- Huffstetler HE, Bandara S, Bharali I, Kennedy Mcdade K, Mao W, et al. (2022) The impacts of donor transitions on health systems in middle-income countries: a scoping review. Health Policy and Planning 37(9): 1188-1202.

- Mao W, McDade KK, Huffstetler HE, Dodoo J, Abankwah DNY, et al. (2021) Transitioning from donor aid for health: perspectives of national stakeholders in Ghana. BMJ Global Health 6(1): 1-9.

- Perlman S, Ben Sheleg E, Ellen ME (2025) Making sense of conducting a critical interpretive synthesis: A scoping review. Research Synthesis Methods 00: 1-12.

- Dowding K (2006) Three-dimensional power: A discussion of Steven Lukes’ power: A radical view. Political Studies Review 4(2): 136-145.

- Sustainability, Transition and Co-Financing-The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria.

- GAVI (2025) Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance Eligibility and Transition Policy Pp: 1-5.

- Ocampo MS (2018) Determining Sustainability Factors in PEPFAR-Sponsored Programs and Products Transitioned to Local Ownership Pp: 1-30.

- (2020) Protecting and promoting and accelerating Health Gains for Women, Children and Adolescents. Global Financing Facility 2021-2025 Strategy.

- IHP (2015) Joint Assessment of National Health Strategies and Plans (JANS).

- WHO (2025) WHA78.12: Strengthening health financing globally.

- The Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness and the Accra Agenda for Action (2008).

- Cometto G, Ooms G, Starrs A, Zeitz P (2009) A global fund for the health MDGs? The Lancet 373(9674): 1500-1502.

- The Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness: Donor Commitments and Civil Society Critiques (2007).

- Lars Engberg-Pedersen (2011) Are Horizontal Partnerships the key to move the Paris Declaration forward in Busan?

- Better Aid (2012) Aid Effectiveness 2011 Progress in Implementing the Paris Declaration Pp: 1-204.

- United Nations (2011) Enhancing aid effectiveness: From Paris to Busan.

- Lindsay Whitfield (2008) The Politics of Aid: African Strategies for Dealing with Donors. The Politics of Aid.

- Sridhar D, Tamashiro T (2009) Vertical funds in the health sector: lessons for education from the Global Fund and GAVI. United Nations Pp: 1-45.

- Bendavid E, Ottersen T, Peilong L, Nugent R, Padian N, et al. (2017) Development Assistance for Health. Disease Control Priorities, Third Edition (Volume 9): Improving Health and Reducing Poverty: 297-313.

- Overview of development assistance for health trends. Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation Pp: 1-7.

- Nonvignon J, Soucat A, Ofori-Adu P, Adeyi O (2024) Making development assistance work for Africa: from aid-dependent disease control to the new public health order. Health Policy and Planning 39(Suppl 1): 79-92.

- Apeagyei AE, Bisignano C, Elliott H, Hay SI, Lidral Porter B, et al. (2025) Tracking development assistance for health, 1990-2030: historical trends, recent cuts, and outlook. Lancet (London, England) 406(10501).

- Angela Owiti (2017) Global Health Initiatives: What Do We Know About Their Impact on Health Systems? PEAH-Policies for Equitable Access to Health.

- Patel P, Cummings R, Roberts B (2015) Exploring the influence of the Global Fund and the GAVI Alliance on health systems in conflict-affected countries. Conflict and Health 9(1): 1-9.

- Lesego A, Were LPO, Tsegaye T, Idris R, Morrison L, et al. (2024) Health system lessons from the global fund-supported procurement and supply chain investments in Zimbabwe: a mixed methods study. BMC Health Services Research 24(1): 1-13.

- Kim S, Tadesse E, Jin Y, Cha S (2022) Association between Development Assistance for Health and Disease Burden: A Longitudinal Analysis on Official Development Assistance for HIV/AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria in 2005-2017. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19(21): 1-12.

- Voigt K, King NB (2017) Out of Alignment? Limitations of the Global Burden of Disease in Assessing the Allocation of Global Health Aid. Public Health Ethics 10(3): 244-256.

- Shi J, Jin Y, Zheng Z (2023) Addressing global health challenges requires harmonized and innovative approaches to the development assistance for health. BMJ Global Health 8(5): 1-4.

- Bendavid E, Duong A, Sagan C, Raikes G (2015) Health Aid is Allocated Efficiently, but not Optimally: Insights from a review of Cost-Effectiveness Studies. Health Affairs (Project Hope) 34(7).

- Dieleman JL, Graves CM, Templin T, Johnson E, Baral R, et al. (2014) Global health development assistance remained steady in 2013 but did not align with recipients’ disease burden. Health Affairs (Project Hope) 33(5): 878-886.

- Regan L, Wilson D, Chalkidou K, Chi YL (2021) The journey to UHC: how well are vertical programmes integrated in the health benefits package? A scoping review. BMJ Global Health 6(8): 1-11.

- Amanda Glassman, Lydia Regan, Y Ling Chi, Kalipso Chalkidou (2020) Getting to Convergence: How “Vertical” Health Programs Add Up to A Health System. Center for Global Development.

- Mussa AH, Pfeiffer J, Gloyd SS, Sherr K (2013) Vertical funding, non-governmental organizations, and health system strengthening: perspectives of public sector health workers in Mozambique. Human Resources for Health 11(1): 1-9.

- Chaitkin M, Blanchet N, Su Y, Husband R, Moon P, et al. (2018) Integrating Vertical Programs into Primary Health Care.

- Integrating Vertical Programs into Primary Health Care Pp: 1-4.

- Mao W, McDade KK, Huffstetler HE, Dodoo J, Abankwah DNY, et al. (2021) Transitioning from donor aid for health: perspectives of national stakeholders in Ghana. BMJ Global Health 6(1): 1-9.

- Batniji R, Bendavid E (2013) Considerations in Assessing the Evidence and Implications of Aid Displacement from the Health Sector. PLoS Medicine 10(1): 1-2.

- Drake T, Regan L, Baker P (2023) Reimagining Global Health Financing How Refocusing Health Aid at the Margin Could Strengthen Health Systems and Futureproof Aid Financial Flows. Center for Global Development Pp: 1-26.

- Farag M, Nandakumar AK, Wallack SS, Gaumer G, Hodgkin D (2009) Does Funding from donors displace government spending for health in developing countries? Health Affairs (Project Hope), 28(4): 1045-1055.

- Dieleman JL, Hanlon M (2013) Measuring the Displacement and Replacement of Government Health Expenditure. Health Economics 23(2): 129-140.

- Vujicic M, Weber SE, Nikolic IA, Atun R, Kumar R (2012) An analysis of GAVI, the Global Fund and World Bank support for human resources for health in developing countries. Health Policy and Planning 27(8): 649-657.

- Cailhol J, Craveiro I, Madede T, Makoa E, Mathole T, et al. (2013) Analysis of human resources for health strategies and policies in 5 countries in Sub-Saharan Africa, in response to GFATM and PEPFAR-funded HIV-activities. Globalization and Health 9(1): 1-14.

- R Clegg S (1989) Frameworks of Power. SAGE Publications Ltd Pp: 1-66.

- Gaventa J (2006) Finding the spaces for change: A power analysis. IDS Bulletin 37(6): 23-33.

- Berlan D, Buse K, Shiffman J, Tanaka S (2014) The bit in the middle: a synthesis of global health literature on policy formulation and adoption. Health Policy and Planning 29(suppl 3): 23-34.

- Hammonds R, Ooms G, Mulumba M, Maleche A (2019) UHC2030’s Contributions to Global Health Governance that Advance the Right to Health Care: A Preliminary Assessment. Health and Human Rights 21(2): 235-249.

- Who We Are. Global Partnership for Effective Development Co-operation.

- Financing for Sustainable Development.

- Global Compact UHC2030.

- Haque H, Hill PC, Gauld R (2017) Aid effectiveness and programmatic effectiveness: a proposed framework for comparative evaluation of different aid interventions in a particular health system. Global Health Research and Policy 2(1): 1-7.

- Gulrajani N (2013) Organising for donor effectiveness: an analytical framework for improving aid effectiveness policies. Development Policy Review 32(1): 89-112.

- Ogbuoji O, Yamey G (2018) Aid Effectiveness in the Sustainable Development Goals Era. International Journal of Health Policy and Management 8(3): 184-186.

- Wickremasinghe D, Gautham M, Umar N, Berhanu D, Schellenberg J, et al. (2018) “It’s About the Idea Hitting the Bull’s Eye”: How Aid Effectiveness Can Catalyse the Scale-up of Health Innovations. International Journal of Health Policy and Management 7(8): 718-727.

- History UHC2030.

- Country compacts-UHC2030.

- IHP+ (2013) Development of a Country Compact: Guidance Note.

- Peters DH, Paina L, Schleimann F (2013) Sector-wide approaches (SWAps) in health: what have we learned? Health Policy and Planning 28(8): 884-890.

- Jennifer Kates, Kellie Moss, Stephanie Oum, Anna Rouw, Allyala Nandakumar (2023) Sustainability Readiness in PEPFAR Countries. KFF.

- (2014) Joint Annual Health Sector Reviews: Why and how to organize them.

- Sustainability, Transition and Co-Financing - The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria.

- Kenney C, Glassman A (2019) Gavi’s Approach to Health Systems Strengthening. Centre for Global Development Pp: 1-12.

- GAVI (2025) Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance Eligibility and Transition Policy.

- The Global Action Plan for Healthy Lives and Well-being for All.

- UNAIDS (2024) Joint Evaluation of the Global Action Plan for Healthy Lives and Well-being for All (SDG 3 GAP).

- Foreword (2024) progress report on the Global Action Plan for Healthy Lives and Well-being for All. Aligning for country impact Pp: 1-72.

- (2023) Country and Regional Operational Plans-United States Department of State.