Transparency, Partnerships and Coordination: Key Enablers for Control of An Outbreak of Acute Watery Diarrhoeal Disease (AWD) in the Sudan

Hassan El Mahdi El Bushra*1, Ayana Yeneabat1, Betigel W Habtewold2, Osman H Bilail3 and Naeema Al-Gasseer4

1Consultant Medical Epidemiologist, Sudan

2 Sub-National Health Cluster Coordinator, Health Cluster Support Project Sudan, World Health Organization, Sudan

3 Public Health and Community Medicine Consultant, Sudan

4 World Health Organization, Country Representative, Sudan Country Office, Sudan

Submission: August 08, 2018; Published: August 23, 2018

*Corresponding author: Hassan E El Bushra, Consultant Medical Epidemiologist, C/o World Health Organization, PO Box 2234 Khartoum, Sudan.

How to cite this article: Hassan El Mahdi El Bushra, Ayana Yeneabat, Betigel W Habtewold, Osman H Bilail, Naeema Al-Gasseer. Transparency, Partnerships and Coordination: Key Enablers for Control of An Outbreak of Acute Watery Diarrhoeal Disease (AWD) in the Sudan. JOJ Pub Health. 2018;4(1): 555630. DOI: 10.19080/JOJPH.2018.04.555630

Abstract

Background: A major outbreak of Acute Watery Diarrhoea (AWD) with high case-fatality ratio (CFR%) spread all over the Sudan occurred in 2016-2018. The aim of this paper is to describe the role transparency, partnerships and coordination as enablers for control of the AWD outbreak.

w up in hospitals in Gamo Gofa Zone.Method:269 high-level decision-makers in the country were interviewed using detailed standardized tools with open-ended questions. We conducted in-depth qualitative review of thematic and intervention areas; developed definitions and indicators based on published reports to assess some high–level enablers; transparency; and coordination and partnerships during outbreaks.

Result: The FMOH was not transparent during Phase I of the outbreak; there was relative but inadequate transparency during the Phase II of the outbreak. The FMOH fostered partnership with key national and international partners to augment its capacities and expedite response activities. Partners included key public sectors, NGOs, UN Agencies, and Community-Based Organizations (CBOs). The community participation and involvement improved during Phase II of the outbreak. Donors and UN agencies supported response activities as they reprogrammed some ongoing activities to secure funds. The high-level coordination mechanism resulted in mobilization of additional funding, expertise and medical supplies needed for surge capacity in response to the outbreak. The FMOH activated coordination platforms (e.g. EOC, taskforces and clusters) where partners convened and worked together. Similar fora were established at State levels..

Discussion:With timely and adequate transparency, FMOH could have contained the outbreak in a relatively shorter period, strengthened epidemiological and laboratory capacities, generated funds; and overcome challenges in bringing together different sectors (WASH and health) and actors (partner agencies) to the desired level of engagement.

Conclusion: Clear division of roles and responsibilities of partners would expedite successful containment of outbreaks within shorter periods.

Keywords: Acute Watery Diarrhea; Outbreak;Transparency;Partnerships;Coordination; Sudan

Abbrevations: ARC: American Refugee Committee; AWD: Acute Watery Diarrhea; CBOs: Community-Based Organizations; CBS: Community-Based Surveillance; CFR%: Case-Fatality Rate Percent; CSOs: Civil Society Organizations; DGEHA: General Directorate for Emergency, Emergency Humanitarian Action; DGs: Director Generals; EOC: Emergency Operation Center; EMRO: Eastern Mediterranean Regional Office; EWARS: Early Warning and Response System; FGDs: Focus Group Discussions; FMOH: Federal Ministry of Health; FRC: Free Residual Chlorine; HAC: Humanitarian Aid Commission; IDP: Internal Displaced Population; IHR: International Health Regulations 2005; IW: International Week; KI: Key Informants; MOF: Ministry of Finance; MOWR: Ministry of Water Resources; MSF: Médecins Sans Frontières; NGOs: Non-Governmental Organizations; NPHL: National Public Health Laboratory; NPP: National Preparedness Plan; NPRP: Preparedness and Response Plan; OD: Open Defecation; ODF: Open Defecation Free; PHEIC: Public Health Emergency of International Concern; RDT: Rapid Diagnostic Test; RRT: Rapid Response Team; SHF: Sudan Humanitarian Fund; SPHL: State Public Health Laboratories; SRCS: Sudanese Red Crescent Society; TCs: Treatment Centers; TOR: Terms of Reference; WHO: World Health Organization; UNICEF: United Nations Children Fund; UNDP: United Nations Development Program; UNOCHA: United Nations Office for Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs

Introduction

During outbreaks or other public health emergencies there is need to coordinate response activities among partners, expedite mobilization of resources, avoid duplication thereby saving time and leverage resources. Transparency during outbreaks provides individuals and communities with information needed to survive an emergency and decision-makers with crucial data needed for decision-making and priority setting. It is necessary, if not sufficient, condition for accountable decision-making and for the promotion of public trust, building multisector partnerships, leveraging of public health resources, communication, planning, and successful implementation of coordinated responses during outbreaks [1]. There are published reports that demonstrated the positive association between proactive risk communication in disseminating public health information, alleviating high levels of public concern, and anxieties; and the effectiveness of collaboration during implementation of collective response activities [2]. Coordination and collaboration of key partners in planning and adoption of protocols, identification of the roles and responsibilities, adequate training, equipping and preparing manpower to perform their roles help maximize utilization of resources during emergencies [3]. During the period between August 2016 and April 2017, an outbreak of Acute Watery Diarrhoea (AWD) spread all over the Sudan. An Inter- Ministerial Committee (IMC) led coordination of the activities of task-force committees at State and locality levels and helped mobilize resources. The aim of this paper is to describe the role transparency, partnerships and coordination as enablers for control of an outbreak of Acute Watery Diarrhoeal Disease (AWD) in the Sudan.

Material and Methods

The investigators divided the period of the outbreak into two phases: Phase I and Phase II; the date of establishment of the IMCs was used to mark the transition point for the two phases. We developed definitions and indicators based on published reports to assess high-level issues; and used analysis matrices to minimize subjectivity and increase objectivity of assessing transparency, partnerships and coordination of intervention activities during the AWD outbreak. Transparency is defined as proactive dissemination of risk-related information during management of public health emergencies [4]. Partnership during management of outbreaks is used to refer to close cooperation with one or more parties based on joint rights and responsibilities, whereas collaboration involves cooperation in which parties are not necessarily bound contractually. Coordination refers to the organization of the different partners involved in response activities related to management of a public health emergency to enable them to work together smoothly, efficiently and effectively. Coordination entails the ability to organize different response activities of a diverse group of stakeholders to enable them to work together smoothly, effectively, and efficiently. Collaboration effectiveness is defined as joint efforts to improve quality of service provision, cost savings, and coordination [5].

We discussed and evaluated some high–level enablers such as political will and leadership, resilience of the health system, transparency; and coordination and partnerships during outbreaks. We conducted in-depth qualitative review of thematic and intervention areas; e.g., surveillance, case management, Environmental health, health promotion, supplies and logistics. A limited summary of basic surveillance data was obtained from the Federal Ministry of Health (FMOH). We used detailed, adapted standardized tools to interview and conduct Focus Group Discussion (FGD) with a total of 269 high-level policy or decision-makers. We interviewed the Minister, Federal Ministry of Health (FMOH), State Minister of Ministry of International Cooperation, five State Ministers of Health, the Undersecretary of FMOH, and States Ministries of Health, Federal DGs for Planning, Emergency Humanitarian Affairs (EHA), National Health Insurance, Curative Medicine, States’ DGs, Coordinators, Program Officers, Task Force and Rapid Response Teams (RRT) members; DGs for Water Resources; Education, Humanitarian Action Commission (HAC), media (Radio and TV) and FMOH Advisory Group Members. Also, the IET interviewed Parliamentarians (Deputy Chair and Members of Health Committee of the National Assembly), Country Representatives for UN agencies (WHO, UNICEF, Resident Coordinator (UNDP), and UNOCHA) and Heads of Sub-offices for UNICEF, UNHCR, WHO in some States. The IET interviewed selected International Non-Governmental Organizations (INGOs), the Italian Cooperation, MSF Spain, SRCS, OXFAM, ARC, CARE. The IET conducted Focus Group Discussions (FGD), with Task Force members, RRT, EHA, Surveillance, Health Promotion and Environmental Health, healthcare workers at Treatment Centres and community members in charge of civil and societal organization (CBOs and CSOs), technical officers in Health and WASH Clusters and Water Resources. We made field visits to six States, Water Treatment Plants, water tankers, wells, etc., AWD Treatment Centres at Hospitals and Health Centres, and reviewed data on laboratory testing of water

Results

By the end of one year, the outbreak of AWD spread to 11 States; and the FMOH solicited support; the Cabinet created Inter-Ministerial Committees (IMC) of different compositions. Later, the AWD cases were reported from all States (36,962 AWD cases, including 823 deaths (Crude case-fatality rate percent [CFR%] = 2.2%). The FMOH fostered partnership with key national and international partners to augment its national capacities and expedite response activities. Soon after the detection of AWD outbreak, the FMOH activated a Taskforce within the Ministry only; meanwhile, the Cabinet of different States established Taskforce committees in their respective States that involved different ministries, commissioners, senior officials and partners. At a later stage of the outbreak, the Federal Government established IMCs at the federal level with involvement of selected partners in one of these committees (WHO). During Phase II of the outbreak, the FMOH activated coordination platforms (e.g. EOC, taskforces and clusters) where partners convened and worked together. Similar fora were established at State levels. Partners included key public sectors, NGOs, UN Agencies, and Community-Based Organizations (CBOs). During these meetings, the FMOH presented updates on the distribution of newly reported cases, the progress in instituting control measures in the different States, challenges or constraints and proposed solutions. Also, the FMOH held daily press meetings and shared some of the epidemiologic data as well as wide distribution of health education and messages to the public, among others. The FMOH did not disclose the causative organism of the current AWD outbreak. At a community level, local leadership often organized discussion fora which directed community level efforts. Donors and UN agencies reprogrammed some ongoing activities to secure funds. On Fridays, religious leaders advised the public on AWD prevention and control; and addressed rumours and misbelief about use of chlorinated water. The high-level coordination mechanism mobilized funds, expertise and additional medical supplies needed for surge capacity in response to the outbreak.

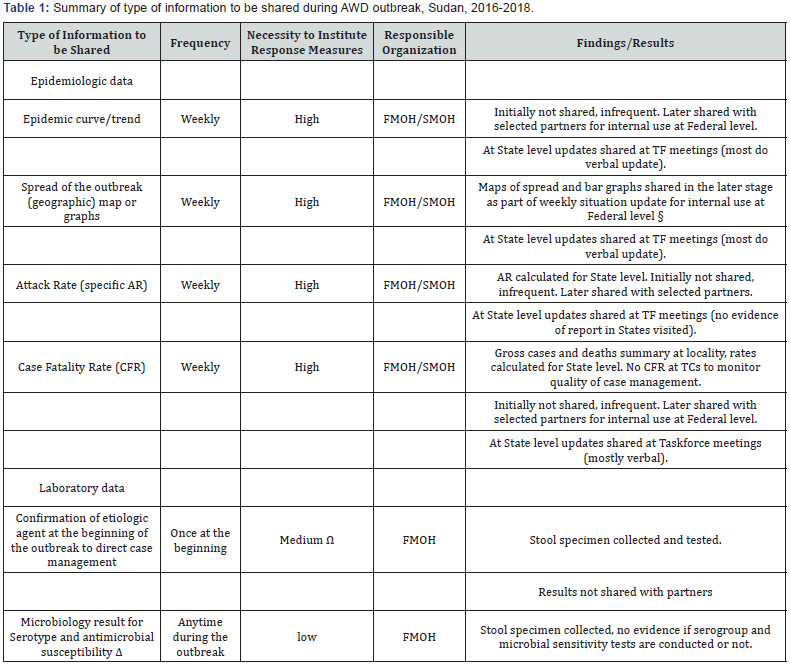

Table 1 summarizes the types of information to be shared during AWD outbreak, frequency of sharing information, necessity to institute response measures and responsible organization. The epidemiologic data includes epidemic curves or trends, spread of the outbreak (geographic) map or graphs, attack Rate (specific AR) and Case Fatality Rate (CFR). Laboratory data include Confirmation of etiologic agent at the beginning of the outbreak to direct case management, Microbiology result for Serotype and antimicrobial susceptibility Δ

§ Source: Federal Ministry of Health, AWD Update

Ω Clinical presentation, mode of transmission, and water quality test results (coliform count) can be used to initiate response actions. However, confirming the etiologic agent is useful to manage severs cases with appropriate antibiotics, to minimize the risk of drug resistance, and before using the IHR annex 2 instruments.

Δ Results can inform decision on type of antibiotic if recommended in case management (or review treatment protocol).

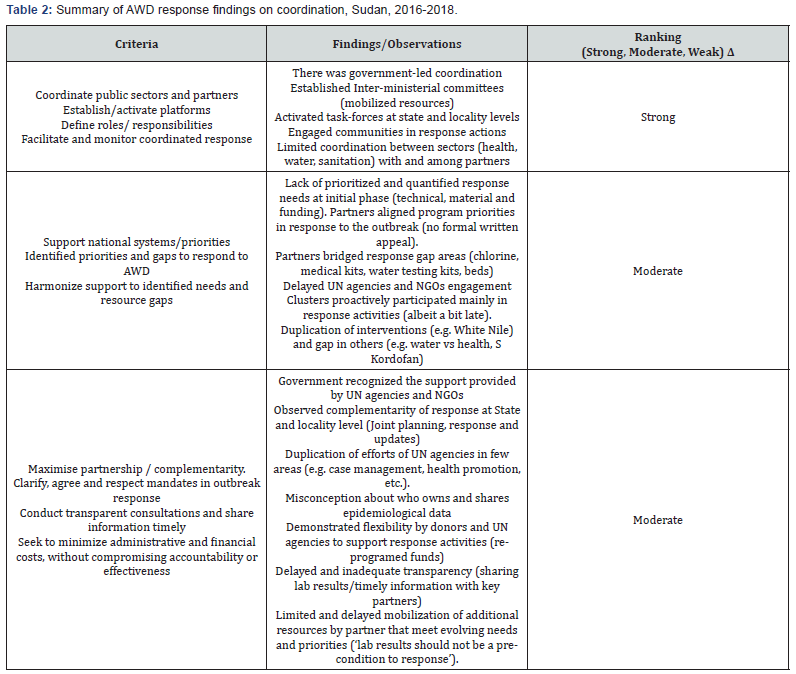

Table 2Summary of AWD response findings on coordination, Sudan, 2016-2018 summarizes the finding based on certain criteria Coordinate public sectors and partners, Establish/ activate platforms, Define roles/ responsibilities, Facilitate and monitor coordinated response, Support national systems/ priorities, Identified priorities and gaps to respond to AWD, Harmonize support to identified needs and resource gaps, Maximise partnership / complementarity. Clarify, agree and respect mandates in outbreak response,Conduct transparent consultations and share information timely, Seek to minimize administrative and financial costs, without compromising accountability or effectiveness

ΔHigh: Demonstrated or exceeded expectations of the corresponding criterion.

Medium: Demonstrated many corresponding criteria.

Low: Demonstrated a few or none of the expected criterion.

Discussion

Unlike activities of FMOH during Phase I of the AWD outbreak, the level of transparency increased significantly after establishment of the IMCs, Phase II of the outbreak. Inadequate transparency, irregular updates on pattern of spread of AWD, delays in sharing of information; especially and failure of the FMOH to disclose the causative organism of the AWD outbreak during Phase I, contributed to prolonged duration of the outbreak. Partners e.g., water department, needed access to updated real-time information sharing which was critical to ensure implementation of coordinated control measures effectively. Then, unaffected States lost lead time to mobilize resources and be better prepared for response activities and educate the public on preventive measures against the disease because the tendency of the FMOH to withhold information and not to share it in a real-time manner. It has been difficult to explain the tendency of the FMOH not to be transparent during this outbreak. It is conceivable that transparency during public health emergencies can result in collateral damages, such as economic losses to other sectors. Countries are often reluctant to openly declare an outbreak of an infectious disease for fear of economic sanctions related to travel and trade. But, historically, the FMOH has been fully transparent in more difficult and complex outbreaks such as Rift Valley Fever (RFV) in 2007 [6] Yellow Fever (YF) in 2012 and 2013 [7-9] and Ebola in 1976, 1979 and 2004 [10-12] meningococcal meningitis [13,14] and poliomyelitis [15,16] Understandably, during the initial phase of an AWD outbreak, scarcity of information could be a barrier for open communication. Lack or inadequate transparency would raise questions about the competency of the laboratory surveillance in the country as well as the credibility of the disease surveillance system in general and the competence of the national authorities to implement the International Health regulations, 2005 [17]. In the meantime, the rapidly wide spread of AWD in the country reflected weakness in the health system and delivering social services including access to potable water and functional latrines. However, it is always prudent to balance and adjust the depth and timing of information-sharing with rapid assessment of the situation and possible unfolding scenarios.

In the past many countries with similar outbreak of AWD had opted not to report such outbreak to WHO and the international community. Reluctance of the FMOH to announce a potential health threat and inform an at-risk population of appropriate precautionary measures, made constructive engagement of potential partners in coordinated public communication difficult [1] Although sharing of information on the AWD outbreak with domestic and international partners started relatively late, the intra- and inter-sectoral collaboration and concerted interventions improved and were instrumental in implementing and scaling up coordinated response activities; and offered clinicians, researchers an opportunity to learn from the outbreak. Successful partnership brought together a group of stakeholders, amplified their aligned contributions and support during the AWD outbreak. Yet, there were challenges in bringing together different sectors (WASH and health) and actors (partner agencies) to the desired level of engagement. This has led in some instances to duplicate efforts (same intervention in same locality by different agencies), and in others gaps in interventions and resources (health vs water sector; focus on water and not on latrine construction and use). However, the response to under-served populations (e.g. gold miners, migrant workers and nomads) remained in need for targeted strategies as well as innovative coordination mechanisms with other partners. Concerted efforts provided timely guidance to contain the fast evolving AWD outbreak; contributed in mobilizing grassroot communities and structures such as schools, religious leaders, CSOs, women and youth groups. Ideally, coordination should adhere to six core functions including support to service delivery, informing strategic decision making, planning and implementing strategies, monitoring performance and advocacy along with building national capacity in preparedness and response (IASC 2015) [18,19].

Definitions and levels of transparency and risk communication may vary; and its assessments may be subjective. Risk communication is vital and paramount in creation of partnerships. Timeliness, comprehensiveness and openness of information about outbreaks are important to handle unfounded rumours and rally public support in favour of control measures. This could lead to rumours and fast-spread of unsubstantiated information with unwarranted interference in travel and trade. Where transparent and forthcoming information is not shared regularly by relevant authorities, social media and other alternative sources of information are likely to influence the real picture of an event. This could lead to misrepresentation of the real picture thereby making it difficult to redress the damage done by rumours. With globalization, including advances in real-time information sharing via social media, information on such events is not anymore restricted to official sources. At the same time, unregulated information and inconsistent messages on an outbreak could also negatively impact response actions. A document published in March 2006 by WHO notes ‘the realtime exchange of information and advice, opening exchange between experts, community leaders or officials and the people who are at risk’ constitute risk communication [20-22]. Policy and decision-makers need to develop national capacities for risk communication as integral component of Rapid Response Teams (RRT). The communication officers would engage directly, and through social media, with communities to increase the public health awareness, promote trust building during health emergencies.

Acknowledgement

Federal and State Minister of Health, and all participants in the study and the investigation team who assisted collection of data, and the World health Organization (WHO) Country Office, Sudan for supporting the study.

References

- Perrett K, AlWali W, Read C, Redgrave P, Trend U (2000) Outbreak of meningococcal disease in Rotherham illustrates the value of coordination, communication, and collaboration in management. Commun Dis Public Health3(3): 168-171.

- Abubakar A, Bwire G, Azman AS, Malika Bouhenia, Lul L Deng, et al. (2018) Cholera Epidemic in South Sudan and Uganda and Need for International Collaboration in Cholera Control. Emerg Infect Dis 24(5): 883-887.

- Joynt GM, Loo S, Taylor BL,Margalit G, Christian MD, et al. (2010) Coordination and collaboration with interface units. Recommendations and standard operating procedures for intensive care unit and hospital preparations for an influenza epidemic or mass disaster. Intensive Care Med36(1): 21-31.

- OMalley P, Rainford J, Thompson A (2009) Transparency during public health emergencies: from rhetoric to reality. Bull World Health Organ87(8): 614-618.

- Kim K, Andrew SA, Jung K (2017) Public Health Network Structure and Collaboration Effectiveness during the 2015 MERS Outbreak in South Korea: An Institutional Collective Action Framework. Int J Environ Res Public Health14(9): 1064.

- World Health Organization (WHO) (2007) Outbreak news. Rift Valley fever, Sudan. Wkly Epidemiol Rec82(46): 401-402.

- World Health Organization (WHO) (2007)Outbreak news. Rift Valley fever, Sudan--update. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 82(48): 417-418.

- World Health Organization (WHO) (2012) Outbreak news. Yellow fever, Sudan. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 87(46): 449-460.

- World Health Organization (WHO) (2012) Yellow fever, Sudan - update. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 87(48): 477-492.

- World Health Organization (WHO) (2005) Outbreak of Ebola haemorrhagic fever in Yambio, south Sudan, April - June 2004. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 80(43): 370-375.

- World Health Organization (WHO) (1978) Ebola haemorrhagic fever in Sudan, 1976. Report of a WHO/International Study Team. Bull World Health Organ 56(2): 247-270.

- Baron RC, McCormick JB, Zubeir OA (1983) Ebola virus disease in southern Sudan: Hospital dissemination and intrafamilial spread. Bull World Health Organ 61(6): 997-1003.

- World Health Organization (WHO) (2006) Outbreak news. Meningococcal disease, Sudan. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 81(6): 51.

- World Health Organization (WHO) (2007) Outbreak news. Meningococcal disease, Sudan. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 82(8): 61.

- World Health Organization (WHO) (2005) Progress towards poliomyelitis eradication--poliomyelitis outbreak in Sudan, 2004. Wkly Epidemiol Rec80(5): 42-46.

- World Health Organization (WHO) (2005) Poliomyelitis outbreak escalates in the Sudan. Wkly Epidemiol Rec80(1): 2-3.

- World Health Organization (WHO) (2005) International health regulations (3rdedn.);World Health Organization

- Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) Reference Module for Cluster Functions.

- Carney MT, Buchman T, Neville S, Thengampallil A, Silverman R (2014) A community partnership to respond to an outbreak: a model that can be replicated for future events. Prog Community Health Partnersh 8(4): 531-540.

- (2016) Risk communication in the context of Zika viru. World Health Organization.

- Vijaykumar S, Raamkumar AS (2018) Zika reveals India’s risk communication challenges and needs. Indian J Med Ethics p. 1-5.

- Toppenberg-Pejcic D, Noyes J, Allen T, Alexander N, Vanderford M, et al. (2018) Emergency Risk Communication: Lessons Learned from a Rapid Review of Recent Gray Literature on Ebola, Zika, and Yellow Fever. Health Commun 20: 1-19.