Why did National Leaders in India, China, and Peru Impose Coercive Family Planning Policies?

Malcolm Potts1*, Martha Campbell2 and Amelia Plant3

1Bixby Centre for Population, Health & Sustainability, University of California, Berkeley, California

2 Venture Strategies for Health and Development, Berkeley, California

3 School of Public Health, University of California, Berkeley, California

Submission: May 12, 2018; Published: May 24, 2018

*Corresponding author: Malcolm Potts, Bixby Centre for Population, Health & Sustainability, University of California, Berkeley, California.

How to cite this article: Malcolm P, Martha C, Amelia P. Why did National Leaders in India, China, and Peru Impose Coercive Family Planning Policies?. JOJ Pub Health. 2018; 3(4): 555619. DOI: 10.19080/JOJPH.2018.03.555619

Abstract

The coercive family planning in India in 1975, in Peru in 1995, and the one-child policy in China have certain features in common. They all occurred in countries with rapid population growth and they all began as genuine efforts to lift people out of abject poverty. We argue that in the case of India and China the national leaders involved in coercive family planning were making decisions within a framework that emphasized distal factors of fertility, such as education and income, as driving the demographic transition, rather than the proximal factor of unfettered access to a range of family planning methods. The latter emphasis is entirely free of any implications of coercion, whereas in some settings placing all the weight on socio-economic improvements as drivers of smaller families can create a framework for incentivizing the transition to smaller families, as occurred in India. It is imperative to lift the shadow of coercion that still stalls much needed investment in family planning.

Keywords: Coercion; Family Planning; One-Child Family; Indira Gandhi; Deng Xiaoping; Demographic Transition

Introduction

Why did Indira Gandhi, Deng Xiaoping and Alberto Fujimori, in different parts of the world and at different times in the last half of the twentieth century, impose coercive family planning policies? Why did these leaders make such costly decisions? This analysis is concerned with the context in which national leaders articulated explicit policies to mandate, or forcefully encourage individual citizens to have fewer children. We accept Hardee et al. [1] definition of coercion in family planning as consisting “of actions that compromise individual autonomy, agency or liberty in relation to contraceptive use or reproductive decision making through force, violence intimidation or manipulation” Hardee et al. [1]. We hold that both coercive family planning strategies and coercive pregnancy (when women are denied access to family planning) are equally unacceptable.

Normally, the task of trying to understand historical decision making that is less than half a century away should be straightforward, but family planning and population have been rightly described as having a “contentious history” Shiffman and Quissell [2]. They have generated religious condemnation and stimulated opposing economic explanations of fertility decline, and of the impact of that decline on alleviating poverty. Many decision makers prefer to avoid these subjects all together, as happened when family planning was omitted from the 2001 Millennium Development Goals Shiffman and Quissell [2]. In such a situation we recognize that historical objectivity can be difficult. At the same time, the history of coercion in family planning continues to define public perspectives and national and international polices and deserves exploration.

We suggest that all three leaders believed that they had inherited a threatening demographic situation, brought about by prior administrative incompetence or by frank hostility to family planning by religious groups. The next step, to interpret the thinking of these leaders, is open to genuine debate. The ideology and power relations of the ruling elite are important: the caste system in India, demeaning of indigenous populations in Peru, and an obsession with planning in China have helped frame decisions about coercive family planning. The record seems to show that the three leaders began with a genuine desire to lift their citizens out of poverty and to have thought deeply about how to do achieve this goal. We will use public statements made at the time, together with observations about the intellectual frameworks in which these decisions were made, to learn from the history of coercive family planning.

The Demographic Setting

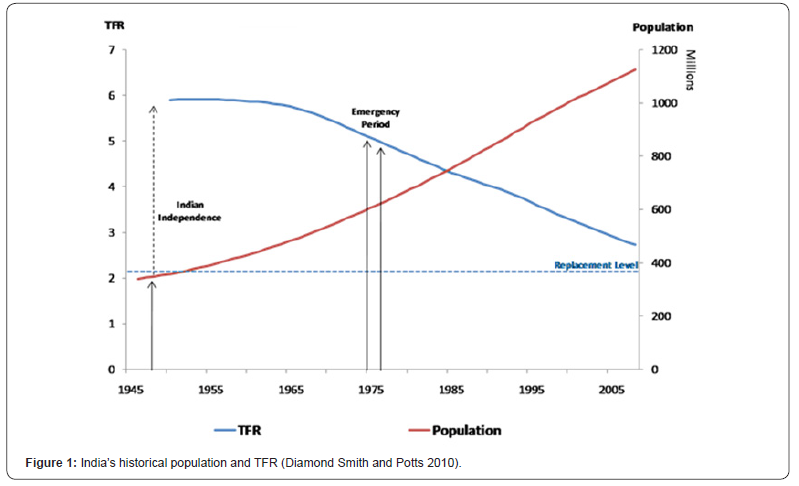

Death rates in many developing countries began to fall rapidly after World War II. This led to rapid population and early efforts to slow that growth were unsuccessful. Gandhi, Deng- Xiaoping and Fujimori came to power in nations where prior efforts to offer large-scale family planning had failed, stalled, or been actively opposed. In the 1960s the Vatican blocked a seemingly benign resolution proposing the WHO Director General to “collect information from member states as to the extent to which planned parenthood is regarded and applied as a part of preventive medicine health programmes” Suitters [3]. The 1969 Encyclical Humanae vitae opposed all forms of so-called artificial contraception. Between the Partition of India in 1947 and Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s assumption of “Emergency powers” in 1975, the population almost doubled from under 360 million to about 620 million United Nations [4,5]; United States Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census [6]. In 1975 the population was growing at 2.3% per year. The Khanna study, funded by the Population Council as early effort to promote family planning to slow population growth, mainly depended on foaming tablets, diaphragms and spermicidal jellies, and it showed no measurable impact on the birth rate Wyon and Gordon [7].

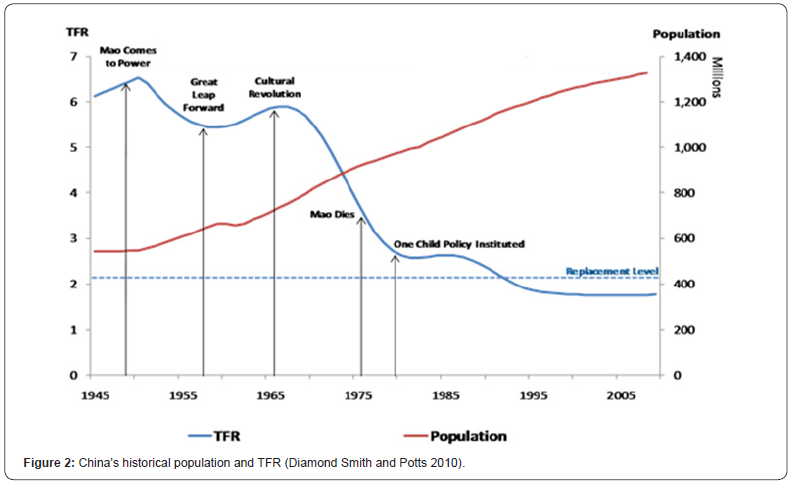

When the Chinese one-child policy was put in place in 1979, the country had seen the population grow from 545 million in 1950 to 969 million. The birth rate had fallen relatively rapidly, but there was still a great deal of demographic momentum. In 1956 the government had begun training family planning clinic workers and launched a massive promotional campaign P Chen [8], Chou[9], Mao[10]. However, these early efforts fell apart during the 1958 ‘Great Leap Forward’ and they were further disrupted by Mao’s ‘Great Proletarian Revolution’ (1966-68). Among other things, Mao closed the universities, impeding any understanding of contraceptive use or desired family size on which to build evidence-based polices. In 1970 the government introduced the slogan ‘wan xi shao’ or ‘later, longer, fewer,’ encouraging women to marry later, wait longer between pregnancies, and to have fewer children P Chen and Miller [11]. Deng Xiaoping succeeded Mao in 1976. He stressed that Chinese modernization would be impossible unless the peasants had fewer children. The Constitution (Article 53) was revised to read, “The state advocates and encourages birth-planning” P Chen and Miller [11]. Deng posited that family planning was the solution to the population problem Deng [12].

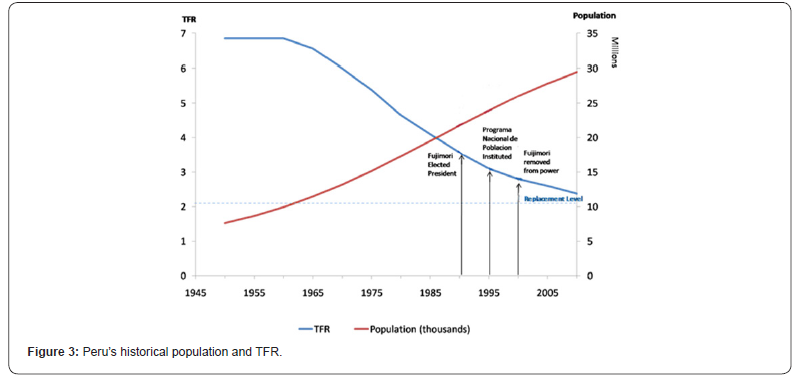

In Peru, Albeto Fujimori, trained as an agricultural engineer, mathematician and physicist, was rector of Universidad Nacional Agraria in Lima, before becoming the surprise winner of the 1990 Peruvian presidential election. He was faced with national bankruptcy, hyperinflation and a decade old Maoist guerrilla movement called the Shining Path. The population of Peru had grown from 7.6 million in 1950 to 21.7 million in 1990. Over the same interval, the TFR had decreased from 6.9 to 3.7 but, as a result of falling infant mortality, the annual percentage increase in the population had fallen less dramatically (2.5% per annum in 1950 to 1.85% in 1990) United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division [13]. The Catholic Church consistently and effectively opposed any investment in family planning, denying women access to the information and technologies they needed to limit family size. Gandhi, Deng and Fujimori were all in positions where a reasonable and concerned leader could argue that rapid population growth would have a serious adverse effect on the future of the nation. When Gandhi was prime minister, the U.S. was shipping millions of tons of grain to India to avert widespread starvation. When Deng Xiaoping came to power, 35.5% of the population was under age 15. In Peru, if there were no further change in the birth rate, the population would have doubled in less than 40 years. The three leaders were confronted by genuine demographic problems, but that does not explain why they adopted such tragically inappropriate policies.

Is Development the Best Contraceptive?

At the 1974 International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) in Bucharest, John D. Rockefeller III delivered an unexpected keynote address, partly crafted by his assistant, Joan Dunlop. His call for a “wide ranging and comprehensive” reappraisal of international family planning took off from recognition that “the [family planning] programs that have been undertaken have proved inadequate when compared with the magnitude of the problems facing us” Rockefeller [14], Harkavy [15]. In some ways Rockefeller was ahead of his time, particularly in his belief “that women increasingly must have greater freedom of choice in determining their roles in society.” His suggestion that developed nations “stabilize their own population and moderate their levels of consumption in a sensible and orderly way” still resonates half a century later, even if it remains unfulfilled.

Although it was a thoughtful speech, Rockefeller’s presentation had a polarizing effect. The Chinese delegate denied that there was a “population explosion,” asking (Shu-tse 1974:7), Is it owing to overpopulation that unemployment and poverty exist in many counties of the world today? No, absolutely not. It is the mainly due to aggression, plunder and exploration by the imperialists, particularly the superpowers.

Karan Singh, the Indian Minister of Health and Family Planning joined the disdain of stand-alone family planning programs. He encapsulated the debate Rockefeller had begun with a sound bite that continues to be heard: “Development is the best contraceptive” Potts [16].

Academics had been arguing over what drives the demographic transition from large to small families for half a century. Warren Thompson [17] and Frank Notestein [18,19] described the demographic transition that had taken place in Western Europe and North America, beginning with high birth rates and death rates and ending with low birth rates and death rates. These starting and end points of the transition had “some sort of stability,” Jones et al. [20]. Demographers also thought that, “once fertility declines are underway they tend to continue” Bongaarts [21]. Kingsley Davis [22] was an early proponent of the assumption that family size falls as social and economic conditions such as women’s education or family income, improve. The converse, that birth rates would not fall in the absence of these exogenous changes, was implied even when it was not stated explicitly – ‘development is the best contraceptive’ received strong academic backing.

Sometimes, descriptions of the demographic transition are called a ‘theory’ or a ‘model’ implying some predictive value. Paradigms change slowly and it became more common to adjust explanations of the demographic transition than to discard it Szreter [23]. When scholarly analyses “demonstrated that that there is no tight link between development indicators and fertility” Bongaarts and Watkins [24], authors still went on to assert, “The role of socioeconomic development in accounting for fertility declines remains inherently plausible.” Dudley Kirk [25] called the demographic transition theory “one of the best generalizations in the social sciences.” Classic demographic transition ‘theory’ has been taught to generations of demography and economics students. Despite the more nuanced portrayal of the demographic transition that was slowly emerging in specialized publications, most economists and policy makers retained the overarching conviction that development was the best contraceptive. This seems to have been the case with Indira Gandhi (an Oxford graduate), probably also Fujimori (a mathematician), and perhaps, indirectly, Deng Xiaoping.

Coercion Imposed

India: Prior to the 1970s, Indian and American advisers had set up an over-medical zed delivery system. Family planning was something done to people for the benefit of the country, rather than something benefiting individuals. Progress was limited. In June 1975, Gandhi declared an ‘Emergency’ and began ruling by decree. Indira and her influential son Sanjay set about ridding India of several factors that contributed to poverty and misery among India’s poor: a moratorium on repaying debts to rural money lenders; dowries (one reason girls are so disadvantaged in rural areas) were abolished Dalal et al. [26] adult literacy programs initiated; and 1.7 million acres of land were redistributed to the poor Connelly [27]. These could have led to a humanitarian triumph. So why did family planning policies annihilate these noble goals?

Fortunately, we have an explicit and unambiguous affirmation of government thinking. In the April 1976 Karan Singh wrote A National Population Policy: A Statement of the Government of India, obviously approved by the prime minister. “Removing poverty” was “a top priority”. The problem was how. Singh did not waver from “Development is the best contraceptive” put forth two years earlier. However, be began to recognize that this generated a conundrum: if socio-economic progress was essential to drive down family size, and if rapid population was making it impossible to achieve the needed development, then a leader had to either watch conditions deteriorate or devise incentives to adopt family planning. Singh (1976:310) wrote,

It is clear that simply to wait for education and economic development to bring about a drop in fertility is not a practical solution. The very increase in population makes economic development slow and more difficult of achievement. The time factor is so pressing and the population so formidable, that we have to get out of the vicious circle through a direct assault upon this problem. The National Population Policy put a nation-wide package of proposals in place. The age of marriage for girls was to be raised to 18, girls’ secondary education expanded and health facilities, including those for abortion, were to be improved. Finally (1976:311). In view of the desirability of limiting the family size to two or three it has been decided that monetary compensation for sterilization (both male and female) will be raised to Rs.150/- [$17] if performed with two living children or less, Rs.100/ [$11]-if per-formed with three living children and Rs.70/- [$8] if performed with four or more children. The plan was perceived as voluntary and it noted, “This package of measures will succeed in its objective only if it receives the full and active co-operation of its people at large” Singh [28]. At the same time, the federal government added (1976:312), we are of the view that where a State legislature, in the exercise of its own powers, decides that the time is ripe and it is necessary to pass legislation for compulsory sterilization, it may do so.

Maharashtra passed such a compulsory sterilization law, although it was never implemented. What did happen, however, was that in a poor country, with corruption at many levels and authoritarian control at the top, ‘incentives’ became increasingly coercive and ugly. Eight million people were sterilized in 1976, compared with four million before the ‘Emergency.’ Some of these operations met an existing unmet need Soonawala [29], but very large numbers of men and women were sterilized against their will. Muslims and lower caste Hindus were targeted. Despite the incentives to increase “voluntary” sterilizations, figure 1 demonstrates that the coercive programs had no significant effect on the demographic trajectory of the country (Figure 1).

Prior to 1975, the IPPF and some other western agencies had been frustrated by the failure of the Indian government to invest in family planning which may explain why they were slower than they should have been to recognize the unacceptable excesses that were arising. Even today, India finds it difficult to balance the need for numerous female tubal ligations Brault et al. [30] with safety Population Foundation of India [31] and appropriate counselling and consent.

China: In some ways the intellectual situation in China was the mirror image of that in India. It was cut off from Western based technical advice on both methods of fertility regulation and their delivery. Nevertheless, China adopted an innovative approach to new methods developing ‘no-scalpel vasectomy’, ‘paper pills’, ‘visiting pills’, and ‘vacuum aspiration abortion’, as now used all over the world, was invented in Shanghai Wu and Wu [32]. Despite their intellectual isolation, an exclusive emphasis on socio-economic improvement as the driver of fertility decline also crept into this ideologically driven society. In 1958, Mao himself declared, “When [people’s] level of education increases, [they] will practice birth control” White [33]. It is also necessary to remember that during this era of Chinese society, everything, including childbearing, was targeted and overseen by the commune. The Communist Party planned rice or steel output and it fell easily into strategies to plan births. Mao himself left no room for private decision-making, telling the Supreme State Council in 1957 [34], [We] need planned births. I think humanity is most inept at managing itself. It has plans for industrial production. [But] it does not have plans for the production of humans…If [we] go this way, I think humanity will prematurely fall into strife and hasten toward destruction.

After Mao’s death in 1976, Deng Xiaoping led the economic reform that drove China’s astonishing economic growth. In 1978 he revived the scientific tradition Mao had tried to strangle. The Chinese leaders became increasingly aware of population momentum. At the Fifth National Peoples’ Congress, Chairman Hua Guo-feng called for a “crash program over the coming 20 to 30 years calling on each couple ... to have a single child, so that the rate of population growth can be brought under control” P Chen [8]. Deng Xiaoping believed that the one-child policy must be accomplished, “otherwise, we will not be able to develop our economy, and raise the living standards of our people” Huajiao Ribo [35]. The Constitution (Article 53) was revised to read, “The state advocates and encourages birth-planning” P Chen and Miller [11]. The TFR fell from 5.5 in 1953 to 2.3 in 1978, driven primarily by widespread access to IUDs, sterilization and safe abortion. As (Figure 2) demonstrates, the one-child policy was implemented when the country was over eight tenths of the way to replacement level fertility. The pace at which it might have completed the demographic transition without the one-child policy will never be known (Figure 2).

The key one-child policies were made by scientists trying to recover from the years when Mao had labeled scientists “feudal” and “bourgeois,” and banished them to raise pigs in village communes. The only group with access to a modern computer and the freedom to travel to Europe was a team of missile engineers led by Song Jian. Susan Greenhalgh [36] posits that, “all the key ideas on which China’s one-child policy were borrowed from the West, and from Western science at that.” We do know that Chinese Premier Chou En-lai quizzed Pakistani diplomats in Beijing about the Pakistani family planning effort. Song and his colleagues demonstrated, largely correctly, that relatively small changes in family size of the order of an average of half a child would alter the population of China by a billion later in the century. Greenhalgh emphasized that Song Jian was greatly influenced by the 1972 Club of Rome Report, The Limits to Growth Meadows et al. [37]. The Limits to Growth, citing the work of Spengler [38] placed an explicit and unambiguous emphasis that development is the best contraceptive: The relation between crude birth rate and GNP per capita of all nations in the world follows a surprisingly regular pattern. In general, as GNP rises, the birth rate falls. This appears to be true despite difference in religious, cultural or political factors.

In a less revolutionary environment and with more data, China might have developed a less extreme policy, but in the historical context of the time and the uncontested belief that “as GNP rises, the birth rate falls,” then the one-child family can be seen as a sincere, if mistaken belief, that such a policy was essential in order to lift people out of poverty. It was certainly the most radical social policy development of any country in the twentieth century. As in India, China’s coercive policies were politically costly, although the Communist Party set a nationwide example by imposing the one-child policy with special vigor on party members. The implementation of the policy varied between provinces. Usually, couples accepted the benefits of a one-child certificate, which made better food rations available and opened the door to improved education for their child. However, they balked at repaying these benefits when a second child was conceived, and often found them driven to have an abortion. Interestingly, the one-child policy did not apply to the tens of millions of non-Han Chinese minorities. It is uncertain whether this was a respect for minorities, or a realization that the policy could not be enforced. One reason the one-child family remained in force until 2015 was that local bureaucrats are thought to have been taking $2 billion a year in take bribes to look the other way when a couple had a second child Pei [39].

Peru: Born of Japanese parents, President Alberto Fujimori was brought up Roman Catholic. In 1985 a National Law on Population made family planning available, but a combination of Catholic hostility and medical conservatism, which focused on clinics rather than empowering communities to help themselves, meant that family planning choices did not reach the rural poor. The Church resisted making voluntary sterilization or safe abortion available Boesten [40], a policy that negatively impacted the rural indigenous peoples of Peru, eight out of 10 of whom lived in extreme poverty and three quarters of whom were illiterate Alvarado and Echegaray [41]. Like Gandhi in India, initially Fujimori showed every sign of genuinely wanting to help the poor. Fujimori was the only head of state to attend the 1995 Beijing Women’s Conference. He outlined his government’s family planning initiative; my government has decided to carry out, as part of a policy of social development and the fight against poverty, an integral strategy of family planning that confronts, openly - for the first time in the history of our country - the serious lack of information and services available on this matter. Thus, women can have at their disposal with full autonomy and freedom, the tools necessary to make decisions about their own lives.

He was explicit-and many thought justified-in the need to confront the long history of Catholic opposition to family planning, saying, The Church is trying to prevent the Peruvian State from carrying out a modern and rational policy of family planning. We have been accused of trying to impose “mutilations” and “killing poor people” after a recent law was passed by Congress allowing voluntary vasectomies and fallopian tube ligation as part of contraceptive methods. Fujimori was impatient with an elected, but in the eyes of many, an incompetent congress. While Gandhi had ruled by Emergency Decree, Fujimori and the military engineered an autogolpe or ‘auto-coup’ in 1992. Gaining absolute power, he introduced legal reforms to help the poor. His economic policies included privatizing state enterprises enabling Peru to become one of the most successful economies in Latin America.

A free election was held in 1995 and Fujimori won a landslide victory. Instead of building on this support he became increasingly tyrannical and corrupt. He declared, “The government cannot reduce poverty efficiently if poor families continue to have on average seven children” Aramburu [42]. Genuine improvements in family planning were put in place, attracting initial support from women’s rights groups in the country Alvarado and Echegaray [41] and external donors, including USAID. For a while the family planning budget exceeded that of other health programs [41]. Voluntary sterilization was legalized. The 1995 Programa Nacional de Poblacion guaranteed reproductive rights. Legislation “Outlawing Violence against Women” was passed. Efforts were set in motion to improve education, although the Catholic Church continued to forbid sex education.

While Fujimori framed family planning in human rights terms, he failed to prevent the military from launching a coercive family planning strategy aimed at the indigenous population. The Shining Path (Sendero Luminoso) was a Maoist organization that began adopting increasingly violent tactics in the 1980s, strangling and stoning those who opposed it U.S. Department of State [43]. The 1989 plan the military put together for a Government National Reconstruction (Plan Verde) mandated sterilization of “surplus beings [through a] generalized sterilization use among those culturally backward and impoverished groups” (Getgen 2009). Incentives to family planning workers increased substantially. Between 1996 and 2000, surgeons carried out 215,227 sterilizations on women and 16,570 male vasectomies. At least 500 men and women from Cuzco and Ancash told a special commission they had been forcibly sterilized Gamini [44]. As a cable from the U.S. Embassy in Lima said in 1993, “while Fujimori understands the importance of human rights, in practice he is prepared to sacrifice principles to achieve a quick victory over terrorism” U.S. Embassy Cable [45]. As reflected in Figure 3 the episode of coercive sterilizations made no impact on fertility decline (Figure 3).

In 2009 Fujimori was sentenced to 25 years in prison on charges of corruption and a range of human rights atrocities, including kidnapping and assassination. On January 8, 2015, he was sentenced to eight additional years in prison on new counts of using state funds to bribe the media in the lead-up to his re election campaign in 2000 Kozak [36]. The political fallout for Gandhi and Fujimori was catastrophic. Gandhi lost the next election and Fujimori remains in prison. For the Chinese leadership internally the one-child policy, as Deng had put it, presented “a difficult task” Huajiao Ribo [35] and it has been extremely harmful for the image of the country in the eyes of the rest of the world.

Is Contraception the Best Development?

Karan Singh’s 1976 National Population Policy demonstrates that the ‘development is the best contraceptive’ paradigm was an important factor pushing Indian decision makers towards the slippery slope of coercion [46]. The evidence is less compelling, but it also seems that the Chinese established the one-child policy because they had adopted the same model of the demographic transition. One of the authors (MP) sat beside Karan Singh at the closing session of the 1992 IPPF Family Planning Conference in New Delhi [47]. In the discussion section following the presentation, Singh rather plaintively said Potts [16], in 1974, I led the Indian delegation to the World Population Conference in Bucharest, where my statement that development’. is the best contraceptive’ became widely known and oft quoted. I must admit that 20 years later I am inclined to reverse this and my position now is that ‘contraception is the best development’. Divisions between proponents of development as the best contraceptive and contraception as the best development goes back to the 1960s. The distinguished demographer, Kingsley Davis (1966) called the family planning programs being launched by USAID “either quackery or wishful thinking.” Reimert Ravenholt, who led these programs, replied Ravenholt [48]. It seems reasonable to believe that when millions of women throughout the world need only reproduce when they choose, then the many intense family and social problems generated by unplanned, unwanted and poorly cared for children will be greatly ameliorated and the now acute problems of too rapid population will be reduced to manageable proportions.

One of the authors (MP) wrote in the Tenth Darwin Lecture in 1970 (Potts 1970), some writers are asking ‘What is beyond family planning?’ They are talking about incentives where previously they spoke of motivation. Reports of transistor radios are becoming tales of compulsory sterilization or hormones in the drinking water. I think this trend is dangerous and unnecessary. The ideal of voluntary parenthood is an exceptionally important freedom to preserve. I fear it is threatened with erosion because we are failing to make a free choice of contraceptive methods available… Connelly (2008), who framed every aspect of international family planning prior to 1994 as a plot by eugenicists akin to Nazis, criticized Ravenholt but actually ends up writing an eloquent exogenesis on non-coercive family planning policies, Ravenholt’s office was virtually alone in its policy of refusing support for programs to create demand for contraception. He argued that supplying ‘unmet need’ would be enough to solve the problem of population growth, or was at least worth trying before trying anything else. Many of his superiors and subordinates disagreed, and pressed Ravenholt for experiments with incentives.

Over the past half century the thesis that if women are given unfettered access to the knowledge and the technology needed to manage their fertility then average family size will fall - even in a poor and illiterate society - has gained a academic and empirical support [21,49-57]. Those emphasizing proximal determinants of fertility highlight the many tangible and intangible barriers preventing women from accessing the family planning technologies and information needed to separate frequent sex from childbearing Campbell et al. [58]. Wealthy women can usually obtain a safe abortion even where abortion is notionally illegal, while poor women cannot. Access to safe abortion can lower the TFR substantially even when the contraceptive prevalence rate (CPR) is held constant Campbell and Bedford [10].

On the ‘development is the best contraceptive’ side of the debate, Prichett [59] asserts that couples will always find ways to limit family size through free market forces because the costs of fertility regulation are always lower than those of an unintended pregnancy. More recently, in the 2008 The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists Joseph Chamie (former Director of the UN Population Division) emphasized the need for socioeconomic change, reducing national population growth rates involves more than simply reducing unintended fertility” Chamie [60]. In doing so he found himself in exactly the trap Kingsley Davis had faced in the 1960s and Indira Gandhi in the 1970s. If development is the best contraceptive, then in Chamie’s [61] words, for some nations, voluntary behavioural changes may be sufficient to alter demographic trends and unsustainable, environmentally damaging practices. However, as Kingsley Davis and then Garrett Hardin forcefully argued in Science in 1967 and 1968, respectively, voluntary programs to modify individual behaviour tend to fall short of intended goals. In such cases, legislation, programs, and incentives that encourage responsible parenting and sustainable resource use must be mandated in order to achieve population stabilization and reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Predictably, Chamie’s arguments produced a vigorous and critical response from Betsy Hartmann of Hampshire College in Amherst, Massachusetts, although she continued to assert development is the best contraceptive Chamie [60] with increasing education, urbanization, and women’s work outside the home, birth-rates have fallen in almost every part of the world and will likely continue to do so, particularly as urbanization accelerates. Chamie is a humane person and Hartmann is one of the most eloquent opponents of coercion. Both believe that socioeconomic improvement is the prerequisite for slowing rapid population growth. Chamie advocates mandating “legislation, programs, and incentives that encourage responsible parenting.” Hartman simply avoids the issue.

The Paradox of the 1994 ICPD

The ICPD, held in Cairo in 1994, occurred at a time when there seemed to be grounds for optimism: the success of the focused family planning programs of the 1970s and 80s had created a false assurance that birth-rates would continue to fall; the growth in the food supply had largely kept pace with the growth in population; the global economy was expanding; and the Cold War had just ended. The sombre forecasts of a world running out of finite resources made in The Limits to Growth in 1972 Meadows et al. [34] seemed unduly pessimistic. Nearly all the preparatory meetings leading up to the ICPD were strongly influenced by women’s groups, who sought to shift attention from population growth to the many other needs of poor women around the world, including more comprehensive reproductive health care, economic opportunity, property ownership and a reduction in violence Campbell [62]. At their most extreme, some women’s groups created what has been called “a myth” Sinding [63] that everything before Cairo had been a coercive, target-driven effort to control population. While it was assumed the reproductive health would include family planning, the terms “population” and “family planning” were framed as politically incorrect Campbell and Bedford [10]. Joan Dunlop (who had helped frame Rockerfeller’s 1974 Burcharest speech) described the tactics of women’s groups in the following words Goldberg [64], What we wanted to do was, rather, simply [not] throwing the baby out with the bathwater; we wanted to redirect the money. We knew there were huge streams of money going into contraceptive development, and we wanted that money to go in a different direction. The assertion “of huge streams of money going into contraceptive development” was false. Contraceptive development was a small part of foreign aid family planning budgets. In turn, family planning budgets rarely amounted to more than one percent of the all the money flowing from developed to developing countries. Lacking a sense of scale, and trying to “redirect’ the family planning money undermined family planning budgets. After 1994 there was a precipitous switch from action to improve family planning to a broader, more holistic approach, aimed at improving the health and social status of women. However, these goals failed to gain political traction among donors, and budgets collapsed Spiedel [65]. The fertility decline, which had begun over the preceding decades stalled. Many token projects were started with the aim of implementing the broader goal of improving sexual and reproductive health that Dunlop and others wanted. Many were not brought to scale, and some were just not scalable. Dirk van de Kaa (1996) of the Netherlands commented, the [ICPD conference was ready to deal with everything as long as it did not relate directly to the mundane issue of population growth and the need to generate the financial resources necessary to enable people everywhere to plan their families responsibly. The ideal began to undermine the achievable. As a recent World Bank report (2010) pointed out, the comprehensive approach to reproductive health, adopted at the 1994 Cairo Conference, was doubtless too large for many countries in sub-Saharan Africa the adoption of a comprehensive approach to reproductive health pushed family planning to the side.

Conclusions

Taking the emphasis off family planning in 1994 allowed a great deal of demographic momentum to build, especially in sub- Saharan Africa [66]. The annual increase in global population (2015: 87.4 million more births than deaths) is the highest in human history Population Reference Bureau [67]. Over 98% of this growth is in less developed regions of the world. Focusing on family planning and safe abortion is essential in this era of rapid population growth and increasingly scant resources, but the shadow of coercive family planning continues to make many contemporary policy makers reluctant to focus attention on the need for voluntary family planning. The architects of coercive family planning all began with the goal of lifting the poor out of poverty. All three had the potential for greatness. Had Indira Gandhi’s efforts to improve the status of women, help poor farmers and redistribute land not been undermined by coercive family planning, they would have been hailed as a triumph of humane government. Fujimori had taken Peru from bankruptcy to the most rapidly growing economy in the world and in the process he had defeated a major terrorist movement. Deng, by opening up the free market, was perhaps the chief architect of China’s remarkable economic growth, and for this reason one of the most important decision makers of the twentieth century. His economic policies helped lift 300 million people out of abject poverty. The question in the minds of many is whether the onechild policy was needed to achieve this.

So What Went Wrong?

Was coercive family planning in Peru a strange, inexplicable episode in the history of family planning, or yet another example of the terrible human ability to dehumanize ‘an outgroup’? Potts and Hayden [68]. The Shining Path had massacred peasants, including children Amnesty International [69], whiles the military razed villages and killed campesinos. Nixon/ Kissinger during the Vietnam War Shaw cross [70], and Bush/ Cheney with the Guantanamo detention centre and the invasion of Iraq, also lost their moral compasses fighting terrorists. We suggest that the coercion under Fujimori was driven primarily by the racist ideology of the military elite. In the case of Gandhi and Deng we suggest that they placed excessive weight on the standard conceptual scheme that socio-economic factors drive fertility decline. Poignantly, the most vocal proponents of human rights at the 1994 ICPD remain wedded to the standard socioeconomic model. Hodgson and Watkins (1997) saw the ICPD having adopted the paradigm, that fertility decline was a consequence of the developmental process and not a catalyst, as the only way to insure its occurrence was by the indirect route of promoting development. Such a vision of fertility decline as a necessary consequence, not a cause, of large societal changes was to provide the frame that feminists would modify for later use at the 1994 Cairo conference.

At its most radical, this vision of reproductive rights even suggests that anyone (the authors called them neo-Malthusians) “asserting the efficacy of birth control activities at the societal” level or “lobbying for special funds for family planning” as “an infringement of reproductive rights” (Hodgson and Watkins 1997). This is an extreme philosophy with unfortunate implications for women. First, in saying that “fertility decline was a consequence of the developmental process”, the authors are adopting the framework that helped lead to coercive family planning policies in India and China. Second, it is this ideology which contributed heavily to the diversion of most of the family planning funds which has left millions of poor and vulnerable women worse off than they were before Cairo. In sub-Saharan Africa the number of women living in absolute poverty has grown and the disparities in TFR between the upper and lower economic quintiles has risen (All Party Parliamentary Group on Population [71,72], with somber implications for the education and health of the poorest economic quintiles. These disappointing results, in significant measure, are driven by continuing rapid population growth.

We need to ask, could coercion happen again, and if so, what policies might make such a catastrophe least likely to occur? The growing disparity in TFR between the rich and poor within countries inevitably translates into sad inequities in education, employment and the life-long pursuit of happiness. If strong, impatient leaders, or powerful international agencies, really believe that socioeconomic development is a prerequisite for fertility decline, then we may see future episodes of coercion in family planning. In May 2015, the President of Myanmar signed the Population Control Health Care Bill into law, despite international outcries of an anti-Muslim agenda. The bill requires women to space pregnancies 36 months apart Perria [73]. Unfortunately the era of coercive family planning policies is not behind us [74-78].

On the other hand, if leaders strengthen access to family planning and abortion, such as in the case of Ethiopia, fertility decline will accelerate. Hodgson and Watkins (1997:489) pointed out that “fertility decline is a necessary consequence of the empowerment of women.” Giving women the power to decide if and when to have a child is the first, essential step towards that empowerment. Condemning efforts to prioritize voluntary family planning policies and funding as, “infringement[s] of reproductive rights” is illogical [79-84].

Gender equity, the elimination of violence against women and facilitating the economic empowerment of women are all unfettered goods. Poor and vulnerable women will benefit most if policy makers, women’s health advocates, and those seeking to slow rapid population growth all accept that a major goal for the “empowerment of women” has to be an unambiguous, explicit and enthusiastic commitment to renewed investment in family planning and to reducing the barriers to contraception Campbell et al. [73] and safe abortion in the context of accurate information and voluntary choice. It is a simple, honourable, and achievable goal offering huge benefits to individual women, their families, the society in which they live and the future of a unique, finite but fragile planet.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Virginia Gidi for help in preparing the manuscript and especially for assistance on documentation of events in Peru in the 1990s, and Nadia Diamond Smith for the three figures.

References

- Hardee K, Harris S, Rodriguez M, Kumar J, Bakamjian L, et al. (2014) Achieving the goal of the London summit on family planning by adhering to voluntary, rights-based family planning: What can we learn from past experiences with coercion? International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health 40(4): 206-214.

- Shiffman J, Quissell K (2012) Family planning: A political issue. The Lancet 380(9837): 181-185.

- Suitters B (1973) Be brave and angry: Chronicles of the international planned parenthood federation. International Planned Parenthood Federation, London UK.

- United Nations (1952) Demographic yearbook 1952 (No 4) New York: Statistical Office of the United Nations, Department of Economic Affairs.

- United Nations (1995) Unofficial translation from Spanish original speech given by president of the republic of Peru, HE Alberto Fujimori before the IV world conference on women, China.

- US Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census. (1979) Current population reports: Illustrative projects of world populations to the 21st century. Washington, DC: United States Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, USA 79: 23.

- Wyon JB, Gordon JE (1971) The khanna study: Population problems in the rural punjab. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, USA.

- Chen P (1981) Rural health and birth planning in china. Research Triangle Park. North Carolina: International Fertility Research Program, USA.

- Chou E (1959) Report of the proposals of the second five-year plan for the development of the national economy. Renmin Ribao (People’s Daily).

- Mao T (1949) The bankruptcy of the idealistic historicism. Selected works of Mao Tse Tung, vol 4 (pp. 1515-1516) Beijing: Remind Publishing Company.

- Chen P, Miller AE (1975) Lessons from the Chinese experience: China’s planned birth program and its transferability. Studies in Family Planning 6(10): 354-366.

- Deng X (1979) The selected works of Deng Xiaoping, volume II: Uphold the four cardinal principles

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. (2013). World population prospects: 2012 revision. New York: United Nations, USA.

- Rockefeller JD (1978) Population growth: The role of the developed world. Population and Development Review, 4(3), 509-516.

- Harkavy O (1995) Curbing population growth: An insider’s perspective on the population movement. New York: Plenum, USA.

- Potts M (1992) Contraception is the Best Development. (Commentary) The Lancet 340:1201.

- Thompson W (1929) Population. American Journal of Sociology 34: 959-975.

- Notestein FW (1953) Economic problems of population change. Eighth international conference of agricultural economics. London: Oxford University Press, UK, p. 13-31.

- Notestein FW (1944) Problems of policy in relation to areas of heavy population pressure. The Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly 22(4): 424-444.

- Jones GW, Douglas RM, Caldwell JC, D Souza RM (1997) The continuing demographic transition. Oxford: Clarendon Press, USA.

- Bongaarts J (2003) Completing the fertility transition in the developing world: The role of educational differences and fertility preferences. Population Studies 57(3): 321-335.

- Davis K (1967) Population policy: Will current programs succeed? Grounds for skepticism concerning the demographic effectiveness of family planning are considered. Science 158(3802): 730-739.

- Szreter S (1993) The idea of demographic transition and the study of fertility change: A critical intellectual history. Population and Development Review 19(4): 659-701.

- Bongaarts J, Watkins SC (1996) Social interactions and contemporary fertility transitions. Population and Development Review 22(4): 639- 682.

- Kirk D (1996) Demographic transition theory. Population Studies 50(3): 361-387.

- Dalal K, Rahman F, Jansson B (2009) Wife abuse in rural Bangladesh. Journal of Biosocial Science 41(5): 561-573.

- Connelly M (2008) Fatal misconception: The struggle to control world population. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University, USA.

- Singh K (1976) National population policy: A statement of the government of India. Population and Development Review 2(2): 309- 312.

- Soonawala RP (1993) Family planning: The Indian experience. In P Senanayake, RL Kleinman (Eds.), Family planning: Meeting challenges: Promoting choices, Carnforth, UK: The Parthenon Publishing Group, UK, p. 77-90.

- Brault MA, Schensul SL, Singh R, Verma RK, Jadhav K (2015) Multilevel perspectives on female sterilization in low-income communities in Mumbai, India. Qualitative Health Research 26(11):1550-60.

- Population Foundation of India (2014) Robbed of choice and dignity: Indian women dead after mass sterilisation. Situational assessment of sterilisation camps in Bilaspur district, Chhattisgarh. New Delhi: Population Foundation of India, India.

- Wu Y, Wu X (1958) A report of 300 cases using vacuum aspiration for the termination of pregnancy. Chinese Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 6: 447-449.

- White T (1994) The origins of china’s birth planning policy. In CK Gilmartin, G Hershatter, L Rofel, T White (Eds.)., Engendering china: Women, culture and the state. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, USA, pp. 250-278.

- Mao T (1989) On the correct handling of contradictions among the people. In R MacFarquhar, E Wu, T Cheek (Eds.)., The secret speeches of chairman Mao: From the hundred flowers to the great leap forward, Harvard Contemporary China Series, Cambridge: Harvard University Asia Center.

- Huajiao Ribo (1980) Huajiao Ribo (Overseas Chinese Daily). New York, USA.

- Greenhalgh S (2003) Science, modernity, and the making of china’s one-child policy. Population and Development Review 29(2): 163-196.

- Meadows DH, Randers J, Meadows DL, Behrens WW (1972) The limits to growth: A report for the club of Rome’s project on the predicament of mankind. New York: Universe Books, USA.

- Spengler JJ (1966) Values and fertility analysis. Demography 3(1): 109- 130.

- Pei M (2015) China’s one-child policy may be abolished, but its damage is far from over. The Huffington Post.

- Boesten J (2007) Free choice or poverty alleviation? Population politics in Peru under Alberto Fujimori. European Review of Latin American and Caribbean Studies 82: 3-20.

- Alvarado SC, Echegaray JN (2009) Going to extremes: Population politics and reproductive rights in Peru. In LA Mazur (Eds.), A pivotal moment: Population, justice and the environmental challenge, Washington, DC: Island Press, USA.

- Aramburu CE (2002) Politics and reproductive health: A dangerous connection. Bangkok, Thailand: Interregional Seminar on Reproductive Health, Unmet Needs, and Poverty

- US Department of State (1996) Peru Human Rights Practices, 1995. Washington, US Department of State, USA.

- Gamini G (2002) Peru leader tried to sterilise the poor by force. The Times (London).

- US Embassy Cable (1993) In National Security Archive Posts Declassified Evidence Used in Trial: US Documents Implicated in Fujimori Repression, Cover-up. Washington, DC: US Department of State, USA.

- Kozak R (2015) Peru court gives Fujimori a fifth prison sentence. The Wall Street Journal.

- Senanayake P, Kleinman RL (1993) Family planning: Meeting challenges, promoting choices. London: International Planned Parenthood Federation, UK.

- Ravenholt RT (1969) AID’s family planning strategy. Science 163(3863): 124-127

- Campbell M, Bedford K (2009) The theoretical and political framing of the population factor in development. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences 364(1532): 3101-3113.

- Campbell M, Prata N, Potts M (2013) The impact of freedom on fertility decline. The Journal of Family Planning and Reproductive Health Care / Faculty of Family Planning & Reproductive Health Care, Royal College of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists 39(1): 44-50.

- Cleland J, Bernstein S, Ezeh A, Faundes A, Glasier A, et al. (2006) Family planning: The unfinished agenda. The Lancet 368(9549): 1810-1827.

- Majumder N, Ram F (2015) Explaining the role of proximate determinants on fertility decline among poor and non-poor in Asian countries. PloS One 10(2): e0115441.

- O Sullivan JN (2015) The infrastructure dividend: Conceptualising and quantifying the cost of providing capacity for additional people.

- Potts M (2014) Getting family planning and population back on track. Global Health, Science and Practice 2(2): 145-151.

- Potts M, Pebley AM, Speidel JJ (2009) Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences 364(1532): 2975-2976.

- Prata N (2009) Making family planning accessible in resource-poor settings. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences 364(1532): 3093-3099.

- Campbell M, Sahin Hodoglugil NN, Potts M (2006) Barriers to fertility regulation: A review of the literature. Studies in Family Planning 37(2): 87-98.

- Pritchett LH (1994) Desired fertility and the impact of population policies. Population and Development Review 20(1): 1-55.

- Chamie J (2008) When the world is at stake, personal rights and sovereignty aren’t perfectly clear. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, Population and Climate Change.

- Campbell M, Cleland J, Ezeh A, Prata N (2007) Public health. Return of the population growth factor. Science 315(5818): 1501-1502.

- Sinding SW (2001) Global fertility transitions (Population and Development Review ed) New York: Population Council, USA.

- Goldberg M (2009) The means of reproduction: Sex, power, and the future of the world. The Penguin Press, New York, USA.

- Potts M, Gidi V, Campbell M, Zureick S (2011) Niger: Too little, Too Late. International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health 37: 95- 101.

- Potts M, Graves A (2013) Big issues deserve bold responses: Population and climate change in the Sahel. African Journal of Reproductive Health 17(3): 9-14.

- Population Reference Bureau (2015) 2015 world population data sheet. Washington, DC. Population Reference Bureau, USA.

- Potts M, Hayden T (2009) Sex and war: How biology explains warfare and terrorism and offers a path to a safer world. BenBella Books, Dallas, USA.

- Amnesty International (1996) Peru: Prisoners of conscience. London: Amnesty International, UK.

- Shawcross W (1979) Sideshow. Simon & Schuster, New York, USA.

- All Party Parliamentary Group on Population, Development and Reproductive Health (2007). Return of the population growth factor: Its impact upon the millennium development goals. London: All Party Parliamentary Group on Population, Development and Reproductive Health, UK.

- Campbell M (2007) Why the silence on population? Population and Environment 28(4-5): 237-246.

- Perria S (2015) Burma’s birth control law exposes Buddhist fear of Muslim minority. The Guardian.

- Chen M (1979) To realize the four modernizations, it is necessary to control population in a planned way. Renmin Ribao (People’s Daily).

- Ding QJ, Hesketh T (2006) Family size, fertility preferences, and sex ratio in china in the era of the one child family policy: Results from national family planning and reproductive health survey. BMJ 333(7564): 371-373.

- Hesketh T, Lu L, Xing ZW (2005) The effect of China’s one-child family policy after 25 years. The New England Journal of Medicine 353(11): 1171-1176.

- Human Rights Watch (2003) La comisión de la verdad y reconciliación.

- Knodel J, Wongsith M (1991) Family size and children’s education in Thailand: Evidence from a national sample. Demography 28(1): 119- 131.

- Lahey JN (2014) The effect of anti-abortion legislation on nineteenth century fertility. Demography 51(3): 939-948.

- May JF (2012) World Population Policies: Their Origin, Evolution, and Impact. New York: Springer, USA.

- Meade JE (1967) Population explosion, the standard of living and social conflict. The Economic Journal 77(306): 233-255.

- Potts M (1999) Sex and the Birth Rate: Human Biology, Demographic Change, and Access to Fertility-Regulation Methods. Population and Development Review 23: 1-40.

- Potts M (1999) The population policy pendulum needs to settle near the middle and acknowledge the importance of numbers. BMJ 319(7215): 933-934.

- Rousseau S (2006) Women’s citizenship and neopopulism: Peru under the fujimori regime. Latin American Politics and Society 48(1): 117- 141.

- Sachs J (2005) The end of poverty: Economic possibilities for our time. New York: Penguin Books. US Central Intelligence Agency. The world factbook, USA.

- (2015) US Central Intelligence Agency. The world factbook.