Abstract

Wood flooring is often a key element in expressing the historic character of traditional buildings, serving both as a defining material and as an integral component of significant interior spaces. Its type, construction, finish, and visual qualities frequently reflect the original function, period, and stylistic context of a building, from utilitarian plank floors in industrial structures to highly decorative parquetry in prominent residential and public interiors. Because of this close relationship between material and meaning, the preservation of historic flooring requires careful evaluation of its significance within the broader architectural and spatial composition. Such an assessment must consider whether the flooring lies within a primary or secondary space, whether it embodies distinctive craftsmanship or construction techniques, and whether it represents characteristics typical of the building’s type, period, or use. The physical condition of the flooring is equally important, including the extent of deterioration, the remaining integrity of the space, and the feasibility of repair.

Guided by the Standards for Rehabilitation preservation practice prioritizes the retention and repair of character defining features. Replacement is recommended only when deterioration is so extensive that repair is no longer reasonable. In such cases, the degree to which the replacement must match the historic flooring depends on the significance of the space and the intactness of the surviving material. Primary spaces with high architectural integrity typically require close matching of material, dimensions, pattern, and appearance, while secondary spaces may allow for more flexibility, including the use of substitute materials. Practical factors such as hazardous material contamination, repair feasibility, and programmatic requirements including accessibility, fire separation, or acoustic performance, may also justify the use of alternative materials. When replacement is necessary, key characteristics such as board dimensions, connection details, layout patterns, and finish qualities should guide the selection to ensure continuity with the historic character of the building.

Keywords:Wood; Historic flooring; Replacement; Requirements

Introduction

Reinforcing interventions

The performance of buildings against seismic vibrations in the general sense depends both on the interconnection between the constituent elements and on the resistance, stiffness and ductility of the individual elements. When the individual elements of the structural system are reinforced, care must be taken to ensure uniform distribution of stiffness in two directions in the plan [1].

In the case of reinforcement with additional structural elements, e.g. columns or reinforced concrete walls, attention must be paid to the uniform distribution of stiffness in height, in order to prevent its immediate changes from one floor to another. Below are some recommendations that must be followed to have an efficient repair of the damaged structure:

i.

Structural walls must be uniformly distributed in two directions in the plan.

ii.

Structural walls must interact during the action of loads through the implementation of rigid interflow diaphragms.

iii.

The floors of the basement must be connected to the walls of the structure through tie rods that limit the walls from working out of their plane, during the earthquake.

iv.

The foundations are reinforced to ensure adequate transfer of loads to the foundation.

v.

The purpose of the strengthening intervention is:

vi.

Ensuring the monolithic three-dimensional behavior of

the structure after reinforcement, to the action of seismic forces,

through the appropriate connection of the walls to each other and

of the walls to the floors.

vii. Ensuring the smoothest possible path of the transmission

of seismic loads from the roofs and floors of the basement to the

stone masonry and further to the foundations.

Three-dimensional behavior is a minimum required for the application of analytical methods of seismic analysis of buildings as a whole [2]. This analysis requires the application of the mechanism of limiting the work of the walls outside the plane which is achieved by:

i. Metal ties.

ii. Circular bars that create closed and continuous contours.

iii. Suitable joints.

iv. Ring beams or belts.

Anchoring of floors and roofs to walls

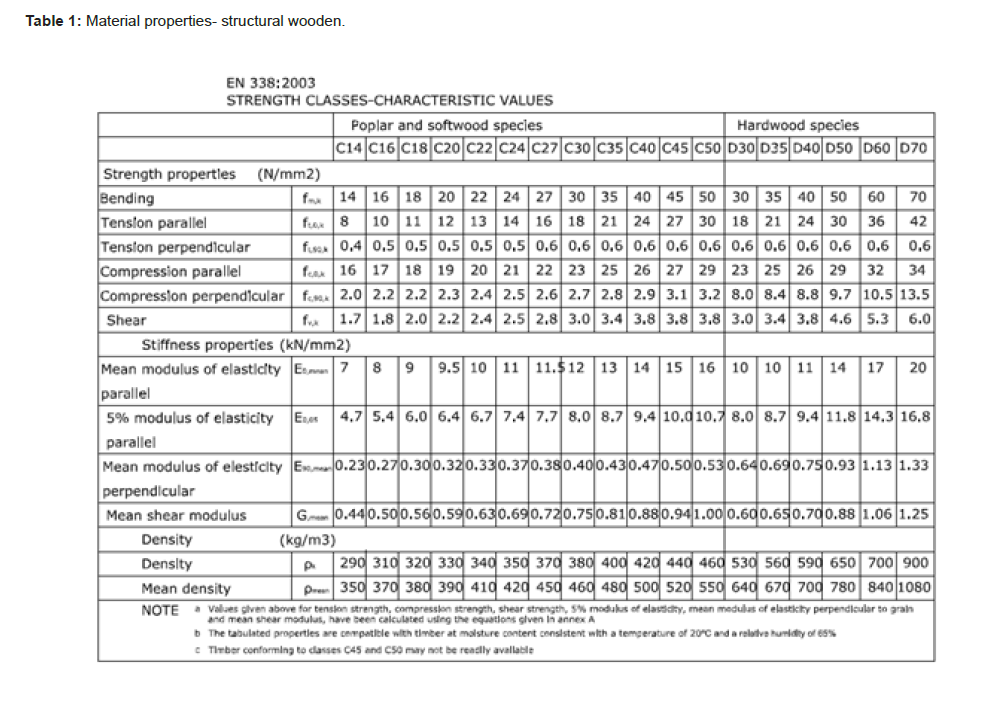

In buildings with stone masonry and wooden floors, the horizontal and vertical wall bracings are not sufficient to ensure monolithic behavior, causing significant out-of-plane bending of the walls, Figure 1, especially in cases where the distance between the transverse walls is considerable (L≥7.0m).

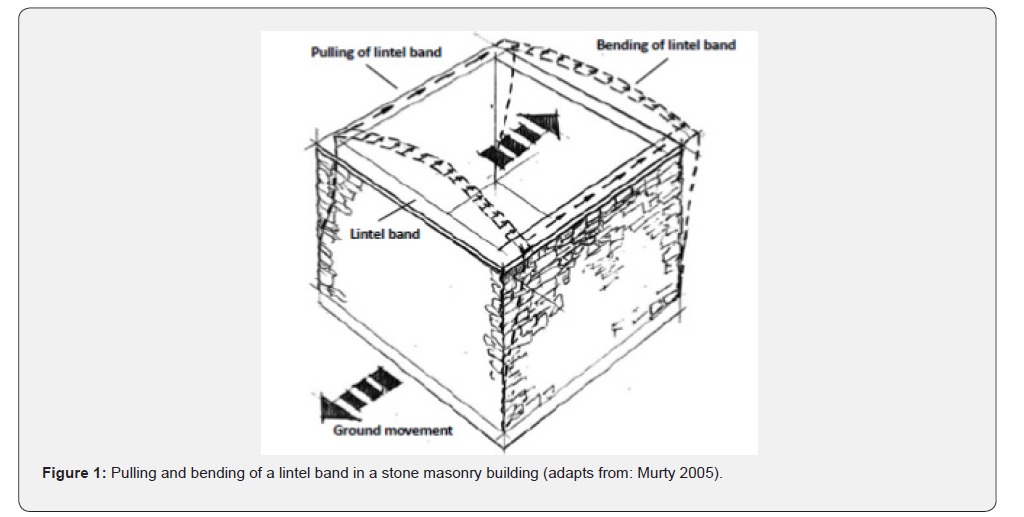

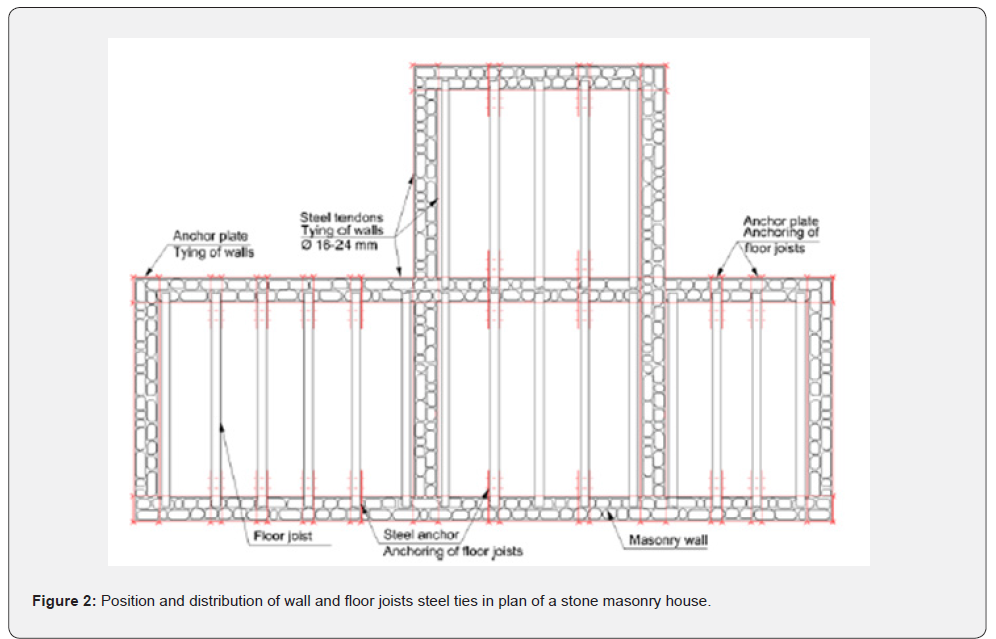

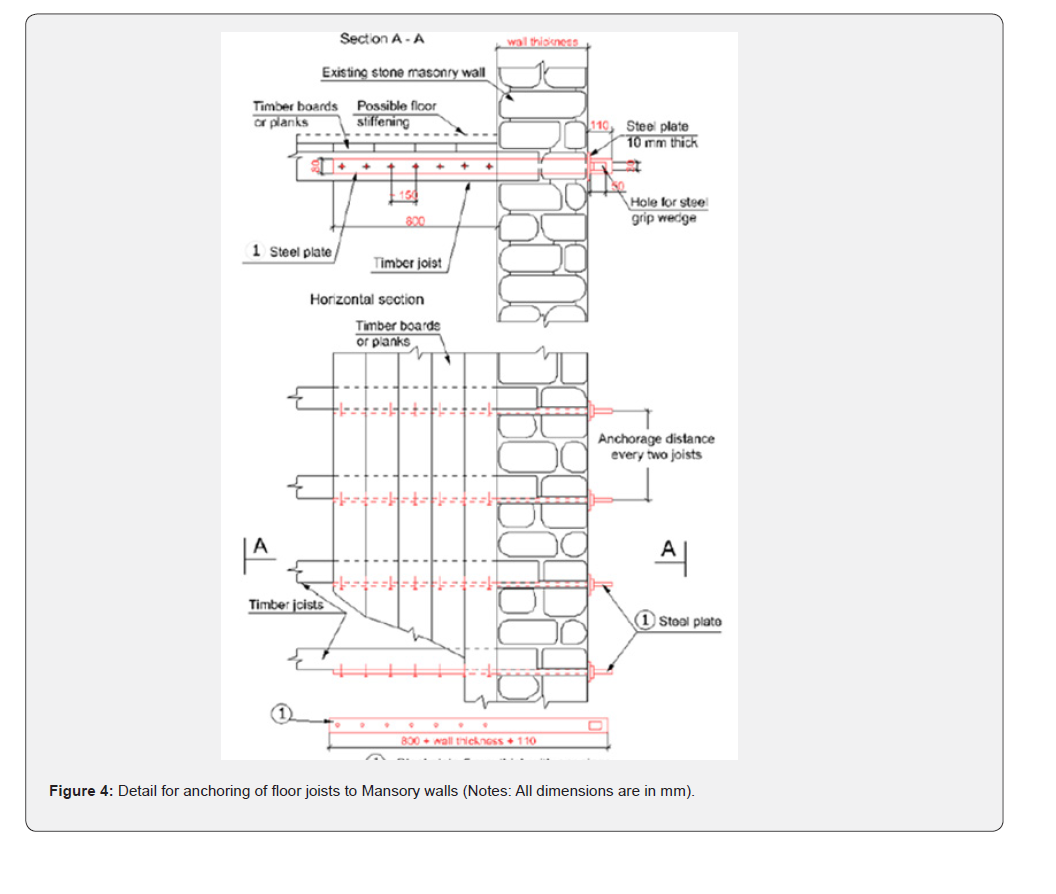

To ensure monolithic behavior (interaction) of the walls and their possible destruction from out-of-plane bending, their anchoring to the floors and roofs is necessary [3]. Anchoring can be done with metal plates, Figure 2, on both sides of the floor beam or only on one side of it when the plate strip (anchoring length) is greater, Figure 3.

In addition to anchoring the walls with wooden floors with

metal plates, in cases where:

i. The distance between the transverse walls is

considerable (L≥7.0m),

ii. anchoring with the existing wooden beams is difficult

due to their depreciation or damage, the full truss with metal

profiles remains the preferred solution, Figure 4. The truss belts

are made with profiles while the diagonals are steel bars with

circular section.

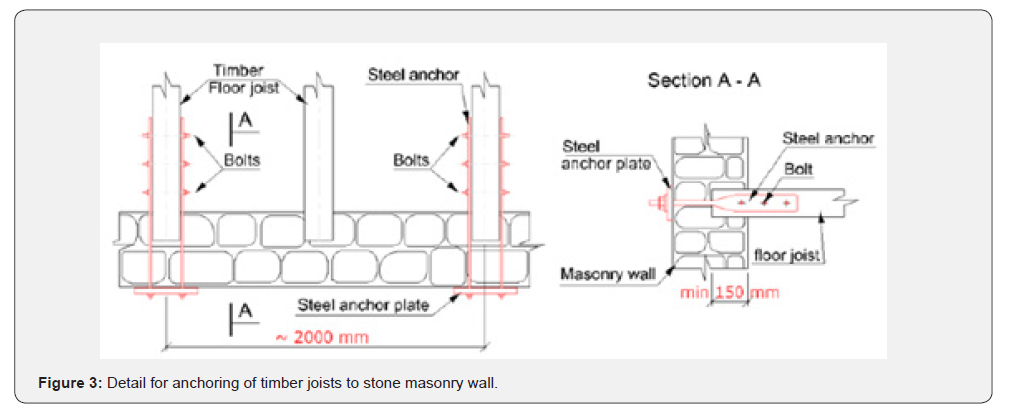

It should be placed at the upper elevation of the existing beams under the wooden floor. The truss placed in the horizontal plane should be anchored to at least three existing walls, to ensure their interaction against the action of the seismic load. The anchoring of the truss to the walls is done with metal anchors fixed with bolts [4]. The techniques for anchoring of loros and roofs to brick/ block are applicable to both brick and stone masonry building Table 1.

In the case of masonry buildings with timber floors tying the walls together at wall intersections, with steel ties, it is not enough to ensure monolithic performance, especially in the case where distance between transverse- cross walls is significant. To reduce uncoupled wall vibrations and prevent possible out-of-plane cracking or failure, the walls need to be anchored along their span with steel connectors to the floor joists [5].

Stiffening of floors and roofs in their plan

To distribute seismic forces in the walls, the floors of the floors and roofs must be rigid in their plan. Fulfilling the rigidity condition makes them behave as rigid diaphragms. Floors/roofs that are semi-flexible or flexible in their plan distribute seismic loads based on the floor/wall stiffness ratios

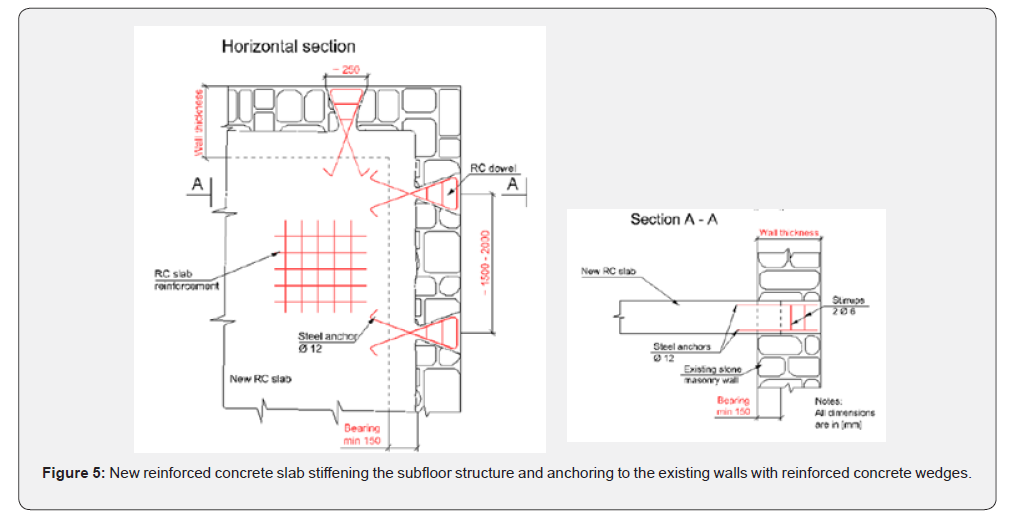

i. To achieve reinforcement, especially in cases where the floor structures of the floors of the floors or roofs are damaged, the best solution is to replace them with monolithic reinforced concrete slabs. At the same time, reinforced concrete connecting strips are also made at the slab level, inside the wall at no less than 1/3 of its width and no less than 15cm. From a structural point of view, the width of the anti-seismic connecting strip is preferably the same as the width of the wall. If it is not possible to make the strip the entire width of the wall, the slab is anchored to the wall with concrete wedges as in Figure 5.

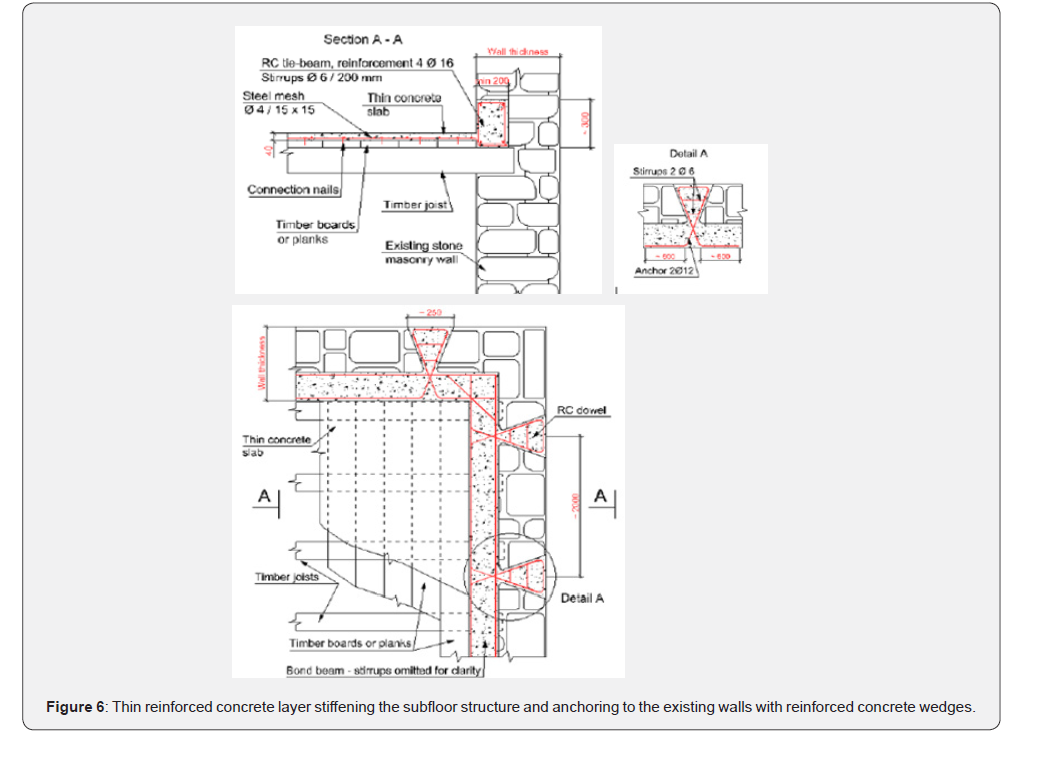

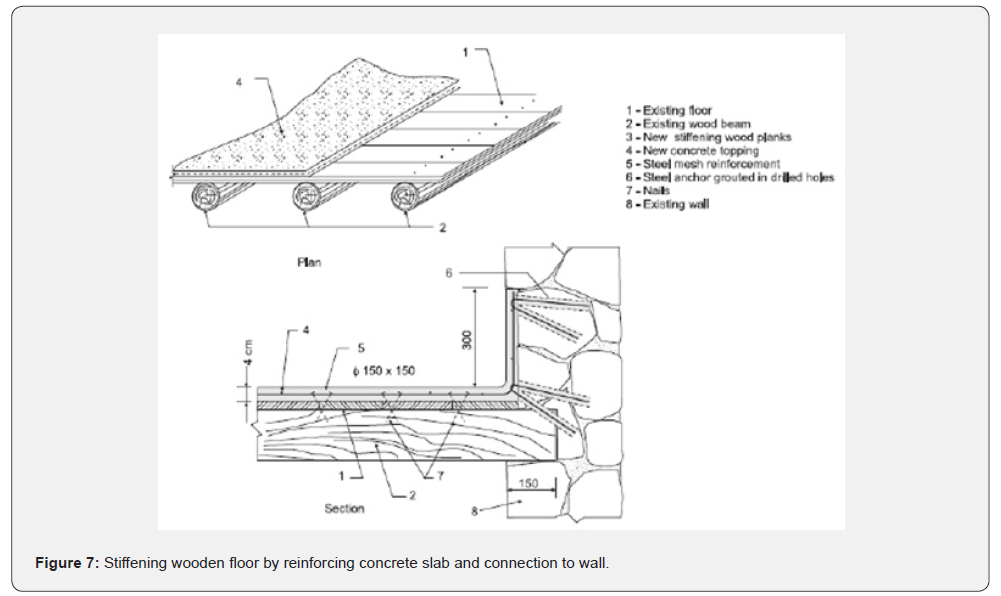

ii. In cases where the existing supporting structure of the floor is undamaged, it is preserved by being stiffened by a thin layer of reinforced concrete (t=3÷5cm) poured over the wooden floor. In this case, the existing wooden floor serves as a formwork for casting the reinforcing reinforced concrete layer. The steel reinforcement grid for the thin stiffening layer must be fixed with nails to the wooden floor as in Figure 6. The connecting strip together with the reinforced concrete anchoring wedges are placed in the space created by carefully removing the existing masonry stones. Instead of a belt, the connection to the wall can also be made with anchor rods fixed by injection into the existing masonry as in Figure 7.

Also, in cases where the existing wooden supporting structure

of the floor is undamaged, stiffening methods less efficient than

the two above methods are:

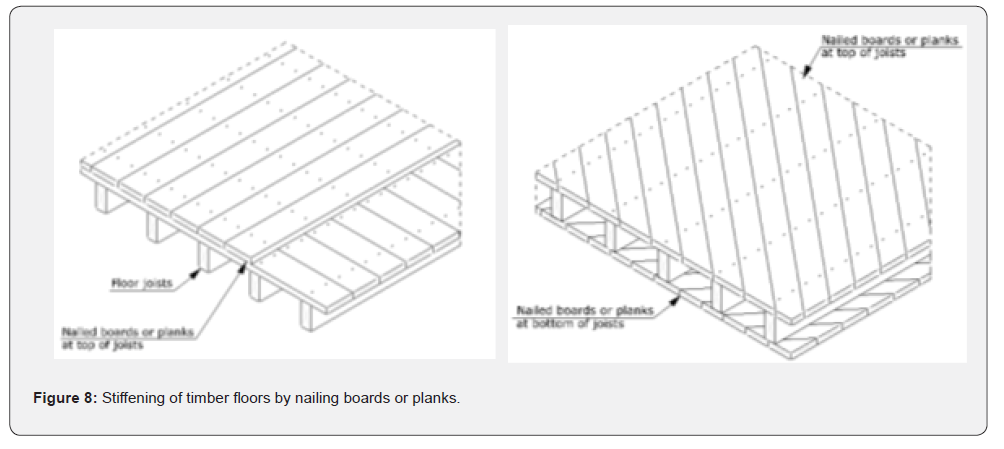

i. Stiffening the floor by placing another layer of wood

fixed with nails on the existing one perpendicular to it Figure 8(a).

ii. Stiffening by placing wood layers in diagonal directions

with elements fixed with nails to the beams of the existing wooden

structure Figure 8(b).

Roof reinforcement

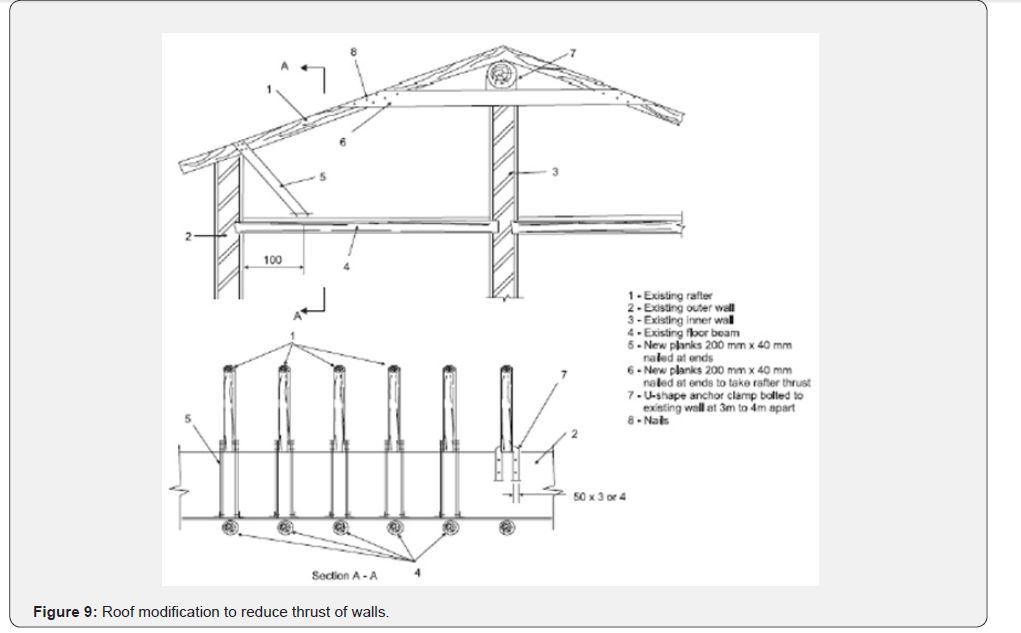

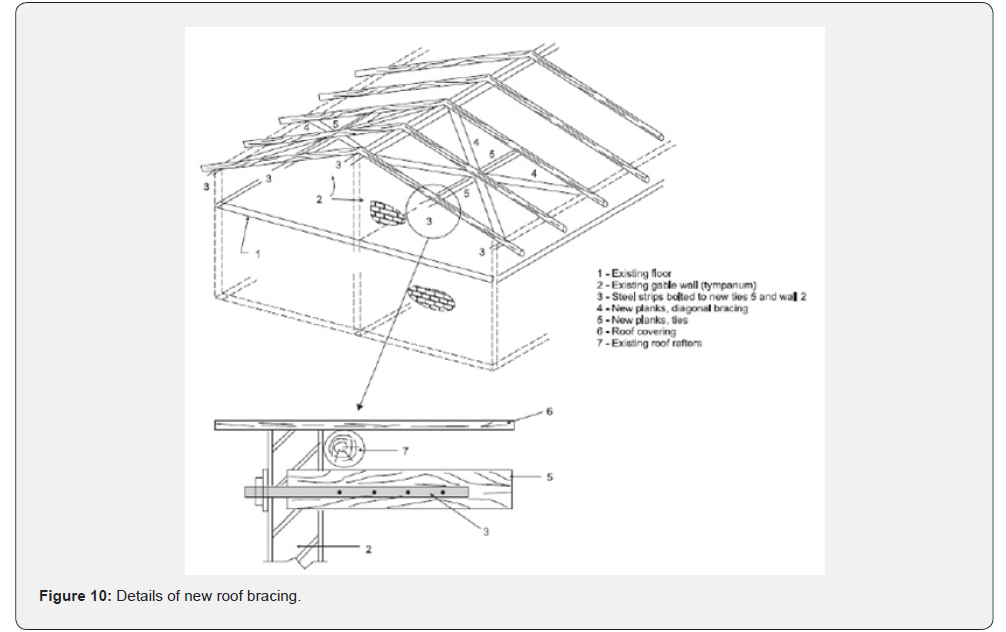

Slightly damaged roof structures should be reinforced by installing additional stiffening elements. In a large part of the roof, it is necessary to apply solutions to reduce thrusts (horizontal thrusts) on the perimeter walls in their static state. As a result of horizontal thrusts, a part of the perimeter walls has lost their verticality by (3÷4) cm. Modifying the static roof truss is one of the options for reducing thrusts as in Figure 8. Installing stiffening elements (wooden ties) as in Figure 9 is the appropriate solution to improve the behavior of the roof under seismic loads. This is for the specific reason that the mass on the roofs of traditional Gjirokaster buildings covered with stone tiles is considerable, consequently the horizontal loads on the roof and on the structure as a whole are high [6].

In cases where wooden roofs are severely damaged (the beams of the supporting structure are damaged by moisture, deformed or destroyed by fire, etc.), it is preferable to rebuild them in the traditional way, adding modifying elements to the static scheme to reduce thrusts and stiffeners (wooden tie rods) for the action of seismic loads [7].

Case Study- Repair of the Wooden Floor at “Myftinia” Building (Heritage Property), Gjirokaster Albania

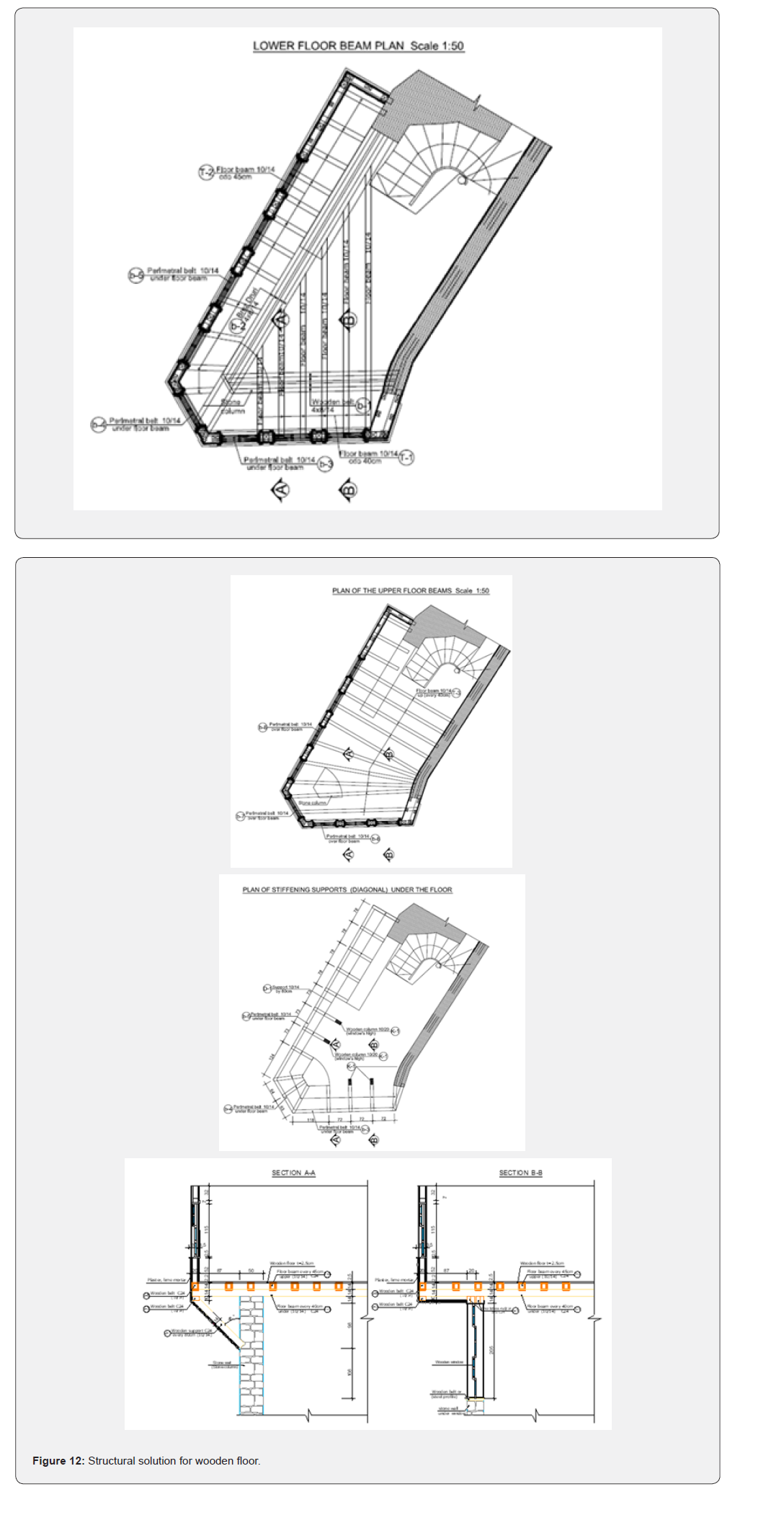

(Figure 10-13 & Table 1)

Conclusion

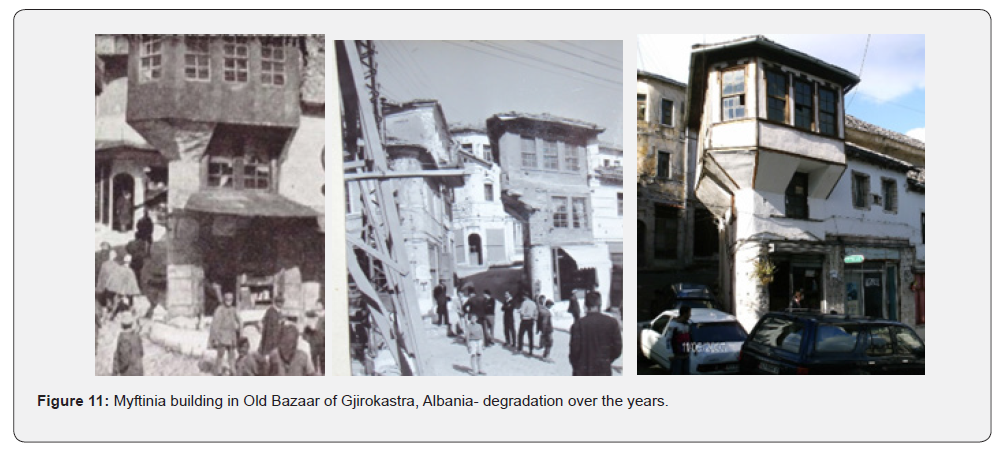

Gjirokastra’s Old Bazaar buildings represent a certain technique and mastery of building traditional structures with limestone masonry of the country, with good resistance characteristics, high durability and affordable cost for the time Figure 10.

Over the years, earthquakes have seriously threatened these structures, considering the morphology of the hill where the buildings are built, which cannot be considered suitable for seismic shaking Figure 11.

The increase in their performance level is based on these basic

criteria:

i. Improving the quality of the damaged material and the

technique used where possible.

ii. Ensuring the structural integrity of buildings through

the creation of the “boxing effect” during seismic shaking.

iii. Realization of connecting rigid bands according to three

orthogonal directions in space.

Based on the assessment of existing wood flooring in historic buildings, total replacement may be considered acceptable when the flooring is beyond reasonable repair or when the extent and distribution of deterioration render limited interventions, such as patching, impractical. Decisions regarding replacement should be guided primarily by the historical significance and integrity of the flooring and the space in which it is located Figure 12.

Where the flooring or space represents a character-defining feature and remains largely intact, replacement materials should closely replicate the original in terms of material, dimensions, pattern, and overall visual appearance. Conversely, in secondary or less significant spaces, or where the historic flooring has been substantially compromised, a lower level of material matching may be acceptable, and the use of substitute flooring materials can be justified without adversely affecting the historic character of the property.

In addition to historical value, practical considerations play a critical role in decision-making. These include the condition, quantity, and location of remaining historic flooring, the feasibility of repair, the extent of irreparable loss, and potential contamination by hazardous materials. Economic and technical constraints-such as compliance with accessibility standards, building codes, fire safety, acoustic performance, or other functional requirementsmay further support the use of substitute materials Figure 13.

Ultimately, any proposed replacement strategy should be supported by a clear justification that demonstrates careful evaluation of heritage significance, physical condition, and feasibility, as well as documentation of alternative treatments that were considered.

In this aspect, the compromise between the structural engineer and the architect or restorer should be based on the principle that if the building is not solid and sustainable, its architectural or historical values are at risk. The laws of gravity, Newton or the mechanics of structures are applied equally to all construction objects, regardless of whether or not they are of architectural, historical, etc. importance.

On the other hand, the structural engineer in his solutions must respect the unique characteristics of these buildings determined by the time in which they were built, in order to have efficient and successful interventions.

References

- (1989) Earthquake Resistant Design Regulations: Seismic Center, Academy of Science of Albania. Department of Design, Ministry of Construction. KTP-N.2-89, Tirana, Albania.

- Hendry AW, Sinha BP, Davies SR (2004) Design of Masonry Structures. Third edition of Load Bearing, University of Edinburgh, UK.

- (2006) International Building Code (IBC), USA.

- European Committee for Standardization (2004) Eurocode 5: Design of timber structures-Part 1-1: General-Common rules and rules for buildings (EN 1995-1-1). CEN.

- Paulay T, Priestley MJN (1992) Seismic Design of Reinforced Concrete and Masonry Buildings. San Diego, USA.

- Sendova V, Apostolska R (2010) Steel, Masonry and Timber Structures. Lecture Notes, Scopje, Macedonia.

- Bozinovski Z (2010) Repair and Strengthening of Mansory Building Structures. Lecture Notes, Scopje, Macedonia.