Abstract

Background: ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction is the most complicated type of myocardial infarction and often requires aggressive and rapid medical treatment. Door-to-balloon time is a quality indicator used to measure the promptness and prognostic outcomes of percutaneous coronary intervention. A delay in door-to-balloon time (>90 minutes) is influenced by several factors, including patient characteristics, healthcare practices, and the characteristics of healthcare workers.

Aim: This study is a part of a large multi-phase study in a major tertiary care hospital in Oman. In this phase, the study aims to explore barriers and challenges that are experienced by healthcare workers in the Emergency Room and Cardiac Catheterisation Laboratory in managing ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction patients’ door-to-balloon time.

Method: Individual semi-structured interviews were conducted to explore the views and experiences of nurses and doctors in the Emergency Room and the Cardiac Catheterisation Laboratory. Interviews were recorded, transcribed, coded, and analysed using reflexive thematic analysis to build and refine a list of themes and subthemes and identify supporting quotes.

Results: Ten nurses and doctors from the Emergency Room and Cardiac Catheterisation Laboratory were interviewed. The findings included three main themes that encompass challenges in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction management: 1) Barriers to success, 2) People factors, and 3) Quality improvement.

Conclusion: The findings of this study suggest quality improvement strategies may include updating protocols on an ongoing basis to consider changes in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction care management to achieve door-to-balloon time <90 minutes.

Keywords: ST elevation Myocardial Infarction; STEMI; Cardiac catheterization; Cardiac catheterization; Percutaneous coronary intervention; PCI; Door to balloon time; Door to balloon in 90 minutes; DTB

Abbreviations: CCL: Cardiac Catheterisation Laboratory; DTB: Door-to-Balloon time; ECG: Electrocardiogram; ER: Emergency Room; PCI: Percutaneous Coronary Intervention; RMIT: Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology University; STEMI: ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction

Introduction

ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) is a serious cardiac emergency that may lead to severe complications and requires aggressive and rapid medical treatment [1]. It is marked by an elevation in the ST segment on an electrocardiogram (ECG), caused when a blood clot completely blocks a coronary artery where the remission depends on how long it takes to re-perfuse the affected tissue [2]. The longer it takes for a patient with a STEMI to be re-perfused, the more likely they are to experience complications and death [3]. The time interval in STEMI management is known as door-to-balloon time (DTB).

It is defined as the interval from the arrival of patients with chest pain at the hospital door to the first balloon inflation or percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) undertaken to restore perfusion [4]. DTB time is a quality indicator used to measure the promptness and the prognostic outcomes of the PCI [5]. National guidelines such as The American Heart Association for STEMI across many countries recommend a DTB time of less than 90 minutes [6]. Despite the recommendation of less than 90 minutes, several studies revealed that a delay in DTB time is common and can be influenced by many factors including patient factors [5], healthcare workers’ characteristics [3], and healthcare setting factors [7].

Similarly, Emergency Room (ER) nurses and doctors identified three major barriers related to the healthcare workers’ characteristics and healthcare setting that contributed to delayed DTB: 1) Processes, 2) Communications, and 3) Resources [8]. In another qualitative study, the participants revealed several factors attributed to the delays in DTB time delay in diagnosing asymptomatic patients, a paper-based ECG not integrated into the electronic medical record system, and limitations on resources during non-working hours [9]. A questionnaire revealed the perceptions of the emergency medical professionals about the factors leading to delays in DTB time and showed a shortage in the number of staff, beds, ECG machines, and factors related to effective communication like lack of standardised protocols [10].

Statistical evidence indicates that multiple factors have caused delays in DTB time in various countries. In China, a 123-minute delay in DTB time was associated with a 20-minute delay in consent time [11]. In Thailand, a delay of 117 minutes of DTB time was associated with factors such as the accuracy of patient triage and presentation to the ER during non-working hours [12]. In India, the delay in DTB time of more than 90 minutes was associated with patient education and ability to recognize STEMI symptoms and the arrangement of transport to the hospital [13].

Aim of the Study

This study aimed to explore barriers and challenges that are experienced by healthcare workers in the Emergency Room (ER) and Cardiac Catheterisation Laboratory (CCL) in managing STEMI patients’ DTB time in Oman.

Methods

This study is part of a larger multi-phase study and in this phase, the authors aimed to explore barriers and challenges that are experienced by healthcare workers in ER and CCL in managing STEMI patients’ DTB time. Semi-structured individual faceto- face interviews were conducted with nurses and doctors working in ER and CCL at a major hospital in Oman. Each interview duration lasted from half an hour to one hour. The interview questions for this study involved three parts. The first part focused on demographic details and years of experience in STEMI management and challenges in managing STEMI during the participant’s career. The second part of the interview covered challenges related to DTB time. The interview questions included DTB delay-associated factors.

During the final part of the interview, participants were asked about improvement plans developed in their department or at organisational level. The interview schedule is included in Table 1. The qualitative data were analysed and interpreted using reflexive thematic analysis as described by Braun and Clarke [14], as a method of reorganising, analysing, and reporting themes generated from a set of data. The thematic analysis included steps of transcribing the audio-recorded data, creating a set of initial codes, assembling the codes with supporting data, grouping codes into themes, revising the themes, and finally writing the narrative report [14]. This study was approved by the University Human Research Ethics Board (approval number 25548) as well as approved by the Research and Study Centre at the Ministry of Health, Oman.

Results

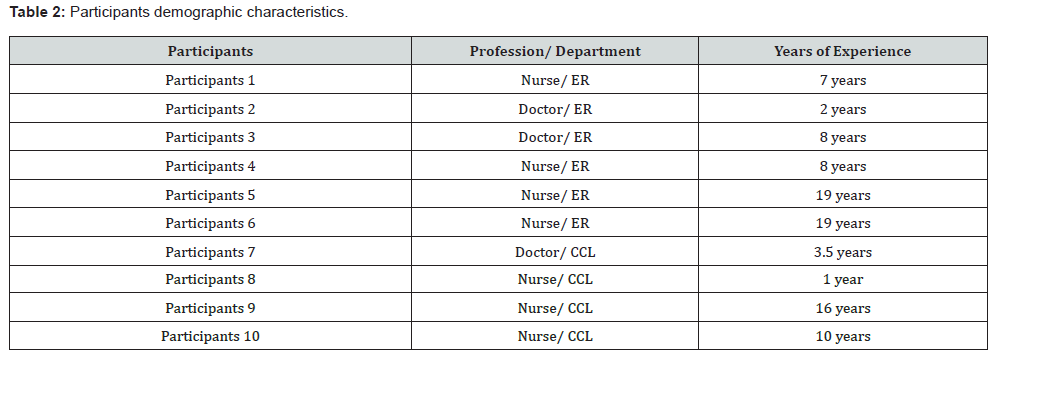

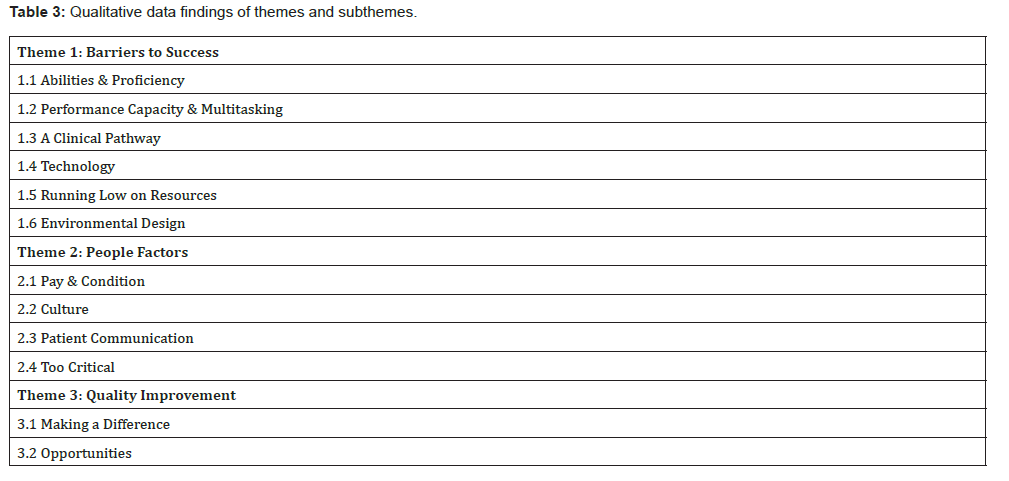

Individual Interviews were conducted with a total of 10 staff from ER and CCL as outlined in Table 2. The findings included three main themes which encompass challenges and barriers in STEMI management. The three themes were Barriers to Success, People Factors, and Quality Improvement. Each theme had subthemes illustrated in Table 3:

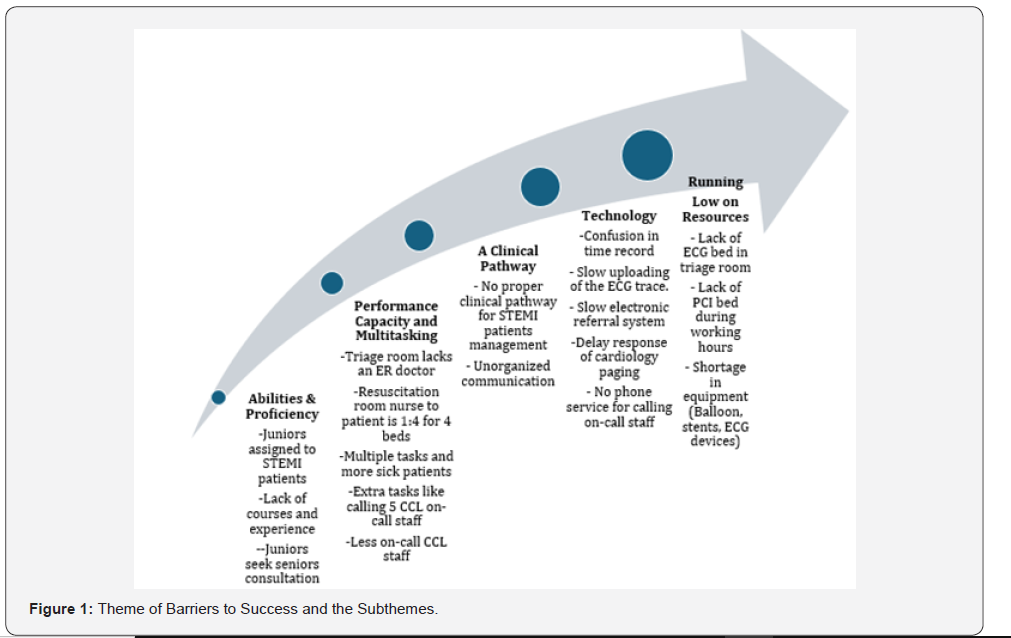

Theme One: Barriers to Success

Participants expressed barriers to success in managing the STEMI cases within the 90-minute DTB timeframe. The first theme of Barriers to Success included six sub-themes Abilities & Proficiency, Performance Capacity & Multitasking, A Clinical Pathway, Technology, Running on Low Resources, and Environmental Design are summarised in Figure 1.

Abilities & Proficiency

In the ER, participants in this study expressed that triage nurses and doctors should be seniors and certified in the ECG interpretation course.

“Most of the staff completed the triage and also ECG course for those who are sitting in the primary triage.” (ER nurse participant 5).

“They (the triage nurses) have the ECG course, and they should be senior.” (ER nurse participant 4).

ER doctor participant 3 rationalised that seniors are assigned to the triage room because they have more experience reading the ECG rhythms.

“This is very critical. Okay. Availability of staff nurse and her degree, for example, senior staff nurses with us, they know, this ECG is abnormal. She can realise it. Yeah, she can realise this is something abnormal”.

Participants in this study expressed shortages in the number of healthcare providers and attributed this to the delay in DTB time.

Note: STEMI: ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction, DTB: Door to Balloon.

Note: ER: Emergency Room, CCL: Cardiac catheterisation Laboratory.

Nurse participants commented on the loss of nursing staff.

“We have now a lot of resignations from the staff nurses, 50% of our staff now are juniors.” (ER participant 4)

“Staff are leaving for the good opportunities in different countries.” (ER nurse participant 1)

Due to the shortage, the impact of having juniors assess patients twice or seek further consultation contributed to the delay, which could have been avoided if the person allocated the task had been appropriately experienced.

ER doctor participant 3 expressed that junior doctors require senior doctor consultation to confirm STEMI which consumes time.

“If seen (STEMI case) by junior doctors, they have to discuss with the senior first and then to activate, so that they will take time.”

ER doctor participant 2 added that ECG interpretation waits until the senior doctor arrives which further delays the patient’s stay in the ER.

“Juniors need to be supervised by a senior emergency physician, but there is again a delay in interpreting the ECG.”

Participants expressed that sometimes it is difficult to diagnose STEMI as the symptoms of the patients are not clear or do not completely indicate STEMI.

“Sometimes they give different symptoms in the primary triage, when they reach the secondary triage, they will give more details about the chest pain.” (ER doctor participant 2).

Participants in this study expressed that STEMI diagnosis is not always recognised in the ECG rhythms.

ER doctor participant 3 stated that some ECGs are initially normal rhythms and when the patient is moved to a less critical area STEMI is identified.

“Patients come with chest pain; ECG found normal in triage. He will go to the treatment room to be seen by the junior doctors and by the time ECG will start to show changes.”

ER nurse participant 4 stated:

“For them (the junior doctors), it is not easy to read the ECG, unless the senior doctor comes later and discovers as STEMI, there will be delay, it happened so many times.”

ER doctor participant 2 added that this process gets further delayed as some cardiologists perform other clinical investigations to confirm the STEMI.

“Some cardiologists take time to assess the patient, to do Echo, to discuss with the consultant. So, all of these will delay CCL activation.”

In CCL, participants raised concerns about considering less experienced staff as senior staff.

“Staff with one year experience we consider them as senior, 90%-95% of the staff are seniors.” (CCL nurse participant 10)

“There is one senior who knows everything and has the experience, and two other nurses one is a junior, and the other is a semi-senior who is less than one year. The senior nurse can’t scrub in case she is required for any emergency.” (CCL nurse participant 4)

Cardiac catheterisation courses of four months are necessary for the junior nurses to work inside the laboratory room and do on-calls. Participants expressed that junior staff nurses are still not ready and lack the skills to manage STEMI cases during the PCI procedure. Juniors who are on-call had only a short preparation course due to the lack of time to train them.

“Juniors are trained for four months to start on-call.” (CCL nurse participant 8)

“I can train them for months and months, but I don’t have that time, then I will just have to throw them in the steady calls while they are not up to the level of experience and skills.” (CCL doctor participant 7).

CCL nurse participant 7 revealed that the management of STEMI cases by the on-call team requires a standard number of two technicians and three nurses. However, CCL nurse participant 9 stated with the shortage, the team can function with a smaller number of staff.

“Sometimes we can work with two staff if the patient is stable, but if the patient is unstable, we need to call staff to help.”

The availability of junior staff nurses was sometimes an issue with advanced skills and performance issues that affected the DTB time duration during procedures:

“It’ll effect of course the procedure because she (the junior nurse) will be slow. She’ll be still not very good at everything. So, sometimes we need to push ourselves inside the procedure and keep her outside.” (CCL nurse participant 9).

During non-working hours, the CCL staff nurses stay on-call outside the hospital. The unavailability of the on-call team in the hospital grounds is a factor that delays DTB time. CCL nurse participant 9 stated that it takes a long duration of time for the nurses to reach the hospital once they are called for PCI.

“They are doing on-calls, so some of them are far away from the hospital. They will take 30 minutes sometimes more than 30 minutes to come to the hospital”.

Performance Capacity & Multitasking

Participants expressed the effect of multiple clinical tasks that should be carried out for the STEMI case in a limited time impacting DTB time. At the triage area, the patient’s first station in the ER, DTB time is affected due to the triage nurses’ involvement in other tasks. ER doctor participant 3 expressed that it is not possible to prioritise or even recognise the STEMI cases due to the multitasks that must be carried out in the triage room.

“When you are sitting in the triage room you have multiple things to do, you will have a patient, and sometimes a relative ask about something”.

“The staff put the ECG in my hand, and I did not realise it was an ECG because there were multiple patients around me…. Oh my god it was a STEMI I don’t know yet”.

Similarly, ER nurse participant 4 expressed that with multiple patients they require help recording the ECG.

“The staff cannot go and do the ECG for the patient, because she has a lot of patients. She will call the in charge to do the ECG, it will also take time”.

Clinical assignments to more than one task for more than one patient sometimes occur where one staff member is covering more than one area of responsibility. This was another example of staff being overwhelmed with tasks that led to delays in DTB time.

“One staff will be taking primary triage and secondary triage. Two areas of allocation. So, this will delay STEMI patient who is waiting in primary triage as the nurse is busy in secondary triage with other patients like for cannulation.” (ER nurse participant 6)

ER doctor participant 3 expressed that ER doctors are also responsible for seeing other patients in the treatment room.

“There are some who are in triage, he has to cover sometimes inside (treatment room). I mean he has to see other patients, not only patients but also to carry multitasks due to the shortage”. Likewise expressed by ER nurse participant 4, that it takes time for the ER doctors to see the ECG as they are busy with other tasks or other patients.

“They will be busy examining other patients. So, they will take five to ten minutes until they see the ECG if STEMI”.

Once the patient is diagnosed with STEMI and moved to the resuscitation room, the participants expressed the multiple tasks that should be carried out rapidly. ER nurse participant 6 expressed that the patient requires many procedures that are carried out by only one nurse.

“The nurse has to prepare the patient from scratch, cannulation, shaving, consent, medication, X-ray, invasive procedures, and intubation. Unfortunately, we have only two staff covering four patients each in the resuscitation room.”

“Because STEMI is coming to the resuscitation room, it needs even two or three staff nurses.” (ER doctor participant 2)

The impact of the shortage of staff nurses in the ER was explained by ER nurse participant 4 which led to assigning more patients per nurse in the resuscitation room.

“The resuscitation room should be one to one (one nurse for one patient), but in our emergency department it is one (nurse) to three or sometimes one to four or five patients.”

Besides patient preparation, the nurses in the ER expressed dissatisfaction with performing extra tasks like calling CCL on-call staff during non-working hours. ER nurse participant 4 explained the long process of getting the CCL on-call staff phone numbers from the system.

“We have to go to the computer, there will be a schedule, date, name, and phone number of the CCL staff, and we have to call them one by one.”

ER nurse participant 1 concurred and considered this an obstacle that causes delays in DTB time.

“In fact, I can add this to the barriers that cause delay because we have to call five staff, technicians, and nurses.”

“Instead of spending time calling (the on-call team), I can accelerate preparing the patient.”

A Clinical Pathway

In this study, the participants revealed that one of the associated challenges that delayed DTB time was the lack of a clinical pathway for STEMI. The clinical pathway is a clinical management plan for the STEMI patient. ER doctor participant 2 explained that once the STEMI diagnosis is confirmed, no guideline clarifies under whose care the patient should go while in the ER.

“Either we will take the responsibility of the patient in the triage room and call the cardiology team to stay with the patient or we will call the in-charge doctor in ER to send somebody to resuscitation room to assess the patient.”

“Anyone from the emergency, any senior emergency physician even a senior resident can call the cardiologist to activate the cath lab (CCL).”

The CCL nurse participant 9 expressed that sometimes the STEMI cases are delayed as they don’t know who they called in the ER to shift the patient.

“We call them (ER), and we don’t know who receives the call. We don’t take the names. If they delay, we will call them again and they tell us you didn’t call!”

Technology

Participants in this study expressed the technological challenges associated with the delay of DTB time. The time record of the clinical intervention intervals was measured using different devices to identify progress like smartphones, computers, or wall clocks. ER nurse participant 4 expressed that not all nurses follow the same device in the time record.

“Sometimes when I do ECG for the patient (in triage room), the time for ECG done will be printed by machine itself. Okay, and when the patient is seen by the cardiologist (inside the treatment room), the nurses might follow the time of the wall clock”.

The CCL nurse participant 10 described the process in CCL to record the clinical intervention intervals.

“We follow the time from our computer in the Al Shifa system (the medical electronic record system), because sometimes the watch (wall clock), is like five minutes less or more.”

To correct the confusion in the time record, ER nurse participant 1 expressed that they countercheck the time verbally.

“We have to say to the people who receive the call the time. For example, the time now is 11.15, so let him (the call responder) know the time is 11.15.”

Uploading the ECG in the medical electronic system was another technological challenge that was associated with the delay of the DTB time. ER doctor participant 2 expressed frustration when ECG uploading is delayed.

“But sometimes we will get delays in uploading the ECG in the Al Shifa system (the medical electronic record system) and the cardiology needs to come to the ER to see the ECG.”

A lack of ECG machines in the ER was identified by ER nurse participant 4.

“We have only one ECG machine used for normal resuscitation and the isolation resuscitation room.”

Informing the cardiologist about the STEMI case in the ER requires an electronic referral through the electronic medical record system, however, ER doctor participant 2 explained that the referral is not visible immediately to the cardiologist.

“Referral will not be shown immediately to the cardiology, it will take time.”

The delay of cardiology arrival to the ER was expressed by the ER doctor participant 3 as also associated with the paging system; one pager covers all calls including the ER calls for STEMI.

“When we call the cardiologist, they don’t answer, maybe he is busy, he doesn’t know if it is a STEMI call just a simple case in the ER.”

Due to the unavailability of phone service for calling staff phones from the resuscitation room, ER nurse participant 4 explained that they had to spend more time saving CCL on-call staff’s phone numbers in their phones and then calling them which delayed the DTB time.

“Just I will see the numbers in the system, save them in my phone, and call them one by one.”

CCL nurse participant 9 expressed that sometimes ER nurses do not dial the right phone numbers and call someone else or forget to call one of the on-call staff, which again delays the arrival of the on-call staff to the hospital from the time being called.

“They (ER nurses) will call somebody else not from the group, maybe they dialed the wrong number by mistake.”

“Sometimes they will forget to call one of the team members and that will affect also the arrival timing.”

Running Low on Resources

The sub-theme Running Low on Resources encompasses all the aspects of STEMI care participants felt were impacted by insufficient resources. Participants in this study expressed shortages in medical equipment like beds and ECG machines and attributed this to the delay in DTB time. In the ER, participants revealed that the availability of the ECG bed in the triage room impacts the door to ECG time. ER nurse participant 5 noted the triage room ECG bed is used for all types of patients.

“Only one bed is allocated for ECG for all patients in the triage room.”

The impact means staff need to find another location for overflow on an ad hoc basis. The availability of beds is further exacerbated by delays in transferring patients who need admission.

“If there is another patient, we will quickly take the patient to the resuscitation room for ECG.”

“Most of the days we have patients who are supposed to be admitted and they are kept in the emergency department, this affects the new cases as all beds will be occupied.” (ER doctor participant 3)

Similarly, in CCL, during working hours when there is a STEMI case, the CCL team must evacuate one elective case from one of the laboratory rooms to receive the STEMI case. CCL nurse participant 9 stated that they empty the room if the patient is stable.

“We should make sure that one room is empty, if a patient is on a table, they can pull him out if he is stable enough to stop the procedure to bring the PCI case.”

Further to the availability of the laboratory room for emergency PCI, CCL participants expressed frustration with finding items during the procedure as they were not available. CCL nurse participant 10 expressed frustration about time lost setting up procedures with equipment shortages due to delayed delivery during the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“We had issues with the stent and balloon, we didn’t have enough, and we didn’t have the right sizes.”

Similarly, CCL nurse participant 9 identified shortages in equipment as an issue and attributed it to other causes.

“We have a shortage of balloons and stents. Okay. And that’s because of the increase in the patients’ numbers. There was a problem between the companies and administration, and they took more than six months to deliver the items.”

“We will wait to search for that stent, it will take another five minutes.” (CCL nurse participant 9).

Environmental Design

The subtheme of Environmental Design encompasses challenges in the hospital building design in which ER is in the hospital’s main building and CCL is in another building. Several participants indicated this as a challenge due to the long walking distances of around 1000 meters between the two departments. ER nurse participant 5 expressed that the journey from ER to CCL is not structured for easy movement as it consists of many corridors and units to pass through.

“The journey is also very difficult, too many blocks (corridors) on the way.”

“It is a long distance (from ER to CCL) of around one kilometer.”

“Pushing (the patient) full of equipment, monitor, oxygen, and patient and running for one kilometer.”

ER nurse participant 6 explained that moving the patients between these two departments is an exhausting procedure.

“Sometimes the patient is heavy. So, we have to push the patient, and we are running to go there.”

Similarly, the participants expressed that it takes a long time for the cardiologist to reach the ER when they are called STEMI patients. ER nurse participant 5 expressed that STEMI patients are delayed mainly due to this factor.

“The cause of the delay is mainly the cardiologist, it will take time to walk from the cardiac center to the ER, it is a long distance.”

Unstable STEMI cases are further delayed as they require to be stabilised in the ER before moving for PCI. CCL doctor participant 7 expressed that along with the time spent in stabilising the critical cases, the long distance between the two departments delays further patient transfer to CCL and DTB time.

“If the patient is unstable, you cannot push him for five to 10 minutes is too long. So, you have to stabilise the patient. Yeah. So, you really need to make sure that the patient is stable enough before you can shift. And that sometimes can cause delay.”

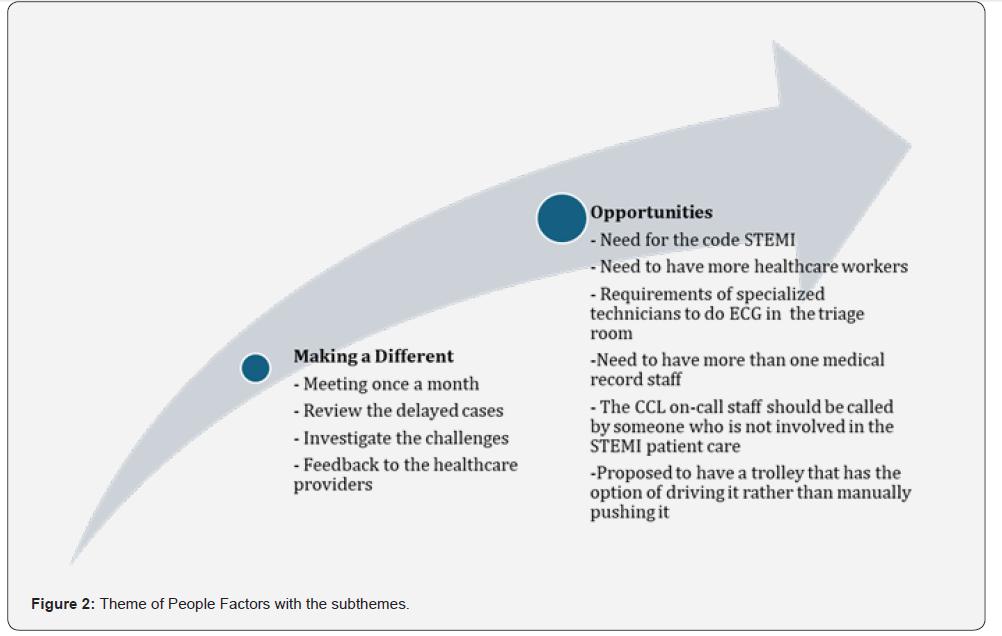

Theme Two: People Factors

Participants in this study revealed challenging factors that contributed to the delay of DTB time that are related to people factors that impact healthcare workers and patients. The people’s factors in this theme are referred to as any factor related to the well-being and satisfaction of the healthcare workers and the patients. Healthcare workers expressed work-related challenges in areas of work conditions and payment. The participants also described cultural impact, patient communication with the care provider, and patients’ critical condition as factors. The subthemes are summarised in Figure 2.

Pay & Condition

The participants expressed dissatisfaction with the workload and compared it with the salary they received. The participants revealed that due to work-related stress, many healthcare workers left their jobs, affecting the staff census and ultimately DTB time. CCL nurse participant 9 stated that they are not paid for the oncall days, which has affected the staff turnover.

“The seniors are transferring and resigning because of this stress (unpaid on-call salaries).”

CCL doctor participant 7 added that the shortage of healthcare workers impacted on the welfare and the rest days.

“People are asking for their leaves, but they cannot go because of shortage.”

CCL nurse participant 9 added that the CCL staff are overwhelmed with the workload, but they force themselves to work faster when they receive STEMI cases.

“What we are doing now, we are trying to squeeze ourselves, squeeze the doctor and the staff to limit the time between the door to balloon.”

The participant added that the on-call system does not compensate them for on-call hours but only counts the hours they are required to replace. Also, the participants expressed disappointment that they remained at home during the on-call till the CCL activation call.

“The problem is they are not giving us salary allowance or oncall allowance. And we are working after working hours. We are only taking the hours bonus. The off days, they are not replacing them. They count the hours, whatever you are on call, you should stay at home. You should not go out of the home”.

“We will stay full day If they did not call us, we would not have anything, this is a waste of our life”. (CCL participant 9)

Culture

Participants in this study expressed cultural issues related to STEMI patients encountered by the healthcare providers as challenges that impacted the DTB. ER nurse participant 6 identified gender and its relation to the provided care.

“If the patient is a male patient. So, most of our staff are female also. So sometimes we have to look for male staff to do the shaving also, sometimes there is no male staff. So, we have to call the male medical orderly.”

Likewise, CCL doctor participant 7 revealed that some female patients have cultural restrictions on exposing their body to male care providers and they request only female staff.

” The female patients refuse to give consent for the male nurse to expose and clean. So, sometimes we have to wait for the female nurse to arrive.”

The participant added another cultural issue of consent that impacts DTB time. In Oman, many patients do not make decisions or sign a document unless the next of kin or the most responsible family member is available.

“A lot of our patients, unfortunately, especially females and elderly don’t want to give the consent themselves. They want to wait for family members to come to consent.” (CCL doctor participant 7).

“But sometimes we get stuck in some cases where the patient is refusing to sign consent and wait for his son who is on the way. But then he (the son) may take, uh, you know, 30 minutes, 40 minutes, whatever to arrive. So that problem is also there.” (CCL doctor participant 7).

Patient Communication

Communication with STEMI patients was identified as a challenge by the participants that impacted DTB time. The native language in Oman is the Arabic language and the English language is also used in the health care setting. However, there are many other languages in Oman as it has a diverse culture.

“Sometimes the language barrier is there. The patient will not be able to express his pain, for example, he will not tell them chest pain.” (ER doctor participant 3).

The importance of reassuring and communicating with STEMI patients an important aspect of avoiding delays in DTB time. This is because STEMI patients experience a priority of care in acute settings like the resuscitation room. This causes stress and anxiety and delays the procedure further. CCL nurse participant 10 shared her experience of how the patients feel frightened as they are not aware of what is going to happen to them.

“Most of the patients will be terrified, they think the cardiac catheterisation laboratory is a cardiac surgery place and they think that we will open their chest.”

The participant further expressed the importance of communicating with patients and reassuring them to reduce anxiousness and make the patients feel more secure during the procedure.

“We communicate with the patient; we explain to them what we are doing during the procedure… we will tell the patient that we will go through his hand, and we need to clean this area, so he will not be afraid.” (CCL nurse participant 10)

Theme Three: Quality Improvement

The quality improvement theme is divided into two subthemes making a difference which is about the changes that have taken place and opportunities which is about suggested changes. The sub-themes are summarised in Figure 3.

Making a Difference

Participants expressed the changes they have implemented to overcome the challenges encountered to improve DTB time. ER nurse participant 1 stated that healthcare providers from both departments ER and CCL meet once a month to review cases

“Every month each department presents their assignments, tasks, and failure, and gives feedback of the meeting to the staff.”

CCL doctor participant 7 stated that the meetings’ outcomes are taken by the teams of both departments to give feedback to the healthcare providers.

“This feedback loop, is actually what we create out of these improvements…people who are saying we are good, we show them for example, the time was one hundred minutes instead of 90 minutes.”

The participant added that the workflow for the STEMI patients was improved when both department teams investigated the challenges.

“The task force committee is one of the initiatives that helped to improve DTB time by creating a STEMI pathway in the ER because what used to happen was that patients (STEMI) were treated according to who arrived first would be treated first.”

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the creation of a primary triage area before the main triage room for filtering patients according to COVID-19 symptoms was established.

“We had the crisis pandemic COVID-19 during which the primary triage was created and that really was helpful to categorise the patient from the beginning and catch those STEMI patients from the primary triage.” (ER nurse participant 1).

ER doctor participant 2 stated that the availability of an ECG machine inside the triage room helped the nurses to improve door-to-ECG time.

“One thing is doing the ECG from the secondary triage, it (ECG machine) was not there before.” (ER doctor participant 2).

ER doctor participant 3 expressed significant improvement in the door to ECG time.

“I can say in more than 80% of the cases, ECG is done within 10 minutes.”

The availability of the ER physician inside the triage room was recognised by ER doctor Participant 3 as one of the factors that helped in the fast interpretation of the ECG.

“Before there were no doctors in the secondary triage room, only one staff nurse, with all respects, but it is different when we have a doctor in triage who will detect STEMI faster and activate CCL.”

In CCL, the team meeting made changes in the on-call list. CCL doctor participant 7 explained that the new on-call list includes staff who are staying nearby

” So, one thing we did, and we are trying to do it continuously is not to keep people who are living far away in on-call same time”. (CCL doctor participant 7).

Moreover, CCL nurse participant 9 expressed that finding a car park inside the hospital car park was an issue that delayed the staff’s arrival time at CCL.

“The hospital provided a car park for the on-call staff near the cardiac catheterisation laboratory door. We did not have car parking for the on-call staff. It was a problem, because for example during the visiting hours, it was difficult to get a car parking, and at night after 2 am it is scary to park in a far parking”.

Opportunities

Besides the efforts that have been implemented, the participants suggested further changes. Participants expressed the need for a code STEMI system. ER doctor participant 2 rationalised the need for the code STEMI as all the team being alerted at the same time.

“If we have a code for STEMI cases that emergency will activate this code. Cardiology will be in, and the technician and nursing in the cath lab will be in. So, this will, I think, make the other parts easier or the whole process will be easier”.

Participants expressed the need to have more healthcare workers to shorten the DTB time. ER nurse participant 6 expressed:

“The staff: patient ratio in the resuscitation room should be one-to-one because it’s a critical area”.

The participant added the hospital should provide more staff during the peak hours in the ER.

“The peak hours of emergency will be like 11 to 12 noon. So, so many people (patients) are there at that time, so we need somebody to do the ECG for the patients”.

Furthermore, the participant specified the requirement of specialised technicians to do the ECG.

“I think there should be one ECG technician to be there in the triage area because most of the patients are complaining of chest pain also. So, to keep one ECG technician there it will be easier for us”. (ER nurse participant 6).

ER doctor participant 3 expressed the need to have more than one member of staff in the registration office so they can cover the job if one of them is not available.

“To have more than one person in registration if one takes a break the other one will be there, as this will play out in delay”.

ER nurse participant 5 proposed that CCL on-call staff should be called by someone who is not involved in the care of STEMI patients, so ER staff focus more on STEMI patient preparation.

“We can inform duty nursing officers, they respond very fast, they can contact the cardiac catheterisation laboratory staff”.

Due to the long distance between ER and CCL, ER nurse participant 1 proposed to have a transporting trolley that has the option of driving it rather than pushing the bed.

“So, if there is trolley auto drive it will help the staff instead of pushing full of equipment monitor, oxygen, and patient and running for one kilometer”.

Discussion

The findings of this study highlight challenges confronting nurses and doctors working in ER and CCL. The participants in this study related DTB time to insufficient proficiency of staff. The employees’ performance can be measured by factors such as seniority, role, or effort of each employee. Equitable operational policies mean incorporating employee contributions into decision-making outcomes [15]. In the opinion of the current study’s participants, understaffing led to the allocation of junior nurses and doctors in critical care settings. In a qualitative study, the outcome of being understaffed resulted in a higher presence of inexperienced junior staff, impacting the effective delivery of care [16].

To ensure effective management, rapid recognition, and triage, are essential for immediate clinical diagnosis when a STEMI is suspected [17]. According to the participants of this study, juniors’ skills in assessing STEMI patients were one of the challenges, since they lacked experience and sought senior consultation for STEMI diagnosis. Additionally, STEMI patients like women and diabetics might present with atypical symptoms like gastric pain which confuse further the junior doctors in the fast recognition of STEMI cases [18]. An online survey outcome revealed that 19% of the juniors had low confidence in the assessment of the atypical symptoms and reading difficult ECG patterns [19].

The participants revealed that adequate staffing is crucial for ensuring effective STEMI care delivery as well as improving key indicators of ER and CCL throughput. Oman faces a shortage of nurses. Even though Oman produces a substantial number of diploma-level nurses each year, expatriate nurses continue to be in high demand in the service sector [20]. In comparison to other professions in the country, nurses receive lower salaries than nurses in neighboring countries. This presents a problem of migration, particularly for foreign nurses who resign as soon as they are offered better employment opportunities in neighboring countries which creates sustainability impacts on the quality of care [20].

The participants in this study reported that nurses and doctors in the ER are overwhelmed with multiple tasks that contribute to delays in DTB time. The clinical assessment of the STEMI patient requires multiple actions due to the time limit to reperfusion of the cardiac tissues. It involves a 12-lead ECG within the first 10 minutes of patient contact with the medical team [21], a holistic clinical history, and a complete cardiovascular workup to elucidate the related risk factors [18]. However, more than 18% of ER physicians’ working time is found to be engaged in performing other tasks in the ER [22]. The concept of multitasking refers to the alternation of tasks or the parallel execution of tasks i.e., rapid succession of tasks [23], or a condition in which the demand for services exceeds the capacity of the service provider [24].

Examples of multiple tasking: a clinician is performing diagnostic procedures on a patient while simultaneously documenting and conversing on the phone [22]. As a result of interruptions in the emergency room, multitasking leads to time loss and may also result in medical errors [25] and is a direct cause of delaying treatment time [26] or the patient leaving without being seen [24]. The clinical pathway suggested in this study would facilitate STEMI care coordination between ER physicians and cardiologists. The participants reported that patients stay in the ER either under the care of the ER team or cardiologist depending on the team agreement on duty.

Hence, this was reported as a contributing factor that led to a delay in DTB time as the decision-making pathway was not clear. Studies show that using standardised protocols has decreased the time to reperfusion and improved coordination between emergency departments and cardiac catheterisation laboratories [27,28]. The Comprehensive STEMI Protocol allows emergency physicians to activate CCL without cardiology consultation which reduced DTB time from 114 minutes to 97 minutes [28]. Despite the reduction in DTB time, however, activating CCL without cardiologist consultation might result in false positive activations. This also would contribute to an increase in the workload and staff fatigue that ultimately prolongs DTB time [27].

The development of a standardised STEMI care pathway that specifies the role of each caregiver would enhance teamwork and communication to attain the DTB time in less than 90 minutes. Fast track policy as another example of the clinical pathway for chest pain patients in ER was evaluated in the study by [29]. The study proposed fast management for all patients who presented with chest pain with a clear pathway and role assignment for all healthcare providers. This resulted in significant improvement in DTB time with an increase of 47.78% of patients receiving PCI within 90 minutes. Considering the hospital in this study is PCIequipped, the standardised STEMI care pathway should involve a level five facility of care for all chest pain patients, or in other words the hospital should be skilled enough to manage STEMI patients quickly with appropriate reperfusion therapy [30].

The level five facility of care includes adopting a formal STEMI care model with a clear guideline of what needs to be done in different settings with varying resources, setting standard care, triage, and evidence-based transfer protocols [30]. It is imperative that STEMI systems recognise the nature of resources available and develop protocols that are designed to be effective. In this study, the participants reported the impact of resource unavailability on the process of STEMI care. The lack of resources reported by the participants of this study is a lack of beds and equipment like stents, a standardised time recording device, an ineffective process of ECG sharing, a slow electronic referral system, and a lack of pagers and phones. Studies have shown that shortages of resources contributed to increased patient waiting time in the ER for admission which consequently resulted in dissatisfaction among nurses about their ability to provide timely, high-quality care [26,31].

Therefore, the support of the management in resource allocation and utilisation is imperative to ensure the smooth flow of care in critical settings like STEMI care areas. The participants of the current study reported challenges that are related to the hospital structure like the long distance between ER and CCL as a contributing factor that delays DTB time. The participants expressed the risk of transferring the unstable STEMI cases between buildings caused delays in the ER. Due to the complexity and urgency of the patient’s condition, hemodynamic stabilisation requires greater levels of care coordination, communication, and collaboration to expedite patient transfer to CCL [32]. Even though managing hemodynamically unstable patients may unavoidably create delays, new strategies that streamline STEMI systems of care may be able to minimise the overall time to reperfusion among critically ill patients [33].

The long distance between the two departments and physical demands to quickly transfer the patient from ER to CCL and its impact on their health status were identified. In research examining the physical requirements of nurses across various activities, a notable correlation was discovered between the level of back pain experienced by nurses and the intensity of their physical exertion [34]. Reports have also indicated a connection between musculoskeletal disorders in nurses and the physical demands of their jobs. Nurses experiencing more complicated musculoskeletal pain related to their legs or feet were more likely to consider leaving their jobs [35]. Moreover, an abundance of job requirements caused nurses to experience poor health and raised their desire to leave their positions [36]. Besides the impact of long-distance walking on nurses’ health status, CCL nurse participants expressed the impact of the on-call system on their health and rest days. A study reported the impact of unpaid on-calls on the nurses’ dissatisfaction with their quality of work, moderate sleep levels, and moderate work-life balance [37].

Participants of the current study revealed challenges of people factors that contributed to the delay of DTB time. The cultural challenges were related to the nurse: patient gender impact on care within a limited time. A recent study reported that 42.6% of female patients disapproved of receiving care from the opposite gender, and 51.8% reported that they were unable to divulge some of their medical problems to the opposite-gender nurse while receiving care [38]. The study also reported that most male patients were not willing to receive care from a female nurse, and 33.6% considered receiving care from a female nurse to be contrary to their religious beliefs [38]. Patients in Islamic nations do not perceive receiving care from nurses of the opposite gender as a positive experience and are more likely to prefer nurses of the same gender [39].

Based on a study on Muslim patients, female patients were opposed to receiving care from male nurses, and most were anxious in the presence of male nurses [40]. It is therefore possible that a patient’s condition could be adversely affected, and treatment could be prolonged if they refuse to receive treatment from an opposite-gender nurse [41]. It is important to increase public awareness that in a medical emergency most Muslims recognise that saving the patient’s life is more important than finding a female or male healthcare provider, and in emergencies, it is acceptable for a male provider to treat a female patient and a female provider to treat a male patient [42]. Communicating with the STEMI patient was reported in this study as one of the people factor challenges that contributed to delayed DTB time.

Participants revealed patients’ language barrier as a communication challenge. A recent study reported that STEMI patients with language barriers had longer mean symptom-todoor time 164 minutes vs 136 minutes in a native language speaker group. Similarly, the language barrier group of patients had higher major adverse cardiovascular events (13.5% vs. 9.9%; P= 0.02) and hospitalisations within 30 days (5.1% vs. 2.0%, P= 0.001) [43]. Patient communication and reassurance were reported by the participants of this study as an essential requirement to help STEMI patients reduce distress and anxiousness. There is a significant correlation between communication and the anxiety level of pre-PCI patients. As a result of therapeutic communication, patients can clarify their condition and reduce their burden of emotions and worries [44].

In the current study, participants identified changes implemented to avoid delay in DTB time and expressed ideas and opinions that they thought may be beneficial in managing DTB time. Participants revealed the benefits of the monthly STEMI task force meetings and the feedback to the staff. A study on the emergency care pathway for STEMI explained the importance of regular meetings and feedback to improve the timeliness of care that is necessary for better outcomes [44]. The study emphasised the importance of allowing the recipients to analyse the feedback data and plan for improvement actions [44]. Hence a reporting process should be used to monitor the result of actions to assist in the continuous improvement of quality of care [44]. Research has shown that hospital-based interventions can improve STEMI diagnosis, treatment, and outcomes in resource-rich settings [45]. Nevertheless, the successful implementation of changes necessitates the attention of the hospital management system. Inadequate support from the system would adversely impact healthcare providers’ capacity to deliver high-quality care to their patients [16].

Limitations

The authors of this study encountered some limitations during the interviews. The participants’ availability when on duty preferred to participate once they were released from the clinical tasks. Some participants were uncomfortable providing data and were reassured during the interview about the anonymity and confidentiality of the data collected.

Conclusion

This qualitative study identified a broad range of nurses’ and doctors’ perceptions and opinions on the factors contributing to the delays of DTB time. The study resulted in three main themes: Barriers to Success, People Factors, and Quality Improvement. In the first theme of Barriers to Success, the participants revealed challenges in DTB time related to factors like understaffing, multiple tasks, lack of clinical pathways in the decision-making process, inefficient technological factors, unavailability of beds, hospital building structure like long walking distances between ER and CCL, and staff exhaustion. In the second theme of People Factors, the participants revealed challenges in DTB time related to the payment and the rest days, cultural challenges in gender issues and consent, and patients’ communication challenges like non-native language, stress, and anxiety before PCI. Further studies on these factors and the proposed suggestions are recommended to examine the quality of STEMI care in the future.

Acknowledgements

It is with great gratitude that I thank my supervisors Dr. Lin Zhao and Dr. Karen Livesay for their invaluable advice, continuous support, and patience throughout the manuscript preparation process. It has been an immense pleasure to learn from their vast knowledge and plentiful experience throughout my academic research.

The source of funding: None.

Ethics Approval Statement: This study was approved by the University Human Research Ethics Board (approval number 25548) as well as approved by the Research and Study Centre at the Ministry of Health, Oman.

Conflict of Interest

This research-based manuscript or a substantially similar version is not under consideration by another journal, nor has it been accepted or published elsewhere. The research was unfunded This manuscript contributes to knowledge development in nursing education. No commercial interests or financial conflicts of interest are disclosed for either of the authors. Each author contributed to the work as follows..

Author contributions:

Study design: BA, KL, ZL

Data collection: BA

Data analysis: BA, KL, ZL

Study supervision: KL, ZL

Manuscript writing: BA

Critical revisions for important intellectual content: KL, ZL

References

- Barbara Maliszewski, Madeleine Whalen, Cathleen Lindauer, Kelly Williams, Heather Gardner, et al. (2020) Quality improvement in the emergency department: a project to reduce door-to-electrocardiography times for patients presenting with chest pain. Journal of Emergency Nursing 46(4): 497-504. e2.

- Leili Yekefallah, Mahdi Pournorooz, Hassan Noori, Mahmood Alipur (2019) Evaluation of door-to-balloon time for performing primary percutaneous coronary intervention in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction patients transferred by pre-hospital emergency system in Tehran. Iranian Journal of Nursing and Midwifery Research 24(4): 281-285.

- Chih-Kuo Lee, Shih-Wei Meng, Ming-Hsien Lee, Hsiu-Chi Chen, Chia-Ling Wang, et al. (2019) The impact of door-to-electrocardiogram time on door-to-balloon time after achieving the guideline-recommended target rate. PloS one 14(9): e0222019.

- Masahiko Noguchi, Junya Ako, Takeshi Morimoto, Yosuke Homma, Takashi Shiga, et al. (2018) Modifiable factors associated with prolonged door to balloon time in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Heart and vessels 33(10): 1139-1148.

- Wen Jun Sim, An Shing Ang, Mae Chyi Tan, Wen Wei Xiang, David Foo, et al. (2017) Causes of delay in door-to-balloon time in south-east Asian patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention. PLoS One 12(9): e0185186.

- Glenn N Levine, Patrick T O'Gara, Joshua A Beckman, Sana M Al-Khatib, Kim K Birtcher, et al. (2019) Recent innovations, modifications, and evolution of ACC/AHA clinical practice guidelines: an update for our constituencies: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 139(17): e879-e886.

- David M Shavelle, Anita Y Chen, Ray V Matthews, Matthew T Roe, James A de Lemos, et al. (2014) Predictors of reperfusion delay in patients with ST elevation myocardial infarction self-transported to the hospital (from the American Heart Association's Mission: Lifeline Program). The American Journal of Cardiology 113(5): 798-802.

- Michael J Ward, Timothy J Vogus, Kemberlee Bonnet, Kelly Moser, David Schlundt, et al. (2020) Breaking down walls: a qualitative evaluation of perceived emergency department delays for patients transferred with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. BMC Emergency Medicine 20: 1-10.

- Nour Alkamel, Amr Jamal, Omar Alnobani, Mowafa Househ, Nasriah Zakaria, et al. (2020) Understanding the stakeholders’ preferences on a mobile application to reduce door to balloon time in the management of ST-elevated myocardial infarction patients–a qualitative study. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making 20: 1-10.

- Rishipathak P, S Vijayraghavan, A Hinduja (2021) Perception about the Factors Leading to Delay of Door to Balloon Time (DTBT) in Acute Myocardial Infarction Management amongst Emergency Medical Professionals in Pune, India. Journal of Pharmaceutical Research International 33(43A): 329-334.

- Long Li, Man-Yan Wu, Feng Zhang, Su-Fang Li, Yu-Xia Cui, et al. (2018) Perspective of delay in door-to-balloon time among Asian population. Journal of Geriatric Cardiology: JGC 15(12): 732.

- Tungsubutra W, D Ngoenjan (2019) Door‐to‐balloon time and factors associated with delayed door‐to‐balloon time in ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction at Thailand's largest tertiary referral centre. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice 25(3): 434-440.

- Malik MA, Rose Khan (2020) Time to Reperfusion Therapies in ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction and Identification of Factors Responsible for Delays. Age (Yr) 42: 10.2.

- Braun V, V Clarke (2013) Successful qualitative research: A practical guide for beginners.

- David Rea, Craig Froehle, Suzanne Masterson, Brian Stettler, Gregory Fermann, et al. (2021) Unequal but fair: Incorporating distributive justice in operational allocation models. Production and Operations Management 30(7): 2304-2320.

- Enns CL, JAV Sawatzky (2016) Emergency nurses’ perspectives: Factors affecting caring. Journal of Emergency Nursing 42(3): 240-245.

- Mark Jordan, Jenny Caesar (2016) Improving door-to-needle times for patients presenting with ST-elevation myocardial infarction at a rural district general hospital. BMJ Open Quality 5(1): u209049. w6736.

- BOTH I (2016) Early recognition vital in acute coronary syndrome. Practitioner 260(1797): 19-23.

- Lorelle K Martin, Virginia J Lewis, David Clark, Maria C Murphy, David Edvardsson, et al. (2020) Frontline barriers to effective paramedic and emergency nursing STEMI management: clinician perspectives. Australasian emergency care 23(2): 126-136.

- Shukri R (2020) Environmental Pressure, Nursing Shortage, Future Size, Shape and Purpose of Sultanate of Oman’s Nursing Workforce.

- Prihatiningsih D, A Hutton (2018) Electrocardiogram interpretation skills among healthcare professional and related factors: a review on myocardial infraction cases. Journal of Health Technology Assessment in Midwifery ISSN 2620: 5653.

- Tobias Augenstein, Anna Schneider, Markus Wehler, Matthias Weigl (2021) Multitasking behaviors and provider outcomes in emergency department physicians: two consecutive, observational and multi-source studies. Scandinavian Journal of Trauma, Resuscitation and Emergency Medicine 29: 1-9.

- Alkahtani M, et al. (2015) Multitasking in healthcare systems. in IIE Annual Conference. Proceedings. 2015. Institute of Industrial and Systems Engineers (IISE).

- El-Rifai O, T Garaix, X Xie (2016) Proactive on-call scheduling during a seasonal epidemic. Operations Research for Health Care 8: 53-61.

- Ilker Akbas, Abdullah Osman Kocak, Fatma Ozlem Caylak, Sultan Tuna Akgol Gur, Meryem Betos Kocak, et al. (2021) Workplace Interruptions in Emergency Department, Causes, Management and Results: A Pilot Study. Kafkas Journal of Medical Sciences 11(EK-1): 131-137.

- Kongcheep S, Manee Arpanantikul, Wanpen Pinyopasakul, Gwen Sherwood (2022) Thai Nurses' Experiences of Providing Care in Overcrowded Emergency Rooms in Tertiary Hospitals. Pacific Rim International Journal of Nursing Research 26(3).

- Mehmet Yildiz, Spencer R Wade, Timothy D Henry (2021) STEMI care 2021: Addressing the knowledge gaps. American Heart Journal Plus: Cardiology Research and Practice 11: 100044.

- Radoslav Zinoviev, Anirudh Kumar, Chetan Huded, Michael Johnson, Kathleen A Kravitz, et al. (2021) Implementation of a Comprehensive STEMI Protocol Improves Key Process Metrics for Transfer STEMI Patients. Circulation 144(Suppl_1): A14290-A14290.

- Bharath Gopinath, Akshay Kumar, Rajesh Sah, Sanjeev Bhoi, Nayer Jamshed, et al. (2022) Strengthening emergency care systems to improve patient care for ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) at a high-volume tertiary care centre in India. BMJ Open Quality 11(Suppl 1): e001764.

- Y Chandrashekhar, Thomas Alexander, Ajit Mullasari, Dharam J Kumbhani, Samir Alam, et al. (2020) Resource and infrastructure-appropriate management of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction in low-and middle-income countries. Circulation 141(24): 2004-2025.

- Confidence Alorse Atakro, Jerry Paul Ninnoni, Peter Adatara, Janet Gross, Michael Agbavor (2016) Qualitative inquiry into challenges experienced by registered general nurses in the emergency department: a study of selected hospitals in the Volta Region of Ghana. Emergency medicine international 2016(1): 6082105.

- Alice K Jacobs, Murtuza J Ali, Patricia J Best, Mark C Bieniarz, Vincent J Bufalino, et al. (2021) Systems of care for st-segment–elevation myocardial infarction: a policy statement from the american heart association. Circulation 144(20): e310-e327.

- Ahmad Alrawashdeh, Ziad Nehme, Brett Williams, Karen Smith, Angela Brennan, et al. (2021) Impact of emergency medical service delays on time to reperfusion and mortality in STEMI. Open Heart 8(1): e001654.

- Jung K, S Suh (2013) Relationships among nursing activities, the use of body mechanics, and job stress in nurses with low back pain. Journal of muscle and joint health 20(2): 141-150.

- Jison Ki, Jaegeum Ryu, Jihyun Baek, Iksoo Huh, Smi Choi-Kwon, et al. (2020) Association between health problems and turnover intention in shift work nurses: Health problem clustering. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17(12): 4532.

- Sung-Hyun Cho, Mihyun Park, Sang Hee Jeon, Hyoung Eun Chang, Hyun-Ja Hong (2014) Average hospital length of stay, nurses’ work demands, and their health and job outcomes. Journal of Nursing Scholarship 46(3): 199-206.

- W Kunaviktikul, O Wichaikhum, A Nantsupawat, R Nantsupawat, R Chontawan, et al. (2015) Nurses' extended work hours: patient, nurse and organizational outcomes. International nursing review 62(3): 386-393.

- Salar Sharifi, Sina Valiee, Bijan Nouri, Salam Vatandost (2021) Investigating patients' attitudes toward receiving care from an opposite‐gender nurse. in Nursing Forum 56(2): 322-329.

- Azizi S, S Jafari, A Ebrahimian (2019) Shortage of men nurses in the hospitals in Iran and the world: A narrative review. Scientific Journal of Nursing, Midwifery and Paramedical Faculty 5(1): 6-23.

- Walton LM, F Akram, F Hossain (2014) Health Beliefs of Muslim Women and Implications for Health Care Providers. Walton L, Akram F, Hossain F (2014) Health Beliefs of Muslim Women Living in the USA and Implications for Health Care Providers. Journal of Health Ethics, Fall.

- MR Heidari, M Anooshe, T Azadarmaki, E Mohammadi (2011) The process of patient's privacy: A grounded theory. SSU_Journals 19(5): 644-654.

- Basem Attum, Sumaiya Hafiz, Ahmad Malik, Zafar Shamoon (2018) Cultural competence in the care of Muslim patients and their families.

- Rajaratnam D, et al. (2023) Impact of Language Barriers During COVID-19 in ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction (STEMI) Presentation and Outcomes: A Single Centre Study. Heart, Lung and Circulation 32: S357-S358.

- Laura Angelici, Carmen Angioletti, Luigi Pinnarelli, Paola Colais, Egidio de Mattia, et al. (2023) EASY-NET Program: Methods and Preliminary Results of an Audit and Feedback Intervention in the Emergency Care for Acute Myocardial Infarction in the Lazio Region, Italy. in Healthcare (Basel) 11(11): 1651.

- Julian T Hertz, Kristen Stark, Francis M Sakita, Jerome J Mlangi, Godfrey L Kweka, et al. (2024) Adapting an Intervention to Improve Acute Myocardial Infarction Care in Tanzania: Co-Design of the MIMIC Intervention. Annals of Global Health 90(1): 21.