Comparative Study of Different Predictive Values of Risk Scores for Predicting Contrast Induced Nephropathy and Short Outcome after Primary Percutaneous Coronary Interventions

Moustafa Mokarrab1, AbdElhamid Ismail2, Mansour Mostafa3, AbdElaleem Elgendy4, Haitham Sabry5 and Amr Yousry6*

1Assistant Professor of Cardiology, Al-Azhar University, Egypt

2Lecturer of Cardiology, Al-Azhar University, Egypt

3Professor of Cardiology, Al-Azhar University, Egypt

4Assistant Professor of Clinical Pathology, Al-Azhar University, Egypt

5Lecturer of Internal Medicine and Nephrology, Al-Azhar University, Egypt

6Cardiology Resident, Egypt

Submission: June 15, 2017; Published: August 22, 2017

*Corresponding author: Amr Yousry, Cardiology Resident, Egypt, Email: dr.amryosry@gmail.com

How to cite this article: Moustafa M, AbdElhamid I, Mansour M, AbdElaleem E, Haitham S. Amr Y. SComparative Study of Different Predictive Values of Risk Scores for Predicting Contrast Induced Nephropathy and Short Outcome after Primary Percutaneous Coronary Interventions. J Cardiol & Cardiovasc Ther 2017; 7(1): 555703. DOI: 10.19080/JOCCT.2017.07.555703.

Abstract

Background: Meticulous risk stratification for contrast-induced nephropathy (CIN) is important for patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) and treated with primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PPCI).

Aim of the work: To compare between different risk scores for predicting contrast induced nephropathy and short outcome after primary percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with ST elevation myocardial infarction.

Material and methods: We prospectively enrolled 100 patients who presented with STEMI and treated with Primary PCI (PPCI). Mehran, Gao, Chen, ACEF or AGEF (age, serum creatinine, or glomerular filtration rate, and ejection fraction); and GRACE (Global Registry for Acute Coronary Events) risk scores were calculated for each patient. The predictive accuracy of the 6 scores for CIN, in-hospital death and major adverse clinical events (MACEs) were assessed by Receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve. CIN was defined as an absolute increase of serum creatinine by >0.5mg/dl or a relative increase of serum creatinine by ≥25% from baseline value, at 48-72 hours following the exposure to contrast media (CM). The data was analyzed using Chi-square test using SPSS (Statistical package for social science) software.

Results: All risk scores had relatively good predictive accuracy for CIN (Area under the curve (AUC) ranged from 0.671 to 0.829) and performed well for prediction of in-hospital death (AUC ranged from 0.838 to 0.973) and MACEs (AUC ranged from 0.815 to 0.926). The Mehran and Gaorisk scores had better predictive accuracy for CIN. While Mehran and Grace risk scores had better predictive accuracy for in-hospital death and MACEs.

Conclusion: Risk scores for predicting CIN perform well in stratifying the risk of CIN, in-hospital death and MACEs in patients with STEMI undergoing PPCI. The Gao, Mehran risk scores appear to have greater predictive value.

Keywords: Primary PCI; Contrast induced nephropathy; Risk scores

Introduction

Contrast-induced nephropathy (CI-N) or Contrast-induced acute kidney injury (CI-AKI) is the term given to iatrogenic renal dysfunction following intravascular (Intravenous or intra- arterial) administration of radiographic contrast media, occurring in absence of any other identifiable cause [1]. CIN is defined as either a greater than 25% increase of serum creatinine or an absolute increase in serum creatinine of 0.5mg/dl from baseline value, at 48-72 hours following the exposure to CM [2].

CIN is normally a transient process, with renal functions reverting to normal within 7-14 days of contrast administration. Less than one-third patients develop some degree of residual renal impairment [3]. CIN continues to be one of the most common major adverse side effects of cardiac catheterization, and is associated with short- and long-term morbidity and mortality [4]. This is particularly true in the population presenting with acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) which was significantly higher compared with patients undergoing non- emergent catheterization [5].

Patients undergoing primary PCI, however, are at high risk of contrast-induced nephropathy (CIN), a complication that has a serious impact on in-hospital outcome and may partially affect the overall benefit of primary PCI. Indeed, in-hospital mortality has been shown to be 20 times higher in patients who experience CIN after primary PCI as compared with those without this complication [6].

Identification and intervention for patients with STEMI with a high risk of CIN are crucial to improve clinical outcomes. Furthermore, current guide- lines recommended risk stratification before treating patients with myocardial revascularization, with an evidence level of II b [7]. Therefore, many risk scores have been established for risk assessment of CIN in patients undergoing PCI.

The Mehran risk score was the first to be developed and was derived from a cohort of 8,357 patients treated with PCI. This score, when proposed, was observed to have a c-statistic of 0.67 but excluded patients treated with PPCI and patients in shock [8]. However, the Mehran risk score was later tested for patients with STEMI who underwent PPCI and showed a strong predictive value for CIN (c-statistic: 0.80 to 0.84) [9].

Ando et al. [10] demonstrated that the ACEF risk score is useful to predict CIN in patients with STEMI, while also demonstrating that the modified ACEF (AGEF) score has a similar discriminative ability for CIN [10,11]. In addition, Raposeiras-Roubin et al. [12] reported that the GRACE score is useful for predicting CIN in patients with acute coronary syndrome with normal renal function. The GAO and Chen risk scores were established based on a cohort of Chinese patients undergoing PCI, without discrimination based on the underlying condition. They have good discriminative power for CIN in the validation data set [13,14].

Although none of those risk scores were established specifically to identify the risk of poor outcomes in patients with STEMI. Liu et al. [15] showed that the all 6 scores, in addition to prediction of CIN, had been proved to predict the in hospital outcomes.

Methods

This was a prospective observational study that was conducted from October 2016 to April 2017 and included 100 patients who presented to the emergency department of the National Heart Institute (NHI) with acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction and were treated with primary PCI. We enrolled patients presented, within 12 hours from symptoms onset mainly with typical chest pain (T.C.P) lasting for at least 30 minutes not responsive to nitrates, with ECG showed ST-segment elevation of at least 0.1mV in 2 or more contiguous leads, or development of new left bundle- branch block). Acute myocardial infarction was diagnosed in patients according to Esc guidelines 2014 [7].

Exclusion criteria were patients who not amenable for primary PCI and had recent exposure to radiographic contrast within one week before procedure. Patients on regular peritoneal or hemodialysis treatment, and who died during PCI were excluded.

The study protocol was approved by Al-Azhar University, Faculty of Medicine. A chart review was performed, and data were collected including patient demographics, medical history, examination, ECG, echocardiography and primary PCI.

History was taken included age, gender, smoking (recognized as a lifetime history of >100 cigarettes in their entire life and had continued smoking in the last 6 months was considered a positive smoking history) [16] while ex-smokers (were defined as those who had a history of smoking at least 100 cigarettes in their entire life and had completely stopped smoking for at least 6 months), current Diabetes Mellitus (was recognized as having DM if they had history of DM on admission with the use of oral anti-hyperglycemic Full agents or any extended release insulin and confirmed by laboratory HbAlc on admission if more than 6.5%) [17], dyslipidemia (was defined by total cholesterol 220mg/dl, triglyceride 150mg/dl, high-density lipoprotein (HDL cholesterol) 40mg dl or current use of anti-hyper lipdemic drug [18], hypertension (was defined as systolic/diastolic blood pressure ≥140/90mmHg or patients had a history of hypertension and current use of any antihypertensive medications) [19], Family history of premature coronary artery disease (was defined as fatal or non-fatal events in first degree men <55 or women <60 years) [20], previous PCI procedures and previous CABG, Other co-morbid conditions such as previous cerebro-vascular stroke, renal impairment and the presence of peripheral vascular disease. The onset and duration of the chest pain will be assessed precisely.

Serum creatinine was measured before the procedure and at 48 hours after the procedure. the eGFR was calculated at the time of admission and at 48hours. After the procedure, using the 4-variable Modification of Diet in Renal Disease equation (MDRD) (mL/min/1.73m2): 186 x(serum creatinine mg/dl) -1154 x (age)-0.203 x (0.742 for women)x (1.212 if black) [21]. It worth to be noted that MDRD equation had been validated extensively between the ages of 18 and 70 years old.

Serum Creatinine Kinas, Creatinine Kinas-MB, Troponin I, Complete blood count and electrolytes were measured at admission. Serum level of Lipid profiles (Low Density Lipoproteins, High Density Lipoproteins, total cholesterol and triglycerides) and basal liver functions were measured after procedure. The left ventricular EF (LVEF) was evaluated by echocardiography in all patients within 24 hours after admission.

There are many risk scores have been established for risk assessment of CIN in patients undergoing PCI. Risk scores were calculated from the initial clinical history, laboratory values, and PCI procedure. A full clinical examination included vital signs, cardiac examination to assess the Killip classification for each patient, patients were ranked by Killip class in the following way: Killip class I (included individuals with no clinical signs of heart failure), Killip class II (included individuals with rales or crackles in the lungs, an S3, and elevated jugular venous pressure), Killip class III (described individuals with frank acute pulmonary edema), and Killip class IV (described individuals in cardiogenic shock or hypotension and evidence of peripheral vasoconstriction (oliguria , cyanosis or sweating) [7]. Hypotension was defined as systolic blood pressure ≤90mmHg requiring inotropic support with medications or intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP). Heart failure included advanced congestive heart failure (New York Heart Association functional class III/IV) or acute heart failure (Killip class II-IV) [7].

All patients were given 600mg clopidogrel, 300mg aspirin, UFH/LMWH (low-dose unfractionated heparin, 50U/kg (regardless of use of glycoprotein IIb /IIIa antagonists), while the standard-dose of unfractionated heparin is 85U/kg (60U/kg with Gp IIb/IIIa antagonists) [7]. During the procedure and continued during hospital stay unless contraindicated, in addition to the conventional anti-ischemic and anti-anginal treatment as nitrates.

Hydration with intravenous normal saline solution was initiated during the procedure and maintained until 6 to 12 hours after completion of the procedure. The hydration rate was 1ml/ kg/hour or 0.5ml/kg/hour if the LVEF was <40% for patients with eGFR<60ml/min/1.73m2. Coronary angiography was performed as soon as possible, upon arrival of the on-call team. We started, by catheterization of the artery of the non-infract region, followed by the culprit one. PCI stenting of the culprit lesion(s) was done.

The primary study end point was the occurrence of CIN, defined as either a greater than 25% increase of serum creatinine or an absolute increase in serum creatinine of 0.5mg/ dl from baseline value, at 48-72 hours following the exposure to procedure [2]. The secondary end point was the occurrence of in hospital death and in hospital major adverse cardiac (MACEs) which include cardiac death, presence of reinfarction, the onset of heart failure and major bleeding.

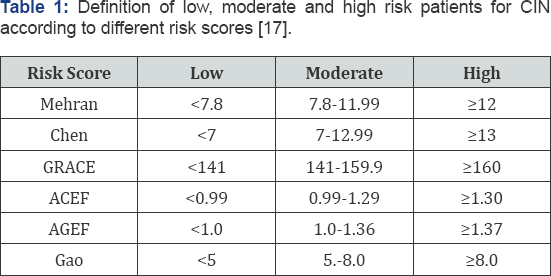

For comparison of differences among risk scores, we classified patients into risk categories according to the data presented in Liu et al. [15]. Who defined patients as low-, moderate- and high-risk for CIN [18] (Table 1 & 2).

CM: Contrast Media; EF: Ejection Fraction; EGFR: Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate; Yrs: Years; HDL; High Density Lipoproteins; MI: Myocardial Infarction

* Anemia was defined as hemoglobin (HB%)<12gm/dl16

Re-infarction was defined as the appearance of new myocardial ischemic symptoms or electrocardiographic ischemic changes accompanied by re-elevation of cardiac biomarkers (cTnI). Major bleeding was defined as the composite of intracranial or intraocular bleeding, access site hemorrhage requiring intervention, reduction in hemoglobin of 4g/dl without or 3g/dl with an overt bleeding source, reoperation for bleeding or blood product transfusion during the follow up.

Data were analyzed using Statistical Program for Social Science (SPSS) version 20.0. Quantitative data were expressed as mean ±standard deviation (SD). Qualitative data were expressed as frequency and percentage. Independent-samples t-test of significance was used when comparing between two means. Chi- square (X2) test of significance was used in order to compare proportions between two qualitative parameters. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC curve) analysis was used to find out the overall predictively of parameter in and to find out the best cut-off value with detection of sensitivity and specificity at this cut-off value.

Results

This was a prospective cross sectional observational study that involved 100 patients who presented to the emergency department of the National Heart Institute (NHI) with acute ST- elevation myocardial infarction and treated with primary PCI, within the period between October 2016 and May 2017. All patients were subjected to history taking and full clinical examination, venous samples were withdrawn, coronary angiography was recorded and intervention was done, then they were followed during hospital stay.

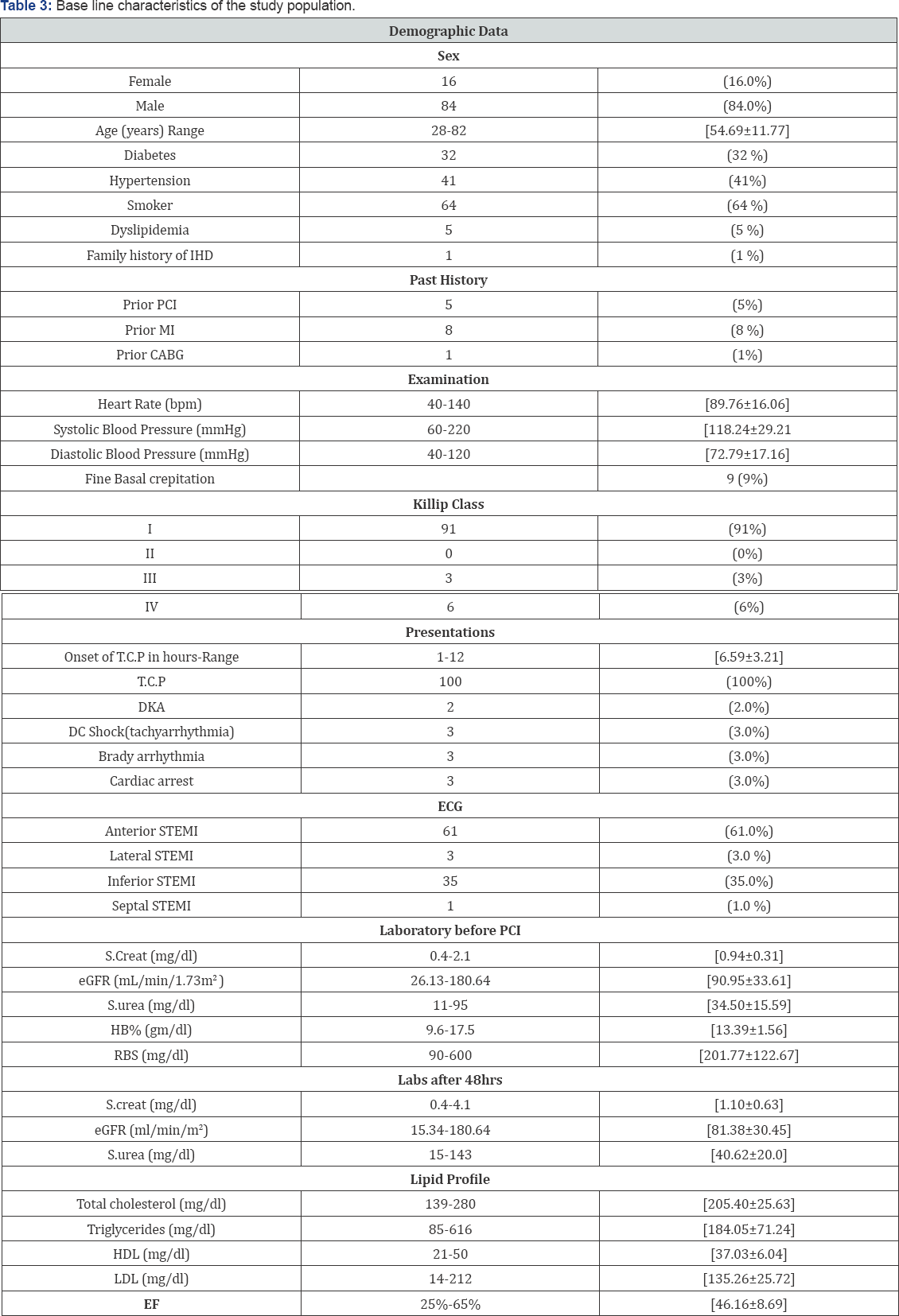

The mean age was 54.69±11.77 years (ranged from 28-82 years), the number of patients who are seventy or older was 11 (11%), while the number of patients who are below seventy was 89 (89%). Males represented 84% (84 patients) of the study population and the male to female ratio was (5.25:1). Thirty two percent of study group (32 patients) were diabetic, while 41% (41 patients) were hypertensive and 64% (64 patients) were smokers. Five percent of study group (5 patients) were dyslipidemic and one patient had family history of premature coronary artery Disease (CAD). Regarding the past history, Five percent of study group (5 patients) had history of prior PCI, 8% of patients had history of prior MI and one patient had history of CABG.

As regard clinical examination, the mean of heart rate of study group was 89.76±16.06bpm, while the mean of systolic blood pressure was118±29mmHg and the mean of diastolic blood pressure was 72±17mmHg. Concerning Killip class at presentation, 6% of patients presented with Killip class IV, while 3% of patients presented with Killip class III and 91% of patients presented with Killip class I.

All patients presented with typical chest pain, 2 % presented with Diabetic Ketoacidosis (DKA) and 3% (3 patients) presented with cardiac arrest and had successful cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) receiving D.C shock. Two patients presented with 2nd degree heart block and one patient presented with complete heart block. Majority of patients presented with anterior STEMI 61% (Table 3).

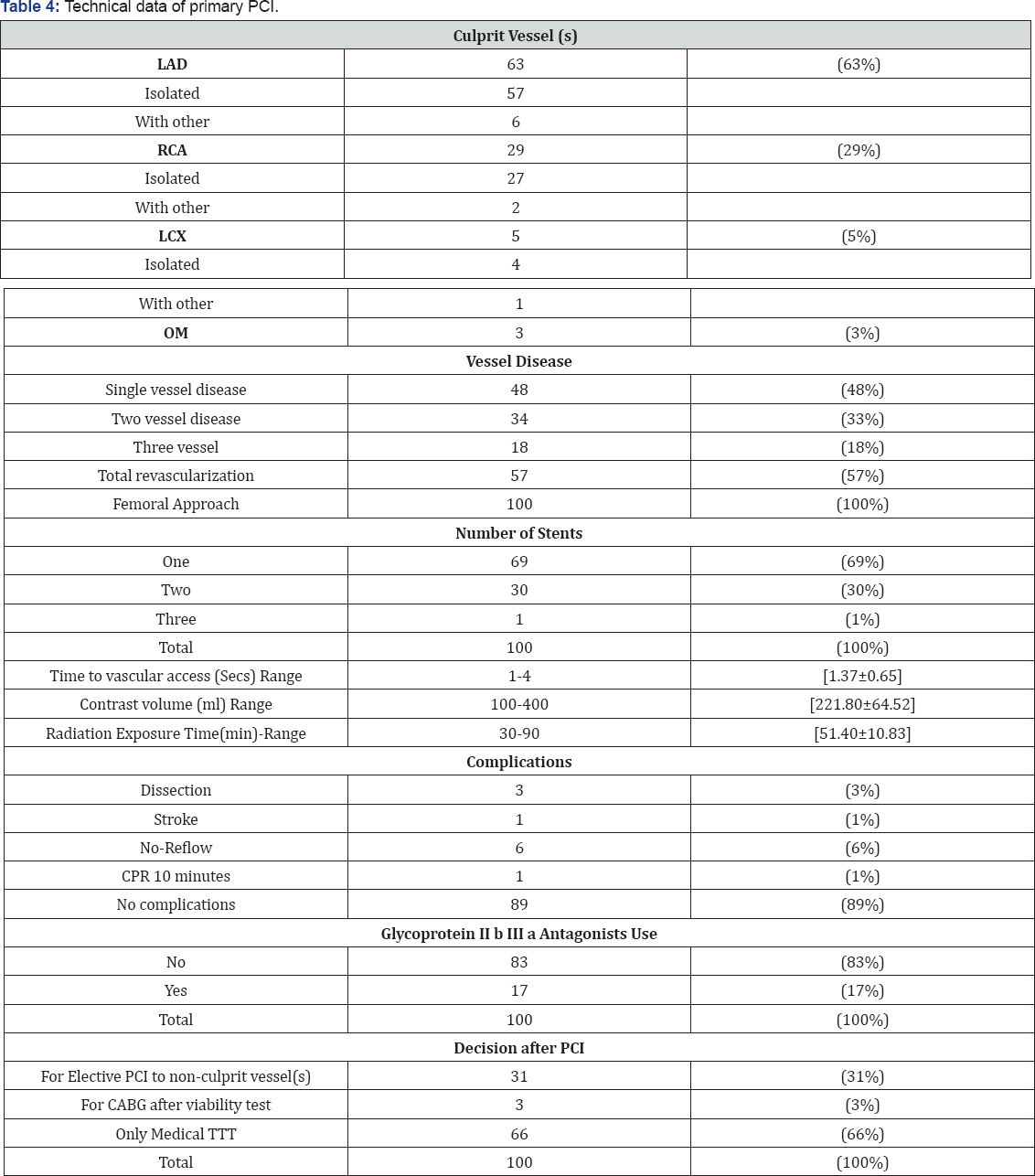

In the present study, serum creatinine level on admission was ≤1.4mg/dl in a quite high proportion of patients (92.0%) and the eGFR on admission was ≥60mL/min/1.73m2 in 80% of study population. The infarct related artery (culprit artery) was RCA in 29 patients, LAD in 63 patients and LCX in 5 patients, OM1 in 3 patients. We had 48% (48 patients) with single vessel disease, 34% (34 patients) with two vessel disease and 18% (18 patients) with multi-vessel disease (Table 4).

Regarding contrast volume used and radiation exposure time, we used 221.80±64.2ml of contrast and the mean of exposure to radiation time was 51.4±10.8 minutes. We used one stent in 69% of study group (69 patients), two stents in 30% (30 patients) and three stents only in one patient. Two interventions complicated with dissections and 6% with no-reflow. One patient had stroke and another had successful CPR in Cath lab. Glycoprotein IIb/IIa antagonists were used in 17% of study population. Twenty seven percent (27%) of study group were recommended for elective PCI for non-culprit in another session and 3% (3 patients) for CABG.

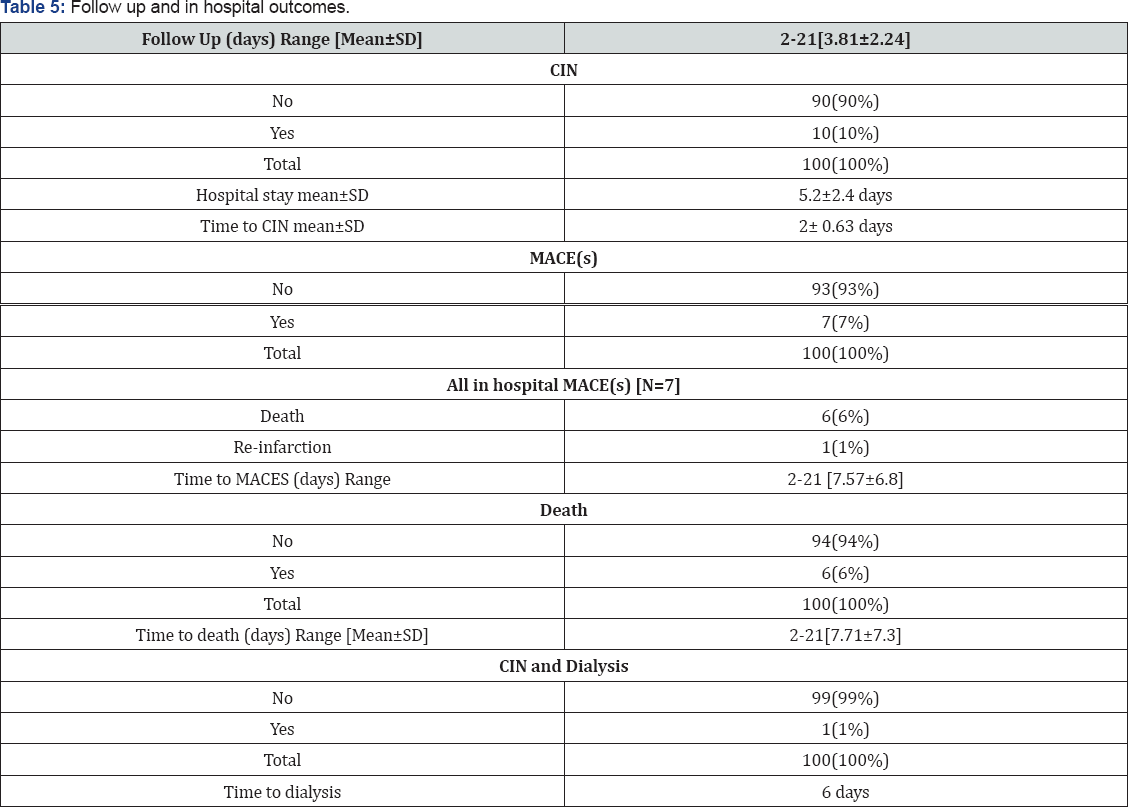

Complete follow up was achieved in 100% of patients with mean 3.81±2.24 days (range 1-21 days). The incidence of CIN in was 10%, the patients with CIN had poor in-hospital outcome. Their hospital stay was significantly prolonged with a mean 5.2±2.4 days. The incidence of in hospital MACEs was 7% and 6% for in hospital death. Only single patient underwent dialysis (Table 5).

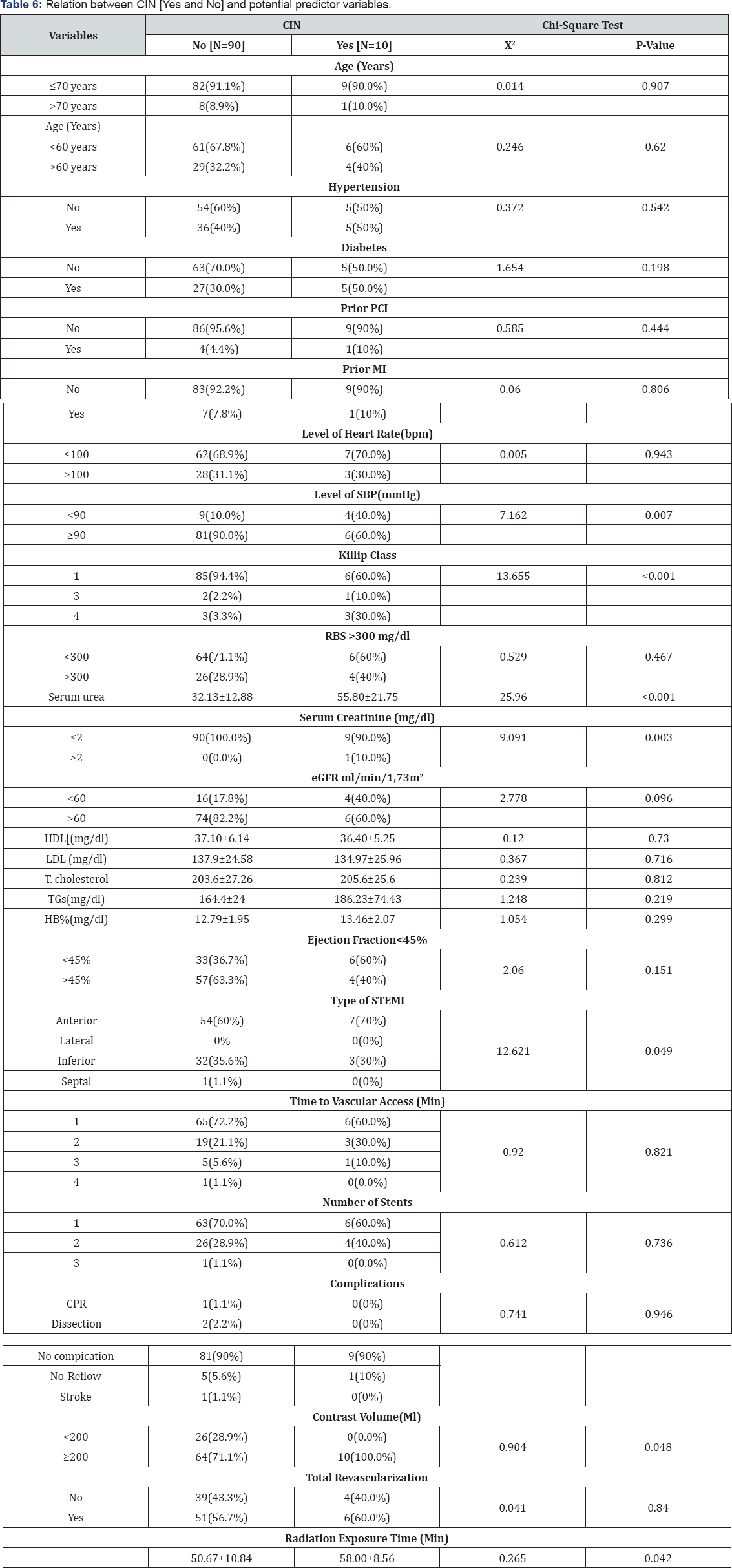

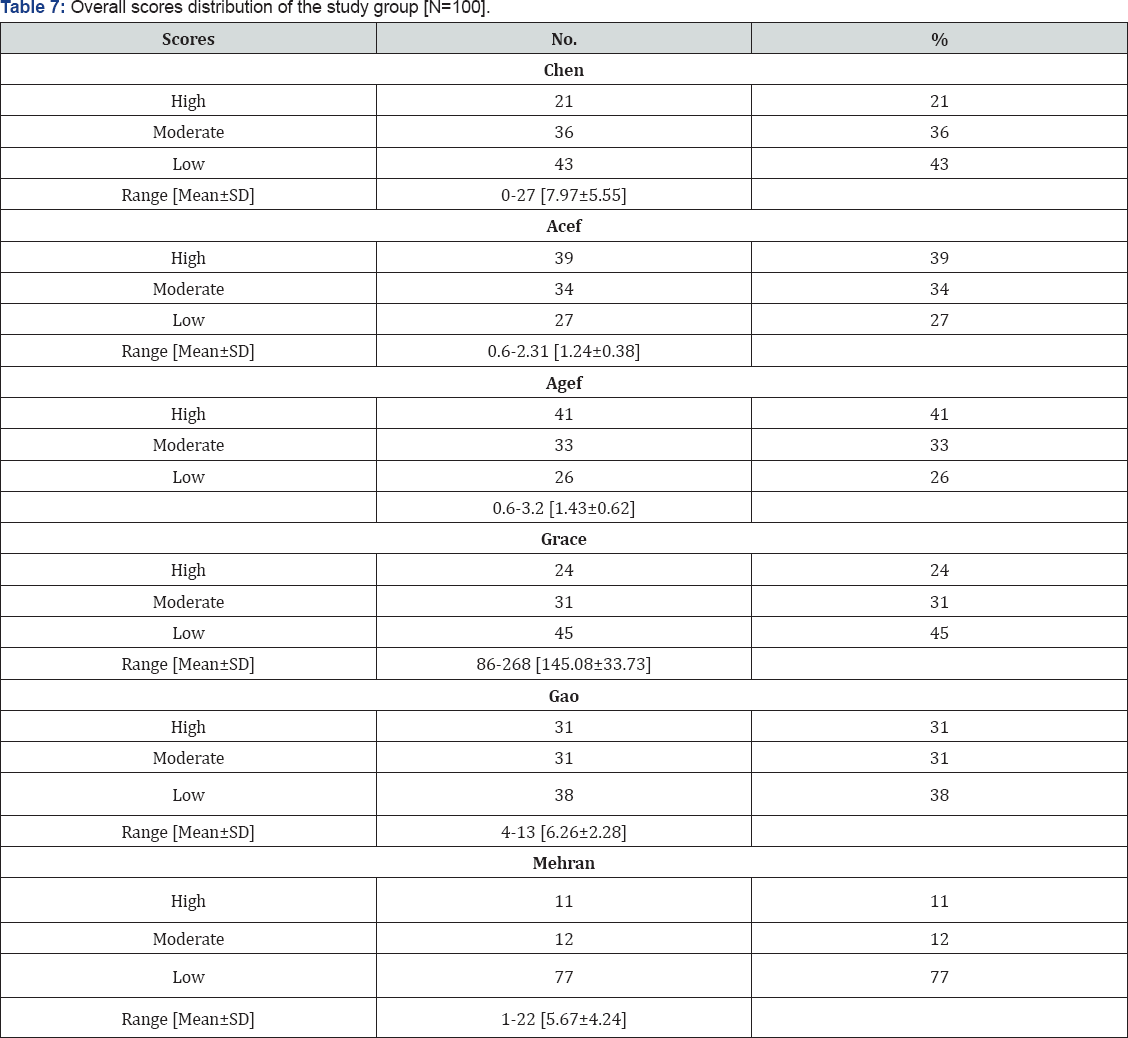

For CIN, there was statistical significant relation between CIN according to serum creatinine ≥2mg/dl at admission (p value =0.003), with serum urea (p value <0.001), systolic blood pressure <90mmHg at admission (p value =0.007), with Killip class at admission (p value <0.001), with anterior STEMI (p value =0.049), with contrast volume used ≥200ml (p value=0.048) and radiation exposure time (p value=0.042).

On the other hand, there was no significant relation with Age ≥70 years, presence of diabetes, history of hypertension, prior MI, prior PCI, EF <45%, RBS >300mg/dl, eGFR <60ml/min/1.73m2, lipid profile (LDL, HDL, total cholesterol and triglycerides), time to vascular access, heart rate on admission, number of stents used and total revascularization Table 6 & 7 and Figure 1.

p-value <0.05 S; p-value <0.001 HS; p-value >0.05 NS

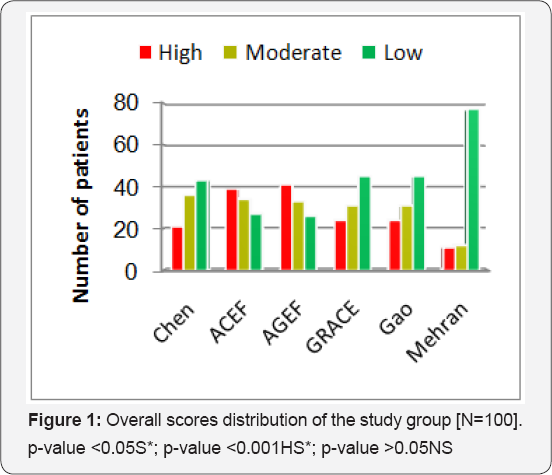

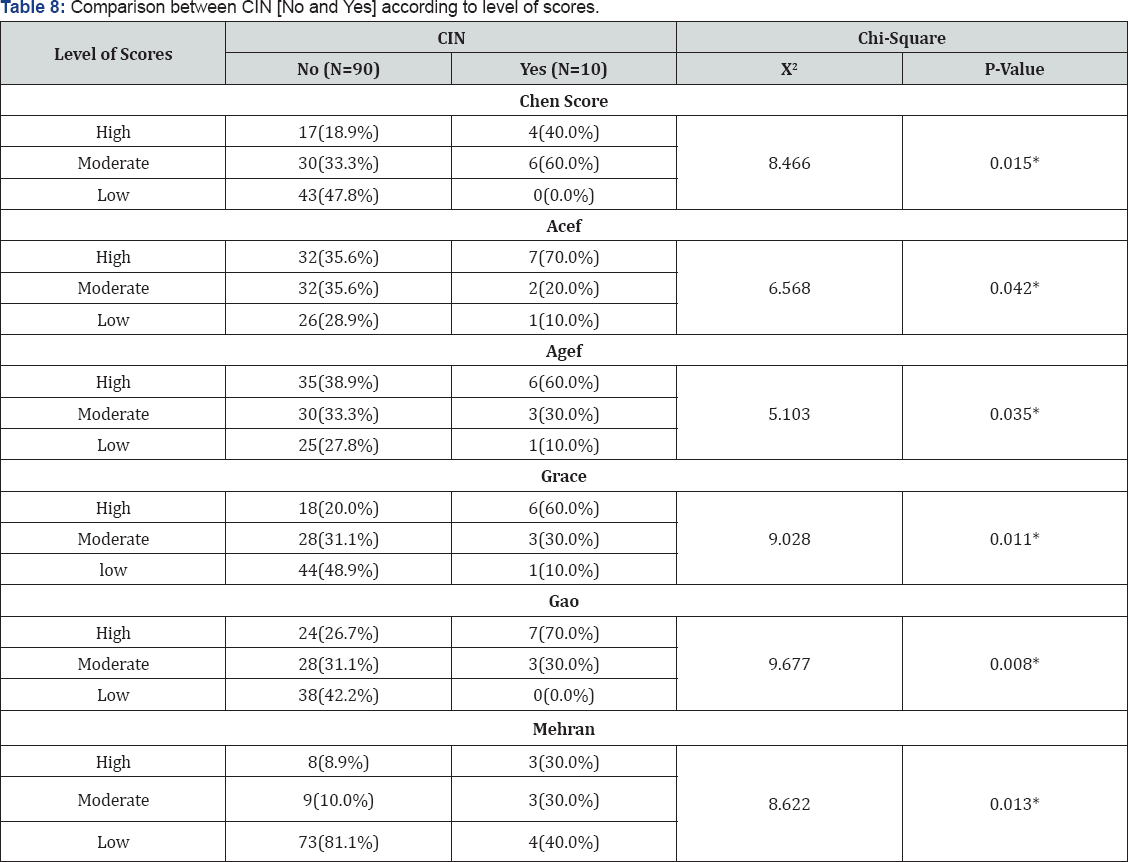

Our study demonstrated that there was statistically significant difference between CIN [No or Yes] according to level of all 6 risk scores (Table 8 and Figure 2).

p-value&3x003C;0.05 S*; p-value <0.001 HS*; p-value >0.05 NS.

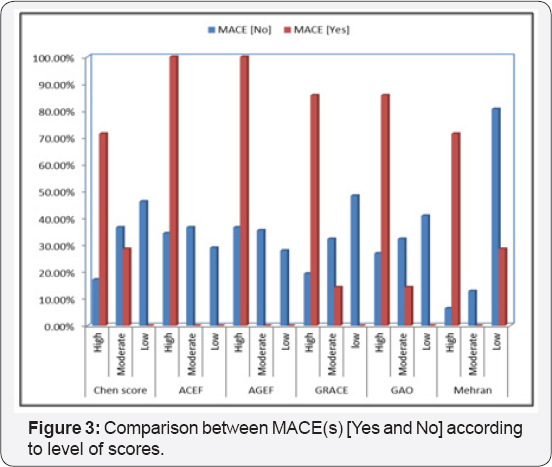

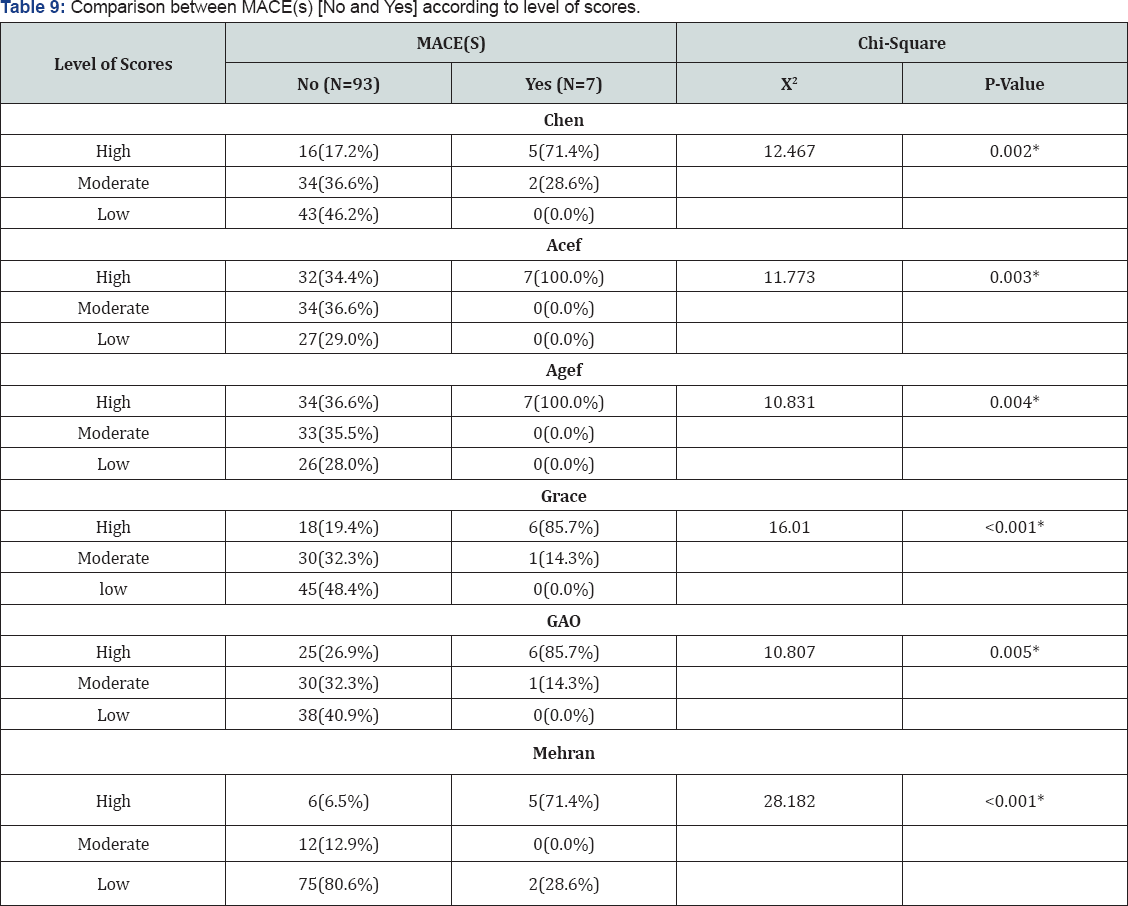

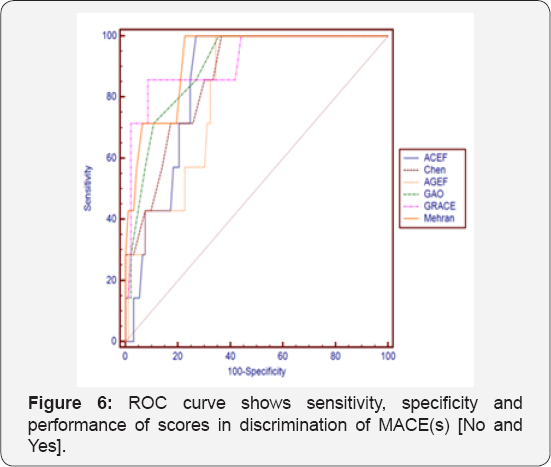

In this study, There was statistically significant difference between MACE(s) [No or Yes] according to level of all risk scores (Table 9 & 10 and Figure 3 & 4).

p-value<0.05 S*; p-value π.001 HS*; p-value >0.05 NS.

p-value <0.05 S*; p-value <0.001 HS*; p-value >0.05 NS.

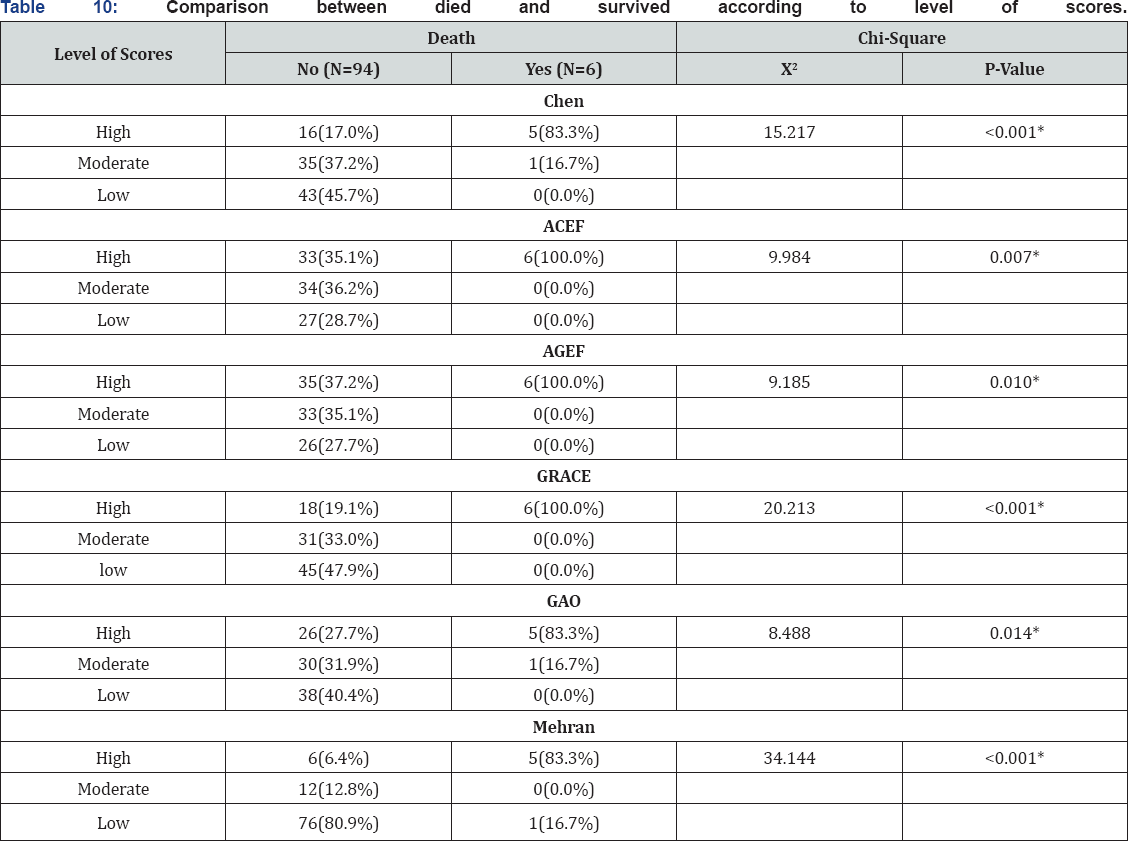

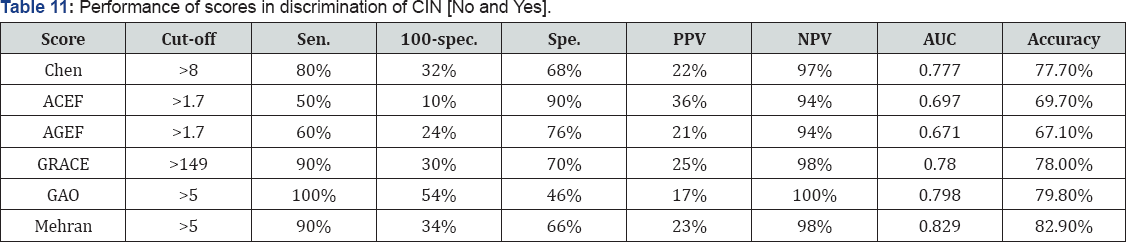

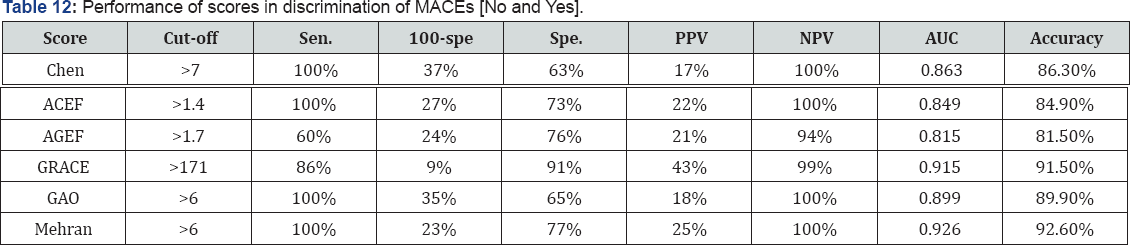

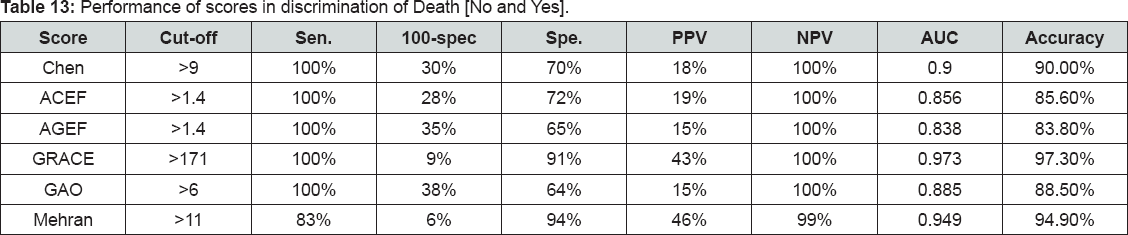

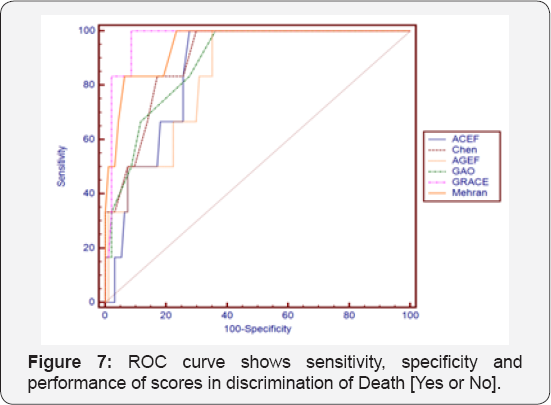

There was statistically significant difference between death [No or Yes] according to level of all risk scores. All risk scores showed relatively good predictive accuracy for CIN (ranged from 82.9%-67.1%). Mehran score has the highest predictive accuracy for CIN (82.9%) with 100% sensitivity and 46% specificity. All 6 risk scores showed high predictive accuracy for in hospital MACEs (ranged from 92.6 to 81.5%). Mehran risk score showed highest predictive accuracy in hospital with 100% sensitivity and 77% specificity. All 6 risk scores showed high predictive accuracy for in hospital death (ranged from 97.3% to 83%). GRACE risk score showed the highest predictive accuracy for in hospital death with 100% sensitivity and 91% specificity (Table 11-13 and Figure 5-7).

AUC: Area under the Curve; Spe: Specificity; Sens: Sensitivity; PPV: Positive Predictive Value; NPV: Negative Predictive Value

AUC: Area Under the Curve; Spe: Specificity; Sens: Sensitivity; PPV: Positive Predictive Value; NPV: Negative Predictive Value

AUC: Area Under the Curve; Spe: Specificity; Sens: Sensitivity; PPV: Positive Predictive Value; NPV: Negative Predictive Value

Discussion

This was a prospective observational study conducted in the National Heart Institute (NHI) and involved 100 patients who presented with acute ST- elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) that was treated using primary PCI. The present study was aimed to compare between different risk scores for predicting contrast induced nephropathy and short outcome after Primary percutaneous Coronary Intervention in patients with ST elevation myocardial Infarction. In addition to prediction of CIN, we demonstrated that those different risk scores performed well for predicting in hospital MACEs and death.

The observed incidence of CIN after primary percutaneous coronary intervention differs greatly among various studies, largely because of varying definitions and associated variable risk factors. Not surprisingly, the frequency of CIN in our study was about 10%, which is lower than the results observed by Marenzi et al. [4] who studied 208 consecutive patients admitted to coronary care unit (CCU) for ST-segment elevation AMI who were treated with primary PCI. CIN was observed in approximately 19% of STEMI patients who underwent primary PCI. Our data may be related to the close collaboration with the local nephrologist in our institution may have reduced the risk of CIN development as the result of a prompt activation of the hydration protocol.

However, Raposeiras-Roubin et al. [12] studied 202 consecutive patients presented with AMI (STEMI and NSTEMI) and with normal kidney function (eGFR >60/mL/min/1.7m2) undergoing coronary angiography and follow up during hospital stay. The incidence of CIN was 6% which was lower than our study, as we did not exclude patients presented with renal dysfunction from the study as 20% of our study population presented with renal dysfunction (eGFR <60ml /min/1.73m2).

In this study only 1% of patients who had CIN underwent dialysis and this was concordant with McCullough et al. [20] who demonstrated that the occurrence of acute renal failure requiring dialysis after coronary intervention is rare (1%). This study showed that, in STEMI patients undergoing primary PCI, CIN was a significant and independent predictor of poor in-hospital outcome. This was concordant with Liu et al. [15], who may be the first to compare between those 6 risk models for CIN in patients with STEMI, prospectively enrolled 422 consecutive patients with STEMI undergoing PPCI and showed that CIN was a highly significant predictor for in hospital mortality (p value =0.001).

In This study, the incidence of in-hospital death was 6% of study population while Liu et al. [15] who showed that the incidence of in hospital death was 4%. Our data may due to late presentation of study population. MACEs occurred in 7% of our study population while Liu et al. [15], showed that the incidence of MACEs was 17% of study population. This was due they enrolled major adverse cardiac and non-cardiac events in their study.

Univariate Analysis between different potential predictor variables and in hospital outcomes:

CIN: Our study concluded that there was statistically significant relation between CIN and following predictor variables:

a) Serum creatinine ≥2mg/dl at admission (p value = 0. 003), which was concordant with Ando et al. [10] who studied 481 patients with STEMI underwent primary PCI including patients with cardiogenic shock and demonstrated that baseline Serum creatinine ≥1.5mg/dl was highly significant predictor for CIN (p value = <0.001).

b) Systolic blood pressure <90mmHg at admission (p value =0.007), which was concordant with Chen et al. [13], who retrospectively studied 1500 Consecutive Asian patients who underwent PCI for ACS (training data based group) and demonstrated that the hypotension at admission was a highly significant predictor for CIN (p value=<0.001).

c) Killip class at admission (p value =<0.001), which was concordant with Raposeiras-Roubin et al. [12], who showed that Killip class >I at admission was highly significant predictor for CIN (p value= 0.001).

d) Contrast volume used ≥200ml (p value=0.048), which was consistent with Gao et al. [14], who retrospectively studied 3945 Asian patients undergoing coronary angiography or percutaneous coronary intervention and demonstrated that the contrast volume used >200mL was associated with a significantly higher risk of CIN and the CIN risk would be increased with the increment of contrast volume.

e) With anterior STEMI (p value=0.049), this was concordant with Marenzi et al. [4], who found a that patients presented with anterior STEMI were at a higher risk for CIN (p value=0.0015).

f) In-hospital stay (p value 0.03), this was consistent with study Ando et al. [11], who found that patients with CIN had a significant prolonged In-hospital stay (p value =<0.001).

On the other hand, we found that there was no statistically significant relation of the following factors and CIN:

A. With Age ≥70 years (p value =0.907), which was in disagreement with Chen et al. [13], who found that the age of >70 years was an independent predictor of CIN because a number of structural and functional degenerative changes in kidneys could make old persons prone to CIN our data may due to we had only 11% of our study population with age of seventy or older. However, Raposeiras-Roubin et al. [12], found that Age ≥75 years was not a significant risk factor for CIN (p value= 0.365).

B. With diabetes (p value= 0.198), this was discordant with Chen et al. [13], who found that diabetes was a predictor of CIN (p value = <0.001), but In 2006, the CIN Consensus Working Panel stated: "it is not clear whether the risk of CIN is significantly increased in patients with diabetes who do not have renal impairment") and the updated contrast Media Safety Committee (CMSC) of European Society of Urogenital Radiology guidelines published in 2011 also hold the same opinion [2].

C. With eGFR <60 ml/min/1.73m2 at admission (p value = 0.096), which was inconsistent with Gao et al. [14] who found that the baseline renal function was one of the strongest predictors for CIN development. This may due to the renal function in a quite high proportion of our patients (80.0%) was normal (i.e., eGFR >60 mL/min/1.73m2). Because the compensatory capacity of kidney diminished in the patients with renal insufficiency, it is easier to develop acute kidney injury affected by nephrotoxic agents, including contrast media.

D. With Heart rate >100bpm at admission (p value= 0.943), which was consistent with Ando et al. [10], who found that heart rate at admission was not a predictor of CIN (p value= 0.06).

E. With depressed EF <45% (p value= 0.151), which was concordant with Raposeiras-Roubin et al. [12], who demonstrated that depressed EF was not a predictor of CIN (p value =0.541).

F. With history of HTN (p value=0.542), which was consistent with Gao et al. [14], who demonstrated that history of hypertension was significant predictor of CIN (p value=0.001).

G. With patients had multi vessel disease and this was discordant with Gao et al. [14], who found that patients with multi vessel disease were at high risk for CIN (p value= 0.002).

H. Prior PCI and Prior CABG and this was concordant with Gao et al. [14], who found that patients with past history of CABG or PCI were not at risk for CIN (p value=0.529).

I. With number of stents used (p value =0.736).

J. With patients underwent total revascularization (p value=0.840).

Death and MACEs

Our study concluded there was significant relation between in hospital outcomes and the following predictor variables:

I. With CIN which was an independent predictor for in hospital death. This was concordant with Ando et al. [10] who found that CIN was a significant risk predictor for in hospital mortality as 66% of deaths had CIN.

II. With heart rate ≥100bpm on admission (p value=0.004), SBP <90mmHg on admission (p value=<0.001) and Killip class on admission (p value= <0.001). This consistent with previous study [12,22].

On the other hand, our study showed that there was no significant relation between in hospital death and the following; with Age ≥70 years (this was inconsistent with Valente et al. [23] who demonstrated that age ≥75 years was a predictor of death in patients presented with STEMI complicated with cardiogenic shock treated with PPCI with p value=0.002), presence of diabetes, history of hypertension (this was discordant with Valente et al. [23], who demonstrated that history of HTN was a predictor of death with p value =0.003), prior MI, Prior PCI, serum creatinine >2mg/dl at admission(this was discordant with Valente et al. [23], who demonstrated that serum creatinine >1.5mg/dl at admission was a predictor of death with p value =0.003), RBS >300mg/dl at admission (this was discordant with Valente et al. [23] who demonstrated that RBS >200mg/dl was a predictor of death with p value =0.002), eGFR <60ml/min/1.73m2 on admission, HDL level, time to vascular access, number of stents used, total revascularization and with complications of PCI.

Comparison between different risk scores predicting in hospital outcomes

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC curve) analysis was used to find out the overall predictivity of parameter in and to find out the best cut-off value with detection of sensitivity and specificity at this cut-off value.

CIN: This study demonstrated that all risk scores showed relatively good predictive accuracy for CIN (ranged from 82.9%- 67.1%), which was concordant with Liu et al. [16], who showed that the predictive accuracy of all scores for CIN were ranged from 87.6%-74.6%. Our study showed that Mehran score had the highest predictive accuracy for CIN (82.9%), with 90% sensitivity and 66% specificity. while The ACEF and AGEF score showed the lowest predictive accuracy for CIN (69.7%, 67.1% respectively). On the other hand, Liu et al. [16], demonstrated that Gao, ACEF and AGEF scores had the highest predictive accuracy for CIN- narrow (87.6%, 87.3% and 87.1% respectively). While Chen score had the lowest predictive value for CIN (74.6%).

In hospital MACEs: Our Study demonstrated that the All 6 risk scores showed high predictive accuracy for in hospital MACEs (ranged from 92.6 to 81.5%), which was higher than the results published by Liu et al. [16], in which predictive accuracy for MACEs was ranged from 76.3% to 68.5 %.

This study showed that Mehran risk score showed the highest predictive accuracy for MACEs with 100% sensitivity and 77% specificity. While the ACEF and AGEF score showed the lower predictive accuracy for MACEs (84.9%, 81.5% respectively). On the other hand, Liu et al. [16], showed that the ACEF and AGEF scores had the highest predictive accuracy for MACEs (76.3%, 75.8% respectively) and Mehran showed the lowest predictive accuracy for MACEs 68.5%.

In hospital death: This study demonstrated that All 6 risk scores showed high predictive accuracy for in hospital death (ranged from 97.3% to 83%), which was concordant with Liu et al.[16], who showed that the predictive accuracy of all 6 scores for in hospital death was ranged from 93.6 % to 78.4% [16].

This study showed that GRACE risk score had the highest predictive accuracy for in hospital death with 100% sensitivity and 91% specificity. While the ACEF and AGEF score had the lowest predictive accuracy (85.6%, 83.8% respectively for MACEs). On the other hand, Liu et al. [16], demonstrated that ACEF and AGEF had the highest predictive accuracy for in hospital death (92.5%, 93.6 % respectively), while Chen score had the lowest predictive accuracy 78.4%.

Conclusion

Risk scores for predicting CIN perform well in stratifying the risk of CIN and in-hospital death or MACEs in patients with STEMI undergoing PPCI. In this study, the Mehran [8] and Gao [14] scores was observed to had the higher predictive accuracy for CIN and in hospital MACEs than the other risk scores, all of which are exclusive of procedural factors. The GRACE risk score is a more comprehensive score, and displayed the highest predictive accuracy for in hospital death.

Recommendations

This study recommends risk stratification for CIN before treating patients with myocardial revascular- ization using different risk scores especially Mehran [8] and Gao [14] risk scores as identification and intervention for patients with STEMI with a high risk of CIN are crucial to improve clinical outcomes. This study recommends starting hydration before and after PCI, as well as an optimized choice of contrast medium, for the prevention of CIN. On the other hand, renal function should always be monitored in patients with AMI after catheterization, even in patients with GFR >60mL/min/1.73m. The observed different predictive values were exclusive to patients with STEMI, and we recommend to do a research for other patients who undergoing elective PCI.

This study had several potential limitations. First, the study was performed at a single center with a relatively small study population; thus, results should be interpreted with caution. Second, the different predictive values observed were exclusive to patients with STEMI, and caution should be taken in generalizing the findings for other patient populations. Third, we did not include all risk scores developed for CIN because we believe that those risk scores not included are excessively complicated or have been proved in other patient populations.

References

- Kapoor, Gaur (2017) Contrast-induced Nephropathy. Coronary Angioplasty. Evolved to Perfection.

- Stacul F, van der Molen AJ, Reimer P, Webb JA, Thomsen HS, et al. (2011) Contrast induced nephropathy: updated ESUR contrast media safety committee guidelines. Eur Radiol 21(12): 2527-2541.

- Abe M, Morimoto T, Akao M, Furukawa Y, Nakagawa Y, et al. (2014) Relation of contrast-induced nephropathy to long-term mortality after percutaneous coronary intervention. Am J Cardiol 114(3): 362-368.

- Marenzi G, Lauri G, Assanelli E, Campodonico J, De Metrio M, et al. (2004) Contrast-induced nephropathy in patients undergoing primary angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 44(9): 1780-1785.

- Chong E, Poh KK, Liang S, Soon CY, Tan HC (2010) Comparison of risks and clinical predictors of contrast-induced nephropathy in patients undergoing emergency versus nonemergency percutaneous coronary interventions. J Interv Cardiol 23(5): 451-459.

- Marenzi G, Assanelli E, Campodonico J, Lauri G, Marana I, et al. (2009) Contrast volume during primary percutaneous coronary intervention and subsequent contrast-induced nephropathy and mortality. Ann Intern Med 150(3): 170-177.

- Windecker S, Kolh P, Alfonso F, Collet JP, Cremer J, et al. (2014) 2014 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS)Developed with the special contribution of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI). Eur Heart J 35(37): 2541-2619.

- Mehran R, Aymong ED, Nikolsky E, Lasic Z, Iakovou I, et al. (2004) A simple risk score for prediction of contrast-induced nephropathy after percutaneous coronary intervention. Development and initial validation. J Am Coll Cardiol 44(7): 1393-1399.

- Sgura FA, Bertelli L, Monopoli D, Leuzzi C, Guerri E, et al. (2010) Mehran contrast-induced nephropathy risk score predicts short-and long-term clinical outcomes in patients with st-elevation-myocardial infarction. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 3(5): 491-498.

- Andò G, Morabito G, de Gregorio C, Trio O, Saporito F, et al. (2013) The ACEF score as predictor of acute kidney injury in patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Int J Cardiol 168(4): 4386-4387.

- Andò G, Morabito G, de Gregorio C, Trio O, Saporito F, et al. (2013) Age, glomerular filtration rate, ejection fraction, and the AGEF score predict contrast-induced nephropathy in patients with acute myocardial infarction undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 82(6): 878-885.

- Raposeiras-Roubin S, Aguiar-Souto P, Barreiro-Pardal C, López Otero D, Elices Teja J, et al. (2013) GRACE risk score predicts contrast-induced nephropathy in patients with acute coronary syndrome and normal renal function. Angiology 64(1): 31-39.

- Chen YL, Fu NK, Xu J, Yang SC, Li S, et al. (2014) A simple preprocedural score for risk of contrast-induced acute kidney injury after percutaneous coronary intervention. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 83(1): E8-E16.

- Gao YM, Li D, Cheng H, Chen YP (2014) Derivation and validation of a risk score for contrast-induced nephropathy after cardiac catheterization in Chinese patients. Clin Exp Nephrol 18(6): 892-898.

- Liu YH, Liu Y, Zhou YL, He PC, Yu DQ, et al. (2016) Comparison of different risk scores for predicting contrast induced nephronpathy and outcomes after primary percutaneous coronary intervenetion in patients with ST elevation myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 117(12): 1896-1903.

- Levey AS, Bosch JP, Lewis JB, Greene T, Rogers N, et al. (1999) A more accurate method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine. a new prediction equation. Ann Intern Med 130(6): 461470.

- Leung Y, Kaplan GG, Rioux KP, Hubbard J, Kamhawi S, et al. (2012) Assessment of variables associated with smoking cessation in Crohn's disease. Dig Dis Sci 57(4): 1026-1032.

- Kilpatrick ES, Bloomgarden ZT, Zimmet PZ (2009) International Expert Committee Report on the Role of the A1C Assay in the Diagnosis of Diabetes Response to the International Expert Committee. Diabetes care 32(12): e159.

- Mancia G, Fagard R, Narkiewicz K, Redon J, Zanchetti A, et al. (2013) 2013 ESH/ESC guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 34(28): 2159-2219.

- Catapano AL, Graham I, De Backer G, Wiklund O, Chapman MJ, et al. (2016) ESC/EAS Guidelines for the Management of Dyslipidaemias. Eur Heart J 37(39): 2999-3058.

- McCullough PA, Adam A, Becker CR, Davidson C, Lameire N, et al. (2006) Epidemiology and prognostic implications of contrast-induced nephropathy. Am J Cardiol 98(6): 5K-13K.

- Abdel-Kader K, Unruh ML, Weisbord SD (2009) Symptom burden, depression, and quality of life in chronic and end-stage kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 4(6): 1057-1064.

- Valente S, Lazzeri C, Vecchio S, Giglioli C, Margheri M, et al. (2007) Predictors of in-hospital mortality after percutaneous coronary intervention for cardiogenic shock. Int J Cardiol 114(2): 176-182.