Conventional Median Sternotomy vs. Upper Partial Sternotomy in Mitral Valve Replacement

Mohamed Zayed¹, Al Husseiny Gamil², Nashaat Abdel Hameed¹, Saleh Raslan² and Hossam Walley¹*

¹Cardiac Surgery Department, National Heart Institute (NHI), Egypt

²Cardiothoracic Surgery Faculty of Medicine, AL-Azhar University, Egypt

Submission: February 20, 2017; Published: April 03, 2017

*Corresponding author: Hossam Walley, Cardiac Surgery Department, National Heart Institute (NHI), India, Email:hossamwally@gmail.com

How to cite this article: Mohamed Z, Nashaat A H, Hossam W, A Husseiny G, Saleh R. Conventional Median Sternotomy vs. Upper Partial Sternotomy in Mitral Valve Replacement. J Cardiol & Cardiovasc Ther 2017; 4(2): 555632. DOI:10.19080/JOCCT.2017.04.555632

Abstract

Background: Full median sternotomy has been a standard surgical approach for heart surgery for more than 50 years. Several advantages increasing the use of less invasive approaches to the mitral valve surgery including, cosmetic, blood product use, respiratory, and pain advantages over conventional surgery. Parasternal incision, right mini-thoracotomy and partial sternotomy are described approaches for less invasive cardiac surgery.

Objective: Comparing the standard approach via conventional median sternotomy vs. less invasive approach via upper partial sternotomy.

Methods: Sixty patients, underwent mitral valve replacement with or without tricuspid valve repair in NHI, were enrolled in this study and divided into two equal groups, Group I via conventional median sternotomy (CMS), and Group II via upper partial sternotomy (UPS). The preoperative characteristics, operative variables, mortality, and morbidity were analyzed prospectively.

Results:. No difference was found between the two groups as regards the mortality. However, in Group I, blood loss was significantly higher, while in Group II cross clamp time and total bypass time were significantly higher. Minimal invasive group showed less time on mechanical ventilation, ICU stay and total hospital stay. In Group I, two patients (7%) developed deep sternal wound infection, and one patient (3%) suffered unstable sternum. In Group II, one patient (3%) required conversion to full sternotomy, and one patient (3%) required permanent pacemaker.

Conclusion: Upper partial sternotomy considered a safe alternative for mitral valve replacement; it provides adequate exposure for valve. Conventional cardiopulmonary bypass and cardioplegia solution administration can be used, as no specific instruments or endoscope were need, and superior on conventional technique as provided better patient satisfaction for pain and cosmetic outcome.

Keywords: Cardiac surgery; Mitral valve replacement; Tricuspid valve repair; Partial sternotomy; Median sternotomy

Introduction

In the mid-1990s, minimally invasive approaches for mitral valve operations were pioneered with the intent of reducing morbidity, postoperative pain, and blood loss; improving cosmesis; shortening hospital stay; and reducing cost compared with the 50-year-old conventional median sternotomy approach. Furthermore, it was believed that less spreading of the incision, no interference with the diaphragm, and less tissue dissection might improve outcomes, particularly respiratory function [1,2].

Indeed, a less invasive approach to cardiac surgery has been widely adopted in clinical practice [3,4]. Compared to conventional full median sternotomy, less invasive approaches reduce incision size and surgical trauma. It has been reported to reduce morbidity, accelerate recovery, and shorten hospital [3,5], with equally durable late outcome [6]. Several incisions for minimally invasive cardiac surgery has been described: parasternal incision [7,8] right mini-thoracotomy [9-11] & partial sternotomy [12-14].

Patients and Methods

from August 1, 2015 till the end of September 30, 2016, Sixty patients were prospectively enrolled in our study and randomly assigned into two equal groups, group I conventional median sternotomy (CMS group, n=30) or group II upper partial sternotomy (UPS group, n=30). All patients were operated bythe same surgeon. The study was done in the national heart institute (NHI).

Operative techniques

Group I CMS incision was 25 to 30cm long. It began 1 to 2cm below the sternal notch and extending downwards to the xiphoid process. The full sternotomy was performed from sternal notch and extended downwards to the xiphoid process. Cannulation: Central arterial cannulation of the ascending aorta and venous cannulation of superior and inferior vena cavae. Mitral valve exposure through stander paraseptal left atriotomy. Tricuspid valve exposure through right atriotomy, and tricuspid repair was done by de-vaga on beating heart if needed.

Group II UPS incision was 8 to 10cm long. It began half way between the sternal notch and the angle of Louis, and ended above the fourth intercostal space. The upper partial sternotomy was performed from sternal notch and extended to the left fourth intercostal space, forming a reverse j-shape sternotomy. Care was taken not to injure the left internal thoracic artery. Cannulation: central arterial cannulation of the ascending aorta and superior vena cava before establishing thebypass and inferior vena cava was cannulated after initiation of the bypass on an empty heart. Mitral valve exposure through transseptal approach. Tricuspid valve exposure through same right atriotomy incision for the transseptal approach and tricuspid repair were done same as group I.

Anesthetic techniques, cardiopulmonary bypass and myocardial protection

Conventional general anesthesia, standard cardio pulmonary bypass, and myocardial protection using intermittent perfusion of ante grade warm blood cardioplegia into the aortic root were conducted in both groups.

Statistical analysis

All data were collected on standardized forms, entered in a computerized database, and analyzed with statistical software. Results were statistically represented in terms of range, mean, standard deviation and percentages. Continuous data of different groups were compared with paired t-tests and categorical data (parametric data) by Pearson’s chisquare x2 test was performed. A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

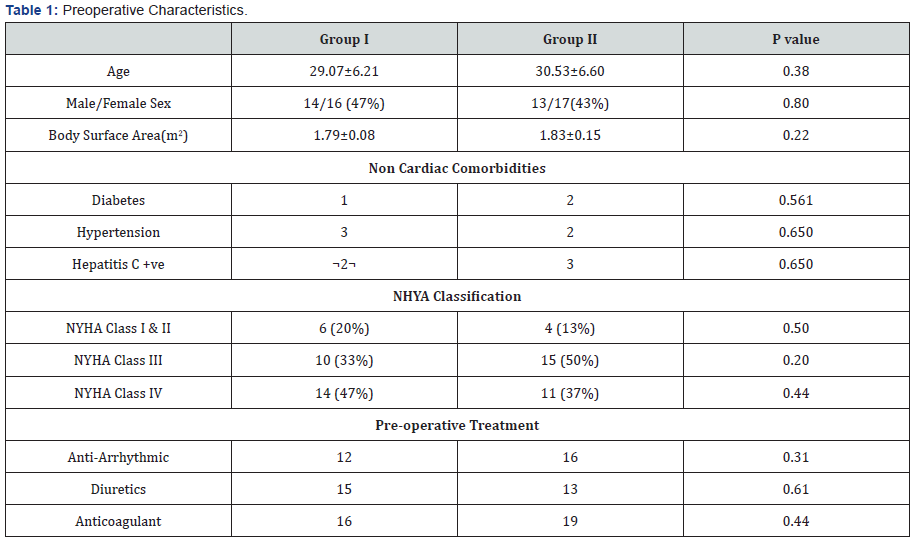

There were no statistically significant differences between Group I and Group II as regards to the preoperative characteristics. Patient’s preoperative Characteristics were shown in Table 1.

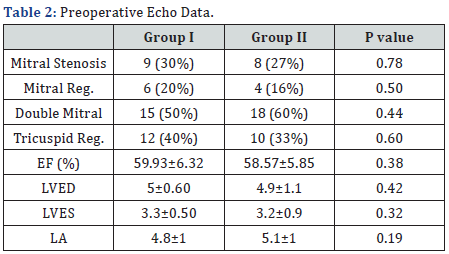

There were no statistically significant differences between Group I and Group II as regards to the patient’s preoperative echo data as shown in Table 2.

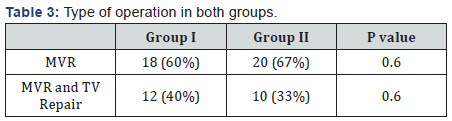

There were no statistically significant differences between Group I and Group II as regards to the type of operation as shown in Table 3.

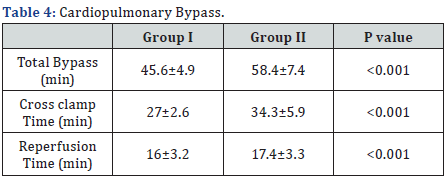

There were statistically significant difference between Group I and Group II as regards to the total bypass, cross clamp and consequently the reperfusion time, all were significantly longer in group II, as shown in Table 4.

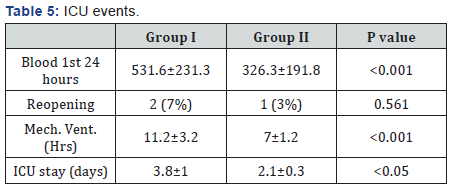

In Group I, blood loss was significantly higher, while in Group II time on mechanical ventilation and ICU stay were significantly less, and there was no significant difference for reopening for bleeding, as shown in Table 5.

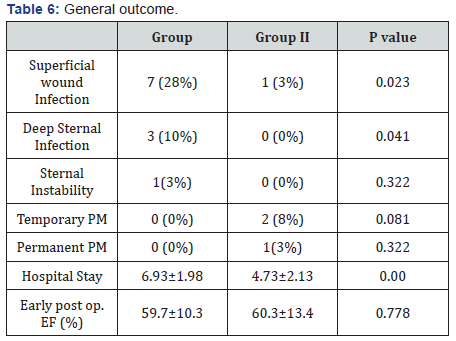

In Group I, superficial wound infection was significantly higher, while in Group II total hospital stay was significantly less. There were no statistically significant difference between Group I and Group II as regards to deep wound infection, sternum instability, the need of temporary or permanent pacemaker and finally the ejection fraction at time of discharge, as shown in Table 6.

Discussion

Mini thoracotomy versus mini sternotomy

In our study we considered the partial or mini sternotomy in Group II as a less invasive cardiac approach, however our study was not concerning with the mini thoracotomy approach, we determined adequate familiar working field with appropriate exposure of mitral valve through a smaller limited incision, which appear to be pretty different in comparison to thoracotomies exposure for cardiac procedure. McClure et al. [6] reported certain degree of variation from patient to patient regarding the relation between the different structures of the heart and the chest wall which is not significant for the surgeon when using large incisions. While with smaller incisions the preference is for the ministernotomy incision [15]. While in mini sternotomy, Hsiao et al. [5] reported that this incision affords the surgeon a familiar operative field from which either mitral valve repair or replacement are possible.

Positioning

In our study all patients were lying in supine, no special position is required for the UPS group. Lehr et al. [11] reported that in minimal invasive mitral valve through minithoractomy, the patient is placed on the operating table in supine position, with the right hemithorax elevated 30 degrees and the hips flat. While minimal invasive through thoractomy partial sternotomy were reported lying in supine, [5,13,14].

Central and peripheral cannulation

In our study the cardio pulmonary bypass was obtained in standard approach by central aortic cannulation in both groups, with no need for peripheral cannulation. Hsiao et al. [5] reported that central aortic and venous cannulation are possible and the ascending aorta can be cross-clamped directly, without the need for endovascular clamping. In contrast with the thoracotomies. The common femoral artery is the most common site for perfusion [11].

Peripheral cannulation

Serious drawbacks were recognized for that technique: peripheral atherosclerosis may preclude cannulation, retrograde dissection or emboli may ensue, and other complications such as postoperative wound infection, hematoma, lymphocele, arteriovenous fistula, or stenosis of the femoral vessels may develop [16]. Wolfe et al. [17] reported ischemic injury to the leg as a documented potential complication of femoral arterial cannulation. The proposed mechanisms for this injury include misidentification of the common femoral artery, cannulation of a small femoral system, excessive perfusion times, unidentified vascular disease within this arterial system, and vascular injury or narrowing after removal of the cannula.

Endoscopic or robotic assistance

Half of the patients in this study received less invasive cardiac surgery via partial sternotomy without endoscopic or robotic help, in their series, it was possible in certain cases to carry on simple techniques by watching only the monitor, but most often the successful repair of the mitral valve required direct vision. Endoscopic or robotic assistance was not required [5].

Special instruments

In our study, there was no need to use long-shafted instruments or a knot-pushing device. There was need for extra cost for the instruments or devices. Same opinion was for Chen-Yuan Hsiao et al. [5] they concluded that less invasive cardiac surgery via partial sternotomy does not need longshafted instruments or a knot-pushing device. a shorter learning period can be expected, and additional cost for specific instruments or devices might not be necessary.

Learning curve of surgical technique

The main impediment to adoption of any new surgical approach is that it requires the learning of a different technique, there was a learning curve involved in developing the technique, which was, however, technically similar to conventional sternotomy [1]. The surgeon can utilize this technique with a very short learning period [5].

Cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) and aortic crossclamping times

Were longer in Partial Sternotomy surgery were also reported in other studies [18,4]. However, Mihaljevic et al. [20] reported significantly shorter aortic cross-clamping and cardiopulmonary bypass times in patients undergoing partial sternotomy. Another opinion was reported by Svensson et al. [1] the Intraoperative support among the patients, ischemic time was slightly longer after a minimally invasive approach (65+/-24 VS 62+/-23minutes, P=0.1), and cardiopulmonary bypass time was equivalent.

Coverso to full sternotomy

There was only one patient (3%) who underwent conversion from partial to full sternotomy due to inadequate exposure for mitral valve. Also Hsiao et al. [5] reported one patient (3%) who underwent conversion from partial to full sternotomy due to inadequate exposure for mitral valve replacement. While Tabata et al. [21] reported that 24 of 907 patients required conversion from upper partial sternotomy because of bleeding, ventricular dysfunction, refractory ventricular arrhythmia, poor exposure, and other causes. Twenty-one of 528 patients required conversion from lower partial sternotomy; none died postoperatively. The authors concluded that conversion from upper sternotomy was associated with serious morbidity and mortality. Mihaljevic et al. [20] when conversion is necessary, partial sternotomy can be easily enlarged to full sternotomy.

Blood loss and need of transfusion

In our study, the blood loss were reported to be significantly higher in Conventional Median Sternotomy, The mean blood loss was 531.6mL (Table 5), Less invasive cardiac surgery through partial sternotomy has been reported to reduce postoperative bleeding, and therefore the less blood transfusion. Many studies support this, outcome [1,15,20,22].

Duration of ICU stay and mechanical ventilation

Patients operated on using minimally invasive surgery present, in general terms, less time on mechanical ventilation than patients operated on in the conventional way with mean ventilation time of 7hrs and less ICU stay of 2.1 Days (Table 5). The majority of authors observe benefits in earlier extubation, better recovery of respiratory function and the reduction of the time spent in intensive care and total time in hospital [20,23- 25]. Also Svensson et al. [1] reported A higher proportion of patients were extubated in the operating room.

Reduction of infections

There were less incidence of superficial and deep wound infection and also sternal instability (Table 6), lesser incidence of infectious complications, with no deep wound infection in our patients in less invasive cardiac surgery was reported [4,23,29].

Cosmetic effects

One of the potential advantages in our study is the cosmetic benefit special for the young females; Brinkman et al. [29] also reported a cosmetic benefit which is one of the great advantages of these approaches in the case of young patients. Also Bonacchi et al. [24] reported that partial sternotomy provided a better cosmetic result.

Need for pacing

In our study, 2 (7%) patient in UPS group need to temporary pace maker for transient instability and only 1 (3%) patient needed permanent pacing, Table 6. José Navia [14], reported Four percent of patients required permanent pacemaker implantation for the postoperative heart block or bradycardia. Also Cosgrove & Gillinov [13], reported two percent of patients needed a permanent pacemaker. While Robert et al. [14] reported four patients had junctional rhythm in the postoperative period, but this did not persist.

Postoperative pain

In our study we noticed the postoperative need of analgesics to be much lesser in the partial sternotomy group, which reflects the potential benefit of pain reduction. Studies reported the reduction of pain felt by the patient and the demand for analgesics in the immediate postoperative period [15,24,30]. Svensson et al. [1] reported less pain in the first 24 hours after the operation (P<.0001) for minimally invasive surgery patients had but similar pain scores thereafter with the conventional. Compared to patients receiving lateral thoracotomy, less pain was reported in patients undergoing partial sternotomy [31].

Duration of hospital stay and functional recovery

One of the objectives of minimally invasive approaches is to reduce surgical aggression and thus favor functional recovery, in ours we found the mean duration of hospitalization was 5.6 (Table 6) in Partial Sternotomy. The benefit of these approaches in terms of the impact on the duration of hospitalization is quite uniform, and the majority of authors observe benefits in the reduction of the average hospital stay [24,25,27,29]. On the other hand Svensson study does not show differences in the duration of the hospitalization [1].

Mortality

In ours there were no mortality in both groups, comparative studies have demonstrated that there are no differences in early mortality between minimally invasive approaches and a complete sternotomy [15], also late outcome Survival at 5, 10, and 15 years was 93%±1%, 86%±1% and 79%±3%, respectively (median survival, 15 years; 95% confidence interval, 14.9-15.4). Freedom from reoperation was 100% for mitral valve replacement at late follow-up [6].

Limitations

There are several limitations in our study. The patient number was limited, and this was a prospective study in one single hospital. Long term functional status and survival follow-up are necessary in any future study, also the first images we can see the cosmetic benefits of the mini-sternotomy technique, as all cardiac surgeries in this study were the first for the patients.

Conclusion

Partial sternotomy is a safe alternative to full sternotomy in mitral valve replacement. It provides adequate and familiarexposure and consequently, a shorter learning period can be expected. Special instruments, endoscopic or robotic assistance, peripheral cannulation are not required, and superior to conventional approach in terms of hospital cost effectiveness and patient satisfaction.

References

- Svensson LG, Atik FA, Cosgrove DM, Blackstone EH, Rajeswaran J, et al. (2010) Minimally invasive versus conventional mitral valve surgery: a propensity-matched comparison. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 139(4): 926-932.

- Cao C, Gupta S, Chandrakumar D, Nienaber TA, Indraratna P, et al. (2013) A meta-analysis of minimally invasive versus conventional mitral valve repair for patients with degenerative mitral disease. Ann Cardiothorac Surg 2(6): 693-703.

- Schmitto JD, Mokashi SA, Cohn LH (2010) Minimally-invasive valve surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol 56(6): 455-462.

- Gammie JS, Zhao Y, Peterson ED, O’Brien SM, Rankin JS, et al. (2010) J. Maxwell Chamberlain Memorial Paper for adult cardiac surgery. Lessinvasive mitral valve operations: trends and outcomes from the Society of Thoracic Surgeons Adult Cardiac Surgery Database. Ann Thorac Surg 90(5): 1401-1410.

- Hsiao CY, Ou-Yang CP, Huang CH (2012) Less invasive cardiac surgery via partial sternotomy. J Chin Med Assoc 75(12): 630-634.

- McClure RS, Athanasopoulos L V, McGurk S, Davidson MJ, Couper GS, et al. (2013) One thousand minimally invasive mitral valve operations: Early outcomes, late outcomes, and echocardiographic follow-up. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 145(5): 1199-1206.

- Cohn LH, Adams DH, Couper GS, Bichell DP, Rosborough DM, et al. (1997) Minimally invasive cardiac valve surgery improves patient satisfaction while reducing costs of cardiac valve replacement and repair. Ann Surg 226(4): 421-428.

- Cosgrove DM, Sabik JF, Navia JL (1998) Minimally invasive valve operations. Ann Thorac Surg 65(6): 1535-1539.

- Grossi EA, Loulmet DF, Schwartz CF, Ursomanno P, Zias EA, et al. (2012) Evolution of operative techniques and perfusion strategies for minimally invasive mitral valve repair. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 143(4 Suppl): S68-S70.

- Galloway AC, Schwartz CF, Ribakove GH, Crooke GA, Gogoladze G, et al. (2009) A Decade of Minimally Invasive Mitral Repair: Long-term outcomes. Ann Thorac Surg 88(4): 1180-1184.

- Lehr EJ, Guy TS, Smith RL, Grossi EA, Shemin RJ, et al. (2016) Minimally Invasive Mitral Valve Surgery III: Training and Robotic-Assisted Approaches. Innovations (Phila) 11(4): 260-267.

- Gillinov AM, Banbury MK, Cosgrove DM (2000) Hemisternotomy approach for aortic and mitral valve surgery. J Card Surg 15(1): 15-20.

- Cosgrove DM, Gillinov AM (1998) Partial Sternotomy for Mitral Valve Operations. Operative Techniques in Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery 3(1): 62-72.

- Tam RK, Ho C, Almeida AA (1998) Minimally invasive mitral valve surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 115(1): 246-247.

- McClure RS, Cohn LH, Wiegerinck E, Couper GS, Aranki SF, et al. (2009) Early and late outcomes in minimally invasive mitral valve repair: an eleven-year experience in 707 patients. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 137(1): 70-75.

- Lamelas J, Williams RF, Mawad M, LaPietra A (2016) Complications Associated With Femoral Cannulation During Minimally Invasive Cardiac Surgery. Ann Thorac Surg pii: S0003-4975(16)31364-9.

- Wolfe JA, Malaisrie SC, Farivar RS, Khan JH, Hargrove WC, et al. (2016) Minimally Invasive Mitral Valve Surgery II: Surgical Technique and Postoperative Management. Innovations (Phila) 11(4): 251-259.

- Doll N, Borger MA, Hain J, Bucerius J, Walther T, et al. (2002) Minimal access aortic valve replacement: effects on morbidity and resource utilization. Ann Thorac Surg 74(4): S1318-S1322.

- Chitwood WR, Elbeery JR, Chapman WH, Moran JM, Lust RL, et al. (1997) Video-assisted minimally invasive mitral valve surgery: the “micro-mitral” operation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 113(2): 413-414.

- Mihaljevic T, Cohn LH, Unic D, Aranki SF, Couper GS, et al. (2004) One Thousand Minimally Invasive Valve Operations. Ann Surg 240(3): 529- 534.

- Tabata M, Umakanthan R, Khalpey Z, Aranki SF, Couper GS, et al. (2004) Conversion to full sternotomy during minimal-access cardiac surgery: reasons and results during a 9.5-year experience. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 134(1): 165-169.

- Cheng DCH, Martin J, Lal A, Diegeler A, Folliguet TA, et al. (2011) Minimally invasive versus conventional open mitral valve surgery: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Innovations (Phila) 6(2): 84-103.

- Grossi EA, Galloway AC, Ribakove GH, Zakow PK, Derivaux CC, et al. (2001) Impact of minimally invasive valvular heart surgery: a casecontrol study. Ann Thorac Surg 71(3): 807-810.

- Bonacchi M, Prifti E, Giunti G, Frati G, Sani G (2002) Does ministernotomy improve postoperative outcome in aortic valve operation? A prospective randomized study. Ann Thorac Surg 73(2): 460-466.

- Moustafa MA, Abdelsamad AA, Zakaria G, Omarah MM (2007) Minimal vs median sternotomy for aortic valve replacement. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann 15(6): 472-475.

- Liu J, Sidiropoulos A, Konertz W (1999) Minimally invasive aortic valve replacement (AVR) compared to standard AVR. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 16 Suppl 2: S80-S83.

- Grossi EA, Galloway AC, Ribakove GH, Buttenheim PM, Esposito R, et al. (1999) Minimally invasive port access surgery reduces operative morbidity for valve replacement in the elderly. Heart Surg Forum 2(3): 212-215.

- Glower DD, Landolfo KP, Clements F, Debruijn NP, Stafford-Smith M, et al. (1998) Mitral valve operation via Port Access versus median sternotomy. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 14 Suppl 1: S143-S147.

- Brinkman WT, Hoffman W, Dewey TM, Culica D, Prince SL, et al. (2010) Aortic valve replacement surgery: comparison of outcomes in matched sternotomy and PORT ACCESS groups. Ann Thorac Surg 90(1): 131- 135.

- Candaele S, Herijgers P, Demeyere R, Flameng W, Evers G (2003) Chest pain after partial upper versus complete sternotomy for aortic valve surgery. Acta Cardiol 58(1): 17-21.

- Casselman FP, Van Slycke S, Dom H, Lambrechts DL, Vermeulen Y, et al. (2003) Endoscopic mitral valve repair: feasible, reproducible, and durable. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 125(2): 273-282.