- Review Article

- Introduction

- Heart Failure with Left Ventricle Systolic Dysfunction (LVSD)

- Heart Failure with Midrange Left ventricle Ejection fraction (40-49%) in Afro Caribbean Population

- Heart Failure with Reduced Left Ventricle Ejection Fraction (<40%) in Afro Caribbean Population

- Heart Failure with Normal (HFNEF or HFpEF), Midrange (HFmrEF) and Heart Failure with reduced (HFrEF) Ejection Fraction-An integrative hypothesis about the natural history of heart failure in afro Caribbean patients

- References

Heart Failure in Afro-Caribbean: A Cardiovascular Enigma

Felix Nunura*

Division of Cardiovascular Medicine, Heart Institute of the Caribbean, Jamaica

Submission: February 05, 2017; Published: February 27, 2017

*Corresponding author: Felix Nunura, Division of Cardiovascular Medicine, Heart Institute of the Caribbean, 23 Balmoral Ave, Kingston, Jamaica, Tel:1876 8797031 ;Email: fnunura@caribbeanheart.com

How to cite this article: Nunura Felix. Heart Failure in Afro-Caribbean: A Cardiovascular Enigma. J Cardiol & Cardiovasc Ther 2017; 3(3): 555611. DOI: 10.19080/JOCCT.2017.03.555611

Abbrevations:HF: Heart Failure; MESA: Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis; IHD: Ischemic Heart Disease; EF: Ejection Fractions; CHD: Coronary Heart Disease; PAD: Peripheral Arterial Disease; CVD: Cardiovascular Disease; LVEF: Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction; LVSD: Left Ventricle Systolic Dysfunction; HHD: Hypertensive Heart Disease; MI: Myocardial Infarction; DCM: Dilated Cardiomyopathy; DHHD: Dilated Hypertensive Heart Disease; IHD: Ischemic Heart Disease; CRT: Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy; HTN: Hypertension; SHF: Systolic Heart Failure; DM: Diabetes Mellitus; ACEIs: Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitors

- Review Article

- Introduction

- Heart Failure with Left Ventricle Systolic Dysfunction (LVSD)

- Heart Failure with Midrange Left ventricle Ejection fraction (40-49%) in Afro Caribbean Population

- Heart Failure with Reduced Left Ventricle Ejection Fraction (<40%) in Afro Caribbean Population

- Heart Failure with Normal (HFNEF or HFpEF), Midrange (HFmrEF) and Heart Failure with reduced (HFrEF) Ejection Fraction-An integrative hypothesis about the natural history of heart failure in afro Caribbean patients

- References

Introduction

Heart failure is a disease in which there are striking population differences in almost every aspect of the disease. It has been recognized that the cause of heart failure is predominantly ischemic disease in nonblack but is related primarily to hypertension in blacks and this statement should be also assessed in Afro-Caribbean patients because population differences in disease exist that may be attributable to differences in social factors, genetics, environment, lifestyle, comorbidities, and complex interactions among these factors.

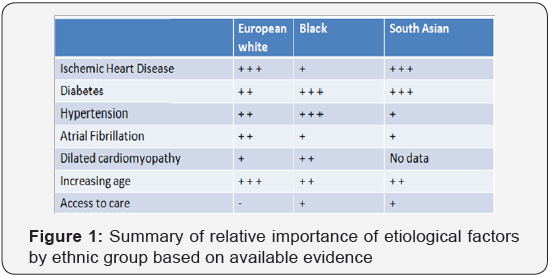

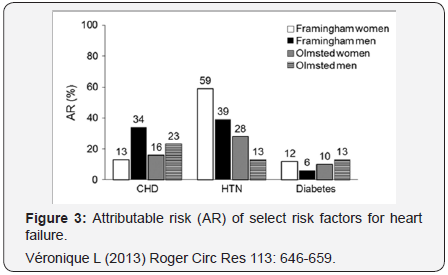

The full impact of cardiovascular disease risk factors on incident disease and cardiovascular mortality in the Caribbean community is still not known, as there are not longitudinal studies on incident or fatal cardiovascular disease [1]. Data from St James Study in Trinidad showed that Blood Pressure, diabetes and low density lipoprotein were independent predictors of coronary heart disease in men [2] while data from the Barbados Registry of Stroke showed that of the patients with incident Stroke in Barbados, 68% had a history of hypertension and 38% had Diabetes [3], however we lack of local information on the incidence of heart failure (HF) in the Afro-Caribbean community. There are several population based studies of HF in Afro-Caribbean in the UK. A re-analysis of a hospital based audit in Birmingham [4] indicates that the risk of HF for African Caribbean, compared to Europeans, in those aged 60-79 years was 3.1 (95% confidence limits 1.9 to 4.9). In adult African Americans the prevalence of HF has been estimated at 3%-higher than white counterparts [5]. This is not explained by coronary artery disease, as the prevalence of CAD (Figure 1) is lower in black patients with HF [6]. Both the prevalence of the risk factor and its associated risk for the outcome are needed to determine the population impact of a risk factor on a disease. Coronary disease, hypertension, diabetes, obesity, and smoking has been each associated with an increased risk for HF (Figure 2 & 3), but the Population Attributable Risk -PAR- has been shown to be greatest for coronary disease (20%) and hypertension (20%) in the Olmsted County Study [7]. Again, data on the burden of HF in diverse populations are scarce.

In ARIC and in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA), HF incidence was higher in blacks than in whites. In both studies, the difference between blacks and whites was attenuated after adjustment and overall the greater HF incidence in blacks was related to their greater burden of atherosclerotic risk factors as well as to socioeconomic status [8,9]. Data on the incidence and prevalence of HF according to EF and how it may have changed over time are very limited. The available evidence suggests that the prevalence of HF with preserved EF increased over time [10]. Studies of Caribbean Heart Failure are scarce. In the only study of Heart Failure (n=100), published ten years ago in a private practice in Jamaica, GR Lalljie & SE Lalljie [11] reported that most patients were over 65 years of age, female, never smoked cigarettes, overweight/obese and hypertensive (82%). The main etiologies were hypertension (54%) and ischemic heart disease (IHD) (26%). Ninety-one per cent were in sinus rhythm and 6% in atrial fibrillation.

Forty-nine per cent had echocardiograms, of these 39% had ejection fractions (EF) >40%, 34% had EF 21-40% and 27% had EF <20%. Hypertensive heart disease was found in 54%, hypertensive cardiomyopathy in 14% and ischemic heart disease in 26%. According to the most recent census, conducted in 2011, the majority of Jamaicans identify as black [12] the ethnic groups are [13]: Black (92.1%), Mixed (6.1%), Asian (0.8%), other (0.4 %). Much of Jamaica’s black population is of African or partially African descent with many being able to trace their origins to West Africa. It has been previously observed that Coronary Heart Disease (CHD) and Peripheral Arterial Disease (PAD) are less prevalent among Afro-Caribbean compared to Caucasian and South East Asian ethnic groups. The prevalence of CHD range from 0-7% in Afro-Caribbean to 2-22% in Caucasians.

Strokes are more common among Afro-Caribbean, unfortunately, there are inadequate data on morbidity and mortality from cardiovascular disease (CVD), particularly across the socio-economic gradient, in Afro-Caribbean populations [14]. Previous study of the Jamaican prevalence of hypertension estimated HTN in 30.8% in the 15-and-over age group [15]; however a more recent study has shown that the prevalence estimates for traditional CVD risk factors are: hypertension, 25%; diabetes, 8%; hypercholesterolemia, 12%; obesity, 25%; smoking 15%. [1]. Therefore it is obvious that the burden of cardiovascular disease risk factors in Jamaica And in comparison in parallel with other communities of the Caribbean remains very high. Evidence-based therapies for heart failure (HF) differ significantly according to left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF). However, few data are available on the phenotype and prognosis of patients with HF with midrange LVEF of 40% to 55% (HFmrEF), and the impact of recovered systolic function on the clinical features, functional capacity, and outcomes of this population is not known [16]. Previous investigations in American [17] and Chinese [18] populations have demonstrated that subjects with HF and a normal EF (>55%) -HFNEF, differ in their clinical and demographic characteristics from subjects with mildly (40% to 55%) and severely (<40%) decreased EF. Differentiation of patients with HF based on LVEF is important due to different underlying etiologies, demographics, comorbidities and response to therapies [19] however there are not comparative research among Afro-Caribbean patients with HF with midrange EF (HFmrEF) vs HF with reduced EF (HFrEF).

- Review Article

- Introduction

- Heart Failure with Left Ventricle Systolic Dysfunction (LVSD)

- Heart Failure with Midrange Left ventricle Ejection fraction (40-49%) in Afro Caribbean Population

- Heart Failure with Reduced Left Ventricle Ejection Fraction (<40%) in Afro Caribbean Population

- Heart Failure with Normal (HFNEF or HFpEF), Midrange (HFmrEF) and Heart Failure with reduced (HFrEF) Ejection Fraction-An integrative hypothesis about the natural history of heart failure in afro Caribbean patients

- References

Heart Failure with Left Ventricle Systolic Dysfunction (LVSD)

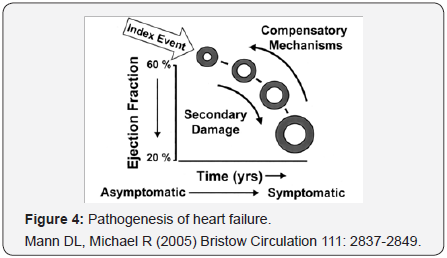

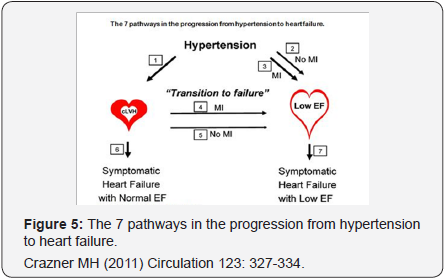

Heart failure (HF) is usually a progressive condition (Figure 4) that begins with risk factors for LV dysfunction (e.g., hypertension), proceeds to asymptomatic changes in cardiac structure (e.g., LV hypertrophy) and function (e.g., impaired relaxation), and then evolves into clinically overt HF, disability and death [20]. It is difficult to know in which proportion hypertensive patients evolved towards one of the different possibilities of Hypertensive heart disease (HHD). It is now well recognized that clinical heart failure can occur either in the setting of reduced LVEF or normal-preserved-LVEF. The potential progression of asymptomatic LV dysfunction to clinical heart failure in Hypertensive patients has been elegantly reviewed by Drazner [21]. He has proposed seven possible pathways in the progression from hypertension to heart failure (Figure 5): Hypertension progresses to concentric (thick-walled) LVH (cLVH; pathway 1). The direct pathway from hypertension to Dilated Cardiac Failure-DCF (increased LV volume with reduced LVEF) can occur without (pathway 2) or with (pathway 3) an interval myocardial infarction (MI).

Concentric hypertrophy progresses to dilated cardiac failure (transition to failure) most commonly via an interval myocardial infarction (pathway 4). Recent data suggest that it is not common for concentric hypertrophy to progress to DCF without interval myocardial infarction (pathway 5) and patients with concentric LVH can develop symptomatic heart failure with a preserved LVEF (pathway 6), or patients with DCF can develop symptomatic heart failure with reduced LVEF (pathway 7). There are other influences of other important modulators of the progression of hypertensive heart disease, including obesity, diabetes mellitus, age, environmental exposures, and genetic factors. Hypertensive heart disease simulating dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) has been previously documented [22], these patients had past history of hypertension and prominent left ventricular dilatation with reduced left ventricular contractility, but no left ventricular wall thickening. Among cases reported by Lalljie [11] 14% were considered as Hypertensive cardiomyopathy. In what proportion and for what reason, pathophysiological, biological or ethnic, some Afro-Caribbean patients, almost all of them hypertensive with or without diabetes, develop Dilated Cardiac Failure with severe LVSD but with normal epicardial coronary arteries (angiographically proven) and how many of them with the same risk profile develop non-ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy -NIDCM (angiographically proven) is a topic that we do not know and that deserves to be considered and investigated. In short, the consideration of a direct pathway from Hypertension to dilated hypertensive heart disease (DHHD) seems to be plausible. From another point of view, perhaps not all patients considered DHHD hypertensive are really a form of Hypertensive heart disease. In 211 Afro-Caribbean patients with heart failure presenting to St George’s Hospital Heart Failure clinic [23] the most common cause of heart failure was nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy (NIDCM) in 27.5% (whites, 19.9%; P<0.001). Lower rates of ischemic cardiomyopathy were observed (13% versus 41%; P<0.001). Interesting, the fourth most common cause of heart failure in Afro-Caribbean living in UK, was cardiac amyloidosis (11.4%). Since Caribbean countries do not routinely perform testing for cardiac amyloidosis (ATTR V122I), it is possible that some of these subjects with DHHH or NIDCM may be confused with other etiologies. According with Dungu et al. [24] about 4% of African-Americans possess the V122I variant of transthyretin, associated with cardiac amyloidosis (ATTR) and ten percent of Afro-Caribbean heart failure population have ATTR V122I, often misdiagnosed as hypertensive heart disease (HHD), however, they founded that differential diagnosis of ATTR V122I over HHD could be strongly supported when the ventricular septum thickness exceeds precordial voltage [24].

- Review Article

- Introduction

- Heart Failure with Left Ventricle Systolic Dysfunction (LVSD)

- Heart Failure with Midrange Left ventricle Ejection fraction (40-49%) in Afro Caribbean Population

- Heart Failure with Reduced Left Ventricle Ejection Fraction (<40%) in Afro Caribbean Population

- Heart Failure with Normal (HFNEF or HFpEF), Midrange (HFmrEF) and Heart Failure with reduced (HFrEF) Ejection Fraction-An integrative hypothesis about the natural history of heart failure in afro Caribbean patients

- References

Heart Failure with Midrange Left ventricle Ejection fraction (40-49%) in Afro Caribbean Population

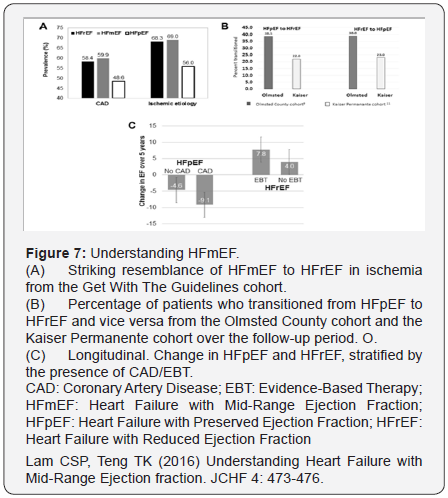

Patients with an LVEF in the range of 40-49% represent a ‘grey area’: The current HF Guidelines have mentioned that identifying HFmrEF as a separate group can stimulate research into the underlying characteristics, pathophysiology and treatment of this group of patients (Figures 6&7). Patients with HFmrEF most probably have primarily mild systolic dysfunction, but with features of diastolic dysfunction [25]. Aging has been associated with diastolic dysfunction. On the other hand, in a cohort of Chinese patients [18] with mildly decreased EF (40% to 55%), despite the only mildly dilated left ventricular dimensions by 2-dimensional echocardiography, they had significant ventricular remodeling (e.g., rightward shift in end-diastolic pressure–volume relation) and decreases in chamber contractility. The researchers comment that this is markedly different from the physiologic parameters displayed in the cohort with HF and EF >55%, and more similar to the phenotype observed in patients with overt systolic HF (with an EF <40%). Nadruz et al. [16] have concluded that patients with HF with midrange LVEF demonstrate a distinct clinical profile from HFpEF and HFrEF patients, with objective measures of functional capacity similar to HFpEF. Within the midrange LVEF HF population, recovered systolic function is a marker of more favorable prognosis. With current understanding, HFmrEF is distinct from HFrEF (EF < 40%) simply because there is no evidence-based therapy, and distinct from HFpEF (EF ≥ 50%) simply because EF is not preserved [26]. For now we do not have information on this new category in the Afro-Caribbean community.

- Review Article

- Introduction

- Heart Failure with Left Ventricle Systolic Dysfunction (LVSD)

- Heart Failure with Midrange Left ventricle Ejection fraction (40-49%) in Afro Caribbean Population

- Heart Failure with Reduced Left Ventricle Ejection Fraction (<40%) in Afro Caribbean Population

- Heart Failure with Normal (HFNEF or HFpEF), Midrange (HFmrEF) and Heart Failure with reduced (HFrEF) Ejection Fraction-An integrative hypothesis about the natural history of heart failure in afro Caribbean patients

- References

Heart Failure with Reduced Left Ventricle Ejection Fraction (<40%) in Afro Caribbean Population

Heart failure (HF) has been singled out as an epidemic and is a staggering clinical and public health problem, associated with significant mortality, morbidity, and healthcare expenditures, particularly among those aged ≥65 years. The case mix of HF is changing over time with a growing proportion of cases presenting with preserved ejection fraction for which there is no specific treatment. (30 In the E-ECHOES Study [27] of Prevalence of Heart Failure and Atrial Fibrillation in Minority Ethnic Subjects 17 Afro Caribbean -AC, (0.89%; 95% CI 0.52 to 1.42%) had an LVEF <40% with a mean age of 72.4 years (SD 11.0), of which 15 (88.24%) were males. The proportion of patients with hypertension was 57.9% and diabetes 26.3%. Just 1.36% Afro-Caribbean patients of this cohort had evidence of atrial fibrillation with a mean CHADS2 score of 2.3. Assigning a cause to HF should be envisioned while focusing on clinically ascertained risk factors and acknowledging that multiple causes for HF often coexist and interact in a given patient [28]. It has been established that the etiology of HF is diverse within and among world regions. There is no agreed single classification system for the causes of HF, with much overlap between potential categories (Diseases Myocardium, Abnormal loading conditions or Arrhythmias). Many patients will have several different pathologies-cardiovascular and non-cardiovascularthat conspire to cause HF. Indeed, the Identification of these diverse pathologies should be part of the diagnostic workup, as they may offer specific therapeutic opportunities. Many patientswith HF and ischemic heart disease (IHD) have a history of myocardial infarction or revascularization. However, a normal coronary angiogram does not exclude myocardial scar (e.g. by CMR imaging) or impaired coronary microcirculation as alternative evidence for IHD [25].

The prevalence and incidence of left bundle branch block in Afro-Caribbean patients with HFrEF is not well known and must be assessed as it could underlines the importance of Myocardium Diseases in the Afro-Caribbean population . It has been widely studied that LBBB may occur in asymptomatic individuals, patients with extensive myocardial infarction, and in those with heart failure, especially in dilated, non-ischemic cardiomyopathies. In some patients, LBBB (sometimes rate dependent) may be the first manifestation of heart disease whereas the clinical presentation of a dilated cardiomyopathy develops only some years later [29]. The fact that a proportion of Afro-Caribbean patients with HFrEF have wide QRS complex (LBBB), should stimulate to consider more resources directed to Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy (CRT) in the Caribbean community as CRT has been recommended for symptomatic patients with HF in sinus rhythm with a QRS duration ≥150msec and LBBB QRS morphology and with LVEF ≤35% despite OMT, in order to improve symptoms and reduce the HF morbidity and mortality [25].

- Review Article

- Introduction

- Heart Failure with Left Ventricle Systolic Dysfunction (LVSD)

- Heart Failure with Midrange Left ventricle Ejection fraction (40-49%) in Afro Caribbean Population

- Heart Failure with Reduced Left Ventricle Ejection Fraction (<40%) in Afro Caribbean Population

- Heart Failure with Normal (HFNEF or HFpEF), Midrange (HFmrEF) and Heart Failure with reduced (HFrEF) Ejection Fraction-An integrative hypothesis about the natural history of heart failure in afro Caribbean patients

- References

Heart Failure with Normal (HFNEF or HFpEF), Midrange (HFmrEF) and Heart Failure with reduced (HFrEF) Ejection Fraction-An integrative hypothesis about the natural history of heart failure in afro Caribbean patients

According with Sanderson [30], HFrEF is mainly due to myocardial infarction or dilated cardiomyopathy that rapidly damages the myocardium, whereas in HFNEF (HFpEF), the effects of hypertension (HTN), diabetes, and aging are slower and would explain why some measurement of LV mechanics (i.e. long-axis function, which is a more sensitive measure) can be reduced while EF remains “normal”. He emphasizes that cardiologists working in Africa, East Asia, and India often can see patients with HFrEF who have only HTN as a risk factor, and presumably these patients passed through an HFpEF (HFNEF) phase, however other risk factors may interact, including alcohol intake, which has experimentally-induced HFrEF with a typical dilated LV with low EF in spontaneously hypertensive rats with pre-existing LV hypertrophy and a normal or supranormal EF). Accordingly, the Time course and pattern of development of heart failure (Figure 8) is primarily caused by myocardial infarction (MI), with pronounced remodeling and shape change leading to systolic heart failure (SHF), and HF primarily caused by hypertension (HT), with or without diabetes mellitus (DM), leading to heart failure with , initially, a normal ejection fraction (HFNEF). Patients with a history of MI and patients with HTN may experience periods of HFNEF and finally they develop systolic heart failure with a reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF). Assuming that the Afro American Heart Failure data could be applied to the Afro-Caribbean community it appears that HF in this region to be of worse severity that HF in white patients. The clinical experience suggests that at the time of diagnosis, left ventricular function seems to be more severely impaired and the clinical class is more advanced. There is no doubt that the strongest risk factor for heart failure in Afro-Caribbean seems to be hypertension, which is both more prevalent and more pathologic in Afro-Caribbean population. It is likely that heart failure represents an important end organ effect of hypertension. When affected by heart failure, Afro-Caribbean might experience a greater rate of hospitalization and may be exposed to a higher mortality risk as well. Genomic medicine has yielded a number of candidate single nucleotide polymorphisms that might contribute to the excess pathogenicity of heart failure in African Americans [31], but much more work needs to be done in larger cohorts. Effective therapy of heart failure must start with the recognition of the different manifestations of heart failure in African Caribbean.

An increased awareness of the risk of hypertension followed by early and effective intervention may reduce the risk of heart failure in this population. The SOLVD Registry [32] was the first trial to demonstrate a significant difference in the putative etiology of LV dysfunction in African Americans with heart failure. It is reasonable to assume that documented ischemic heart disease as a cause of heart failure occurs less frequently in the African Caribbean patient than other groups of patients, an observation that was also initially put forward by analysis of the SOLVD Registry. In summary, Afro-Caribbean hypertensive patients would evolve for an initial phase with normal EF (HFNEF or HFpEF) and depending on the associated pathophysiological and risk factors or the severity of hypertensive cardiovascular disease they eventually develop systolic dysfunction, initially mild (HFmrEF) and finally severe ( HFrEF). The impact of an effective therapy (OMT) on reverse remodeling may further change this complex final outcome.

After The Vasodilator–Heart Failure Trials I and II, there remain many promises and unanswered questions regarding Hydralazine-Isorbide Dinitrate (H-ISDN) therapy in heart failure, ranging from efficacy and mechanism of action to defining optimal patient population and timing of therapy [33]. It had already been confirmed (Figure 9) a lesser response to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) and β-blockers in lowering blood pressure in black versus nonblack hypertensives [34], but (Figure 10) The African-American Heart Failure Trial (A-HeFT) found that the addition of a fixed-dose combination of isosorbide dinitrate/hydralazine to standard neurohormonal blockade resulted in a 43% improvement in survival, a 33% reduction in hospitalizations for heart failure, and significant improvement in quality of life measured with the Minnesota Living With Heart Failure questionnaire [35]. These striking improvements in outcomes occurred in patients welltreated with standard neurohormonal blockade, including ACE inhibition, angiotensin receptor blockade, and β-blockade. This outcome suggested that alternative or additional mechanisms of progression of heart failure, perhaps related to impaired nitric oxide availability, were present in this population and were treated by this combination. Considering the persistent suboptimal outcomes and a significant opportunity for improvement in therapy for these patients, further research related to the use of H-ISDN in heart failure in Afro-Caribbean population seems warranted.

In summary, Heart failure is a disease in which there are striking population differences in almost every aspect of the disease. It has been recognized that the cause of heart failure is predominantly ischemic disease in nonblack but is related primarily to hypertension in blacks [36] and this statement should be also confirmed in Afro-Caribbean patients because population differences in disease exist that may be attributable to differences in social factors, genetics, environment, lifestyle, co-morbidities, and complex interactions among these factors. The term African Caribbean needs to be defined and restricted to an African descent person originating from the Caribbean. The concept of ethnicity encapsulates cultural, behavioral, and environmental factors that increase the risk of disease; hence it is crucial in epidemiology and public health [37]. When population differences are observed, focused studies are warranted to identify the contribution of these factors (including biological, environmental, social, genetic, and lifestyle factors and their interactions) and how best to treat them. Identification and study of population differences may enhance disease treatment in all populations and additionally may provide disparity-reducing benefit for populations with poorer health outcomes [38-40].

- Review Article

- Introduction

- Heart Failure with Left Ventricle Systolic Dysfunction (LVSD)

- Heart Failure with Midrange Left ventricle Ejection fraction (40-49%) in Afro Caribbean Population

- Heart Failure with Reduced Left Ventricle Ejection Fraction (<40%) in Afro Caribbean Population

- Heart Failure with Normal (HFNEF or HFpEF), Midrange (HFmrEF) and Heart Failure with reduced (HFrEF) Ejection Fraction-An integrative hypothesis about the natural history of heart failure in afro Caribbean patients

- References

References

- Ferguson TS, Francis DK, Tulloch-Reid MK, Younger NO, McFarlane SR, et al. (2011) An Update on the Burden of Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors in Jamaica-Findings from the Jamaica Health and Life style Survey 2007-2008. West Indian Med J 60(4): 422-428.

- Miller GJ, Beckles GL, Maude GH, Carson DC, Alexis SD, et al. (1989) Ethnicity and other characteristics predictive of coronary heart disease in a developing community: principal results of the St James survey, Trinidad. Int J Epidemiol 18(4): 808-817.

- Corbin DO, Poddar V, Hennis A, Gaskin A, Rambarat C, et al. (2004) Incidence and case fatality rates of first-ever stroke in a black Caribbean Population: The Barbados Registry of Strokes. Stroke 35(6): 1254-1258.

- Lip G, Zarifis J, Beevers DG (1997) Acute admissions with heart failure to a district general hospital serving a multiracial population. Int J Clin Pract 51(4): 223-227.

- (1996) Congestive heart failure in the United States: a new epidemic [data fact sheet] Bethesda, Md: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Information Center, USA.

- Dries DL, Exner DV, Gersh BJ, Cooper HA, Carson PE, et al. (1999) Racial differences in the outcome of left ventricular dysfunction. N Eng J Med 340(8): 609-616.

- Dunlay SM, Weston SA, Jacobsen SJ, Roger VL (2009) Risk Factors for Heart Failure: A Population-Based Case-Control Study. Am J Med 122(11): 1023-1028.

- Loehr LR, Rosamond WD, Chang PP, Folsom AR, Chambless LE (2008) Heart failure incidence and survival (from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study). Am J Cardiol 101(7): 1016-1022.

- Bahrami H, Kronmal R, Bluemke DA, Olson J, Shea S, et al. (2008) Differences in the incidence of congestive heart failure by ethnicity: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Arch Intern Med 168(19): 2138-2145.

- Owan TE, Hodge DO, Herges RM, Jacobsen SJ, Roger VL, et al. (2006) Trends in prevalence and outcome of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med 355(3): 251-259.

- Lalljie GR, Lalljie SE (2007) Characteristics, Treatment and Short- Term Survival of Patients with Heart Failure in a Cardiology Private Practice in Jamaica. West Indian Med J 56(2): 139-143.

- https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/ geos/jm.html

- (2015) The CIA World Factbook, Jamaica.

- Francis DK, Bennett NR, Ferguson TS, Hennis AJ, Wilks RJ, et al. (2015) Disparities in cardiovascular disease among Caribbean populations: a systematic literature review. BMC Public Health 15: 828.

- Ragoobirsingh D, McGrowder D, Morrison EY, Johnson P, Lewis-Fuller E, et al. (2002) The Jamaican hypertension prevalence study. J Natl Med Assoc 94(7): 561-565.

- Nadruz W, West E, Santos M, Skali H, Groarke JD, et al. (2016) Heart Failure and Midrange Ejection Fraction: Implications of Recovered Ejection Fraction for Exercise Tolerance and Outcomes. Circ Heart Fail 9(4): e002826.

- Sweitzer NK, Lopatin M, Yancy CW, Mills RM, Stevenson LW (2008) Comparison of clinical features and outcomes of patients hospitalized with heart failure and normal ejection fraction (>l =55%) versus those with mildly reduced (40% to 55%) and moderately to severely reduced (<40%) fractions. Am J Cardiol 101(8): 1151-1156.

- He KL, Burkhoff D, Leng WX, Liang ZR, Fan L, et al. (2009) Comparison of Ventricular Structure and Function in Chinese Patients With Heart Failure and Ejection Fractions >55% Versus 40% to 55% Versus <40. Am J Cardiol 103(6): 845-851.

- Butler J, Fonarow GC, Zile MR, Lam CS, Roessig L, et al. (2014) Developing therapies for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: current state and future directions. JACC Heart Fail 2(2): 97-112.

- Hunt SA, Abraham WT, Chin MH, Feldman AM, Francis GS, et al. (2005) ACC/AHA 2005 guideline update for the diagnosis and management of chronic heart failure in the adult. A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines (Writing Committee to Update the 2001 Guidelines for the Evaluation and Management of Heart Failure): developed in collaboration with the American College of Chest Physicians and the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation 112(12): e154-235.

- Drazner MH (2011) The Progression of Hypertensive Heart Disease. Circulation 123(3): 327-334.

- Takarada A, Yokota Y, Kumaki T, Toh S, Seo T, et al. (1985) Hypertensive heart disease simulating dilated cardiomyopathy. J Cardiogr 15(4): 1015-1026.

- Dungu JN, Papadopoulou SA, Wykes K, Mahmood I, Marshall J, et al. (2016) Afro-Caribbean Heart Failure in the United Kingdom: Cause, Outcomes, and ATTR V122I Cardiac Amyloidosis. Circ Heart Fail 9(9): e003352.

- Dungu J, Valencia O, Baltabaeva A, Antonios T, Hawkins PN, Anderson LJ, et al. (2012) Differentiating hypertensive heart disease and cardiac transthyretin isoleucine 122 (V122l) amyloidosis in Afro-Caribbean patients. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 59(13). DOI: 10.1016/S0735-1097(12)61575-7.

- Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, Bueno H, Cleland JG, et al. (2016) 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure The Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 37(27): 2129-2200.

- Land LH (2016) Heart failure with midrange Ejection Fraction-New opportunities. J Card Fail 22(10): 769-771.

- Gill PS, Calvert M, Davis R, Davies MK, Freemantle N, et al. (2011) Prevalence of Heart Failure and Atrial Fibrillation in Minority Ethnic Subjects: The Ethnic-Echocardiographic Heart of England Screening Study (E-ECHOES). PLoS One 6(11): e26710.

- Veronique LR (2013) Epidemiology of Heart Failure. Circulation Research 113(6): 646-659.

- Schneider JF, Thomas HE, Kreger BE, McNamara PM, Kannel WB (1979) Newly acquired left bundle-branch block: The Framingham study. Ann Intern Med 90(3): 303-310.

- Sanderson JE (2014) HFNEF, HFpEF, HF-PEF, or DHF What is in an Acronym? JACC: Heart Fail 2(1): 93-94.

- Yancy CW, Strong M (2004) The natural history, epidemiology, and prognosis of heart failure in African Americans. Congestive Heart Failure 10(1): 15-18.

- Bourassa MG, Gurne O, Bangdiwala SI, Ghali JK, Young JB, et al. (1993) Natural history and patterns of current practice in heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 22(4 Suppl A): 14A-19A.

- Cole RT, Kalogeropoulos AP, Georgiopoulou VV, Gheorghiade M, Quyyumi A, et al. (2011) Hydralazine and Isosorbide Dinitrate in Heart Failure: Historical Perspective, Mechanisms, and Future Directions. Circulation 123(21): 2414-2422.

- Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, et al. (2003) The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA 289(19): 2560-2572.

- Taylor AL, Ziesche S, Yancy C, Carson P, D’Agostino R, et al. (2004) Combination of isosorbide dinitrate and hydralazine in blacks with heart failure. N Engl J Med 351(20): 2049-2057.

- Yancy CW (2000) Heart failure in African-Americans: a cardiovascular enigma. J Card Fail 6(3): 183-186.

- Agyemang C, Bhopal R, Bruijnzeels M (2005) Negro, Black, Black African, African Caribbean, African American or what? Labelling African origin populations in the health arena in the 21st century. J Epidemiol Community Health 59(12): 1014-1018.

- Taylor AL, Wright JT (2005) Should ethnicity serve as the basis for clinical trial design? Importance of Race/Ethnicity in Clinical Trials. Lessons From the African-American Heart Failure Trial (A-HeFT), the African-American Study of Kidney Disease and Hypertension (AASK), and the Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT). Circulation 112(23): 3654-3666.

- Gottdiener JS, Bednarz J, Devereux R, Gardin J, Klein A (2004) American Society of Echocardiography Recommendations for Use of Echocardiography in Clinical Trials. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 17(10): 1086-1119.

- Bibbins-Domingo K, Pletcher MJ, Lin F, Vittinghoff E, Gardin JM (2009) Racial Differences in Incident Heart Failure among Young Adults. N Engl J Med 360(12): 1179-1190.