Abstract

Klebsiella pneumoniae is a versatile pathogen capable of causing infections in multiple species, yet its role in bovine mastitis remains underexplored. Although well known for hospital-acquired infections in humans, K. pneumoniae also affects dairy animals, leading to substantial economic losses. Its ability to acquire multiple antibiotic resistance (AR) determinants under selective pressure has contributed to the emergence of multidrug-resistant (MDR) and extensively drug-resistant (XDR) strains. Recent data indicate a rapid evolution and global dissemination of pathogenic Klebsiella lineages. In dairy herds, mastitis caused by Klebsiella spp. is increasingly difficult to manage due to the pathogen’s virulence factors and efficient uptake of plasmid-mediated AR genes. Despite these concerns, the veterinary impact of K. pneumoniae has received limited attention. This review summarizes the epidemiology of K. pneumoniae in bovine mastitis and its AR acquisition mechanisms, emphasizing the urgent need for improved surveillance and targeted interventions to address this growing threat to animal and public health.

Keywords:K. pneumoniae; Mastitis; Pathogenicity; Virulence; Prevalence

Introduction

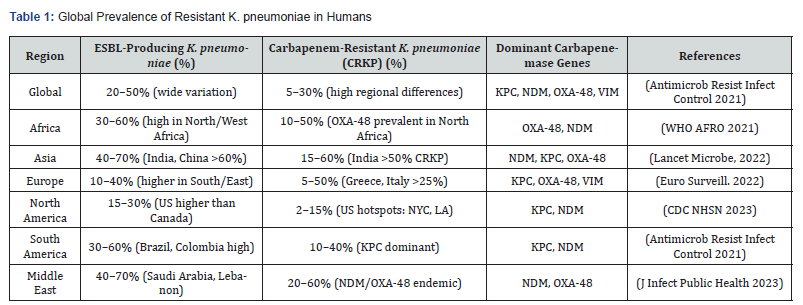

Klebsiella pneumoniae is an opportunistic pathogen responsible for a wide range of diseases in both animals and humans, including pneumonia, urinary tract infections, bacteremia, and liver abscesses [1,2]. Although extensive research has focused on K. pneumoniae infections in both clinical and hospital settings, the emergence of hyper virulent strains showing resistance to a broad range of antibiotics poses a serious challenge to health [3]. The development of antibiotic resistance (AR) is a multifaceted and complex phenomenon resulting from evolution in response to concomitant selective antibiotic pressure. This continuous use and frequent misuse of antibiotics over the last 80 years have resulted in the emergence of extremely drug-resistant (XDR) and multidrug-resistant (MDR) isolates of pathogenic bacteria. Recently, AR has become a world health problem and is particularly in underdeveloped countries, including Pakistan, where insufficient infection control measures further aggravate the issue. Recently, researchers reported a dramatic increase in AR among different bacterial species isolated in Pakistan [4-13]. However, despite these rising issues, epidemiological data regarding MDR K. pneumoniae in infecting animals is limited, as summarized in Table 1.

Abbreviations: CRKP, carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae; ESBL, extended-spectrum beta-lactamase; US, United States; OXA-48, Oxacillinase-48; NYC, New York city; LA, Los Angeles; KPC, K. pneumoniae carbapenemase; NDM, New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase; VIM, verona integron-encoded metallo-β-lactamase.

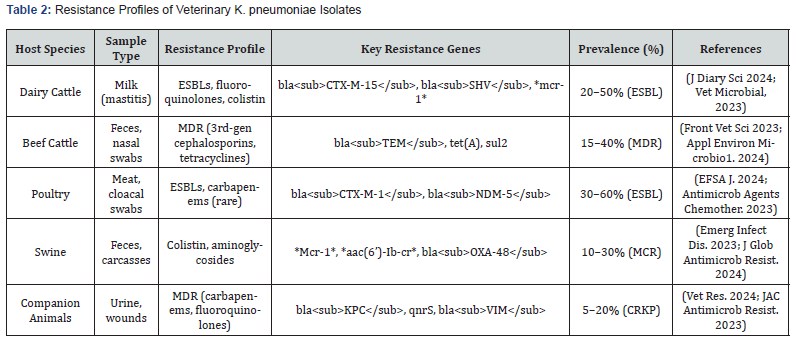

Abbreviations: ESBL, extended-spectrum beta-lactamases; MDR, multidrug-resistant; blaCTX-M-1, β-lactamase, cefotaximase- Munich group 1; blaNDM-5, β-lactamase, New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase-5 variant; mcr-1, mobilized colistin resistance gene 1; aac(6’)-Ib-cr, aminoglycoside acetyltransferase variant; blaOXA-48, beta-lactamase oxacillinase-48 gene; blaKPC; betalactamase, K. pneumoniae carbapenemase, qnrS, quinolone resistance protein S; blaVIM, beta-lactamase, Verona integron-encoded metallo-beta-lactamase; MCR, mobilized colistin resistance; CRKP, carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae.

Habitat and Transmission of Klebsiella pneumoniae

Klebsiella pneumoniae naturally inhabits the gastrointestinal and upper respiratory tracts of both humans and animals and is also commonly found in the environment [14]. Multiple transmission routes have been identified. In humans, person-toperson spread-particularly via the hands of healthcare workersis a major source of transmission [15]. In animals, transmission occurs through fecal–oral routes, contaminated surfaces, direct contact, and farm equipment such as milking machines and drinking water systems [16].

Antibiotic Resistance and Mechanisms

The acquisition of antimicrobial resistance (AR) determinants by pathogenic K. pneumoniae leads to resistance against multiple antibiotics, resulting in prolonged hospitalization and increased risk of healthcare-associated infections [17]. Resistance mechanisms include enzymatic drug inactivation, reduced membrane permeability, and modification of antimicrobial target sites.

Clinical Importance in Humans and Animals

K. pneumoniae causes a range of infections in humans and various animal species. In bovines, it is particularly associated with pneumonia, mastitis, and skin infections [18–22]. Immunocompromised hosts-both human and animal-are at higher risk of severe infection. Despite its clinical significance, limited information is available regarding the impact of K. pneumoniae on cattle welfare, productivity, epidemiology, and resistance development in non-human isolates. K. pneumoniae also contributes to neonatal sepsis [23]. Environmental factors, including increased rainfall and damp bedding, are associated with a higher prevalence of Klebsiella mastitis [24]. The bacterium is frequently isolated from milking machines, wash water, and farm drinking water, highlighting its diverse reservoirs and transmission points [21, 25].

Klebsiella Mastitis: Epidemiology and Impact

Diagnosing the causative agent of bovine mastitis can be challenging. Literature consistently reports Klebsiella spp., Escherichia coli, followed by Enterobacter and Serratia species, as the most frequently isolated Gram-negative pathogens in bovine clinical mastitis [26,27]. The reported incidence ratio of Klebsiella to E. coli mastitis ranges from 1:10 to 1:1 [28, 29]. K. pneumoniae can be highly infectious. Entry typically occurs through the teat canal, allowing the bacteria to proliferate in the udder, causing inflammation and milk loss. Its survival within the mammary gland is promoted by availability of nutrients and its ability to evade host immune defenses. The risk of infection is highest during the dry period due to easier bacterial access to the teat canal, poor hygiene, and bacterial colonization of the teat skin. In the periparturient period, elevated cortisol levels may suppress immune responses, increasing susceptibility. Severe coliform mastitis caused by Klebsiella can compromise the blood–milk barrier, leading to bacteremia and septicemia [27].

Public Health Significance and Need for Further Research

Antimicrobial-resistant strains of K. pneumoniae, especially extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL) and carbapenemase producers are identified by the World Health Organization as critical priority pathogens [30]. Losses caused by Klebsiella mastitis surpass those associated with E. coli mastitis in terms of milk production and animal survival [31]. Additionally, Klebsiella infections are often less responsive to treatment and tend to persist longer. Given these concerns, further research into virulence factors, AR mechanisms, plasmids, integrons, and gene cassettes involved in resistance transmission is urgently needed. This review aims to highlight the prevalence of K. pneumoniaeassociated mastitis, the epidemiology of Klebsiella infection in dairy animals, and the genetic determinants contributing to antimicrobial resistance [32].

Disease Course and Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of mastitis caused by K. pneumoniae and intra-mammary inflammation has not yet been adequately reported. The point source of infection includes bedding materials, manure, soil, and other organic cow-related environmental factors, such as sawdust and wood bedding materials. During the transition period of animals from nursing to weaning, the incidence of infection is significant. The teat canal serves as the entry point for bacteria. Once within the mammary gland, bacteria must utilize the available nutrients in the breast discharge while evading the host’s defensive system. Coliform mastitis is frequently diagnosed based on clinical signs, coliform organism culture from milk, and a high somatic cell count [33]. However, in the acute instance, the milk sample may be negative because neutrophils have removed the organisms. At least four components capsule, lipopolysaccharide, fimbriae, and siderophore have been identified as crucial for virulence despite heterogeneity among the strains [34]. K. pneumoniae attaches to the host cell surface thanks to the cell wall receptor. Bacteria alter their surface so that polymorph nuclear leukocytes and macrophages cannot phagocytize them. This ability renders the host cell non-phagocytic and mediates its safe entry to the host cell [35]. Then, capsular polysaccharide helps in the second invasion of Klebsiella. In addition, the capsule also mediates its non-phagocytic entry to the host cell. Further, the capsule also acts as a barrier to protect K. pneumoniae from host phagocytic activity. Endotoxin production by K. pneumoniae also contributes to its pathogenicity. However, its production is not dependent on factors that determine other virulent factors of K. pneumoniae. All these factors contribute relatively to the virulence of K. pneumoniae in vivo, making it difficult to determine their individual contributions, as they all contribute to virulence [30,32].

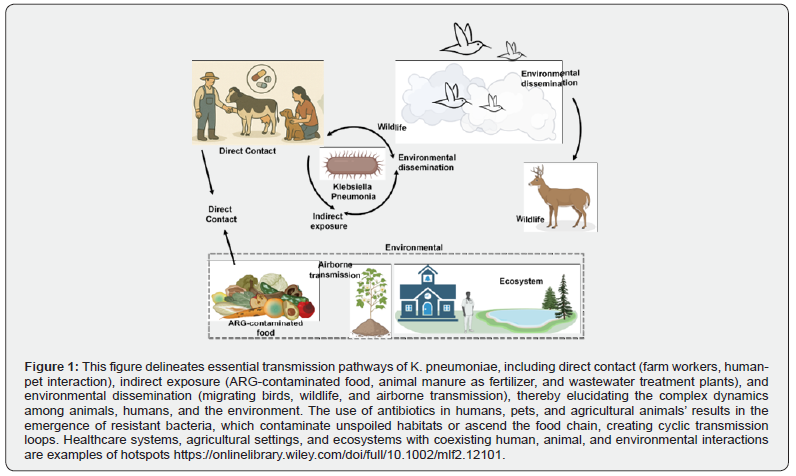

Animal and human transmission of K. pneumoniae

K. pneumoniae is a zoonotic pathogen that causes septicemic, pneumonic, and urinary tract infections in hospitals. Pathogenic K. pneumoniae strains with a hypermucoviscosity (HMV) phenotype have recently been linked to multisystem abs cessation in both humans and nonhuman primates. Although K. pneumoniae is a well-known zoonotic agent, general information, including effective diagnostic tools and therapies for nonhuman primates, is lacking [31]. Similar molecular types and behaviors across K. pneumoniae strains from various sources, including humans and animals, suggest that these strains may be transmitted between humans and animals, as shown in the Figure 1. To prevent the spread of K. pneumoniae between humans and animals, cautious antibiotic administration is required in both human clinical treatment and animal production [33,35].

ESBL and Carbapenemase-producing K. pneumoniae

ESBL producers can efficiently hydrolyze third generation cephalosporins, making them difficult to treat and resulting in severe damage [36]. In 1983, isolates of multi-drug-resistant ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae encoding blaSHV and blaTEM were first described in Europe [3738]. A short while later, K. pneumoniae reported another plasmid-mediated ESBL variation blaTEM-3 [39]. This was followed by several reports describing MDR K. pneumoniae from different parts of the world, including the US and South America [40,41]. Since the emergence of ESBLs in K. pneumoniae, this pathogen has become the primary source of ESBL dissemination. The recent discovery of MDR pathogenic K. pneumoniae that encodes ESBL/AmpC in broiler chickens, soil, boots, slurry surfaces, and ambient air in the United States indicates its persistent and rapid spread [42]. In addition, genes that produce beta-lactamase enzymes that are partially inhibited by clavulanic acid and tazobactam were discovered [43]. Over the last three decades, ESBL-producing Klebsiella has become a global epidemic in many countries. In conclusion, a literature study reveals that ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae has been reported from most parts of the world, indicating its international presence and ability to disseminate worldwide [44].

The endemic increase in K. pneumoniae-producing ESBL enzymes, which exhibit reduced or no response to many essential and effective antibiotics, has led to a significant increase in the use of carbapenem drugs. The development of plasmidmediated carbapenemases is a result of the widespread usage of carbapenem medicines. Carbapenem drugs are considered the last resort of antibacterials that can eradicate ESBL-producing pathogens. Imipenem was the first carbapenem to be used against Klebsiella infections in 1983, and the first carbapenem-resistant strain was reported only two years after its use [45,46]. A decade later, the extensive use of carbapenem drugs, K. pneumoniae carbapenemase (KPC), was described in the United State (US) [47]. Clinicians face a significant therapeutic challenge since KPC is well known for its resistance to all varieties of β-lactams and β-lactamase inhibitors [48].

Genetic Elements Responsible for Uptake and Dissemination of AR

Generally, Enterobacteriaceae, including K. pneumoniae, have adopted an array of mechanisms for the uptake and dissemination of drug resistance elements. This includes but is not limited to plasmids encoding drug resistance elements, uptake of gene cassettes, production of enzymes and other metabolites, and efflux of active drug molecules, etc. [17,49]. A successful bacterial strain should behave as an incredibly efficient vector for the spread of antibiotic resistance traits in the event of antibiotic resistance. This can be accomplished if the organism is capable of vertical AR element transmission and serves as a direct donor of horizontally mobile genetic elements, such as plasmids and transposons (Woodford et al., 2011). K. pneumoniae possesses a flexible genome that can mutate in response to stress. This mutation helps them to maintain their genome integrity and maintain their natural resistance. K. pneumoniae isolates have frequently been shown to contain transposons, plasmids, and integrons that carry genes for antibiotic resistance [50-52].

Epidemiology of K. pneumoniae causing mastitis in dairy animals

Clinical mastitis–causing pathogens vary geographically. Historically, Gram-positive organisms such as Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus agalactiae were the major agents in Europe and other regions; however, strict hygiene protocols have significantly reduced their prevalence. In contrast, systematic yearly epidemiological data on Klebsiella mastitis remain limited, with most available information coming from isolated studies worldwide [27, 53].

In the United States, approximately 40% of mastitis cases are attributed to Gram-negative bacteria [54], predominantly coliforms such as E. coli and K. pneumoniae. Klebsiella mastitis is more frequently observed in cattle kept indoors during winter, whereas its occurrence in pasture-grazed animals is uncommon [55]. A recent study from Japan reported the blaCTX-M-2 gene in most ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae isolated from mastitic milk, consistent with earlier findings of MDR Klebsiella in livestock, food sources, and the environment [56]. In several outbreaks, Klebsiella has shown remarkable pathogenicity. For example, in the US in 2006, the susceptibility of dairy herds to K. pneumoniae increased sharply, and 59% of 410 milk samples from cows with clinical mastitis yielded K. pneumoniae [57]. High prevalence has also been reported in Bangladesh, where Klebsiella species were detected in 62.5% of clinical mastitis cases [58]. In Southwest China, isolates exhibited high resistance to commonly used antibiotics, showing greater resistance patterns than isolates from Iran [59, 60]. In India, Klebsiella mastitis incidence has ranged from 20.16% to 24% [60, 61].

Epidemiological Status in Pakistan

Mastitis is considered the most economically important disease of cattle in Pakistan, with incidence rates varying from 15% to 80% [62–64]. Despite this, country-wide data on pathogen-specific prevalence remain fragmented. A recent 2018– 2019 study reported 20% mastitis in cattle, with 8% attributed to K. pneumoniae [65]. In buffaloes from Sindh, K. pneumoniae accounted for 11% of mastitis cases [66]. In goats from Kohat (Khyber Pakhtunkhwa), prevalence was 3.6% for Klebsiella and 11.5% for E. coli.

A four-year investigation in Peshawar (2010–2013) involving 2,791 milk samples showed 81% positivity for mastitis, with 6% caused by Klebsiella [67]. However, recent unpublished data generated from over 10,000 milk samples across 11 districts of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa suggest that the true incidence of Klebsiella mastitis may be significantly higher than previously reported. Limited surveillance, high diagnostic costs, and lack of technical capacity may have contributed to underreporting. Continuous monitoring and identification of pathogens are critical for mastitis control. Evidence indicates a shift in mastitis-causing agents, highlighting the need for surveillance programs to prevent the spread of contagious Klebsiella infections in dairy herds.

One Health Surveillance and Cross-Species Transmission Risks

A One Health approach emphasizes coordinated monitoring across human, animal, and environmental sectors. Integrated surveillance programs can track antimicrobial resistance (AMR) trends in animal reservoirs and evaluate their potential transmission risks to humans. Comprehensive strain characterization is needed to understand the diversity and epidemiological links between K. pneumoniae in livestock and human populations [68].

Clinical Impact and Economic Burden of K. pneumoniae Mastitis

K. pneumoniae mastitis poses serious clinical and economic challenges in dairy production. Clinically, affected animals develop severe udder inflammation, reduced milk yield, fever, and abnormal milk containing clots and flakes. The condition can lead to death or necessitate culling. Compared with E. coli mastitis, K. pneumoniae infections are generally more severe and associated with higher culling and mortality rates [69]. Economically, the estimated total failure cost of bovine mastitis is approximately $147 per cow per year, with milk production losses and culling accounting for 11–18% of the gross margin per cow. Damage to mammary tissue accounts for 70% of total losses. Treatment is complicated by poor antibiotic response, and costs are often driven by milk discard due to antibiotic residues.

Alternative therapies, including bacteriophage-based approaches, are being explored to reduce inflammation and bacterial load [1]. Vaccines have shown variable success, and further research is needed to develop effective immunization strategies against K. pneumoniae mastitis [70].

Future Direction and Research Gap

AMR studies should concentrate on examining the molecular mechanisms of AMR and developing novel therapeutic strategies [71]. Vaccine development should explore potential candidates to prevent K. pneumoniae infections. Extensive genomic studies are required to understand strain diversity and transmission dynamics [72]. Although K. pneumoniae is known to cause mastitis, significant gaps remain in understanding, including unclear AMR mechanisms, limited livestock surveillance, and virulent factors associated with K. pneumoniae strains. In the future, researchers should concentrate on One Health surveillance and genomic analyses to understand strain diversity, resistance, and host interactions.

Conclusion

ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae poses a major threat to dairy herds due to its severe disease impact, treatment difficulty, and ability to spread antimicrobial resistance. Preventive measuresespecially during wet and winter seasons-should focus on strict hygiene, proper milking equipment sanitation, prudent antibiotic use, and improved bedding and moisture control. At a larger scale, a coordinated One Health approach with continuous surveillance and molecular monitoring is essential to detect resistant strains early and prevent their spread across animals, humans, and the environment.

Acknowledgement

We gratefully acknowledge the financial support provided by the Higher Education Commission (HEC) of Pakistan through the NRPU project (No. 8633), awarded to the principal investigator, Dr. Sadeeq Ur Rahman. The authors also express their sincere appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Khalid University for supporting this work through the Large Research Group Program, grant number R.G.P.02/709/46.

References

- Navon-Venezia S, Kondratyeva K, Carattoli A (2017) Klebsiella pneumoniae: a major worldwide source and shuttle for antibiotic resistance. FEMS Microbiol Rev 41:252-75.

- Zowawi HM (2016) Antimicrobial resistance in Saudi Arabia: an urgent call for an immediate action. Saudi Med J 37:935-940.

- Lee CR, Lee JH, Park KS, Jeon JH, Kim YB, Cha CJ, et al. (2017) Antimicrobial resistance of hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae: epidemiology, hypervirulence-associated determinants, and resistance mechanisms. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 7: 483.

- Ur Rahman S, Mohsin M (2019) The under reported issue of antibiotic resistance in food-producing animals in Pakistan. Pak Vet J. 39:1-16.

- Ur Rahman S, Hussain MA, Murtaza A, Sarwar MM, Ali T, Jamal M, et al. (2019) How ESBL- and carbapenemase-producing genes are mobilized-analysis of Escherichia coli isolates recovered from poultry retail meat in District Mardan, KPK, Pakistan. 2019 16th International Bhurban Conference on Applied Sciences and Technology (IBCAST). IEEE, Piscataway, NJ 16:191-96.

- Ur Rahman S, Ali T, Muhammad N, Umer T, Ahmad S, Ayaz S, et al. (2018) Characterization and mechanism of dissemination of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli in food-producing animals in Pakistan and China. 2018 15th International Bhurban Conference on Applied Sciences and Technology (IBCAST). IEEE, Piscataway, NJ 15.

- Tareen AM, Ullah K, Asmat TM, Samad A, Iqbal A, Mustafa MZ, et al. (2019) Incidence of diarrheagenic Escherichia coli pathotypes in children suffering from diarrhea in tertiary care hospitals, Quetta, Pakistan. Pak J Zool 51:2015-21.

- Khan SH, Jahan S, Ahmad I, Ur Rahman S, Ur Rehman T (2019) Incidence of blaIMP and blaVIM genes among carbapenemase-producing Escherichia coli in Lahore, Pakistan. Pak J Zool 51:1959-65.

- Khan S, Taj R, Rehman N, Ullah A, Khan I, Ur Rahman S (2020) Incidence and antibiogram of β-lactamase-producing Citrobacter freundii recovered from clinical isolates in Peshawar, Pakistan. Pak J Zool 52:1877-83.

- Adnan M, Khan H, Kashif J, Ahmad S, Gohar A, Ali A, et al. (2017) Clonal expansion of sulfonamide-resistant Escherichia coli isolates recovered from diarrheic calves. Pak Vet J 37:230-32.

- Aqib AI, Nighat S, Ahmed R, Sana S, Jamal MA, Kulyar MF, et al. (2019) Drug susceptibility profile of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from mastitic milk of goats and risk factors associated with goat mastitis in Pakistan. Pak J Zool 51:307-15.

- Rahman SU, Ahmad S, Khan I (2019) Incidence of ESBL-producing Escherichia coli in poultry farm environment and retail poultry meat. Pak Vet J 39:116-20.

- Younas M, Ur Rahman S, Shams S, Salman MM, Khan I (2019) Multidrug resistant carbapenemase-producing Escherichia coli from chicken meat reveals diversity and co-existence of carbapenemase encoding genes. Pak Vet J 39:241-245.

- Burke RL, West MW, Erwin-Cohen R, Selby EB, Fisher DE, Twenhafel NA (2010) Alterations in cytokines and effects of dexamethasone immunosuppression during subclinical infections of invasive Klebsiella pneumoniae with hypermucoviscosity phenotype in rhesus (Macaca mulatta) and cynomolgus (Macaca fascicularis) macaques. Comp Med 60:62-70.

- Jarvis WR, Munn VP, Highsmith AK, Culver DH, Hughes JM (1985) The epidemiology of nosocomial infections caused by Klebsiella pneumoniae. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 6:68-74.

- Snitkin ES, Zelazny AM, Thomas PJ, Stock F (2012) National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Pathogen Detection Project, Henderson DK, et al.: Tracking a hospital outbreak of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae with whole-genome sequencing. Sci Transl Med. 4:148ra116.

- Pomakova D, Hsiao C, Beanan J, Olson R, MacDonald U, Keynan Y, et al. (2012) Clinical and phenotypic differences between classic and hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae: an emerging and under-recognized pathogenic variant. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 31:981-89.

- Locatelli C, Scaccabarozzi L, Pisoni G, Moroni P (2010) CTX-M1 ESBL-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae subsp. pneumoniae isolated from cases of bovine mastitis. J Clin Microbiol 2010 48:3822-3823.

- Ribeiro M, Motta R, Paes A, Allendorf S, Salerno T, Siqueira A, et al. (2008) Peracute bovine mastitis caused by Klebsiella pneumoniae. Pesqui Vet Bras 28:419-23.

- Cheng J, Zhang J, Han B, Barkema HW, Cobo ER, Kastelic JP, et al. (2020) Klebsiella pneumoniae isolated from bovine mastitis is cytopathogenic for bovine mammary epithelial cells. J Dairy Sci. 2020, 103:3493-504.

- Munoz MA, Welcome FL, Schukken YH, Zadoks RN (2007) Molecular epidemiology of two Klebsiella pneumoniae mastitis outbreaks on a dairy farm in New York State. J Clin Microbiol 45(12):3964-3971

- Paulin-Curlee G, Singer R, Sreevatsan S, Isaacson R, Reneau J, Foster D, et al. (2007) Genetic diversity of mastitis-associated Klebsiella pneumoniae in dairy cows. J Dairy Sci 90(8):3681-3689.

- Camacho-Gonzalez A, Spearman PW, Stoll BJ (2013) Neonatal infectious diseases: evaluation of neonatal sepsis. Pediatr Clin North Am 60(2):367-389.

- Thomas C, Jasper D, Rollins M, Bushnell R, Carroll E (1983) Enterobacteriaceae bedding populations, rainfall and mastitis on a California dairy. Prev Vet Med 1(3):227-242.

- Nonnecke B, Newbould FJ (1984) Biochemical and serologic characterization of Klebsiella strains from bovine mastitis and the environment of the dairy cow. Am J Vet Res 45(11):2451-2454.

- Brisse S, van Duijkeren E (2005) Identification and antimicrobial susceptibility of 100 Klebsiella animal clinical isolates. Vet Microbiol 105(3-4):307-312.

- Hogan J, Smith KL (2003) Coliform mastitis. Vet Res 34(5):507-519.

- Roberson J, Warnick L, Moore GJ (2004) Mild to moderate clinical mastitis: efficacy of intramammary amoxicillin, frequent milk-out, a combined intramammary amoxicillin, and frequent milk-out treatment versus no treatment. J Dairy Sci 87(3):583-592.

- Barkema H, Schukken Y, Lam T, Beiboer M, Wilmink H, Benedictus G, et al. (1998) Incidence of clinical mastitis in dairy herds grouped in three categories by bulk milk somatic cell counts. J Dairy Sci 81(2):411-419.

- Podschun R, Ullmann U (19989) Klebsiella spp. as nosocomial pathogens: epidemiology, taxonomy, typing methods, and pathogenicity factors. Clin Microbiol Rev 11(4):589-603.

- Muñoz M, Ahlström C, Rauch B, Zadoks RJ (2006) Fecal shedding of Klebsiella pneumoniae by dairy cows. J Dairy Sci 89(9):3425-3430.

- Cobirka M, Tancin V, Slama P (2020) Epidemiology and classification of mastitis. Animals (Basel). 2020, 10(12):2212.

- Schukken Y, Chuff M, Moroni P, Gurjar A, Santisteban C, Welcome F, et al. (2012) The “other” gram-negative bacteria in mastitis: Klebsiella, Serratia, and more. Vet Clin North Am Food Anim Pract 28(2):239-256.

- Ma LC, Fang CT, Lee CZ, Shun CT, Wang JT (2005) Genomic heterogeneity in Klebsiella pneumoniae strains is associated with primary pyogenic liver abscess and metastatic infection. J Infect Dis 192(1):117-128.

- Davis GS, Price LB (2016) Recent research examining links among Klebsiella pneumoniae from food, food animals, and human extraintestinal infections. Curr Environ Health Rep 3(2):128-135.

- Jacoby GA, Sutton L (1991) Properties of plasmids responsible for production of extended-spectrum beta-lactamases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 35(1).

- Knothe H, Shah P, Krcméry V, Antal M, Mitsuhashi S (1983) Transferable resistance to cefotaxime, cefoxitin, cefamandole and cefuroxime in clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae and Serratia marcescens. Infection 11(6):315-317.

- Kliebe C, Nies B, Meyer JF, Tolxdorff-Neutzling RM, Wiedemann B (1985) Evolution of plasmid-coded resistance to broad-spectrum cephalosporins. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 28(2):302-307.

- Sirot D, Sirot J, Labia R, Morand A, Courvalin P, Darfeuille-Michaud A, et al. (1987) Transferable resistance to third-generation cephalosporins in clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae: identification of CTX-1, a novel β-lactamase. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 31(1):103-109.

- Kaiser RM, Castanheira M, Jones RN, Tenover F, Lynfield R (2013) Trends in Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase-positive K. pneumoniae in US hospitals: report from the 2007–2009 SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 76(3):356-360.

- Villegas MV, Lolans K, Correa A, Suarez CJ, Lopez JA, Vallejo M, et al. (2006) First detection of the plasmid-mediated class A carbapenemase KPC-2 in clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae from South America. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 50(8):2880-2882.

- Long SW, Olsen RJ, Eagar TN, Beres SB, Zhao P, Davis JJ, et al. (2017) Population genomic analysis of 1,777 extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates, Houston, Texas: unexpected abundance of clonal group 307. mBio 8(3): e00489-17.

- Bush K, Jacoby GA (2010) Updated functional classification of β-lactamases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 54(3):969-976.

- Laube H, Friese A, von Salviati C, Guerra B, Rösler U (2014) Transmission of ESBL/AmpC-producing Escherichia coli from broiler chicken farms to surrounding areas. Vet Microbiol 172(3-4):519-527.

- Baumgartner JD, Glauser MP (1983) Comparative study of imipenem in severe infections. J Antimicrob Chemother 12(Suppl D):141-148.

- Knothe H, Antal M, Krcméry V (1987) Imipenem and ceftazidime resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Antimicrob Chemother 19(1):136-138.

- Yigit H, Queenan AM, Anderson GJ, Domenech-Sanchez A, Biddle JW, Steward CD, et al. (2001) Novel carbapenem-hydrolyzing β-lactamase, KPC-1, from a carbapenem-resistant strain of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 45(4):1151-1161.

- Bush K, Jacoby GA (2010) Updated functional classification of β-lactamases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 54(3):969-976.

- Whitehouse CA, Keirstead N, Taylor J, Reinhardt JL, Beierschmitt A (2010) Prevalence of hypermucoid Klebsiella pneumoniae among wild-caught and captive vervet monkeys (Chlorocebus aethiops sabaeus) on the island of St. Kitts. J Wildl Dis 46(3):971-976.

- Yan JJ, Ko WC, Wu JJ (2001) Identification of a plasmid encoding SHV-12, TEM-1, and a variant of IMP-2 metallo-β-lactamase, IMP-8, from a clinical isolate of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 45: 2368-2371.

- Roy Chowdhury P, Ingold A, Vanegas N, Martínez E, Merlino J, Merkier AK, et al. (2011) Dissemination of multiple drug resistance genes by class 1 integrons in Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates from four countries: a comparative study. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 55:3140-3149.

- Chen LF, Anderson DJ, Paterson DL (2012) Overview of the epidemiology and the threat of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemases (KPC) resistance. Drug Resist Updat 15:133-141.

- Wenz JR, Barrington GM, Garry FB, McSweeney KD, Dinsmore RP, Goodell G, et al. (2001) Bacteremia associated with naturally occurring acute coliform mastitis in dairy cows. J Am Vet Med Assoc 219:976-981.

- Erskine R, Tyler J, Riddell M Jr, Wilson RJ (1991) Theory, use, and realities of efficacy and food safety of antimicrobial treatment of acute coliform mastitis. J Am Vet Med Assoc 198:980-984.

- Ross R, Zimmerman B, Wagner W, Cox DJ (1975) A field study of coliform mastitis in sows. J Am Vet Med Assoc 167:231-235.

- Wareth G, Neubauer H (2021) The animal-foods-environment interface of Klebsiella pneumoniae in Germany: an observational study on pathogenicity, resistance development and the current situation. Vet Res, 52:16.

- Munoz MA, Welcome FL, Schukken YH, Zadoks RN (2007) Molecular epidemiology of two Klebsiella pneumoniae mastitis outbreaks on a dairy farm in New York State. J Clin Microbiol 45:3964-3971.

- Salauddin M, Akter MR, Hossain MK, Rahman MM (2019) Isolation of multidrug-resistant Klebsiella sp. from bovine mastitis samples in Rangpur, Bangladesh. J Adv Vet Anim Res 6:362-365.

- Cheng F, Li Z, Lan S, Liu W, Li X, Zhou Z, et al. (2017) Characterization of Klebsiella pneumoniae associated with cattle infections in southwest China using multilocus sequence typing (MLST), antibiotic resistance and virulence-associated gene profile analysis. Braz J Microbiol 49:93-100.

- Singh K, Chandra M, Kaur G, Narang D, Gupta DK (2018) Prevalence and antibiotic resistance pattern among the mastitis-causing microorganisms. Open J Vet Med 8:54-64.

- Bhatt VD, Patel MS, Joshi CG, Kunjadia AJ (2011) Identification and antibiogram of microbes associated with bovine mastitis. Arch Biol Sci 63:163-169.

- Ali M, Ahmad M, Muhammad K, Anjum AJ (2011) Prevalence of subclinical mastitis in dairy buffaloes of Punjab, Pakistan. J Anim Plant Sci 21:477-480.

- Bilal M, Iqbal M, Muhammad G, Avais M, Sajid MJ (2004) Factors affecting the prevalence of clinical mastitis in buffaloes around Faisalabad district, Pakistan. Int J Agric Biol 6:185-187.

- Sharif A, Muhammad G (2009) Mastitis control in dairy animals. Pak Vet J 29:145-148.

- Ali T, Kamran K, Raziq A, Wazir I, Ullah R, Shah P, et al. (2021) Prevalence of mastitis pathogens and antimicrobial susceptibility of isolates from cattle and buffaloes in north-west of Pakistan. Front Vet Sci 8:1148.

- Memon M, Mirbahar K, Memon M, Akhter N, Soomro S, Dewani P (1999) A study on the etiology of subclinical mastitis in buffaloes. Pak J Agric Agril Eng Vet Sci.

- Khan MA, Shafee M, Akbar A, Ali A, Shoaib M, Ashraf F, et al. (2017) Occurrence of mastitis and associated pathogens with antibiogram in animal population of Peshawar, Pakistan. Pak J Vet Med 47(1):103.

- Barani M, Fathizadeh H, Arkaban H, Kalantar-Neyestanaki D, Akbarizadeh MR, Jalil AT, et al. (2022) Recent advances in nanotechnology for the management of Klebsiella pneumoniae-related infections. Biosensors (Basel) 12(12):1155.

- Aruhomukama D, Nakabuye H (2023) Investigating the evolution and predicting the future outlook of antimicrobial resistance in Sub-Saharan Africa using phenotypic data for Klebsiella pneumoniae: a 12-year analysis. BMC Microbiol 23(1):214.

- Cabrera A, Mason E, Mullins LP, Sadarangani M (2025) Antimicrobial resistance and vaccines in Enterobacteriaceae including extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae. NPJ Antimicrob Resist 3(1):1-14.

- Mohammadi M, Saffari M, Siadat SD (2023) Phage therapy of antibiotic-resistant strains of Klebsiella pneumoniae: opportunities and challenges from the past to the future. Folia Microbiol (Praha) 68(3):357-368.

- de Oliveira Júnior NG, Franco OL (2020) Promising strategies for future treatment of Klebsiella pneumoniae biofilms. Future Microbiol 15(1):63-79.