Abstract

The purpose of this report is to describe the macroscopic and microscopic lesions of the digestive system in a case of emphysematous necroulcerative abomasitis in 13 growing calves caused by Sarcina spp. During the night of October 13, calves out of a total of 80, aged from 9 to 16 days, died suddenly, without having been sick or treated before. At autopsy, the mucosal folds of the abomasum were severely edematous with necrosis and bleeding ulcers, covered with whitish fibrinous exudate. The abomasal folds had an emphysematous to bullous appearance due to the accumulation of gas in the mucosa and submucosal. Microscopically, numerous bacteria were observed in the villi, grouped 4 to 20 in cuboidal packages - Sarcina spp., mixed with fibrin, desquamated necrobiotic epithelial cells, macrophages and karyorectic neutrophils. In conclusion, the described pathoanatomical and pathohistological changes in the abomasum and the remaining intestinal segments in our case could be beneficial for the pathomorphological diagnosis of abomasitis in calves caused by bacteria of the genus Sarcina.

Keywords:calves; emphysematous abomasitis; histopathology; sarcina spp

Introduction

Abomasal diseases affect calves, lambs, and kids under 2 months of age. Abomasitis is also described in the veterinary literature as abomasal tympania, abomasal bloat and braxite-like disease [1]. According to Mills et al. [2], the disease in calves has a multifactorial etiology, such as feeding large amounts of milk through an esophageal tube, cold milk, carbohydrate-rich milk replacer, poor equipment hygiene, and others. The main bacterial pathogens causing abomasitis in ruminants are Clostridium perfringens type A, Sarcina spp., Escherichia coli, Lactobacillus spp., and Campylobacter spp. [3] Bacteria of the genus Sarcina have been implicated as common causes of emphysematous abomasitis. The disease occurs during the first few weeks after birth in young ruminants such as calves, lambs and kids [4]. John Goodsir first observed Sarcina sрp. in 1842 in the gastric contents of a human with signs of vomiting, stomach pain and bloating [5]. Clinical presentation includes sudden death, lethargy, colic, diarrhea and abdominal distension. Macroscopic and microscopic lesions observed during necropsy in calves were a distended abomasum filled with a large amount of reddish-brown foul-smelling fluid and acute emphysematous necrotizing hemorrhagic inflammation of the mucosa. Abomasal ulcers were rarely observed [6]. According to [7], Sarcina-like bacteria frequently cause emphysematous abomasitis in suckling calves, through a mechanism of gas accumulation in the mucosa and submucosa of the abomasum. The aim of the presented clinical case of emphysematous necroulcerative abomasitis in calves is to emphasize the macroscopic and microscopic changes in the digestive system caused by Sarcina spp., and their use in gastrointestinal pathology.

Materials and Methods

The present report presents a spontaneous case of necroulcerative emphysematous abomasitis in growing calves, which occurred with 15% morbidity and 100% mortality. Diagnosed on the basis of pathoanatomical and histopathological studies. Оn a private dairy cattle farm in Northern Bulgaria. The farm consisted of 350 Holstein-Friesian dairy cows, 57 calves between 45 and 120 days old, and 80 newborn and growing calves aged from 24 hours after birth to 45 days old. All cows were dewormed and vaccinated preventively against infectious diseases - mucosal disease - viral diarrhea, bovine herpes virus, respiratory disease complex, rotavirus, coronaviruses as well as Escherichia coli during pregnancy. At birth, the calves were placed in separate disinfected boxes. After that, they were immediately probed and colostrum (stored in the refrigerator) was administered to them for 3 days, 3-4 times 2 liters per calf. After the third day, the calves were switched to milk replacer, starter pelleted feed and corn, without the addition of probiotics. All calves were vaccinated against clostridial infections, and treated against cryptosporidiosis and coccidiosis. During the night of October 13, calves aged 9 to 16 days died suddenly, without having been sick or treated before. The owner said he found them in the morning, having eaten normally the previous evening without any signs of illness. The bodies of the dead calves were severely swollen. A veterinarian was called to the farm to examine the animals. No animals with clinical signs of fever were found. All thirteen calf carcasses were submitted for autopsy and subsequent diagnostic tests personally by the farm owner. After the autopsy of the calves, tissue samples of 1 cm x 1 cm in size were obtained for histopathological examination from: ileum, duodenum, jejunum with mesenteric lymph nodes, ileum, cecum, colon and rectum. The materials for histopathological examination were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for 48–72 hours and embedded in paraffin. From the obtained paraffin blocks, 4 μm thick sections were prepared using a Leica RM 2235 microtome and stained conventionally with hematoxylin-eosin (H/E). Using intestinal contents from autopsied calves for laboratory diagnosis of current enter pathogens causing neonatal diarrhea in ruminants. Antigenic quantitative ELISA (BIOX Diagnostics, easy digest, Belgium). Also, samples from parenchymal organs (lung, liver, spleen and kidney), blood from the heart and a ligated section of the small intestine were used for bacteriological studies.

Results and Discussion

Macroscopic findings

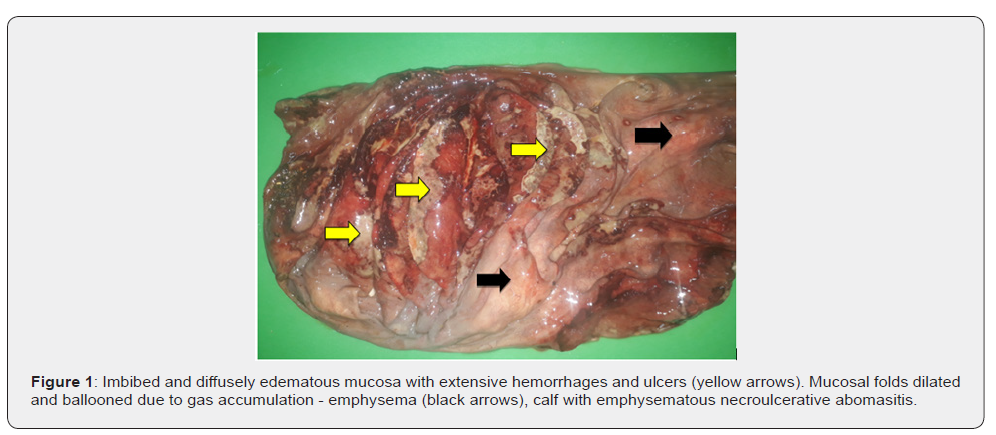

From the autopsy of 13 carcasses of suddenly deceased calves following the standard autopsy protocol for ruminants, the following pathoanatomical changes were recorded: pale conjunctive, bilateral catarrhal discharge from the nostrils, severely swollen carcass and enlarged abdomen crepitating on palpation, hemorrhagic-mucous staining in the perianal area, rectal prolapse and lack of rigor mortis. On examination of the abdominal cavity, the abomasum was repeatedly enlarged, crepitant on palpation with pinpoint hemorrhages on the serous in all 13 calves. In a section of the mucosa there were extensive hemorrhages, hyperemia and, in places, hemorrhagic imbibition. The mucosal folds were highly edematous, with multiple necrosis and extensive bleeding ulcers of irregular shape, some covered with whitish fibrinous exudate (Figure 1). In a transversal section of the abomasal wall, the folds had an emphysematous, in places even bullous appearance, due to the accumulation of gases in the mucosa and submucosa. In another of our Kalkanov [4] cases of emphysematous abomasitis in lambs, extensive hemorrhages, necrosis and bleeding ulcers on the mucosa of the colostrum were not observed. In a study by Kalkanov [8] on clostridial infection in calves, the lesions in the colostrum were expressed as a catarrhalhemorrhagic type, without ulcers and necrosis. Experts in the field such as Guarnieri et al. [6] have observed acute emphysematous necrotizing hemorrhagic inflammation, without ulcers, of the abomasum mucosa in calves. In the reticulum, omasum and rumen there were food masses mixed with brownish bloody contents. A team led by Tartaglia et al. [9] described a case of gastritis in a 69-year-old man caused by sarcinia. Diffuse hyperemia, erosions, and fibrin were observed in the gastric mucosa. The entire length of the small and large intestines was ballooned, and the mesenteric vessels were injected. The mesenteric lymph nodes did not react.

Microscopic findings

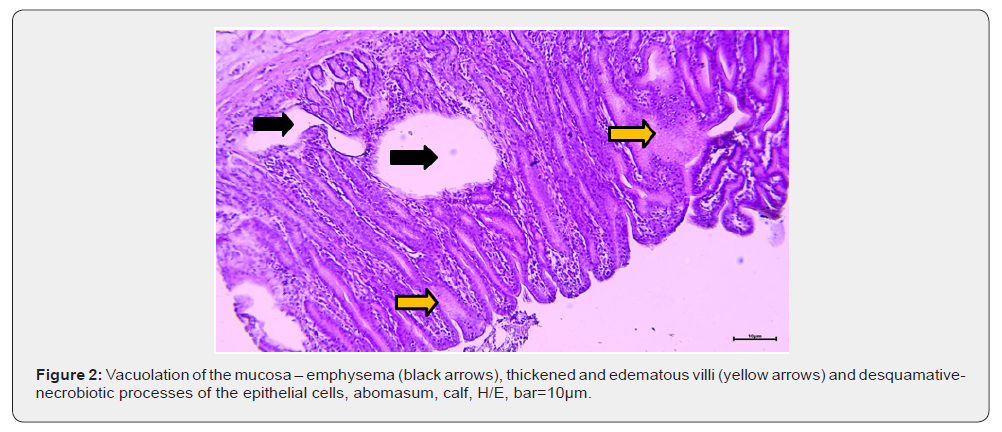

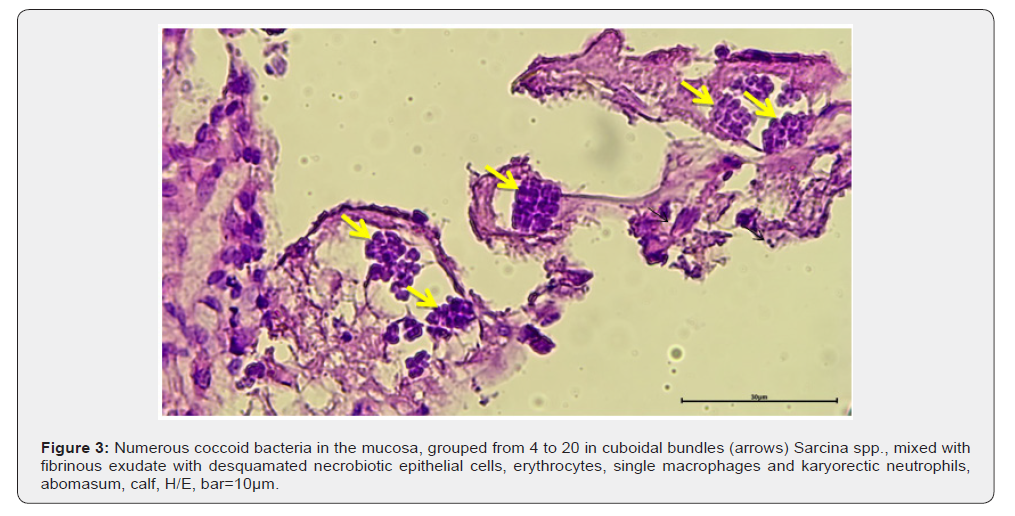

During the histopathological examinations in the rennet, the following microscopic changes were found: congestion, hemorrhages, areas of hyalinization and edema of the muscular layer. Fibrinous exudate mixed with air bubbles, fibrin, erythrocytes, macrophages, neutrophils and necrobiotic cells permeating the mucosa and submucosal. There was vacuolization of the mucosa – emphysema. The villi were severely thickened and edematous with desquamative-necrobiotic processes of the epithelial cells (Figure 2). Researchers such as Balaro et al. [10] have also observed hyalinization of the muscular layer of the rennet in clostridial abomasitis in kids. On the surface of the villi and within them, bacteria from 4 to 20 in number were observed, grouped in several cuboidal packages having a typical morphology of gram-positive cocci - Sarcina spp. Mixed with fibrin, desquamated necrobiotic epithelial cells, macrophages and karyorectic neutrophils (Figure3). Which prompted us to make a histopathological diagnosis - Sarcina spp. Degenerativenecrobiotic changes were present in the epithelium of the glands and hypersecretion. In contrast to us, [9] have found transmural bacterial columns of Sarcina spp. in the stomach. According to Perrault et al. [11], sarcins cause lymphocytic esophagitis in humans. These results are somewhat consistent and overlap with those of [4] in the case of emphysematous abomasitis in lambs. Western researchers describe [6] three main microlesions in calves: edema, hemorrhages, and emphysema in the abomasal mucosa. In contrast to us, others such as [12] report the presence of coagulative necrosis in the mucosa, bacterial colonies around the vessels and emphysema in the submucosal, neutrophils, bacterial emboli and fibrin thrombi in the vessels in fibrin necrotizing abomasitis in lambs. In the remaining examined segments of the gastrointestinal tract (duodenum, jejunum, ileum, cecum, colon and rectum), no desquamative processes affecting the villus epithelium were detected. Only edema was present in the submucosa. The results obtained from the laboratory antigen tests were negative for Clostridium perfringens, Cryptosporidium parvum, rotaviruses, coronaviruses and Escherichia coli. No pathogenic microorganisms were detected in the microbiological examination conducted to isolate and identify aerobic and anaerobic microbial pathogens. In conclusion, the pathoanatomical and pathohistological changes in the abomasum and the remaining intestinal segments described by us in the presented case of emphysematous necroulcerative abomasitis could be beneficial for the pathomorphological diagnosis of abomasitis in calves caused by bacteria of the genus Sarcina. The described histopathological lesions caused by Sarcina spp. Could also have significant value in the differential diagnosis of other rennet diseases, such as Clostridium perfringens type A, Escherichia coli., Lactobacillus spp., Campylobacter spp., and other viral infections in newborn and growing ruminants.

References

- Burgstaller J, Wittek T, Smith G (2017) Abomasal emptying in calves and its potential influence on gastrointestinal disease. J Dairy Sci 100: 17-35.

- Mills K, Johnson J, Jensen R (1990) Laboratory findings associated with abomasal ulcers/tympany in range calves. J Vet Diagn Invest 2: 208-212.

- Panciera R, Boileau M, Step D (2007) Tympany, acidosis, and mural emphysema of the stomach in calves: report of cases and experimental induction. J Vet Diagn Invest 19: 392-395.

- Kalkanov I (2025) Clinic morphological studies in a clinical case of emphysematous abomasitis in a lamb herd in Bulgaria. Eurasian J Vet Sci 41: 001-005.

- Marcelino L, Valentini Junior D, Schaefer P (2021) Sarcina ventriculi a rare pathogen. Autops Case Rep 11: 334-337.

- Guarnieri E, Fecteau G, Berman J (2020) Abomasitis in calves: A retrospective cohort study of 23 cases (2006-2016). J Vet Intern Med 34: 1018-1027.

- Schemm T, Nagaraja T, DeBey B (1999) Sarcina ventriculi as the potential cause of abomasal bloat. Kansas Agricultural Experiment Station Research Reports 387: 130-131.

- Kalkanov I (2024) Pathomorphological and etiological studies in a clinical case of necrohaemorrhagic enteritis in buffaloes. Traditional and modernity in veterinary medicine 9: 26-34.

- Tartaglia D, Coccolini F, Mazzoni A (2022) Sarcina Ventriculi infection: a rare but fearsome event. A Systematic Review of the Literature. International Journal of Infectious Diseases 115: 48-61.

- Balaro M, Gonçalves F, Lealet F (2022) Outbreak of abomasal bloat in goat kidsdue to Clostridium ventriculi and Clostridium perfringens type A. Braz. J Vet Pathol 15: 99-104.

- Perrault F, Echelard P, Baillargeon J (2021) Sarcina ventriculi in the esophagus: A case report and review of the Literature/Sarcina ventriculi dans l'aesophage: etude de cas et revue de la Literature. Canadian Journal of Pathology 13: 49-53.

- Estela P, Francisco A, Ricardo de Migue A (2024) Mannheimia haemolytica–associated fibrinonecrotizing abomasitis in lambs. Veterinary Pathology 3: 1-5.