Traditional Chinese Medicine Market in Hong Kong

Kin Long Cooby Cheung1, Eric Raymond Buckley2and Kenji Watanabe3*

1Faculty of Medicine, University of Hong Kong, China

2Department of Integrative Medicine and Palliative Care, Christus St. Vincent Regional Medical Center, USA

3Faculty of Environment and Information Studies, Keio University, Japan

Submission: September 26, 2017; Published: November 27, 2017

*Corresponding author: Kenji Watanabe, Faculty of Environment and Information Studies, Keio University, Kanagawa 252-0882, Japan, Tel: +81-466-49-3463; Fax: +81-466-49-3463; Email: watanabekenji@keio.jp

How to cite this article: Kin L C C, Eric R B, Kenji W. Traditional Chinese Medicine Market in Hong Kong. J Complement Med Alt Healthcare. 2017; 4(1):555630. DOI: 10.19080/JCMAH.2017.04.555630

Abstract

Since official supportive initiatives were launched in 1997 by the Hong Kong government, the traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) industry has grown into one of the main industries in the healthcare sector of Hong Kong. This essay aims to investigate and summarize the TCM development in Hong Kong in various aspects, from history, education of TCM practitioners, current TCM systems, human resources, law restrictions, market share, health insurance, harvest place of raw herbs to the price of concentrated Chinese medicine granules. It is concluded that the TCM industry in Hong Kong contiunes developing economically and clinically. With a similar background between Kampo and TCM, it is believed that both fields can join forces to make a fundamental contribution to modern medical industry.

Keywords: Traditional chinese medicine; Education; Herbal policy, Market, Herbal procurement, Hong kong, Japan

Introduction

Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) originates in ancient China with a 5000-year history. Rooted in ancient Eastern philosophies such as Taoism, TCM focuses on a holistic view between humans and nature. Through the observations of universal principles within nature, TCM inquires from a macro level into the microcosm of human physiology and the mutual relationships between our body's internal workings and the external environment. Its highest goal is to master the fundamental principles that govern the human body in order to maintain health, and prevent and treat diseases. Under this view, TCM, as an integral part of Chinese culture, has been warmly welcomed and plays a critical role in Hong Kong's healthcare system.

Background of Hong Kong

As a Special Administrative Region, Hong Kong is a dynamic metropolis located at the southeastern tip ofthe People's Republic of China (PRC). With a population 7.31 million people, Hong Kong comprises 1105.7 squares kilometers and is composed of 462 islands with 4 main parts: Hong Kong Island, the Kowloon Peninsula, the New Territories, and Lantau Island. As the world's 9th largest trading economy, the city is often characterized with having skyscrapers and a high population density. In fact, it may be surprising that developed land in Hong Kong only accounts for 25%, while country parks and nature reserves take up nearly 40% (HKSAR, 2016) [1]. Therefore, a wide variety of local raw herbs can be readily found in the region, providing the essential element for a unique stream of TCM known as 'Lingnan Chinese Medicine Culture'.

Following British rule from 1842 to 1997, China assumed her sovereignty under the 'one country, two systems' principle. With its remarkable and unique history of British colonization passing over Chinese immigration, it comes as no surprise that Hong Kong developed into a melting pot of Eastern and Western characteristics. Hence, this cradle of well blended integrative culture and knowledge nurtures the integrative practice between TCM and western medicine.

History of TCM in Hong Kong

Development of TCM

As 91% of the population of Hong Kong is of Chinese decent (HKSAR, 2016), TCM is extensively accepted as one of the main remedies against illness. When Hong Kong opened its port to foreigners as a British colony, the public medical service was mainly provided by TCM practitioners instead of western medical doctors. Tung Wah Hospital, established in 1872, was the first public hospital in colonial Hong Kong. It is usually cited as a typical example of the major contribution of TCM to the general welfare of the city in the early days. Being the first hospital offering TCM treatment, Tung Wah helped about 45% of the population annually. In contrast, the Government Civic Hospital, primarily offering western medical services, barely assisted 1% of the total patients as Tung Wah in 1895 (Tse, 1998). As time elapsed and with the storm of cultural influences in China such as the “Self-Strengthening” movement (18611895), western medicine prevailed and took over the major role in health care. Over 100 years, TCM had been merely recognized as a traditional cultural convention (HKSAR, 2007) [2]. With the political adoption of non-intervention towards TCM's development, Chinese Medicine did not gain its statutory footing and subsequently waned in popular usage.

Despite the mainstream of the public healthcare system being provided by western medicine, TCM has historically played a key role in the safeguard of public health. According to a 1989 governmental study conducted by the Working Party on Chinese Medicine, 76% of the interviewees had visited a western medicine doctor during the 9 previous months while only 9% had sought treatment from TCM practitioners. Nevertheless, 42% of interviewees who were willing to seek further treatment stated that Chinese Medicine would be their choice as a second step care initiative. When local citizens were asked about the popularity of using TCM products, 66% respondents reported frequent intake of herbal soup as their means of healthcare, while 58% revealed drinking herbal tea (HKSAR, 2007). Conducted in 2000, the Thematic Household Survey Report No.3 [3] concluded that 15.5% of the population had consumed TCM products or food during the month before the enumeration. Among them, 63.3% reported that they consumed the products for regulating functional state of the body, followed by 30.0% for curing diseases and 10.6% for to unification. This information reveals that TCM is generally recognized as a secondary line of defense against illness.

In 1997, [4] Chinese medicine was first granted its official status by the Basic Law. According to Article 138 of the Basic Law, it states that “the Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region shall, on its own, formulate policies to develop western and traditional Chinese medicine and to improve medical and health services. Community organizations and individuals may provide various medical and health services in accordance with law” (HKSAR, 2016) [5]. Following the implementation of Basic Law, the Chinese Medicine Ordinance and Chinese Medicine Council were organized to regulate the development and practice of Chinese medicine practitioners (CMPs). In the years following the establishment of official regulations, much discussion ensued on developing Hong Kong into a “Chinese Medicine port”, similar to the Cyberport project in Pokfulam. Sadly, the proposal has never gotten off the ground. However, the Government has still made considerable investment in regulating and educating CMPs and has established 18 Chinese Medicine Centers for Training and Research (CMCTRs) with one in each district since 2003, in addition to regulating and promoting proprietary Chinese medicine (pCm) products.

In order to further develop the practice of TCM and facilitate the employment of CMPs, the Government acknowledged the need to develop an inpatient Chinese Medicine hospital as a platform for professional training. As the Chief Executive articulated in his policy address in 2014 (HKSAR, 2014) [6] and 2016 (HKSAR, 2016) [7], a site at Tseung Kwan O, has been reserved for construction with the aim of providing 400 inpatient beds (HKSAR, 2014) [8]. The aim of this site is to explore integrative medicine in a large hospital setting and create more training and employment opportunities in the field of TCM, especially for junior CMPs.

In addition to the hospital, the Government launched the "Integrated Chinese-Western Medicine (ICWM) Pilot Program” in 2014. To explore the feasibility and gain more first-hand experience for the investigation of an ICWM model, Phase One of the Program started with Tung Wah Hospital, Tuen Mun Hospital and Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital, based on stroke rehabilitation, palliative care for cancer patients, and acute low back pain rehabilitation respectively. In the program, patients enroll voluntarily and receive both consultations from the CMPs working in CMCTRs and WMPs from the corresponding hospital without any interference with the current Western Medicine treatment and the discharge plan of the enrolled patient. Phase Two has started and is currently covering 7 hospitals (HKSAR, 2014) [9]. Therefore, it is believed that the industry may turn the page after the disappointing proposal about the "Chinese Medicine Port”.

Education of TCM in Hong Kong

Before 1997

Before the handover to China, Hong Kong did not have any government funded tertiary education specialized in TCM. In 1917, Qingbao Chinese Medicine Evening School was established by Chen Qing Bao, a renowned CMP from Guangdong. Established as the first amateur TCM school, it came into being a year before Shanghai TCM Specialized Training College, the first TCM school in Mainland China. After the Second Sino-Japanese War, a significant number of TCM masters had immigrated to Hong Kong in order to escape from the unsteady political environment in Mainland China. With the massive reputation, the study of TCM blossomed and the number of private educational institutions specializing in TCM rocketed to more than 15 schools during the 1950's.

Being outside of the public healthcare education system, TCM education had been supported privately by TCM advocates and philanthropists. The course of study at the Chinese Medicine Institute (CMI), which was established in 1947, was a prime example of a comprehensive TCM education. As the first school to provide a systematical TCM education, this pioneer program created a blueprint for TCM education in future. It offered a 3-year undergraduate and a 4-year master's course of study with the content composed of both western and traditional Chinese medical knowledge such as physiology, pathology, acupuncture and internal medicine. In 1998, the same year as the establishment of the School of Chinese Medicine in Hong Kong Baptist University (HKBU) [10], CMI decided to close its doors. CMl's well respected program, which had attracted students from Asia to America, embraced its 50th anniversary and ended its mission due to the repetitive ambition in TCM education as HKBU (Chan, 2015) [11].

After 1997

Acknowledging TCM as a vitally important sector of healthcare system, the Government started to further modify and regulate the development of TCM in Hong Kong. As a result of the passing of Article 138 of the Basic Law, Chee-hwa Tung, the first Chief Executive, stated that “For the protection of public health, we aim to introduce a bill in the next legislative session to establish a statutory framework to recognize the professional status of traditional Chinese medicine practitioners; to assess their professional qualifications; to monitor their standards of practice; and, to regulate the use, manufacture and sale of Chinese medicine” (HKSAR, 1997).

Following the policy address in 1997, HKBU became the first institution funded by the University Grants Committee (UGC) to offer higher education in TCM in Hong Kong. It launched the first Bachelor of Chinese Medicine and Bachelor of Science (Hons) in Biomedical Science program in 1998, and then established the School of Chinese Medicine (SCM) in 1999. Taking a step further, HKBU also launched a Bachelor of Pharmacy (Hons) in Chinese Medicine program, the only one of its kind in Hong Kong. Together with the launch of bachelor programs in Chinese Medicine by the Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK) in 1999 (Derek G & Robin G [12] and the University of Hong Kong (HKU) in 2002 (HKU, 2010) [13], there are only three officially recognized local universities offering Bachelor's degree or above programs on TCM in Hong Kong.

Unlike China and Japan, western medical practitioners (WMPs) in Hong Kong do not have the legal authority to prescribe CM herbs. Similarly, CMPs are also not permitted to prescribe any western medications and use western medical diagnostic equipment, which is different from the situation in Mainland China. Notwithstanding the difference in scopes of practice, CMPs have been responsible for mastering fundamental western medical knowledge for the sake of better communication and collaboration between WMPs and CMPs. Since the official establishment of Bachelor degree in Chinese Medicine in universities, and with the growing demand for integrative medical practices in the areas such as cancer care, pain syndromes, psychiatric disorder, chronic diseases and geriatrics, CM education in Hong Kong meets the development of integrative medicine and has thus sharpened the competitive edges of CMPs in Hong Kong.

According to the latest report from the Government, the number ofnew students in the 6-year bachelor's program averages steadily around 90 each year. The comprehensive program covers Chinese Medicine practice and herbal medications, as well as basic knowledge of Western Medicine. Arranged by the universities under the collaboration with 18 CMCTRs, which are operated on a tripartite collaboration model involving the Hospital Authority, non-governmental organizations and local universities, and Chinese Medicine hospitals like Guangzhou Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine in the Mainland, clinical internship placements for students are completely guaranteed. Additionally, fresh graduates from local full-time TCM bachelor programs can also decide to apply to work in the CMCTRs as junior Chinese medicine practitioners in the first year, and as Chinese medicine practitioner trainees in the second and third years. Since January of 2014, the CMCTRs have employed a total of 224 graduates (HKSAR, 2014) [14]. With these numbers as evidence, it can be confidently stated that CMCTR system is ripe for success in the contribution of TCM education, and thus its sustainable development.

Human Resources of TCM in Hong Kong

Before 1997

Regarding the practice of TCM practitioners, the Institute of Chinese Medicine (ICM) in CUHK conducted a survey to review the practice before 1989. Three categories of practices were summarized in the study, namely TCM practitioners, acupuncturists and Chinese chiropractors. Despite the differentiation of TCM practices into 3 groups, it pointed out that a majority of the CMPs would blend them all in daily practice in a bid to provide an individual treatment for the patients. Besides some working for the non-profit organizations, a convincing majority of the CMPs were self-employed or hired by TCM herbal retailers in a small and unpleasant shop (HKSAR, 2007) [15]. It was concluded that the development of TCM had been constricted by the lack of government involved clinics.

After 1997

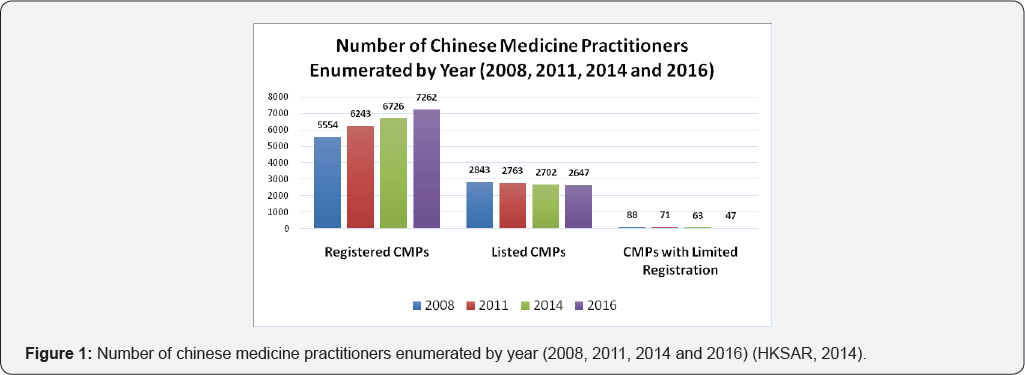

Fostered by the implementation of the Chinese Medicine Ordinance after 1999 (HKSAR, 2007), TCM became ground in its statutory footing and embraced its blooming. With the support of a series of CM development policies, the CM clinics were modernized by computerized CM information systems to manage pharmacy, consultation records and administration. According to 2017 data from the Department of Health, the total number of Chinese Medicine practitioners reached 9, 956 people, which composed of 7262 registered practitioners, 47 practitioners with limited registration and 2647 listed practitioners, while the number of western medical doctors was reported as 14,013. With a population of 7.37 million people, the ratio of TCM practitioners to people would be 1:744, with the ratio of western doctors as 1:526 (HKSAR, 2017). In spite of the tremendous gap between two ratios, the proportion of citizens choosing Chinese medicine is far lower than those preferring western medical initiatives. Amongst those who received outpatient services in 2005, 80.23% consulted WM doctors, 3.17% visited TCM practitioners only, while 16.60% used both Chung CH, Lau CH, et al [16]. With the assumption that barely 20% of citizens tend to visit TCM practitioners, the ratio skyrockets from 1:744 to 1:149. Due to governmental overestimation of the necessity of the number of CMPs, Hong Kong is facing the oversupply of CMPs in recent years.

Additionally, the "Scheme for Admission of Hong Kong Students to Mainland Higher Education Institutions” has escalated number of fresh graduates coming from the universities in the Mainland since 2012. For example, Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine (GZUCM), one of the 4 earliest tertiary educational organizations specializing in TCM in China, recruited 152 Hong Kong students via the scheme in 2015 (HKSAR, 2015) [17], which is more than the annual sum of fresh graduates from 3 local universities. With 30 Mainland universities like GZUCM offering the recognized full-time bachelor programs in TCM, more and more HK students cross the border and study TCM because of their lower admission requirements. It is inconceivable how intense the competition of TCM practitioners would become if the situation continues.

Concerning the regulation of the number of TCM practitioners, Chinese Medicine Practitioners Licensing Examination is the second point of modulation after the intake number of full-time bachelor's undergraduates. According to the official figures, the passing percentage is 44.9% in 2014 (Chinese Medicine Council of Hong Kong, 2014) and 42.9% in 2015 (CMCHK, 2015) [17], which is equivalent to more than 200 new CMPs entering the industry each year. While an immense gap between the demand in Chinese Medicine and Western Medicine presents in the above data, the number of annual newcomers for CMPs reaches nearly the half of that for western doctors (HKSAR, 2013) [18] (Figure 1-5) (Table 1).

In the aspect of the characteristics of active CMPs, the government statistics revealed that the sex ratio (males per 100 females) of the active practitioners enumerated decreased from 264 in 2008 to 196 in 2014, indicating the trend of increase in female CMPs. For the sector of work, the largest proportion has been in the private sector, which employed more than 85% of the registered CMPs and 95% of the listed CMPs, from 2008 to 2014, followed by the Hospital Authority (HA) (4.7%), the subvented sector (4.6%) and the Government and academic sectors (2.6%) (HKSAR, 2014).With the high demand for CMPs in the public sector, it is a disappointing fact that most practitioners stay in the private sector. Having this vast imbalance, the public sector has to encounter a discouraging shortage of talents. The same survey also revealed that the median age of the active registered CMPs enumerated was 60.0 years for those working in the private sector while the ones for the HA, the subvented sector and the Government and academic sectors are 30.0 years, 33.0 years and 37.0 years respectively (HKSAR, 2014). With the figures above, it is a plain fact that most CMPs working in non-private sectors substantially belong to the young generation. With the favor from the policy that CMCTRs are required to employ at least 12 junior CM practitioners or trainees (HKSAR, 2014), it is deduced that the CMCTRs has made magnificent contribution to the employment of the graduates in TCM from universities. With the hope of the establishment of CM hospital and the ICWM pilot program, it is believed that the demand for TCM practitioners and the allurement for junior CMPs staying in non-private sectors can be furthered stimulated in the future.

Current System in Hong Kong

Categories of TCM practitioners

Under the Chinese Medicine Ordinance (CMO) (Cap. 549 of the Laws of Hong Kong passed on 14 July 1999), the Chinese Medicine Council was set up simultaneously for the sake of the regulation for CM as stipulated in the CMO. After the handover in 1997, three types of CMPs in Hong Kong are admitted to practice Chinese Medicine under the regulation of law. Among all three categories, registered Chinese medicine

Following the registered CMPs, listed Chinese Medicine practitioners ranked second at 37.6%, with the Chinese Medicine practitioners with limited registration at a mere0.78% (HKSAR, 2016) [19].

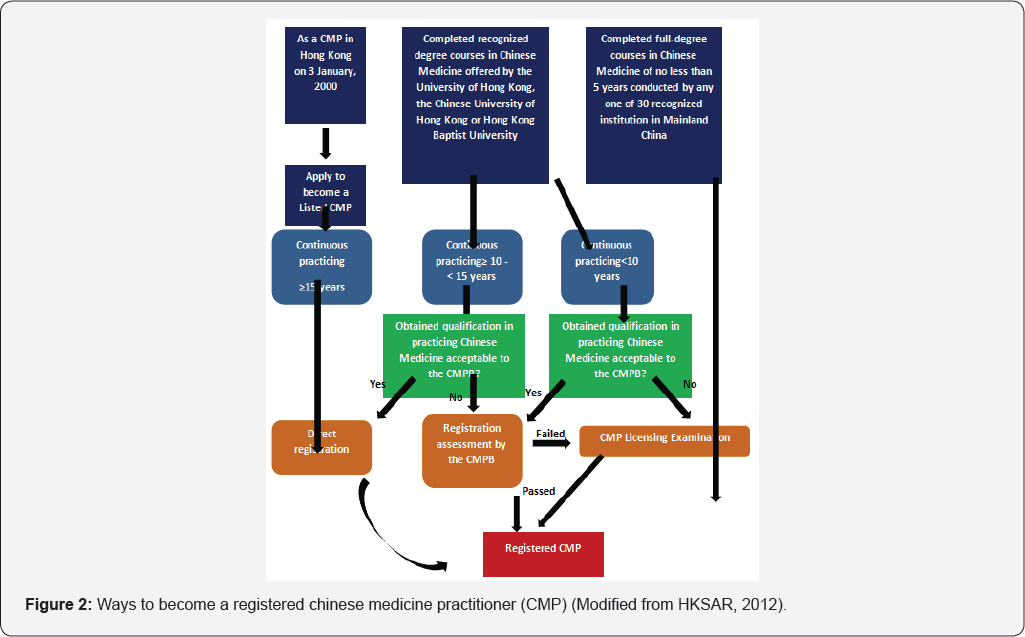

Since TCM has been prevalent in Hong Kong for more than 100 years, a significant number of CMPs had practiced before the establishment of the statutory regulatory system for CMPs. To set up a transitional arrangement, these practitioners, practicing long before January 2000, are allowed to continue their practice as listed CMPs in the interim. Based on their practicing experience and academic qualifications, these listed CMPs were allowed to apply for the registration without taking any examination or assessment if they continuously practice for not less than 15 years, or for not less than 10 years with recognized academic qualifications. For those with at least 10 years of continuous practicing experience but without recognized academic qualifications, or with less than 10 years of continuous practicing experience but with recognized academic qualifications, they could obtain the registration by passing a one-off "Registration Assessment”. Nonetheless, the Licensing Examination for registered CMPs is compulsory if they fail the Assessment (HKSAR, 2006) [20]. To this day, the end date of the transitional period has not been disclosed. With the termination of application for the listed CMPs in 30th December, 2000, it is expected that the listed CMPs may eventually be replaced by registered CMPs in future.

With regard to the CMPs with limited registration, this category is reserved for non-Hong Kong registered CMPs who perform clinical teaching or research in CM for a specified educational or scientific research institution. Not only do they have to renew the registration annually by the institution, but they are also limited to perform the specified clinical teaching or research in the specified institutions, and are not allowed to practice privately in Hong Kong (CMCHK).

During the period of transitional arrangements, both listed CMPs and CMPs with limited registration are permitted to practice legally in Hong Kong like registered CMPs. However, the listed and registered CMPs differ from their legal rights in various aspects. According to the CMO, only registered CMPs are allowed to prescribe Schedule 1 (potent or toxic) Chinese herbal medicines of the CMO.

In addition to the authority of the prescription, registered CMPs and listed CMPs differ in the titles and certificates shown in the working places. Prior to a shift in December of 2006, CMPs were not given legal recognition to issue sick leave certificates. This hindered CM services to be regarded as one of the officially recognized means for curing diseases. After the amending of the Employment Ordinance, only sick leave certificates issued by registered CMPs and CMPs with limited registration became recognized. It is believed that the above measures will encourage the registration of CMPs, especially to listed CMPs.

Health insurance

Unlike Japan, Hong Kong does not have any national health insurance scheme at the moment. Under the 'one country, two systems' principle, Hong Kong did not follow the establishment of government health insurance system in China. Currently, health insurance is offered by the private sector. Traditionally, most private insurance plans did not cover CM treatment and most CMPs did not purchase any professional liability insurance. With official recognition of sick leave certificates issued by registered CMPs and CMPs with limited registration in 2006, a majority of insurance plans and medical benefits began to include CM services, usually with a limit on the number of annual visits. CMPs also began to purchase liability insurance to obviate the full cost of defending against a negligence claim made by a client, and damages resulting from a civil lawsuit.

According to the Thematic Household Survey conducted by Census and Statistics Department in 2014, 48.7% of interviewees were entitled to medical benefits provided by employers or companies, or covered by medical insurance purchased by individuals. Among these interviewees, 19.6% of them cited coverage for Chinese Medicine services, followed by consultation with Western medicine practitioners (WMPs) (64.5%), with 90.3% citing coverage for hospitalization, the most commonly covered service. Focusing on persons covered by medical insurance purchased individually, the survey indicated that the great majority (98.5%) had the coverage of hospitalization, followed by consultation with WMPs (12.9%) and that with CMPs (5.9%).Looking at the number of doctor visits made 30 days before the enumeration from both practitioners of Chinese and Western medicine, the report analyzed that only 26.7% of such consultations were fully or partly covered by medical insurance or subsidized by employers (HKSAR, 2014). Taking the points above into consideration, it is believed that a significant proportion of population is still beyond the protection from healthcare insurance.

To investigate the reasons behind, the survey provided a possible explanation pointing to the net consultation fee of the doctor visits. After deducting the amount reimbursed by employers or insurance companies and the amount paid by Elderly Health Voucher, and excluding consultations with unknown consultation fees, the median net consultation fee per consultation made with a private medical practitioner, no matter a western or Chinese one, was HK$220, equal to ¥3263.2 (1 HKD = 14.82877 JPY) (HKSAR, 2014). Referring to the Hong Kong Annual Digest of Statistics 2016 Edition [21] conducted by Census and Statistic Department, the median monthly employment earnings of employed persons enumerated in 2015 is HK$14,500, equivalent to ¥215112.53 (1 HKD = 14.82877 JPY). From the figures collected above, it can be seen the consultation fee as an affordable expenditure, which occupies barely 1.5% of the total monthly income. With all of the support initiatives from public hospitals and institutions, many may still think that the purchase of health insurance for anything outside of hospitalization is not a necessity.

Nevertheless, with the ageing population, it is an incontrovertible and disheartening fact that the public expenditure in healthcare sector would rise dramatically, leading to a financial burden in future. Hong Kong, running a dual-track healthcare system by which the public and private healthcare sectors complement each other, is being confronted by the escalating medical costs and public expectation of healthcare services. With substantially increasing expenditures on medical and healthcare services by over 60% over the past seven years (HKSAR, 2015) [22], the Government launched a public consultation on healthcare reform to probe into the long-term sustainable development of the system. Notwithstanding the support for the reform, the public has expressed reservations about mandatory financing insurance. As a result, the Health Protection Scheme (HPS) proposal, a voluntary, governmentregulated private health insurance scheme, was consulted in 2010 (HKSAR, 2015) and the scheme, named as 'Voluntary Health Insurance Scheme' (VHIS), was set to implement in phases from 2017 (Ko W. M., 2016) [23]. With the implementation of VHIS, it is hoped that the balance between public and private healthcare systems can be refined, stimulating a better use of private healthcare services, including by which the majority of Chinese Medicine practitioners are providing, as an alternative to public services.

Law restriction of TCM

As mentioned in Section 4.1, the practice of CMPs and the use, trading and manufacture of Chinese medicines are regulated by the Chinese Medicine Council of Hong Kong (CMC) under the Chinese Medicine Ordinance (CMO). According to the CMO, Chinese herbal medicine is defined as herbal substances specified in Schedule 1 and Schedule 2 of the Ordinance. While Schedule 1 includes 31 types of potent or toxic Chinese herbal medicines, such as unprocessed Radix Aconiti, Cinnabaris, Radix Sophorae Tonkinensis, Schedule 2 contains 574 types of commonly used Chinese herbal medicines, such as Medulla Junci, Radix Codonopsis, Concha Haliotidis. For Schedule 1 herbs, it is not permitted to sell by retail or wholesale, or dispense to others, or possess for the purpose of wholesale, except in accordance with a prescription given by a registered CMP, or with a retailer license or a wholesaler license in respect of such Chinese herbal medicine (HKSAR, 2016).

Schedule 1 is edited based on the pragmatic situation in Hong Kong and the potent or toxic Chinese herb medicines regulated in China. Being relatively potent or toxic, these 31 medicines are regulated by strict rules and stored by special methods. For Schedule 2, in addition to the currency of Chinese herb medicines in the local market, CMC referenced 'Pharmacopoeia of the People's Republic of China' and the "Chinese Materia Medica”, (written by Xu Guojun, etc.) to populate the list, with the exclusion of herbs which can be used in other aspects or as ordinary food ingredients (HKSAR, 2007). With the regulation on these Chinese herb medicines commonly involved in the prescription of CMPs, the safety and appropriateness of purchase, retail and utility can be guaranteed.

Aside from Schedule 1 and Schedule 2, the establishment of Hong Kong Chinese Materia Medica Standards (HKCMMS) contributes a lot to the safe use and the quality of Chinese herbal medicine. To foster standards for ordinarily used Chinese medicine in phases, HKCMMS was first launched in 2002. With the publication of the 'Hong Kong Chinese Materia Medica Standards (HKCMMS) Volume 8' in March 2017, the standards for a total of 275 CMM have been established. The quality of individual Chinese herbal medicines, the raw material for proprietary Chinese medicines (pCm), has an immense and direct impact on pCm products. lt is vitally important for the Government to safeguard the quality of pCm and set up a corner stone for further research on Chinese medicines and products.

During the development of HKCMMS, adequate representative samples authenticated by experts were obtained from Mainland and Hong Kong with the aid from the State Food and Drug Administration (SFDA). Deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) fingerprint technology (HKSAR, 2015) [24] and high-performance liquid chromatographic fingerprinting are the examples of methods for authentication of Chinese medicines, in addition to the conventional means like thin-layer chromatography. The limits of heavy metals, pesticide residues, mycotoxins (aflatoxins) for each Chinese medicine and the determination of its foreign matter, ash, water content, extractives and assay limits are regulated (HKSAR, 2005) [2 5]. Conducted by research teams composed of six local universities, namely the Chinese University of Hong Kong, City University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong Baptist University, Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong University of Science and Technology and the University of Hong Kong, and the National Institutes for Food and Drug Control (NlFDC) of the People's Republic of China and Taiwan's China Medical University, the research work is greatly recognized by the industry.

lnitiated and supported by the Panel on Promoting Testing and Certification Services in Chinese Medicine Trade under the Hong Kong Council for Testing and Certification, the Hong Kong Certification Scheme for CMM was launched in 2014 by the Productivity Council to further solidify the status of herbal medicine testing center in Hong Kong. The Certification Scheme is a voluntary program which certifies herbal medicine suppliers who offer products in compliance with the standard requirement set in HKCMMS. By promoting quality assurance through high standards, the Scheme helps traders and suppliers draw the attention of consumers. Additionally, a Chinese medicine testing center will be set up in future, as promised by the Chief Executive of HKSAR in his 2015 Policy Address (HKSAR, 2015). lt is believed that the launch of such policies may expedite the internationalization of Chinese medicine industry in Hong Kong.

ln order to offer additional guidance to pCm product manufacturers on top of the regulation of pCm products by the CMO, the Chinese Medicines Board under CMCHK issued the 'Hong Kong Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) Guidelines for Proprietary Chinese Medicines' in 2003. GMP guidelines, as a quality assurance system widely adopted by the drug manufacturing industry worldwide, guarantees the manufacture of safe and consistent quality goods via establishing standards for drug production hardware and software, from quality control, personnel, equipment to laboratory experiments. Through the diminishment of risks inherent in manufacturing processes, such as cross-contamination of ingredients, the public health of herbal medicine consumers can be safeguarded. Issuing GMP certificates, the Government can facilitate the standardization, modernization and internationalization of the pCm manufacturing industry. By labeling the products with 'GMP', the companies can boost their public confidence and open up their global market (HKSAR, 2014). lt is intended that the initiatives will help the industry further develop and expedite the exploration of the international market.

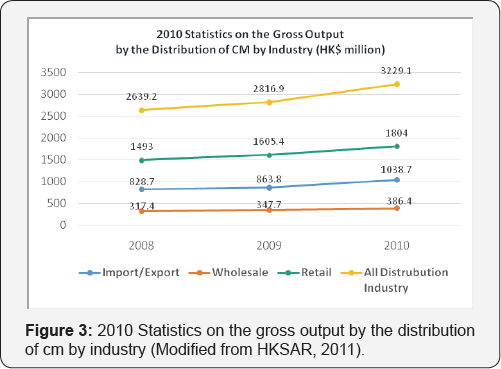

Market Size in Hong Kong

Since the official supportive initiatives were launched in 1997, Chinese medicine industry has grown into one of the main industries in the healthcare sector. According to the list on the website of Chinese Medicine Council of Hong Kong, as of December 2016 [26], retailers and wholesalers of CM herbs number 4654 and 933, while manufacturers and wholesalers of pCm are 275 and 25. According to the latest Hong Kong Monthly Digest of Statistics featuring Chinese Medicine in 2011, the number of persons engaged in the industry of import or export, wholesale and retail of Chines Medicine are 1806, 1395 and 4824 respectively. In 2010, the report stated that the total gross output of the distribution of CM industry reached HK$3.2291 billion, increasing substantially from $2.6392 billion in 2008. It is foreseeable that its gross output is in an upward trend and will continue growing. From the statistics, the highest gross operating surplus belonged to the retail with HK$506.2 million, followed by the import/export sector with HK$408.8 million, and HK$126.6 million by the wholesale sector. From the point of view for analyzing value added as a percentage of gross output, the industry of wholesale of CM was the highest among all three categories at 67.9% in 2010. Since the launch of the Individual Visit Scheme to Hong Kong in 2003, and because of the superb reputation of the safety and quality of Hong Kong products, it is believed that the retail and wholesale industry of CM is significantly supported by consumers from mainland China, which can only add to the positive growth numbers.

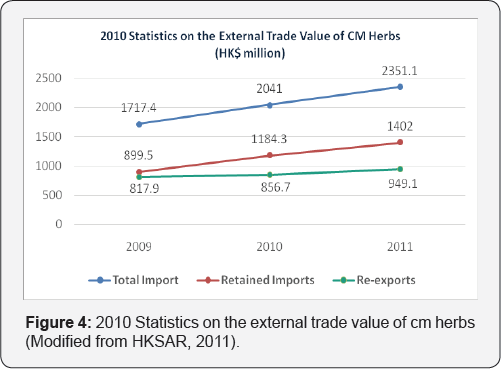

As a critical, international trading center, Hong Kong also plays an essential role in the trading of Chinese medicinal herbs. Historically, Hong Kong has been serving as a port linking China with other corners around the world. Undoubtedly, CM herbs grown and harvested in China are mostly exported to the world via Hong Kong. In 2011, the value of imports of CM herbs amounted to HK$2.35 billion, escalated by 15.2% from 2010. Of these imported herbs, a representative portion of them was consumed locally with HK$1.40 billion. This reflects the considerable local demand for CM herbs in Hong Kong for medical use or manufacture. With regard to re-exports of CM herbs in 2011, the value climbed up to HK$0.95 billion, climbed by 10.8% in 2010. Taking a whole view of the picture, it is indisputable that the CM industry in Hong Kong is climbing in trend throughout recent years. In the analysis of the statistics, Mainland China was still the top supplier of Hong Kong's imports of CM herbs with the sharing as 26.0%, followed by Canada (21.1%), Japan (13.7%), Korea (12.9%) and the United States of America (9.8%). However, Japan ranked first with 23.7% when it comes to the value of Hong Kong's re-exports of CM herbs, followed by Taiwan (14.5%), Korea (12.6%), the US (10.3%) and Canada (10.2%). It is believed that the reason behind relates to the soaring popularity of using CM herbs among the top three places of the re-exports value via the practices of TCM in Taiwan, Kampo in Japan and traditional Korean medicine in Korea.

Harvest Place of Raw Herbs

From the same statistics in 2011 mentioned in section 5, the re-export of CM herbs counted for more than 99%, if not all, of the total exports. It reflects the lack of the export of local CM herbs and the significant reliance on the supply from China, echoed with the description in the publication, A New Era of Chinese Medicine in Hong Kong, by Chinese Medicine Division of Department of Health in 2007. This book states that there are over 900 species of CM herbs in the market at the moment but over 90% of them are imported from all over the world (Zhao ZZ & Jiang ZH) [27]. Notwithstanding that most (40%) Ginseng imported comes from the US, 80% of other CM herbs are primarily imported from Mainland China (HKSAR, 2007). Similar to the situation in Hong Kong, 81.8% of raw herbs in Japan are imported from China (Japan Kampo Medicines Manufacturers Association, 2013) [28]. Hence, the harvest and price of raw herbs in China make immense impact to the price of herb-related products and services. With the points mentioned above in mind, it is reasoned that the development of CM industry in Hong Kong is intimately related to the one in China.

Cost of Concentrated Chinese Medicine Granules

In the past decade, apart from the utilization of raw herbs or prepared drug in pieces, the market share of concentrated Chinese medicine granules (CCMG) has kept a steep pace. The traditional dispensation, preparation, and boiling of CM herbs into a consumable decoction is time-consuming and inconvenient. Additionally, raw herbs require specific storage conditions and a considerable amount of storage space. These two issues of the time and space requirements provesto be a challenge for providers of Chinese medicine to popularize its use in the modern age. By the invention of CCMG, modernized extraction and concentration technologies have been developed to replicate the traditional method of preparing medicinal decoction from raw CM herbs. It is believed that this concentrated granule is the solution that CM product manufacturers and providers are looking for.

When it comes to CCMG in Hong Kong, Nong's® is often cited as a typical example. According to Euro monitor report, in terms of prescription revenue in 2014 (PuraPharm, 2015) [29], Nong's is the largest supplier of CCMG in Hong Kong, taking up 70% of the market share. Leading the CCMG market, Nong's has been supplying CCMG to the majority of hospitals and clinics in Hong Kong, along with all 18 CMCTRs. Presently, there are no official reports by the Government about the investigation of the market share between raw herbs and CCMG. If we take a look at the industry development in China, a similar trend may be deduced via the figures. According to the same report, the market share of CCMG products in the PRC traditional Chinese herbal medicine market increased from 3.4% in 2010 to 4.0% in 2014. It is believed that the share would continue growing due to the convenience and time efficiency of CCMG products, and the broader coverage of state medical insurance reimbursement policy. During the same period from 2010 to 2014, the retail sales value of the PRC CCMG product market rose at a compound annual growth rate of 40.7%, meeting RMB 7,829.2 million, approximately¥132 billion (1 CNY = 16.8888 JPY), in 2014.

From the data above, it can be deduced that the demand of CCMG products and its market share will escalate similarly in Hong Kong under a resembling practice and culture. Since the majority of the raw herbs are sourced from Mainland China, the price of CCMG products relates closely to the price of raw herbs. Therefore, the manufacturers in Hong Kong, like Nong's, have set up their factories in China and made agreement with the local herb farms, sometimes even set up self-owned planting farms in order to guarantee the stability of the price and supply of raw herbs.

From the order form of Nong's CCMG products renewed in February 2016, the list price of a bottle of Kakkonto CCMG product (prescription drug), as a common example, is at HK$328 (¥4,863.8, 1 HKD = 14.82877 JPY) for 200g while the wholesale price is HK$164 (¥2,431.9, 1 HKD = 14.82877 JPY). Since the suggested dosage is 5g/b.i.d., the daily list price of two dosages would be ¥243.19 and the daily wholesale price would be ¥121.60. Compared with the Nong's product, the Kakkonto product (prescription drug) by Tsumura & Co. is ¥8.70 for 1g, making ¥65 daily for 7.5g.

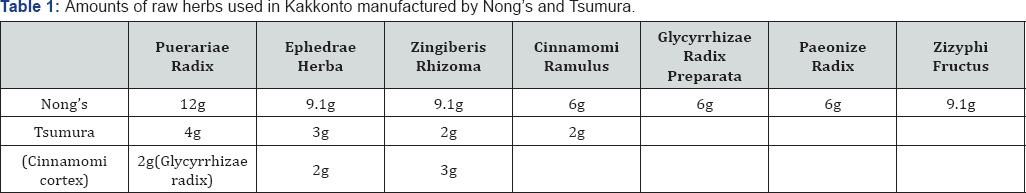

Apart from the higher price for daily dosage, the CCMG product in Hong Kong has a higher concentration for the extracts from raw herbs. For the Kakkonto CCMG products of Nong's, the daily dosage of Puerariae radix (Kakkon), Ephedrae herba (Mao), Zingiberis rhizoma (Shouga), Cinnamomi ramulus (Keishi), Glycyrrhizae radix preparata (Shakanzo), Paeonize radix (Shakuyaku) and Zizyphi fructus (Taiso) is equivalent to 12.0g, 9.1g, 9.1g, 6.0g, 6.0g, 6.0g and 9.1g respectively. However, in the view of the product by Tsumura & Co., the daily dosage of the above raw herbs equals to 4g, 3g, 2g, 2g, 2g, 2g and 3g correspondingly, of which Cinnamomi cortex (Keihi) and Glycyrrhizae radix (Kanzo) are used to replace Keishi and Shakanzo respectively (Japan Kampo Medicines Manufacturers Association, 2007). From the figures above, it may be a surprising fact that the dosage in Kampo is merely one third of that in TCM. The noticeable difference between two products in Hong Kong and Japan reflected the different prescription practice and theories between TCM and Kampo.

Conclusion

Passing through a long history and a series oftransformations, traditional Chinese medicine has been playing a vital role to safeguard the healthcare of the people of Hong Kong. Eventually gaining its statutory footing, CMPs are now regulated by the Government and through the Chinese Medicine Ordinance, and are nurtured by comprehensive and systematic educational curriculum. With CM herbs and pCms being guaranteed by GMP and the Hong Kong Chinese Materia Medica Standards, private insurance plans and the establishment of CMCTRs support CM services are involving into the public healthcare sector. Like the situation in Japan, the CM industry in Hong Kong relies on China in various aspects, from the purchase of pCm products to the supply of CM raw herbs. With growing demand for CM services and products from locals and Chinese visitors, in addition to the widespread utilization of CCMG, it is foreseeable that the market share of CM will continue to grow. With the renowned reputation for quality control of products and sophisticated education system for CMPs and Kampo practitioners, it is anticipated that the collaboration and academic exchange between Japan and Hong Kong may become more frequent and firm in the future.

References

- (2016) Census and Statistics Department, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Government. Hong Kong Annual Digest of Statistics Edition.

- (2007) Chinese Medicine Division, Department of Health, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Government. A new era of chinese medicine in hong kong.

- (2000) Census and Statistics Department, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Government. Thematic Household Survey Report No. 3.

- (1997) Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Government. Hong Kong Policy Address 1997.

- (2016) Chinese Medicine Division, Department of Health, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Government. Development of Chinese Medicine in Hong Kong.

- (2014) Chinese Medicine Division, Department of Health, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Government. Pamphlet on Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) for Proprietary Chinese Medicines.

- (2016) Department of Health, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Government. Health Facts of Hong Kong.

- (2014) Chinese Medicine Council of Hong Kong. Newsletter of the Chinese Medicine Practitioners Board, 38.

- (2014) Department of Health, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Government. 2014 Health manpower survey - summary of the characteristics of chinese medicine practitioners enumerated.

- School of Chinese Medicine, Hong Kong Baptist University. SCM Booklet.

- Chan, WK (2015) Synopsis on the education and inheritance status of chinese medicine in hong kong before 1997. Hong Kong Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine 10 (4): 1-2.

- Derek G, Robin G (2002) Traditional Chinese Medicine, The Hong Kong Health Sector: Development and Change: 84-93. Hong Kong: Chinese University Press, Hong Kong.

- (2010) School of Chinese Medicine, the University of Hong Kong. Teaching.

- (2014) Food and Health Bureau, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Government. Voluntary Health Insurance Scheme - Executive Summary.

- (2007) Japan Kampo Medicines Manufacturers Association. 014 Kakkonto.

- Chung CH, Lau CH, Yeoh EK, Griffiths SM (2009) Age, chronic non- communicable disease and choice of traditional Chinese and western medicine outpatient services in a Chinese population.

- (2015) Chinese Medicine Council of Hong Kong. Newsletter of the Chinese Medicine Practitioners Board, 41.

- (2013) Food and Health Bureau, Hospital Authority, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Government. Legislative Council Panel on Health Services: Improvement of Doctors' Working Hours in Public Hospitals.

- (2016) Department of Health, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Government. Report on Strategic Review on Healthcare Manpower Planning and Professional Development.

- (2006) Health, Welfare and Food Bureau, Department of Health, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Government. Legislative Council Panel on Health Services: Registration of Chinese Medicine Practitioners.

- (2016) Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Government. Hong Kong - the Facts.

- (2015) Education Bureau, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Government. Handbook on the scheme for admission of hong kong students to mainland higher education institutions (2016/17).

- (2016) Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Government. The 2016 Policy Address: Innovate for the Economy, Improve Livelihood, Foster Harmony, Share Prosperity.

- (2015) Hong Kong Chinese Materia Medica Standards Office. Hong Kong Chinese Materia Medica Standards Volume 7.

- (2005) Hong Kong Chinese Materia Medica Standards Office. Hong Kong Chinese Materia Medica Standards Volume 1.

- Ko WM (2016) Press Release: [The Speech about Voluntary Health Insurance Scheme and Bazaars by the Secretary for Food and Health].

- Zhao ZZ, Jiang ZH (2004) Research and Practice of Chinese Medicine. 18 (6): 6-9.

- (2013) Japan Kampo Medicines Manufacturers Association 88.

- (2015) PuraPharm. EPURA-20150622-05.PDF.