Milestones on the Road Less Travelled: Teaching Complementary and Alternative Medicine in Medical Schools In the Age of Competency-Based Education

Michael Sanatani* and Jawaid Younus

Associate Professor of Oncology, Western University, Canada

Submission: May 10, 2017; Published: May 30, 2017

*Corresponding author: Michael Sanatani, Dipl.-Biochem., MD, FRCPC, Associate Professor of Oncology ,Schulich School of Medicine and Dentistry, Western University, 790 Commissioners Road East N6H 4L6, London, ON Canada, Tel: +1 519 685 8640; Fax: +1 519 685 8624; Email:

How to cite this article: Michael Sanatani, Jawaid Younus. Milestones on the Road Less Travelled: Teaching Complementary and Alternative Medicine in Medical Schools In the Age of Competency-Based Education. J Complement Med Alt Healthcare. 2017; 2(3): 555588. DOI: 10.19080/JCMAH.2017.02.555588

Abstract

Medical education is undergoing significant changes around the world. In order to remain relevant as a part of medical curricula, complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) content delivery methods and learning goals need to evolve as well. This represents an opportunity for CAM education and for medical schools to work together to enhance vital skills to be developed in graduating physicians.

Keywords: Competency-based education, Curriculum, Entrustable professional activities

Introduction

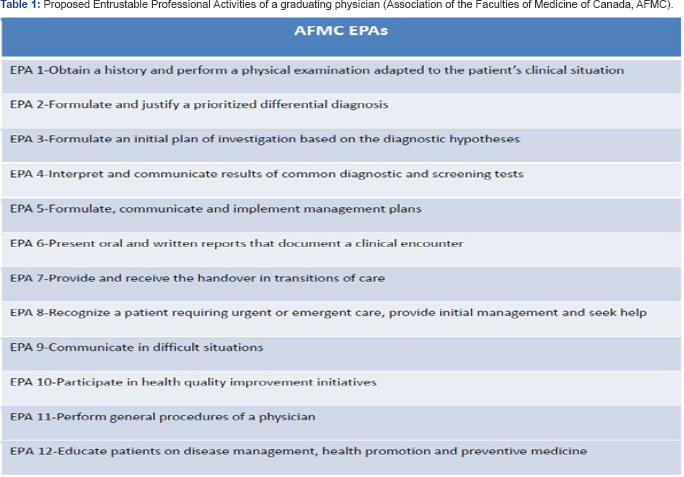

Medical education is a highly complicated enterprise. Not only is medicine, the subject matter, constantly in development, but societal attitudes towards health and illness are as well. In addition to knowledge, a medical trainee also has to acquire skills and attitudes [1] and overcome personal challenges there, while simultaneously deciding on a specialty best suited to their aptitudes and circumstances. Currently, in the attempt to improve the preparedness of the graduating physician for the tasks facing them in their career in all these dimensions, the focus in medical education is shifting from the provision of content to be learned, to observations of the outcomes of teaching in individual trainees. Outcomes-based education (OBE) or Competency-based Medical Education (CBME) are the buzzwords around the world in 2017 and likely for some time to come. Curricular committees in all continents are moving from course objectives to milestones in a trainee's educational trajectory, and from goals to entrustable professional activities (EPAs) which are to be observed. An example is given in table 1 [2].

This housecleaning is, overall, laudable. As educator and writer Marcel Prenskyrecommends in his pragmatic vision for curricular reform, "Don't teach useless information!” [3]. Many medical schools are reducing lecture time across many specialties in favour of small group learning and practical experience modules. However, there is of course the risk that new subject areas or those with a somewhat tenuous status may be threatened in this revision. Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) is just becoming established in conventional medical schools, mainly at the behest of interested students.

The need to incorporate familiarization with CAM in courses offered to the medical students has been expressed for at least 20 years by most of the education authorities and the government sector in several countries, including the United States, Korea, Canada, and the United Kingdom [4]. However, the uptake of such recommendations in the medical school curricula has been fairly slow. It is clear from various surveys and studies that majority of junior and senior medical students favor including basic knowledge about CAM in the medical curriculum, within the pre- clinical modules or clinical time [5,6]. The UK General Medical Council advocates that medical graduates should be aware of the range of CAM and the evidence behind it [7]. Several US and most Canadian medical schools have already incorporated some CAM knowledge in the medical curricula [8].

The challenge now to medical schools, and to the complementary medicine community, is to allow CAM teaching to stay relevant as a component of a competency-based curriculum. How can we move beyond a small amount of knowledge "about” complementary medicine, to a CAM-related skill that can be observed and even “entrusted” to a new graduate? Clearly, the answer cannot be skill incompetently performing complementary medicine; that would be appropriate for a complementary medicine school or training programme.

In a 2010 survey by Nicolao et al. [9] of Swiss physicians, CAM practitioners, and senior medical students, respondents were asked to rank what they felt were the most important goals of having CAM education in the curriculum. Although not classified as such in the study, response options included goals related to knowledge (“Provide knowledge about CAM drugs”, “Identify strengths and weaknesses of different CAM topics”, etc.), attitudes (“Promote collaboration with alternative health care clinicians”, etc.) and skills (“Enable the students to form their own opinion about CAM”, “Enhance patient-physician communication”, “Learn to talk to patients about CAM in a neutral way”). A highly ranked goal by all three groups of respondents was “Enable the students to form their own opinion about CAM” “Enhance patient-physician communication”, “Learn to talk to patients about CAM in a neutral way”). A highly ranked goal by all three groups of respondents was “Enable the students to form their own opinion about CAM”. Enhancing communication and learning to talk to patients in neutral way were also highly valued.

Interestingly, from this study it would also appear that skills are what should be taught. Naturally, enabling students to form their own opinion requires some knowledge as a basis. So certainly explanation of the conceptual frameworks and treatment modalities used in various CAM types is important to keep in the curriculum. But skills are rarely acquired in the lecture hall, so CAM education in medical schools should, in our opinion, also move into the small group sessions, discussion round tables, the bedside, and case-based clinical scenarios.

Conclusion

We would argue that a milestone on the way to the 12th EPA, to the ability to educate patients about disease management, should be the ability to respond to a patient seeking CAM treatment with a carefully considered response, which respects patient autonomy while simultaneously offering a truly educated, personal opinion (declared as such) about the CAM modality. This scenario also includes several other related, likely observable, and eventually entrustable activities and attributes: open-mindedness, the ability to assume different points of view (empathy), and academic curiosity, to name a few. Come to think of it, these are skills and attitudes to which increasing attention is being paid within the context of conventional medicine. As conventional medical curricula become more inclusive of complementary and alternative medicine, helping it reach the next generation of trainees, they may discover it helping them train the most patient-centred conventional medicine physicians for the future. How unconventional is that? (Table 1)

References

- Thomas-Hemak L, Palamaner Subash Shantha G, Gollamudi LR,Sheth J, Ebersole B, et al. (2015) Nurturing 21st century physician knowledge, skills and attitudes with medical home innovations: the Wright Center for Graduate Medical Education teaching health center curriculum experience. doi: 10.7717/peerj.766.

- AFMC Entrustable Professional Activities for the Transition from Medical School to Residency (2016) The AFMC EPA working group FMEC PG Transition Group Association of Faculties of Medicine of Canada.

- Prensky M (2017) Medical Education in, and for, an Exponentially Changing World”. Plenary lecture, Canadian Conference on Medical Education 2017, Winnipeg, Canada.

- Ruedy J, Kaufman DM, MacLeod H (1999) Alternative and complementary medicine in Canadian medical schools: a survey. CMAJ 160(6): 816-817.

- Taylor N and Blackwell A (2010) Complementary and Alternative Medicine Familiarization: What's happening in Medical Schools in Wales? Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 7(2): 265-269.

- Flaherty G, Fitzgibbon J, Cantillon P (2015) Attitudes of medical students toward the practice and teaching of integrative medicine. J Integr Med 13(6): 412-415.

- General Medical Council. Tomorrow's doctors; recommendations on undergraduate medical education 2015-02-13.

- Battacharya B (2000) Programs in the United States with complementary and alternative medicine education opportunities: an ongoing listing. J Altern Complement Med 6(1): 77-90.

- Nicolao M, Täuber MG, Heusser P (2010) How should complementary and alternative medicine be taught to medical students in Switzerland? A survey of medical experts and students. Med Teach 32(1): 50-55.