Tai Chi Research Review

Tiffany Field*

Fielding Graduate University, USA

Submission: October 22, 2016; Published: November 08, 2016

*Corresponding author: Tiffany Field, University of Miami/Miller School of Medicine, Fielding Graduate University, 2020 De La Vina St, Santa Barbara, CA 93105, USA, Email:tfield@med.miami.edu

How to cite this article: Tiffany F. Tai Chi Research Review. J Complement Med Alt Healthcare. 2016; 1(1): 555551. DOI:10.19080/JCMAH.2016.01.555551

Abstract

This paper is a review of empirical studies, systematic reviews and meta-analysis publications on tai chi from the last few years. The review includes demographics/prevalence of tai chi as a practice, bibliometric analyses of the tai chi publications and the use of tai chi for physical fitness and cognitive function. Also, studies are reviewed on tai chi effects on psychiatric, medical and immune conditions as well as aging problems. Most of the recent tai chi research has focused on balance problems in the elderly. The methods and results of those studies are briefly summarized along with their limitations and suggestions for future research. Basically, tai chi has been more effective than control and waitlist control conditions, although not always more effective than treatment comparison groups such as other forms of exercise. More randomized controlled studies are needed in which tai chi styles are compared to each other and tai chi is compared to active exercise groups. Having established the physical and mental health benefits of tai chi makes it ethically questionable to assign participants to inactive control groups. Shorter sessions should be investigated for cost-effectiveness and for daily practice. Multiple physical and physiological measures need to be added to the self-report research protocols and potential underlying mechanisms need to be further explored. In the interim, the studies reviewed here highlight the therapeutic effects of tai chi.

Tai Chi Research Review

This paper is a review of empirical studies, systematic reviews and meta-analyses on tai chi that have been published over the past few years (since our last review in 2012) [1]. The term tai chi was entered into PubMed and the selection criteria were empirical studies (single arm or randomized controlled studies) in which standard treatment, waitlist and treatment comparison groups were used as controls for the different style tai chi groups. Systematic reviews, bibliometric analyses and meta-analyses are also included. Exclusion criteria were case studies, qualitative studies, small sample pilot studies and research in which the assessors were not blind.

Brief summaries of papers are given on the demographics/prevalence of tai chi as a practice as well as bibliometric analyses of tai chi. Most of the studies reviewed here involve tai chi effects on psychiatric and medical conditions. These include student stress, cognitive and physical function; psychological conditions including insomnia, anxiety, depression, obesity-related depression and schizophrenia; cardiovascular and cardio respiratory conditions including hypertension and stroke; pain syndromes including low back pain, arthritis, fibromyalgia and spinal cord injuries; autoimmune conditions including type II diabetes and multiple sclerosis; immune conditions includingbreast cancer and lung cancer; and aging problems including anxiety disorder, fear of falling and balance, osteoporosis, knee osteoarthritis and Parkinson’s. Most of the recent tai chi research has focused on balance problems in the elderly. The methods and results of those studies are briefly summarized along with their limitations, potential underlying mechanisms and suggestions for future research.

Demographics

Tai chi is a martial art that is basically a slowed down version of karate movements and they are typically performed alone rather than in contact with a partner. Tai chi is practiced as 5 different styles with the Yang and Sun forms being the most popular in the U.S. and those that have been practiced in the studies summarized here [1,2]. The Yang style was created by Yang Luchan in the early 1800s in China and is the most widely practiced and easiest to learn, although there are 20 variations of this style with varying numbers of movements. The Sun style was created by Sun Lutang as a combination of Yang and other styles in about 1900 in China and is well-known for its smooth, flowing movements, although it is a more upright, less flowing style than the Yang style and lacks the more physically vigorous leaping and crouching movements of the other more difficult styles.

Tai chi movements typically lead to large vertical and mediolateral displacements of the body as compared to walking [2]. During movements called, for example, repulse monkey”and “wave hand in cloud”, the knees remain flexed while rangeof motion involves larger abduction and adduction of theknees than for walking. When tai chi practitioners and nonpractitionershave viewed videotapes of tai chi sequences, thepractitioners were able to discriminate the technical from theaesthetic components of the actions [3].

The exercise intensity of tai chi has been evaluated byoxygen consumption and heart rate [4]. These cardio respiratoryand energy expenditure measures suggest that tai chi is a lowintensity exercise. When the safety of tai chi was evaluated ina systematic review, only 33% of 153 eligible randomizedcontrolled trials (RCTs) included the reporting of adverse eventsand of those, only 12% overall noted a monitoring protocol foradverse events [5]. The adverse events reported were typicallyminor and basically musculoskeletal aches and pains typically inthe knees and back. These results are tentative and much of thereporting of adverse events has been limited and inconsistent.

Barriers as well as promoters for participation in tai chi haveincluded physical and mental health, time of day, socialization,accessibility and availability of teachers [6]. These data camefrom a study in which 87 lower socioeconomic older adults frommultiple ethnic backgrounds were interviewed before starting a16-week tai chi program. Another study measured adherence to a16-week tai chi program for multi-ethnic middle-aged and olderadults living in a low socioeconomic environment [7]. In thissample of 210 participants (mean age=68) greater adherencewas associated with older age, greater perceived stress, highereducation and higher scores on mental and physical scales. Incontrast, lower adherence was associated with higher baselineweekly physical activity.

A bibliometric analysis on 507 tai chi studies included8%systematic reviews, 50% randomized clinical trials, 18%randomized current controlled clinical studies and 23%single-arm (pre-post) studies [8]. The most frequent diseases/conditions studied were hypertension, diabetes, osteoarthritis,osteoporosis, breast cancer, heart failure, chronic obstructivepulmonary disease, coronary heart disease, schizophrenia anddepression [8]. The primary reason given for practicing tai chiwas for health promotion. The most common tai chi style wasthe Yang style, and typically tai chi was practiced 2 to 3 onehoursessions per week for 12 weeks. Tai chi was combinedwith other therapies including medications, physical therapiesand health education in 41 %of the studies and was practicedalone in 59% of them. At least 95% of the studies reportedpositive effects while 5% of the studies noted uncertain effects,and no serious adverse events were mentioned. These data arehighly suggestive, although only half the studies reviewed wererandomized clinical trials. This breakdown is consistent withthat of the current review.

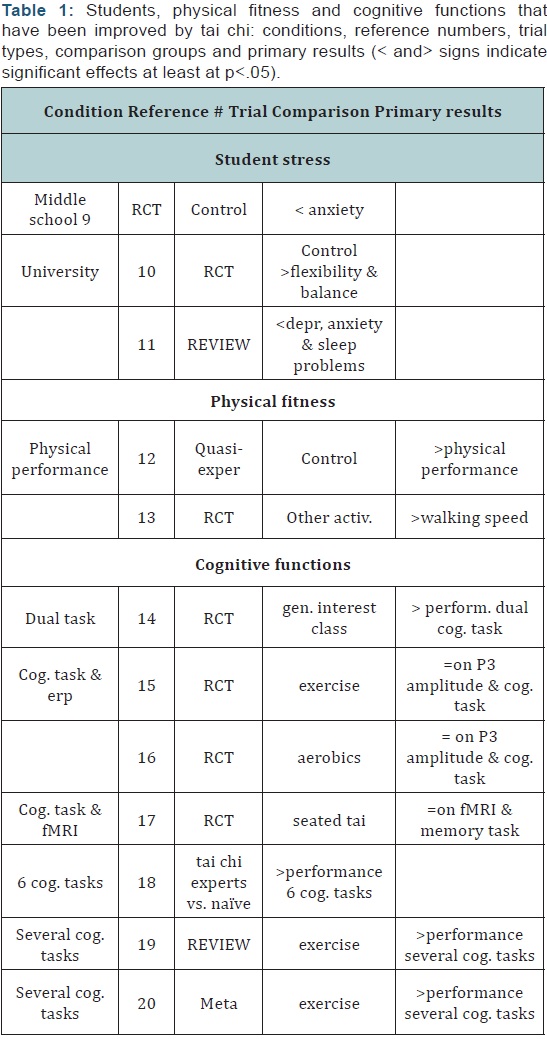

Student stress

A control group comparison, a randomized controlled trialand a systematic review were found in the recent literature ontai chi for student stress (Table 1). In the non-controlled groupcomparison 160 middle school students were given a one-yeartai chi program comprised of 60 minute sessions given five timesa week [9]. The tai chi group showed improvement in behavior,intellectual and school status and popularity as well as reducedanxiety as compared to the control group. In a study on collegestudents, 206 participants were randomly assigned to a 12-week tai chi group or to a control group that was instructed tocontinue their original activities [10]. The tai chi group showedsignificant improvements in flexibility on the site and reach testand on balance, and no adverse events were noted.

In a systematic review on tai chi with university studentsincluding 68 reports on a sample of 9,263 students, four primaryand eight secondary outcomes were noted [11]. These includedincreased flexibility, reduced depression symptoms, decreasedanxiety and improved interpersonal sensitivity. The secondaryoutcomes were improved lung capacity, better balance, fasterrunning time, and better quality sleep, reduced symptoms ofcompulsion, somatization and phobia and decreased hostility.The authors suggested that universities may provide tai chi as ameans of promoting the well-being of their students.

Cognitive and physical function

Several researchers have conducted studies on cognitive andphysical functions in various age groups. In a quasi-experimentaldesign with a non-equivalent comparison group, healthy andactive women were assigned to a tai chi program (twice a weekfor 8 weeks) or a control group [12]. By the end of the program thetai chi group was showing better physical performance. In a studywith an elderly sample, tai chi was provided twice per week forsix months and that group was compared to a control group whoparticipated in “other non-athletic activities” [13]. Assessmentsmade at three and six months suggested that the tai chi groupperformed better on the Mini-mental state examination, on gripstrength and on walking speed. In a randomized controlled studyolder women were randomly assigned to a 12-form Yang style taichi training or a general interest class control group [14]. At theend of 16 weeks the tai chi group showed superior performanceon a dual task cognitive exercise and better balance during thedual task condition.

In a study with a relatively complex design and measures,four groups were recruited including older adults performingendurance exercise, older adults practicing tai chi, older adultswith a sedentary lifestyle and young adults practicing tai chi[15]. The participants completed a task-switching exercise whileevent related potentials were recorded. Both the enduranceexercise and the tai chi group had larger P3 amplitudes(indicating greater attentiveness) and equivalent performanceon the cognitive task. In another event-related potential studytai chi participants were compared with aerobic exercise andsedentary control participants [16]. Both exercise groups hadlarger P3 amplitudes during a task switching test.

In a functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) study thatmeasures activation of different parts of the brain and functionalconnectivity between different parts of the brain, a tai chi groupwas compared to a quigong (seated tai chi) group [17]. Bothgroups showed significant improvement on a memory quotienttest, and their fMRIs showed increased functional connectivitybetween the hippocampus and the medial prefrontal cortex,suggesting that both forms of exercise may prevent memorydecline during the aging process. This, however, was the onlystudy that appeared in the recent literature that comparedstanding tai chi with sitting tai chi (qui gong), so it is unclear

whether standing or sitting tai chi is more effective. In a studycomparing tai chi experts with tai chi-naïve adults, the tai chiexperts showed better performance on six cognitive tasks [18].Typically, tai chi experts or tai chi practitioners have performedbetter than tai chi naive adults which are not surprising.

In a systematic review of nine studies including 632participants, the tai chi groups compared to “usual activitiesgroups” showed better performance on several cognitive tasks[19]. The problems with this review are that only five of thenine studies were randomized controlled trials and as many as12 different tests were used, making it difficult to measure theconsistency across studies.

In a meta-analysis, a large effect size was noted oncognitive tests when tai chi participants were compared withnonintervention controls, but only a moderate effect size wasfound when tai chi was compared with exercise controls [20].Again, only 11 of the 20 eligible studies were randomizedcontrolled trials. Nonetheless, the results highlight the positiveeffects of tai chi on cognitive functioning, at least in older adults.Younger adults have not been assessed for tai chi effects oncognitive functioning.

Psychological conditions

Several psychological conditions have been treated by taichi in the last few years including insomnia, anxiety, depression,obesity with depression symptoms and schizophrenia (Table2). Significantly fewer tai chi studies have been conducted onpsychological than physical conditions which is somewhatsurprising given that most of the studies have featured olderadult samples who would have psychological as well as physicalproblems.

Insomnia:For insomnia, tai chi was surprisingly ineffective.In one study, linear regression analysis suggested that theduration of practicing tai chi and the style of tai chi did notmake a significant contribution to sleep quality [21]. In thisnull finding study, however, most of the participants were goodsleepers which would reduce the likelihood of sleep beingaltered. In addition, it is surprising that the duration of practicingtai chi did not make a difference as longer-term practitionerstypically experience greater benefits. Different styles of tai chiare rarely compared, so the finding that different styles didnot have different effects needs to be replicated. Sleep effectshave been noted, in contrast, in a randomized controlled trialon older adults with chronic and primary insomnia [22]. Theseparticipants were randomly assigned to a cognitive behavioraltherapy group, a tai chi group or a sleep seminar educationcontrol group. Tai chi was associated with improvements in sleepquality, fatigue and depression as compared to the control group.However, the cognitive behavior therapy group performed betterthan both the tai chi and control groups in terms of the remissionof clinical insomnia. The superior effects for cognitive behaviortherapy may relate to the unusually long tai chi sessions (2hours) held weekly for four months having been too exhaustingfor these older adults.

Anxiety: Surprisingly, only one paper could be found inthe recent literature on tai chi for anxiety. This was a reviewpaper on 17 articles that met inclusion criteria with eight ofthem being from the US, two from Australia, two from Japan,two from Taiwan and one each from Canada, Spain and China[23]. Reduced anxiety was noted in at least 12 of the studiesreviewed. However, the authors noted several limitations ofthis body of research including that most of the studies werenon- randomized controlled trials that featured small samplesizes, non-standardized tai chi interventions and many differentoutcome measures.

Depression: Tai chi effects on depression have recentlybeen researched in the form of a survey and a couple metaanalyses.In the survey study, 529 Japanese tai chi practitionerswere given questionnaires on their training and their depressionsymptoms [24]. The prevalence of depressive symptoms was16%. The length of tai chi training was independently related tothe lesser prevalence of depressive symptoms. In a meta-analysisof randomized controlled trials on tai chi and depression, fourtrials with 203 participants met inclusion criteria [25]. Tai chisignificantly reduced depression symptoms as compared with wait-list control groups. In another systematic review andmeta-analysis, 37 randomized controlled trials and five quasiexperimentalstudies were included to assess the effects of tai chion depression, anxiety and psychological well-being [26]. Theconclusion of the meta-analysis was that tai chi had beneficialeffects on depression, anxiety, general stress management andexercise self-efficacy.

Obesity with depression symptoms: In a study on obesepeople with elevated depression symptoms, 213 participantswere randomly assigned to a 24-week tai chi intervention or awaitlist control group [27]. The tai chi group showed a significantdecrease in depression and stress and an increase in leg strength.These improvements were maintained for the tai chi groupover the second 12 weeks of follow-up. In another randomizedcontrolled study, only 26 obese women (a very small sample)were assigned to a 12-week tai chi intervention or controlgroup [28]. The tai chi exercises were combined with resistancetraining and a special diet, suggesting that the tai chi effects wereconfounded by the resistance training and diet. Although therewere no significant changes in body composition, the combinedintervention improved performance on the timed get up and gotest. In still another study on body composition, a Yang style taichi group was compared to an exercise group, with both groupsexercising 60 minutes three times per week for 12 weeks [29].The tai chi group showed a decrease in systolic blood pressure.However, the exercise group showed greater benefits includedincreases in basal metabolic rate, total body muscle mass, leanbody mass and bone mineral content and decreases in body massindex, body fat and diastolic pressure. These results perhaps are not surprising in that the tai chi group practiced with the samefrequency but with only 50 to 60% the intensity of that of theexercise group.

Schizophrenia: The management of schizophrenia by antipsychoticmedications often has severe side effects leading tothe use of complementary treatments like tai chi. In the onlyrecent study that could be found on schizophrenia, patientswere randomized to tai chi, exercise or waitlist control groups[30]. Both exercise groups received 12 weeks of the interventionand assessments were made at 3 and 6-month follow-ups. Bothexercise groups showed significant decreases in motor deficitsand increases in backward digit span, and the exercise groupalso showed fewer negative schizophrenic symptoms (such aslethargy and apathy)as well as fewer depression symptoms.

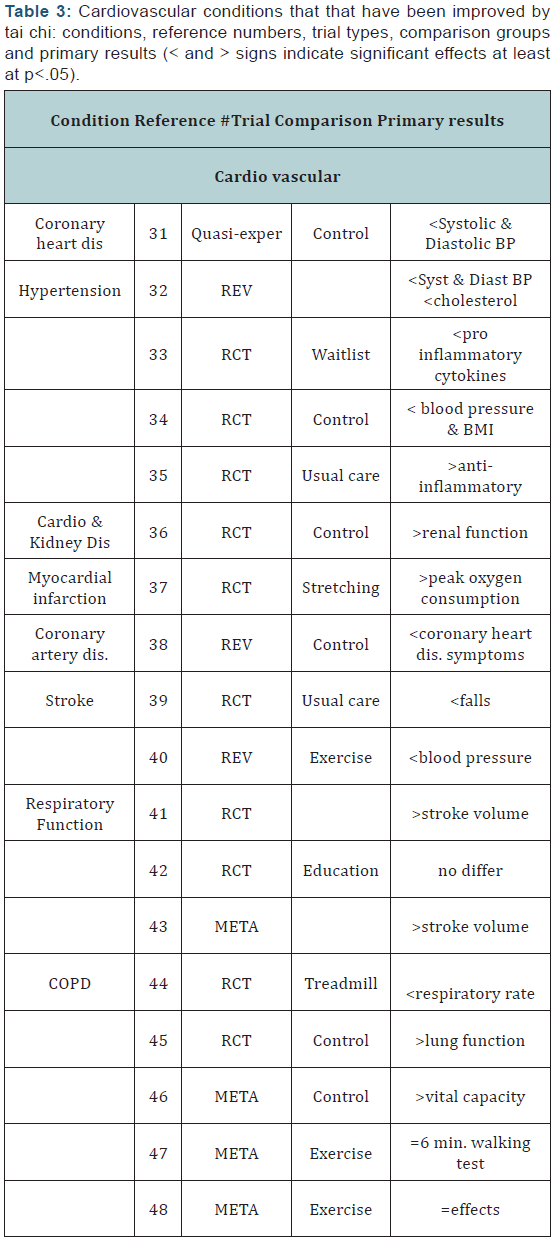

Cardiovascular/cardio respiratory disease

Eighteen randomized controlled trials, systematic reviewsand /or meta-analyses were found on tai chi with cardiovascular/cardio respiratory conditions (Table 3). These include coronaryheart disease risk factors, hypertension, cardiovascular andkidney disease, coronary artery disease, stroke and COPD.These conditions, next to balance in the elderly, were the mostfrequently studied conditions assessed for tai chi effects.

Coronary heart disease risk: In a quasi-experimentaldesign, a 16-week tai chi plus a weight loss program werecompared to a control group who were asked to maintain theirnormal lifestyle [31]. The tai chi group lost weight and improvedon body mass index, waist circumference, systolic blood pressure,diastolic blood pressure and sit and reach flexibility, suggesting that tai chi can ameliorate coronary heart disease risk.

Hypertension: In a systematic review on tai chi for primaryprevention of cardiovascular disease, 13 small randomized trials(1520 participants) not surprisingly showed that the durationand style of tai chi differed between studies [32]. And the samplesranged from people with borderline hypertension, hypertensionor hypertension combined with kidney disease. In addition,the reviewed studies featured non-treatment control groups.Despite these limitations, reductions were noted in systolicblood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, triglycerides and totalcholesterol. These findings are confirmatory of randomizedcontrol trials, but the considerable heterogeneity betweenstudies, the small samples and the risk for bias highlight the needfor higher-quality, longer-term trials.

In a randomized controlled trial that included a waitlistcontrol group, eight weeks of tai chi led to reduced cardiovascularrisk in middle-age women [33]. In this study the cardiovascularriskwomen who experienced tai chi had less fatigue and showeda down-regulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines includinginterferon gamma, tumor necrosis factor, and interleukins 4and 8. In addition, the women showed increased mindfulness,spiritual thoughts and behaviors and self-compassion.

In a randomized controlled study on adults with hypertension,blood pressure and body mass index were reduced, but metabolicsyndrome and lipid levels did not improve [34]. In an unusualdesign comparing hypertensive receiving tai chi, a hypertensiveusual care group and a healthy non-hypertensive group, lowdensity lipoprotein cholesterol levels decreased, high densitylipoprotein cholesterol levels decreased and both systolic anddiastolic blood pressure decreased by the end of the 12 weektreatment period [35]. A unique finding was an increase in nitricoxide, which is significant because of its anti-inflammatoryeffects. Further research is needed to confirm the nitric oxideeffects in a larger cohort.

Cardiovascular and kidney disease: To study the effectsof tai chi on renal and cardiac function of patients with chronickidney and cardiovascular diseases tai chi was provided for 30minutes 3 times a week for 12 weeks and tai chi was compared toan inactive control group [36]. At the end of the study, the tai chigroup had better glomerular filtration rate and left ventricularejection (both measures of renal function) and greater highdensitylipoprotein levels. In addition, the tai chi group had lowerheart rate, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure andtotal cholesterol, triglyceride and low density lipoprotein levels.Tai chi appeared to improve these functions by the regulation oflipid levels.

Myocardial infarction: Patients with myocardial infarctiontypically show decreased peak oxygen consumption [37]. Ina single-blind randomized controlled clinical trial, patientsassigned to the tai chi group participated in three weekly sessions of tai chi for 12 weeks while the control group participated in fullbodystretching exercises [37]. At the end of the study the tai chigroup showed a significant increase in peak oxygen consumptionwhile the control group showed a non significant decline.

Coronary artery disease: In an extensive review of 201studies on tai chi with patients experiencing coronary arterydisease, only three randomized controlled trials met criteria[38]. Each of these trials had a control group that practicedexercise training or received counseling for exercise. The resultssuggested that tai chi was an effective form of treatment forpatients with coronary artery disease. However, as the authorsnoted, the methodology in all of the studies was flawed and thesample sizes were small.

Stroke: Stroke is one of the leading causes of death in theworld [39]. A couple studies on stroke survivors show thepositive effects of tai chi. In a single blind randomized controlledtrial survivors of stroke were randomly assigned to a Yang style24-postures short-form tai chi, a strength and range of motionexercise group or a usual care group. The tai chi and exercisegroups attended one hour classes three times a week for 2weeks [39]. The tai chi participants had two thirds fewer fallsthan the exercise and care groups and both exercise groups hadsignificantly better aerobic endurance.

In a systematic review 36 eligible studies with a total of2393 participants were identified [40]. When the risk factorsfor stroke were considered, the analysis revealed that tai chi wascorrelated with lower body weight, body mass index, as well aslower systolic and diastolic blood pressure and lower low densitylipoprotein levels even for less than a half year of intervention.However, when tai chi was compared to similar exercises, theprimary effect was only lower blood pressure.

Cardio respiratory diseases

Turning to cardio respiratory diseases, positive effects of taichi on respiratory and cardiovascular function were observedfollowing 12 months of tai chi [41]. At the end of the studythe results showed that stroke volume was increased, ejectionfraction was improved as was vital capacity and heart rate wasdecreased. One of the potential underlying mechanisms for taichi’s positive effects on cardio respiratory functions is that taichi focuses on the coordination between respiration and bodymovements [42]. In the aging process apparently respirationaffects postural sway, and by tai chi improving respiratoryfunction it can also improve postural control. This relationshipwas shown in a study on a 12 week tai chi intervention versusan educational control group [42]. While the tai chi training didnot alter standing postural control or respiration, the couplingbetween respiration and postural control was reduced. For somereason as in many other tai chi studies, the sample sizes for thetwo groups were unequal which may reflect a self-selection biasand which may have contributed to these null findings.

In a systematic review and meta-analysis 20 studies with1868 participants suggested that tai chi had positive effects onthe majority of cardio function outcomes [43].These includedsystolic and diastolic blood pressure, heart rate, stroke volume,cardio output, lung capacity, cardio respiratory endurance andstair test index.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

COPD has also benefited from tai chi. In a randomizedcontrolled study comparing tai chi with treadmill exercise,the respiratory rate during tai chi was significantly lowerthan during treadmill exercise even though the mean valuesof oxygen uptake did not differ across the two exercises [44].In another randomized controlled study patients with COPDwere assigned to either a control group or a tai chi group [45].Lung function parameters and diaphragm strength parameterswere significantly increased in participants who successfullycompleted the six-month tai chi program. In a systematic reviewand meta-analysis on the effects of tai chi on chronic obstructivepulmonary disease, 15 articles involving 1354 participants metcriteria [46]. Compared to an inactive control group tai chi wasmore effective in improving exercise on six - minute walking test,on forced expiratory volume in the first second and on forcedvital capacity. The tai chi group also scored better on the dyspneascore, fatigue score and total score of the Chronic RespiratoryDisease Questionnaire. However, once again, it is not surprisingthat tai chi effects would be more positive than those of aninactive control group. Future studies need to compare differentstyles of tai chi or at least compare tai chi with active exercisegroups to determine reliable treatment effects.

To address that question, a systematic review and metaanalysisstudy included both exercise and non-exercisecomparison groups and the tai chi group once again performedbetter than the non-exercise group on the chronic respiratorydisease questionnaire [47]. However, when compared withthe physical exercise group, the tai chi group showed inferiorperformance on that scale, even though the groups did notdiffer on the 6 minute walking test. When a systematic reviewand meta-analysis was performed on 18 tai chi studies forcardiovascular or cardio respiratory conditions, tai chi was nomore effective than other forms of exercise [48]. Given the stressunderlying cardiovascular and cardio respiratory conditions, itis somewhat surprising that tai chi was not more effective thanother forms of exercise because its meditative component andthe need to be totally concentrated on the tai chi form (calledfocused mindfulness) would be a distract or from stress.

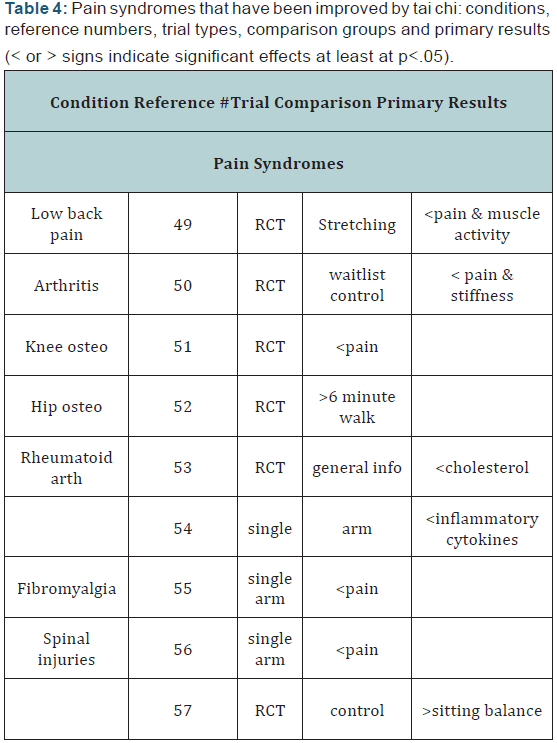

Pain syndromes

Just as for other forms of complementary therapy such asyoga and massage, pain syndromes have been frequently studiedfor tai chi effects. Briefly reviewed here are tai chi studies onlow back pain, arthritis, osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis,fibromyalgia and spinal cord injury pain (Table 4).

Low back pain: In a study on low back pain 40 males withlow back pain were randomly assigned to a tai chi group or astretching group [49]. The exercises were performed for onehour three times per week for four weeks. Wireless surfaceelectromyography was used to measure muscle activity and avisual analog scale was used to measure pain. The decrease inboth muscle activity and in pain was greater for the tai chi groupthan the stretching group.

Arthritis: In an assessment of the Arthritis Foundation taichi program, those with arthritis were randomly to the tai chigroup or a waitlist control group [50]. Following this eight weekprogram balance was improved. At one year improvements inpain, fatigue and stiffness were noted, suggesting long-termeffects in at least 30% of those who continued tai chi practicefollowing the end of the program.

Knee osteoarthritis: A systematic review of studies on taichi for knee osteoarthritis used the following selection criteria:1) randomized controlled clinical trial; 2) patients with kneeosteoarthritis; 3) tai chi exercise; and 4) studies published inEnglish or Chinese [51]. Tai chi was an effective way of relievingpain and improving physical function for those with kneeosteoarthritis. However, the randomized controlled trials did notinclude exercise comparison groups.

Hip osteoarthritis: Individuals with hip osteoarthritis wererandomly assigned to a tai chi or a control group [52]. After sixweeks of the program the tai chi group walked farther in the6-minute walk test and they were faster in the get up and go test.

Rheumatoid arthritis: Given that rheumatoid arthritisis a risk factor for cardiovascular disease, several measures ofthat risk were taken in a tai chi study on rheumatoid arthritis[53]. Patients were randomly assigned to either a tai chi groupreceiving once a week sessions for 3 months or a control groupwho received general information about the benefits of exercise.Endothelial function increased and arterial stiffness andcholesterol decreased in the tai chi group. Surprisingly, pain wasnot assessed in this study. Arthritis-associated pain is generallyassociated with inflammatory mediators such as cytokines [54].Following only one hour of practice by tai chi practitioners,plasma levels of IL-1a and IL-12 were decreased. This single arm,small sample pilot study needs to be replicated.

Fibromyalgia A low to moderate intensity tai chi programwith 3 sessions per week for 12 weeks was offered to 36 patients(29 women) [55]. Immediate post-session reductions in painwere noted. However, pain was assessed by a visual analoguescale in this single arm study. And, surprisingly, no other recenttai chi for fibromyalgia studies could be found.

Spinal cord injury pain: Seated tai chi has been used withthose who have spinal cord injuries. In a single arm study, 26participants were enrolled for a 12 week seated tai chi courseconsisting of weekly sessions [56]. After each session thepatients reported less pain, better sense of emotional wellbeing,mental distraction, physical well-being and a sense ofspiritual connection. However, attrition was high with only nineparticipants completing half of the 12 sessions and once againthis was not a randomized controlled study with a comparisongroup to validate the effects of tai chi on spinal cord injury pain.However, this is a rare example of the use of seated tai chi.

In another seated tai chi study, patients with spinal cordinjuries were given 90 minute sessions two times a week for12 weeks or assigned to a control group [57]. At the end of theintervention, the seated tai chi group showed improved dynamicsitting balance and greater hand grip strength. However, thegroups did not differ on quality of life measures. Once again, thisis a small sample and the groups were not randomly assigned.Further, seated tai chi is rarely practiced, although it wouldclearly be the tai chi of choice for patients who are immobilizedwith spinal cord injuries.

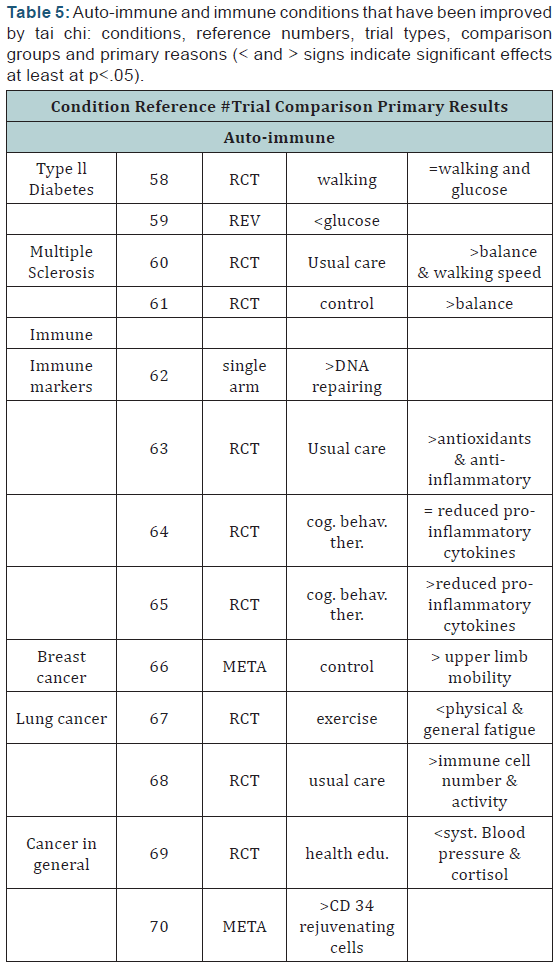

Autoimmune conditions

Diabetes and multiple sclerosis were the only autoimmuneconditions in the recent tai chi literature (Table 5). Theseincluded a randomized controlled trial and a systematic reviewon diabetes and two randomized controlled trials on multiplesclerosis.

Diabetes: In a study on Hong Kong Chinese adults 374middle-age diabetes patients were randomly assigned to a 12week training 45 minutes per day, five days per week of tai chior self -paced walking or a control group [58]. Both exercisegroups experienced moderate weight loss and significantlyimproved their waist circumference and fasting blood glucose.A systematic review revealed mixed findings with four RCTsthat compared various types of exercise and tai chi [59]. Thatmeta-analysis failed to show group differences on fasting bloodglucose which was not surprising in that tai chi and exercisefrequently have similar effects. However, surprisingly, the metaanalysisof the five RCTs that compared tai chi with antidiabeticmedication showed more favorable effects of tai chi thanmedication on fasting blood glucose. The authors concluded thatthese tai chi effects on fasting blood glucose in diabetes clearlyneed replication studies.

Multiple sclerosis: Individuals suffering from multiple sclerosis have experienced many problems including balance,mobility, fatigue and depression [60]. A sample of 32 multiplesclerosis patients randomly assigned to a tai chi groupparticipated in two weekly sessions of 90 minutes duration forsix months while the comparison group received treatment asusual [60]. Following the intervention, the tai chi group showedgreater balance and coordination, less depression, and theirquality of life improved. In another randomized controlled study,36 women with multiple sclerosis were randomly assigned to atai chi or a control group [61]. After 12 weeks of twice a weekYang style tai chi sessions, the tai chi group had better balancescores on the Berg balance scale. Unfortunately this was assessedby self-report rather than objectively observed.

Immune conditions

Several recent studies were found on tai chi effects on immunemarkers and conditions (Table 5). The marker studies assessedantioxidants, anti-inflammatory cells, cytokines and cancer cells.Of the immune conditions, breast cancer has received the mostattention, although a couple studies were found on lung canceras well as cancer survivors in general.

Immune markers: In a single arm study, the 24-formsimplified tai chi was practiced five times weekly for 12 weeksto determine the effects of tai chi on antioxidant capacity andDNA repairing [62]. The young Chinese females in this studyshowed an improved oxidative stress response and increasedDNA repairing. These results are promising although limitedbecause of the small sample size and the single arm design.In a randomized controlled study, 71 sedentary volunteerswith periodontal disease were randomly assigned to a taichi or treatment as usual group [63]. Tai chi was practicedfive days a week for a period of six months. Antioxidants andanti-inflammatory cytokines increased and were linked toimprovement of periodontal disease in the tai chi group. It isnot clear that these tai chi effects would have resulted from acomparison between tai chi and an active exercise group.

In another randomized controlled trial on tai chi and immunemarkers, 123 older adults with insomnia were randomlyassigned to cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), tai chi or asleepseminar control group for two hour sessions weekly over a fourmonthperiod [64]. Given that sleep disturbances are associatedwith inflammation; several pro-inflammatory cytokines weremeasured. Both the CBT and tai chi groups experienced reducedlevels of C-reactive protein, pro-inflammatory cytokines and proinflammatorygene expression. These results were surprisinginasmuch as CBT is a physically inactive therapy. However, apotential underlying mechanism common to CBT and tai chi maybe the facilitation of sleep which would in turn improve immunefunction in both groups.

Breast cancer: The same group of researchers who studiedan insomnia group also assessed a group of 90 breast cancersurvivors with insomnia using similar measures [65]. In this randomized controlled trial the breast cancer survivors withinsomnia were randomly assigned to a tai chi or a CBT forinsomnia group. In this study the C-reactive protein levels did notchange, but the levels of interleukin -6 (IL -6) and tumor necrosisfactor (TNF) were reduced following tai chi but not followingCBT for insomnia. The genes encoding pro-inflammatorymediators were also reduced in the tai chi versus the CBT forinsomnia group. It is not clear why this research group was ableto document immune changes following CBT for insomnia in thegroup that had late - life insomnia but no changes for the breastcancer survivors with insomnia. This inconsistency may relateto the intervention being longer in the insomnia - alone study,i.e. one month longer for the CBT for insomnia treatment to takeeffect, or it may simply be that the immune system was morecompromised in the breast cancer survivors and thereby lessreactive to the CBT treatment and more reactive to the greateractivity of tai chi. The underlying mechanism for the CBT and taichi effects in the insomnia alone study may be sleep mediatedwhile the tai chi effects on the breast cancer victims may havebeen mediated by activity increasing stimulation of pressurereceptors in turn enhancing vagal activity resulting in lowerlevels of cortisol and pro-inflammatory cells.

In a systematic review/meta-analysis study, nine randomizedcontrolled trials including 322 breast cancer patients met criteria[66]. In these trials, comparisons between tai chi and controltherapies yielded only changes in upper limb functional mobility.These included increased handgrip dynamometer strength andlimb elbow flexion. No differences were noted for pain, IL - 6,physical, social or emotional well-being. It is surprising that IL -6was the only immune measure common across the studies thatmet criteria.

Lung cancer: In a randomized controlled trial on tai chieffects on patients with lung cancer undergoing chemotherapy,tai chi was compared with low impact exercise [67]. The groupspracticed every other day for one hour for 12 weeks. At six andat 12 weeks the tai chi group had lower physical fatigue andgeneral fatigue scores, although no differences were noted on theemotional subscale. In another randomized controlled study ontai chi effects on cell functions in lung cancer patients, tai chi wassimply compared with a treatment as usual control group [68].In this study, Tai chi 24 - form was practiced for 60 minutes threetimes a week for 16 weeks. Immune cell number and immunecell activity increased in the tai chi group as compared to thecontrol group. Again this finding may result from comparing anactive group (tai chi) with an inactive group (treatment as usual),highlighting the importance of comparing active treatmentgroups to determine the efficacy of tai chi.

Cancer in general In another randomized controlled trialof tai chi effects on cancer, specifically senior female cancersurvivors, tai chi was compared to a health education class [69].Tai chi was practiced and the health education classes were heldfor 60 minutes three times a week for 12 weeks. The tai chi group had significantly lower systolic blood pressure and cortisollevels at the end of the study. There were, however, no changes ininflammatory cytokines.

In a systematic review/meta-- analysis study on tai chi effectson cancer patients in general, 13 randomized controlled trialswith 592 participants were included [70]. This study not onlyconfirmed the decrease in cortisol levels noted in the previousstudy, but also showed improved quality of life measures, lessfatigue and improved immune function. These authors cautiouslynoted an increase in CD 34 rejuvenating cells in the tai chi group.They suggested that their data were limited by the number ofstudies they identified and the by the high risk for bias in thestudies included in their meta-analysis.

Aging problems

Most of the recent tai chi studies involve aging problems.Those include empirical studies, systematic reviews and metaanalyseson antiaging cells, anxiety, fear of falling and balanceproblems, physical fitness, osteoporosis, pain; Parkinson’s andseated tai chi (Table 6).

Antiaging cells: In a retrospective cross-sectional study,rejuvenating and anti-aging cells were studied in a tai chi versusa brisk walking versus a no exercise habit group [71]. The CD 34rejuvenating cells were greater in the tai chi group than in theno exercise group, but there were no differences between the taichi and the brisk walking groups. The lack of difference betweenthe tai chi and exercise group was not surprising given that thereare often no differential effects when tai chi is compared to otherforms of exercise. These data, while consistent with the previousmeta-analysis [70], need to be replicated in a larger sample ina prospective random assignment design as many potentialbaseline differences including motivational factors could accountfor these effects.

Anxiety Disorder: In a randomized controlled study, 32elderly patients with anxiety disorder were randomly assignedto a tai chi plus drug therapy group versus a drug therapy alonegroup [72]. After 45 days of tai chi, that group had improvedsignificantly on depression scores and had a recurrence rateof 9% versus 43% in the control group. These data are notsurprising given that the exercise of tai chi would be expected tolower anxiety and underlying anxiety hormones such as cortisol.In addition the exercise of tai chi would be expected to increaseserotonin levels which have anti-anxiety affects. This studymight be replicated in a larger sample and with the addition ofother more objective measures of depression such as cortisoland serotonin levels.

Fear of falling: Fear of falling and balance are the mostcommonly studied problems for the aging in the recent tai chiliterature. In a randomized controlled study 122 elderly peoplewere randomly assigned to either a tai chi or tai chi plus CBTgroup [73]. Only the tai chi group experienced less fear offalling. For fear of falling the authors concluded that tai chi maybe sufficient and more cost-effective. In another randomizedcontrolled trial, home - based tai chi training was comparedto lower extremity training in elderly who had fall - related emergency room visits at least six months before being recruitedfor the study [74]. After a six month intervention, the tai chigroup was less likely to experience any falls, had a longer time tothe first fall and a lower number of “fallers “as compared to thelower extremity training group.

Balance: Several dual-task studies have been conductedto assess the ability to maintain balance while performing acognitive task, i.e. assessing balance while paying attention tosomething else. This is being assessed because many falls havebeen related to elderly individuals concentrating on somethingelse, getting distracted and losing their balance. In one studyon 10 elderly tai chi practitioners and 10 age matched nonpractitioners,the participants were asked to shift their weightto reach a target with and without performing the cognitivetask of counting backwards [75]. The Tai chi practitioners hadshorter reaction times and faster movements than the non-taichi practitioners. In a similar dual-task study, tai chi expertsand non-experts were compared on their walking time whilethey performed serial subtractions [76]. Walking or stride timevariability was lower in the tai chi expert group. Walking timevariability has been considered a potential mediator of the riskfor falling. Although comparisons of tai chi practitioners versusnon-practitioners would be expected to reveal greater effects forthe practitioners given their greater activity levels, but the twogroups may also differ on baseline motivation, physical fitnessand other variables, making their comparison tenuous at best.

Another way of testing balance is the sway paths both to eachside and from the front to the back. In a sway path balance study,a tai chi group was compared to a no regular exercise group[77]. The tai chi group showed shorter sway paths both forwardand back and to each side after 24 weeks of tai chi. Some of thesway path balance can be explained by ankle proprioceptionand lower extremity muscle strength [78]. In one study, a tai chigroup who had practiced for 10 years on average showed betterbalance, ankle proprioception and muscle strength of the lowerextremities than a group who did not practice tai chi [78].

In several balance studies, tai chi has been compared to otherforms of exercise. In one study tai chi was compared to ballroomdancing [79]. In this randomized controlled trial, the tai chigroup had a lower sway velocity both with open and with closedeyes on a firm surface as well as a foam surface. The tai chi groupalso had faster walking speed and shorter times moving from asitting to a standing position with less sway in the final standingposition. In another study, tai chi was compared to regularexercise that was performed three times a week for 12 weeks[80]. Both exercise groups showed better results on dynamicbalance assessments. However, the tai chi group showed betterperformance on the single leg stance eyes open task and on asurvey of activities and fear of falling scale.

In a tai chi versus yoga versus standard balance training,the three different groups practiced for 12 weeks, and on the gold standard measures including postural sway and posturalstability, all three groups showed similar improvement [81]. Inanother study comparing tai chi and yoga, following a 14 weekprogram, no significant differences were noted between thegroups in the incidence of falls [82]. In a meta-analysis of sevenrandomized controlled trials including 1088 participants, tai chiwas compared with other interventions and was shown to havesignificantly shorter time on get up and go, prolonged time onsingle leg stand and improved balance [83]. Other meta-analyseson a greater number of randomized controlled trials need to beconducted to confirm these data.

Physical Fitness: Although not as frequently studied asbalance in elderly people, there are at least a few studies onphysical fitness and muscle strength following tai chi. Forexample, in a 16 week tai chi program, physical fitness wasassessed in older adults with and without previous tai chiexperience [84]. The tai chi group was comprised of participantswho had practiced for more than a year. When this group wascompared to an inexperienced group, experienced practitionershad higher ratings on physical fitness tests, as would be expected.However, when the inexperienced group was given two one-hour sessions per week of Yang style tai chi for 16 weeks, theyshowed significant improvements on all measures of physicalfitness. In another study, physical fitness included measures oflower limb muscle strength, bone mineral density and balance[85]. In this study elderly women were randomly assigned to atai chi group, a dance group and a walking group, and they wereasked to do the exercise once a day for 40 minutes for 12 months.Physical fitness was assessed at four, eight and 12 months. Afterfour months the dance group and walking group were showingbetter physical fitness than the tai chi group. At eight months allthree groups were equivalent, but at 12 months the tai chi groupshowed a greater improvement than the dance and walking groups, suggesting that longer-term tai chi programs have longerterm effects on physical fitness than the comparison dance andwalking groups. It is not clear, however, the degree to whichthese groups were matched on exercise intensity.

Muscle strength: In a study on muscle strength of thelower extremities in the elderly, long-term tai chi practitionerswere compared to those who did not practice tai chi [86]. Thestrength of several muscle groups including the quadriceps andhamstrings was greater in the tai chi practitioner than the nonpractitionergroup. Further, muscle strength and the duration oftai chi practice were significantly correlated. Although musclestrength is typically measured in the lower extremities followingtai chi, at least two studies have assessed upper limb strength. Inone of these studies, elderly participants were randomly assignedto a tai chi group that practiced for six months as compared to acontrol group who participated in other non-athletic activities[87]. After 3 months there was no difference between the groupson one leg standing time with eyes open. However, grip strengthwas greater and both the five minute fast walking speed and 10 minute normal walking speed were significantly greater in thetai chi group. In another study, the researchers used resistancetraining with the upper extremities in conjunction with tai chias compared to a group that did not receive tai chi or resistanceexercise [88]. Therabands (wide rubber strips) were used for theresistance training which was held for 60 minutes twice weeklyfor a period of 16 weeks. After this training, the interventiongroup showed a significant increase in muscle strength in bothupper and lower extremities. These effects are not surprisinginasmuch as the tai chi exercise would be expected to strengthenthe lower limbs while the theraband resistance training isfocused on increasing upper limb strength.

Osteoporosis: Osteoporosis (bone loss) is common amongthe elderly. In this literature search at least one randomizedcontrolled trial and one systematic review on osteoporosis werelocated. In the randomized controlled trial, 119 postmenopausalwomen were randomly assigned to a Yang style tai chi resistancetraining, a traditional tai chi or a routine activity group [89].Although the routine activity group had lower L2 - L4 bonedensity, neither the tai chi nor the resistance training groupsexperienced bone loss. In a recent systematic review onosteoporosis, only four valid studies could be found that eitherused a randomized clinical trial or controlled clinical trial [90].The only positive effects were for balance, muscle strength andquality of life, highlighting the need for more research on tai chieffects on bone loss itself.

Knee osteoarthritis pain: For knee osteoarthritis the onlyrecent tai chi papers featured a randomized controlled trialand a review. In the randomized controlled trial, older adultswere recruited from eight study sites and then the sites wererandomly assigned to participate in either a 20 week Sun - styletai chi or an education program [91]. Not surprisingly, the activetai chi groups experienced a greater reduction in pain than theinactive education group. In our recent review of Tai chi forknee osteoarthritis, pain was assessed by the WOMAC scale inmost of the studies reviewed [92]. Range of motion and rangeof motion pain are highly affected by knee osteoarthritis, butthose measures were not assessed in most of the studies. Thiswas surprising given that tai chi predominantly exercises thehamstrings and quadriceps which are both involved in flexionand extension of the knee. Range of motion and range of motionpain would need to be measured to determine the primaryeffects of tai chi on knee osteoarthritis.

Parkinson’s: Since elderly people are frequently affected byParkinson’s, it is not surprising that as many as three randomizedcontrolled trials and three meta-analyses were found in therecent literature. In one of the randomized controlled trials, thetai chi group received 24 - form Yang style tai chi exercise for60 minutes three times a week for 12 weeks [93]. This tai chigroup improved their balance and decreased their falling, butno change occurred on the Parkinson’s disease Rating Scale, suggesting that their Parkinson’s symptoms were not decreased.However when tai chi was compared to resistance training andstretching in another randomized controlled trial, the tai chiparticipants reported significantly better improvement on theParkinson’s disease Questionnaire and their scores on that scalewere significantly correlated with their scores on the Parkinson’sdisease Rating Scale [94]. The authors also noted that the patientreportedoutcomes were associated with a greater probability ofcontinued exercise behavior in the tai chi group versus the othergroups, suggesting that there was greater adherence by the taichi group. In still another randomized controlled trial, tai chi wascompared to multimodal exercise training and the groups wereassessed after 12 weeks of the program [95]. In this study, bothgroups improved on movements, balance and on Parkinson’sDisease Rating Scale-motor examination scores.

In a meta-analysis on tai chi with Parkinson’s disease,seven randomized controlled trials that were eligible showedthat tai chi had beneficial effects on motor function, balanceand functional mobility but not on gate velocity, step length orgate endurance [96]. However, when tai chi was compared withother active therapies, better effects of tai chi were only notedfor balance. In another meta-analysis, the aggregated resultsof 9 studies favored tai chi on improving motor function andbalance [97]. Once again, gate velocity, stride length and qualityof life were not affected. However, the authors interpreted thesefindings cautiously because of the small treatment effects, themethodological flaws of the eligible studies and the insufficientfollow-up. In still another meta-analysis, 10 trials on tai chiplus medications for Parkinson’s showed improvements on theParkinson’s Disease Rating Scale, on the Berg balance scale,functional reach tests, timed get up and go test, stride lengthand health-related quality of life [98]. The tai chi alone group,however, was only more effective for balance and mobilityoutcomes.

Seated tai chi: Seated tai chi has been used to improve sittingbalance and for individuals in wheelchairs. In a randomizedcontrolled study on seated tai chi, sitting balance and eye handcoordination were assessed [99]. In this study, the tai chi groupwas compared to an exercise group who underwent threemonths of training for a total of 36 sessions including one hoursessions three times per week. The tai chi group improved onweight shifting while sitting and on maximum reaching distancefrom the seated position. In another seated tai chi randomizedcontrolled study, older people in wheelchairs were randomlyassigned to a group receiving seated tai chi versus a groupengaging in their usual activity [100]. The tai chi group had 40minutes of seated tai chi three times a week for 26 weeks. Theseated tai chi group had lower depression scores and higherquality of life scores including general health, physical health,psychological health, and social relations. Unfortunately, onceagain, only self-report measures were taken.

Potential underlying mechanisms for tai chi effects

Studies have been conducted to determine the underlyingphysiological mechanisms for tai chi effects. Recently these haveincluded research on fMRI’s and on vagal activity.

FMRI studies: In an fMRI study for older individualsincluding 22 experienced practitioners and 18 tai chi naïvecontrols, fMRI and attention behavior tests were conducted[101]. The tai chi practitioners as compared to the inexperiencedgroup had greater functional homogeneity in the right posteriorcentralgyrus and less functional homogeneity in the leftanterior cingulate cortex gyrus both of which predicted betterperformance on attention behavior tests. As the authors noted,these findings can inform our understanding of the effects of taichi on cognition.

Vagal activity studies: At least three recent vagal activitystudies suggest increased vagal activity as a potential underlyingmechanism for the effects of tai chi. In one study, 25 tai chipractitioners were compared with 25 sedentary controlparticipants on heart rate variability (vagal activity) [102].The tai chi practitioners had greater high frequency powerand lower low-frequency power than the controls, suggestinggreater vagal modulation in the practitioners. Another similarcomparison between tai chi practitioners with approximately20 years’ experience and controls matched by age, sex andeducation also suggested increased vagal activity for the taichi group and greater balance between parasympathetic andsympathetic activity during tai chi [103]. Vagal activity hasbeen noted to increase even after only five minutes of tai chiexercise by inexperienced individuals [104]. In this study,during the fourth and fifth minutes of tai chi exercise increasedhigh-frequency power and decreased low-frequency powerwere noted. It is not clear, however, whether these effects weretransient or maintained as the monitoring of vagal activity wastoo short. It would also be important to compare the effects oftai chi and other forms of exercise on vagal activity. For example,vagal activity has been notably greater in yoga practitioners andalso increases following yoga sessions [105]. This would not be surprising given that on many other measures tai chi and otherforms of exercise have similar effects. Just as we have notedthat increased vagal activity is dependent on the stimulationof pressure receptors, tai chi would involve the stimulation ofpressure receptors, at least in the feet [106].

Limitations of studies and future directions

Many of the limitations and confounds we reviewed in our2012 review paper are still problems for the tai chi literature [1].One of the problems is that tai chi is a combination of foot andarm movements, breathing and deep concentration. Although thefoot movements predominate most tai chi sessions, making taichi a physical exercise, it is difficult to separate the effects of thefoot and arm movements, the breathing and the meditation. It isa low intensity exercise in part because it involves concentration and a slowing of nervous system activity which may be thereason that it often has lesser effects than an active exercisegroup. The increased vagal activity noted for the foot and the armmovements and the meditation combined suggests that thosedifferent components may have additive effects, although theyhave not been studied for their separate effects. More detaileddescriptions of these components are needed in order for thesestudies to be replicated.

Another problem is that many different tai chi styles, e.g.Sun style and Yang style tai chi, have been tried with differentconditions. It is possible that a specific type of tai chi may bemore beneficial for a specific condition, suggesting the use ofdifferent tai chi styles as treatment comparison groups ratherthan using other types of exercise as treatment comparisongroups. Although the two most popular styles, Yang and Sunstyles have not been compared in one study, they would appearto have similar effects even though the Yang style is reputedlyeasier to learn.

The sessions are also highly variable including individualversus group practice, the length of the practice (20-90 minutes),the frequency of classes (daily, weekly) and the duration ofintervention (weeks, months). The samples are also variable, withsome studies grouping beginners with long-term practitionerseven though these participants likely differ at baseline. Longtermpractitioners may be in better condition at baseline andmore motivated to routinely practice. Although randomizedcontrolled designs are increasingly being used, many of therecent studies reviewed here are single - arm, pre-post studies orcomparisons between tai chi and inactive control groups. Thosecomparisons have typically yielded positive effects for the taichi group, but when tai chi was compared to an exercise group,the groups typically did not differ and sometimes the exercisegroup experienced more positive effects. Nonetheless, tai chimay remain the exercise of choice for more fragile people likepregnant women and older adults because it is a less intenseform of exercise. Notably absent from the literature are tai chieffects on different cultures, different age groups and any gendereffects. Although it appears to be practiced more frequently bythe elderly in China, the practice has been rapidly growing indifferent cultures and different age groups, so those comparisons would be possible.

Many of the studies also used self - report measures whichare not considered as reliable as the more objective observationmeasures. Physical and physiological measures that are moreobjective than self-report measures have rarely been used, e.g.body mass index, blood pressure and cortisol.

Conclusion

In conclusion, future research should use randomizedcontrolled trials in which different tai chi styles are compared,and shorter sessions might help the participants more readilylearn the forms. Multiple physical and physiological measures need to be added to the self - report protocols, and potentialunderlying mechanisms need to be further explored. Despitethese methodological problems, the studies reviewed herehighlight the therapeutic effects of tai chi, an old practice thathas fortunately come to us from Asia and one that will hopefullybecome as popular as yoga in our country. For many practitionerslike pregnant women and elderly people, it may be the preferredform of exercise for both its important low intensity andbalancing features.

Summary

Most of the studies reviewed here involved tai chi effects onpsychiatric, medical and immune conditions and aging problems.Most of the recent research has been on the elderly with a focuson balance problems. The methods and results of those studieswere briefly summarized along with their limitations andsuggestions for future research. Basically tai chi has been moreeffective than control and waitlist control conditions, althoughnot always more effective than treatment comparison groupssuch as other forms of exercise. More randomized controlledstudies are needed in which tai chi is compared to other forms oftai chi or at least to active exercise groups. Having established thephysical and mental health benefits of tai chi makes it ethicallyquestionable to assign participants to inactive control groups.Shorter sessions should be investigated for cost-effectiveness andfor daily practice. Multiple physical and physiological measuresneed to be added to the self-report research protocols, andpotential underlying mechanisms need to be further explored. Inthe interim, the studies reviewed here highlight the therapeuticeffects of tai chi.

References

- Field T (2011) Tai Chi Review. Complement Ther Clin Pract 17(3): 141-146.

- Law NY, Li JX (2014) The temporospatial and kinematic characteristicsof typical Tai Chi movements: Repulse Monkey and Wave-hand inCloud. Res Sports Med 22(2): 111-123.

- Zamparo P, Zorzi E, Marcantoni S, Cesari P (2015) Is beauty in the eyesof the beholder? Aesthetic quality versus technical skill in movementevaluation of Tai Chi. PLoS One 10(6): e0128357.

- Smith LL, Wherry SJ, Larkey LK, Ainsworth BE, Swan PD (2015) Energyexpenditure and cardiovascular responses to Tai Chi Easy. ComplementTher Med 23: 802-805.

- Wayne PM, Berkowitz DL, Litrownik DE, Buring JE, Yeh GY (2014) Whatdo we really know about the safety of Tai Chi? A systematic review ofadverse event reports in randomized trials. Arch Phys Med Rehabil95(12): 2470-2483.

- Manson JD, Tamim H, Baker J (2015) Barriers and promoters forenrollment to a community-based Tai Chi program for older, lowincomeand ethnically diverse adults. J Appl Gerontol [Epub ahead ofprint].

- Shah S, Ardern C, Tamim H (2015) Predictors of adherence in acommunity-based Tai Chi program. Can J Aging 34(2): 237-246.

- Yang GY, Wang LQ, Ren J, Zhang Y, Li ML, et al. (2015) Evidence baseof clinical studies on Tai Chi: a bibliometric analysis. PLoS One 10(3):e0120655.

- SBao X, Jin K (2015) The beneficial effect of Tai Chi on self-concept inadolescents. Int J Psychol. 50(2): 101-115.

- Zheng G, Lan X, Li M, Ling K, Lin H, Chen L, et al. (2015) Effectivenessof Tai Chi on physical and psychological health of college students:Results of a Randomized controlled trial. PLoS One 10(7): e0132605.

- Webster CS, Luo AY, Krageloh C, Moir F, Henning M (2015) A systematicreview of the health benefits of Tai Chi for students in higher education.Prev Med Rep 3: 103-112.

- Zacharia S, Taylor EL, Hofford CW, Brittain DR, Branscum PW (2015)The effect of an 8-week Tai Chi exercise program on physical functionalperformance in middle-aged women. J Appl Gerontol 34(5): 573-589.

- Sun J, Kanagawa K, Sasaki J, Ooki S, Xu H, et al. (2015) Tai Chi improvescognitive and physical function in the elderly: a randomized controlledtrial. J Phys Sci 27(5): 1467-1471.

- Lu X, Siu KC, Fu SN, Hui-Chan CW, Tsang WW (2016) Effects of Tai Chitraining on postural control and cognitive performance while dualtasking- a randomized clinical trial. J complement Integr Med [Epubahead of print].

- Fong DY, Chi LK, Li F, Chang YK (2014) The benefits of enduranceexercise and Tai Chi Chuan for the task-switching aspect of executivefunction in older adults: an ERP study. Front Aging Neurosci 6: 295.

- Hawkes TD, Manselle W, Woollacott MH (2014) Tai Chi and meditationplus-exercise benefit neural substrates of executive function: a crosssectional,controlled study. J Complement Integr Med 11(4): 279- 288.

- Toa J, Liu J, Egorova N, Chen X, Sun S, et al. (2016) Increasedhippocampus-medical prefrontal cortex resting-state functionalconnectivity and memory function after Tai Chi Chuan practice in elderadults. Front Aging Neurosci 8: 25.

- Walsh JN, Manor B, Hausdorff J, Novak V, Lipsitz L, et al. Impact ofshort-and long-term Tai Chi mind-body exercise training on cognitivefunction in healthy adults: results from a hybrid observational studyand randomized trial. 2015(4): 38-48.

- Zheng G, Liu F, Li S, Huang M, Tao J, et al. (2015) Tai Chi and theprotection of cognitive ability: a systematic review of prospectivestudies in healthy adults. Am J Prev Med 49(1): 89-97.

- Wayne PM, Walsh JN, Taylor-Piliae RE, Wells RE, Papp KV, et al. Effectof Tai Chi on cognitive performance in older adults: systematic reviewand meta-analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc 62(1): 25-39.

- Lee LY, Tam KW, Lee ML, Lau NY, Lau JC, et al. (2015) Sleep quality ofmiddle-aged Tai Chi practioners. Jpn J Nurs Sci 12: 27-34.

- Irwin MR, Olmstead R, Carrillo C, Sadeghi N, Breen EC, et al. (2014)Cognitive behavioral therapy vs. Tai Chi for late life insomnia andinflammatory risk: a randomized controlled comparative efficacy trial.Sleep 37(9): 1543-1552.

- Sharma M, Haider T (2015) Tai Chi as an alternative and complementarytherapy for anxiety: a systematic review. J Evid Based ComplementAltern Med 20(2):143-153.

- Li Y, Su Q, Guo H, Wu H, Du H, et al. (2014) Long-term Tai Chi trainingis related to depressive symptoms among Tai Chi practitioners. J AffectDisord 169: 36-39.

- Chi I, Jordan Marsh M, Guo M, Xie B, Bai Z (2013) Tai Chi and reduction ofdepressive symptoms for older adults: a meta-analysis of randomizedtrials. Geriatr Gerontol Int 13(1): 3-12.

- Wang F, Lee Ek, Wu T, Benson H, Fricchione G, et al. (2014) The effectsof Tai Chi on depression, anxiety, and psychological well-being: asystematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Behav Med 21(4): 605-617.

- Liu X, Vitetta L, Kostner K, Crompton D, Williams G, et al. (2015) Theeffects of Tai Chi in centrally obese adults with depression symptoms.Evid Based Complement Alternat Med.

- Maris SA, Quintanilla D, Taetzsch A, Picard A, Letendre J, et al. (2014)The combined effects of Tai Chi, resistance training, and diet on physicalfunction and body composition in obese older women. J Aging Res.

- Hsu WH, Hsu RW, Lin ZR, Fan CH (2015) Effects of circuit exercise andTai Chi on body composition in middle-aged and older women. GeriatrGerontol Int 15(3): 282-288.

- Ho RT, Fong TC, Wan AH, Au-Yeung FS, Wong Cp, et al. (2016) Arandomized controlled trial on the psychophysiological effects ofphysical exercise and Tai-Chi in patients with chronic schizophrenia.Schizophr Res 171(1-3): 42-49.

- Xu F, Letendre J, Bekke J, Beebe N, Mahler L, et al. (2015) Impact ofa program of Tai Chi plus behaviorally based dietary weight losson physical functioning and coronary heart disease risk factors: acommunity-based study in obese older women. J Nutr Gerontol Geriatr34(1): 50-65.

- Hartley L, Flowers N, Lee MS, Ernst E, Rees K (2014) Tai Chi for primaryprevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (4):CD010366.

- Robins JL, Elswick RK Jr, Sturgill J, McCain NL (2016) The effects of TaiChi on cardiovascular risk in women. Am J Health Promot 30(8): 613-622.

- Sun J, Buys N (2015) Community-based mind-body meditative Tai Chiprogram and its effects on improvement of blood pressure, weight,renal function, serum lipoprotein and quality of life in Chinese adultswith hypertension. Am J Cardiol 116(7):1076-1081.

- Pan X, Zhang Y, Tao S (2015) Effects of Tai Chi exercise on bloodpressure and plasma levels of nitric oxide, carbon monoxide andhydrogen sulfide in real-world patients with essential hypertension.Clin Exp Hypertens 37: 8-14.

- Shi ZM, Wen HP, Liu FR, Yao CX (2014) The effects of Tai Chi on therenal and cardiac functions of patients with chronic kidney andcardiovascular diseases. J Phys Ther Sci 26(11): 1733-1736.

- Nery RM, Zanini M, de Lima JB, Buhler RP, da Silveira AD, et al. (2015)Tai Chi Chuan improves functional capacity after myocardial infarction:a randomized clinical trial. Am Heart J 169(6): 854- 860.

- Nery RM, Zanini M, Ferrari JN, Silva CA, Farias LF, et al. (2014) Tai ChiChuan for cardiac rehabilitation in patients with coronary arterialdisease. Arq Bras Cardiol 102(6): 588-592.

- Taylor-Piliae RE, Hoke Tm, Hepworth JT, Latt LD, Najafi B, et al. (2014)Effect of Tai Chi on physical function, fall rates and quality of life amongolder stroke survivors. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 95(5): 816-824.

- Zheng G, Huang M, Liu F, Li S, Chen L (2015) Tai Chi Chuan for theprimary prevention of stroke in middle-aged and elderly adults:a systematic review. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2015:742152.

- Song QH, Xu RM, Shen GQ, Zhang QH, Ma M, et al. (2014) Influenceof Tai Chi exercise cycle on the senile respiratory and cardiovascularcirculatory function. Int J Clin Exp Med 7(3): 770-774.

- Holmes ML, Manor B, Hsieh WH, Hu K, Lipsitz LA, et al. (2016) Tai Chitraining reduced coupling between respiration and postural control.Neurosci Lett 610: 60-65.

- Zheng G, Li S, Huang M, Liu F, Tao J, et al. (2015) The effect of Tai Chion cardiorespiratory fitness in healthy adults: a systematic review andmeta-analysis. PloS One 10(2): e0117360.

- Qiu ZH, Guo HX, Lu G, Zhang N, He BT, et al. (2016) Physiologicalresponses to Tai Chi in stable patients with COPD. Respir PhysiolNeurobiol 221: 30-34.

- Niu R, He R, Luo BL, Hu C (2014) The effect of Tai Chi on chronicobstructive pulmonary disease: a pilot randomized study of lung function, exercise capacity and diaphragm strength. Heart Lung Circ23(4): 347-352.

- Guo JB, Chen BL, Lu YM, Zhang WY, Zhu ZJ, et al. (2015) Tai Chi forimproving cardiopulmonary function and quality of life in patientswith chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review andmeta-analysis. Clin Rehabil 30(8): 750-764.

- Wu W, Liu X, Wang L, Wang Z, Hu J, et al. (2014) Effects of Tai Chi onexercise capacity and health-related quality of life in patients withchronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review and metaanalysis.Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 9: 1253-1263.

- Li G, Yuan H, Zhang W (2014) Effects of Tai Chi on health related qualityof life in patients with chronic conditions: a systematic review ofrandomized controlled trials. Complement Ther Med 22(4): 743-755.

- Cho Y (2014) Effects of Tai Chi on pain and muscle activity in youngmales with acute low back pain. J Phys Ther Sci 26(5): 679-681.

- Callahan LF, Cleveland RJ, Altpeter M, Hackney B (2016) Evaluationof Tai Chi program effectiveness for people with arthritis in thecommunity: a randomized controlled trial. J Aging Phys Act 24(1): 101-110.

- Ye J, Cai S, Zhong W, Cai S, Zheng Q (2014) Effects of Tai Chi for patientswith knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review. J Phys Ther Sci 26: 1133-1137.

- Zeng R, Lin J, Wu S, Chen S, Gao H, et al. (2015) A randomized controlledtrial: preoperative home-based combined Tai Chi and strength training(TCST) to improve balance and aerobic capacity in patients with totalhip arthroplasty (THA). Arch Gerontol Geriatr 60(2): 265-271.

- Shin JH, Lee Y, Kim SG, Choi BY, Lee HS, et al. (2015) The beneficialeffects of Tai Chi exercise on endothelial function and arterial stiffnessin elderly women with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther 17: 380.

- Geib RW, Li H, Waite GN (2014) A pilot study on the effect of Tai Chiexercise on peripheral cytokines associated with nociceptive pain inhealthy volunteers. Biomed Sci Instrum 50: 125-131.

- Segura-Jimenez V, Romero-Zurita A, Carbonell-Baeza A, Aparicio VA,Ruiz JR, et al. Effectiveness of Tai Chi for decreasing acute pain infibromyalgia patients. Int J Sports Med 35(5): 418-423.

- Shem K, Karasik D, Carufel P, Kao MC, Zheng P (2016) Seated Tai Chito Alleviate and improve quality of life in individuals with spinal corddisorder. J Spinal Cord Med 39(3): 353-358.

- Tsang WW, Gao KL, Chan KM, Purves S, Macfarlane DJ, et al. (2015)Sitting Tai Chi improves the balance control and muscle strength ofcommunity-dwelling persons with spinal cord injuries: a pilot study.Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2015: 523852.

- Hui SS, Xie YJ, Woo J, Kwok TC (2015) Effects of Tai Chi and walkingexercises on weight loss, metabolic syndrome parameters, and bonemineral density: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Evid. BasedComplement Alternat Med 2015: 976123.

- Lee MS, Jun JH, Lim HJ, Lim HS (2015) A systematic review and metaanalysisof Tai Chi for treating type 2 diabetes. Maturitas 80(1): 14-23.

- Burschka JM, Keune PM, Oy UH, Oschmann P, Kuhn P (2014)Mindfulness-based interventions in multiple sclerosis: beneficialeffects of Tai Chi on balance, coordination, fatigue and depression. BMCNeurol 14: 165.

- Azimzadeh E, Hosseini MA, Nourozi K, Davidson PM (2015) Effect of TaiChi Chuan on balance in women with multiple sclerosis. ComplementTher Clin Pract 21(1): 57-60.

- Huang XY, Eungpinichpong W, Silsirivanit A, Nakmareong S, Wu XH(2014) Tai Chi improves oxidative stress response and DNA damage/repair in young sedentary females. J Phys Ther Sci 26(6): 825-829.

- Mendoza-Nunez VM, Hernandez-Monjaraz B, Santiago-Osorio E,Betancourt-Rule JM, Ruiz-Ramos M (2014) Tai Chi exercise increasesSOD activity and total antioxidant status in saliva and is linked to animprovement of periodontal disease in the elderly. Oxid Med CellLongev 2014: 603853.

- Irwin MR, Olmstead R, Breen EC, Witarama T, Carrillo C, et al. (2015)Cognitive behavioral therapy and Tai Chi reverse cellular and genomicmarkers of inflammation in late-life insomnia: a randomized controlledtrial. Biol Psychiatry 78(10): 721-729.

- Irwin MR, Olmstead R, Breen EC, Witarama T, Carrillo C, et al. (2014)Tai Chi cellular inflammation, and transcriptome dynamics in breastcancer survivors with insomnia: a randomized controlled trial. J NatlCancer Inst Monogr 2014(50): 295-301.

- Pan Y, Yang K, Shi X, Liang H, Zhang F, et al. (2015) Tai Chi Chuanexercise for patients with breast cancer: a systematic review and metaanalysis.Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2015: 535237.

- Zhang LL, Wang SZ, Chen HL, Yuan AZ (2016) Tai chi exercise for cancerrelatedfatigue in patients with lung cancer undergoing chemotherapy:a randomized controlled trial. J Pain Symptom Manage 51(3): 504-511.

- Lui J, Chen P, Wang R, Yuan Y, Wang X, Li C (2015) Effect of Tai Chi onmononuclear cell functions in patients with non-small cell lung cancer.BMC Complement Altern Med 15: 3.

- Campo RA, Light KC, O’Connor K, Nakamura Y, Lipschitz D, et al. (2015)Blood pressure, salivary cortisol, and inflammatory cytokine outcomesin senior female cancer survivors enrolled in a Tai Chi Chih randomizedcontrolled trial. J Cancer Surviv 9(1): 115-125.

- Zeng Y, Luo T, Xie H, Huang M, Cheng AS (2014) Health benefits ofqigong or Tai Chi for cancer patients: a systematic review and metaanalysis.Complement Ther Med 22(1): 173-186.

- Ho TJ, Ho LI, Hsueh KW, Chan TM, Huang SL, et al. (2014) Tai Chiintervention increases progenitor CD34(+) cells in young adults. CellTransplant 23(4-5): 613-620.

- Song QH, Shen GQ, Xu RM, Zhang QH, Ma M, et al. (2014) Effect of TaiChi exercise on the physical and mental health of the elder patientssuffered from anxiety disorder. Int J Physiol Pathophysiol Pharmacol6(1): 55-60.

- Liu Yw, Tsui CM (2014) A randomized trial comparing Tai Chi withand without cognitive-behavioral intervention (CBI) to reduce fear offalling in community-dwelling elderly people. Arch Gerontol Geriatr59(2): 317-325.

- Hwang HF, Chen SJ, Lee-Hsieh J, Chien DK, Chen CY, et al. (2016) Effectsof home-based Tai-Chi and lower extremity training and self-practiceon falls and functional outcomes in older fallers from the emergencydepartment- a randomized controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc 64(3):518-525.

- Varghese R, Hui-Chan CW, Bhatt T (2015) Reduced Cognitive-motorinterference on voluntary balance control in older Tai Chi practioners.J Geriatr Phys Ther 39(4): 190-199.

- Wayne PM, Hausdorff JM, Lough M, Gow BJ, Lipsitz L, et al. (2015) TaiChi training may reduce dual task gait variability, a potential mediatorof fall risk, in healthy older adults: cross-sectional and randomized trialstudies. Front Hum Neurosci 9: 332.

- Zhou J, Chang S, Cong Y, Qin M, Sun W, et al. (2015) Effects of 24 weeksof Tai Chi Exercise on Postural Control among Elderly Women. ResSports Med 23(3): 302-314.

- Guo LY, Yang CP, You YL, Chen SK, Yang CH, et al. (2014) Underlyingmechanisms of Tai-Chi-Chuan training for improving balance ability inthe elders. Chin J Integr Med 20(6): 409-415.

- Rahal MA, Alonso AC, Andrusaitis FR, Rodrigues TS, Speciali DS, etal. (2015) Analysis of static and dynamic balance in healthy elderlypractitioners of Tai Chi Chuan versus ballroom dancing. Clinics (SaoPaulo) 70(3): 157-161.

- Yildirim P, Ofluoglu D, Aydogan S, Akyuz G (2016) Tai Chi vs. combinedexercise prescription: a comparison of their effects on factors related tofalls. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil 29(3): 493-501.

- Ni M, Mooney K, Richards L, Balachandran A, Sun M, et al. (2014)Comparative impacts of Tai Chi, balance training, and a speciallydesignedyoga program on balance in older fallers. Arch Phys MedRehabil 95(9): 1620-1628.