The Mediterranean Diet as First Medicine

Giacinto Bagetta, Rossella Russo*, Annagrazia Adornetto and Luigi Antonio Morrone

Department of Pharmacy, University of Calabria, Italy

Submission: June 13, 2016; Published: July 15, 2016

*Corresponding author: Rossella Russo, Department of Pharmacy Health Science and Nutrition, Via Pietro Bucci, 87036 Rende (Cosenza) Italy, Tel: +39 0984 493462; Fax:+390984493462; Email:g.bagetta@unical.it

How to cite this article: Giacinto B, Rossella R, Annagrazia A, Luigi AM. The Mediterranean Diet as First Medicine. J Anest & Inten Care Med. 2016; 1(2) : 555558. DOI: 10.19080/JAICM.2016.01.555558

Abstract

The traditional Mediterranean diet, highly rich in fruits and vegetables and limited in saturated fatty acids, has been associated with reduced incidence of cardiovascular, degenerative and cancer diseases and a long life expectancy. Here we review recent acquisitions showing that the adherence to Mediterranean diet have positive impact on age-related cognitive decline and therefore it can improve the quality of life in patients suffering of Alzheimer’s and other types of dementia.

Introduction

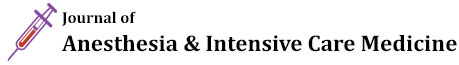

It is widely known that Italian and Japanese are among the most long living people. This notion is in agreement with the recent epidemiological data published in May 2015 [1]. by the World Health Organization (WHO); accordingly, a child born now in Italy has a life expectancy only one year shorter than that of a child born in any island of Japan (83 and 84 years, respectively; (Figure 1). This condition can be attributed, at least in part, to the high quality of the health systems of both countries, a deduction supported by epidemiological data demonstrating similar mortality risk in both countries among the population between 15 and 60 years of age (WHO 2015).

Other than good health systems, these two countries share the cultural value of their diet and the consumption of traditional food and this has been always considered important for excellent physical and mental health preservation and to warrant longevity.

Based on apparently diverse, though tasty, food (i.e. pasta vs rice, olive olives soy, mozzarella cheeses tofu, wine vs sake, basil vsshiso), these two diets share their prevailing, but not exclusive, vegetal nature; Infact, fish and meet are also consumed, the former but not the latter eaten mostly raw in Japan, the reverse being true for Italy.

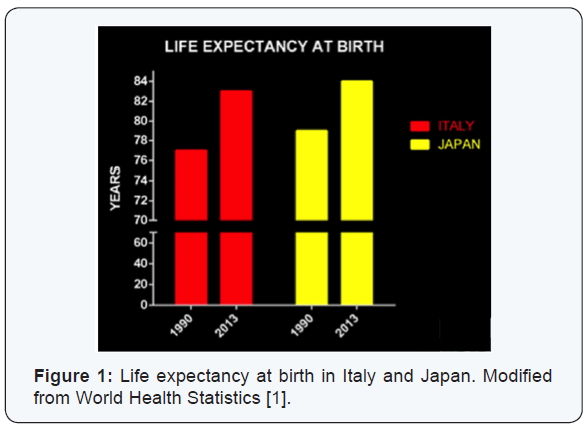

The vegetal pattern (highly rich in fruits and vegetables) in conjunction with the low content in saturated fatty acids (8% in energy value) of the Mediterranean diet, as described also in its quantities by the recent revision of the alimentary pyramid (Figure 2), is considered the basis for reduced incidence of some degenerative and cancer diseases and long life expectancy; its positive health impact has been known since the sixties when it was first monitored among the populations of Crete, other areas of Greece and southern Italy [2] thus granting to the Mediterranean diet the value of “first medicine”.

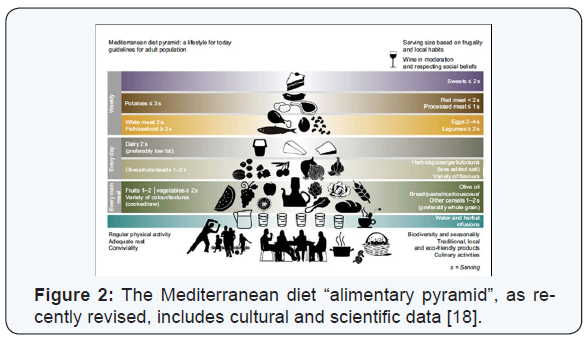

The mechanism underlying the positive health impact of the Mediterranean diet has been the object of intense basic and clinical researches; these have previously defined the chemical food composition and, more recently, have identified the biologically active ingredients in conjunction with their health properties (Table 1).

The wide variety (also chromatic) of fruits and other vegetables (vegetables, herbs, cereals, etc) makes the Mediterranean diet particularly rich in principles generally defined as anti-oxidants, some of which endowed with important biological activity and health properties preventive of human diseases sometimes serious. Thus, for instance, the constant presence of the extra virgin olive oil (EOO) in the Mediterranean diet plays a fundamental role, among other mechanisms, for increasing the blood level of cholesterol HDL and reducing the LDL, minimizing the cardiovascular risk, lowering blood pressure, reducing platelet aggregation and inflammation, and displaying anti-atherosclerotic activity. Altogether, these actions have been attributed to the content of EOO in monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFA) and to specific anti-oxidants (e.g. tocopherol, hydroxityrosol, oleuropein, etc) able to counteract the detrimental impact of free radicals on the cell [3].

Low to moderate red wine consumption while eating, displays beneficial effects on health, similar to those of EOO, attributed to the content of anti-oxidants (e.g. resveratrol) responsible for reducing the production of endothelin (among the most potent endogenous vasoconstrictors) [4]. Dilating the arterioles and reducing platelet aggregation via nitric oxide production and, hence, reducing the cardiovascular risk. The latter properties of red wine underline the french paradoxupon which the mortality rate for myocardial infarction in France is inversely related to red wine consumption [4-6]. Of unique importance, though of recent acquisition, is the action of specific components of the Mediterranean diet in the modulation of fundamental neurobiological processes.

It is envisaged that adaptive mechanisms that have allowed food acquisition and energy efficiency have operated a great evolutionary pressure on the brain of the modern human being and on the development of its cognitive abilities. Several paleontological evidence suggest a direct relation between food availability and skull dimension and support the notion that even small changes in diet composition may impact negatively on fertility and survival [7]. Greater brains in humanoids have been associated to the development of abilities such as cooking, food acquisition, energy saving, upright walking and running, activities demanding coordination of cognitive functions centered upon food success [7].

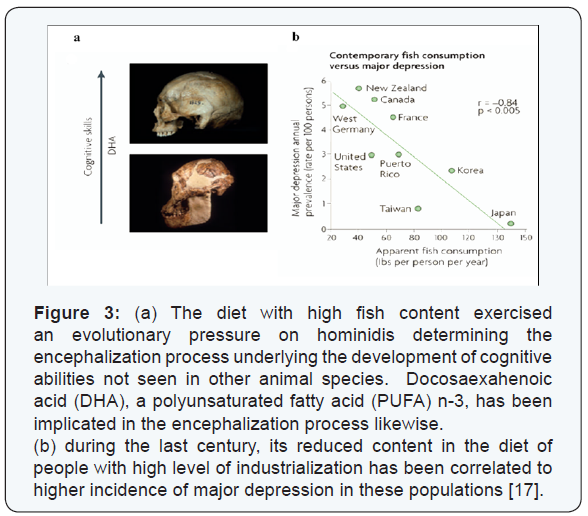

Consumption of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) n-3 is one of the most studied interactions between food and brain evolution. Docosaexahenoic acid (DHA) is one of the most abundant PUFA n-3 in neuronal membrane; mammalians are unable to synthesize DHA and are entirely relianton diet content, mostly present in fish (salmon, bleu fish etc). It has been proposed that access to DHA favored the encephalization process of hominidis (Figure 3a), that is the growth of the brain with respect to the body mass (archeological evidence support the notion that hominids adapted themselves to fish consumption before encephalization; [7].

The relationship between brain and environment is an always active process. During the last century, in highly industrialized societies, increase in saturated fatty acids consumption has been paralleled by reduction in PUFA n-3 (DHA) consumption and this correlates with increased incidence of major depression in countries like USA and Germany (Figure 3b)[7]. In industrialized countries, enhanced survival rate due to socio-economic development is accompanied by a parallel increase of age-related neurodegenerative diseases.

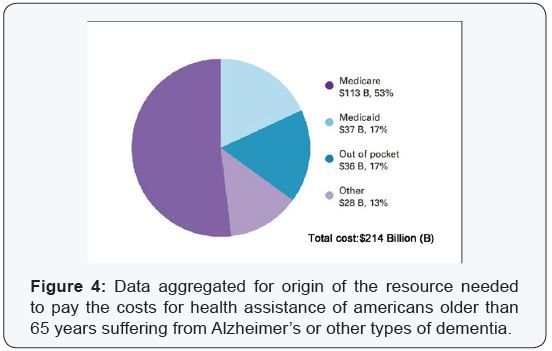

In fact, it is calculated that actually 46.800.000 individuals suffer of dementia worldwide; in Italy the estimated figure is 1.241.000 (50% being of the Alzheimer type) due to increase by 116% in the 2050 [8]. In the USA the cost for care is about 226 billion dollars, and this is paid out for its 30% directly by the pocket of demented patients (Figure 4).

The neuron is highly vulnerable to the detrimental effects of oxidative stress and antioxidants slow the aging process and neuronal degeneration [9], this stimulated, during the last two decades, a wealth of scientific researches with disappointing results. In fact, clinical trials have failed to demonstrate measurable efficacy over placebo of individual active principles (e.g. antioxidants like Vit. E) in slowing down the cognitive decline and the degenerative process in Alzheimer’s patients [10].

Nonetheless, these negative data do not undermine the important role played by oxidative stress in age-related neurodegenerative processes. Therefore, it is conceivable that long term exposure through the diet to food endowed with high content of antioxidants may slow down degenerative cellular processes linked to aging. This hypothesis, in conjunction with the notion that the Mediterranean diet is based on foods endowed with high amount of antioxidants, has formed the rational for several clinical trials that have yielded inconclusive results on the validity of the Mediterranean diet. It is conceivable that the inconclusive nature of most of the trials of the past stems from the poor trial design and from the lack of markers with which to monitor the diet adherence.

Accordingly, in a cohort of aged subjects selected and monitored rigorously recent experimental evidence shows that adherence to the Mediterranean diet allows measurable results to be achieved on cognitive decline. In a recent study published in June 2015 in the prestigious Journal of the American Medical Association [11] for the first time 447 patients have been randomized and assigned to three arms: 157 have been assigned to Mediterranean diet added with known quantity of EOO, 147 to Mediterranean diet added with known quantity of nuts and 145 assigned to control diet; 127, 112 and 95 individuals, respectively, completed the study. Adherence to the diet has been confirmed by monitoring blood markers. The yielded results demonstrate unequivocally that adherence to the Mediterranean diet for a long period (6 years) impacts positively on memory slowing down significantly the cognitive decline vs control. Furthermore, the trial has shown a positive, specific, effect of EOO on frontal lobe function and on global cognitive function and a specific effect of nuts on different memory forms evaluated using a validated clinical test [11].

Although the latter study does not clarify the mechanisms underlying the effect of the Mediterranean diet on cognitive decline, it is true that the content in antioxidants plays an important role. It is widely demonstrated that DHA prevents den critic spine degeneration in animal models of Alzheimer’s through activation of gene products implicated in neuronal survival and inactivating those involved neuronal death processes [12].

It is well established that drugs for Alzheimer’s disease treatment are of low efficacy, act for a short period of time and are active on cognitive symptoms only [13]. Unfortunately, short after diagnosis, Alzheimer’s patients develop behavioral and psychological symptoms such agitation and aggression, sometimes very serious [14], insensitive to typical Alzheimer’s therapy, not fully effective and un safely treated with antipsychotic drugs(including atypical ones) that, indeed, enhance the risk of death [13]. Accordingly, a warning has been recently launched against the routine use of narcoleptics in Alzheimer’s patients. Concomitantly, it has been demonstrated that treatment of pain (it is calculated some 40-60% sufferers) in Alzheimer’s patients (unable to report it) minimizes serious behavioral and psychological symptoms (agitation, aggression, etc) [15]. Incidentally, it has been reported that DHA reduces experimentally induced chronic pain [16].

The knowledge that the Italian population, likewise the rest of the world, is undergoing a fast progressing aging process (actually, 900.000.000 of individuals over 60 are calculated worldwide with an incremental trend from 22% in 2015 to36% in 2050 vs the general population) accompanied by the dramatic figure of 46.800.000 demented people in the world and 1.241.000 in Italy recalls the huge costs for this age-dependent neurodegenerative disease [14]. In addition, it is mandatory to limit the damage inflicted to patients, caregivers and society by ineffective therapy; indeed, it cannot be postponed any longer the development of a novel strategy of cure built on validated but novel scientific bases in the near future. The latter concept is strengthened by negative results of clinical trials that failed to demonstrate efficacy and safety also, but not exclusively, for biotechnology based therapy of Alzheimer’s disease centered on beta amyloid lowering.

These negative news drive to the huge investments in conjunction with the large attrition in drug research and development encountered recently by industry in this therapeutic area [17].With this in mind, it is envisaged that additional public resources should be invested in research including clinical trials addressing the role of the Mediterranean diet in combating the cognitive decline, minimizing pain symptoms and improving quality of life in Alzheimer’s patients with consequent reduction of major behavioral and psychological disturbances [18,19].

While the researchers will collect more data regarding the mechanisms underlying the health benefits of the Mediterranean diet under physiological and pathological states, hopefully a healthy eating plan, adherent to the Mediterranean dietary pattern, will be designed, adopted and suggested to the patients routinely as part of a good clinical practice.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the Mediterranean diet could reasonably represent at once the right test to prove the maturity of the biomedical and health research system in Italy and to speed up industrial development and market of the Italy trade mark, including environment, agriculture, biodiversity, culture, tradition, etc in great demand in Europe and worldwide.

References

- World Health Statistics (2015) World Health Organization 1-161.

- Hu FB (2003) The mediterranean diet and mortality: olive oil and beyond. New Engl J Med 348(26): 2595-2596.

- Berry EM, Arnoni Y, Aviram M (2014) The Middle Eastern and biblical origins of the Mediterranean diet. Public Health Nutr 14(12A): 2288-2295.

- Corder R, Mullen W, Khan NQ, Marks SC, Wood EG, et al. (2006) Red wine procyanidins and vascular health. Nature 444(7119): 566.

- St. Leger AS, Cochrane AL, Moore F (1979) Factors associated with cardiac mortality in developed countries with particular to the consumption of wine. Lancet 1(8124): 1017-1020.

- Renaud S, de Lorgeril M (1992) Wine, alcohol platelets and the French paradox for coronary heart disease. Lancet 339(8808): 1523-1526.

- Gómez-Pinilla F (2008) Brain foods: the effects of nutrients on brain function. Nat Rev Neurosci 9(7): 568-578.

- Prince M, Wimo A, Guerchet M, Ali G-C, Wu Y-T, et al. (2015) World Alzheimer Report. Edito da Alzheimer Disease International, London.

- Halliwell B (2006) Oxidative stress and neurodegeneration: where are we now? J Neuro chem 97(6): 1634-1658.

- Petersen RC, Thomas RG, Grundman M, Bennett D, Doody R, et al. (2005) Vitamin E and donepezil for the treatment of mild cognitive impairment. Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study Group. N Engl J Med 352(23): 2379-2388.

- Valls-Pedret C, Sala-Vila A, Serra-Mir M, Corella D, de la Torre R, et al. (2015) Mediterranean Diet and Age-Related Cognitive Decline: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med 175(7): 1094-1103.

- Calon F, Lim GP, Yang F, Morihara T, Teter B, et al. (2004) Docosahexaenoic acid protects from dendritic pathology in an Alzheimer’s disease mouse model. Neuron 43(5): 633-645.

- Ballard CG, Gauthier S, Cummings JL, Brodaty H, Grossberg GT, et al. (2009) Management of agitation and aggression associated with Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Neurol 5(5): 245-255.

- Jost BC, Grossberg GT (1996) The evolution of psychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease: a natural history study. J Am Geriatr Soc 44(9): 1078-1081.

- Sandvik RK, Selbaek G, Seifert R, Aarsland D, Ballard C, et al. (2014) Impact of a stepwise protocol for treating pain on pain intensity in nursing home patients with dementia: A cluster randomized trial. Eur J Pain 18(10): 1490-1500.

- Figueroa JD, Cordero K, Serrano-Illan M, Almeyda A, Baldeosingh K, et al. (2013) Metabolomics uncovers dietary omega-3 fatty acid-derived metabolites implicated in anti-nociceptive responses after experimental spinal cord injury. Neuroscience 255: 1-18.

- Amantea D, Certo M, Bagetta G (2015) Drug repurposing and beyond: the fundamental role of pharmacology. Funct Neurol 30(1): 79-81.

- Bach-Faig A, Berry EM, Lairon D, Reguant J, Trichopoulou A, et al. (2011) Mediterranean diet pyramid today. Science and cultural updates. Public Health Nutr 14(12A): 2274-2284.

- Corbett A, Burns A, Ballard C (2014) Don’t use antipsychotics routinely to treat agitation and aggression in people with dementia. Br Med J 349: 1-4.